Abstract

In this paper, we consider the properties of Green’s function for the singular nonlinear fractional differential equation boundary value problem

where is a real number and is the standard Riemann-Liouville differentiation. As an application of the properties of Green’s function, we give the existence of multiple positive solutions for the above mentioned singular boundary value problems. Our tools are Leray-Schauder nonlinear alternative and Krasnoselskii’s fixed-point theorem on cones.

MSC:34A08, 34B18, 45B05.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Fractional differential equations have been of great interest recently. This is due to the intensive development of the theory of fractional calculus itself as well as its applications. Apart from diverse areas of mathematics, fractional differential equations arise in rheology, dynamical processes in selfsimilar and porous structures, fluid flows, electrical networks, viscoelasticity, chemical physics, and many other branches of science. For details, see [1–6]. Now the boundary value problem for fractional differential equations attracts lots of attention. Especially, Jiang and Yuan [7] considered the nonlinear fractional differential equation Dirichlet-type boundary value problem and established the existence of positive solutions for the corresponding BVP. Xu et al. [8] dealt with the following equation:

Some properties of Green’s function for the above BVP were obtained. For other related works on the fractional differential equation, see [9–15].

Motivated by the above mentioned works, we consider the properties of Green’s function for

where is a real number and is the standard Riemann-Liouville differentiation. As an application of Green’s function, we will give the existence of multiple positive solutions for singular boundary value problems (1.1), (1.2). As far as we know, no contributions concerning BVP (1.1), (1.2) exist.

The outline of this paper is as follows. In Section 2, we derive the corresponding Green’s function and some of its properties. In Section 3, by using Leray-Schauder nonlinear alternative and Krasnoselskii’s fixed-point theorem in a cone, we offer criteria for the existence of positive solutions for singular BVP (1.1), (1.2).

2 Background materials and Green’s function

For the convenience of the reader, we present here the necessary definitions from fractional calculus theory. These definitions can be found in the recent literature such as [8].

Definition 2.1 [8]

The Riemann-Liouville fractional integral of order of a function is given by

provided the right-hand side is pointwise defined on .

Definition 2.2 [8]

The Riemann-Liouville fractional derivative of order of a continuous function is given by

where , denotes the integer part of the number α, provided that the right-hand side is pointwise defined on .

From the definition of the Riemann-Liouville derivative, we can obtain the statement.

Lemma 2.1 [8]

Let . If we assume that , then the fractional differential equation

has , , , as unique solutions, where N is the smallest integer greater than or equal to α.

Lemma 2.2 [8]

Assume that with a fractional derivative of order that belongs to . Then

for some , , N is the smallest integer greater than or equal to α.

In the following, we present Green’s function of the fractional differential equation boundary value problem (1.1), (1.2).

Lemma 2.3 Given and , the unique solution of

is

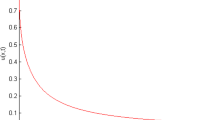

where

Here is called Green’s function of BVP (2.1), (2.2).

Proof We may apply Lemma 2.2 to reduce (2.1) to an equivalent integral equation

for some . Consequently, the general solution of (2.1) is

By (2.2), we get that , and

Therefore, the unique solution of (2.1), (2.2) is

This completes the proof. □

From the expression of , we can obtain the following properties.

Lemma 2.4 Green’s function defined by (2.3) has the following properties:

Proof of (2.4)

where and are used. Thus, (2.4) is verified. □

Proof of (2.5) By direct calculation, we get

On the one hand, for , from (2.4), we can get

On the other hand, for , we have

and

Hence,

In summary, the property (2.5) holds. □

Proof of (2.6) For , we have

and

So, we have

For , we first prove that

For fixed , let

Obviously, and . Equation (2.4) together with

implies that , . Hence (2.7) holds.

By (2.5) we know that is increasing in t on . Hence, for ,

In summary,

This completes the proof of property (2.6). □

As an application of properties of Green’s function, we will establish the existence of positive solutions for BVP (1.1), (1.2) in Section 3, in which Leray-Schauder nonlinear alternative and Krasnoselskii’s fixed-point theorem on cones are our main tools. For the convenience of the reader, we recall the two famous theorems here.

Lemma 2.5 Assume that Ω is a relative subset of a convex set K in a normed space X. Let be a compact map with . Then

-

(a)

A has a fixed point in , or

-

(b)

there are and such that .

Lemma 2.6 Let E be a Banach space, and let be a cone in E. Assume that , are open subsets of E with , and let be a completely continuous operator such that either

-

(i)

, ; , ; or

-

(ii)

, ; , .

Then T has a fixed point in .

3 Positive solution of a singular problem

In this section, we establish the existence of positive solutions for singular BVP (1.1), (1.2). Throughout this section, we always assume that is continuous. Given , we write if for and it is positive in a subset of positive measure.

Let be endowed with the maximum norm, .

Theorem 3.1 Suppose that the following hypotheses hold:

(H1) for each constant , there exists a continuous function such that for all ;

(H2) there exist continuous, nonnegative functions and such that

where is nonincreasing and is nondecreasing in ;

(H3) there exists a constant such that for all ;

(H4) ;

(H5) there exists a positive number r such that

Then BVP (1.1), (1.2) has at least one positive solution u with .

Proof Choose such that . For fixed , consider the family of integral equations

where , and , . We claim that any solution of (3.1) for any must satisfy . Otherwise, assume that is a solution of (3.1) for some such that . Note that by (2.6),

Hence, for all , by (2.6) again, we have

Thus, it follows from the choice of , (3.2), (2.6), (H2) and (H3) that for all ,

Therefore,

which contradicts (H5) and the claim is proved.

It is easy to check from (2.5), (2.6) and (H4) that the operator

is completely continuous, where . We omit the details here.

Now Lemma 2.5 guarantees that the integral equation has a solution, denoted by , in .

From (H1), we know that there exists a function such that for all ,

where .

By using (2.5), (3.5) and a similar calculation as in (3.3), we have that for all ,

and

The Arzela-Ascoli theorem guarantees that has a subsequence converging uniformly on to a function . By the Lebesgue dominated convergence theorem, we have that

where (3.5) is used. Therefore, is a positive solution of BVP (1.1), (1.2). □

Theorem 3.2 Suppose that (H2), (H3), (H4) and (H5) are satisfied. Furthermore, assume that (H6) there exists a positive number such that the following inequality holds:

Then BVP (1.1), (1.2) has another solution with .

Proof To show the existence of , we will use Lemma 2.6. Define

It is obvious that K is a cone on . Let

Next, the operator is defined by

It is easy to check that the operator T maps into K. In fact, for any , we have from (2.6) that for ,

and

This implies that , that is, . In addition, by a similar argument as in Theorem 3.1, it is not difficult to prove that the operator is completely continuous. Now we prove that

For any , from (2.6), (H2), (H3), (3.6) and (H5), we have that for ,

Therefore, (3.7) holds. Next, we will prove that

For any , from (2.6), (H2), (H3), (3.6) and (H6), we have that

This implies that (3.8) holds.

It follows from Lemma 2.6 that the operator T has a fixed point . Clearly, this fixed point is a positive solution of BVP (1.1), (1.2) satisfying . □

Example 3.1 Consider the boundary value problem

where , and is a given parameter.

Corollary 3.1 Assume that , .

-

(i)

If , then (3.9) has at least one nonnegative solution for each .

-

(ii)

If , then (3.9) has at least one nonnegative solution for each , where is some positive constant.

-

(iii)

If , then (3.9) has at least two nonnegative solutions for each .

Proof We will apply Theorems 3.1 and 3.2 to obtain our desired results. Note that (H1) holds with . Let

Then (H2) and (H3) are satisfied. Since , (H4) is also satisfied. Now for (H5) to be satisfied, we need

for some , where

Therefore, (3.9) has at least one nonnegative solution for

Note that if , . If , set

The function possesses a maximum at

then . We have the desired results (i) and (ii). If , condition (H6) becomes

for some , where

Since , the right-hand side of (3.10) tends to 0 as . Thus, for any given , it is always possible to find an such that (3.10) is satisfied. Therefore, (3.9) has another nonnegative solution . This implies that (iii) holds. □

References

Kilbas AA, Srivastava HM, Trujillo JJ North-Holland Mathematics Studies 204. In Theory and Applications of Fractional Differential Equations. Elsevier, Amsterdam; 2006.

Oldham KB, Spanier J: The Fractional Calculus. Academic Press, New York; 1974.

Nonnenmacher TF, Metzler R: On the Riemann-Liouville fractional calculus and some recent applications. Fractals 1995, 3: 557-566. 10.1142/S0218348X95000497

Tatom FB: The relationship between fractional calculus and fractals. Fractals 1995, 3: 217-229. 10.1142/S0218348X95000175

Podlubny I Mathematics in Science and Engineering 198. In Fractional Differential Equations. Academic Press, New York; 1999.

Samko SG, Kilbas AA, Marichev OI: Fractional Integral and Derivatives: Theory and Applications. Gordon & Breach, Yverdon; 1993.

Jiang D, Yuan C: The positive properties of the Green function for Dirichlet-type boundary value problems of nonlinear fractional differential equations and its application. Nonlinear Anal. 2010, 72: 710-719. 10.1016/j.na.2009.07.012

Xu X, Jiang D, Yuan C: Multiple positive solutions for the boundary value problem of a nonlinear fractional differential equation. Nonlinear Anal. 2009, 71: 4676-4688. 10.1016/j.na.2009.03.030

Babakhani A, Gejji VD: Existence of positive solutions of nonlinear fractional differential equations. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2003, 278: 434-442. 10.1016/S0022-247X(02)00716-3

Delbosco D, Rodino L: Existence and uniqueness for a nonlinear fractional differential equation. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1996, 204: 609-625. 10.1006/jmaa.1996.0456

Zhang S: The existence of a positive solution for a nonlinear fractional differential equation. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2000, 252: 804-812. 10.1006/jmaa.2000.7123

Zhang S: Existence of positive solution for some class of nonlinear fractional differential equations. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2003, 278: 136-148. 10.1016/S0022-247X(02)00583-8

Nakhushev AM: The Sturm-Liouville problem for a second order ordinary differential equation with fractional derivatives in the lower terms. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 1977, 234: 308-311.

Bai Z, Lü H: Positive solutions for boundary value problem of nonlinear fractional differential equation. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2005, 311: 495-505. 10.1016/j.jmaa.2005.02.052

Benchohra M, Graef JR, Hamani S: Existence results for boundary value problems with nonlinear fractional differential equations. Appl. Anal. 2008, 87(7):851-863. 10.1080/00036810802307579

Acknowledgements

The author Yuguo Lin would like to express his gratitude to Professor Daqing Jiang for his careful direction. This work was partially supported by NSFC of China (No. 11201008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed equally in this article. They read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Jin, M., Lin, Y. Positive properties of Green’s function for focal-type BVPs of singular nonlinear fractional differential equations and its application. Adv Differ Equ 2013, 159 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-1847-2013-159

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-1847-2013-159