Abstract

Background

Rapid changes in lifestyle have led to a global obesity epidemic. Understanding the economic burden associated with the obesity epidemic is essential to decision making of cost-effective interventions. This study reviewed costs of obesity and intervention programs in Canada, assessed the scope and quality of existing cost analyses, and identified implications for economic evaluations and public health decision makers.

Methods

A systematic search of costs associated with obesity or intervention program in Canada between 1990 and 2011 yielded 10 English language articles eligible for review.

Results

The majority of studies was prevalence-based or top-down costing; 40% had excellent quality assessed using the Quality of Health Economic Study scale. The aggregated annual costs of obesity in Canada ranged from 1.27 to 11.08 billion dollars. Direct costs accounted for 37.2% to 54.5% of total annual costs. Between 2.2% and 12.0% of Canada's total health expenditures were attributable to obesity. The average annual physician cost of overweight male ($ 427) and female ($ 578) adults was lower than that of obese male ($ 475) and female ($ 682) adults; this cost differential across weight status groups was comparable to that found in adolescents. The cost for implementation and maintenance of a school-based obesity prevention program was $ 23 per student.

Conclusions

We observed high costs associated with overweight and obesity and modest costs for obesity prevention programs; however, no cost-effectiveness study of obesity interventions has been performed in Canada. Cost-effectiveness analyses of preventive programs that constitute incidence-based life-time modeling of costs and health outcomes from societal perspective are urgently needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Review

Background

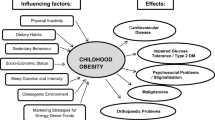

Obesity has rapidly developed into a major global public health challenge. In Canada, 24% of adults are obese and the rates of childhood obesity nearly tripled over the last two decades [1]. Childhood obesity is associated with obstructive sleep apnea, mental health problems, asthma, otitis media, and cardiovascular risk factors [2, 3]. Obesity frequently tracks from childhood into adulthood and increases the risk of developing chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease and some types of cancer [4]. The negative health consequences of obesity place a substantial economic burden on the health care system and society [5].

Economic evidence is indispensable to evaluate the burden of illness and inform health policy development [6]. Obesity is associated with poorer health status, more frequent use of health care services, and increased direct health care costs [7, 8]. Moreover, losses of productivity and healthy life-years due to absenteeism, co-morbidities, disability, and premature mortality are substantial indirect costs placed on individuals, their families, and society [9]. Evaluating the cost of obesity is essential to facilitate prioritization and resource allocation decisions on obesity prevention programs [10]. In addition, economic evaluations are essential to identify cost-effective and cost-saving obesity interventions towards the sustainability of the public health systems at provincial and federal levels [11, 12].

There has been a growing body of literature on the assessment of economic burden of obesity in various settings [10, 12]. Recent reviews on the topic examined the economic consequences of childhood obesity on health care systems [13], obesity costs in different models of health care systems [5], direct costs of obesity [14], and the cost-effectiveness of obesity interventions [12]. However, differences in health care financing and the heterogeneity in costing approaches hamper comparisons across countries, and call for country-specific reviews. In Canada, specifically, the publicly funded, single-payer health care system facilitates comprehensive access to health care services. There have been several interventions proven effective in controlling childhood and adulthood obesity [15–17]. While scaling up these measures is necessary, decision makers are also interested in economic returns of allocating scare resources on competing health and social problems [6]. To date, little evidence is available about the costs, cost-effectiveness, and cost-savings of these programs in Canadian settings [6]. The present study is a part of a greater effort to develop a framework for economic evaluations of obesity interventions. We aimed to review costs of obesity and intervention programs in Canada, assessed the scope and quality of existing cost analyses, and identified implications for economic evaluations and public health decision makers.

Methods

Literature search and study selection

We searched for journal papers, conference abstracts, and research reports in MEDLINE (via PubMed) and government or organization’s websites in the period from 01 January 1990 to 01 May 2012, regardless of their publication status. We also consulted with experts in the field to identify additional relevant studies or reports. The search terms used for PubMed searches are shown in Table 1. We retrieved the titles and abstracts of these publications for screening. Reference lists of included studies were searched for additional potentially eligible studies. We contacted the authors if there was any annex or supplemental analysis of the papers that were not presented.

Inclusion criteria and selection of studies

All studies that performed any type of cost analysis (including but not limited to cost-of-illness, costs of health care services or prevention programs) related to excess weight in adults or children in Canada were eligible for inclusion in this review.

Two researchers (B.T. and A.O.) independently reviewed the retrieved titles and abstracts. For potentially relevant articles the full-text was obtained and reviewed by both reviewers for possible inclusion in the study. Disagreement between reviewers was solved by discussion. No third party adjudication was necessary.

Data extraction and quality appraisal

Full texts of all selected studies were retrieved and data were extracted using a standardized data extraction form. The form included study details (authors, year, and objectives regarding costs), costing approach (scope, data source, perspective, assumption, and year of cost determination), results (obesity measures, and cost estimates), strengths and limitations, and the quality scoring. For publications that reported similar results of the same work, we selected the most comprehensive paper or report to avoid duplications in the database.

Two researchers (B.T. and A.O.) assessed the quality of selected studies using the Quality of Health Economic Studies (QHES) scale [18]. The QHES consists of 16 criteria in the form of Yes/No questions that were selected by health economics experts. Each question has a weighted point value that creates a band score between 0 and 100. The QHES has been validated and shown to be convergent to other instruments such as the British Medical Journal checklist and the Consensus Health Economic Criteria list [19, 20]. Compared to traditional non-quantitative classifications of studies’ quality, QHES is preferable given its summary score constructed by weighted criteria [18]. The score enables reviewers to directly compare and rank studies according to their quality.

Data analysis

Data are presented as total costs in Canadian Dollar (CDN$) (unless stated otherwise) and stratified by age and sex where available. Quality of studies was rated independently by two reviewers (B.T. and A.O.). Disagreement between reviewers was solved by discussion. No third party adjudication was necessary. Since no threshold for interpreting the QHES exists, we arbitrarily set a score of 90 and above as excellent quality, and a score of 75 to 90 as good quality.

Results

The literature search was performed in May 2012 (search terms: cost, costing, expenditure, economic, financial, obesity, overweight, and Canada). The search yielded 295 articles from PubMed and 15 research reports from other internet sources. Applying the inclusion criteria, 10 studies were selected, including nine cost-of-illness (COI) analyses and one cost analysis of an obesity prevention program.

Scope of cost analyses

Of 10 cost analyses, there were five federal and five provincial estimates (Ontario: n=3; Nova Scotia: n=2). The majority of selected studies examined costs for health care in adults (n=8), while few evaluated the health care costs for adolescents (n=1) and children (n=1). There was only one study that evaluated the costs of an obesity prevention program in children [21].

Based on the data used, two types of COI analyses can be differentiated: prevalence-based analyses and incidence-based analyses. Prevalence-based COI studies determine the direct cost and production losses attributable to all cases in a given year while incidence-based COI studies estimate the present value of the lifetime costs of an illness from onset to conclusion for cases first diagnosed within the study year. The majority of selected studies (n=8) were prevalence-based COI studies; only one study was an incidence-based COI analysis [7].

All studies used a top-down approach which multiplied health care unit costs by size of population. Five studies estimated costs at the population level, while the four other studies analyzed data of individuals. The scope of all five population estimates included direct health care costs, and four of them, except Bimingham et al., also estimated indirect costs, such as losses in productivity from a societal perspective (Table 2). Of the four individual analyses, the scope was more focused on direct medical service costs and health care utilization of overweight and obese individuals from the perspective of a provincial health care system (n=2) or the third party payer (n=2). The studies determined physician costs (n=4), and health services costs (e.g. costs of hospital stays or laboratory tests) (n=2). Details of cost components included in these analyses are shown in Table 2.

Six of the studies described the thresholds for classifying weight status: five used BMI cut-offs of ≥25 kg/m2 and ≥30 kg/m2 for overweight and obesity, respectively, while one study used an obesity threshold of BMI ≥27 kg/m2 [22].

Quality of the evidence

The QHES scores ranged from 77 to 97 (Table 3). The proportion of studies of good or excellent quality was 40% and 60%, respectively. A higher average score was seen in health services cost analyses (mean ± SD = 88.8 ± 6.2) compared to COI studies (86.0 ± 7.1). Table 4 illustrates a breakdown of QHES responses by question. The majority of studies met quality criteria defined by the QHES; 13/16 criteria were positively rated in more than 90% studies. The low positive response rate was seen in the following questions: Question 5 (50%), “Was uncertainty handled by (1) statistical analysis to address random events, (2) sensitivity analysis to cover a range of assumptions?”; Question 6 (10%), “Was incremental analysis performed between alternatives for resources and costs?”; Question 16 (70%), “Was there a statement disclosing the source of funding for the study?”. The corresponding scores of question 5, 6, and 16 in the total QHES score was 9, 6, and 3, respectively.

Costs analyses of obesity and obesity prevention programs

Table 5 summarizes the economic burden of overweight and obesity in the Canadian settings. The aggregated annual costs of obesity in Canada ranged from 1.27 to 11.08 billion dollars. In those studies that presented both direct and indirect costs, the total direct costs accounted for 37.2% to 54.5% of total annual costs. In most studies, direct and indirect costs accounted for approximately 2 to 4% of the total health care expenditure. Noticeably, Patra et al. estimated the total costs of obesity ranged from 2.4% to 12% of total health care expenditure in Canada in 1997 [23].

In health service costs analyses, the average annual physician cost of overweight male ($ 427) and female ($ 578) adults was lower than that of obese male ($ 475) and female ($ 682) adults in 2000; this cost differential across weight status groups was comparable to that found in adolescents [8]. Costs for physician services were estimated to increase by $ 9 for each unit increase in BMI in 1994 [24]. Tarride et al. estimated the physician, hospitalization and day procedures costs of normal weight, underweight, overweight, and obese adults in 2000 to be $ 708, $ 746, $ 690 and $ 884. Kuhle et al. reported the 2006 physician costs of normal weight, overweight, and obese children to be $ 275, $ 298, and $ 356, respectively [7].

In the only cost analysis of a school-based obesity prevention program in Canada, Ohinmaa et al estimated the costs for the school board-wide implementation and maintenance of the program at $ 344,514, or $ 7,830 per school and $ 23 per student [21].

Relative Risks (RR) and Population Attributable Fractions (PARF) of Obesity-related diseases

Estimates of relative risks and population attributable fractions of health conditions associated with overweight and obesity are key components of COI studies. The number of obesity-related health conditions ranged from 8 to 22 in the five COI studies. RRs and PARFs of 18 related-health conditions compiled by Anis et al. were the most comprehensive estimates among those accessible detailed analyses [11].

Discussion

We reviewed studies that evaluated the costs of overweight and obesity and costs of prevention programs to inform the design of economic evaluations of obesity interventions in Canada. The findings indicate that the economic burden of obesity is substantial and requires swift and comprehensive public health action. The fraction of total health care costs attributable to overweight and obesity in Canada was estimated to be as high as 12%. By contrast, there is scarce data on the costs of obesity prevention interventions in Canada to inform economic evaluations and to aid resource allocation decisions. The included cost analysis of a comprehensive school health program in Nova Scotia showed that this intervention was not resource-intensive compared to the costs of programs in other countries: For example, Carter et al. estimated the costs of various school-based obesity prevention programs in Australia to be in the range of AUS$ 28 to AUS$ 473 per student. It is important to stress that the cost of obesity treatment is considerably higher than the prevention costs. The former was estimated to be between AUS $ 650 to AUS $ 31,553 depending on the type of therapy [25]. A recent review by John et al. found heterogeneity in cost-effectiveness analyses and study quality of obesity interventions, which hampers comparison of data from different settings [10, 12]. Therefore, costing should be integrated at the implementation of prevention projects and the resulting data should be made accessible for cost-effectiveness analyses.

We assessed the quality of cost analyses using the QHES and found a lack of uncertainty handling and incremental analyses as the main shortcomings of the reviewed studies. In addition, most studies did not clearly present the unit costs of obesity-related chronic conditions that limits the comparison across settings.The approach used in estimating the economic burden of obesity based on the population-attributable risks of co-morbidities is similar to previous works but the method has some drawbacks. The included COI analyses assumed that co-morbidities were mutually exclusive, and their relative risks were estimated mostly from data outside Canada.

This review identified several implications for future research. First, more bottom-up COI analyses and program costs analyses in Canadian settings are needed to guide economic evaluation of and resource allocation for obesity prevention programs. Costs analyses should include more detailed stratifications, (e.g., by sex and age), and uncertainty analysis should be used. Second, a systematic synthesis and estimate of parameters, for instance, likelihood of developing obesity overtime or unit costs of co-morbidities, using national surveys data are essential to improve the comparability and generalizability of future COI or economic evaluation studies. Finally, modeling the incidence-based lifetime costs and outcomes including direct and indirect costs from a societal perspective are essential to perform economic evaluation studies of obesity prevention programs.

We found heterogeneity in the scopes of cost analyses, including types of costs, numbers and types of related comorbidities, and BMI thresholds used. These inconsistences made it difficult to compare studies in different settings or to evaluate changes in economic burden of overweight and obesity over time. In addition, several types of costs were not determined, such as the out-of-pocket payment of households and individuals, or the costs of absenteeism to employers and employees. The varying scope of these cost analyses reflects the availability and accessibility of data sources at national and provincial levels. At the national level, Canadian Community Health Survey, National Population Health Survey and Economic Burden of Illness in Canada have good information to estimate the prevalence of obesity and its associated health care use and costs. To weigh future savings in health care costs against the costs for an obesity prevention program, an incidence-based COI analysis is required to estimate lifetime costs associated with weight status. A bottom-up costing approach and simulations using decision-analytical models are also necessary. None of the reviewed papers used longitudinal national data to estimate the changes in obesity or attempted to project total lifetime costs of obesity. This is partly due to the lack of longitudinal Canadian data on the development of weight-related health conditions and costs [26]. Nonetheless, the national data sources listed above might be used to project the changes in obesity epidemic at a population level. Further efforts to fully capture longitudinal changes in BMI trajectories and life-time costs are needed prior to economic evaluations of interventions for the prevention of obesity.

This review showed that indirect costs of obesity were substantial and account for about 45 to 60% of the total costs. Therefore, focusing solely on direct medical costs of obesity-related comorbidities does not fully capture the economic burden of the obesity epidemic. Estimating costs and monetary benefits from a societal perspective in an economic evaluation may provide a more complete picture.

Our review found only one cost analysis of a comprehensive school health program in Canada. The cost analysis was a 1-year assessment using a top-down approach. The paucity of data highlights the urgent need for cost analyses of existing and new prevention programs. When conducting an economic evaluation of an obesity prevention, considering only the savings due to reductions in excess weight does not provide a complete picture of the effect of the program. Some interventions may not change the weight status of individuals, but may still improve health status and ability to work. Second, reductions of health services utilization and health care costs as a result of an intervention might also be substantial. Consequently, in the design of an economic evaluation, the changes in costs and outcomes under intervention would also provide important additional information.

Conclusions

To conclude, we observed high costs associated with overweight and obesity and modest costs for obesity prevention programs; however, no cost-effectiveness study of obesity interventions has been performed in Canada. Cost-effectiveness analyses of preventive programs that constitute incidence-based life-time modeling of costs and health outcomes from societal perspective are urgently needed.

References

Shields M, Carroll MD, CL O: Adult obesity prevalence in Canada and the United States. NCHS data brief, no 56. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2011.

Reilly JJ, Methven E, McDowell ZC, Hacking B, Alexander D, Stewart L, Kelnar CJ: Health consequences of obesity. Arch Dis Child 2003, 88: 748–752. 10.1136/adc.88.9.748

Dietz WH: Health consequences of obesity in youth: childhood predictors of adult disease. Pediatrics 1998, 101: 518–525.

Thompson D, Edelsberg J, Colditz GA, Bird AP, Oster G: Lifetime health and economic consequences of obesity. Arch Intern Med 1999, 159: 2177–2183. 10.1001/archinte.159.18.2177

Trasande L, Elbel B: The economic burden placed on healthcare systems by childhood obesity. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2012, 12: 39–45. 10.1586/erp.11.93

Roux L, Donaldson C: Economics and obesity: costing the problem or evaluating solutions? Obes Res 2004, 12: 173–179. 10.1038/oby.2004.23

Kuhle S, Kirk S, Ohinmaa A, Yasui Y, Allen AC, Veugelers PJ: Use and cost of health services among overweight and obese Canadian children. Int J Pediatr Obes 2011, 6: 142–148. 10.3109/17477166.2010.486834

Janssen I, Lam M, Katzmarzyk PT: Influence of overweight and obesity on physician costs in adolescents and adults in Ontario, Canada. Obes Rev 2009, 10: 51–57. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00514.x

Wolfenstetter SB: Future direct and indirect costs of obesity and the influence of gaining weight: results from the MONICA/KORA cohort studies, 1995–2005. Econ Hum Biol 2012, 10: 127–138. 10.1016/j.ehb.2011.08.008

John J, Wolfenstetter SB, Wenig CM: An economic perspective on childhood obesity: recent findings on cost of illness and cost effectiveness of interventions. Nutrition 2012, 28: 829–839. 10.1016/j.nut.2011.11.016

Anis AH, Zhang W, Bansback N, Guh DP, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL: Obesity and overweight in Canada: an updated cost-of-illness study. Obes Rev 2009, 11: 31–40.

John J, Wenig CM, Wolfenstetter SB: Recent economic findings on childhood obesity: cost-of-illness and cost-effectiveness of interventions. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2010, 13: 305–313. 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328337fe18

Pelone F, Specchia ML, Veneziano MA, Capizzi S, Bucci S, Mancuso A, Ricciardi W, de Belvis AG: Economic impact of childhood obesity on health systems: a systematic review. Obes Rev 2012, 13: 431–440. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00968.x

Withrow D, Alter DA: The economic burden of obesity worldwide: a systematic review of the direct costs of obesity. Obes Rev 2011, 12: 131–141. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00712.x

Fung C, Kuhle S, Lu C, Purcell M, Schwartz M, Storey K, Veugelers PJ: From "best practice" to "next practice": the effectiveness of school-based health promotion in improving healthy eating and physical activity and preventing childhood obesity. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2012, 9: 27. 10.1186/1479-5868-9-27

Ross R, Blair SN, Godwin M, Hotz S, Katzmarzyk PT, Lam M, Levesque L, Macdonald S: Prevention and Reduction of Obesity through Active Living (PROACTIVE): rationale, design and methods. Br J Sports Med 2009, 43: 57–63.

Thomas H: Obesity prevention programs for children and youth: why are their results so modest? Health Educ Res 2006, 21: 783–795. 10.1093/her/cyl143

Ofman JJ, Sullivan SD, Neumann PJ, Chiou CF, Henning JM, Wade SW, Hay JW: Examining the value and quality of health economic analyses: implications of utilizing the QHES. J Manag Care Pharm 2003, 9: 53–61.

Au F, Prahardhi S, Shiell A: Reliability of two instruments for critical assessment of economic evaluations. Value Health 2008, 11: 435–439. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00255.x

Gerkens S, Crott R, Cleemput I, Thissen JP, Closon MC, Horsmans Y, Beguin C: Comparison of three instruments assessing the quality of economic evaluations: a practical exercise on economic evaluations of the surgical treatment of obesity. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2008, 24: 318–325.

Ohinmaa A, Langille JL, Jamieson S, Whitby C, Veugelers PJ: Costs of implementing and maintaining comprehensive school health: the case of the Annapolis Valley Health Promoting Schools program. Can J Public Health 2011, 102: 451–454.

Birmingham CL, Muller JL, Palepu A, Spinelli JJ, Anis AH: The cost of obesity in Canada. CMAJ 1999, 160: 483–488.

Patra J, Popova S, Rehm J, Bondy S, Flint R, Giesbrecht N: Economic Cost of Chronic Disease in Canada: 1995–2003. The Ontario Chronic Disease Prevention Alliance and the Ontario Public Health Association 2007. Available at (accessed on 01 May 2012) http://www.ocdpa.on.ca/OCDPA/docs/OCDPA_EconomicCosts.pdf

Finkelstein MM: Obesity, cigarette smoking and the cost of physicians' services in Ontario. Can J Public Health 2001, 92: 437–440.

Carter R, Moodie M, Markwick A, Magnus A, Vos T, Swinburn B, Haby MM: Assessing cost-effectiveness in obesity (ACE-obesity): an overview of the ACE approach, economic methods and cost results. BMC Public Health 2009, 9: 419. 10.1186/1471-2458-9-419

Moffatt E, Shack LG, Petz GJ, Sauve JK, Hayward K, Colman R: The cost of obesity and overweight in 2005: a case study of Alberta, Canada. Can J Public Health 2011, 102: 144–148.

Tarride JE, Haq M, Taylor VH, Sharma AM, Nakhai-Pour HR, O'Reilly D, Xie F, Dolovich L, Goeree R: Health status, hospitalizations, day procedures, and physician costs associated with body mass index (BMI) levels in Ontario, Canada. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2012, 4: 21–30.

Katzmarzyk PT, Janssen I: The economic costs associated with physical inactivity and obesity in Canada: an update. Can J Appl Physiol 2004, 29: 90–115. 10.1139/h04-008

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PV, SK, and AO initiated the research question. BXT and AVN did the literature search and synthesis. BXT and AO appraised the quality of studies. BXT, SK, AVN, AO, and PV wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Stefan Kuhle, Arto Ohinmaa contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Tran, B.X., Nair, A.V., Kuhle, S. et al. Cost analyses of obesity in Canada: scope, quality, and implications. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 11, 3 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-7547-11-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-7547-11-3