Abstract

Background

We sought to determine the frequency and distribution of cardiovascular comorbidities in a large cohort of low-income patients with diabetes who had received primary care for diabetes at municipal health clinics.

Methods

Outpatient data from the Philadelphia Health Care Centers was linked with hospital discharge data from all Pennsylvania hospitals and death certificates.

Results

Among 10,095 primary care patients with diabetes, with a mean observation period of 4.6 years (2.8 after diabetes diagnosis), 2,693 (14.3%) were diagnosed with heart disease, including 270 (1.4%) with myocardial infarction and 912 (4.8%) with congestive heart failure. Cerebrovascular disease was diagnosed in 588 patients (3.1%). Over 77% of diabetic patients were diagnosed with hypertension. Incidence rates of new complications ranged from 0.6 per 100 person years for myocardial infarction to 26.5 per 100 person years for hypertension. Non-Hispanic whites had higher rates of myocardial infarction, and Hispanics and Asians had fewer comorbid conditions than African Americans and non-Hispanic whites.

Conclusion

Cardiovascular comorbidities were common both before and after diabetes diagnosis in this low-income cohort, but not substantially different from mixed-income managed care populations, perhaps as a consequence of access to primary care and pharmacy services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Patients with diabetes are at increased risk of a wide range of complications and comorbidities, which adversely affect quality of life, mortality, and health care services utilization. Cardiovascular diseases are the primary causes of morbidity and mortality among patients with diabetes, yet data on cardiovascular disease among patients with diabetes are limited [1]. Although microvascular pathologies, including retinopathy and nephropathy, have been shown to be strongly associated with glycemic control, macrovascular complications, including heart disease and cerebrovascular disease, appear to be less responsive to glycemic control, and strategies to reduce them are focussed on controlling other risk factors such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, smoking, and obesity [2]. This complex array of risk factors and outcomes makes diabetes care exceptionally demanding both for patients and for health care providers.

Data on the prevalence and incidence of macrovascular comorbidities are largely derived either from clinical trials with selected patient populations, self-reported cross-sectional survey data, or managed-care studies of insured patients of higher socioeconomic status. The rising prevalence of diabetes in low-income inner-city populations underscores the need to understand the frequency with which these comorbidities occur in such populations and to assess possible disparities in their occurrence.

The Philadelphia Health Care Centers (HCCs) provide primary care and pharmacy services to approximately 100,000 patients annually through eight neighborhood centers and one sexually transmitted disease clinic. Individual patients are not billed for any services provided. Although the HCCs are available to all Philadelphia residents, their patients are almost universally low-income; over 60% have no health insurance. A majority of HCC patients are African American, but there are also substantial numbers of non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, and Asian patients. Diabetes is one of the most common diagnoses among adult HCC patients. Since to our knowledge no previous study has reported the prevalence or incidence of cardiovascular diseases in a comparable, ethnically diverse, low-income diabetic population, we sought to determine the frequency and distribution of cardiovascular comorbidities among HCC patients with diabetes.

Methods

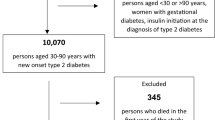

The Urban Diabetics Study cohort consists of 10,095 patients diagnosed with diabetes in the HCCs between January 1, 1996 and December 31, 2001. All diabetic patients were included except those for whom Social Security numbers were unavailable (less than 6% of all diabetic patients). All HCC visits between March 1, 1993 and December 31, 2001, all hospital discharges from any Pennsylvania hospital between January 1, 1993 and December 31, 2001, and death records have been linked for these patients. The data includes outpatient visits and hospitalizations both before and after the initial diabetes diagnosis, within the study time period. Race/ethnicity was classified based on the outpatient records. Diabetes incidence was calculated based on the admission date of the first hospitalization for which a diabetes diagnosis was recorded or the date of the first HCC outpatient visit for which a diabetes diagnosis was recorded, whichever came first.

The cardiovascular comorbidities assessed included any heart disease (ICD9 codes 402 and 410–429, ICD10 codes I5-I9, I11, I13, I20-I27, and I30-I52), myocardial infarction (MI) (ICD9 code 410, ICD10 codes I21-I23), congestive heart failure (CHF) (ICD9 code 428, ICD10 code I50), cerebrovascular disease (ICD9 codes 430–438, ICD10 code I6), and hypertension (ICD9 codes 401–405, ICD10 codes I10-I15). For each comorbid condition we assessed baseline prevalence at or before first diabetes diagnosis, incidence rate per 100 person-years of follow-up time following first diabetes diagnosis among those free of the condition at baseline, and cumulative prevalence, i.e., any occurrence over the course of the observation period. Logistic regression and proportional hazards regression were used to simultaneously assess multiple demographic risk factors, including sex, race/ethnicity, exact age, and year of diabetes incidence. Patients with unknown race/ethnicity (n = 7) were excluded from multivariable analyses.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the 10,095 patients included are shown in Table 1. Mean age at diabetes diagnosis was 49.2 years, and mean observation period was 4.59 years, including 1.74 years before and 2.85 years after first known diabetes diagnosis. Among the patients for whom income was ascertained, median income was $7,092; 86% had annual incomes below $15,000. Table 2 shows which of the linked data sources provided diagnoses of each comorbidity.

Heart disease

Baseline prevalence of any heart disease was 14.8 %, including 4.1% with CHF and 1.0% with MI (Table 3). In multiple regression analyses, non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity (compared to the African-American reference group) was associated with substantially higher baseline prevalence of MI (Table 4). Hispanic race/ethnicity was associated with lower baseline prevalence of CHF, and Asian race/ethnicity was associated with lower baseline prevalences of MI, CHF, and any heart disease. Age and male sex were positively associated with baseline prevalence of MI, CHF, and any heart disease. Year of diabetes diagnosis was negatively associated with baseline prevalence of MI, CHF, and any heart disease, indicating that baseline prevalences declined between 1996 and 2001.

Incidence of heart disease, among those who had not been diagnosed with it at the time of their diabetes diagnosis, was 5.36 cases per 100 person-years, with 13.9% of those at risk being diagnosed before the end of the study period (Table 3). Incidence of MI was 0.59 per 100 person-years. Incidence of CHF was 1.85 per 100 person-years. In multiple regression analyses (Table 5), Non-Hispanic whites, as compared to African-Americans, were at higher risk of MI and all heart disease. Hispanic and Asian patients were at lower risk of CHF. Incidence of heart disease increased slightly with later year of diabetes diagnosis. Age at diabetes diagnosis was associated with higher incidence of all heart disease outcomes, as was male sex.

Through the entire study period, 2,693 patients (26.7%) were diagnosed with heart disease (Table 3). MI was diagnosed in 270 patients (2.7%) and CHF in 912 (9.0%). In multiple regression analyses (Table 6), Non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity was associated with higher cumulative prevalence of MI (odds ratio [OR] 1.90) and any heart disease (OR 1.32). Hispanic race/ethnicity was associated with lower cumulative prevalence of CHF and any heart disease (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.66–0.91). Asian race/ethnicity was associated with lower cumulative prevalences of all heart disease outcomes. Age at baseline and male sex were positively associated with cumulative prevalence of MI, CHF, and any heart disease. Year of diabetes diagnosis was negatively associated with cumulative prevalence of each of the heart disease outcomes.

Cerebrovascular disease

Cerebrovascular disease was diagnosed in 588 patients, evenly split between cases diagnosed at baseline and incident cases subsequent to diabetes incidence (Table 3). Baseline prevalence of cerebrovascular disease was 2.9%. In multiple regression analyses (Table 4), Hispanic, Asian, and "other" race/ethnicities were associated with lower baseline prevalences of cerebrovascular disease. Age at baseline and male sex were positively associated with baseline prevalence of cerebrovascular disease, while year of diabetes diagnosis was negatively associated with baseline prevalence of cerebrovascular disease (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.74–0.83).

The incidence rate for cerebrovascular disease, among those free of it at baseline diabetes diagnosis, was 1.07 per 100 person-years. In multiple regression analyses, only Hispanic race/ethnicity was associated with lower risk. Age was the only variable associated with a higher incidence of cerebrovascular disease.

Cumulative prevalence of cerebrovascular disease was 5.8%. Hispanic and Asian race/ethnicities were associated with lower cumulative prevalences of cerebrovascular disease, as was year of diabetes diagnosis. Age at baseline and male sex were positively associated with cumulative prevalence of cerebrovascular disease.

Hypertension

A majority of patients (51.8%) had a diagnosis of hypertension at baseline (Table 3). Non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, Asian, and "other" race/ethnicities were all associated with lower baseline prevalence of hypertension, as was male sex (Table 4). Age and year of diabetes diagnosis were associated with higher baseline prevalence.

An additional 2,578 patients were diagnosed with hypertension after diabetes diagnosis, for a cumulative prevalence of 7,804 (77.3%). The incidence rate was 26.46 cases per 100 person-years. Non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, Asian, and "other" race/ethnicities were all associated with lower incidence of hypertension than the African-American reference group, while age and later date of diabetes diagnosis were associated with higher incidence.

Cumulative prevalence of hypertension was negatively associated with non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, Asian, and "other" race/ethnicities, male sex and year of diabetes diagnosis, and positively associated with age.

Discussion

Patients in the Urban Diabetics Study cohort, like other diabetic patient populations, faced a substantial burden of cardiovascular comorbidity. Many were affected by comorbid conditions before they were diagnosed with diabetes, including 14.8% with preexisting heart disease, 2.9% with preexisting cerebrovascular disease, and 51.8% with preexisting hypertension. Among those free of these comorbidities at the time of diabetes diagnosis, similar proportions went on to develop them during followup.

The diabetic patients served by the Philadelphia HCCs are almost uniformly low-income and uninsured or underinsured. A large majority are African American. Nonetheless, the prevalence and incidence of major cardiovascular complications does not, in general, appear to exceed the rates of these complications in other patient populations, whether assessed in nationally-representative surveys or in insured, predominantly middle class managed care populations. Disparities associated with race/ethnicity were in varying directions. Non-Hispanic whites had lower rates of hypertension than African Americans but higher rates of heart disease, especially MI, while Asians and Hispanics had more favorable outcomes on several measures.

As expected, age was positively associated with all cardiovascular comorbidities. Male sex was associated with higher incidence and prevalence of all comorbidities except hypertension.

These findings are comparable to those for other diabetic populations not limited to low-income or uninsured patients. The cumulative prevalence of any heart disease in this study population (26.7%) was similar to the 24.5% prevalence of self-reported coronary heart disease among diabetic patients in the nationally representative 1999–2001 National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS), while the cumulative prevalence of cerebrovascular disease in our study (5.8%) was substantially lower than self-reported stroke in the NHIS sample (9.3%) [3]. However, the age distribution of diabetics in the NHIS sample was substantially older than in this population. If the comparison is restricted to NHIS diabetic patients age 35–64, national prevalences were 31% lower than in our population for heart disease (18.4% vs. 26.7%) and almost identical for cerebrovascular disease (5.9% vs. 5.8%). The overall incidence rate of MI (0.59 per 100 person-years) in the Urban Diabetics cohort was lower than that in the Kaiser Permanente managed care population studied by Karter, et al. [4]. Again, this may reflect the fact that the Urban Diabetics cohort was younger (mean age 49.2 years vs. 59.8 years). When the overall incidence rate in our population is multiplied by the hazard ratio for 10 years additional age in our study, the result (0.92 per 100 person-years) is almost identical to the age- and sex-adjusted rate for African Americans reported by Karter, et al. (0.91 per 100 person-years). The incidence rate of CHF, on the other hand, was higher in our population than in studies of Kaiser Permanente patients [5], while that of cerebrovascular disease was similar to the incidence of stroke reported by Karter, et al. Another study conducted with the Kaiser Permanente diabetes patients found evidence of hypertension for 74% of those diagnosed with diabetes [6], similar to the 77% cumulative prevalence in the Urban Diabetics study.

Other studies have reported somewhat divergent findings for heart disease [7, 8] and cerebrovascular disease [9–11], but these studies involved either younger type 1 diabetic patients [7], earlier time periods [8], an older population [9], or analyses that excluded some patients with prior histories of cardiovascular disease [10, 11]. Several studies have reported high rates of hypertension among diabetic patients, although none as high as the cumulative prevalence in this cohort [9, 11–14].

Many of our findings on racial/ethnic differences in the incidence of MI, CHF, and cerebrovascular disease among diabetic patients are also similar to those found by Karter, et al. Like them, we found higher risks of MI for non-Hispanic whites than for other groups, and lower risks of CHF and cerebrovascular disease for Hispanics and Asians than for African Americans and non-Hispanic whites. The magnitudes of the differences between African-American and non-Hispanic white rates were broadly similar between the two studies, while rates for Asians and Hispanics were more variable. The 1999–2001 NHIS also found the prevalence of coronary and other heart disease among patients with diabetes (based on self-reported data) highest among non-Hispanic whites and lowest among Hispanics (rates for Asians were not reported) [3]. Unlike our study, the NHIS analyses found rates of cerebrovascular disease higher among African Americans with diabetes than among either Hispanics or non-Hispanic whites. Among diabetic patients in the Veterans Health Administration, rates of cardiovascular disease were lower for African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians than for non-Hispanic whites [9]. However, that study was restricted to patients with at least 4 outpatient clinic visits in a 12-month period, and race/ethnicity was not ascertained for 21.4% of the patients in that study, leaving considerable potential for bias in these results.

In our study, male sex was associated with higher baseline prevalence of all comorbidities, higher incidence of the heart disease comorbidities, and higher cumulative prevalence of all comorbidities except hypertension. Our findings are broadly consistent with those in other diabetic populations [3, 4, 15].

The similarities of our findings to those from the Kaiser Permanente studies are striking, given that the latter assessed an insured, West Coast cohort in which most Hispanics were Mexican American [4], while our study population was an overwhelmingly poor, uninsured or underinsured, East Coast cohort in which most Hispanics were Puerto Rican. The national origins of the Asian patients in the two studies probably also differ, as the Philadelphia Asian community includes larger proportions of South and Southeast Asians and smaller proportions of Japanese and Filipino individuals than the Asian communities of northern California [16]. Among both Hispanics and Asian Americans, national groups vary widely in socioeconomic status and health outcomes [17–19].

Our study is based on administrative records from several sources, each of which may contain errors, and is unlikely to capture as many cardiovascular endpoints than studies with study-specific, patient-level data collection [20, 21]. Because the outpatient encounter forms allowed a maximum of four diagnostic codes, there may have been underreporting of some comorbidities, although cardiovascular disease was unlikely to go unrecorded. Outpatient care outside of the eight Philadelphia HCCs and hospitalizations outside of Pennsylvania were not ascertained. The design of the study could therefore undercount comorbid conditions and cardiovascular endpoints for patients who acquired health insurance or moved out of the city and therefore changed outpatient providers. As a test of the sensitivity of the results to migration in and out of the health system, we repeated the analyses, restricting the follow-up time from the dates of the first to the last to outpatient visit; the results were not materially changed.

Among the strengths of the study are its inclusion of a wide range of complications, 8+ year longitudinal design, large sample size, and the combination of data sources to enhance endpoint ascertainment. Our design captured diabetes diagnoses and cardiovascular comorbidity and endpoint data from three complementary sources: outpatient visits in any of the eight Philadelphia HCCs, inpatient visits within any hospital in Pennsylvania and death certificate records. Table 2 supports the observation of Kashner and colleagues that the addition of outpatient administrative data resulted in significantly higher estimates of comorbidity prevalence, strongly suggesting that it has value as an additional data source [22].

By limiting the study to patients with an initial diabetes diagnosis after the first 34 months for which we have data, we were able to ascertain the prevalence of cardiovascular conditions before and at the time of diabetes diagnosis as well as incident conditions diagnosed after diabetes incidence. We are unaware of any study that has presented similar data except for one limited to elderly African Americans and whites in North Carolina, which included only 653 patients with diabetes [23]. The fact that patients included in the study had no record of a diabetes diagnosis either in the Philadelphia Health Care Centers or in a hospital discharge record between March 1993 and the date of their diabetes diagnosis, which was no earlier than January 1996, should ensure that the great majority of patients included here were incident diabetes cases.

There is a strong, well-established association between socioeconomic disadvantage and cardiovascular disease in industrialized populations [24], including diabetic populations [25]. The absence of excess cardiovascular disease beyond that experienced in other diabetic patient populations in this disadvantaged cohort suggests that some factor has offset this disadvantage for this cohort. One possibility is that the provision of primary care, other outpatient services to which patients are referred by their primary care physicians, and prescription medications without out-of-pocket costs to all patients in the Philadelphia HCCs removes a significant barrier to effective care. Restricted use of medications due to costs is common [26] and has been shown to lead to poorer outcomes for several chronic diseases, including cardiovascular diseases [27, 28].

This is the only study of which we are aware to report on cardiovascular comorbidity in a large, ethnically diverse cohort of low-income patients with diabetes with near-universal ascertainment of race/ethnicity. It includes substantial populations of low-income Asians, Hispanics, and non-Hispanic whites as well as African Americans, and allows comparisons of the experiences of these groups. The data is longitudinal and includes both outpatient and hospital discharges over an extended period. By looking at comorbid conditions both before and after diabetes incidence, we have provided both a picture of the health status of these patients at the initial presentation of diabetes and estimates of the incidence of additional comorbidities while being treated for diabetes.

Conclusions

Cardiovascular comorbidities were common both before and after diabetes diagnosis in this low-income cohort, but not substantially different from mixed-income managed care populations. It is possible that access to primary care and pharmacy services without fees to individuals in this public health clinic system prevented the poorer outcomes usually seen for disadvantaged patients.

References

Engelgau MM, Geiss LS, Saaddine JB, Boyle JP, Benjamin SM, Gregg EW, Tierney EF, Rios-Burrows N, Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Imperatore G, Narayan V: The evolving diabetes burden in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2004, 140: 945-950.

Goldberg RB: Cardiovascular disease in patients who have diabetes. Cardiology Clinics. 2003, 21: 399-413.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Self-reported heart disease and stroke among adults with and without diabetes – United States, 1999–2001. MMWR Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 2003, 52: 1065-70.

Karter AJ, Ferrara A, Liu JY, Moffet HH, Ackerson LM, Selby JV: Ethnic disparities in diabetic complications in an insured population. JAMA. 2002, 287: 2519-2527. 10.1001/jama.287.19.2519.

Iribarren C, Karter AJ, Go AS, Ferrara A, Liu JY, Sidney S, Selby JV: Glycemic control and heart failure among adult patients with diabetes. Circulation. 2001, 103: 2668-2673.

Selby JV, Peng T, Karter AJ, Alexander M, Sidney S, Lian J, Arnold A, Pettitt D: High rates of co-occurrence of hypertension, elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and diabetes mellitus in a large managed care population. Am J Manag Care. 2004, 10: 163-170.

Zgibor JC, Songer TJ, Kelsey SF, Drash AL, Orchard TJ: Influence of health care providers on the development of diabetes complications: long-term follow-up from the Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications Study. Diabetes Care. 2002, 25: 1584-1590.

Wingard DL, Barrett-Connor E: Heart disease and diabetes. Diabetes in America. Edited by: National Diabetes Data Group. 1995, Washington, DC: US Govt Printing Office (NIH publ no 95-1468), 429-448. 2

Young BA, Maynard C, Boyko EJ: Racial differences in diabetic nephropathy, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in a national population of veterans. Diabetes Care. 2003, 26 (8): 2392-2399.

Kothari V, Stevens RJ, Adler AI, Stratton IM, Manley SE, Neil A, Holman RR: Risk of stroke in type 2 diabetes estimated by the UK Prospective Diabetes Study risk engine. Stroke. 2002, 33: 1776-1781. 10.1161/01.STR.0000020091.07144.C7.

Lee CD, Folsom AR, Pankow JS, Brancati FL: Cardiovascular events in diabetic and nondiabetic adults with or without history of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2004, 109: 855-860. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000116389.61864.DE.

Baumann LC, Chang MW, Hoebeke R: Clinical outcomes for low-income adults with hypertension and diabetes. Nursing Research. 2002, 51: 191-198. 10.1097/00006199-200205000-00008.

Spijkerman AMW, Adriaanse MC, Dekker JM, Nijpels G, Stehouwer CDA, Bouter LM, Heine RJ: Diabetic patients detected by population-based stepwise screening already have a diabetic cardiovascular risk profile. Diabetes Care. 2002, 25: 1784-1789.

Klein BEK, Klein R, Lee KE: Components of the metabolic syndrome and risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes in Beaver Dam. Diabetes Care. 2002, 25: 1790-1794.

Barzilay JI, Spiekerman CF, Kuller LH, Burke GL, Bittner V, Gottdiener JS, Brancati FL, Orchard TJ, O'Leary DH, Savage PJ: Prevalence of clinical and isolated subclinical cardiovascular disease in older adults with glucose disorders: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Diabetes Care. 2001, 24: 1233-1239.

Census 2000 Summary File 3. [http://www.census.gov]

Arias E, Anderson RN, Hsiang-Ching K, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD: Deaths:Final data for 2001. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2003, 52 (3): 1-115.

Anand SS, Yusuf S, Vuksan V, Devanesen S, Teo KK, Montague PA, Kelemen L, Yi C, Lonn E, Gerstein H, Hegele RA, McQueen M: Differences in risk factors, atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease between ethnic groups in Canada: the study of health assessment and risk in ethnic groups (SHARE). Indian Heart J. 2000, 52 (Suppl 7): S35-43.

Klatsky A: The risk of hospitalization for ischemic heart disease among Asian Americans in Northern California. Am J Public Health. 1994, 84: 1672-1675.

Ballantyne CM, Hoogeveen RC, Bang H, Coresh J, Folsom AR, Heiss G, Sharrett AR: Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and risk for incident coronary heart disease in middle-aged men and women in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Circulation. 2004, 109: 837-842. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000116763.91992.F1.

Burt VL, Cutler JA, Higgins M, Horan MJ, Labarthe D, Whelton P, Brown C, Roccella EJ: Trends in the prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the adult US population. Data from the health examination surveys, 1960 to 1991. Hypertension. 1995, 26: 60-69.

Kashner TM: Agreement between administrative files and written medical records: a case of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Care. 1998, 36: 1324-1336. 10.1097/00005650-199809000-00005.

Fillenbaum GG, Pieper CF, Cohen HD, Cornoni-Huntley JC, Guralnik J: Comorbidity of five chronic health conditions in elderly community residents: determinants and impact on mortality. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000, 55 (2): M84-M89.

Kaplan GA, Keil JE: Socioeconomic factors and cardiovascular disease: a review of the literature. Circulation. 1993, 88 (4 Pt 1): 1973-1998.

Bachmann MO, Eachus J, Hopper CD, Davey Smith G, Propper C, Pearson NJ, Williams S, Tallon D, Frankel S: Socio-economic inequalities in diabetes complications, control, attitudes and health service use: a cross-sectional study. Diabet Med. 2003, 20: 921-929. 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.01050.x.

Artz MB, Hadsall RS, Schondelmeyer SW: Impact of generosity level of outpatient prescription drug coverage on prescription drug events and expenditure among older persons. Am J Public Health. 2002, 92: 1257-1263.

Tamblyn R, Laprise R, Hanley JA, Abrahamowicz M, Scott S, Mayo N, Hurley J, Grad R, Latimer E, Perreault R, McLeod P, Huang A, Larochelle P, Mallet L: Adverse events associated with prescription drug cost-sharing among poor and elderly persons. JAMA. 2001, 285: 421-429. 10.1001/jama.285.4.421.

Heisler M, Langa KM, Eby EL, Fendrick AM, Kabeto MU, Piette JD: The health effects of restricting prescription medication use because of cost. Med Care. 2004, 42: 626-34. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000129352.36733.cc.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/5/15/prepub

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grant #R21DK064201-01 from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JMR and DAW conceived the study and obtained the data. JMR designed the study, performed the analyses, and drafted the manuscript. DAW and CNS revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Robbins, J.M., Webb, D.A. & Sciamanna, C.N. Cardiovascular comorbidities among public health clinic patients with diabetes: the Urban Diabetics Study. BMC Public Health 5, 15 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-5-15

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-5-15