Abstract

The burden of type 2 diabetes is growing, not only through increased incidence, but also through its comorbidities. Concordant comorbidities for type 2 diabetes, such as cardiovascular diseases, are considered expected outcomes of the disease or disease complications, while discordant comorbidities are not considered to be directly related to type 2 diabetes and are less extensively addressed under diabetes management. Here we show that the combination of concordant and discordant comorbidities appears frequently in persons with diabetes (75%). Persons with combined comorbidities visited family physicians more than persons with discordant, concordant or no comorbidity (17.3 ± 10.2, 11.6 ± 6.5, 8.7 ± 6.8, 6.3 ± 6.6 visits/person/year respectively, p < 0.0001). The risk of death during the study period was highest in persons with combined comorbidities and discordant only comorbidities (HR = 33.4; 95% CI 12.5–89.2 and HR = 33.5; 95% CI 11.7–95.8), emphasizing the contribution of discordant comorbidities to the outcome. Our study is unique as a long-term follow-up of an 11-year cohort of 9725 persons with new-onset type 2 diabetes. The findings highlight the contribution of discordant comorbidity to the burden of the disease. The high prevalence of the combination of both concordant and discordant comorbidities, and their appearance before the onset of type 2 diabetes, indicates a continuum of morbidity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Introduction

The prevalence of chronic diseases has increased dramatically in developed countries in recent decades1. Parallel to the increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes, the burden of the disease and its comorbidities has become a growing concern for health providers2. The clustering of chronic diseases, known as multimorbidity, is common in type 2 diabetes3,4, and contributes substantially to the burden of the disease5. Advanced age, female gender and low socioeconomic status (SES) have been found to be associated with higher rates of multimorbidity3,4,6.

Some diseases, such as hypertension, ischemic heart disease, nephropathy and retinopathy, are considered concordant to diabetes, since they represent parts of the same pathophysiologic risk profile and are considered expected outcomes of the disease or disease complications. Other diseases, such as depression, rheumatologic diseases, chronic lung disease and malignant diseases6,7, are considered "discordant" to diabetes, as they are not directly related to the pathogenesis of diabetes and do not share similar risk factors. The risks of both concordant and discordant comorbidities increase with time in persons with type 2 diabetes6. Concordant comorbidities, such as cardiovascular diseases, are treated as part of the detailed protocol of care for diabetes management and are more likely to be the focus of the disease management plan7. In contrast, discordant comorbidities are less extensively addressed under diabetes management7.

Piette and Kerry elaborated on the substantial contribution of discordant comorbidities to health outcomes8. A number of subsequent studies reported that concordant diseases are more easily managed than discordant diseases, with better outcomes9,10. Managing multimorbidity in routine clinical practice is challenging. Among the difficulties facing family physicians are the differences in guidelines for various diseases, time constraints, and patients' difficulty in performing self-care for several diseases at the same time7,10. Previous research has described the impact of multimorbidity on the health system, addressing the high use of health services8,9, in cross-sectional11 and short-term cohort studies12.

Objective

In this study, we followed a cohort of persons from the time of onset of type 2 diabetes for a period of 11 years. We assessed the utilization of health services and mortality risk according to the classification of concordant and discordant comorbidity.

Results

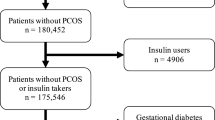

The study sample included 9725 persons who were identified during 2007 as having newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes according to the criteria delineated in the Methods (Fig. 1). The follow-up period lasted 9.7 ± 2.2 years/person, which contributed to the study’s 94,260 person years. After the first year, and until the end of the follow-up, 1785 (18%) persons died. Men comprised 52% of the cohort. The mean age at diabetes diagnosis was 58 ± 13 years, nearly half of the persons were aged 45–65 years and one third were aged 65 years and older (Table 1). The study sample comprised 54% Jews and 46% Arabs (Table 1). We identified 6.3 ± 3.8 diseases per person (Table 1). For 79% (n = 7209) of the persons in the cohort, comorbidities were detected both before and after diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. Lower rates were recorded for persons with comorbidities diagnosed only before (13%) or only after (8%) the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes.

Characteristics of persons with concordant and discordant comorbidities

Diseases were grouped into concordant and discordant comorbidities according to the bodily systems affected (see Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 online). Persons with a combination of both concordant and discordant comorbidities, referred to here as “combined comorbidity”, were more prevalent (n = 7316; 75%) compared to persons with concordant only or discordant only comorbidities (16.6% and 2.5%, respectively). No comorbidity was reported in 549 (5.6%) persons. Men were more represented than women in all groups of comorbidities (Table 1). Persons aged 45–65 years at the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes were most highly represented in all comorbidity groups. Jews were dominant in the group of discordant comorbidities only (70%) and Arabs were dominant in the group of concordant comorbidities only (58%). Persons without an exemption from national health insurance payments were dominant in all groups of comorbidities (Table 1). The number of comorbidities per person was highest in the group of persons with combined comorbidities, compared to persons with concordant only or discordant only comorbidities (7.3 ± 3.6, 2.8 ± 1.6, 2.0 ± 1.3 respectively), with a gap remaining between the number of comorbidities before and after the onset of type 2 diabetes (Table 1). The distribution of the number of diseases between groups was different; in the groups of persons with concordant only or discordant only comorbidities, more persons had few diseases, while in the group of combined comorbidities, there was a broader range of diseases (Fig. 2).

A multinomial logistic regression model was designed to assess the risk of having any type of comorbidity of type 2 diabetes, considering the parameters of gender, age at onset of diabetes type 2, ethnic origin, smoking and exemption from national health insurance payments (Table 2). The reference group was persons without any comorbidity. Compared to persons aged 30–45 years at the onset of type 2 diabetes, those aged 45–65 years were at higher risk for having combined comorbidities [OR = 4.9; 95% CI 3.9–6.2), as were those aged 65 years or more [OR = 4.8; 95% CI 3.8–6.1]. Jews had a lower risk of having combined comorbidity compared to Arabs [OR = 0.2; 95% CI 0.2–0.3], similar to other groups of comorbidity. Women were at lower risk than men for having combined comorbidity [OR = 0.87; 95% CI 0.7–1.0], similar to other types of comorbidities. People with an exemption from social insurance payments had the same risk as those without it (Table 2).

Comorbidities and utilization of health services

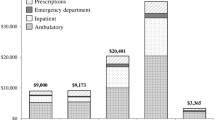

‘Visits to family physicians’ was the most utilized health service during the study period, compared to visits to consultants and hospitalizations. Visits to family physicians were performed more by persons with combined comorbidities compared to persons with concordant only or discordant only comorbidities and persons without comorbidities (17.3 ± 10.2, 11.6 ± 6.5, 8.7 ± 6.8 and 6.3 ± 6.6 visits/person/year respectively, p < 0.0001) (see Supplementary Table S3 online).

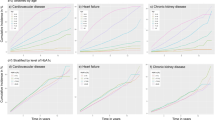

The trend of annual use of health services presents differences between groups throughout the study period. Persons with combined comorbidity used them more than persons from other groups, and persons without comorbidity used them less than others; the differences between the groups were maintained over time (Figs. 3A–C). A downward trend in annual visits was observed among persons without comorbidities. Differences in hospitalization were steady throughout most of the study period with a tendency to rise in all groups, except in persons without comorbidity (Fig. 3C).

Comorbidities and mortality

During the study period, 1785 (18%) persons died. The rate of death was highest among persons with combined comorbidity, followed by persons with discordant only comorbidities and concordant only comorbidities, and lowest among persons without comorbidity (23%, 11.5%, 4.3% and 0.7% respectively, p < 0.0001) (Table 1).

Incidence rates of death per 100 person years were 2.4 (95% CI 2.3–2.5), 1.2 (95% CI 0.7–1.6), 0.4 (95% CI 0.3–0.5) and 0.1 (95% CI 0.0–0.1), respectively.

Persons who died were more often older, Jews, smokers, and had more comorbidities than those who survived (see Supplementary Table 4 online). We performed a Cox regression analysis for risk of all-cause death, considering sex, age, ethnic origin, smoking and exemption from national health insurance payments. The reference group was persons who did not die. Persons with combined comorbidities and persons with discordant only comorbidities had a similarly higher risk of death [HR = 33.45; 95% CI 12.5–89.2 and HR = 33.48; 95% CI 11.7–95.8, respectively] than persons without comorbidities. Persons with concordant only comorbidities also had a higher risk of death [HR = 10.37; 95% CI 3.8–28.4], albeit lower than for persons with combined or discordant only comorbidities. Age 65 years and older at the onset of diabetes type 2 conferred a higher risk of death [HR = 14.7; 95% CI 10.75–20.22] than age 30–45 years. To a lesser extent, age 45–65 years also conferred a higher risk than age 30–45 years [HR = 3.2; 95% CI 2.3–4.4]. Women had a lower risk of death than men [HR = 0.8; 95% CI 0.7–0.9] (Table 3). No differences in risk of death were observed between Arabs and Jews, smokers and non-smokers, or between persons having or not having an exemption from national health insurance payments.

We plotted the Kaplan–Meier curve to describe survival probabilities by comorbidity groups during the study period (Fig. 4). The steepest slope was observed in the group of persons with combined comorbidities, while the group of persons with discordant comorbidity only had a steeper slope than that of persons with concordant comorbidity only. The graph describing survival probabilities in the group of persons with no comorbidity was remarkably stable throughout the follow-up.

Discussion

In this study of a large health maintenance organization, we followed persons from the time of onset of type 2 diabetes. At this time, most of the persons already exhibited other comorbidities. There were more individuals with both concordant and discordant comorbidities of type 2 diabetes than with either concordant or discordant comorbidities alone. The risk of all-cause death was highest in persons with combined comorbidity and in persons with discordant only comorbidities, indicating the contribution of discordant comorbidities to the outcome.

We defined the onset of type 2 diabetes as the starting point of our study, but we soon realized that the most common situation is that comorbidities, both concordant and discordant, appear before and after the onset of type 2 diabetes. The demonstration of prevalent comorbidities at the onset of diabetes corroborates previous reports6,7,13. This may be explained, at least in part, by the risk factors shared by type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases, such as the metabolic syndrome14. The essence of type 2 diabetes may be a sequence of events in the development of comorbidities, rather than a definitive starting point.

The association of advanced age with comorbidities in persons with diabetes concurs with previous reports3,4. In our study, older age was associated with risk for both comorbidity and death.

Our study sample is characterized by near equal gender distribution; men had a higher risk for comorbidity and for death. A previous study reported higher prevalence in women than men of comorbidity in general, but not specifically of diabetes3.

Exemption from national health insurance payments, indicating low SES, was not associated with comorbidity and its outcomes, unlike previous findings3,4. This difference may be attributed to the national health insurance in Israel, which includes primary care services and hospitalization free of charge.

Arab ethnic origin was associated with higher risk for all categories of comorbidity. Considering cardiovascular diseases, which is the dominant concordance comorbidity, the outcome is in line with previous reports in Israel, of generally higher rates of cardiovascular diseases among Arabs than among Jews15,16,17. A novel aspect of the current study is the report of a higher rate of discordant comorbidity in the Arab population in Israel.

In our study, persons with combined comorbidities of type 2 diabetes consistently used health services more frequently than did persons with only concordant or discordant comorbidities. ‘Visits to family doctors’ was the health service most used in the community, more so among persons with combined comorbidity. The same trend was observed for hospitalization. Interestingly, among persons without comorbidities, the use of health services declined during the follow-up period. This could be due to better health or self-care. Our findings corroborate a report, based on private insurance company claims, of higher health service costs among persons with combined comorbidities than among persons with either discordant or concordant diseases alone18. In contrast to that study, our study is based on data from the national insurance health system. A recent publication from the Netherlands also reported higher societal costs of persons with diabetes and lower utilities19.

The death rate was higher in persons with combined comorbidities of type 2 diabetes, compared to only concordant or discordant comorbidities, or no comorbidities. The risk of death was similar for persons with combined comorbidities and discordant only comorbidities, although persons with discordant comorbidities only had fewer diseases. This raises the issue of the contribution of specific diseases, which is not addressed in our study. This may be consequent to the inclusion of malignant diseases in our study. Comorbidity of malignant diseases in persons with diabetes has been previously reported, and partly explained by shared risk factors20,21.

Other parameters that were identified as carrying higher risk for death in persons with type 2 diabetes were age 45 years and older, and male gender, in addition to comorbidities. Our study did not find Arab background to be an independent risk factor for mortality. Previous studies reported higher rates of all-cause mortality among Arabs, particular with respect to cardiovascular diseases22,23. However, combined comorbidities as defined herein were not reported in those studies.

We have not found another community-based study that compared mortality rates by concordance of comorbidities of type 2 diabetes. Previous publications that reported mortality in persons with diabetes focused on trends of mortality, showing that the decline in persons with diabetes lags behind those without diabetes24,25,26.

The strengths of our study include the long-term follow-up from the year of diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, the considerable sample size, and the real-life data of persons in the community. The large sample enabled us to draw conclusions regarding specific modes of the disease. This study is based on robust, valid sources of information, including the Clalit Health Services (CHS) chronic disease register, which is comprehensive and continuously updated27 with ongoing updated quality measures28.

Our study is limited by the crudeness of the data on type 2 diabetes, without accounting for specific diagnosis or severity of diseases, or for the individual level of control of type 2 diabetes or other chronic diseases. All-cause death was a study outcome, and not a specific cause of death. This is because the reason for death is not identified in the CHS registers. The analysis of death events using the Cox model was limited by the few cases recorded in the group of persons without comorbidities, which served as a reference group. As a result, the assumption of proportionality which underlies the Cox model was not met. Still, we consider it sensible to use the Cox model to examine the hazard as a function of the tested parameters during the study period.

Our data included services within the framework of public services. We do not have information on the use of private services, which could be relevant mainly for consultations. Our data did not include social information such as education or income. Instead, we used the exemption from national health insurance payments as an indicator of low SES. Since Israel operates a national health insurance system that provides services equally to all citizens, exemption from payment is an indirect indicator of SES. The health services assessed in our study are free of charge (visits to family physicians and hospitalization) or covered by a small copayment (visit to consultants). Medications are purchased at a subsidized price, which is adjusted for low SES and the number of medications. This health system thus narrows financial gaps for chronic patients. This could explain why SES was not found to be associated with the outcomes of our study.

In our databases, the validity of diagnosis of concordant diseases is high due to their inclusion in the Quality Measures program. Data related to discordant diseases may be less accurate, and could be under-reported. In our study, we grouped the chronic diseases in the list into systems. We tried to be most accurate in our grouping; however, some mis-grouping may have occurred. Malignant diseases were considered discordant diseases and may have contributed to the high rate of mortality. We chose not to exclude persons with malignant diseases, as in previous studies9,12,29,30, since this would necessitate excluding persons with other comorbidities as well. Furthermore, not all malignant diseases are terminal, and the presence of a malignant disease should not lead to lesser care for other comorbidities.

Discordant comorbidities have a significant effect on the outcomes of persons with type 2 diabetes both in combination with concordant comorbidities and without them. For further research, we suggest exploring the contribution of various discordant comorbidities, alone and in combination with concordant comorbidities, on the wellbeing and health of patients with type 2 diabetes. For persons with type 2 diabetes, this could lead to comprehensive recommendations for care that would consider both concordant and discordant comorbidities.

Methods

Design

This is a retrospective cohort study.

Participants

The study included all adults aged 30–90 years on January 1, 2007, insured by CHS and residing within the northern district of Israel. Persons were included if they had a blood glucose test suggestive of new-onset type 2 diabetes in the year 2007, defined as a blood glucose level of ≥ 126 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/L) or a hemoglobin A1C of ≥ 6.5% (48 mmol/mol). Data were validated by the absence of a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, or purchase of medications for type 2 diabetes during 2006. Study exclusion criteria were: gestational diabetes, insulin initiation at the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and death recorded in the first year of the study. We excluded persons who died in the first year after inclusion so that the participants had at least one year of diabetes.

Israel operates a national health insurance scheme. Residents select one of four national health service providers, and an affiliated personal family physician31. CHS provides primary care to 70% of the inhabitants in the northern region of Israel. Primary care is provided in clinics by family physicians and consultants. Primary care clinics and health centers are dispersed throughout the captured area and accessible within a 30-min drive. Visits to family physicians are free of charge. Visits to consultants carry a low copayment. Admissions to hospitals are free of charge.

Persons were monitored until death or the end of the study period, December 31, 2017.

Source of data

CHS operates an integrated electronic medical and administrative file, based on the International Classification of Diseases (9th Revision) combined with ICPC coding. All visits to doctors, either in the community or in hospitals, as well as hospitalizations, are recorded in the CHS database. Chronic conditions recorded in the CHS central register are based on reports by family physicians and community-based specialists, and hospital discharge letters. Chronic diseases that take part in the Quality Measures program, such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are also cross-validated against medication possession records and laboratory data through an automated disease-specific process27,32. We grouped diseases into bodily systems for analysis (Supplementary Table S1 online).

Dates of death (but not causes) are updated through direct linkage to the Israel Ministry of Internal Affairs, using a unique national personal identification number.

Baseline sociodemographic data included age at onset of diabetes, gender and ethnicity (Jewish or Arabs). The only available measure indicating life style behavior was smoking. The cohort was classified into three age groups: 30–45, 45–65 and 65 years and older. Eligibility for exemption from national health insurance payments is given to persons with very low income or who are unemployed for a long period, and was considered an indicator of low SES, as in previous studies33,34.

Type 2 diabetes and comorbidities were documented by the date of recording. We classified comorbid diseases using the system suggested by Piett and Kerr and developed by Mangan et al.8,10 (see Supplementary Table 2). Accordingly, concordant diseases share similar pathophysiology with type 2 diabetes and discordant diseases comprise the remaining pathologies. This classification was used in studies that evaluated quality of care, cost of care and self-care of type 2 diabetes10,18,29,30. Data on utilization of health services in the community, including visits to family physicians and consultants, were retrieved for all persons included in the cohort.

Main measures

Persons were monitored for 11 years from the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, stratified into groups according to whether comorbidities were concordant, discordant, combined (concordant and discordant) or absent. The use of health services and mortality were compared between the groups according to sociodemographic variables, the type of comorbidity and the number of comorbidities.

Statistics

The data were analyzed using SAS version 9.4; p < 0.05 was considered significant. Categorical data were reported as numbers (%) and compared using the chi-square test. Multinomial logistic regression analysis was used to assess the risk of comorbidities of type 2 diabetes. A Cox regression model was used to identify factors that predict mortality. Continuous variables were reported as mean ± SD. Between-group comparisons regarding health services were performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test for non-parametric data.

Ethical approval was obtained from the CHS institutional ethics review board, with exemption from informed consent in data-based research using anonymous information (0137-17-COM2).

Statement: All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines.

References

Chronic diseases and health promotion. WHO. https://www.who.int/chp/about/integrated_cd/en/.

Shaw, J. E., Sicree, R. A. & Zimmet, P. Z. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 87, 4–14 (2010).

Agborsangaya, C. B., Lau, D., Lahtinen, M., Cooke, T. & Johnson, J. A. Multimorbidity prevalence and patterns across socioeconomic determinants: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 12, 201 (2012).

Alonso-Morán, E. et al. Multimorbidity in persons with type 2 diabetes in the Basque Country (Spain): Prevalence, comorbidity clusters and comparison with other chronic patients. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 26, 197–202 (2015).

Dall, T. M. et al. The economic burden of elevated blood glucose levels in 2012: Diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes, gestational diabetes mellitus, and prediabetes. Diabetes Care 37, 3172–3179 (2014).

Luijks, H. et al. Prevalence and incidence density rates of chronic comorbidity in type 2 diabetes patients: An exploratory cohort study. BMC Med. 29, 128 (2012).

American Diabetes Association. Comprehensive medical evaluation and assessment of comorbidities: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care 42, S34–S45 (2019).

Piette, J. D. & Kerr, E. A. The impact of comorbid chronic conditions on diabetes care. Diabetes Care 29, 725–731 (2006).

Gruneir, A. et al. Comorbidity burden and health services use in community-living older adults with diabetes mellitus: A retrospective cohort study. Can. J. Diabetes 40, 35–42 (2016).

Magnan, E. M. et al. The impact of a patient’s concordant and discordant chronic conditions on diabetes care quality measures. J. Diabetes Complicat. 29, 288–294 (2015).

Xu, X., Mishra, G. D. & Jones, M. Evidence on multimorbidity from definition to intervention: An overview of systematic reviews. Ageing Res. Rev. 37, 53–68 (2017).

Struijs, J. N., Baan, C. A., Schellevis, F. G., Westert, G. P. & van den Bos, G. A. Comorbidity in patients with diabetes mellitus: Impact on medical health care utilization. BMC Health Serv. Res. 6, 84 (2006).

Pouplier, S. et al. The development of multimorbidity during 16 years after diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. J. Comorb. 8, 2235042X18801658 (2018).

Samson, S. L. & Garber, A. J. Metabolic syndrome. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 43, 1–23 (2014).

Berkowitz, S. A., Meigs, J. B. & Wexler, D. J. Age at type 2 diabetes onset and glycaemic control: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005–2010. Diabetologia 56, 2593–2600 (2013).

Kalter-Leibovich, O. et al. Adult-onset diabetes among Arabs and Jews in Israel: A population-based study. Diabet. Med. 29, 748–754 (2012).

Jaffe, A. et al. Adult Arabs have higher risk for diabetes mellitus than Jews in Israel. PLoS One 12, e0176661 (2017).

Lin, P. J., Pope, E. & Zhou, F. L. Comorbidity type and health care costs in type 2 diabetes: A retrospective claims database analysis. Diabetes Ther. 9, 1907–1918 (2018).

Janssen, L. M. M. et al. Burden of disease of type 2 diabetes mellitus: Cost of illness and quality of life estimated using the Maastricht Study. Diabet Med. 10, 14285 (2020).

Wojciechowska, J., Krajewski, W., Bolanowski, M., Kręcicki, T. & Zatoński, T. Diabetes and cancer: A review of current knowledge. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 124, 263–275 (2016).

Giovannucci, E. et al. Diabetes and cancer: A consensus report. Diabetes Care 33, 1674–1685 (2010).

Na’amnih, W., Muhsen, K., Tarabeia, J., Saabneh, A. & Green, M. S. Trends in the gap in life expectancy between Arabs and Jews in Israel between 1975 and 2004. Int. J. Epidemiol. 39, 1324–1332 (2010).

Muhsen, K., Green, M. S., Soskolne, V. & Neumark, Y. Inequalities in non-communicable diseases between the major population groups in Israel: Achievements and challenges. Lancet 389, 2531–2541 (2017).

Gregg, E. W. et al. Trends in cause-specific mortality among adults with and without diagnosed diabetes in the USA: An epidemiological analysis of linked national survey and vital statistics data. Lancet 391, 2430–2440 (2018).

Jansson, S. P., Andersson, D. K. & Svärdsudd, K. Mortality trends in subjects with and without diabetes during 33 years of follow-up. Diabetes Care 33, 551–556 (2010).

Tancredi, M. et al. Excess mortality among persons with type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 1720–1732 (2015).

Rennert, G. & Peterburg, Y. Prevalence of selected chronic diseases in Israel. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 3, 404–408 (2001).

The quality indicators program in Clalit Health Services: The first decade. [Hebrew] Harefuah. 149, 204–209, 265 (2010).

Kerr, E. A. et al. Beyond comorbidity counts: How do comorbidity type and severity influence diabetes patients’ treatment priorities and self-management?. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 22, 1635–1640 (2007).

Magnan, E. M. et al. Establishing chronic condition concordance and discordance with diabetes: A Delphi study. BMC Fam. Pract. 28, 42 (2015).

Cohen, R. & Rabin, G. National Insurance Institute R and PA. Membership in sick funds 2016 [Hebrew]. Period Surv. 289, 4 (2017).

Vinker, S., Fogelman, Y., Elhayany, A., Nakar, S. & Kahan, E. Usefulness of electronic databases for the detection of unrecognized diabetic patients. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2, 13 (2003).

Porath, A., Rabinowitz, G., Segal, A. R., & Weitzman, R. Quality indicators for community health care in Israel. Report, The Israel Institute for Health Policy and Health Services Research. (2005).

Shadmi, E., Balicer, R. D., Kinder, K., Abrams, C. & Weiner, J. P. Assessing socioeconomic health care utilization inequity in Israel: Impact of alternative approaches to morbidity adjustment. BMC Public Health 11(1), 1–8 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr Mark Oisgold from Clalit Health Services, Northern Region, for the data mining and Mrs Shiraz Vered from Haifa University for the statistical analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.E.T. contributed to the conception and design of the research. S.E.T. also contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the outcomes, and drafted the manuscript up to its final approval. A.M. contributed to the conception and design of the research and analysis of the outcomes. She gave final approval of the manuscript. L.N.G. contributed to the conception and design of the research. L.N.G. also contributed for the analysis and interpretation of the outcomes. L.N.G. contributed to the writing of the manuscript and gave final approval.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Eilat-Tsanani, S., Margalit, A. & Golan, L.N. Occurrence of comorbidities in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes patients and their impact after 11 years’ follow-up. Sci Rep 11, 11071 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-90379-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-90379-0

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Recent advances in the use of extracellular vesicles from adipose-derived stem cells for regenerative medical therapeutics

Journal of Nanobiotechnology (2024)

-

Determinants of health-related quality of life of patients with type 2 diabetes and multimorbidity: a cross-sectional study

Hormones (2024)

-

Stratification of diabetes in the context of comorbidities, using representation learning and topological data analysis

Scientific Reports (2023)