Abstract

Background

Acceptance of healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP) as an entity and the associated risk of infection by potentially multidrug-resistant (MDR) organisms such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter have been debated. We therefore compared patients with HCAP, hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP), and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) enrolled in a trial comparing linezolid with vancomycin for treatment of pneumonia.

Methods

The analysis included all patients who received study drug. HCAP was defined as pneumonia occurring < 48 hours into hospitalization and acquired in a long-term care, subacute, or intermediate health care facility; following recent hospitalization; or after chronic dialysis.

Results

Data from 1184 patients (HCAP = 199, HAP = 379, VAP = 606) were analyzed. Compared with HAP and VAP patients, those with HCAP were older, had slightly higher severity scores, and were more likely to have comorbidities. Pseudomonas aeruginosa was the most common gram-negative organism isolated in all pneumonia classes [HCAP, 22/199 (11.1%); HAP, 28/379 (7.4%); VAP, 57/606 (9.4%); p = 0.311]. Acinetobacter spp. were also found with similar frequencies across pneumonia groups. To address potential enrollment bias toward patients with MRSA pneumonia, we grouped patients by presence or absence of MRSA and found little difference in frequencies of Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter.

Conclusions

In this population of pneumonia patients, the frequencies of MDR gram-negative pathogens were similar among patients with HCAP, HAP, or VAP. Our data support inclusion of HCAP within nosocomial pneumonia guidelines and the recommendation that empiric antibiotic regimens for HCAP should be similar to those for HAP and VAP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In 2005, the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) jointly published guidelines for treatment of nosocomial pneumonia [1]. In addition to patients whose infections met widely used definitions for hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), these guidelines identified an additional cohort of patients at risk for potentially multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens, those with healthcare-associated pneumonias (HCAP). Criteria for HCAP include pneumonia associated with recent hospitalization in an acute care hospital; residence in a nursing home or extended care facility; or receipt of chronic dialysis, home infusion therapy (including antibiotics), or home wound care. The guidelines suggest that HCAP should be included in the spectrum of HAP and VAP and that patients with HCAP be treated empirically for MDR pathogens [1].

Support for the recommendation that patients with HCAP should receive initial treatment active against MDR pathogens has come predominantly from United States–based studies that documented a high incidence of these pathogens among patients with HCAP [2–8]. Recently, reports from several other countries have also noted increased rates of MDR pathogens in hospitalized patients with HCAP [9–17]. In contrast to these reports, some investigators examining populations of patients hospitalized for HCAP outside of the United States have reported microbiologic patterns more closely resembling those of community acquired pneumonia rather than HAP and VAP [18–21]. This has led some to challenge the use of the HCAP classification itself as well as any associated treatment guidelines [22, 23]. Alternatively, the microbiology associated with these infections, and thus the utility of the HCAP category, may vary with geography or healthcare delivery systems.

Given this controversy and the importance of determining the appropriate initial therapy in these seriously ill patients, we analyzed data from a large, international, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial of patients with nosocomial pneumonia and HCAP [24] to compare baseline patient characteristics and microbiology findings (including the relative incidence of infections with potentially MDR pathogens) among patients with HCAP, HAP, or VAP.

Methods

Study design

This was a retrospective analysis of data from an international, randomized, double-blind, multicenter trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00084266) that compared the efficacy and safety of linezolid and vancomycin for the treatment of patients with nosocomial pneumonia and HCAP due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The details of this trial have been previously reported [24]. Briefly, from October 2004 through January 2010 the study enrolled hospitalized patients aged ≥ 18 years with radiographic and clinical signs of pneumonia consistent with either nosocomial pneumonia or HCAP. The study was approved by an Institutional Review Board or Ethics Committee at each investigational site. The list of investigators and the corresponding Ethics Committees or Institutional Review Boards for this study can be found in an Additional file 1: Figure S1. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their legally authorized representative [24]. The intent-to-treat (ITT) population, which included all randomized patients who received ≥ 1 dose of study drug, was used in this analysis. The population analyzed in this study included patients who were later found not to have MRSA infection and who were excluded from the principal analysis in the report of trial results. Of the 156 enrolling centers, 90 were in the United States.

Pneumonia definitions

Pneumonia was diagnosed by the combination of clinical signs and symptoms, along with a new or evolving infiltrate evident on chest imaging [24]. VAP was defined as onset of pneumonia after > 48 hours of mechanical ventilation, which was calculated by the sponsor from the data available in the case report form. Nosocomial pneumonia cases occurring after at least 48 hours of hospitalization that did not qualify as VAP were classified as HAP. Initially, the study only enrolled patients with pneumonias meeting these criteria. After publication of the ATS/IDSA guidelines in 2005, the study was amended to permit enrollment of patients with HCAP that did not qualify as VAP or HAP. For the trial, a slightly restrictive definition of HCAP was employed: pneumonia acquired in a long-term care or subacute/intermediate healthcare facility (e.g. nursing home, rehabilitation center); pneumonia following recent hospitalization (discharged within 90 days of current admission and previously hospitalized for ≥ 48 hours); or pneumonia in patient who received chronic dialysis care within 30 days prior to study enrollment. This trial did not enroll patients with pneumonia who only met the ATS/IDSA criteria for HCAP by virtue of having recently received home infusion therapy or wound care or of having a family member with an MDR pathogen.

Assessments

Baseline demographic and clinical data were collected including age, sex, race, and comorbidities. Patients were required to have a baseline respiratory or sputum specimen prior to study enrollment or within 24 hours after first dose of study medication. Microbiologic cultures were performed according to the standard of care at the study site, except for patients with chronic ventilation (> 30 days) or tracheostomy, for whom invasive quantitative cultures were mandated. Patients were followed up to 30 days from the date of study enrollment. In keeping with ATS/IDSA guidelines, we considered MRSA, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter spp. to be potentially MDR pathogens.

Statistical analysis

All statistical tests were two-sided. To assess statistical differences in the distribution of baseline characteristics between pneumonia groups, one-way analysis of variance was used for continuous variables, and chi-square test was used for categorical variables. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical procedures were conducted using SAS, version 8.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

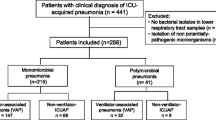

The ITT population included 1184 adult patients, of whom 199 presented with HCAP, 379 with HAP, and 606 with VAP. Compared with those with HAP and VAP, patients with HCAP were older and more likely to have diabetes and cardiac, pulmonary, or renal comorbidities (Table 1). HCAP patients also had slightly higher baseline Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II scores at the time of diagnosis of pneumonia. Investigators from the United States enrolled 60.2% of all patients in the trial and 87.4% of patients diagnosed with HCAP.

The distribution of pathogens by pneumonia group is reported in Table 2. The majority of identified organisms were gram-positive, a finding consistent among HCAP, HAP, and VAP patients. Most of these were MRSA [HCAP, 82/199 (41.2%); HAP, 125/379 (33.0%); VAP, 259/606 (42.7%); p = 0.008 for difference between groups]. Gram-negative organisms were cultured from approximately one-third of patients, with P. aeruginosa being the most common gram-negative organism in all three pneumonia classes [HCAP, 22/199 (11.1%); HAP, 28/379 (7.4%); VAP, 57/606 (9.4%); p = 0.311]. The other potentially MDR gram-negative species, Acinetobacter, was somewhat less common but presented with similar frequencies across pneumonia groups [HCAP, 8/199 (4.0%); HAP, 16/379 (4.2%); VAP, 44/606 (7.3%); p = 0.071]. Most patients had more than one potential pneumonia pathogen cultured, a finding that did not vary with pneumonia type. Among the 689 patients with more than one potential pneumonia pathogen identified, 57.2% had more than one gram-positive species, 5.1% had more than one gram-negative species, and 37.3% had both gram-positive and gram-negative species on culture. Bacteremia rates were similar among pneumonia groups and comparable to rates reported in other series [25, 26].

Because the primary focus of the clinical trial was a comparison of therapies for MRSA pneumonia, recruitment efforts may have been directed toward patients thought to be at increased risk for MRSA infection. As a result, the enrolled population may not be representative of the complete HCAP, HAP, and VAP populations where the study was conducted. To address this potential bias, we divided enrolled patients by pneumonia classification and presence or absence of MRSA, comparing the frequencies of P. aeruginosa and Acinetobacter among the groups (Table 3). Assuming the true population frequencies of P. aeruginosa and Acinetobacter lie between those observed in the MRSA-infected and non-infected groups, there is little difference by pneumonia classification.

The all-cause mortality at day 28 was similar among groups [HCAP, 25/199 (12.6%); HAP, 35/379 (9.2%); VAP, 83/606 (13.7%); p = 0.11].

Discussion

We found that in a population of patients with nosocomial pneumonia enrolled in a large, international, randomized, double-blind trial of therapies for MRSA, the frequencies of potentially MDR gram-negative pathogens were similar among patients with pneumonia classified as HCAP, HAP, or VAP. This suggests that, as recommended in ATS/IDSA guidelines [1] empiric antibiotic regimens utilized for patients hospitalized with HCAP should be similar to those for HAP and VAP.

It is widely accepted that pneumonia occurring after initiation of mechanical ventilation should initially be treated with antibiotics active against MDR pathogens. The rationale is straightforward: ventilated patients are cared for in settings with high antibiotic utilization and often receive antibiotics for other reasons. Both factors contribute to the selection of MDR pathogens when pneumonia occurs. Epidemiologic data in turn provide empiric support for these recommendations [27, 28]. Though these rationales and supporting epidemiologic data are somewhat less compelling for pneumonias acquired in the hospital under circumstances other than mechanical ventilation, the extrapolation of VAP regimens to HAP patients has been widely recommended [1, 29, 30] and generally accepted.

In contrast, recommendations to use antibiotic combinations originally chosen for VAP for patients with HCAP have met with more controversy [19], with some arguing that the HCAP classification itself lacks utility [22]. Our findings speak to both questions. Patients with HCAP were similar to those with HAP and VAP in several key respects: severity of illness; microbiology, particularly the frequency of potentially MDR pathogens; incidence of bacteremia; and short-term mortality. On the other hand, the higher burden of chronic conditions observed among HCAP patients in this study may justify its being a separate classification, particularly for investigators examining factors other than pathogen distribution.

Our study has several limitations. Most importantly, rather than a survey of incident pneumonias, our data derive from a population recruited because of its perceived MRSA risk. Investigators may have taken into consideration factors not accounted for in the collected data that differentiate enrolled patients from other patients with VAP, HAP, and HCAP; e.g. airway specimen gram stain results, history of MRSA colonization, and even infections and colonization of nearby patients. If study investigators intended to enroll patients with MRSA infection, they indeed succeeded, selecting a population with a prevalence of MRSA exceeding that commonly reported [2, 31–33]. We feel data from this study therefore should not be used to compare MRSA risk among pneumonia groups. Rather, our analysis focuses on the prevalence of potentially MDR gram-negative organisms, potential pathogens that the study was not seeking, and the agents under study do not treat. Distributions of potentially MDR gram-negative organisms were similar among patients with VAP, HAP, or HCAP and varied little with the presence or absence of MRSA.

That the study design should enhance recruitment of patients with gram-negative pathogens is certainly not obvious. Patients without MRSA were not permitted to complete the clinical trial, and investigator knowledge of certain specific gram-negative risk factors (gram stain results, colonization history, or local ecology) would likely discourage enrollment of patients with gram-negative infections. On the other hand, to the extent that investigators believed that risk factors for MRSA and MDR gram-negative pathogens are similar, efforts to enhance MRSA pneumonia recruitment might also have increased the prevalence of gram-negative pathogens in our sample. In either case, we have little reason to expect that such biases differed by pneumonia class. Our key finding thus seems robust: the likelihood of MDR gram-negative pathogens being present in HCAP is similar to that in HAP and VAP, pneumonias for which coverage of these organisms is widely accepted.

As is always the case in studies that do not obtain tissue to confirm the presence of pneumonia histopathologically, diagnoses and causative microbiology cannot be established with certainty [34]. It is possible that in many cases potentially pathogenic bacteria were merely colonizers, particularly when multiple potential pathogens were found in the same patient. We know of no reason why this would be more likely in HCAP than in HAP or VAP. To the contrary, we suspect colonization is a more frequent phenomenon among patients with VAP, whose airways are instrumented. In any case, distinguishing true pathogens from colonizers in clinical practice is challenging; a commonly adopted strategy is therefore to treat all isolated organisms reasonably likely to be pathogens. Empiric regimens for HCAP should therefore be as broad in spectrum as those for HAP and VAP.

Geography may play an important role in our findings. HCAP patients were enrolled disproportionately in the United States. Possible interpretations include physicians outside the United States not recognizing patients with HCAP as being at risk for MRSA and so not considering them for enrollment; HCAP being more common in the United States than elsewhere; or investigator access to patients with HCAP varying by country. It seems clear that empiric antibiotics for HCAP in the United States should cover MDR pathogens. Given the possible differences in HCAP incidence across geographic regions, we would be hesitant to assume that the microbiology, and hence recommended treatments, should not also vary with location.

Conclusions

In summary, we compared important demographic characteristics and associated pathogens among patients with HCAP, HAP, or VAP recruited into a large, international pneumonia study. HCAP patients were older and had more comorbidities, higher APACHE II scores, and comparable short-term mortality compared with patients with HAP or VAP. The prevalence of potentially MDR organisms, particularly gram-negatives, was similar across groups, lending support to the recommendation that initial empiric antibiotic therapy should be similar in all groups and should include agents with activity against these pathogens.

Abbreviations

- APACHE:

-

Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation

- ATS:

-

American Thoracic Society

- HAP:

-

Hospital-acquired pneumonia

- HCAP:

-

Healthcare-associated pneumonia

- IDSA:

-

Infectious Diseases Society of America

- ITT:

-

Intent to treat

- MDR:

-

Multidrug-resistant

- MRSA:

-

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- MSSA:

-

Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus

- VAP:

-

Ventilator-associated pneumonia.

References

American Thoracic Society: Infectious Diseases Society of America: guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005, 171 (4): 388-416.

Kollef MH, Shorr A, Tabak YP, Gupta V, Liu LZ, Johannes RS: Epidemiology and outcomes of health-care-associated pneumonia: results from a large US database of culture-positive pneumonia.[Erratum appears in Chest. 2006 Mar;129(3):831]. Chest. 2005, 128 (6): 3854-3862. 10.1378/chest.128.6.3854.

Micek ST, Kollef KE, Reichley RM, Roubinian N, Kollef MH: Health care-associated pneumonia and community-acquired pneumonia: a single-center experience. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007, 51 (10): 3568-3573. 10.1128/AAC.00851-07.

Shorr AF, Zilberberg MD, Micek ST, Kollef MH: Prediction of infection due to antibiotic-resistant bacteria by select risk factors for health care-associated pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2008, 168 (20): 2205-2210. 10.1001/archinte.168.20.2205.

Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF, Micek ST, Mody SH, Kollef MH: Antimicrobial therapy escalation and hospital mortality among patients with health-care-associated pneumonia: a single-center experience. Chest. 2008, 134 (5): 963-968. 10.1378/chest.08-0842.

Madaras-Kelly KJ, Remington RE, Fan VS, Sloan KL: Predicting antibiotic resistance to community-acquired pneumonia antibiotics in culture-positive patients with healthcare-associated pneumonia. J Hosp Med. 2012, 7 (3): 195-202. 10.1002/jhm.942.

Attridge RT, Frei CR, Restrepo MI, Lawson KA, Ryan L, Pugh MJV, Anzueto A, Mortensen EM: Guideline-concordant therapy and outcomes in healthcare-associated pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2011, 38 (4): 878-887. 10.1183/09031936.00141110.

Webb BJ, Dangerfield BS, Pasha JS, Agrwal N, Vikram HR: Guideline-concordant antibiotic therapy and clinical outcomes in healthcare-associated pneumonia. Respir Med. 2012, 106 (11): 1606-1612. 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.08.003.

Jung JY, Park MS, Kim YS, Park BH, Kim SK, Chang J, Kang YA: Healthcare-associated pneumonia among hospitalized patients in a Korean tertiary hospital. BMC Infect Dis. 2011, 11: 61-10.1186/1471-2334-11-61.

Seki M, Hashiguchi K, Tanaka A, Kosai K, Kakugawa T, Awaya Y, Kurihara S, Izumikawa K, Kakeya H, Yamamoto Y, et al: Characteristics and disease severity of healthcare-associated pneumonia among patients in a hospital in Kitakyushu, Japan. J Infect Chemother. 2011, 17 (3): 363-369. 10.1007/s10156-010-0127-8.

Sugisaki M, Enomoto T, Shibuya Y, Matsumoto A, Saitoh H, Shingu A, Narato R, Nomura K: Clinical characteristics of healthcare-associated pneumonia in a public hospital in a metropolitan area of Japan. J Infect Chemother: official journal of the Japan Society of Chemotherapy. 2012, 18 (3): 352-360. 10.1007/s10156-011-0344-9.

Giannella M, Pinilla B, Capdevila JA, Martinez Alarcon J, Munoz P, Lopez Alvarez J, Bouza E: Pneumonia treated in the internal medicine department: focus on healthcare-associated pneumonia. Clin Microbiol Infec: the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2012, 18 (8): 786-794. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03757.x.

Shindo Y, Ito R, Kobayashi D, Ando M, Ichikawa M, Shiraki A, Goto Y, Fukui Y, Iwaki M, Okumura J, et al: Risk factors for drug-resistant pathogens in community-acquired and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013, 188 (8): 985-995. 10.1164/rccm.201301-0079OC.

Ma HM, Ip M, Woo J, Hui DS, Lui GC, Lee NL, Chan PK, Rainer TH: Risk factors for drug-resistant bacterial pneumonia in older patients hospitalized with pneumonia in a Chinese population. QJM. 2013, 106 (9): 823-829. 10.1093/qjmed/hct152.

Falcone M, Corrao S, Licata G, Serra P, Venditti M: Clinical impact of broad-spectrum empirical antibiotic therapy in patients with healthcare-associated pneumonia: a multicenter interventional study. Intern Emerg Med. 2012, 7 (6): 523-531. 10.1007/s11739-012-0795-8.

Carrabba M, Zarantonello M, Bonara P, Hu C, Minonzio F, Cortinovis I, Milani S, Fabio G: Severity assessment of healthcare-associated pneumonia and pneumonia in immunosuppression. Eur Respir J. 2012, 40 (5): 1201-1210. 10.1183/09031936.00187811.

Jeong BH, Koh WJ, Yoo H, Um SW, Suh GY, Chung MP, Kim H, Kwon OJ, Jeon K: Performances of prognostic scoring systems in patients with healthcare-associated pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2013, 56 (5): 625-632. 10.1093/cid/cis970.

Carratala J, Mykietiuk A, Fernandez-Sabe N, Suarez C, Dorca J, Verdaguer R, Manresa F, Gudiol F: Health care-associated pneumonia requiring hospital admission: epidemiology, antibiotic therapy, and clinical outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2007, 167 (13): 1393-1399. 10.1001/archinte.167.13.1393.

Chalmers JD, Taylor JK, Singanayagam A, Fleming GB, Akram AR, Mandal P, Choudhury G, Hill AT: Epidemiology, antibiotic therapy, and clinical outcomes in health care-associated pneumonia: a UK cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2011, 53 (2): 107-113. 10.1093/cid/cir274.

Grenier C, Pepin J, Nault V, Howson J, Fournier X, Poirier M-S, Cabana J, Craig C, Beaudoin M, Valiquette L: Impact of guideline-consistent therapy on outcome of patients with healthcare-associated and community-acquired pneumonia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011, 66 (7): 1617-1624. 10.1093/jac/dkr176.

Garcia-Vidal C, Viasus D, Roset A, Adamuz J, Verdaguer R, Dorca J, Gudiol F, Carratala J: Low incidence of multidrug-resistant organisms in patients with healthcare-associated pneumonia requiring hospitalization. Clin Microbiol Infec. 2011, 17 (11): 1659-1665. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03484.x.

Ewig S, Welte T, Chastre J, Torres A: Rethinking the concepts of community-acquired and health-care-associated pneumonia. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010, 10 (4): 279-287. 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70032-3.

Lopez A, Amaro R, Polverino E: Does health care associated pneumonia really exist?. Eur J Intern Med. 2012, 23 (5): 407-411. 10.1016/j.ejim.2012.05.006.

Wunderink RG, Niederman MS, Kollef MH, Shorr AF, Kunkel MJ, Baruch A, McGee WT, Reisman A, Chastre J: Linezolid in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nosocomial pneumonia: a randomized, controlled study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012, 54 (5): 621-629. 10.1093/cid/cir895.

Agbaht K, Diaz E, Munoz E, Lisboa T, Gomez F, Depuydt PO, Blot SI, Rello J: Bacteremia in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia is associated with increased mortality: A study comparing bacteremic vs. nonbacteremic ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 2007, 35 (9): 2064-2070. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000277042.31524.66.

Montravers P, Veber B, Auboyer C, Dupont H, Gauzit R, Korinek AM, Malledant Y, Martin C, Moine P, Pourriat JL: Diagnostic and therapeutic management of nosocomial pneumonia in surgical patients: results of the Eole study. Crit Care Med. 2002, 30 (2): 368-375. 10.1097/00003246-200202000-00017.

Richards MJ, Edwards JR, Culver DH, Gaynes RP: Nosocomial infections in medical intensive care units in the United States. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. Crit Care Med. 1999, 27 (5): 887-892. 10.1097/00003246-199905000-00020.

Chastre J, Fagon J-Y: Ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002, 165 (7): 867-903. 10.1164/ajrccm.165.7.2105078.

Song J-H, Asian Hospital Acquired Pneumonia Working G: Treatment recommendations of hospital-acquired pneumonia in Asian countries: first consensus report by the Asian HAP Working Group. Am J Infect Control. 2008, 36 (4 Suppl): S83-S92.

Torres A, Ewig S, Lode H, Carlet J, European HAPwg: Defining, treating and preventing hospital acquired pneumonia: European perspective. Intensive Care Med. 2009, 35 (1): 9-29. 10.1007/s00134-008-1336-9.

Kett DH, Cano E, Quartin AA, Mangino JE, Zervos MJ, Peyrani P, Cely CM, Ford KD, Scerpella EG, Ramirez JA, et al: Implementation of guidelines for management of possible multidrug-resistant pneumonia in intensive care: an observational, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011, 11 (3): 181-189. 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70314-5.

Koulenti D, Lisboa T, Brun-Buisson C, Krueger W, Macor A, Sole-Violan J, Diaz E, Topeli A, DeWaele J, Carneiro A, et al: Spectrum of practice in the diagnosis of nosocomial pneumonia in patients requiring mechanical ventilation in European intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 2009, 37 (8): 2360-2368. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a037ac.

Venditti M, Falcone M, Corrao S, Licata G, Serra P, Study Group of the Italian Society of Internal M: Outcomes of patients hospitalized with community-acquired, health care-associated, and hospital-acquired pneumonia.[Summary for patients in Ann Intern Med. 2009 Jan 6;150(1):I36; PMID: 19124813]. Ann Intern Med. 2009, 150 (1): 19-26. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-1-200901060-00005.

Kirtland SH, Corley DE, Winterbauer RH, Springmeyer SC, Casey KR, Hampson NB, Dreis DF: The diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a comparison of histologic, microbiologic, and clinical criteria. Chest. 1997, 112 (2): 445-457. 10.1378/chest.112.2.445.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/13/561/prepub

Acknowledgements

Statistics support was provided by Michele Wible of Pfizer Inc. Editorial support was provided by Lisa Baker of UBC Scientific Solutions and was funded by Pfizer Inc.

Preliminary findings from this study were presented as: Kett DH, Quartin AA, Scerpella EG, Huang DB. Demographics, Microbiology and Mortality Associated with Healthcare-Associated (HCAP), Hospital-Acquired (HAP) and Ventilator-Associated (VAP) Pneumonia: A Retrospective Analysis of 1184 patients. Abstract K-1446. Presented at 51st Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (ICAAC); September 17–20, 2011; Chicago, IL, USA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc. AAQ has no disclosures to report. EGS and SP, formerly of Pfizer, were employees and shareholders of Pfizer Inc at the time this manuscript was developed. DHK has received research support, served as a consultant to, and was on the speakers bureau of Pfizer Inc, Astellas, and GlaxoSmithKline.

Authors’ contributions

All authors were responsible for conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript, and final approval of the manuscript. EGS and SP were responsible for obtaining funding, acquisition of data, and obtaining administrative, statistical, and technical support. DHK is guarantor of this paper and takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Quartin, A.A., Scerpella, E.G., Puttagunta, S. et al. A comparison of microbiology and demographics among patients with healthcare-associated, hospital-acquired, and ventilator-associated pneumonia: a retrospective analysis of 1184 patients from a large, international study. BMC Infect Dis 13, 561 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-13-561

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-13-561