Abstract

Ostreid herpesvirus 1 (OsHV-1) is a DNA virus belonging to the Malacoherpesviridae family from the Herpesvirales order. OsHV-1 has been associated with mortality outbreaks in different bivalve species including the Pacific cupped oyster, Crassostrea gigas. Since 2008, massive mortality events have been reported among C. gigas in Europe in relation to the detection of a variant of OsHV-1, called μVar. Since 2009, this variant has been mainly detected in France. These results raise questions about the emergence and the virulence of this variant. The search for association between specific virus genetic markers and clinical symptoms is of great interest and the characterization of the genetic variability of OsHV-1 specimens is an area of growing interest. Determination of nucleotide sequences of PCR-amplified virus DNA fragments has already been used to characterize OsHV-1 specimens and virus variants have thus been described. However, the virus DNA sequencing approach is time-consuming in the high-scale format. Identification and genotyping of highly polymorphic microsatellite loci appear as a suitable approach. The main objective of the present study was the development of a genotyping method in order to characterise clinical OsHV-1 specimens by targeting a particular microsatellite locus located in the ORF4 area. Genotyping results were compared to sequences already available. An excellent correlation was found between the detected genotypes and the corresponding sequences showing that the genotyping approach allowed an accuraté discrimination between virus specimens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ostreid herpesvirus 1 (OsHV-1) is a DNA virus belonging to the Malacoherpesviridae family from the Herpesvirales order [1]. The virus has been purified from naturally infected Crassostrea gigas larvae [2] and its genome entirely sequenced [3]. The viral genome is a large linear duplex DNA molecule of 207 kb (GenBank accession number AY509253) that encodes at least 124 genes [3].

OsHV-1 has been associated with mortality outbreaks in different bivalve species including the Pacific cupped oyster, C. gigas[4, 5]. Since 2008, massive mortality outbreaks have been reported among C. gigas spat in several farming areas in Europe [6–11] in relation to the detection of a newly described OsHV-1 variant called μVar [7]. Although the reference type (a viral specimen collected in France in 1995 during a mortality event affecting C. gigas larvae, GenBank accession number AY509253) and the variant μVar were detected in association with mortality outbreaks in 2008 in France, virus detection since 2009 has mainly concerned the μVar variant [7, 10, 12]. These results raise questions about the emergence and the virulence of the μVar variant. In this context, tools are needed in order to better describe OsHV-1 diversity in relation to virulence and geographical distribution. In light of the genetic diversity of OsHV-1, the search for associations between specific virus genetic markers and clinical symptoms is of great interest.

Determination of nucleotide sequences of PCR-amplified virus DNA fragments is the most accurate method for virus genotyping [13]. The DNA sequencing approach has been used to characterise OsHV-1 specimens and virus variants were thus reported [7, 10, 12, 14–19]. The μVar variant [7] showed several differences in two genome areas when compared with the reference type (GenBank accession n° AY509523) and all these differences need to be observed to define a viral specimen as the μVar variant.

Virus DNA sequencing is, however, time-consuming in the high-scale format. The identification and genotyping of highly polymorphic microsatellite areas from vertebrate herpesviruses appears as a suitable approach. Microsatellites have been reported from different herpesviruses including human cytomegalovirus and they have been used as molecular markers to define virus polymorphism [20–24].

Since the μVar variant demonstrated a deletion of 12 bp in a microsatellite locus located up-stream of the ORF4 [7], the main objective of the present study was the development of a genotyping method. This method was used to characterise 47 clinical OsHV-1 specimens by targeting this microsatellite locus. DNA sequences already available were used to compare results obtained with both techniques. Sequencing and genotyping appeared to be equally useful to differentiate clinical OsHV-1 specimens.

Materials and methods

Oyster samples and C2/C6 sequences

Forty-seven samples of the Pacific cupped oyster, C. gigas, were selected in the present study in order to analyze them by genotyping. These included animals collected from 1993 to 2010 and covered different stages of development (larvae, spat and adults) (Table 1). Most of the samples (45) were collected in France during mortality outbreaks recorded by the national network for mollusc disease monitoring (Repamo, Ifremer) and were stored frozen at −20 °C. Two samples were of different geographical origins (Japan and USA) (Table 1).

Total nucleic acids were previously extracted from oyster samples using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) [25] and the quantity of viral DNA was estimated by real time PCR using the primer pair C9/C10 [26] for the purpose of a previous study [10]. Sequences of C2/C6 [27] PCR products from the sample set were previously defined in the laboratory [10] and deposited in GenBank (Table 1).

Genotyping of a microsatellite locus

A microsatellite locus (called H10) was identified up-stream of ORF4 based on an analysis of the whole genome of OsHV-1 (GenBank accession n° AY509523) using the MsatFinder algorithm [28] and selected for genotyping. The number of repeat units of this trinucleotide microsatellite was 8 in the reference sequence (GenBank accession n° AY509523). This microsatellite (H10) was located in inverted repeated regions (4440–4463 positions and 178547–178547 positions). A primer pair (H10F/H10R) was designed with primer3 [29] (H10F: gtgatggctttggtcaaggt and H10R: ggcgcgatttgtcagtttag). The expected size of the PCR product was 151 bp.

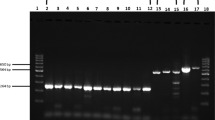

PCR was performed in 20 μL reaction volumes in a thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, Villebon-sur-Yvette, France). Each reaction contained 11.76 μL dH2O, 4.0 μL buffer 5X (Promega, Charbonnières-les-Bains, France), 0.8 μL MgCl2 (25 mM), 2 μL dNTP (2 mM), 0.18 μL of each primer (20 μM), and 0.08 μL GoTaq®DNA polymerase (5U/μL, Promega). PCR cycling conditions were 96 °C for 5 min; then 30 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 57 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 30 s; and finally a step of 72 °C for 2 min. PCR products were verified by electrophoresis (1% agarose gel).

PCR products were mixed with formamide and GeneScan 500-ROX size standard (Applied Biosystems) respectively according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (1.5 μL PCR products, 0.25 μL Rox size standard and 13.25 μL formamide). After 5 min denaturation followed by rapid cooling, PCR products were detected using an ABI 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems), and the fragment length was estimated through the GeneMapper 3.7 software.

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analysis was performed on C2/C6 [27] sequences [10] using 3 computational approaches. Information concerning genotyping results (length of the fragment) was included in specimen codes. For the first approach, a phylogenetic tree was created from sequence alignments using the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method [30]. The significance of the branching orders was assessed by bootstrap resampling of 1000 replicates. The second approach was based on phylogeny inference according to the Maximum Likelihood method based on the Tamura-Nei model [31]. Bootstrap data sets (1000 replicates) were generated. The Maximum Parsimony method was also used as the third approach. All approaches were implemented using the MEGA5 program [32].

Results

Polymorphism of C2/C6 PCR products

Comparing sequences of C2/C6 PCR products (Table 1) demonstrated a high polymorphism with 82 positions of a 482 nucleotide sequence (17%) showing a substitution/deletion/insertion defining 9 virus specimen types from the analysed samples (data not shown). H10F/H10R sequences revealed only a variability in the number of repeat units at the targeted short tandem repeat (H10) defining 7 virus specimen types from the analysed samples (Figure 1). An additional type corresponded to acute viral necrosis virus (AVNV) infecting cultured scallops, Chlamys farreri, in China [33] (Figure 1). The minimum and maximum numbers of repeat units of the trinucleotide motif were 3 (AVNV) and 13 (2006/18/France), respectively (Figure 1).

H10F/H10R sequence alignments between virus specimens. Partial C2-C6 (H10F/H10R) sequence alignments between virus specimens demonstrating variability at the microsatellite locus (H10) and mutation points. Locations of H10F/H10R primers are identified as surligned. OsHV-1 reference type, the variant μVar and AVNV sequences are highlited in grey. Stars represent identity at a particular nucleotide position.

Microsatellite genotyping

The 47 samples were genotyped for the H10 microsatellite locus which is located up-stream of the ORF4. In this region, a 13 bp deletion is one of the characteristics of the μVar variant [7] and was hence chosen to achieve its interest as a diagnostic tool. Protocol optimisation focussed on the concentration of the labelled primers and the DNA in the PCR mix, but also the annealing temperature, time of elongation, and finally the dilution factor of the PCR products in the formamide before fragment length analysis in the Genetic Analyzer.

Fragments were successfully amplified for the 47 samples (Figure 2). Seven different genotypes were detected corresponding to different fragment lengths estimated through the GeneMapper 3.7 software (135, 152, 155, 159, 161, 165 and 168 bp; Figure 2 and Table 2). Two genotypes (135 and 152) were more frequent with 20 and 16 of the samples, respectively (Table 2). Five more genotypes were detected in 11 samples (Table 2). When comparing the detected genotypes and the corresponding H10F/H10R sequences (Table 2), a good correlation was reported (Figure 3) showing that the genotypes identified by genotyping of the microsatellite reflected the sequences and allowed a clear discrimination between them. Moreover, sequencing showed that specimens presenting a fragment length estimated at 135 bp and 152 bp corresponded to the reference type and the μVar variant, respectively. Although all the samples collected in France in 1993, 1994 and 1995 demonstrated a fragment length estimated at 152 bp, French samples collected in 2009 and 2010 showed a single pattern at 135 bp. (Table 2). Different genotypes were detected each year for samples collected in France from 2005 to 2008 (Table 2).

Electrophoregrams from virus specimens. The two traces represent separate reactions on 2 DNA extracts (2008–017 and 2008–020). The boxed numbers under the peaks of the traces are the fragment sizes in base pairs assigned by comparison with the standard curve generated with the internal size standard.

Phylogenetic analysis

The phylogenetic trees built from the C2/C6 amplicon sequences (ORF4 and its related up stream area) using 3 different approaches allowed identification of 2 major groups from the 47 analysed virus specimens (Figure 4). A first group contained French specimens collected from 1993 to 2008 including the reference type (OsHV-1, GenBank n° accession AY509253) and the sample collected in the USA (California) in 2007. Although a main genotype (152 bp) was represented in this group, several other genotypes were also observed (155, 159, 162, 165 and 168 bp) (Figure 4). The second large group comprised French specimens collected from 2008 to 2010. It included the sequence of the μVar variant deposited in GenBank (accession n° HQ842610) and the sequence of the sample from Japan (Figure 4). All samples grouped with the μVar variant demonstrated a similar genotype at 135 bp (Figure 4). Two additional groups were defined. Each of them included a single member: a virus specimen collected in France in 1993 on the one hand and AVNV on the other hand.

Phylogenetic tree representing the relationships of virus specimens. Phylogenetic tree representing the relationships of 47 virus specimens (fragment lengths obtained by genotyping were included in specimen codes) and 3 reference sequences (OsHV-1, the variant μVar and AVNV) based on a fragment of the ORF4 and its up-stream zone (460 nts). Fragment lengths were included in specimen codes. The analysis involved 50 nucleotide sequences. Evolutionary analysis was conducted in MEGA5. The tree was generated by the Maximum Likelihood method.

Discussion

This study reports for the first time the use of a microsatellite locus (H10) present in the OsHV-1 genome to analyze the virus diversity using 47 OsHV-1 specimens. Microsatellites are short tandem repeats that occur in eukaryote, prokaryote, and also some virus genomes. They are highly DNA mutable sequences and represent hot spots of length mutation. Replication slippage errors are considered as the main cause of insertions and deletions at microsatellite loci. Microsatellites have thus been extensively used as molecular markers in numerous genetic diversity and genome mapping studies. Short microsatellite polymorphisms have already been used to describe genetic polymorphism of different vertebrate herpesviruses [20–24]. As an example, Deback et al. [24] used the microsatellite technology to determine genetic relationship between HSV-1 strains and showed that each patient was characterized by its own HSV-1 microsatellite haplotype.

The microsatellite selected in the present study (H10) is found in a noncoding region. This microsatellite was selected since numerous sequences are already available for this region demonstrating a high level of length polymorphism [7, 10, 12, 19].

In the present study analysis of C2-C6 sequences [10] was first carried out to identify polymorphisms among the selected OsHV-1 specimens and to prepare genotyping. The ORF4 area with 82 substitutions/deletions/insertions appeared highly polymorphic presenting variability in the number of repeat units at the targeted short tandem repeat and a variety of point mutations defining 9 virus types. Sequence alignment allowed identification of polymorphisms among virus specimens interpreted as being the reference type (GenBank AY509253). Several French samples collected from 1993 to 2008 demonstrated 100% identity with the reference type and as such could be identified as OsHV-1 [3]. Other samples collected in France from 2003 to 2008 showed some differences in comparison with the reference type. Finally, a French virus specimen collected in 1993 presented high homologies with the variant OsHV-1 Var [14, 16, 34]. These results showed that different OsHV-1 variants are represented in the sample set selected for the present study. Acute Viral Necrosis Virus (AVNV) [33] was included in comparing C2-C6 PCR product sequences sinced its complete genome is available in GenBank and it presents the shorter sequence for the H10 microsatellite. The number of sequences from countries other than France used in this study was low. Complementary analysis of additional specimens is ongoing in the laboratory and detailed comparison of sequences would present further epidemiological information on OsHV-1.

Among the 47 samples analysed, 7 different genotypes were detected with 2 more frequent ones. They respectively included specimens interpreted as the reference type and the μVar variant. Five more genotypes were also detected. When comparing the genotypes detected and the corresponding C2/C6 sequences, a good correlation was reported showing that the detected genotypes reflected the sequences and allowed a clear discrimination between specimens. However, the number of virus specimen types (9) obtained by sequencing of C2-C6 PCR products remains higher than the number of genotypes defined by genotyping (7). Although analysis of variation in length through genotyping offers a first order of discrimination, sequencing of alleles and viral length variants adds a second level. Sequencing is a necessary step to obtain maximum resolution between viral specimens also revealing SNP.

The polymorphism reported for the selected microsatellite in the present study confirms the interest of such analysis to describe OsHV-1 genome diversity. Moreover, a multiplex genotyping based on analysis of several microsatellites needs to be developed for OsHV-1. The in silico analysis of the OsHV-1 genome using the MsatFinder algorithm demonstrated the presence of 12 short repeat sites including 4 mononucleotide units, 5 dinucleotide repeats, and 3 trinucleotide repeats (data not shown). Most of the identified microsatellites were localized in noncoding parts of the OsHV-1 genome, except for 3 of them located in ORF 66, 77 and 106, respectively. The number of repeat units of dinucleotide or trinucleotide microsatellites was 5 or 8. The longest mononucleotide sequence was 18 bases and 3 microsatellites were located in inverted repeated regions. As most of OsHV-1 repeats are found in noncoding areas, they can be considered as evolutionarily neutral or nearly so and therefore as suitable markers for epidemiology studies. Such a technique targeting several microsatellite loci may provide a rapid and accurate tool that can be used to compare OsHV-1 specimens and to study the epidemiology of viral infections. Finally, polymorphism of microsatellites may also be used to study viral strain virulence. Perdue et al. [35] reported that the increased virulence of a particular strain of the avian influenzae virus is related to the increase in the length of a microsatellite at the hemagglutinin cleavage site.

In conclusion, genotyping based on microsatellite loci appears as a powerful tool to study OsHV-1 polymorphism and can offer a first level of discrimination between specimens in order to select best candidates for complete genome sequencing. Futhermore comparative diversity studies between the host, Crassostrea gigas, and OsHV-1 can be easily performed using oyster mircosatellite markers [36] and to characterize coevolution in this recently introduced oyster species in Europe [37].

References

Davison AJ, Eberle R, Ehlers B, Hayard GS, McGeoch DJ, Minson AM, Pellett PE, Roizman B, Studdert MJ, Thiry E: The order Herpesvirales. Arch Virol. 2009, 154: 171-177. 10.1007/s00705-008-0278-4.

Le Deuff RM, Renault T: Purification and partial genome characterization of a herpes-like virus infecting the Japanese oyster, Crassostrea gigas. J Gen Virol. 1999, 80: 1317-1322.

Davison AJ, Trus BL, Cheng N, Steven AC, Watson MS, Cunningham C, Le Deuff RM, Renault T: A novel class of herpesvirus with bivalve hosts. J Gen Virol. 2005, 86: 41-53. 10.1099/vir.0.80382-0.

Renault T, Le Deuff RM, Cochennec N, Maffart P: Herpesviruses associated with mortalities among Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas, in France - Comparative study. Rev Med Vet. 1994, 145: 735-742.

Garcia C, Thébault A, Dégremont L, Arzul I, Miossec L, Robert M, Chollet B, François C, Joly JP, Ferrand S, Kerdudou N, Renault T: OsHV-1 detection and relationship with C. gigas spat mortality in France between 1998 and 2006. Vet Res. 2011, 42: 73-84. 10.1186/1297-9716-42-73.

Efsa: Scientific opinion on the increased mortality events in Pacific oysters, Crassostrea gigas. EFSA J. 2010, 8: 1894-1954.

Segarra A, Pépin JF, Arzul I, Morga B, Faury N, Renault T: Detection and description of a particular Ostreid herpesvirus 1 genotype associated with massive mortality outbreaks of Pacific oysters, Crassostrea gigas. Virus Res. 2010, 153: 92-95. 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.07.011.

Lynch SA, Carlson J, Reilly AO, Cotter E, Culloty SC: A previously undescribed ostreid herpes virus 1 (OsHV-1) genotype detected in the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas, in Ireland. Parasitology. 2012, 139: 1526-1532. 10.1017/S0031182012000881.

Peeler JE, Reese RA, Cheslett DL, Geoghegan F, Power A, Trush MA: Investigation of mortality in Pacific oysters associated with Ostreid herpesvirus-1 μVar in the Republic od Ireland in 2009. Prev Vet Med. 2012, 105: 136-143. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2012.02.001.

Renault T, Moreau P, Faury N, Pépin JF, Segarra A, Webb S: Analysis of clinical ostreid herpesvirus 1 (Malacoherpesviridae) specimens by sequencing amplified fragments from three virus genome areas. J Virol. 2012, 86: 5942-5947. 10.1128/JVI.06534-11.

Roque A, Carrasco N, Andree KB, Lacuesta B, Elandaloussi L, Gairin I, Rodgers CJ, Furones MD: First report of OsHV-1 microvar in Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) cultured in Spain. Aquaculture. 2012, 324: 303-306.

Martenot C, Oden E, Travaillé E, Malas JP, Houssin M: Detection of different variants of Ostreid Herpesvirus 1 in the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. Virus Res. 2011, 160: 25-31. 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.04.012.

Norberg P, Bergström T, Liljeqvist JA: Genotyping of clinical Herpes Simplex Virus type 1 isolates by use of restriction enzymes. J Clin Microbiol. 2006, 44: 4511-4514. 10.1128/JCM.00421-06.

Arzul I, Nicolas JL, Davison AJ, Renault T: French scallops: a new host for ostreid herpesvirus 1. Virology. 2001, 290: 342-349. 10.1006/viro.2001.1186.

Arzul I, Renault T, Lipart C, Davison AJ: Evidence for interspecies transmission of oyster herpesvirus in marine bivalves. J Gen Virol. 2001, 82: 865-870.

Renault T, Lipart C, Arzul I: A herpes-like virus infecting Crassostrea gigas and Ruditapes philippinarum larvae in France. J Fish Dis. 2001, 24: 369-376. 10.1046/j.1365-2761.2001.00300.x.

Friedman CS, Estes RM, Stokes NA, Burge CA, Hargove JS, Barber BJ, Elston RA, Burreson EM, Reece KS: Herpes virus in juvenile Pacific oysters Crassostrea gigas from Tomales Bay, California, coincides with summer mortality episodes. Dis Aquat Organ. 2005, 63: 33-41.

Moss JA, Burreson EM, Cordes JF, Dungan CF, Brown GD, Wang A, Wu X, Reece KS: Pathogens in Crassostrea ariakensis and other Asian oyster species: implications for non-native oyster introduction in Chesapeake Bay. Dis Aquat Organ. 2007, 77: 207-233.

Shimahara Y, Kurita J, Kiryu I, Nishioka T, Yuasa K, Kawana M, Kamaishi T, Oseko N: Surveillance of Type 1 Ostreid Herpesvirus (OsHV-1) variants in Japan. Fish Pathol. 2012, 47: 129-136. 10.3147/jsfp.47.129.

Davis CL, Field D, Metzgar D, Saiz R, Morin PA, Smith IL, Spector SA, Wills C: Numerous length polymorphism at short tandem repeats in human cytomegalovirus. J Virol. 1999, 73: 6265-6270.

Walker A, Petheram SJ, Ballard L, Murph JR, Demmler GJ, Bale JF: Characterization of human cytomegalovirus strains by analysis of short tandem repeat polymorphisms. J Clin Microbiol. 2001, 39: 2219-2226. 10.1128/JCM.39.6.2219-2226.2001.

Picone O, Costa JM, Ville Y, Rouzioux C, Leruez-Ville M: Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) short tandem repeats analysis in congenital infection. J Clin Virol. 2005, 32: 254-256. 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.10.012.

Deback C, Boutolleau D, Depienne C, Luyt CE, Bonnafous P, Gautheret-Dejean A, Garrigue I, Agut H: Utilization of microsatellite polymorphism for differentiating herpes simplex virus type 1 strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2008, 47: 533-540.

Deback C, Luyt CE, Lespinats S, Depienne C, Boutolleau D, Chastre J, Agut H: Microsatellite analysis of HSV-1 isolates: from oropharynx reactivation toward lung infection in patients undergoing mechanical vantilation. J Clin Virol. 2010, 47: 313-320. 10.1016/j.jcv.2010.01.019.

Qiagen: QIAmp® DNA Mini and Blood Mini Handbook. 2007, D-46724 Hilden, Germany: QIAGEN Gmbh, 2

Pépin JF, Riou A, Renault T: Rapid and sensitive detection of ostreid herpesvirus A in oysters samples by real-time PCR. J Virol Methods. 2008, 149: 269-276. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2008.01.022.

Renault T, Arzul I: Herpes-like virus infections in hatchery-reared bivalve larvae in Europe: specific viral DNA detection by PCR. J Fish Dis. 2001, 24: 161-167. 10.1046/j.1365-2761.2001.00282.x.

Thurston MI, Field D: Msatfinder: detection and characterisation of microsatellites. [http://www.bioinformatics.org/ftp/pub/msatfinder/README.txt]

Rozen S, Skaletsky H: Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Bioinformatics Methods and Protocols: Methods in Molecular Biology. Edited by: Krawetz S, Misener S. 2000, Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, 365-386.

Saitou N, Nei M: The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987, 4: 406-425.

Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S: MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011, 28: 2731-2739. 10.1093/molbev/msr121.

Tamura KM, Nei M: Estimation of the number substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol Biol Evol. 1993, 10: 512-526.

Ren W, Chen H, Renault T, Cai Y, Bai C, Wang C, Huang J: Complete genome sequence of acute viral necrosis virus associated with massive mortality outbreaks in the Chinese scallop, Chlamys farreri. Virol J. 2013, 10: 110-116. 10.1186/1743-422X-10-110.

Renault T, Lipart C, Arzul I: A herpes-like virus infects a non-ostreid bivalve species: virus replicaton in Ruditapes philippinarum larvae. Dis Aqua Organ. 2001, 45: 1-7.

Perdue ML, Garcia D, Senne D, Fraire M: Virulence-associated sequence duplication at the hemagglutinin cleavage site of avian influenza viruses. Virus Res. 1997, 49: 173-186. 10.1016/S0168-1702(97)01468-8.

Li R, Li Q, Cornette C, Dégremont L, Lapègue S: Development of four EST-SSR multiplex PCRs in the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) and their validation in parentage assignment. Aquaculture. 2010, 310: 234-239. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2010.09.037.

Rohfritsch A, Bierne N, Boudry P, Heurtebise S, Cornette F, Lapègue S: Population genomics shed light on the demographic and adaptive histories of European invasion in the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas. Evol Appl. 2013, 6: 1064-1078.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially funded through the EU project Aquagenet (SOE2/P1/E287).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

This work was supported by Ifremer (Institut Français pour l’Exploitation de la Mer). The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

This study is the result of a collective work. TR and SL conceived this study, and participated in its design. TR, GT and SL carried out the design of the protocol, with the help of the other authors. GT, NF, PM and AS carried out sample analyses. TR and SL drafted the manuscript. VBS participated in the discussion and modification of the manuscript. All authors read, corrected, and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Renault, T., Tchaleu, G., Faury, N. et al. Genotyping of a microsatellite locus to differentiate clinical Ostreid herpesvirus 1 specimens. Vet Res 45, 3 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1297-9716-45-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1297-9716-45-3