Abstract

We evaluate a 5-dimensional Randall Sundrum type metric in the Lagrangian of the Einstein–Chern–Simons gravity, and then we derive an action and its corresponding field equations, for a 4-dimensional brane embedded in the 5-dimensional space-time of the theory, which in the limit \(l\rightarrow 0\) leads to the 4-dimensional general relativity with cosmological constant. An interpretation of the \(h^{a}\) matter field present in the Einstein–Chern–Simons gravity action is given. As an application, we find some Friedmann–Lemaitre–Robertson–Walker cosmological solutions that exhibit accelerated behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The study of the so called brane world models has introduced completely new ways of looking upon standard problems in many areas of theoretical physics. The existence of those new dimensions may have non trivial effects in our understanding of the cosmology of the early Universe, among many other issues.

The idea dates back to the 1920s, to the works of Kaluza and Klein [1, 2] who tried to unify electromagnetism with Einstein gravity by assuming that the photon originates from the fifth component of the metric. By convention, it has always been assumed that such extra dimensions should be compactified to manifolds of small radii with sizes of the order of the Planck length.

It was only in the last years of the twentieth century when people started to ask the question of how large could these extra dimensions be without getting into conflict with observations.

Of particular interest in this context are the Randall and Sundrum models [3, 4] for warped backgrounds, with compact or even infinite extradimensions. Randall and Sundrum proposed that the metric of the space-time is given by

i.e. a 4-dimensional metric multiplied by a “warp factor” which is a rapidly changing function of an additional dimension, where k is a scale of order the Planck scale, \(x^{\mu }\) are coordinates for the familiar four dimensions, while \(0\le \phi \le \pi \) is the coordinate for an extra dimension, which is a finite interval whose size is set by \(r_{c}\), known as “compactification radius”. Randall and Sundrum showed that this metric is a solution to Einstein’s equations.

The Einstein–Chern–Simons gravity [5] is a gauge theory whose Lagrangian density is given by a 5-dimensional Chern–Simons form for the so called \({\mathfrak {B}}\) algebra. This algebra can be obtained from the Anti-de Sitter algebra and a particular semigroup S by means of the S-expansion procedure introduced in Refs. [6, 7]. The field content induced by the \({\mathfrak {B}}\) algebra includes the vielbein \(e^{a}\), the spin connection \(\omega ^{ab}\), and two extra bosonic fields \(h^{a}\) and \(k^{ab}.\) The Einstein–Chern–Simons gravity has the interesting property that the 5-dimensional Chern–Simons Lagrangian for the \({\mathcal {B}}\) algebra, given by [5]

where \(R^{ab}=\mathrm {d}\omega ^{ab}+\omega _{\,c}^{a}\omega ^{cb}\) and \(T^{a}=\mathrm {d}e^{a}+\omega _{\,c}^{a}e^{c}\), leads to the standard general relativity without cosmological constant in the limit where the coupling constant l tends to zero while keeping the Newton’s constant fixed. It should be noted that there is an absence of kinetic terms for the fields \(h^{a}\) and \(k^{ab}\) in the Lagrangian \(L_{ChS}^{(5)}\) [9] (for detail see appendix).

The main purpose of this letter is to make the 5-dimensional Einstein–Chern–Simons theory consistent with the idea of a 4-dimensional space-time, through the replacement of a Randall Sundrum type metric in the Lagrangian (2). It is also a purpose of this paper to get an interpretation of the \(h^{a}\) matter field present in the Einstein–Chern–Simons gravity action.

The article is organized as follows: in Sect. 2, we evaluate a 5-dimensional Randall Sundrum type metric in the Lagrangian (2), and then we derive an action for a 4-dimensional brane embedded in the 5-dimensional space-time of the Einstein–Chern–Simons gravity, which in the limit \(l\rightarrow 0\) leads to the 4-dimensional general relativity with cosmological constant. In Sect. 3, we write the action for the brane in tensorial language and then we find the corresponding Friedmann equations for homogeneous and isotropic cosmology, and we obtain some De Sitter accelerated solutions. Finally, concluding remarks are presented in Sect. 4.

2 Action for a 4-dimensional brane embedded in the 5-dimensional space-time

Chern–Simons theories of gravity are valid only in odd-dimensions and, in order to have a well defined even-dimensional theory, it would be necessary to carry out some kind of dimensional reduction or compactification.

In Refs. [3, 4] a mechanism was introduced that allows to connect the Einstein–Chern–Simons action with an action for a 4-dimensional brane embedded in the 5-dimensional space-time.

In Ref. [5], the 5-dimensional Chern–Simons Lagrangian for gravity (2) was developed. The corresponding action is invariant under the so-called \({\mathfrak {B}}\) algebra, which induces two geometrical fields, the vielbein \(e^{a}\) and the spin connection \(\omega ^{ab}\), and two bosonic matter fields, \(h^{a}\) and \(k^{ab}\). In order to find an action and its corresponding field equations for a 4-dimensional brane embedded in the 5-dimensional space-time \(\Sigma _{5}\) of the Einstein–Chern–Simons gravity, we will consider the following 5-dimensional Randall Sundrum type metric

where \(e^{2f(\phi )}\) is the so-called “warp factor”, and \(r_{c}\) is the so-called “compactification radius” of the extra dimension, which is associated with the coordinate \(0\leqslant \phi <2\pi \). The symbol \(\sim \) denotes 4-dimensional quantities related to the space-time \(\Sigma _{4}.\) We will use the usual notation,

This allows us, for example, to write

From the vanishing torsion condition

we obtain

where \(\Gamma _{\,\alpha \beta }^{\gamma }\) is the Christoffel symbol.

From equations (5) and (6), we find

and the 4-dimensional vanishing torsion condition

From (8), (9) and the Cartan’s second structural equation, \(R^{ab}=d\omega ^{ab}+\omega _{\,c}^{a}\omega ^{cb}\), we obtain the components of the 2-form curvature

where the 4-dimensional 2-form curvature is given by

The torsion-free condition implies that the third term in the Eq. (2) vanishes. This means that the Lagrangian (2) is no longer dependent on the field \(k^{ab}\). So that the Lagrangian (2) has two independent fields, \(e^{a}\) and \(h^{a}\), and it is given by

From Eq. (12) we can see that the Lagrangian contains the Gauss–Bonnet term \(L_{GB}\), the Einstein–Hilbert term \(L_{EH}\) and a term \( L_{H}\) which couples geometry and matter. In fact, replacing (2) and (10) in (12), and using \({\tilde{\varepsilon }}_{mnpq}=\varepsilon _{mnpq4}\), we obtain

Note that in Eq. (13) there is a quadratic term in the curvature given by \(r_{c}d\phi {\tilde{\varepsilon }}_{mnpq}{\tilde{R}}^{mn}{\tilde{R}}^{pq}\) . The action associated with this term can be directly integrated in \(\phi \). In fact,

which represents the 4-dimensional Gauss–Bonnet term. This term is a topological term, so that it does not contribute to the dynamics, and it can be eliminated.

There is also a quadratic term in the curvature in Eq. (15): \( {\tilde{\varepsilon }}_{mnpq}{\tilde{R}}^{mn}{\tilde{R}}^{pq}h^{4}\). Following Ref. [3], we assume that matter has only nonzero components on the 4-dimensional manifold \(\Sigma _{4}\), so that we postulate that the components of the \(h^{a}\)-field are given by

where \(g(\phi )\) is a well behaved function in \(0\leqslant \phi <2\pi \). This means that the quadratic term \({\tilde{\varepsilon }}_{mnpq}{\tilde{R}}^{mn} {\tilde{R}}^{pq}h^{4}\) vanishes.

By replacing (13), (14) and (15) in (12) we find that the action takes the form

where

Since \(f(\phi )\) and \(g(\phi )\) are arbitrary and continuously differentiable functions, and since we are working with a cylindrical variety, if we choose (non-unique choice) \(f(\phi )=g\left( \phi \right) =\ln \left( K+\sin \phi \right) \) with \(K=constant>1\), we find that (19), (20), (21) and (22) lead to

Taking into account that \(L_{ChS}^{(5)}[e,h]\) flows into \(L_{EH}^{(5)}\) when \(l\longrightarrow 0\) [5], we have that action (18) should lead to the action of Einstein–Hilbert when \(l\longrightarrow 0\). From (18) it is direct to see that this occurs when \(A=-1/2\) and \(B=\Lambda /12\) , where \(\Lambda \) is the cosmological constant. In this case, from Eqs. (23), (24) and (25), it is direct to see that

and, therefore the action (18) takes the form

corresponding to a 4-dimensional brane embedded in the 5-dimensional space-time of the Einstein–Chern–Simons gravity. We can see that, when \( l\rightarrow 0\) then \(C\rightarrow 0\), and hence (29) becomes the 4-dimensional Einstein–Hilbert action with cosmological constant.

3 An application to cosmology

In this section, we will find De Sitter cosmological solutions associated with the action (29). We start our analysis by writing the action (29) in tensorial language. The first two terms of the Lagrangian (29) can be written as

where \({\tilde{g}}\) is the determinant of the 4-dimensional metric tensor \( {\tilde{g}}_{\mu \nu }\), and \({\tilde{R}}\) is the 4-dimensional Ricci scalar. The two remaining terms are obtained after some calculations. The results are given by

where \({\tilde{h}}^{m}={\tilde{h}}_{\ \mu }^{m}d{\tilde{x}}^{\mu }\) and \( {\tilde{h}}={\tilde{h}}_{\,\mu }^{\mu }\). Introducing (30, 31 ) in the Lagrangian (29) we obtain

If we consider a maximally symmetric space-time (for instance, the de Sitter’s space), the equation 13.4.6 of Ref. [8] allows us to write

where \({\tilde{F}}\) is an arbitrary function of the 4-scalar field \({\tilde{\varphi }}=\) \({\tilde{\varphi }}({\tilde{x}})\). This means

so that the action (32) takes the form

which corresponds to an action for the 4-dimensional gravity coupled non-minimally to a scalar field. Note that this action has the form

where, \({\tilde{S}}_{g}\) is a pure gravitational action term, \({\tilde{S}}_{g\varphi }\) is a non-minimal interaction term between gravity and a scalar field, and \({\tilde{S}}_{\varphi }\) represents a kind of scalar field potential. In order to write down the action in the usual way, we define the constant \(\varepsilon \) and the potential \(V(\varphi )\) as (removing the symbols \(\sim \) in (35)

where \(\kappa \) is the gravitational constant. This permits to rewrite the action for a 4-dimensional brane non-minimally coupled to a scalar field, immersed in a cylindrical 5-dimensional space-time as

The corresponding field equations are obtained by varying the action (38) and equalizing it to zero. In fact

where no surface terms have been included. This means that equations describing the behavior of the 4-dimensional brane in the presence of the scalar field \(\varphi \) are given by

Note that if \(\varepsilon \rightarrow 0\), then the scalar field potential behaves as a constant \(V_{0}\), and the Einstein’s vacuum field equations with (a modified) cosmological constant are recovered:

where \(\Lambda _{0}=\left( \Lambda +\kappa V_{0}\right) /\left( 1+\varepsilon V_{0}\right) \approx \left( \Lambda +\kappa V_{0}\right) .\)

In order to construct a model of universe based on Eqs. (40)–(41), we consider the Friedmann–Lemaitre–Robertson–Walker metric

where a(t) is the so called “scale factor” and \(k=0,+1,-1\) describes flat, spherical and hyperbolic spatial geometries, respectively. Following the usual procedure, we find that the Friedmann–Lemaitre–Robertson–Walker type equations, are given by

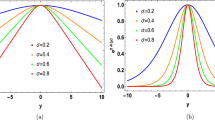

Assuming that \(\partial V/\partial \varphi \ne 0\), Eq. (46) has the solutions

representing the maximally symmetric De Sitter space-time. Here, \( \varepsilon >0\) and \(C_{1}\) is an arbitrary constant, which can be chosen equal to 1.

In the flat case \(k=0\), Eqs. (44) and (45) can be solved exactly for \(\varphi \). Replacing \(a=e^{\sqrt{\kappa /6\varepsilon }t}\) in ( 44), and assuming that V has the form

where \(\lambda \) and n are constants, we obtain the following equation

which has as solution

and therefore

where \(C_{2}\) is an arbitrary constant which can be chosen equal to 1.

On the other hand, if we replace \(a=e^{\sqrt{\kappa /6\varepsilon }t}\), (48), (50) and (51) in Eq. (45), we see that the equality \(0=0\) is satisfied, which means that no constraints are imposed on the constants n and \(\lambda \) in the scalar field potential V.

Consequently, the solution of the system of equations (44)-(46) is given by

This solution describes an accelerated flat expanding universe in the presence of a scalar field that exhibits an exponential behavior.

Observe that solution (51) is also valid for late time cosmology in the cases with spherical and hyperbolic spatial geometries, namely \(k=\pm 1\), where \(\frac{{\dot{a}}}{a}\approx \sqrt{\frac{\kappa }{6\varepsilon }}=\sqrt{ \frac{\Lambda }{3}}\).

4 Concluding remarks

In this work, we have obtained an action and its corresponding field equations, for a 4-dimensional brane embedded in the 5-dimensional space-time of the Einstein–Chern–Simons theory of gravity. This framework leads to the 4-dimensional general relativity with cosmological constant in the limit \(l\rightarrow 0\). We have also obtained an interpretation of the \(h^{a}\) matter field present in the Einstein–Chern–Simons gravity action, which was related to a scalar field. As an application, the Friedmann–Lemaitre–Robertson–Walker equations for cosmology were found and some De Sitter accelerated solutions were obtained, considering a scalar field potential with the form \(V=\lambda \varphi ^{n}\), where \(\lambda \) and n represent arbitrary constants.

In Ref. [9] it was found that the Lagrangian (2) can be written in the form (90) (see appendix). From (90) we can see that kinetic terms corresponding to the fields \(h^{a}\) and \(k^{ab}\), absent in the Lagrangian (2), are present in the surface term of the Lagrangian (90) through equation (91). This situation is common to all Chern–Simons theories. This has the consequence that the action (38) does not have the kinetic term for the scalar field \( \varphi \).

It could be interesting to add a kinetic term to the 4-dimensional brane action. In this case, the action (38) takes the form

The corresponding field equations are given by

where \(T_{\mu \nu }^{\varphi }\) is the energy-momentum tensor of the scalar field

and the rank-2 tensor \(H_{\mu \nu }\) is defined as

Note that if \(\varepsilon \rightarrow 0\), then the Einstein field equations with cosmological constant, in the presence of a scalar field, are recovered,

Following the usual procedure, we find that the Friedmann–Lemaitre–Robertson–Walker type equations are

From here, we can see that in the limit \(\varepsilon \rightarrow 0\), the Friedmann equations with a scalar field are recovered (see e.g. Ref. [10]):

In the case of a constant scalar field \(\varphi =\varphi _{0}\), we have that \(\ddot{\varphi }={\dot{\varphi }}=0\) and \(V(\varphi _{0})=V_{0}\). Then, we find the following solution for the system (59)–(61):

where C is an arbitrary constant, \(\varepsilon >0\) and the constant scalar field potential takes the form

If we wish to interpret the scalar field \(\varphi \) as a Klein–Gordon particle, with potential \(V\left( \varphi \right) =\left( m^{2}/2\right) \varphi ^{2}\), then the mass of this field has to be given by

where \(\kappa -2\varepsilon \Lambda >0.\)

On the another hand, in the case that \(k=0\) and the scalar field is non-constant, equations (59)–(61) take the form

A solution for this system can be found by considering first

in equation (70). The solution of (71) for the scale factor is given by

where \(C_{1}\) is an arbitrary constant and \(\varepsilon >0\).

Conversely, the replacement of (71) and (72) in (70), leads to the equation for the scalar field

whose solution is

where \(C_{2}\) and \(C_{3}\) are arbitrary constants.

Choosing \(C_{1}=C_{2}=1\) and \(C_{3}=0\), we arrive at the following solution for equation (70),

which describes a De Sitter universe in exponential accelerated expansion, in presence of a scalar field that exhibits an exponential decay.

For consistency, the solution (75) must also be a solution of the equations (68) and (69). By replacing (75) in (68 ), and assuming that the potential of the scalar field is given by

with \(\lambda \) and n constants, we obtain the following equation

which is satisfied choosing the cosmological constant and the potential as follows

According to equations (76) and (78), we see that

Observe that \(\Lambda =\kappa /2\varepsilon >0,\) then \(\lambda <0\). Therefore, the scalar field \(\varphi \), with potential

might be identified with a tachyon, a hypothetical particle with imaginary mass, whose speed is higher than the speed of light. In this case, the mass of the particle is

Note that equation (69) is consistent with the results found. The solution (75) can be rewritten in terms of the cosmological constant as

Finally, it is worth noting that in Ref. [11] a 5-dimensional Chern–Simons action for gravity, invariant under the Poincaré group enlarged by an Abelian ideal, was found. Equations and solutions found in the present article, obtained from Einstein–Chern–Simons gravity [5] , can be easily replicated for the theory in Ref. [11], through the replacement \(\alpha _{1}=0\) and \(\alpha _{3}=l=1\).

It might be of interest to note some similarities and differences between the four-dimensional Lagrangian of the action (29) and the Lagrangian of the gravity theory based on the Maxwell algebra in four dimensions proposed by Azcarraga, Kamimura and Lukierski in Ref. [12].

The Lagrangian of the action (29) is obtained from the so called Einstein–Chern–Simons Lagrangian (90) for the \({\mathfrak {B}}\) Lie algebra (86), whose generators are given by \(\left\{ J_{ab},P_{a},Z_{ab},Z_{a}\right\} \) [5].

The gravity theory of Ref. [12] is based on the Maxwell algebra whose generators are given by \(\left\{ J_{ab},P_{a},Z_{ab}\right\} .\) This algebra can also be obtained from the anti de Sitter (AdS) algebra via the mentioned S-expansion procedure.

The corresponding one-form gauge connection and the two-form curvature are given by

where \(T^{a}=de^{a}+\omega _{ \ c}^{a}e^{c}=\mathrm {D}_{\omega }e^{a}\) , \(R^{ab}=d\omega ^{ab}+\omega _{ \ c}^{a}\omega ^{cb},\) \({\mathcal {F}} ^{ab}=\mathrm {D}_{\omega }k^{ab}+\Lambda e^{a}e^{b},\) which allows us to construct the Lagrangians (29) of the Ref. [12]:

where \({\mathcal {F}}^{ab}\equiv F^{ab}\) and \(k^{ab}\equiv A^{ab}\).

Since Maxwell’s algebra is contained in algebra \({\mathfrak {B}}\), it would be reasonable to expect that the action (84) should be a particular case of the action (29). However, this fact is not observed when the corresponding Lagrangians are compared. The reason for this discrepancy is due to the fact that we have imposed the freedom of torsion condition on Lagrangian (2). The imposition of this condition eliminates from the Lagrangian (2) the field \(k^{ab}\equiv A^{ab}\). Comparison of the Lagrangians (29) and (84) shows that they have in common only the Einstein-Hilbert and the cosmological terms. An interesting problem could be consider equation (2) without imposing the torsion-free condition, carry out the same procedure that leads to a Lagrangian analogous to Lagrangian (29) and then comparing it with the Lagrangian (84).

It may be also of interest to note that although the two Lagrangians contain a cosmological term, they have different origins. The cosmological term of the Lagrangian (84) has its origin in the commutation relation \(\left[ P_{a},P_{b}\right] =Z_{ab}\), this means in the field \(k^{ab}\), while the cosmological term of the Lagrangian (29) appears when the 5 -dimensional Randall–Sundrum metric is introduced.

It might be of interest to note that the fields \(k^{ab}\), associated with the generators \(Z_{ab}\), plays a role similar to that played by the field \( A^{ab}\) in Ref. [12], that is, to introduce a cosmological term in an alternative way that generalizes standard gravity. However, as we have already mentioned, this term is not present in our approach. On the other hand, the \(h^{a}\) field, associated with the generators \(Z_{a},\) plays the role of a scalar field in the case of maximally symmetric space-times.

Data Availability Statement

This manuscript has no associated data or the data will not be deposited. [Authors’ comment: The reason why there is no data is because our article is a theoretical study and no experimental data has been listed.]

References

T. Kaluza, Sitzungsber. Preuss. Akad. Wiss. Berlin (Math. Phys.) 966 (1921)

O. Klein, Z. Phys. 37, 895 (1926)

L. Randall, R. Sundrum, Phys. Rev. Lett. 83(17), 3370 (1999)

L. Randall, R. Sundrum, Phys. Rev. Lett. 83(17), 4690 (1999)

F. Izaurieta, P. Minning, A. Pérez, E. Rodríguez, P. Salgado, Phys. Lett. B 678, 213 (2009)

F. Izaurieta, E. Rodríguez, P. Salgado, J. Math. Phys. 47, 123512 (2006)

F. Izaurieta, A. Pérez, E. Rodríguez, P. Salgado, J. Math. Phys. 50, 073511 (2009)

S. Weinberg, Gravitation and Cosmology (Wiley, New York, 1972)

M. Cataldo, J. Crisostomo, S. del Campo, F. Gomez, C. Quinzacara, P. Salgado, Eur. Phys. J. C 74, 3087 (2014)

A.A. García, A. García-Quiroz, M. Cataldo, S. del Campo, Phys. Rev. D 69, 041302(R) (2004)

J.D. Edelstein, M. Hassaïne, R. Troncoso, J. Zanelli, Phys. Lett. B 640, 278–284 (2006)

J.A. de Azcárraga, K. Kamimura, J. Lukierski, Phys. Rev. D 83, 124036 (2011)

J. Zanelli, Lecture notes on Chern-Simons (super)gravities, second edition. arXiv:hep-th/0502193

F. Izaurieta, E. Rodriguez, P. Salgado, Lett. Math. Phys. 80, 127 (2007)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by Universidad de los Lagos, Chile. Three of the authors (RD, FG, MP) were supported by Universidad de Los Lagos Grant # R12/18. One of the authors (PS) was supported in part by FONDECYT Grants No. 1180681 from the Government of Chile. The authors would like to thank Luis Ruiz-Pailalef for the careful reading of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

A ChS Lagrangian in \(d=2n+1\) dimensions is defined to be the following local function of a one-form gauge connection \({\varvec{A}}\):

where \(\left\langle \cdots \right\rangle \) denotes a invariant tensor for the corresponding Lie algebra, \(F=dA+AA\) is the corresponding the two-form curvature and k is a constant [13].

Some time ago was shown that the standard, five-dimensional General Relativity can be obtained from Chern–Simons gravity theory for a certain Lie algebra \({\mathfrak {B}}\) [5], whose generators \(\left\{ J_{ab},P_{a},Z_{ab},Z_{a}\right\} \) satisfy the commutation relationships

This algebra was obtained from the anti de Sitter (AdS) algebra and a particular semigroup S by means of the S-expansion procedure introduced in Refs. [6, 7].

In order to write down a Chern–Simons lagrangian for the \({\mathfrak {B}}\) algebra, we start from the one-form gauge connection

and the two-form curvature

A Chern–Simons lagrangian in \(d=5\) dimensions is defined to be the following local function of a one-form gauge connection \({\varvec{A}}\):

where \(\left\langle \cdots \right\rangle \) denotes a invariant tensor for the corresponding Lie algebra, \(F=dA+AA\) is the corresponding the two-form curvature and k is a constant [13].

Using theorem VII.2 of Ref. [6], and the extended Cartan’s homotopy formula as in Ref. [14], and integrating by parts, it is possible to write down the Chern–Simons Lagrangian in five dimensions for the \({\mathcal {B}}\) algebra as [5, 9]

where the surface term \(B_{\text {EChS}}^{(4)}\) is given by

and where \(\alpha _{1}\), \(\alpha _{3}\) are parameters of the theory, l is a coupling constant, \(R^{ab}=d\omega ^{ab}+\omega _{b}^{a}\) corresponds to the curvature 2-form in the first-order formalism related to the 1-form spin connection, and \(e^{a}\), \(h^{a}\) and \(k^{ab}\) are others gauge fields presents in the theory.

Finally it might be necessary to notice that:

(a) The lagrangian is split into two independent pieces, one proportional to \(\alpha _{1}\) and the other to \(\alpha _{3}.\) The piece proportional to \(\alpha _{1}\) corresponds to the Inönü–Wigner contraction of the Chern–Simons Lagrangian corresponding to AdS-algebra, and therefore it is the Chern–Simons Lagrangian for the Poincaré-Lie algebra \(\mathrm {ISO}\left( 4,1\right) \). The piece proportional to \(\alpha _{3}\) contains the Einstein–Hilbert term \(\varepsilon _{abcde}R^{ab}e^{c}e^{d}e^{e}\) plus non-linear couplings between the curvature and the bosonic “matter” fields \(k^{ab}\) and \(h^{a}\), where the parameter \(l^{2}\) can be interpreted as a kind of coupling constant.

(b) When the constant \(\alpha _{1}\) vanishes, the lagrangian (90) almost exactly matches the one given in Ref. [11], the only difference being that in our case the coupling constant \(l^{2}\) appears explicitly in the last two terms.

The presence or absence of the coupling constant l in the lagrangian could seem like a minor or trivial matter, but it is not. As the authors of Ref. [11] clearly state, the presence of the Einstein–Hilbert term in this kind of action does not guarantee that the dynamics will be that of general relativity. In general, extra constraints on the geometry do appear, even around a “vacuum” solution with \(k^{ab}=h^{a}=0\). In fact, the variation of the lagrangian, modulo boundary terms, can be written as

Therefore, when the condition \(\alpha _{1}=0\) is chosen, the torsionless condition imposed, and a solution without matter \((k^{ab}=h^{a}=0\)) is picked out, we are left with

In this way, besides general relativity equations of motions \(\epsilon _{abcde}R^{ab}e^{c}e^{d}=0,\) the equations of motion of pure Gauss–Bonnet theory \(\varepsilon _{abcde}R^{ab}R^{cd}=0\) do also appear as an anomalous constraint on the geometry.

It is at this point where the presence of the coupling constant l makes the difference. In the present approach, it does play the role of a coupling constant between geometry and “matter”. For this reason, in this case the limit \(l\rightarrow 0\) leads to the Einstein–Hilbert term in the Lagrangian,

In the same way, when we impose the weak limit of coupling constant, \( l\rightarrow 0,\) the extra constraints just vanish, and \(\delta L_{\mathrm {CS }}^{\left( 5\right) }=0\) lead us to just the Einstein–Hilbert dynamics in the vacuum,

It is interesting to observe that the argument given here is not just a five-dimensional accident; at every odd dimension, it is possible to realize the S-expansion in the way sketched here, to take the weak limit of coupling constant, \(l\rightarrow 0,\) and recover Einstein–Hilbert gravity.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Funded by SCOAP3

About this article

Cite this article

Díaz, R., Gómez, F., Pinilla, M. et al. Brane gravity in 4D from Chern–Simons gravity theory. Eur. Phys. J. C 80, 546 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-020-8104-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-020-8104-6