Abstract

Recent studies have increasingly focused on the cognitive benefits of acute physical activity, particularly in enhancing creative thinking. Despite extensive research linking physical activity and creative cognition, significant gaps remain in understanding how specific types and intensities of physical activities influence this relationship. This review aims to synthesize the current findings, highlighting the notable impact of various physical activities on creative thinking. One key finding is the enhancement of divergent thinking, a critical component of creativity, through activities like walking at a natural pace. Moderate intensity aerobic exercise and dance, though based on limited studies, also appear to facilitate divergent thinking. Additionally, vigorous intensity aerobic exercise may enhance secondary aspects of divergent thinking, including the quantity and flexibility of idea generation. However, the review also identifies multiple research gaps, especially on the effects of resistance exercise and structured moderate to vigorous intensity aerobic exercise on creative thinking, pointing to an area ripe for future exploration. Recognizing the critical importance of creative thinking, it becomes essential to understand how different physical activities, and their intensity levels, affect creative cognition. This knowledge can guide both academic research and practical applications, offering valuable insights for targeted strategies aimed at enhancing cognitive function and creativity through physical activity in real-world settings such as classrooms and workplaces. The review underscores the need for a more comprehensive exploration of this topic, which could have significant implications for the fields of cognitive and exercise psychology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Creative thinking, often regarded as the bedrock of problem-solving, innovation, and adaptive thinking [58, 124], has gained increasing prominence in our rapidly changing world. In an era marked by technological advancements and continuous shifts in societal and professional landscapes, the ability to think creatively is not just advantageous but essential. It is this ability that enables individuals to navigate complex challenges, generate novel ideas, and foster innovative solutions [58, 69, 115]. The foundation of scientific creativity research was laid by Guilford in [59]. Guilford identified two key components of creative thinking: divergent and convergent [61]. This distinction has been instrumental in guiding research in this field for decades [113].

Divergent thinking, which involves generating a multitude of novel ideas, encourages stepping beyond conventional limits to view a problem from diverse perspectives, considering a wide array of solutions [112]. This process can manifest verbally, as evaluated by tests like the Alternate Uses Test AUT [60], or figuratively, as in parts of the Torrance Test of Creative Thinking [120]. For instance, in the AUT, participants are prompted to think creatively and list as many unique and unconventional uses as possible for everyday objects, such as 'bricks' and 'tin cans'. The evaluation of their responses is multi-faceted, focusing on several key indicators of creativity. These include: fluency, which measures the sheer number of uses a participant can generate, flexibility, which evaluates the diversity of conceptual categories from which the suggested uses originate; originality, which assesses the rarity or uniqueness of the proposed uses; and elaboration, which looks at the level of detail and development in each proposed use. These criteria collectively provide a comprehensive assessment of an individual’s creative thinking abilities. Originality, particularly, stands out as a central or primary aspect of divergent thinking [97, 112]. It not only measures the uniqueness of the ideas but also their qualitative richness, thereby capturing the essence of true creative thought.

On the other hand, convergent thinking is the process of logically narrowing down multiple ideas to identify the most viable, single solution, assessing the feasibility and practicality of each option. Tools such as the Remote Association Test RAT [82, 83], the Compound Remote Associates test CRA [19], and insight problem-solving tasks like matchstick arithmetic problems [72] are commonly used to evaluate convergent thinking. A detailed overview of these evaluation methods is presented in Table 1.

It has been suggested that whereas divergent thinking is supported by associative abilities and cognitive flexibility [6, 11, 45], convergent thinking is more reliant on working memory and fluid intelligence [45, 55, 75]. Importantly, research indicates that scores on divergent and convergent thinking tests are predictive of real-life creative potential and achievement, as well as creativity as assessed by others [40, 57, 103, 114].

Complementing this, various studies have illuminated factors that can facilitate creative thinking, including positive mood [8, 43, 63], contact with nature [7, 127], and listening to music [48, 108]. Building upon this understanding, it is important to explore other practical methods that can enhance creative thinking. One such notable factor is physical activity. Recent research points to the cognitive benefits of acute physical activity, especially in enhancing creative thinking [1, 111].

The intricate relationship between physical activity and cognitive function has captivated the attention of researchers and practitioners for decades [25, 26, 107]. This fascination stems from an acknowledgment of the profound impact that physical activity can have on the human brain and its cognitive capacities. In the realm of scientific inquiry, recent years have seen a surge in research dedicated to unraveling the nuances of this relationship [28, 33]. The findings have consistently highlighted the multitude of cognitive benefits from engaging in acute physical activity [24, 62, 64, 74, 87]. These benefits span various cognitive domains, including enhancements in memory and learning [77, 109, 123], executive functions [62, 76, 87] especially in terms of processing speed [64], and attention [22, 49]. These benefits across diverse cognitive domains have the potential to transform into higher-level cognitive enhancements, which raises the possibility that engaging in acute physical activity could lead to an elevation in advanced cognitive functions, such as creative thinking.

A substantial number of studies have delved into the link between physical activity and creative thinking, offering intriguing insights [1, 111]. In a meta-analysis, Rominger et al. [111] synthesized existing studies to quantify this relationship. Aggregating various forms of physical activity, ranging from light to vigorous intensities and including activities like walking, running, dance, and yoga, they concluded that a single bout of physical activity significantly enhances divergent thinking. The effect size, as measured by Hedges’ g, was found to be in the small to medium range (0.37). While Rominger et al. [111] meta-analysis offers valuable insights, it is important to note some limitations in their approach for a more comprehensive understanding. Specifically, their methodology did not differentiate the impact based on specific intensity or type of activity. Moreover, they focused solely on divergent thinking, thereby not addressing convergent thinking.

These gaps in research are significant because, firstly, not all physical activities are created equal in their cognitive impact. The types of activities—ranging from aerobic exercises such as walking, running, and cycling to resistant exercises as well as more mindful practices like yoga—differ vastly in their physiological and psychological effects [28]. For instance, unlike aerobic exercise, strength training does not reliably increase the concentration of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), a growth factor that plays a crucial role in synaptic plasticity underlying learning and memory [28, 102]. Similarly, the intensity of these activities, whether low, moderate, or high, also plays a crucial role in determining their cognitive outcomes. For instance, research has shown an inverted-U shaped relationship for exercise-induced cognitive enhancements, indicating an optimal exercise intensity for cognitive benefits [81]. Beyond this intensity, further cognitive improvements may not occur, or performance may even decline. Understanding these variances is vital for crafting targeted strategies that leverage physical activity for cognitive enhancement, particularly in the realm of creative thinking.

Secondly, as divergent and convergent thinking are two distinct components of creative thinking, one may also expect that they might be influenced differently by physical activities. Initial evidence of this distinction came from Oppezzo and Schwartz [97], one of the most cited works in this domain. In their study, Oppezzo and Schwartz [97] found that a single bout of walking specifically enhanced divergent thinking, while it did not show a similar effect on convergent thinking. This finding suggests a selective rather than a universal impact of physical activity on cognitive processes. Oppezzo and Schwartz [97]'s work highlights the need for more nuanced research in how different physical activities specifically affect various facets of creative thinking.

Therefore, this narrative review aims to explore the specific ways in which different types of acute physical activities and their intensities influence both divergent and convergent thinking. Despite the seemingly narrow focus, acute studies provide valuable insights into the immediate cognitive impacts of physical activity. Such insights are crucial for understanding the short-term cognitive enhancements that can be leveraged in real-world settings. For example, in educational contexts, integrating brief physical activities into classroom routines can stimulate immediate creative thinking among students. This can be particularly beneficial during brainstorming sessions or when engaging in creative problem-solving tasks, where an immediate boost in cognitive flexibility and divergent thinking is advantageous. Similarly, in the workplace, incorporating short physical activity breaks can rejuvenate employees' cognitive abilities, especially before undertaking tasks that demand creativity or innovative problem-solving. This approach is especially pertinent in dynamic sectors like design, marketing, or software development, where rapid and divergent thinking is frequently required. In light of these practical applications, our review emphasizes how these short-term cognitive benefits from acute physical activity can be effectively harnessed in everyday environments such as classrooms and workplaces. It promises to inform educators and individuals about optimizing physical activity regimes for cognitive and creative enhancement, thereby contributing to personal and professional growth in our complex and dynamic world.

2 Methods

Studies up to the end of 2021 were sourced from two prior studies, one extensive literature review conducted by our team [1] and the other systematic review and meta-analysis by Rominger et al. [111]. Studies published between January 2022 and November 24th, 2023 were identified through a thorough search on PubMed and Scopus. The search strings, limited to Title/Abstract, included terms related to physical activity and creativity, as provided below:

(physical activity OR bodily movement OR aerobic exercise OR exercise program OR dancing OR physical fitness OR walk* OR running OR high intensity interval training OR sprint interval training OR resistance training OR resistance exercise OR strength training OR yoga) AND (creativity OR creative thinking OR creative potential OR creative ideation OR divergent thinking OR alternate use* OR alternative use* OR originality OR convergent thinking OR insight problem solving OR remote association OR compound remote associates).

Using these search terms, we also conducted another literature search with Google Scholar. Studies were included based on the following criteria: (1) Investigation of the effects of acute physical activity; (2) Evaluation of creative thinking with objective experimental tasks; (3) Utilization of either between-subjects or within-subjects controlled designs, or a group-level allocation approach, with the inclusion of a control group being mandatory; (4) Studies were required to be in English and conducted on human subjects.

From the eligible studies, we extracted data on subjects, design, exercise and control interventions, creativity evaluation, and primary results. Exercise interventions were systematically categorized into seven distinct types/intensities: natural walking (no specific restrictions on the speed or manner of walking), low, moderate, vigorous, and maximal intensity activities, dancing, and yoga.

We adhered to the guidelines of the American College of Sports Medicine [4] for defining exercise intensities, categorizing them as low, moderate, vigorous, and maximal. Specifically, we merged 'very light' and 'light' activities into the 'low intensity' category. This was due to the overlapping intensity ranges observed in the studies we reviewed. Low intensity was defined as less than 39% heart rate reserve (HRR) or less than 63% maximum heart rate (HRmax), with a rating of perceived exertion (RPE) of 11 or less on a 6–20 scale, or 3 or less on a 0–10 scale. Moderate intensity was characterized by 40–59% HRR, 64–76% HRmax, and an RPE of 12–13 on a 6–20 scale or 4–5 on a 0–10 scale. Vigorous intensity was defined as 60–89% HRR, 77–95% HRmax, and an RPE of 14–17 on a 6–20 scale or 6–7 on a 0–10 scale. Maximal intensity was defined as 90% or more HRR, 96% or more HRmax, and an RPE of 18 or higher on a 6–20 scale or 8 or higher on a 0–10 scale (or requiring maximum effort).

In cases where studies did not standardize exercise interventions but provided heart rate data, we converted this to age-estimated % HRmax for intensity approximation [4].

Natural walking, dancing and yoga were treated as unique categories due to their distinct nature and often unreported exercise intensities. For example, dancing involves complex rhythmic movements often synchronized with music, and yoga combines physical activity with mindfulness [28].

Divergent thinking was evaluated using various measures, such as fluency (the number of generated uses), flexibility (the number of different types/categories of uses), originality (the number of unique types/categories of uses), and elaboration (details in the generated uses). While many studies reported one or more of these measures, we primarily focused on originality, considering it as a central or primary aspect of divergent thinking [97, 112], with the others serving as secondary measures.

3 Results

21 studies containing 24 experiments were eligible. The general information of each study and their primary results are summarized in Table 2. Among the studies analyzed, 11, accounting for 52%, were published after the year 2020, indicating a growing interest in this field. In terms of participant demographics, the studies show a diverse geographical spread: six were conducted in the USA, five in India, two each in the UK and Japan, and one each in Spain, Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, Israel, and China. The majority of experiments (21 among 24) involved adult participants, with seventeen specifically engaging undergraduate and/or graduate students. Three studies were conducted with children. 13 experiments utilized a randomized within-subjects design and nine employed a randomized between-subjects design. Additionally, two experiments conducted group-level allocations, with one of these being randomized.

Six experiments focused on investigating the effects of natural walking, which included one study on stair-climbing. Furthermore, there were five experiments involving low intensity aerobic exercise, three examining moderate intensity aerobic exercise, two dedicated to vigorous intensity aerobic exercise, and one employing cycling at maximal effort. Six studies explored the impact of dance, and two examined the effects of yoga. No study has specifically investigated the effects of resistance exercise.

Out of the 22 experiments that assessed divergent thinking, 17 utilized either the original or an adapted form of the AUT for verbal divergent thinking evaluation. Two experiments employed a subset of the Torrance Test of Creative Thinking to assess figural divergent thinking. Other divergent thinking measures included Barron’s Symbolic Equivalence Task, and other variates of the AUT in the broader context, including the Instances Creativity Task, the J&D Idea Generation Test, the Consequences Imagination task, the Design Improvement Task, along with tasks involving realistic problem presentation and generation. For convergent thinking evaluation, 10 experiments were conducted, of which five used the Remote Association Test, one the Compound Remote Associates test, and three involved insight problem-solving tasks.

Concerning the timing of the creativity assessments in the experiments, seven were administered during the exercise period. 15 tests were conducted immediately after the exercise session, while in five experiments, the creativity tests were delayed, ranging from a 1-min to approximately a 6-h interval post-exercise.

The main findings from the eligible experiments are stratified and summarized in Tables 3 and 4, organized according to activity type, intensity, and the measures of creative thinking used.

3.1 Effects on divergent thinking

Natural walking As shown in Table 3, a key finding from our review is the consistently positive effect of natural walking on enhancing central measures of divergent thinking, namely originality, as evidenced in all six experiments that investigated this aspect [80, 97, 128]. These studies, incorporating four different tasks, were conducted by three distinct research teams using between-subjects as well as within-subjects designs. They consistently reported significant improvements in divergent thinking in various settings: both during and immediately after walking on a treadmill [97] or along a university campus path [97], while walking inside a room [128], and immediately after a round-trip stair-climbing [80].

Out of the three studies that investigated secondary aspects of divergent thinking, including fluency and flexibility, two experiments [88, 128] observed a significant enhancement during natural or free walking. In contrast, a third study [80] did not detect any impact in a post-activity assessment.

Notably, the durations of walking that facilitated various measures of divergent thinking were merely 3–4 min [80, 97]. Additionally, walking along an 8-shaped, approximately 17-m-long path without speed restrictions was also found to enhance divergent thinking [128].

Low intensity The impact of exercise intensity on creative thinking shows varied results according to our analysis. Low intensity aerobic exercise, including cycling and structured treadmill walking, did not seem to influence any measures of divergent thinking, as shown by four experiments from three research teams [21, 36, 52, 53].

Moderate intensity Two separate experiments focused on moderate intensity aerobic exercise reported significant enhancements in various aspects of divergent thinking. In a study by Román et al. [110], notable improvements were observed in originality, both verbal and figural, during physical education-based interventions with children. This study also reported increases in verbal fluency, flexibility, and a composite score for figural tasks. The finding on the composite score is consistent with earlier research conducted with undergraduate students [12]. It is important to note that Román et al. [110] assessed exercise intensity using only subjective measures, specifically the Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE).

Vigorous intensity In studies focusing on vigorous intensity aerobic exercise, only one investigated originality, finding no significant enhancement [1]. Regarding secondary aspects of divergent thinking, among the two relevant studies, Netz et al. [92] identified a significant increase in fluency, whereas Aga et al. [1] noted an improvement in flexibility. Notably, the methodology of Aga et al. [1] involved a graded exercise test, leading to variable exercise intensities rather than a consistent level throughout the intervention.

Maximal intensity In a study that examined the impact of cycling at maximal effort, not only was there no enhancement observed, but a decline in flexibility was noted [36].

Dance Within the adult studies evaluating AUT originality, three out of four studies reported a significant enhancing effect [15,16,17]. For studies focusing on secondary measures of AUT in adults, three out of four studies demonstrated significant enhancement in at least one measure [15, 17, 117]. Interestingly, the fourth study in this group, Campion & Levita [21], uniquely found a positive correlation between increases in positive affect and fluency (r = 0.637, p = 0.011). However, the same study did not observe any significant effects on figural divergent thinking.

In the context of school-aged children, mixed outcomes were observed. One study by Bollimbala et al. [13] did not report any significant effects on AUT measures. Conversely, a study by Österberg and Olsson [98] demonstrated enhanced originality and fluency in a different idea generation task.

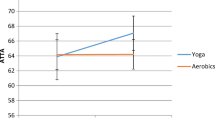

Yoga Among the two studies available, one by Bollimbala et al. [14] demonstrated a significant enhancing effect on originality, fluency, and flexibility in the AUT. However, these findings were not replicated in a subsequent study by the same team [16].

3.2 Effects on convergent thinking

Natural walking As detailed in Table 4, natural walking did not change [80] or even worsened [97] convergent thinking. It is important to note these studies used different tasks: the former employed insight problem-solving tasks, whereas the latter utilized the Compound Remote Associates Test.

Low intensity Low intensity aerobic exercise, including cycling and structured treadmill walking, did not seem to influence convergent thinking, as shown by two studies employing the RAT [36, 52] and one study using insight problem solving tasks [66].

Moderate intensity A study by Frith et al. [54] reported a positive effect on RAT following a 15-min session of treadmill running.

Vigorous intensity One study examining vigorous intensity aerobic exercise did not demonstrate a significant effect on convergent thinking evaluated through insight problem-solving tasks [1]. However, it did reveal an intriguing aspect in its exploratory analysis: a positive correlation between post-exercise mood and convergent thinking, with correlation coefficients of 0.503 and 0.647 for feelings of pleasure and vigor, respectively.

Maximal intensity In an experiment that investigated the impact of cycling at maximal effort on RAT, no significant effect was observed in participants with exercise habits while a detrimental effect was noted in those without exercise habits [36].

Dance Bollimbala et al. [13] identified a significant enhancing impact of dance on RAT in children. However, a later study by the same team [15], focusing on adult MBA students, did not replicate these findings.

Yoga A study examining the effect of yoga found no significant impact on RAT [14].

4 Discussion

This review explores the increasingly recognized link between acute physical activity and creative thinking, a topic that has captured the attention of both cognitive and exercise psychology communities. While there has been considerable research in this domain, significant gaps persist in our understanding of how different types and intensities of physical activities uniquely affect creative thinking processes.

4.1 Key findings and their implications

Our analysis reveals that natural walking, a simple yet effective form of physical activity, significantly enhances divergent thinking. Although based on a relatively small pool of studies, there is also suggestive evidence that moderate intensity aerobic exercise and dance positively influence divergent thinking. Notably, the beneficial effects of dance appear to be confined to adult population. In addition, vigorous aerobic exercise is associated with improvements in secondary aspects of divergent thinking, such as the quantity and flexibility of generated ideas. These observations align with a recent study of chronic physical activity showing that while habitual vigorous activities are associated with improvement in fluency and flexibility in the AUT, only walking is associated with heightened originality, the central aspect of divergent thinking [27].

These findings are pivotal, as divergent thinking is fundamental to creativity, fostering the generation of novel and varied ideas. The implications of these findings are substantial. For instance, in educational settings, incorporating walking, moderate to vigorous aerobic exercise, or dance into curricula could be a strategy to enhance creative capacities among students. Similarly, in professional environments, encouraging physical activities during breaks could foster a culture of innovation and adaptive thinking.

4.2 Identifying research gaps

While the current insights are valuable, a significant research gap remains regarding the effects of resistance exercise and structured moderate to vigorous intensity aerobic exercise on creative thinking. While it is evident that activities like natural walking and dance can bolster divergent thinking, there remains a gap in our understanding regarding the optimal intensity and duration of physical activities that yield the greatest benefits. This uncertainty underscores the need for further research to identify the specific parameters of physical activity that maximize cognitive enhancement. These unexplored areas present a promising opportunity for future studies. Given the diverse neurobiological impacts attributed to varying intensities and types of resistance versus aerobic exercise [28], further research in this domain could unveil key insights into the most effective physical activities for specifically enhancing different facets of creative thinking. Additionally, when evaluating the effects of specific exercise intensities, it is imperative that future research employs standardized methods for prescribing and reporting exercise interventions. Guidelines provided by the American College of Sports Medicine [4] offer a robust framework for this purpose. Currently, apart from three studies that utilized heart rate reserve to prescribe exercise intensity [53, 54, 92], many studies either lack standardized procedures or do not use measures indicative of exercise intensity, such as heart rate or the RPE. Ideally, even in studies involving naturalistic activities like walking and dance, it is essential to measure and report RPE and heart rate, preferably using age-estimated HRmax. Such standardization is crucial for ensuring the reliability and comparability of research findings.

Another significant knowledge gap exists regarding the influence of mood changes on the enhancement of creative thinking following acute physical activity. While there is promising evidence suggesting that improved mood may underlie the beneficial effects of physical activity on creativity, as supported by studies linking positive mood to enhanced creative thinking [3, 8, 37, 43, 63, 93, 100] and productivity [32], this relationship remains under-explored. This area of study warrants further investigation, especially considering that other activities known to boost creative thinking, such as engaging with nature [7, 127] and listening to music [48, 108], are also associated with improvements in mood [108, 126]. Understanding the interplay between mood, physical activity, and creativity could provide valuable insights into optimizing conditions for creative thinking in various contexts. Among the studies reviewed, positive mood post-exercise has been correlated with increased fluency in the AUT [21] and improved convergent thinking performance after vigorous aerobic exercise [1], both showing substantial correlation coefficients. However, a mediation analysis in one study [1] investigating the role of mood in the flexibility-enhancing effects of vigorous activity did not yield significant results. The small sample sizes in these studies (less than 20 participants) limit the robustness of their conclusions. Therefore, further research with larger sample sizes is needed to thoroughly investigate these relationships.

A third research gap concerns the ambiguity surrounding which types of acute physical activity specifically enhance convergent thinking. Of the nine available studies, only two have confirmed an enhancing effect: a 15-min moderate intensity treadmill running session in adults [54], and a 20-min dance session in children [13]. Moreover, despite the clear distinction between divergent and convergent thinking, it remains enigmatic why certain activities, such as natural walking, enhance divergent but not convergent thinking [80, 97].

Convergent thinking involves refining a multitude of ideas into a single, effective solution. It is characterized by the search for the most accurate or conventional answer to complex problems with multiple constraints. This form of cognitive process not only draws upon existing knowledge but also transforms it into novel ideas [41]. Assessment of convergent thinking is typically conducted through the Remote Associates Task [82, 83] and the Compound Remote Associates Test [19], with occasional use of insight problem-solving tasks [72]. Given that convergent thinking is more reliant on working memory and fluid intelligence [45, 55, 75], it may be hypothesized that moderate to vigorous intensity exercise, known for its peak cognitive benefits, might enhance this cognitive function [28, 90]. This hypothesis aligns with studies that observed an improvement in convergent thinking following moderate-intensity activities like treadmill running [54] and dance [13]. However, the full extent of this relationship remains an area for future research to explore and confirm.

A fourth notable gap lies in the scant research involving specific demographics like children, adolescents, the working population, and the elderly. Among 21 studies reviewed, the majority (seventeen) involved undergraduate students. This oversight is notable as children and adolescents are in critical phases of development and learning, the working population faces diverse real-world problem-solving challenges, and the elderly contend with cognitive decline. Conducting more comprehensive research within these varied populations is essential to fully understand the broader implications of physical activity on cognitive processes across different life stages.

In the few studies that have included children, findings have been mixed but promising. Among three studies, two demonstrated an improvement in divergent thinking: one through a 45-min physical education-based intervention at moderate intensity [110], and another via a 3-min free dance session [98]. Conversely, a third study employing a 20-min dance session observed an enhancement in convergent thinking, but not in divergent thinking [13]. These results suggest that, as in adults, the specific duration and intensity of physical activity required to boost divergent and convergent thinking in children is a complex issue, necessitating further investigation.

Moreover, the impact of physical activity on cognitive processes may also vary across different age groups and cultures. For instance, the developmental stage of children and adolescents means their cognitive responses to physical activity could differ significantly from those of adults. Cultural factors, such as differing attitudes towards physical activity, varying types of preferred exercises, and distinct societal norms regarding education and behaviors, may also influence how physical activity affects creative thinking in various populations. For example, activities like dance may have different cognitive implications in cultures where dance is a significant part of tradition and daily life, compared to cultures where it is less emphasized. Likewise, in cultures where educational systems and society emphasize collectivism, appropriateness, and conventional problem-solving, the patterns and outcomes of creative thinking might differ from those in cultures that encourage originality and independent thought [34].

Extending research to adolescents, who are navigating a pivotal period of cognitive and physical development, could yield valuable insights into the role of physical activity in academic and creative capacities. Similarly, studies focusing on the working population could explore how physical activity might enhance job-related cognitive functions, such as problem-solving under pressure or creative thinking in dynamic work environments. For the elderly, research might focus on how physical activity can mitigate age-related cognitive decline and maintain or even improve quality of life.

Therefore, future studies should strive to include a broader range of age groups and socio-demographic backgrounds, taking into account cultural variations. This approach would not only enrich our understanding of the cognitive benefits of physical activity but also aid in the development of targeted, age-appropriate, and culturally sensitive exercise programs designed to optimize cognitive health across the lifespan.

4.3 Cognitive mechanisms

While specific studies directly investigating the precise mechanism by which acute physical activity benefits creative thinking are yet to be conducted, hypothesized mechanisms for the cognitive benefits of physical activity are likely to apply here as well. Drawing from studies on broader cognitive functions and creativity, below we propose several potential cognitive mechanisms through which acute physical activity might stimulate creative thinking.

We noted earlier that divergent thinking is underpinned by associative abilities and cognitive flexibility [6, 11, 45]. Studies indicate that physical activity may enhance the retrieval of associative memories. For example, Pontifex et al. [104] observed that natural bouts of moderate-to-vigorous physical activities are linked with improved retrieval of paired-associate items. Similarly, Dongen et al. [121] reported that 35 min of vigorous physical activities (up to 80% HRmax) enhance recall of picture-location associations.

Furthermore, physical activity seems to improve cognitive flexibility, a component of executive functions. Oberste et al. [95] reviewed 22 studies and found overall beneficial effects of exercise on set shifting (g = 0.32). Interestingly, the effect of aerobic exercise was comparable to resistance exercise (g = 0.32 versus 0.30), with light intensity exercise showing a larger effect (g = 0.51) compared to moderate (0.24) or vigorous intensities (g = 0.13). Set shifting, or task switching, involves the capacity to alternate between tasks or mental sets and is crucial for representational flexibility [35, 39, 85]. This shifting ability may be crucial when it becomes necessary to discard unproductive strategies and rapidly transition to new, more promising approaches. Such flexibility enables exploration of previously unconsidered parts of the solution space, thereby facilitating divergent thinking. The finding that lower intensity exercise has the most substantial impact aligns with our observation that natural walking consistently enhances divergent thinking.

However, it is important to note that in our review, physical activities at low intensities did not significantly impact divergent thinking [21, 36, 52, 53]. These studies primarily used cycling or treadmill walking as interventions, where the manner of exercise, including speed and intensity, was predetermined. This contrasts with free walking, where the participants themselves largely determine the manner of walking. This element of 'freedom' in walking may be crucial for enhancing divergent thinking. On one hand, this unstructured nature of free walking may remove cognitive constraints, thereby promoting the emergence of unconventional and original solutions. On the other hand, it allows for mind wandering, a mental state known to bolster divergent thinking [2, 9, 125]. For example, Baird et al. [9] found that engaging in undemanding tasks that facilitate mind wandering enhances performance on divergent thinking tasks like the AUT. Consistently, Zhou et al. [128] discovered that free, unconstrained walking boosts divergent thinking more than walking with constraints (along an 8-shaped path). In contrast, activities like cycling or treadmill walking at predetermined low intensities, which require focused attention and top-down control, might interfere with the benefits of physical activity for creative thinking. As physical activity intensity increases, so might various executive functions, potentially leading to improved cognitive control and, consequently, the emergence of the divergent thinking-enhancing effects of physical activity at moderate intensities.

In the case of convergent thinking, it is more reliant on working memory [45, 55, 75]. Given its crucial role in actively maintaining information amidst the challenges of concurrent information processing and interference [38], working memory contributes significantly to fluid intelligence, accounting for more than half of its variance [67, 94]. In convergent thinking, working memory is essential for processing and integrating multiple information streams simultaneously. This capability is crucial for synthesizing diverse ideas or concepts, which is fundamental to the problem-solving processes typical of convergent thinking. Furthermore, working memory is key for sequential processing, ensuring a logical progression of thoughts and actions in problem-solving scenarios. It also plays a critical role in filtering irrelevant information, thereby focusing cognitive resources on relevant data and enhancing the efficiency of the thought process.

Our review corroborates the impact of physical activities, especially moderate-intensity aerobic exercise, on enhancing working memory [24, 76, 78]. This enhancement aligns with findings that moderate intensity physical activity improves convergent thinking [54], while lower [36, 52, 66] or maximal intensity activities [36] do not show the same effect. It also fits well with the inverted-U hypothesis for exercise-induced cognitive enhancements [81]. This suggests a nuanced relationship between the intensity of physical activity and its impact on the cognitive functions underpinning convergent thinking.

Another cognitive mechanism that may underlie the divergent thinking-enhancing effect of dance is the induction of flow states. Dance, with its inherent rhythmic nature and the challenge it presents, is not only a pleasurable activity but also a potent facilitator of the flow state [65]. The immersive and expressive qualities of dance align with Csikszentmihalyi’s [42] criteria for activities that induce flow—a state characterized by deep mental engagement and focused attention. This state is conducive to creative thinking, as it fosters an open and associative state of mind, reducing inhibitions and encouraging novel connections and ideas [47, 116]. Future research could delve deeper into understanding how flow states elicited by dance contribute to enhancing divergent thinking.

4.4 Neurobiological mechanisms

Exploring the neurobiological mechanisms underlying the effects of acute physical activity on creative thinking is essential. However, to date, there have been no studies directly employing neuroimaging or biological measures to assess these effects. Below, we draw evidence from broader research on general cognitive functions and propose several potential pathways that may explain how acute physical activity influences creative thinking at the neurobiological level. Our discussion aims to shed light on these underlying processes and pave the way for future research in this promising yet under-explored area.

Physical activity has been shown to enhance brain function through several key mechanisms. One of the most well-documented is the increase in neurotrophic factors, such as Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), which plays a crucial role in synaptic plasticity underlying learning and memory [28, 102]. The optimal timing for BDNF response to acute physical activity varies. A recent meta-analysis suggests a 30-min threshold for maximal BDNF elevation [46], although shorter durations as brief as six minutes might still yield significant increases [122]. Additionally, there appears to be a dose–response relationship between exercise intensity and BDNF concentrations [28, 102], indicating that milder activities like natural walking may not significantly increase BDNF [86].

Beyond BDNF, endocannabinoids, known for their role in exercise-induced euphoria [29], also contribute to the cognitive benefits of physical activity. These substances are believed to mediate the memory-enhancing effects of exercise [18, 50]. However, low intensity activities, including walking, do not appear to significantly alter endocannabinoid levels [44]. This suggests that while BDNF and endocannabinoids may be involved in the cognitive benefits of moderate to vigorous activities, other mechanisms might be at play for less intense exercises like walking.

Enhanced cerebral blood flow, which can be initiated within seconds by mild to vigorous physical activity, is another crucial mechanism [23, 89, 96]. This increased blood flow delivers more oxygen and nutrients to the brain, thereby facilitating better cognitive functioning. Specifically, the prefrontal cortex, a key area for creative thinking, benefits greatly from this increased blood flow [71, 89, 101]. Notably, even mild activities such as walking can enhance cerebral blood flow, possibly explaining their positive effects on creative thinking. For instance, a study by Byun et al. [20] demonstrated that just 10 min of very light cycling at 30% V̇O2peak increased blood flow in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and improved inhibitory control as evaluated by a color-word matching Stroop task. Similarly, Suwabe et al. [118] found that the same duration and intensity of cycling enhanced the functional connectivity between hippocampal dentate gyrus/CA3 and various cortical regions, the degree of which was correlated with improved pattern separation—a key aspect of cognitive flexibility [5]. At the molecular level, enhanced cerebral blood flow may be partly attributed to acetylcholine release. Even mild-intensity walking increases acetylcholine release in the cerebral cortex [73] and hippocampus [91]. Elevated acetylcholine levels in these regions have been linked to improved cognitive flexibility in animal models [68, 105]. However, it is also important to consider that prolonged or overly intense exercise can decrease cerebral blood flow, potentially leading to central fatigue [96] and impairing certain cognitive functions, such as convergent thinking [36].

Another central mechanism potentially explaining the enhancement of divergent thinking through walking and more intense activities could be attributed to the release of dopamine in the brain. This neurotransmitter is liberated in multiple regions, including the striatum, the prefrontal cortex, and the hippocampus [10, 30, 31, 56, 84]. It plays a vital role in initiating movement [51]. Moreover, simple repetitive actions such as moving the upper limb [79] or flexing a foot at the ankle [99] have been found to activate dopamine neurons, leading to dopamine release. Considering dopamine’s significant contribution to cognitive flexibility [70, 106], its release during physical activities like walking could be an essential factor in facilitating divergent thinking.

These neurobiological mechanisms have been summarized in Fig. 1.

On the other hand, dance, varying in style and pace, can range from moderate to vigorous in intensity. More than just a physical activity, dance is a cognitively engaging exercise [28] often paired with music and demanding coordination and rhythm. This form of exercise extensively stimulates the brain, activating multiple areas related to somatosensory processing, motor functions, and cognitive abilities [119]. Such comprehensive brain engagement may contribute to the enhancement of creative capacities.

5 Concluding remarks

Recognizing the critical importance of creative thinking, it becomes essential to delve deeply into how different physical activities and their intensities affect creative cognition. This knowledge is not only academically enriching but also has practical implications for crafting targeted strategies that leverage physical activity for cognitive and creative enhancement in everyday life. One key finding of this comprehensive narrative review is the enhancement of divergent thinking by walking at a natural pace. Moreover, although based on limited studies, moderate intensity aerobic exercise and dance may also promote divergent thinking. In addition, engaging in vigorous intensity aerobic exercise seems to enhance secondary aspects of divergent thinking, in terms of the quantity and flexibility of idea generation.

The need for a more comprehensive exploration of this topic is clear and could have significant implications for exercise and cognitive psychology. Research into how various intensities and types of physical activity distinctively impact cognition represents a crucial frontier in exercise psychology. While prior studies have primarily concentrated on the fundamental aspects of cognition, extending this investigation to encompass the influence on creativity could yield vital insights into higher-level cognitive functions. Such an exploration stands to not only deepen our theoretical understanding but also offer substantial practical applications. The role of mood enhancement, frequently a consequence of physical activity, has garnered significant interest in this context. Mood fluctuations are often correlated with creative capacities, yet the precise mechanisms by which these changes in mood interact with creative cognition are not fully understood. Unraveling this relationship may provide critical insights into the broader field of exercise psychology.

Furthermore, examining the cognitive mechanisms at the intersection of physical activity and creativity promises to make substantial contributions to cognitive psychology. Investigating this link may reveal new insights into the cognitive underpinnings of creativity. It could also clarify how creativity is associated with fundamental executive functions, mind wandering, and flow. This approach not only seeks to expand our theoretical knowledge but also to inform practical strategies in educational and professional settings where creative problem-solving and innovation are increasingly valued.

Our review sets the stage for future investigations that will further elucidate the complex dynamics between physical activity and creative thinking. This exploration promises to inform educators and individuals about optimizing physical activity regimes for cognitive and creative enhancement, contributing to personal and professional growth in our complex and dynamic world.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Aga K, Inamura M, Chen C, Hagiwara K, Yamashita R, Hirotsu M, Nakagawa S. The effect of acute aerobic exercise on divergent and convergent thinking and its influence by mood. Brain Sci. 2021;11(5):546.

Agnoli S, Vanucci M, Pelagatti C, Corazza GE. Exploring the link between mind wandering, mindfulness, and creativity: a multidimensional approach. Creat Res J. 2018;30(1):41–53.

Amabile TM, Barsade SG, Mueller JS, Staw BM. Affect and creativity at work. Adm Sci Q. 2005;50(3):367–403.

American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Eleventh. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2022.

Anacker C, Hen R. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis and cognitive flexibility—linking memory and mood. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18(6):335–46.

Arán Filippetti V, Krumm G. A hierarchical model of cognitive flexibility in children: extending the relationship between flexibility, creativity and academic achievement. Child Neuropsychol. 2020;26(6):770–800.

Atchley RA, Strayer DL, Atchley P. Creativity in the wild: improving creative reasoning through immersion in natural settings. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):e51474.

Baas M, De Dreu CK, Nijstad BA. A meta-analysis of 25 years of mood-creativity research: hedonic tone, activation, or regulatory focus? Psychol Bull. 2008;134(6):779.

Baird B, Smallwood J, Mrazek MD, Kam JW, Franklin MS, Schooler JW. Inspired by distraction: mind wandering facilitates creative incubation. Psychol Sci. 2012;23(10):1117–22.

Bastioli G, Arnold JC, Mancini M, Mar AC, Gamallo-Lana B, Saadipour K, Rice ME. Voluntary exercise boosts striatal dopamine release: evidence for the necessary and sufficient role of BDNF. J Neurosci. 2022;42(23):4725–36.

Benedek M, Könen T, Neubauer AC. Associative abilities underlying creativity. Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts. 2012;6(3):273.

Blanchette DM, Ramocki SP, O’del, J. N., & Casey, M. S. Aerobic exercise and creative potential: immediate and residual effects. Creat Res J. 2005;17(2–3):257–64.

Bollimbala A, James PS, Ganguli S. Impact of acute physical activity on children’s divergent and convergent thinking: the mediating role of a low body mass index. Percept Mot Skills. 2019;126(4):603–22.

Bollimbala A, James PS, Ganguli S. The effect of Hatha yoga intervention on students’ creative ability. Acta Physiol. 2020;209:103121.

Bollimbala A, James PS, Ganguli S. Impact of physical activity on an individual’s creativity: a day-level analysis. Am J Psychol. 2021;134(1):93–105.

Bollimbala A, James PS, Ganguli S. Grooving, moving, and stretching out of the box! The role of recovery experiences in the relation between physical activity and creativity. Personality Individ Differ. 2022;196:111757.

Bollimbala A, James PS, Ganguli S. The impact of physical activity intervention on creativity: role of flexibility vs persistence pathways. Think Skills Creat. 2023;49:101313.

Bosch BM, Bringard A, Logrieco MG, Lauer E, Imobersteg N, Thomas A, Igloi K. A single session of moderate intensity exercise influences memory, endocannabinoids and brain derived neurotrophic factor levels in men. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):14371.

Bowden EM, Jung-Beeman M. Normative data for 144 compound remote associate problems. Behav Res Methods, Instrum, Comput. 2003;35:634–9.

Byun K, Hyodo K, Suwabe K, Ochi G, Sakairi Y, Kato M, Soya H. Positive effect of acute mild exercise on executive function via arousal-related prefrontal activations: an fNIRS study. Neuroimage. 2014;98:336–45.

Campion M, Levita L. Enhancing positive affect and divergent thinking abilities: play some music and dance. J Posit Psychol. 2014;9(2):137–45.

Cantelon JA, Giles GE. A review of cognitive changes during acute aerobic exercise. Front Psychol. 2021;12:653158.

Carter SE, Draijer R, Holder SM, Brown L, Thijssen DH, Hopkins ND. Regular walking breaks prevent the decline in cerebral blood flow associated with prolonged sitting. J Appl Physiol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00310.2018.

Chang YK, Labban JD, Gapin JI, Etnier JL. The effects of acute exercise on cognitive performance: a meta-analysis. Brain Res. 2012;1453:87–101.

Chen C. Fitness powered brains. London, UK: Brain & Life Publishing; 2017.

Chen C. Plato’s Insight: how physical exercise boosts mental excellence. London, UK: Brain & Life Publishing; 2017.

Chen C, Mochizuki Y, Hagiwara K, Hirotsu M, Nakagawa S. Regular vigorous-intensity physical activity and walking are associated with divergent but not convergent thinking in Japanese young adults. Brain Sci. 2021;11(8):1046.

Chen C, Nakagawa S. Physical activity for cognitive health promotion: an overview of the underlying neurobiological mechanisms. Ageing Res Rev. 2023;86:101868.

Chen C, Nakagawa S. Recent advances in the study of the neurobiological mechanisms behind the effects of physical activity on mood, resilience and emotional disorders. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2023;32(9):937–42.

Chen C, Nakagawa S, Kitaichi Y, An Y, Omiya Y, Song N, Kusumi I. The role of medial prefrontal corticosterone and dopamine in the antidepressant-like effect of exercise. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;69:1–9.

Chen C, Nakagawa S, An Y, Ito K, Kitaichi Y, Kusumi I. The exercise-glucocorticoid paradox: how exercise is beneficial to cognition, mood, and the brain while increasing glucocorticoid levels. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2017;44:83–102.

Chen C, Okubo R, Hagiwara K, Mizumoto T, Nakagawa S, Tabuchi T. The association of positive emotions with absenteeism and presenteeism in Japanese workers. J Affect Disord. 2024;344:319–24.

Chen C, Yau SY, Clemente FM, Ishihara T. The effects of physical activity and exercise on cognitive and affective wellbeing. Lausanne: Frontiers Media SA; 2022.

Chen J, Shi B, Chen Q, Qiu J. Comparisons of convergent thinking: a perspective informed by culture and neural mechanisms. Think Skills Creat. 2023;49:101343.

Chrysikou EG. Creativity in and out of (cognitive) control. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2019;27:94–9.

Colzato LS, Szapora Ozturk A, Pannekoek JN, Hommel B. The impact of physical exercise on convergent and divergent thinking. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:824.

Conner TS, Silvia PJ. Creative days: a daily diary study of emotion, personality, and everyday creativity. Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts. 2015;9(4):463–70.

Conway AR, Kane MJ, Engle RW. Working memory capacity and its relation to general intelligence. Trends Cogn Sci. 2003;7(12):547–52.

Cools R, Barker RA, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW. Mechanisms of cognitive set flexibility in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2001;124(12):2503–12.

Cropley AJ. Defining and measuring creativity: are creativity tests worth using? Roeper Rev. 2000;23(2):72–9.

Cropley A. In praise of convergent thinking. Creat Res J. 2006;18(3):391–404.

Csikzentimihalyi M. Beyond boredom and anxiety: experiencing flow in work and play. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1975.

Davis MA. Understanding the relationship between mood and creativity: a meta-analysis. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2009;108(1):25–38.

Desai S, Borg B, Cuttler C, Crombie KM, Rabinak CA, Hill MN, Marusak HA. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of exercise on the endocannabinoid system. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2022;7(4):388–408.

Diamond A. Executive functions. Annu Rev Psychol. 2013;64:135–68.

Dinoff A, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Lanctot KL. The effect of acute exercise on blood concentrations of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in healthy adults: a meta-analysis. Eur J Neurosci. 2017;46(1):1635–46.

Dou X, Li H, Jia L. The linkage cultivation of creative thinking and innovative thinking in dance choreography. Think Skills Creat. 2021;41:100896.

Eskine KE, Anderson AE, Sullivan M, Golob EJ. Effects of music listening on creative cognition and semantic memory retrieval. Psychol Music. 2020;48(4):513–28.

de Fernandes M, Sousa A, Medeiros AR, Del Rosso S, Stults-Kolehmainen M, Boullosa DA. The influence of exercise and physical fitness status on attention: a systematic review. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. 2019;12(1):202–34.

Ferreira-Vieira TH, Bastos CP, Pereira GS, Moreira FA, Massensini AR. A role for the endocannabinoid system in exercise-induced spatial memory enhancement in mice. Hippocampus. 2014;24(1):79–88.

Foley TE, Fleshner M. Neuroplasticity of dopamine circuits after exercise: implications for central fatigue. NeuroMol Med. 2008;10:67–80.

Frith E, Loprinzi PD. Experimental effects of acute exercise and music listening on cognitive creativity. Physiol Behav. 2018;191:21–8.

Frith E, Ponce P, Loprinzi PD. Active or inert? An experimental comparison of creative ideation across incubation periods. J Creat Behavior. 2021;55(1):5–14.

Frith E, Miller SE, Loprinzi PD. Effects of verbal priming with acute exercise on convergent creativity. Psychol Rep. 2022;125(1):375–97.

Gerver CR, Griffin JW, Dennis NA, Beaty RE. Memory and creativity: a meta-analytic examination of the relationship between memory systems and creative cognition. Psychon Bull Rev. 2023;30:2116–2154.

Goekint M, Bos I, Heyman E, Meeusen R, Michotte Y, Sarre S. Acute running stimulates hippocampal dopaminergic neurotransmission in rats, but has no influence on brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Appl Physiol. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00306.2011.

Gralewski J, Karwowski M. Are teachers’ ratings of students’ creativity related to students’ divergent thinking? A meta-analysis. Think Skills Creat. 2019;33:100583.

Gube M, Lajoie S. Adaptive expertise and creative thinking: a synthetic review and implications for practice. Think Skills Creat. 2020;35:100630.

Guilford JP. Creativity. Am Psychol. 1950;5:444–54.

Guilford JP. Alternate uses, form a. Beverly Hills: Sheridan Supply; 1960.

Guilford JP. Creativity, intelligence, and their educational implications. San Diego: EDITS/Knapp; 1968.

Huang TY, Chen FT, Li RH, Hillman CH, Cline TL, Chu CH, Chang YK. Effects of acute resistance exercise on executive function: a systematic review of the moderating role of intensity and executive function domain. Sports Med-Open. 2022;8(1):1–13.

Isen AM, Daubman KA, Nowicki GP. Positive affect facilitates creative problem solving. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;52(6):1122–31.

Ishihara T, Drollette ES, Ludyga S, Hillman CH, Kamijo K. The effects of acute aerobic exercise on executive function: A systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;128:258–69.

Jaque SV, Thomson P, Zaragoza J, Werner F, Podeszwa J, Jacobs K. Creative flow and physiologic states in dancers during performance. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1000.

Jung M, Frith E, Kang M, Loprinzi PD. Effects of acute exercise on verbal, mathematical, and spatial insight creativity. J Sci Sport Exercise. 2023;5(1):87–96.

Kane MJ, Hambrick DZ, Conway ARA. Working memory capacity and fluid intelligence are strongly related constructs: comment on Ackerman, Beier, and Boyle (2005). Psychol Bull. 2005;131(1):66–71.

Karvat G, Kimchi T. Acetylcholine elevation relieves cognitive rigidity and social deficiency in a mouse model of autism. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(4):831–40.

Kaufman JC, Sternberg RJ. The Cambridge handbook of creativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2019.

Klanker M, Feenstra M, Denys D. Dopaminergic control of cognitive flexibility in humans and animals. Front Neurosci. 2013;7:201.

Kleibeuker SW, Koolschijn PCM, Jolles DD, Schel MA, De Dreu CK, Crone EA. Prefrontal cortex involvement in creative problem solving in middle adolescence and adulthood. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2013;5:197–206.

Knoblich G, Ohlsson S, Haider H, Rhenius D. Constraint relaxation and chunk decomposition in insight problem solving. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 1999;25(6):1534.

Kurosawa M, Okada K, Sato A, Uchida S. Extracellular release of acetylcholine, noradrenaline and serotonin increases in the cerebral cortex during walking in conscious rats. Neurosci Lett. 1993;161(1):73–6.

Lambourne K, Tomporowski P. The effect of exercise-induced arousal on cognitive task performance: a meta-regression analysis. Brain Res. 2010;1341:12–24.

Lee CS, Therriault DJ. The cognitive underpinnings of creative thought: a latent variable analysis exploring the roles of intelligence and working memory in three creative thinking processes. Intelligence. 2013;41(5):306–20.

Liu S, Yu Q, Li Z, Cunha PM, Zhang Y, Kong Z, Cai Y. Effects of acute and chronic exercises on executive function in children and adolescents: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2020;11:554915.

Loprinzi PD, Blough J, Crawford L, Ryu S, Zou L, Li H. The temporal effects of acute exercise on episodic memory function: Systematic review with meta-analysis. Brain Sci. 2019;9(4):87.

Ludyga S, Gerber M, Brand S, Holsboer-Trachsler E, Pühse U. Acute effects of moderate aerobic exercise on specific aspects of executive function in different age and fitness groups: a meta-analysis. Psychophysiology. 2016;53(11):1611–26.

Magariños-Ascone C, Buño W, García-Austt E. Activity in monkey substantia nigra neurons related to a simple learned movement. Exp Brain Res. 1992;88:283–91.

Matsumoto K, Chen C, Hagiwara K, Shimizu N, Hirotsu M, Oda Y, Nakagawa S. The effect of brief stair-climbing on divergent and convergent thinking. Front Behav Neurosci. 2022;15:834097.

McMorris T, Hale BJ. Differential effects of differing intensities of acute exercise on speed and accuracy of cognition: a meta-analytical investigation. Brain Cogn. 2012;80(3):338–51.

Mednick SA. The associative basis of the creative process. Psychol Rev. 1962;69:220–32.

Mednick MT, Mednick SA, Mednick EV. Incubation of creative performance and specific associative priming. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 1964;69(1):84.

Meeusen R, Piacentini MF, Meirleir KD. Brain microdialysis in exercise research. Sports Med. 2001;31:965–83.

Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, Wager TD. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: a latent variable analysis. Cogn Psychol. 2000;41(1):49–100.

Morais VACD, Tourino MFDS, Almeida ACDS, Albuquerque TBD, Linhares RC, Christo PP, Scalzo PL. A single session of moderate intensity walking increases brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the chronic post-stroke patients. Top Stroke Rehabilit. 2018;25(1):1–5.

Moreau D, Chou E. The acute effect of high-intensity exercise on executive function: a meta-analysis. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2019;14(5):734–64.

Murali S, Händel B. Motor restrictions impair divergent thinking during walking and during sitting. Psychol Res. 2022;86(7):2144–57.

Mulser L, Moreau D. Effect of acute cardiovascular exercise on cerebral blood flow: a systematic review. Brain Res. 2023;1809:148355.

Nakagawa T, Koan I, Chen C, Matsubara T, Hagiwara K, Lei H, Nakagawa S. Regular moderate-to vigorous-intensity physical activity rather than walking is associated with enhanced cognitive functions and mental health in young adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(2):614.

Nakajima K, Uchida S, Suzuki A, Hotta H, Aikawa Y. The effect of walking on regional blood flow and acetylcholine in the hippocampus in conscious rats. Auton Neurosci. 2003;103(1–2):83–92.

Netz Y, Tomer R, Axelrad S, Argov E, Inbar O. The effect of a single aerobic training session on cognitive flexibility in late middle-aged adults. Int J Sports Med. 2007;28(01):82–7.

Newton DP. Moods, emotions and creative thinking: a framework for teaching. Think Skills Creat. 2013;8:34–44.

Oberauer K, Schulze R, Wilhelm O, Süß H-M. Working memory and intelligence-their correlation and their relation: comment on Ackerman, Beier, and Boyle (2005). Psychol Bull. 2005;131(1):61–5.

Oberste M, Sharma S, Bloch W, Zimmer P. Acute exercise-induced set shifting benefits in healthy adults and its moderators: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2021;12:528352.

Ogoh S, Ainslie PN. Cerebral blood flow during exercise: mechanisms of regulation. J Appl Physiol. 2009;107(5):1370–80.

Oppezzo M, Schwartz DL. Give your ideas some legs: the positive effect of walking on creative thinking. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 2014;40(4):1142.

Österberg P, Olsson BK. Dancing: a strategy to maintain schoolchildren’s openness for idea generation. J Phys Educ Recreat Dance. 2021;92(3):20–5.

Ouchi Y, Yoshikawa E, Futatsubashi M, Okada H, Torizuka T, Sakamoto M. Effect of simple motor performance on regional dopamine release in the striatum in Parkinson disease patients and healthy subjects: a positron emission tomography study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22(6):746–52.

Parke MR, Seo M-G, Sherf EN. Regulating and facilitating: the role of emotional intelligence in maintaining and using positive affect for creativity. J Appl Psychol. 2015;100(3):917–34.

Peña J, Sampedro A, Ibarretxe-Bilbao N, Zubiaurre-Elorza L, Ojeda N. Improvement in creativity after transcranial random noise stimulation (tRNS) over the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):7116.

Piepmeier AT, Etnier JL. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) as a potential mechanism of the effects of acute exercise on cognitive performance. J Sport Health Sci. 2015;4(1):14–23.

Plucker JA. Is the proof in the pudding? Re-analyses of Torrance’s (1958 to Present) longitudinal data. Creat Res J. 1999;12:103–14.

Pontifex MB, Gwizdala KL, Parks AC, Pfeiffer KA, Fenn KM. The association between physical activity during the day and long-term memory stability. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):38148.

Prado VF, Janickova H, Al-Onaizi MA, Prado MA. Cholinergic circuits in cognitive flexibility. Neuroscience. 2017;345:130–41.

Radke AK, Kocharian A, Covey DP, Lovinger DM, Cheer JF, Mateo Y, Holmes A. Contributions of nucleus accumbens dopamine to cognitive flexibility. Eur J Neurosci. 2019;50(3):2023–35.

Ratey JJ. Spark: the revolutionary new science of exercise and the brain. London: Hachette UK; 2008.

Ritter SM, Ferguson S. Happy creativity: listening to happy music facilitates divergent thinking. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(9):e0182210.

Roig M, Nordbrandt S, Geertsen SS, Nielsen JB. The effects of cardiovascular exercise on human memory: a review with meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37(8):1645–66.

Román PÁL, Vallejo AP, Aguayo BB. Acute aerobic exercise enhances students’ creativity. Creat Res J. 2018;30(3):310–5.

Rominger C, Schneider M, Fink A, Tran US, Perchtold-Stefan CM, Schwerdtfeger AR. Acute and chronic physical activity increases creative ideation performance: a systematic review and multilevel meta-analysis. Sports Med-Open. 2022;8(1):1–17.

Runco MA, Acar S. Divergent thinking as an indicator of creative potential. Creat Res J. 2012;24(1):66–75.

Runco MA, Acar S. Divergent thinking. In: Kaufman JC, Sternberg RJ, editors. The Cambridge handbook of creativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2019. p. 224–54.

Runco MA, Millar G, Acar S, Cramond B. Torrance tests of creative thinking as predictors of personal and public achievement: a fifty-year follow-up. Creat Res J. 2010;22(4):361–8.

Sawyer RK. Explaining creativity: the science of human innovation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012.

Schutte NS, Malouff JM. Connections between curiosity, flow and creativity. Personality Individ Differ. 2020;152:109555.

Steinberg H, Sykes EA, Moss T, Lowery S, LeBoutillier N, Dewey A. Exercise enhances creativity independently of mood. Br J Sports Med. 1997;31(3):240–5.

Suwabe K, Byun K, Hyodo K, Reagh ZM, Roberts JM, Matsushita A, Soya H. Rapid stimulation of human dentate gyrus function with acute mild exercise. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115(41):10487–92.

Teixeira-Machado L, Arida RM, de Jesus Mari J. Dance for neuroplasticity: a descriptive systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;96:232–40.

Torrance EP. Torrance tests of creative thinking: norms technical manual. Research. Princeton: Personnel Press; 1966.

van Dongen EV, Kersten IH, Wagner IC, Morris RG, Fernández G. Physical exercise performed four hours after learning improves memory retention and increases hippocampal pattern similarity during retrieval. Curr Biol. 2016;26(13):1722–7.

Walsh EI, Smith L, Northey J, Rattray B, Cherbuin N. Towards an understanding of the physical activity-BDNF-cognition triumvirate: a review of associations and dosage. Ageing Res Rev. 2020;60:101044.

Wanner P, Cheng FH, Steib S. Effects of acute cardiovascular exercise on motor memory encoding and consolidation: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;116:365–81.

Weisberg RW. Creativity: understanding innovation in problem solving, science, invention, and the arts. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2006.

Yamaoka A, Yukawa S. Mind wandering in creative problem-solving: relationships with divergent thinking and mental health. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0231946.

Yamashita R, Chen C, Matsubara T, Hagiwara K, Inamura M, Aga K, Nakagawa S. The mood-improving effect of viewing images of nature and its neural substrate. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5500.

Yeh CW, Hung SH, Chang CY. The influence of natural environments on creativity. Front Psych. 2022;13:895213.

Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Hommel B, Zhang H. The impact of bodily states on divergent thinking: evidence for a control-depletion account. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1546.

Funding

This research was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (Grant Number JP 22K15764) and a grant from The Nakatomi Foundation to C.C. The findings of this article do not represent the official views of the research funders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Manuscript preparation & review: CC.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

C.C. is the author of two books, Fitness Powered Brains and Plato's Insight.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, C. Exploring the impact of acute physical activity on creative thinking: a comprehensive narrative review with a focus on activity type and intensity. Discov Psychol 4, 3 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-024-00114-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-024-00114-9