Abstract

During coke production, large volume of effluent is generated, which has a very complex chemical composition and contains several toxic and carcinogenic substances, mainly aromatic compounds, cyanide, thiocyanate and ammonium. The composition of these high-strength effluents is very diverse and depends on the quality of coals used and the operating and technological parameters of coke ovens. In general, after initial physicochemical treatment, biological purification steps are applied in activated sludge bioreactors. This review summarizes the current knowledge on the anaerobic and aerobic transformation processes and describes key microorganisms, such as phenol- and thiocyanate-degrading, floc-forming, nitrifying and denitrifying bacteria, which contribute to the removal of pollutants from coke plant effluents. Providing the theoretical basis for technical issues (in this case the microbiology of coke plant effluent treatment) aids the optimization of existing technologies and the design of new management techniques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the last decade, global steel demand has kept on growing, leading to a record of 1870 million tons of crude steel production in 2019, which means more than doubling of production in the last 20 years (World Steel Association 2020). Despite the development of alternative ironmaking technologies (Hasanbeigi et al. 2014), more than 70% of crude steel produced worldwide is still manufactured via the blast furnace-basic oxygen furnace route which uses coal to reduce iron oxides in the ores and to generate heat for smelting (World Coal Association 2020). To achieve the purity required for steel making, coal has to be converted into coke. During the coking process, coal is heated to around 1000 °C in the absence of oxygen to drive off the volatile compounds. The resulting coke is a hard porous material composed of almost pure carbon. Hot coke is usually quenched with water, and the gases containing the volatilized materials are also washed with water resulting in the coking wastewater, which is also referred as coke oven wastewater, coal gasification wastewater or coke plant effluent (Kwiecińska et al. 2017; Nowak et al. 2004).

These effluents are high-strength wastewaters, which (in order to accomplish environmental regulations) have to undergo intensive purification processes prior to their discharge; therefore, steel industry has developed a plethora of methods for the treatment of coking effluents (Tong et al. 2018). Various techniques available combine different physical, chemical and biological processes, and the biological unit is an almost indispensable part of a successful and cost-effective treatment process (Zhao and Liu 2016; Zhu et al. 2018). In general, up to 90–99% reduction in contaminants can be achieved (Kim et al. 2008a; Maiti et al. 2019; Tong et al. 2018; Zhu et al. 2018).

Although information available on the structure and function of microbial communities in wastewater treatment processes increased considerably in the past decades, most of the studies were conducted on municipal (i.e., domestic) wastewaters (Cydzik-Kwiatkowska and Zielińska 2016; Wu et al. 2019), and research focusing on the background of microbial processes during the treatment of coke plant effluents is still limited. Furthermore, recent reviews (Kwiecińska et al. 2017; Maiti et al. 2019; Zhao and Liu 2016; Zhu et al. 2018) on coking wastewater treatment focus mainly on the technological aspects of different purification strategies, while microbiological findings (e.g., those that were obtained with high-throughput DNA sequencing methods during the last years) have not been considered. Therefore, the major aim of this review is to summarize the current knowledge on microbiological processes related to coke plant effluent treatment, which could help the optimization of available technologies and aid the design of new management techniques.

Composition of coke plant effluents

In addition to the aqueous material obtained with distillation during the coking process, quenching of hot coke generates effluent with high suspended matter, while washing the produced gas results in a toxic liquid with high concentration of nitrogenous compounds and cyclic organic molecules (Ghose 2002; Kwiecińska et al. 2017). Some of these compounds are volatile under the conditions present in raw wastewater (Kjeldsen 1999; Zhu et al. 2018); therefore, a direct exposure to such liquids constitutes a serious risk to human health. The composition of coke plant effluents depends mainly on the quality of coals used and the operating and technological parameters of coke ovens (Maiti et al. 2019; Zhu et al. 2018) (Table 1).

Organic pollutants

There is a huge diversity of organic molecules present in raw coke plant effluents with varying quantity and composition (Li et al. 2003; Lu et al. 2009; Zhao and Liu 2016; Zhu et al. 2018). Additionally, most of these molecules are carcinogenic and toxic, and as a consequence in mammals, they may cause gastrointestinal disorders, kidney and liver damage, lung hemorrhages, diverse neurological symptoms and finally death (Padoley et al. 2008).

The most abundant organic substances are aromatic compounds such as phenolic compounds (around 40–50% of total COD) including phenol, cresols (methylphenoles), di- and trimethylphenols (Li et al. 2003; Lu et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 1998; Zhao and Liu 2016). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs, e.g., naphthalene) are molecules that contain fused aromatic rings with no heteroatoms or substituents. Concentration of PAHs is usually low compared to the other organic pollutants present in raw effluents (Li et al. 2003). Regarding nitrogen heterocyclic compounds (NHCs), pyridine, quinoline, isoquinoline, indole and their derivatives are the most common (Li et al. 2003; Padoley et al. 2008). NHCs could contribute up to 30-50% of total organic content in raw wastewater (Li et al. 2003; Zhang et al. 1998; Zhu et al. 2018). In smaller amounts, even sulfur containing organics and long-chain n-alkanes may be present (Li et al. 2003; Zhao and Liu 2016). Certain organic molecules (e.g., some alkylated pyridines and PAHs) are less biodegradable and persist in the biological purification, resulting in relatively high COD values in the treated effluent (Li et al. 2003; Stamoudis and Luthy 1980; Zhu et al. 2018) (Table 1); therefore, additional treatments (e.g., advanced oxidation) may be required before discharge to recipient waters (Ji et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2016; Zhu et al. 2018).

Tars may also present in significant amount in raw effluents (2–5%) that could be subsequently separated with physicochemical treatments (Kwiecińska et al. 2017).

Inorganic pollutants

The major inorganic compounds present in the coke plant effluent are cyanide (CN−), thiocyanate (SCN−), ammonium and sulfate (Table 1).

Cyanide ion is present in two forms, the less toxic complex cyanide that is combined with metals (especially with ferric ion) and the highly toxic free cyanide (Kjeldsen 1999; Kwiecińska et al. 2017). In its free form, cyanide binds to the heme iron in cytochrome oxidase and thereby blocks aerobic respiration (Shifrin et al. 1996). Therefore, cyanide is usually converted into thiocyanate with reduced sulfur species prior to biological treatment (Olson et al. 2003). Although thiocyanate has relatively lower toxicity compared to cyanide, it can also inhibit biodegradation processes (Neufeld and Valiknac 1979; Olson et al. 2003).

Ammonium is usually present in high amount in raw effluents, and its concentration could be reduced by physicochemical pre-treatments (Maranón et al. 2008), but in turn, it could be also produced during the biological treatment, via the decomposition of organic nitrogen compounds (the process called ammonification) or via the hydrolysis of thiocyanate (Hung and Pavlostathis 1997). Similarly, biological oxidation of the sulfur atom in thiocyanate under aerobic conditions leads to the increase in sulfate content in wastewater (Felföldi et al. 2010; Hung and Pavlostathis 1997) (Table 1; see also Eq. 5).

Physicochemical treatments for the reduction in toxicity

Several of the above-mentioned organic and inorganic compounds present in raw wastewater are toxic even to versatile microorganisms; therefore, prior to biological treatments physical and chemical processes are applied to reduce the concentration of such components. There is a huge variety of methods available for the physical removal (e.g., phenol extraction, ammonia stripping, tar separation, flotation, coagulation) or conversion of contaminants (e.g., conversion of cyanide to thiocyanate with reduced sulfur species, oxidation of heterocyclic compounds) (Chen et al. 2019; Kozak and Wlodarczyk-Makula 2018; Maiti et al. 2019; Ryu et al. 2009), but the detailed discussion of these processes is beyond the scope of this review and could be found elsewhere (e.g., Zhu et al. 2018). In addition to the above-mentioned physicochemical treatments, in some cases dilution (e.g., with municipal wastewater or by partial recirculation of purified effluent) is also used to reduce the concentration of toxic contaminants (Maiti et al. 2019; Maranón et al. 2008; Tong et al. 2018).

Bioreactor characteristics and operation

The efficiency of a single bioreactor or a reactor cascade depends on the chemical nature of the treated water and on operation characteristics, such as hydraulic retention time (HRT), temperature, sludge recirculation ratio, pH and dissolved oxygen content. All these parameters affect the activity and composition of the microorganisms which eventually perform the removal of contaminants (Kim et al. 2008a; Ma et al. 2015a; Rowan et al. 2003).

Major biological transformation processes in bioreactors

The biological treatment aims to remove ammonium, thiocyanate, phenols and many other organic compounds (i.e., reduction in COD) via aerobic and anaerobic transformation processes (Table 2). Microorganisms can use the organic and inorganic contaminants of the coke plant effluent as carbon or nitrogen sources or to gain energy, and as a result microbial biomass is produced and some gaseous compounds are released (mainly CO2 and in the case of denitrification N2). These processes are described in detail at the molecular level in the subsequent chapter.

From a microbiological point of view, supplying the proper amount of oxygen as electron acceptor for the aerobic oxidation is crucial. However, some processes may require the addition of chemicals, e.g., carbonate to adjust pH and as a carbon source for autotrophic nitrifying microorganisms in the nitrification reactors, sulfuric acid to lower pH in the denitrification reactor, methanol (or other simple organic compounds) as carbon source and electron donor for denitrification, and since coke plant effluents contain low amount of phosphorous, addition of inorganic phosphate as phosphorus source may also improve the performance of biological treatment (Felföldi et al. 2010; Kim et al. 2007, 2009; Li et al. 2003; Maranón et al. 2008; Raper et al. 2018a, 2019a; Zhu et al. 2015).

Operational characteristics and arrangement of bioreactors

Biological treatment of wastewaters could be carried out either using activated sludge or biofilm processes, and as it was mentioned above, bioreactor design, operational characteristics and technical parameters (e.g., temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen content, HRT, type and structure of biofilm carrier, sludge recirculation ratio) determine microbial community composition and activity, and therefore purification efficiency (Bitton 2011; Chen et al. 2017; Felföldi et al. 2015; Jurecska et al. 2013; Kim et al. 2008a; Ma et al. 2015a; Rowan et al. 2003). However, providing a detailed overview on reactor design, setup and other practical aspects are beyond the scope of this review and could be found elsewhere (e.g., Bitton 2011; Davis 2010), and in the case of coking wastewater it has been discussed in recent reviews (Ji et al. 2016; Tong et al. 2018; Zhu et al. 2018). It should be also noted that new technologies are emerging (e.g., activated carbon sludge processes, moving bed biofilm reactors, fluidized-bed bioreactors) to overcome problems related to the purification of these harsh wastewaters (see details in Zhu et al. 2018).

In general, complete biological treatment of coking wastewater is not possible in a single reactor, since some biological transformations require different operational characteristics (e.g., oxygen concentration and pH; Table 2). Therefore, contaminant removal is performed in sequential manner in order to achieve the specific effluent discharge limits (Tong et al. 2018). On the other hand, several pollutants, like phenols and thiocyanate, can be removed in a single-step process (Felföldi et al. 2010; Vázquez et al. 2006), since, e.g., the inhibitory effect of thiocyanate is relatively low on bacterial phenol degradation (Arutchelvan et al. 2005).

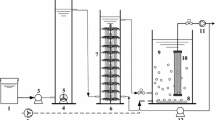

The previously common two-step [aerobic(oxic)–anaerobic or anoxic (O/A) or anoxic–oxic (A/O)] reactor cascades are nowadays being replaced with three [anaerobic–anoxic–oxic (A/A/O) or anaerobic–oxic–oxic (A/O/O)] or even four-step [anaerobic–anoxic–oxic–oxic (A/A/O/O) or anaerobic–oxic–anoxic–oxic (A/O/A/O)] reactor cascades (Ma et al. 2015a; Zhang et al. 2016; Zhu et al. 2018), since increasing the number of reactors usually increases the performance of the system (Ji et al. 2016; Zhao and Liu 2016). The major advantage of placing an anaerobic reaction in the beginning of the system is to lower the external carbon source demand of heterotrophic denitrifying bacteria and enhance the degradation of recalcitrant organics (Li et al. 2003; Maranón et al. 2008; Raper et al. 2019a; Zhang et al. 2012; Zhao and Liu 2016). On the other hand, anaerobic bacteria are very sensitive to the presence of toxic pollutants; therefore, the introduction of two-phase anaerobic systems has been suggested (Zhao and Liu 2016). Various other reactor cascades and setups were and are tested continuously at laboratory and pilot scale (e.g., Zhu et al. 2015; see also “Appendix”), and results obtained from such studies provide the basis of process optimization in plant scale systems through the scaling-up processes (Kim et al. 2009; Maiti et al. 2019).

Key microorganisms in bioreactors

The biological purification processes (biodegradation of organic compounds and thiocyanate, removal of nitrogen) in coke plant effluent-treating bioreactors are carried out primarily by bacteria (Table 3); however, fungi were also reported to perform some of the above-mentioned transformations. Recent advances in molecular biology (e.g., the introduction of high-throughput DNA sequencing methods) aided to decipher the detailed taxonomic structure of microbial communities in the bioreactors. Studies revealed that members of the phylum Proteobacteria are the most abundant microorganisms in the bioreactors, contribution of the phyla Bacteroidetes, Acidobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria and Planctomycetes is also remarkable in most cases, and archaea represent a negligible fraction of the bioreactor communities (Jia et al. 2016; Ma et al. 2015a, b; Meng et al. 2016; Xu et al. 2016; Zhu et al. 2015, 2017; Ziembińska-Buczyńska et al. 2019).

Microorganisms have important function not only in the removal of particular contaminants, but also in the formation of biological structures (i.e., activated sludge flocs and biofilms) that are essential for the optimal operation of the bioreactors. Although it has to be mentioned that there is a significant fraction of bacteria that cannot be identified at the genus level, their function in coke plant effluent wastewater treatment remains unknown (Ma et al. 2015a, b; Zhu et al. 2015).

Phenol-degrading bacteria

Phenol can be utilized as carbon and energy source by many bacteria (Krastanov et al. 2013), and under suitable conditions complete oxidation could take place even at very high (up to 1–3 g/L) concentration (Arutchelvan et al. 2005; El-Sayed et al. 2003; Essam et al. 2010; Felföldi et al. 2010; Geng et al. 2006).

The first step in aerobic biodegradation is the hydroxylation of phenol to catechol using molecular oxygen (Caspi et al. 2018). Subsequently, catechol could be degraded via two major pathways: the ortho-pathway starts with the intradiol ring cleavage between the two hydroxyl groups (using the key enzyme catechol 1,2-dioxygenase) and meta-pathway with extradiol ring cleavage between one hydroxylated and its adjacent non-hydroxylated carbon (using the key enzyme catechol 2,3-dioxygenase) (Harayama and Rekik 1989; van Schie and Young 2000). The following steps of both routes result in central metabolic intermediates, such as pyruvate, acetaldehyde or succinate, that could enter into various pathways (e.g., the tricarboxylic acid cycle) (Caspi et al. 2018). The aerobic degradation of other aromatic compounds is also channeled to catechol or similar molecules (that contain two hydroxyl groups or a hydroxyl and a carboxyl group next to each other), which are subsequently subjected to ring cleavage (Fuchs 2008).

There is a wide diversity of phenol-degrading microorganisms in natural environments (Baek et al. 2003; Filipowicz et al. 2017; Krastanov et al. 2013; van Schie and Young 2000; Vedler et al. 2013) and also in coke plant effluent processing biological units (Table 3). In the latter case, most important bacterial species belong to the genera Alcaligenes, Castellaniella, Comamonas, Pseudomonas and Thauera (Felföldi et al. 2010; Ma et al. 2015a; Manefield et al. 2002; Zhang et al. 2004). Several studies have demonstrated that even a single aerobic reactor may contain many phenol-degrading species and genotypes with different phenol degradation kinetics (Felföldi et al. 2010; Mao et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2004). Such diversity of coexisting bacteria could be attributed to the fact that the concentration of phenolics often fluctuates in reactors and the composition of aromatic compounds is usually very complex resulting in a number of different ecological niches (Li et al. 2003; Zhang et al. 2004). Furthermore, genes involved in the biodegradation pathways could be acquired by horizontal gene transfer (Harayama and Rekik 1989; Peters et al. 2004); therefore, loss or gain of plasmids might alter the spectrum of phenol degraders even within the same reactor. On the other hand, selective and relatively constant conditions that are present in wastewater-treating bioreactors possibly do not favor maintaining genes responsible for biodegradation on mobile genetic elements (Bramucci and Nagarajan 2006).

Anaerobic degradation of aromatic compounds was also reported, but with a different strategy as used in aerobic metabolism. The central intermediate of these pathways is benzoyl-coenzyme A, and during the subsequent transformations, the ring is opened hydrolytically (Fuchs 2008; Harwood et al. 1999; Zhao and Liu 2016; Zhu et al. 2018). Such biodegradation potential was described in the denitrifying bacterium Thauera (Anders et al. 1995; Mechichi et al. 2002), which was also detected in anaerobic coke effluent treatment reactors (Ma et al. 2015a), and the phenomenon of phenol biodegradation under anaerobic and/or denitrifying conditions was reported several times in laboratory-scale systems (Beristain-Cardoso et al. 2009; Li et al. 2003; Vázquez et al. 2006).

Although the removal of phenolics is usually carried out by bacteria, some fungi (Aspergillus sp., Fusarium sp., Penicillium sp., Graphium sp.) were also isolated from stainless steel industry wastewaters that are capable of phenol degradation (Santos and Linardi 2004) or were reported to be able to degrade phenolic compounds present in coking wastewater (Lu et al. 2009).

Removal of other organic compounds (e.g., PAHs) could be also achieved through biological processes, but adsorption to activated sludge particles may also contribute significantly to their elimination in the biological treatment units (Zhang et al. 2012; Zhao et al. 2018).

Thiocyanate-degrading bacteria

Thiocyanate can be utilized as energy, carbon, nitrogen or sulfur source for microorganisms (Sorokin et al. 2001). There are two bacterial biodegradation pathways of this compound that result in the same end products but differ in the main intermediate metabolite (Caspi et al. 2018; Ebbs 2004; Hung and Pavlostathis 1997; Katayama et al. 1992; Stratford et al. 1994; Youatt 1954); the cyanate pathway (using the key enzyme cyanase):

and the carbonyl sulfide pathway (using the key enzyme thiocyanate hydrolase):

Such aerobic biodegradation routes of thiocyanate could lower the pH of the environment through the oxidation of the produced hydrogen sulfide to sulfuric acid (Sorokin et al. 2001; Staib and Lant 2007):

Several autotrophic and heterotrophic bacterial species belonging to various genera were reported to be capable of thiocyanate removal in pure or mixed cultures, some of them even under anaerobic and alkalophilic conditions: Klebsiella (Lee et al. 2003), Methylobacterium (Wood et al. 1998), Paracoccus (Katayama et al. 1995), Pseudomonas (Karavaiko et al. 2000; Mekuto et al. 2016), Thiohalobacter (Oshiki et al. 2019; Sorokin et al. 2010), Thiohalophilus (Sorokin et al. 2007) and Thioalkalivibrio (Sorokin et al. 2001, 2002, 2004). However, thiocyanate degradation in coke effluent-treating systems was almost exclusively assigned to Thiobacillus (e.g., T. thioparus, formerly known as T. thiocyanoxidans) (Ma et al. 2015a; Raper et al. 2019b; Xu et al. 2016). Nevertheless, cultivation-independent studies have revealed that yet unknown bacteria may also be involved in the process (Shoji et al. 2014). Interestingly, there is a fungal species, Acremonium strictum (formerly Cephalosporium acremonium), that was isolated from coking wastewater and is also capable of thiocyanate biodegradation (Kwon et al. 2002).

Some compounds present at high concentration in the coke plant effluent could be inhibitory for thiocyanate biodegradation, e.g., ammonium (if its concentration is higher than 300 mg/L) or phenols (if higher than 180 mg/L) (Raper et al. 2019b).

Bacteria responsible for nitrogen removal: nitrifying and denitrifying bacteria

Nitrogen (ammonia) removal in the biological unit could be achieved with a combination of the aerobic nitrification (ammonia to nitrate) and anaerobic denitrification (nitrate to nitrogen gas) processes in two separate bioreactors (see “Appendix”). If the anaerobic reactor is the first in the reactor cascade, denitrification takes place in the beginning, and to supply electron acceptors for the process nitrate is often channeled back from a subsequent aerobic bioreactor (Maranón et al. 2008). Ammonia is present in the chemically treated coke plant effluent itself; however, it is generated biologically during the degradation of NHCs and thiocyanate (see Eqs. 2–3; Table 1).

In the case of aerobic autotrophic nitrification, ammonia is oxidized to nitrate via nitrite by two phylogenetically distinct chemolithotrophic bacterial groups (ammonia- and nitrite-oxidizing bacteria), which is coupled with CO2-fixation and requires oxygen as electron acceptor (Bock and Wagner 2013). Ammonia is oxidized to hydroxylamine first and further to nitrite by two enzymes ammonia monooxygenase and hydroxylamine oxidoreductase, respectively. The generated nitrite is oxidized to nitrate by the nitrite oxidoreductase enzyme of the nitrite-oxidizing bacteria. Some Nitrospira are able to perform complete ammonia oxidation (comammox) to nitrate (Daims et al. 2015), although such comammox bacteria have not been detected yet in bioreactors fed with coking wastewater.

Optimal operation parameters for both nitrifying groups (temperature, 20–35 °C; dissolved oxygen concentration, 3–6 mg/L; and pH, 6.5–8.5; Geets et al. 2006; Kim et al. 2007; Raper et al. 2018a) are necessary for satisfactory bioreactor performance (see also “Appendix”). The nitrification process could be inhibited by several compounds present in the coke effluent (Zhao and Liu 2016), such as phenol and thiocyanate at concentration higher than 100–200 mg/L (Kim et al. 2008b), and cyanide higher than 0.1–0.2 mg/L (Kim et al. 2007, 2008b; Ryu et al. 2009). Furthermore, nitrite-oxidizing bacteria are more sensitive to low and fluctuating dissolved oxygen concentration than ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (Philips et al. 2002). Under low dissolved oxygen concentration or even anoxic conditions, ammonia-oxidizing bacteria are capable of denitrification using alternative electron acceptors (nitrite) (Bock and Wagner 2013). Additionally, cyanate (CNO−), which could be formed during the oxidation of thiocyanate (Eq. 1), may be used as energy source and converted to nitrate by some nitrifiers (Palatinszky et al. 2015), but this process has not been confirmed in the case of coke plant effluent-treating bioreactors.

In coking wastewater-treating bioreactors, ammonia oxidizers Nitrosomonas and Nitrosospira and nitrite oxidizers Nitrospira and Nitrobacter were detected previously (Ma et al. 2015a; Meng et al. 2016; Zhu et al. 2015). However, it has been recently presumed that heterotrophic nitrification in coke plant effluent-treating bioreactors could be in many cases more important than autotrophic, and genera like Acinetobacter, Comamonas, Pseudomonas and Thauera may be the key microorganisms in this process and possibly outcompete autotrophs due to the high amount of organic compounds present in the treated wastewater (Liu et al. 2015; Ma et al. 2015a, b; Yang et al. 2017; Ziembińska-Buczyńska et al. 2019).

During the denitrification process, heterotrophic microorganisms typically under anaerobic conditions reduce nitrate first to nitrite, then to different nitrogen–oxides and finally to nitrogen gas (Ruiz et al. 2005). Among various enzymes involved in the denitrification process, nitrate reductase is partly, whereas nitrite reductase is completely inhibited by dissolved oxygen concentration higher than 5.6 mg/L, and high nitrate concentration is also inhibitory to the nitrite reductase enzyme (Philips et al. 2002). There are several genera which could perform denitrification in bioreactors operating with coking wastewater, probably the most important are Azoarcus, Comamonas and Thauera (Table 3).

Some genera may have dual role in the bioreactors and conduct not only denitrification but organic compound or thiocyanate removal in parallel. Some members of, e.g., Comamonas and Thauera are able to perform denitrification (Brenner et al. 2005; Gumaelius et al. 2001), but these genera were reported as effective phenol degraders even in coke effluent-treating bioreactors (Felföldi et al. 2010; Mao et al. 2010; Qiao et al. 2018). Thiobacillus dentirificans is capable for denitrification with reduced inorganic sulfur species (Brenner et al. 2005) (e.g., with the H2S which is generated during the biodegradation of thiocyanate; Eqs. 1 and 4), and it was reported that Thiobacillus may represent a major component of the total bacterial community in bioreactors operating with coking wastewater (Ma et al. 2015a; Raper et al. 2019b). Removal of some NHCs could be achieved under anoxic conditions by denitrifiers that use NHCs both as carbon source and electron donor and simultaneously remove nitrate by utilizing it as electron acceptor and consequently transforming it to nitrogen gas (Li et al. 2001).

Floc-forming bacteria

Although there are fixed-film systems available and the presence of extracellular polymeric substances in biofilms may prevent bacteria from the harmful effect of contaminants (Ziembińska-Buczyńska et al. 2019), biological treatment of coking wastewater is mainly carried out using activated sludge-based technologies (Zhu et al. 2017).

Activated sludge systems perform two main processes, the biotransformation of soluble substrates (or particulate material that is solubilized by microorganisms) and the flocculation of newly formed biomass (Horan 2003; Bitton 2011). Sludge flocs may vary in shape and size from a few μm up to some mm, but usually have an average diameter around 50–180 µm (Schmid et al. 2003; Han et al. 2012) (Fig. 1). Besides bacterial cells, flocs contain organic and inorganic particles (as well as eukaryotic microorganisms if the concentration of toxic compounds is relatively low) (Horan 2003). It should be noted that significant heterogeneity is present in these small structures (e.g., in aerated reactors the inner part of flocs may be anoxic or even anaerobic) and such diverse microhabitats allow high bacterial diversity (Han et al. 2012; Wu et al. 1987). Filamentous bacteria may also be present in activated sludge bioreactors. However, increasing number of filaments results in poor sludge settling characteristics (Schmid et al. 2003).

Micrographs of various floc structures. a–c. Activated sludge flocs from different reactors of a laboratory-scale system treating coke plant effluent (see “Appendix”; a: aerobic reactor for the removal of phenols and thiocyanate, b: aerobic nitrification reactor, c: anoxic denitrification reactor); d. Flocs of Ottowia pentelensis PB3-7BT in liquid culture. Scale bar: 25 μm

Some floc-forming strains of the genus Ottowia were isolated from bioreactors treating coke plant effluents (Felföldi et al. 2011; Geng et al. 2014) (Fig. 1) and were suggested to be important structural and functional members of the bacterial communities of the reactors.

Conclusions for future biology

Microorganisms perform similar activity in artificial environments (e.g., in bioreactors) as in natural environments, and biological removal of contaminants in many cases provides a cost-effective and environmental-friendly alternative compared to chemical treatment or incineration (Bramucci and Nagarajan 2006; Chen et al. 2017; Zhao and Liu 2016). Parameters monitored during the operation of bioreactors usually refer to composite function (e.g., biological oxygen demand) or macroscopic characteristic (e.g., settling) (Bramucci and Nagarajan 2006). However, the processes that are responsible for the observed phenomena and measured values are conducted by microorganisms. This review aimed to open the ``black box'' of microbial activity and provided a theoretical (i.e., microbiological) basis for technical issues, since a better understanding the background of biological processes (at molecular, cellular or community level), which are responsible for the removal of a particular contaminant, helps the optimization of treatment technologies and aids the design of new management techniques. Nevertheless, problematic processes still exist during the biological treatment of coke plant effluents, like fine-tuning of nitrogen removal or the elimination of recalcitrant organic compounds (Raper et al. 2018a; Zhu et al. 2018). Recently, the effective combination of biological systems with physicochemical purification processes is a promising trend to enhance the removal efficiency of refractory pollutants (Zhu et al. 2018). Such improvements are indispensable for the continuously increasing demand for available clean water. Furthermore, developing newer water-saving technologies in iron and steel industry, the utilization of alternative water sources (i.e., replacing a portion of freshwater with rain water, mine water and reclaimed water from urban wastewater treatment plants), recycling and reusing of treated coking wastewater could also contribute to environmental protection (Tong et al. 2018).

On the other hand, the harsh environment of coke plant effluent-treating bioreactors harbors (Ma et al. 2015a; Shoji et al. 2014) and therefore represents a source of previously uncultivated bacteria. In the last years, several novel species and genera have been described from such bioreactors (Cao et al. 2014; Felföldi et al. 2011, 2014a, b; Geng et al. 2014, 2015; Ren et al. 2015). Isolated strains and cocultures contribute to understand the ecology and phenotypic features of bacteria, therefore describing global biodiversity, but they can be also applied for bioaugmentation to enhance the performance of the biological treatment unit and community assembly during reactor setup or after a reactor failure (Raper et al. 2018b; Zhu et al. 2015, 2018).

References

Anders HJ, Kaetzke A, Kämpfer P, Ludwig W, Fuchs G (1995) Taxonomic position of aromatic-degrading denitrifying pseudomonad strains K 172 and KB 740 and their description as new members of the genera Thauera, as Thauera aromatica sp. nov., and Azoarcus, as Azoarcus evansii sp. nov., respectively, members of the beta subclass of the Proteobacteria. Int J Syst Bacteriol 45:327–333

Arutchelvan V, Kanakasabai V, Nagarajan S, Muralikrishnan V (2005) Isolation and identification of novel high strength phenol degrading bacterial strains from phenol-formaldehyde resin manufacturing industrial wastewater. J Hazard Mater 127:238–243

Baek SH, Kim KH, Yin CR, Jeon CO, Im WT, Kim KK, Lee ST (2003) Isolation and characterization of bacteria capable of degrading phenol and reducing nitrate under low-oxygen conditions. Curr Microbiol 47:462–466

Banerjee G (1996) Phenol- and thiocyanate-based wastewater treatment in RBC reactor. J Environ Eng 122:941–948

Beristain-Cardoso R, Texier A-C, Alpuche-Solís Á, Gómez J, Razo-Flores E (2009) Phenol and sulfide oxidation in a denitrifying biofilm reactor and its microbial community analysis. Proc Biochem 44:23–28

Bitton G (2011) Wastewater microbiology. Wiley, Hoboken

Bock E, Wagner M (2013) Oxidation of inorganic nitrogen compounds as an energy source. In: Rosenberg E, DeLong EF, Lory S, Stackebrandt E, Thompson F (eds) The prokaryotes—prokaryotic physiology and biochemistry, 4th edn. Springer, Berlin, pp 83–118

Bramucci M, Nagarajan V (2006) Bacterial communities in industrial wastewater bioreactors. Curr Opin Microbiol 9:275–278

Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (eds) (2005) Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. The proteobacteria, vol 2, 2nd edn. Springer, New York

Cao J, Lai Q, Liu Y, Li G, Shao Z (2014) Ottowia beijingensis sp. nov., isolated from coking wastewater activated sludge, and emended description of the genus Ottowia. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 64:963–967

Caspi R, Billington R, Fulcher CA, Keseler IM, Kothari A, Krummenacker M, Latendresse M, Midford PE, Ong Q, Ong WK, Paley S, Subhraveti P, Karp PD (2018) The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes. Nucleic Acids Res 46:D633–D639

Chen Y, Lan S, Wang L, Dong S, Zhou H, Tan Z, Li X (2017) A review: driving factors and regulation strategies of microbial community structure and dynamics in wastewater treatment systems. Chemosphere 174:173–182

Chen L, Xu Y, Sun Y (2019) Combination of coagulation and ozone catalytic oxidation for pretreating coking wastewater. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16:E1705

Cydzik-Kwiatkowska A, Zielińska M (2016) Bacterial communities in full-scale wastewater treatment systems. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 32:66

Daims H, Lebedeva EV, Pjevac P, Han P, Herbold C, Albertsen M, Jehmlich N, Palatinszky M, Vierheilig J, Bulaev A, Kirkegaard RH, von Bergen M, Rattei T, Bendinger B, Nielsen PH, Wagner M (2015) Complete nitrification by Nitrospira bacteria. Nature 528:504–509

Davis ML (2010) Water and wastewater engineering—design principles and practice. McGraw-Hill, New York

Ebbs S (2004) Biological degradation of cyanide compounds. Curr Opin Biotechnol 15:231–236

El-Sayed WS, Ibrahim MK, Abu-Shady M, El-Beih F, Ohmura N, Saiki H, Ando A (2003) Isolation and characterization of phenol-catabolizing bacteria from a coking plant. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 67:2026–2029

Essam T, Amin MA, El Tayeb O, Mattiasson B, Guieysse B (2010) Kinetics and metabolic versatility of highly tolerant phenol degrading Alcaligenes strain TW1. J Hazard Mater 173:783–788

Felföldi T, Székely AJ, Gorál R, Barkács K, Scheirich G, András J, Rácz A, Márialigeti K (2010) Polyphasic bacterial community analysis of an aerobic activated sludge removing phenols and thiocyanate from coke plant effluent. Bioresour Technol 101:3406–3414

Felföldi T, Kéki Zs, Sipos R, Márialigeti K, Tindall BJ, Schumann P, Tóth EM (2011) Ottowia pentelensis sp. nov., a floc-forming betaproteobacterium isolated from an activated sludge system treating coke plant effluent. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 61:2146–2150

Felföldi T, Vengring A, Kéki Zs, Márialigeti K, Schumann P, Tóth EM (2014a) Eoetvoesia caeni gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from an activated sludge system treating coke plant effluent. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 64:1920–1925

Felföldi T, Vengring A, Márialigeti K, András J, Schumann P, Tóth EM (2014b) Hephaestia caeni gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel member of the family Sphingomonadaceae isolated from activated sludge. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 64:738–744

Felföldi T, Jurecska L, Vajna B, Barkács K, Makk J, Cebe G, Szabó A, Záray Gy, Márialigeti K (2015) Texture and type of polymer fiber carrier determine bacterial colonization and biofilm properties in wastewater treatment. Chem Eng J 264:824–834

Filipowicz N, Momotko M, Boczkaj G, Pawlikowski T, Wanarska M, Cieśliński H (2017) Isolation and characterization of phenol-degrading psychrotolerant yeasts. Water Air Soil Pollut 228:210

Fuchs G (2008) Anaerobic metabolism of aromatic compounds. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1125:82–99

Geets J, Boon N, Verstraete W (2006) Strategies of aerobic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria for coping with nutrient and oxygen fluctuations. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 58:1–13

Geng A, Soh AE, Lim CJ, Loke LC (2006) Isolation and characterization of a phenol-degrading bacterium from an industrial activated sludge. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 71:728–735

Geng S, Pan X, Mei R, Wang Y, Sun JQ, Liu XY, Tang YQ, Wu XL (2014) Ottowia shaoguanensis sp. nov., isolated from coking wastewater. Curr Microbiol 68:324–329

Geng S, Pan XC, Mei R, Wang YN, Sun JQ, Liu XY, Tang YQ, Wu XL (2015) Paradevosia shaoguanensis gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from a coking wastewater. Curr Microbiol 70:110–118

Ghose MK (2002) Complete physico-chemical treatment for coke plant effluents. Wat Res 36:1127–1134

Gumaelius L, Magnusson G, Pettersson B, Dalhammar G (2001) Comamonas denitrificans sp. nov., an efficient denitrifying bacterium isolated from activated sludge. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 51:999–1006

Han Y, Liu J, Guo X, Li L (2012) Micro-environment characteristics and microbial communities in activated sludge flocs of different particle size. Bioresour Technol 124:252–258

Harayama S, Rekik M (1989) Bacterial aromatic ring-cleavage enzymes are classified into two different gene families. J Biol Chem 264:15328–15333

Harwood CS, Burchhardt G, Herrmann H, Fuchs G (1999) Anaerobic metabolism of aromatic compounds via the benzoyl-CoA pathway. FEMS Microbiol Rev 22:439–458

Hasanbeigi A, Arens M, Price L (2014) Alternative emerging ironmaking technologies for energy-efficiency and carbon dioxide emissions reduction: a technical review. Renew Sust Energ Rev 33:645–658

Horan N (2003) Suspended growth processes. In: Mara D, Horan N (eds) The handbook of water and wastewater microbiology. Academic Press, London, pp 351–360

Hung C-H, Pavlostathis SG (1997) Aerobic biodegradation of thiocyanate. Water Res 31:2761–2770

Ji Q, Tabassum S, Hena S, Silva CG, Yu G, Zhang Z (2016) A review on the coal gasification wastewater treatment technologies: past, present and future outlook. J Clean Prod 126:38–55

Jia S, Han H, Zhuang H, Hou B (2016) The pollutants removal and bacterial community dynamics relationship within a full-scale British Gas/Lurgi coal gasification wastewater treatment using a novel system. Bioresour Technol 200:103–110

Jurecska L, Barkács K, Kiss É, Gyulai G, Felföldi T, Törő B, Kovács R, Záray Gy (2013) Intensification of wastewater treatment with polymer fiber-based biofilm carriers. Microchem J 107:108–114

Karavaiko GI, Kondrat’eva TF, Savari EE, Grigor’eva NV, Avakyan ZA (2000) Microbial degradation of cyanide and thiocyanate. Microbiology 69:209–216 (Engl. Trans. Mikrobiologiya)

Katayama Y, Narahara Y, Inoue Y, Amano F, Kanagawa T, Kuraishi H (1992) A thiocyanate hydrolase of Thiobacillus thioparus—a novel enzyme catalyzing the formation of carbonyl sulfide from thiocyanate. J Biol Chem 267:9170–9175

Katayama Y, Hiraishi A, Kuraishi H (1995) Paracoccus thiocyanatus sp. nov., a new species of thiocyanate-utilizing facultative chemolithotroph, and transfer of Thiobacillus versutus to the genus Paracoccus as Paracoccus versutus comb. nov. with emendation of the genus. Microbiology 141:1469–1477

Kim YM, Park D, Lee DS, Park JM (2007) Instability of biological nitrogen removal in a cokes wastewater treatment facility during summer. J Hazard Mater 141:27–32

Kim YM, Park D, Jeon CO, Lee DS, Park JM (2008a) Effect of HRT on the biological pre-denitrification process for the simultaneous removal of toxic pollutants from cokes wastewater. Bioresour Technol 99:8824–8832

Kim YM, Park D, Lee DS, Park JM (2008b) Inhibitory effects of toxic compounds on nitrification process for cokes wastewater treatment. J Hazard Mater 152:915–921

Kim YM, Park D, Lee DS, Jung KA, Park JM (2009) Sudden failure of biological nitrogen and carbon removal in the full-scale pre-denitrification process treating cokes wastewater. Bioresour Technol 100:4340–4347

Kjeldsen P (1999) Behaviour of cyanide in soil and groundwater: a review. Water Air Soil Pollut 115:279–307

Kozak J, Wlodarczyk-Makula M (2018) Comparison of the PAHs degradation effectiveness using CaO2 or H2O2 under the photo-Fenton reaction. Desalin Water Treat 134:57–64

Krastanov A, Alexieva Z, Yemendzhiev H (2013) Microbial degradation of phenol and phenolic derivatives. Eng Life Sci 13:76–87

Kwiecińska A, Lajnert R, Bigda AR (2017) Coke oven wastewater—formation, treatment and utilization methods—a review. Proc ECOpole 11:19–28

Kwon HK, Woo SH, Park JM (2002) Thiocyanate degradation by Acremonium strictum and inhibition by secondary toxicants. Biotechnol Lett 24:1347–1351

Lee C, Kim J, Chang J, Hwang S (2003) Isolation and identification of thiocyanate utilizing chemolithotrophs from gold mine soils. Biodegradation 14:183–188

Li Y, Gu G, Zhao J, Yu H (2001) Anoxic degradation of nitrogenous heterocyclic compounds by acclimated activated sludge. Process Biochem 37:81–86

Li YM, Gu GW, Zhao JF, Yu HQ, Qiu YL, Peng YZ (2003) Treatment of coke-plant wastewater by biofilm systems for removal of organic compounds and nitrogen. Chemosphere 52:997–1005

Liu Y, Hu T, Song Y, Chen H, Lv Y (2015) Heterotrophic nitrogen removal by Acinetobacter sp. Y1 isolated from coke plant wastewater. J Biosci Bioeng 120:549–554

Lu Y, Yan L, Wang Y, Zhou S, Fu J, Zhang J (2009) Biodegradation of phenolic compounds from coking wastewater by immobilized white rot fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium. J Hazard Mater 165:1091–1097

Ma Q, Qu Y, Shen W, Zhang Z, Wang J, Liu Z, Li D, Li H, Zhou J (2015a) Bacterial community compositions of coking wastewater treatment plants in steel industry revealed by Illumina high-throughput sequencing. Bioresour Technol 179:436–443

Ma Q, Qu YY, Zhang XW, Shen WL, Liu ZY, Wang JW, Zhang ZJ, Zhou JT (2015b) Identification of the microbial community composition and structure of coal-mine wastewater treatment plants. Microbiol Res 175:1–5

Maiti D, Ansari I, Rather MA, Deepa A (2019) Comprehensive review on wastewater discharged from the coal-related industries—characteristics and treatment strategies. Water Sci Technol 79:2023–2035

Manefield M, Whiteley AS, Griffiths RI, Bailey MJ (2002) RNA stable isotope probing, a novel means of linking microbial community function to phylogeny. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:5367–5373

Mao Y, Zhang X, Xia X, Zhong H, Zhao L (2010) Versatile aromatic compound degrading capacity and microdiversity of Thauera strains isolated from a coking wastewater treatment bioreactor. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 37:927–934

Maranón E, Vázquez I, Rodríguez J, Castrillón L, Fernández Y (2008) Coke wastewater treatment by a three-step activated sludge system. Water Air Soil Pollut 192:155–164

Mechichi T, Stackebrandt E, Gad’on N, Fuchs G (2002) Phylogenetic and metabolic diversity of bacteria degrading aromatic compounds under denitrifying conditions, and description of Thauera phenylacetica sp. nov., Thauera aminoaromatica sp. nov., and Azoarcus buckelii sp. nov. Arch Microbiol 178:26–35

Mekuto L, Ntwampe SKO, Kena M, Golela MT, Amodu OS (2016) Free cyanide and thiocyanate biodegradation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa STK 03 capable of heterotrophic nitrification under alkaline conditions. 3 Biotech 6:6

Meng XJ, Li HB, Cao HB, Sheng YX (2016) Bacterial community composition of activated sludge from coking wastewater. Huan Jing Ke Xue 37:3923–3930 (Article in Chinese)

Neufeld RD, Valiknac T (1979) Inhibition of phenol degradation by thiocyanate. J Water Pollut Control Fed 51:2283–2291

Nowak MA, Paul AD, Srivastava RD, Radziwon A (2004) Coal conversion. In: Cleveland CJ (ed) Encyclopedia of energy. Elsevier, New York, pp 425–434

Olson GJ, Brierley JA, Brierley CL (2003) Bioleaching review part B: progress in bioleaching: applications of microbial processes by the minerals industries. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 63:249–257

Oshiki M, Fukushima T, Kawano S, Kasahara Y, Nakagawa J (2019) Thiocyanate degradation by a highly enriched culture of the neutrophilic halophile Thiohalobacter sp. strain FOKN1 from activated sludge and genomic insights into thiocyanate metabolism. Microbes Environ 34:402–412

Padoley KV, Mudliar SN, Pandey RA (2008) Heterocyclic nitrogenous pollutants in the environment and their treatment options—an overview. Bioresour Technol 99:4029–4043

Palatinszky M, Herbold C, Jehmlich N, Pogoda M, Han P, von Bergen M, Lagkouvardos I, Karst SM, Galushko A, Koch H, Berry D, Daims H, Wagner M (2015) Cyanate as an energy source for nitrifiers. Nature 524:105–108

Peters M, Tomikas A, Nurk A (2004) Organization of the horizontally transferred pheBA operon and its adjacent genes in the genomes of eight indigenous Pseudomonas strains. Plasmid 52:230–236

Philips S, Laanbroek HJ, Verstraete W (2002) Origin, causes and effects of increased nitrite concentration in aquatic environments. Rev Env Sci Biotechnol 1:115–141

Qiao N, Xi L, Zhang J, Liu D, Ge B, Liu J (2018) Thauera sinica sp. nov., a phenol derivative-degrading bacterium isolated from activated sludge. Antonie van Leeuw J Microb 111:945–954

Raper E, Fisher R, Anderson DR, Stephenson T, Soares A (2018a) Alkalinity and external carbon requirements for denitrification–nitrification of coke wastewater. Environ Technol 39:2266–2277

Raper E, Stephenson T, Simões F, Fisher R, Anderson DR, Soares A (2018b) Enhancing the removal of pollutants from coke wastewater by bioaugmentation: a scoping study. J Chem Technol Biotechnol 93:2535–2543

Raper E, Fisher R, Anderson DR, Stephenson T, Soares A (2019a) Nitrogen removal from coke making wastewater through a pre-denitrification activated sludge process. Sci Total Environ 666:31–38

Raper E, Stephenson T, Fisher R, Anderson DR, Soares A (2019b) Characterisation of thiocyanate degradation in a mixed culture activated sludge process treating coke wastewater. Bioresour Technol 288:121524

Remus R, Aguado-Monsonet MA, Roudier S, Sancho LD (2013) Best available techniques (BAT) reference document for iron and steel production. Industrial Emissions Directive 2010/75/EU, European Commission. https://doi.org/10.2791/97469

Ren Y, Chen SY, Yao HY, Deng LJ (2015) Lysinibacillus cresolivorans sp. nov., an m-cresol-degrading bacterium isolated from coking wastewater treatment aerobic sludge. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 65:4250–4255

Rowan AK, Snape JR, Fearnside D, Barer MR, Curtis TP, Head IM (2003) Composition and diversity of ammonia-oxidising bacterial communities in wastewater treatment reactors of different design treating identical wastewater. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 43:195–206

Ruiz G, Jeison D, Rubilar O, Ciudad G, Chamy R (2005) Nitrification-denitrification via nitrite accumulation for nitrogen removal from wastewaters. Bioresour Technol 97:330–335

Ryu H-D, Cho Y-O, Lee S-I (2009) Effect of ferrous ion coagulation on biological ammonium nitrogen removal in treating coke wastewater. Environ Eng Sci 26:1739–1746

Santos VL, Linardi VR (2004) Biodegradation of phenol by a filamentous fungi isolated from industrial effluents—identification and degradation potential. Proc Biochem 39:1001–1006

Schmid M, Thill A, Purkhold U, Walcher M, Bottero JY, Ginestet P, Nielsen PH, Wuertz S, Wagner M (2003) Characterization of activated sludge flocs by confocal laser scanning microscopy and image analysis. Water Res 37:2043–2052

Shifrin NS, Beck BD, Gauthier TD, Chapnick SD, Goodman G (1996) Chemistry, toxicology, and human health risk of cyanide compounds in soils at former manufactured gas plant sites. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 23:106–116

Shoji T, Sueoka K, Satoh H, Mino T (2014) Identification of the microbial community responsible for thiocyanate and thiosulfate degradation in an activated sludge process. Process Biochem 49:1176–1181

Sorokin DY, Tourova TP, Lysenko AM, Kuenen JG (2001) Microbial thiocyanate utilization under highly alkaline conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol 67:528–538

Sorokin DY, Tourova TP, Lysenko AM, Mityushina LL, Kuenen JG (2002) Thioalkalivibrio thiocyanoxidans sp. nov. and Thioalkalivibrio paradoxus sp. nov., novel alkaliphilic, obligately autotrophic, sulfur-oxidizing bacteria capable of growth on thiocyanate, from soda lakes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 52:657–664

Sorokin DY, Tourova TP, Antipov AN, Muyzer G, Kuenen JG (2004) Anaerobic growth of the haloalkaliphilic denitrifying sulfur-oxidizing bacterium Thialkalivibrio thiocyanodenitrificans sp. nov. with thiocyanate. Microbiology 150:2435–2442

Sorokin DY, Tourova TP, Bezsoudnova EY, Pol A, Muyzer G (2007) Denitrification in a binary culture and thiocyanate metabolism in Thiohalophilus thiocyanoxidans gen. nov. sp. nov.—a moderately halophilic chemolithoautotrophic sulfur-oxidizing gammaproteobacterium from hypersaline lakes. Arch Microbiol 187:441–450

Sorokin DY, Kovaleva OL, Tourova TP, Muyzer G (2010) Thiohalobacter thiocyanaticus gen. nov., sp. nov., a moderately halophilic, sulfur-oxidizing gammaproteobacterium from hypersaline lakes, that utilizes thiocyanate. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 60:444–450

Staib C, Lant P (2007) Thiocyanate degradation during activated sludge treatment of coke-ovens wastewater. Biochem Eng J 34:122–130

Stamoudis VC, Luthy RG (1980) Determination of biological removal of organic constituents in quench waters from high-BTU coal-gasification pilot plants. Water Res 14:1143–1156

Stratford J, Dias AEXO, Knowles CJ (1994) The utilization of thiocyanate as a nitrogen source by a heterotrophic bacterium: the degradative pathway involves formation of ammonia and tetrathionate. Microbiology 140:2657–2662

Tong Y, Zhang Q, Cai J, Gao C, Wang L, Li P (2018) Water consumption and wastewater discharge in China’s steel industry. Ironmak Steelmak 45:868–877

van Schie PM, Young LY (2000) Biodegradation of phenol: mechanisms and applications. Bioremediation J 4:1–18

Vázquez I, Rodríguez J, Maranón E, Castrillón L, Fernández Y (2006) Simultaneous removal of phenol, ammonium and thiocyanate from coke wastewater by aerobic biodegradation. J Hazard Mater 137:1773–1780

Vedler E, Heinaru E, Jutkina J, Viggor S, Koressaar T, Remm M, Heinaru A (2013) Limnobacter spp. as newly detected phenol-degraders among Baltic Sea surface water bacteria characterised by comparative analysis of catabolic genes. Syst Appl Microbiol 36:525–532

Wood AP, Kelly DP, McDonald IR, Jordan SL, Morgan TD, Khan S, Murrell JC, Borodina E (1998) A novel pink-pigmented facultative methylotroph, Methylobacterium thiocyanatum sp. nov., capable of growth on thiocyanate as sole nitrogen source. Arch Microbiol 169:148–158

World Coal Association (2020) http://www.worldcoal.org. Accessed 20 Jan 2020

World Steel Association (2020) https://www.worldsteel.org. Accessed 30 May 2020

Wu W, Hu J, Gu X, Zhao Y, Zhang H, Gu G (1987) Cultivation of anaerobic granular sludge in UASB reactors with aerobic activated sludge as seed. Wat Res 21:789–799

Wu L, Ning D, Zhang B, Li Y, Zhang P, Shan X, Zhang Q, Brown MR, Li Z, Van Nostrand JD, Ling F, Xiao N, Zhang Y, Vierheilig J, Wells GF, Yang Y, Deng Y, Tu Q, Wang A, Global Water Microbiome Consortium, Zhang T, He Z, Keller J, Nielsen PH, Alvarez PJJ, Criddle CS, Wagner M, Tiedje JM, He Q, Curtis TP, Stahl DA, Alvarez-Cohen L, Rittmann BE, Wen X, Zhou J (2019) Global diversity and biogeography of bacterial communities in wastewater treatment plants. Nat Microbiol 4:1183–1195

Xu WC, Meng XJ, Yin L, Zhang YX, Li HB, Cao HB (2016) Biodiversity of thiocyanate-degrading bacteria in activated sludge from coking wastewater. Huan Jing Ke Xue 37:2689–2695 (Article in Chinese)

Yang Y, Liu Y, Yang T, Lv Y (2017) Characterization of a microbial consortium capable of heterotrophic nitrifying under wide C/N range and its potential application in phenolic and coking wastewater. Biochem Eng J 120:33–40

Youatt JB (1954) Studies on the metabolism of Thiobacillus thiocyanoxidans. J Gen Microbiol 11:139–149

Zhang M, Tay JH, Qian Y, Gu XS (1998) Coke plant wastewater treatment by fixed biofilm system for COD and NH3–N removal. Water Res 32:519–527

Zhang X, Gao P, Chao Q, Wang L, Senior E, Zhao L (2004) Microdiversity of phenol hydroxylase genes among phenol-degrading isolates of Alcaligenes sp. from an activated sludge system. FEMS Microbiol Lett 237:369–375

Zhang W, Wei C, Chai X, He J, Cai Y, Ren M, Yan B, Peng P, Fu J (2012) The behaviors and fate of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in a coking wastewater treatment plant. Chemosphere 88:174–182

Zhang L, Hwang J, Leng T, Xue G, Wu G (2016) Discussion on coking wastewater treatment and control measures in iron and steel enterprises. Charact Miner Met Mater 2016:159–165

Zhao Q, Liu Y (2016) State of the art of biological processes for coal gasification wastewater treatment. Biotechnol Adv 34:1064–1072

Zhao W, Sui Q, Huang X (2018) Removal and fate of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in a hybrid anaerobic-anoxic-oxic process for highly toxic coke wastewater treatment. Sci Total Environ 635:716–724

Zhu X, Tian J, Chen L (2012) Phenol degradation by isolated bacterial strains: kinetics study and application in coking wastewater treatment. J Chem Technol Biotechnol 87:123–129

Zhu X, Liu R, Liu C, Chen L (2015) Bioaugmentation with isolated strains for the removal of toxic and refractory organics from coking wastewater in a membrane bioreactor. Biodegradation 26:465–474

Zhu S, Wu H, Zhou L, Wei C (2017) The resilience of microbial community involved in coking wastewater treatment system. Next Gener Seq Appl 4:1

Zhu H, Han Y, Xu C, Han H, Ma W (2018) Overview of the state of the art of processes and technical bottlenecks for coal gasification wastewater treatment. Sci Total Environ 637–638:1108–1126

Ziembińska-Buczyńska A, Ciesielski S, Żabczyński S, Cema G (2019) Bacterial community structure in rotating biological contactor treating coke wastewater in relation to medium composition. Environ Sci Pollut Res 26:19171–19179

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to Katalin Barkács and Róbert Gorál for providing unpublished data.

Funding

TF was supported by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (Grant No. BO/00837/20/8). Open access funding provided by Eötvös Loránd University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Appendix

Case study: An example of a laboratory-scale O/O/A system treating coke plant effluent (Tamás Felföldi, Katalin Barkács, Róbert Gorál and Károly Márialigeti, unpublished results). Abbreviations: COD—chemical oxygen demand, DMC—dry matter content, dO2—dissolved oxygen concentration, HRT—hydraulic retention time, IC—inorganic carbon, Recirc—recirculation ratio, SVI—sludge volume index, TOC—total organic carbon, TN—total nitrogen, Vol—working volume, n.m.—not measured, n.a.—not applicable. Symbol ``+'' means that the component increased.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Felföldi, T., Nagymáté, Z., Székely, A.J. et al. Biological treatment of coke plant effluents: from a microbiological perspective. BIOLOGIA FUTURA 71, 359–370 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42977-020-00028-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42977-020-00028-2