Abstract

Voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) has been considered the gold standard for detecting and evaluating vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) among children. However, ionizing radiation exposure is a concern for this diagnostic modality. Contrast-enhanced voiding urosonography (ceVUS) is an alternative technique for the detection of vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) using ultrasound and intravesical administration of an ultrasound (US) contrast agent. ceVUS is a radiation-free, effective, and safe method for identifying and grading VUR. We performed a study specifically for our hospital. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of contrast-enhanced voiding urosonography (ceVUS) in the detection of vesicoureteral reflux and its grading in children, compared to voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG). If we consider VCUG as the gold standard, the sensitivity of ceVUS in our study was 83%, specificity was 100% and accuracy was 94%. Our positive cases had Grade II to V reflux on ceVUS and Grade I to V reflux on VCUG. In our small sample of 18 patients, the detection of vesicoureteral reflux by ceVUS was comparable to that of VCUG. ceVUS can be used as a radiation-free alternative to VCUG for the detection of VUR in children. A benefit of ceVUS is the ability to do cyclical assessment without the fear of increasing radiation dose, as you would with VCUG.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Vesicoureteral reflux occurs in 1 to 2% of the pediatric population [1,2,3,4,5]. It is defined as the retrograde flow of urine from the bladder to the urinary tract [1, 2, 6]. Undiagnosed and recurrent vesicoureteral reflux can lead to pyelonephritis, renal scarring, or even kidney failure. The primary pathogenesis of vesicoureteral reflux in early childhood is unclear. However, a congenital anomaly at the vesicoureteral junction is considered to be the cause [7]. It was found that a significant decrease in alpha actin, myosin, and desmin contents, as well as a high rate of atrophy and muscular dysfunction with disorganized muscular fibers, led to reflux. A strong genetic component for the presence of reflux has been postulated [8].

Voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) and, in recent years, contrast-enhanced voiding urosonography (ceVUS) have played an important role in diagnosing VUR. The ceVUS offers high sensitivity and specificity comparable to that of VCUG without radiation exposure. ceVUS shows excellent diagnostic sensitivity of up to 100% in detecting VUR [9,10,11], similar to VCUG. Lumason (Bracco DiagnosticsInc., Monroe, NJ, USA), known as Sonovue outside the United States, is an ultrasound contrast agent made of microbubbles that contain sulfur heaxaflouride and are stabilized by phospholipids. In contrast-enhanced voiding urosonography, the US contrast medium is instilled into the urinary bladder through the urinary catheter. The European Association of Urology continues to regard the VCUG as the gold standard in the diagnosis of VUR [12, 13]. However, as per the EFSUMB guidelines, ceVUS is particularly recommended for follow-up evaluation after conservative or post-surgical treatment, in the screening of high-risk patients such as siblings or patients after kidney transplantation [14]. One of the advantages of contrast-enhanced voiding urosonography is the relatively low contrast reaction compared to VCUG and no radiation. The examination can be performed at the bedside in a relaxed manner in a supine position, compared to VCUG which needs the patient to be shifted to the fluoroscopy room.

While ceVUS has demonstrated high diagnostic accuracy in previous studies, its ability to effectively identify and grade moderate to severe cases of VUR (Grade II to V) has not been thoroughly investigated. These grades of VUR are clinically significant, as they often require more aggressive management than lower grades and have a higher risk of renal complications.

This study was conducted to provide a focused assessment of the diagnostic accuracy of ceVUS compared to VCUG, specifically in pediatric patients with Grade II to V VUR. The rationale for concentrating on these grades is twofold: firstly, to determine whether ceVUS can reliably detect the presence and assess the severity of clinically significant reflux, and secondly, to evaluate the potential of ceVUS to replace VCUG in routine clinical practice for these particular cases. By homing in on Grade II to V VUR, we aim to address a gap in the literature and contribute to safer and more accurate diagnostic practices in pediatric urology.

Materials and methods

The study was approved by Institutional Review Board. Over 16 months, 20 patients needing evaluation for vesicoureteral reflux were recruited. Two patients consented but were excluded from the study; one could not be catheterized, and the other was excluded due to inadvertent catheterization of a ureterocele and refusal for re-catheterization. Before being enrolled in the study details of the procedure and the potential risks were explained to the parents and to the patients who were older than 8 years of age. Informed consent was obtained from the parents and assent was obtained from the patients who were 8 years and older. All examinations were performed in the supine position. Ultrasound examinations were performed using GE (General Electric, Milwaukee) LOGIQ E9 XD CLEAR 2.0, software R6 and up-to-date CEUS protocols. To avoid early destruction of the injected microbubbles, a low mechanical index of < 0.2 (0.11–0.15) was used during the ultrasound exam.

Patients were catheterized in a sterile manner to safely administer the contrast medium before the study. The amount of contrast agent used ranged from 50 to 500 ml, depending on age of the patient and size of the urinary bladder (Table 1).

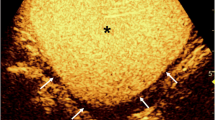

Contrast-enhanced voiding urosonography was first performed using 0.2% Lumason solution which is a second-generation contrast agent. Before contrast administration, baseline grey-scale images of the kidneys and urinary bladder were acquired. The depiction of echogenic microbubbles in the ureters or pelvicalyceal system confirms the presence of VUR [15]. This was followed by a standard fluoroscopic voiding cystourethrogram. The same catheter was used (without removal) for both studies until voiding during VCUG portion of the study. Both ceVUS and VCUG were performed and interpreted by the same pediatric radiologist (PKS) with 14 years of experience in ultrasound and 6 years in pediatric radiology. Cyclic filling of the urinary bladder was performed in neonates and infants who voided at low volumes (Table 2).

After ceVUS was performed, the patient data and the imaging files were stored in the in-house PACS (Picture archiving and communication system-CHANGE corporation) to allow further analysis and a follow-up detailed review of exam images (Fig. 1).

On VCUG and ceVUS, vesicoureteric reflux was graded into five grades following the international system of radiographic grading of vesicoureteric reflux [10, 16]:

VUR grade I—contrast medium reaching the ureter only.

VUR grade II—contrast medium reaching the ureter and renal pelvis without dilatation.

VUR grade III—contrast medium reaching mildly to moderately dilated ureter and mildly to moderately dilated renal pelvis with no to slightly blunted fornices.

VUR grade IV—contrast medium reaching moderately dilated and/or tortuous ureter and moderately dilated renal pelvis and calyces with complete obliteration of sharp angles of fornices but maintenance of papillary impressions in most calyces.

VUR grade V—contrast medium reaching grossly dilated and tortuous ureter and grossly dilated renal pelvis and calyces with papillary impressions not visible in most calyces.

Any immediate adverse events were noted. In addition, a 48-h follow-up phone interview with the patients’ caregiver was performed to inquire about the potential side effects.

Histogram was used to visualize and compare the distribution of grades estimated by ceVUS and VCUG. The estimated grades and reflux detection accuracy (whether detected or not) of ceVUS and VCUG were evaluated using Spearman correlation coefficient and Mann–Whitney U test to assess the degree of association and differences between them, respectively. Further, a confusion matrix was used to compute the sensitivity, specificity, precision, and accuracy of ceVUS grades compared with VCUG grades. SPSS (version 29; SPSS, IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the analysis. A two-tailed p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests (Fig. 2).

Results

A total of 39 pelviureteric units were studied in 18 patients. The group consisted of 9 males and 9 females. The age distribution ranged from 23 days to 17 years. Seven patients had urinary tract infections (UTI), other indications included hydronephrosis, multicystic dysplastic kidneys, renal agenesis, ureterocoele, posterior urethral valve, echogenic kidneys, and pelvic ectasia. Two patients had solitary kidneys and three had duplicated pelvicalyceal systems. Reflux was noted in six pelviureteric units. On ceVUS, one patient had a grade II reflux, one had grade III reflux, two had grade IV reflux and one had grade V reflux. On VCUG, one patient had grade I reflux, one patients had grade II reflux, one patient had grade III, two patients had grade IV reflux and one patient had grade V reflux. One of the patients with grade 2 reflux on VCUG did not show definitive reflux on ceVUS. There was one patient with right renal agenesis, one with a single right kidney, one with left renal atrophy, one with posterior urethral valves (PUV), two with unilateral duplex collecting system, one with bilateral duplex collecting system, and one with a duplicated kidney. There was no correlation between UTI and reflux grade in our study. ceVUS showed grade 2 reflux in the lower pole of a duplicated kidney which was seen as grade I on VCUG. On the other hand, VCUG showed grade II reflux in one patient which was not detected on ceVUS. No immediate adverse events were noted in our study. No significant adverse events were observed in the 48-h follow-up interview. Two patients had transient low-grade fever, one had mild abdominal pain, and one was irritable after the procedure (Fig. 3).

The histogram displays the agreement between the grades predicted by ceVUS and VCUG. The grades estimated by ceVUS exhibited a strong correlation with VCUG, as indicated by an excellent Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.92. In addition, no statistically significant difference was observed between the ceVUS and VCUG predicted grades (p = 0.80). Similar results were obtained when analyzing the reflux detection accuracy of ceVUS and VCUG with Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.88 and p-value of 0.72. Considering VCUG as the reference standard, the diagnostic results for ceVUS were as follows: sensitivity 0.83, specificity 1, precision 1 and accuracy 0.94 (Table 3).

Discussion

Vesicoureteral reflux is a common pediatric urological condition that requires timely diagnosis and treatment to prevent irreparable kidney damage and scarring. To assess the true diagnostic value of contrast-enhanced ultrasound, it is necessary to compare it to a gold standard, which currently is voiding cystourethrography. We noted a strong correlation between the grade of reflux among the ceVUS and VCUG patients (Fig. 4).

Voiding cystourethrography involves instilling iodinated contrast into the urinary bladder. Intermittent fluoroscopy is used during bladder filling and voiding to monitor the presence or absence of reflux of contrast into the ureter and pelvicalyceal system. Urethra is imaged during voiding. It is considered the gold standard for the evaluation of vesico-ureteric reflux. The advantage is simultaneous visualization of both pelvicalyceal systems and excellent visualization of the urethra. However, since it involves radiation, intermittent fluoroscopy is performed, leading to the potential of missing transient reflux.

CeVUS has been performed in Europe for the last two decades. Lumason/Sonovue got FDA approval for intravesical use in December 2016. Since no radiation is involved, the kidneys and pelvicalyceal system are imaged for long periods of time potentially identifying more transiently recurring reflexes. Additionally, patients who have difficulty in voiding while lying down can sit up while voiding, and kidneys can be imaged from the back.

Marshner et al. [17] found that ceVUS shows a sensitivity of 95.7% with a specificity of 100%. This is similar to the findings of our study. No allergic reactions to the contrast were demonstrated in their study, similar to ours.

There has been precedent to our finding of a false negative VCUG. Ključevšek et al. [18] state that grades II and III reflux was missed by VCUG; however, detected by ceVUS. In our study, no Grade III reflux was missed by either modality. A right-sided grade II reflux seen by VCUG was not demonstrated on ceVUS. One patient was noted to have grade II reflux in the lower moiety of a duplicated collecting system which was seen as grade I on simultaneously performed VCUG. The patient had a follow-up VCUG which showed no reflux. Due to clinical concern, the patient had a PIC cystogram (positioning the instillation of contrast at the ureteral orifice), which showed grade II reflux in the lower pole moiety similar to ceVUS and was treated with deflux injection.

Piskunowicz et al. [19] demonstrated that the sensitivity of voiding cystourethrography and contrast-enhanced voiding urosonography was comparable, amounting to 88%. The negative predictive value of voiding urosonography and voiding cystourethrography was 97%, and there was no difference between both methods.

Based on the latest published guidelines of the European Association of Urology and the American Urological Association, VCUG is currently the gold standard for vesicoureteric reflux. However, in addition to the convincing results of our study that ceVUS is as good as VCUG to assess VUR, it should be also considered that the safety profile of the study is remarkably good. The contrast medium used in our study has been approved by the FDA and has generally minimal side effects.

Darge et al. [20] reported no adverse events in 27 patients who underwent ceVUS with Sonovue, followed by VCUG in the same session. No adverse events were reported by Ascenti et al. [21] in 80 patients, out of which 57 children underwent VCUG during the same session as ceVUS, and 27 children underwent VCUG within 3 days of ceVUS.

A large study by Papadopoulou et al. [22] comprising 1010 children undergoing ceVUS with SonoVue reported some kind of post procedural adverse event among 37 children. The most common adverse event was dysuria (70.3%). Other adverse events included urinary retention, transient abdominal pain, polyuria, vomiting, perineal irritation, and urinary tract infection. The minimal side effects seen in ceVUS have been reported to be predominantly due to bladder categorization and not due to contrast itself [23].

Neither the patient nor the caretakers are exposed to ionizing radiation during ceVUS. The study can be directly performed at the patient’s bedside creating a relaxed atmosphere for the patient and improving the patient-doctor relationship, especially for small children. Also, in terms of cost-effectiveness, this study is comparable to VCUG [24].

The novelty of this study lies in its focused comparison of ceVUS with VCUG for detecting moderate to severe grades of VUR (Grade II to V) in a specific pediatric population. The study provides detailed data on the effectiveness of ceVUS in identifying specific grades of VUR (II to V), which are clinically significant and often require intervention. The study adds to the body of evidence supporting the real-world application of ceVUS and its diagnostic accuracy, potentially advocating for its increased use and acceptance in routine clinical practice. It underscores the importance of reducing radiation exposure in pediatric patients, a matter of ongoing concern, by providing additional evidence supporting a non-radiating alternative [25].

The study aims to bridge the knowledge gap by providing concrete data on ceVUS's diagnostic accuracy in a real-world setting, thus supporting current guidelines based on empirical evidence. It also advocates for patient safety by reducing unnecessary radiation exposure, a critical concern in pediatric healthcare.

Limitations of the study

The small sample size and lack of randomization limit the generalizability of the findings to the larger population. Both ceVUS and VCUG were performed by the same radiologist and therefore will result in bias in interpretation due to lack of blinding. Differences in ultrasound equipment, operator skill, or interpretation of results may affect the reproducibility of ceVUS results in other settings.

Conclusion

In the cohort of 18 patients, ceVUS offered a sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 100%. Considering the unique advantages of contrast-enhanced urosonography like lack of radiation exposure, patient comfort, and intra-operative usage, contrast-entranced urosonography, can have more widespread use as a diagnostic tool for VUR.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hajiyev P, Burgu B. Contemporary management of vesicoureteral reflux. Eur Urol Focus. 2017;3:181–8.

Johnston DL, Qureshi AH, Irvine RW, Giel DW, Hains DS. Contemporary management of vesicoureteral reflux. Curr Treat Options Pediatr. 2016;2:82–93.

Ninoa F, Ilaria M, Noviello C, Santoro L, Ratsch I, Martino A, Cobellis G. Genetics of vesicoureteral reflux. Curr Genom. 2015;17:70–9.

Sargent M. Opinion. Pediatr Radiol. 2000;30:587–93.

Straub J, Apfelbeck M, Karl A, Khoder W, Lellig K, Tritschler S, Stief C, Riccabona M. Vesikoureteraler reflux. Der Urol. 2015;55:27–34.

Faizah MZ, Hamzaini AH, Kanaheswari Y, Dayang AAA, Zulfiqar MA. Contrast-enhanced voiding urosonography (ce-VUS) as a radiation-free technique in the diagnosis of vesicoureteric reflux: our early experience. Med J Malays. 2015;70:269–72.

Arena S, Iacona R, Impellizzeri P, Russo T, Marseglia L, Gitto E, Romeo C. Physiopathology of vesicoureteral reflux. Ital J Pediatr. 2016;42:103.

Skoog SJ, Peters CA, Arant BS, Copp HL, Elder JS, Hudson RG, Khoury AE, Lorenzo AJ, Pohl HG, Shapiro E, et al. Pediatric vesicoureteral reflux guidelines panel summary report: clinical practice guidelines for screening siblings of children with vesicoureteral reflux and neonates/infants with prenatal hydronephrosis. J Urol. 2010;184:1145–51.

Ascenti G, Zimbaro G, Mazziotti S, Chimenz R, Fede C, Visalli C, Scribano E. Harmonic US imaging of vesicoureteric reflux in children: usefulness of a second generation US contrast agent. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34:481–7.

Kljuˇcevšek D, Battelino N, Tomažiˇc M, Levart TK. A comparison of echo-enhanced voiding urosonography with X-ray voiding cystourethrography in the first year of life. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101:e235–9.

Mane N, Sharma A, Patil A, Gadekar C, Andankar M, Pathak H. Comparison of contrast-enhanced voiding urosonography with voiding cystourethrography in pediatric vesicoureteral reflux. Turk J Urol. 2018;44:261–7.

Radmayr C, Bogaert G, Dogan HS, Kočvara R, Nijman R, Stein R, Tekgül S. EAU guidelines on paediatric urology 2018. In: European Association of Urology Guidelines. 2018, Proceedings of the EAU Annual Congress Copenhagen, Arnhem, The Netherlands, March 2018; European Association of Urology Guidelines Office: Arnhem, The Netherlands, 2018.

Wozniak MM, Osemlak P, Pawelec A, Brodzisz A, Nachulewicz P, Wieczorek AP, Zajączkowska MM. Intraoperative contrast-enhanced urosonography during endoscopic treatment of vesicoureteral reflux in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2014;44:1093–100.

Sidhu PS, Cantisani V, Dietrich CF, Gilja OH, Saftoiu A, Bartels E, Bertolotto M, Calliada F, Clevert D-A, Cosgrove D, et al. The EFSUMB guidelines and recommendations for the clinical practice of contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in non-hepatic applications: update 2017 (short version). Ultraschall Med Eur J Ultrasound. 2018;39:154–80.

Ntoulia A, Aguirre Pascual E, Back SJ, Bellah RD, Beltrán Salazar VP, Chan PKJ, Chow JS, Coca Robinot D, Darge K, Duran C, Epelman M, Ključevšek D, Kwon JK, Sandhu PK, Woźniak MM, Papadopoulou F. Contrast-enhanced voiding urosonography, part 1: vesicoureteral reflux evaluation. Pediatr Radiol. 2021;51(12):2351–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-020-04906-8. (Epub 2021 Mar 31).

Williams G, Fletcher JT, Alexander SI, Craig JC. Vesicoureteral reflux. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:847–62.

Marschner CA, Schwarze V, Stredele R, Froelich MF, Rübenthaler J, Geyer T, Clevert DA. Evaluation of the diagnostic value of contrast-enhanced voiding urosonography about the further therapy regime and patient outcome—a single-center experience in an interdisciplinary uroradiological setting. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57(1):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57010056.PMID:33435420;PMCID:PMC7826578.

Ključevšek D, Battelino N, Tomažič M, Kersnik LT. A comparison of echo-enhanced voiding urosonography with X-ray voiding cystourethrography in the first year of life. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101(5):e235–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02588.x. (Epub 2012 Jan 27).

Piskunowicz M, Świętoń D, Rybczyńska D, Czarniak P, Szarmach A, Kaszubowski M, Szurowska E. Comparison of voiding cystourethrography and urosonography with second-generation contrast agents in a simultaneous prospective study. J Ultrason. 2016;16(67):339–47. https://doi.org/10.15557/JoU.2016.0034. (Epub 2016 Dec 30).

Darge K, Beer M, Gordjani N, et al. Contrast-enhanced voiding urosonography with the use of a 2nd generation US contrast medium: preliminary results. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34:S97.

Ascenti G, Zimbaro G, Mazziotti S, et al. Harmonic US imaging of vesicoureteric reflux in children: usefulness of a second generation US contrast agent. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34:481–7.

Papadopoulou F, Ntoulia A, Siomou E, Darge K. Contrast-enhanced voiding urosonography with intravesical administration of a second-generation ultrasound contrast agent for diagnosis of vesicoureteral reflux: prospective evaluation of contrast safety in 1,010 children. Pediatr Radiol. 2014;44(6):719–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-013-2832-9. (Epub 2014 Jan 18).

Nakamura M, Shinozaki T, Taniguchi N, Koibuchi H, Momoi M, Itoh K. Simultaneous voiding cystourethrography and voiding urosonography reveals the utility of sonographic diagnosis of vesicoureteral reflux in children. Acta Paediatr. 2003;92(12):1422–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/08035250310000617.

Mane N, Sharma A, Patil A, Gadekar C, Andankar M, Pathak H. Comparison of contrast-enhanced voiding urosonography with voiding cystourethrography in pediatric vesicoureteral reflux. Turk J Urol. 2018;44(3):261–7. https://doi.org/10.5152/tud.2018.76702. (Epub 2018 Mar 6).

Kis E, Nyitrai A, Várkonyi I, Máttyus I, Cseprekál O, Reusz G, Szabó A. Voiding urosonography with second-generation contrast agent versus voiding cystourethrography. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25(11):2289–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-010-1618-7. (Epub 2010 Aug 5).

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

The Research Ethics Committee has confirmed that no ethical approval is required.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Biswas, S., Cohen, H.L., Tipirneni-Sajja, A. et al. Comparison of contrast-enhanced voiding urosonography using second-generation contrast agents and voiding cystourethrogram. Chin J Acad Radiol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42058-024-00149-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42058-024-00149-w