Abstract

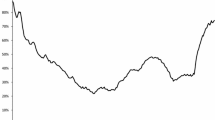

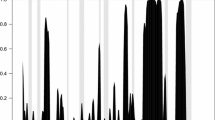

This paper shows that government debt creates a so far neglected wealth effect that has sizable effects on business cycle fluctuations. We present a channel through which governments can influence cyclical fluctuations generated by any type of shock and contribute to macroeconomic stability. We provide evidence for the United States that debt moves procyclical with output. Then, we build a Real Business Cycle model with Non-Ricardian agents and use rules to describe fiscal policy. We show that procyclical debt generates smaller fluctuations compared to countercyclical debt. The consequence is that classical Keynesian fiscal policy destabilizes the business cycle in our framework.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Bayoumi and Eichengreen (1992) use long-run restrictions in order to distinguish between demand- and supply-side shocks in the context of fiscal rules.

The appendix discusses another set of restrictions that supports our finding; also in line with the theoretical models.

The results are robust to excluding the zero-lower bound time period from 2009:Q1 onwards (using the optimal lag length of 4 quarters).

The results are robust to using a constant and using a constant and trend.

The results are robust to using up to five lags as indicated by the Akaike Information Criterion.

The discrete time version of the Blanchard–Yaari model was first developed by Frenkel and Razin (1986).

The results are robust to excluding capital adjustment costs.

Robustness checks reveal that our qualitative results are unaffected by assuming a contemporaneous relation.

Again, the automatic stabilizer component in the fiscal rules should not be mistaken with the automatic stabilizing effect of debt.

In the United States, the maturity structure of government debt is fairly short: the median number is roughly two years. Even with short- and long-term debt, keeping the assumption that demand, supply respectively is always met, the allocation between debt with different maturities does not affect overall financial wealth in t for the Non-Ricardian agent and, therefore, does not affect this channel.

As a robustness check, we directly estimate the RBC model using Bayesian methods (results available upon request). Our results presented in the following sessions are robust to using the parameter values obtained from this different approach.

First we simulate the procyclical case and then simulate the countercyclical case (independently).

To be precise, we use log-log preferences and preferences suggested by Greenwood et al. (1988) that generate a small short-run wealth effect.

References

Aghion, P., and I. Marinescu. 2008. Cyclical budgetary policy and economic growth: What do we learn from OECD panel data? NBER Chapters, in: NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2007 (22): 251–278.

Alesina, A., F. Campante, and G. Tabellini. 2008. Why Is Fiscal policy often procyclical? Journal of the European Economic Association 6 (5): 1006–1036.

Annicchiarico, B., G. Marini, and A. Piergallini. 2008. Monetary Policy and Fiscal Rules. The BE Journal of Macroeconomics: Contributions 8: 1.

Annicchiarico, B., N. Giammarioli, and A. Piergallini. 2012. Budgetary policies in a DSGE model with finite horizons. Research in Economics 66: 111–130.

Barro, R.J. 1974. Are government bonds net wealth? Journal of Political Economy 82 (6): 1095–1117.

Baxter, M., and R.G. King. 1993. Fiscal policy in general equilibrium. American Economic Review 83 (3): 315–334.

Bayoumi, T., and B. Eichengreen. 1992. Shocking aspects of European monetary unification. NBER Working Paper, No. 3949.

Blanchard, O.J. 1985. Debt, deficits, and finite horizons. Journal of Political Economy 93 (2): 223–247.

Blanchard, O.J., and R. Perotti. 2002. An empirical characterization of the dynamic effects of changes in government spending and taxes on output. Quarterly Journal of Economics 117 (4): 1329–1368.

Bohn, H. 1998. The behavior of U.S. public debt and deficits. Quarterly Journal of Economics 113 (3): 949–963.

Carvalho, C., A. Ferrero, and F. Nechio. 2016. Demographics and real interest rates: Inspecting the mechanism. European Economic Review 88: 208–226.

Christiano, L.J., M. Eichenbaum, and C.L. Evans. 2005. Nominal rigidities and the dynamic effects of a shock to monetary policy. Journal of Political Economy 113 (1): 1–45.

DeLong, J.B., and L.H. Summers. 1986. The Changing cyclical variability of economic activity in the United States. In The American business cycle: Continuity and change, ed. R.J. Gordon. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Favero, C. A., 2003. How do European monetary and fiscal authorities behave? In Buti (ed.): Monetary and Fiscal Policies in EMU. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Frenkel, J.A., and A. Razin. 1986. Fiscal policies in the world economy. Journal of Political Economy 94 (3): 564–594.

Galí, J. 1994. Government size and macroeconomic stability. European Economic Review 38: 117–132.

Gordon, D. B., and E. M. Leeper. 2005. Are countercyclical fiscal policies counterproductive? NBER Working Paper, No. 11869.

Greenwood, J., Z. Hercowitz, and G.W. Huffman. 1988. Investment, capacity utilization, and the real business cycle. American Economic Review 78 (3): 402–417.

King, R. G., and S. T. Rebelo. 1999. Resuscitating real business cycles. In: Taylor, J. B. and Woodford, M. (eds.), Handbook of Macroeconomics, Vol. 1, issue 1, Chap. 14, 927–1007.

Leith, C., and L. von Thadden. 2008. Monetary and fiscal policy interactions in a new Keynesian model with capital accumulation and non-Ricardian consumers. Journal of Economic Theory 140 (1): 279–313.

Leith, C., and S. Wren-Lewis. 2000. Interactions between monetary and fiscal policy rules. Economic Journal 110 (462): C93–108.

Leeper, E.M., and S.-C.S. Yang. 2008. Dynamic scoring: Alternative financing schemes. Journal of Public Economics 92 (1–2): 159–182.

Leeper, E.M., M. Plante, and N. Traum. 2010a. Dynamics of fiscal financing in the United States. Journal of Econometrics 156 (2): 304–321.

Leeper, E.M., T.B. Walker, and S.-C.S. Yang. 2010b. Government investment and fiscal stimulus. Journal of Monetary Economics 57: 1000–1012.

Mehra, R., and E.C. Prescott. 1980. Recursive competitive equilibrium: The case of homogeneous households. Econometrica 48 (6): 1365–1379.

Richter, A. 2014. Finite lifetimes, long-term debt and the fiscal limit. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 51: 180–203.

Sims, C. 2002. Solving linear rational expectations models. Computational Economics 20: 1–20.

Smets, F., and R. Wouters. 2002. Openness, imperfect exchange rate pass-through and monetary policy. Journal of Monetary Economics 49 (5): 947–981.

Weil, P. 1989. Overlapping families of infinitiely-lived agents. Journal of Public Economics 38: 183–198.

Yaari, M. 1965. Uncertain lifetime, life insurance and the theory of the consumer. Review of Economic Studies, 32 (2): 137–150.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

I am highly indebted to Gadi Barlevy, Marco Bassetto, Jeff Campbell, Larry Christiano, Marty Eichenbaum, Ester Faia, Alejandro Justiniano, Keith Kuester, Christian Matthes, Christian Merkl, Olaf Posch, and Frank Schorfheide for very helpful comments and suggestions. In addition, I thank seminar participants at the Chicago FED, the Banque de France, the University of Hamburg, the 2013 annual meeting of the Society for Computational Economics in Vancouver, the 4th conference on Recent Developments in Macroeconomics in Mannheim, the 18th T2M Conference in Lausanne, and the 4th SEEK Conference in Mannheim. Furthermore, I am deeply thankful to the Research Department at the Chicago FED for the opportunity to conduct a research visit, the hospitality throughout my stay, and the countless beneficial conversations. All remaining errors are my own.

Appendix

Appendix

VECM

In this section we offer an additional set of restrictions that support our findings of procyclicality of debt:

The restrictions on the long-run impact matrix, \(\mathbf {C}\left( 1\right) \mathbf {B}\), imply that the interest rate has no long-run effect on output, debt has no long-run effect on the interest rate, and government consumption has no long-run effect on government investment. Long-run neutrality of monetary policy supports the first restriction. The second restriction implies that the central bank does not (at least not quantitatively important) to changes in government debt. Finally, the government does not change government investment expenditures due to changes in government consumption. This assumption implies that the two components—consumption and investment—have no effect on each other in the long-run. Government consumption has a rather short-term motivation while government investment are thought to create slow-moving long-run effects.

Further, we impose the following restrictions on the contemporaneous impact matric, \(\mathbf {B}\): the interest rate has no effect on the fiscal variables. In the short-run fiscal policy is pinned down and movements in the interest rate do not affect (at least not significantly) government plans. Government consumption does not affect the interest rate and government investment. Monetary policy typically reacts to changes in output, the inflation rate, and (potentially) asset prices. Usually, it does not react to movements in fiscal policy. Government investment does affect debt and taxes. Government investment projects are associated with various (implementation) delays. Therefore, one can argue that it will only affect debt and taxes because of the financing needs. Finally, taxes do affect debt but do not affect other variables in the short-run due to implementation delays.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wesselbaum, D. Procyclical Debt as Automatic Stabilizer. J. Quant. Econ. 18, 81–102 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40953-019-00174-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40953-019-00174-y