Abstract

Teacher self-efficacy has been shown to be a protective factor for teachers’ feelings of burnout, whereas ethnic prejudice might be a risk factor. Ethnic minority students are often perceived negatively and are associated with low motivation, a large number of classroom disruptions, and discipline problems. Prejudice toward these students can impact teaching practices and create a negative environment, leading to stressful situations. In the current study, we explored the associations between different teacher self-efficacy dimensions and ethnic prejudice in three dimensions of burnout in a sample of 84 preservice and inservice teachers from Italy and Germany. Results showed that teacher self-efficacy in classroom management one factor that protects teachers against emotional exhaustion and reduced personal accomplishment. However, teacher self-efficacy did not have a significant impact on feelings of depersonalization, which was mainly predicted by prejudice toward ethnic minorities. This study lays the base for potential interventions targeting the reduction of ethnic prejudice among teachers and preservice teachers. The findings suggest that addressing ethnic prejudice may be valuable, but further research is crucial to comprehensively investigate the multifaceted outcomes of possible interventions and their potential impact on both teachers and students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Prejudice holds a substantial influence within the education context, especially concerning teachers’ perspectives on ethnic minority students. The aim of this study was to investigate the roles that teachers’ prejudice toward ethnic minority students and self-efficacy play in teachers’ feelings of burnout.

Teachers are vulnerable to suffering from burnout, which often leads to early retirement or to teacher turnover. Burnout and stress factors are not only work- and teacher-related but also student-related. Aggressive student behavior (Wettstein et al., 2023), a large number of classroom disruptions (Dicke et al., 2014), and low student motivation (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2020) are important factors for determining teachers’ stress and feelings of burnout. Teachers tend to believe that ethnic minority students show low motivation, cause higher number of classroom disruptions, and have discipline problems (Gregory et al., 2010)—even when such beliefs are inaccurate. Teachers also have low expectations of the extent to which ethnic minority students are teachable. Such beliefs and expectations might stem from prejudice and might be found in the student-related factors of teachers’ burnout.

Modern prejudice is conceptualized with three different indicators (Akrami et al., 2000). People expressing modern prejudice deny that discrimination still exists, thus promoting egalitarian beliefs and feeling resentful about the special support of ethnic minorities (Akrami et al., 2000). They have a poor understanding of ethnic minorities’ needs. Prejudice seems to impact teaching practices (Kumar & Lauermann, 2018), which can lead to a negative climate. Teaching in a negative climate can be stressful and promotes prejudiced perceptions of student-related factors of burnout, such as low student motivation and large discipline problems.

Although burnout is a syndrome that is characterized by multiple symptoms, research has specified three psychological dimensions that are part of burnout (Maslach & Jackson, 1981). Reduced personal accomplishment refers to decreased achievement even though the teacher feels that they are trying very hard (Maslach & Jackson, 1981). Emotional exhaustion is accompanied by feelings of low energy and depleted resources (Maslach & Jackson, 1981). The last dimension is depersonalization, which is indicated by a high level of cynicism and disinterest in one’s work (Maslach et al., 2001).

With respect to teacher-related factors, self-efficacy beliefs have been shown to protect teachers from burnout. Teacher self-efficacy is defined as teachers’ beliefs that their pedagogical actions can promote student development (Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, 2001) and is based on Bandura’s (2001) social cognitive theory. This framework underscores how individuals’ beliefs, behavior, and environmental factors interact, offering insights into the interplay between self-efficacy, prejudice, and burnout. Self-efficacy beliefs, which refer to one’s perceived ability to accomplish tasks, shape behaviors and responses (Bandura, 2001). Social cognitive theory also recognizes the importance of cognitive processes, such as beliefs and perceptions, in influencing behavior (Bandura, 2001), which further aligns our understanding how prejudice and self-efficacy can affect teachers’ responses to various stressors.

Teacher self-efficacy is divided into three dimensions, which refer to teacher self-efficacy in student engagement, classroom management, and instructional strategies (Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, 2001). Student engagement is related to teachers’ subjective belief that they are able to motivate even unmotivated students and to get students engaged in the lesson (Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, 2001). This dimension has been linked to lower feelings of emotional exhaustion (Wang et al., 2015). Classroom management indicates the use of strategies to maintain social order, and instructional strategies means adaptive teaching (Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, 2001). Research has shown that lower self-efficacy in classroom management is associated with high cynicism and a high lack of personal accomplishment (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2020). Finally, there is a strong negative relation between self-efficacy in instructional strategies and cynicism toward students (Khani & Mirzaee, 2015).

Feelings of burnout and teacher self-efficacy can be impacted high cultural diversity in the classroom. Teachers and preservice teachers had lower self-efficacy beliefs with respect to their teaching and higher feelings of burnout when they were confronted with a school with a large proportion of ethnic minority students (Glock et al., 2019). This connection may be rooted in teachers perceiving ethnic minority students as more challenging, potentially leading to diminished confidence in their instructional effectiveness (Amitai et al., 2020). Stereotypes and prejudice towards ethnic minority students may lead teachers to perceive them as having diminished motivation (Agirdag et al., 2013) and hold lower expectations for their academic performance (Costa et al., 2022), and anticipate more disciplinary problems (Gregory et al., 2010). These perceptions, in turn, could contribute to a decrease in teacher self-efficacy. In fact, teachers with high levels of ethnic prejudice show lower self-efficacy (Glock & Kleen, 2019) and experience more feelings of burnout (Costa et al., 2023). This can occur if teachers do not feel prepared to handle the needs of ethnic minority students (Gutentag et al., 2018).

In the Italian schools, the most represented—and disadvantaged—ethnic minority student groups come from Romania, Morocco, and Albania, while in Germany the majority of ethnic minority is represented by Turkish students.

In both Italian and German schools, there is a predominantly non-minority teaching staff, serving increasingly diverse student populations. For instance, according to the OECD (2019b), students with a minority ethnic background make up 17% of the classroom demographic in Italy and 28.1% in Germany. However, the teaching workforce in both countries remains largely homogeneous, with a significant majority of teachers belonging to the ethnic majority. For instance, in Germany, around 13% of teachers have a migration background (Mediendienst Integration, 2023). Similarly, in Italy, the percentage of teachers with a foreign background is significantly lower than that of students with migrant origins, indicating a notable ethnic disparity between the teaching staff and the student population (OECD, 2019a).

Considering the presented literature, we expected the three different dimensions of burnout to be differentially predicted by the three different dimensions of teacher self-efficacy as well as by prejudice.

Method

Participants

A convenience sample of 84 preservice and inservice teachers from Italy and Germany participated in this study. In the Italian subsample, 27 (8 male, 19 female) were inservice and 19 were preservice teachers (1 male, 18 female). The Italian inservice teachers were on average 46.88 years old (SD = 10.32) with a mean teaching experience of 17.44 years (SD = 12.42). Preservice teachers had a mean age of 26.27 (SD = 6.22) and a mean teaching experience of 2.25 years (3.61). A total of 38 preservice teachers participated (7 male, 31 female) from Germany with a mean age of 25.17 (SD = 3.49) and a mean teaching experience of 0.65 years (SD = 0.88). None of the participants indicated that they had an ethnic minority background.

Materials

Maslach Burnout Inventory

To assess participants’ feelings of burnout, we used the German (Enzmann & Kleiber, 1989) and Italian translations (Sirigatti et al., 1988) of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI; (Maslach & Jackson, 1981). This questionnaire considers the three dimensions of burnout and measures emotional exhaustion with nine items (Cronbach’s α = 0.81 for the Italian version; Cronbach’s α = 0.89 for the German version))Footnote 1. One example is “I feel frustrated by my job”). Reduced personal accomplishment is assessed with eight items (Cronbach’s α = 0.76 for the German version as well as for the Italian version); e.g., “I feel very energetic”). The last dimension is depersonalization, which is assessed with five items (Cronbach’s α = 0.77 for the Italian version, Cronbach’s α = 0.63 for the German version; e.g., “I don’t really care what happens with some students”). Participants indicated their agreement with the items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (do not agree at all) to 5 (totally agree).

Teacher Self-Efficacy

We used the Italian translation (Biasi et al., 2014) and German adaptation (Pfitzner-Eden et al., 2014) of the teacher self-efficacy scale (Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, 2001). It measures teacher efficacy in classroom management with eight items (Cronbach’s α = 0.90 for the Italian version; Cronbach’s α = 0.87 for the German version; e.g., “How much can you do to control disruptive behavior in the classroom?”). Another eight items refer to student engagement (Cronbach’s α = 0.88 for the Italian version; Cronbach’s α = 0.78 for the German version; e.g., “How much can you do to get students to believe they can do well in schoolwork?”). The last dimension is teacher efficacy in instructional strategies, which is measured with eight items (Cronbach’s α = 0.87 for the Italian version; Cronbach’s α = 0.77 for the German version;; e.g., “To what extent can you use a variety of assessment strategies?”). The German translation has shown high construct validity, even for the three scales (Pfitzner-Eden et al., 2014) and the Italian translation of the scale also has shown good validity (Biasi et al., 2014). Participants indicated their agreement with the items on a 9-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (do not agree at all) to 9 (totally agree).

Modern Racial Prejudice Scale

We employed Akrami et al.‘s (2000) scale, which has already been tested in the Italian context (Gattino et al., 2011). This scale has a good discriminant and construct validity (Akrami et al., 2000), even the Italian version (Gattino et al., 2011). The translation process to create a German version of the scale, involved two native German speakers with expertise in the subject matter. We adopted a forward translation approach, rendering the English items into German. Subsequently, a back translation was performed to ensure linguistic accuracy. The scale uses nine items (Cronbach’s α = 0.66 for the Italian version; Cronbach’s α = 0.89 for the German version; e.g., “It is easy to understand immigrants’ demands for equal rights”). However, even we ensured that the content of the items matched the original items, we have no indication of the validity of this scale in German. Participants indicated their agreement with the items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (do not agree at all) to 5 (totally agree).

Demographic Questionnaire

We assessed participants’ gender, age, and professional status. Their teaching experience was assessed in months.

Procedure

Data collection occurred via the online version of the Inquisit software. Preservice teachers were contacted through their academic programs, while inservice teachers were engaged through prior contact with head teachers.

First, the participants gave informed consent. Then they were provided with the different questionnaires: first, the burnout scale, then the teacher self-efficacy scale, and finally, the prejudice questionnaire. In the end, the participants filled out the demographic questionnaire, were thanked, and debriefed.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

We first investigated whether there were differences between the Italian and the German (preservice) teachers (see Table 1). First, we computed a mixed ANOVA using participants’ country (Italy vs. Germany) as a between-subjects factor and the different burnout dimensions (personal accomplishment vs. Emotional exhaustion vs. Depersonalization) as a within-subjects factor. This ANOVA yielded no main effect of country and no interaction between country and the burnout dimensions. The mixed ANOVA using participants’ country as a between-subjects factor and the different teacher self-efficacy dimensions as a within-subjects factor showed a different picture. The main effect of country and the interaction between country and the self-efficacy dimensions were significant, all indicating that the Italian sample felt higher self-efficacy. For prejudice, there was no difference between the two countries.

We conducted the same analyses with teacher status as factor. For the MBI, there was no main effect of status and no interaction effect. The same ANOVA on teacher self-efficacy, yielded a significant main effect for teacher status, showing that the inservice teachers felt more efficacious than the preservice teachers. The interaction was not significant. For prejudice, there was no difference between inservice and preservice teachers. Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the participants on the different variables. The preliminary analyses have not been the focus of our research, and we did not make any sample size considerations beforehand. However, a power analysis for the mixed measures ANOVAs showed that we were able to detect an effect size of ηp2 = 0.02 with a power of 0.80. When considering Cohen’s d and the t tests, we had very low power and would have found an effect of d = 30, with a power 0.28.

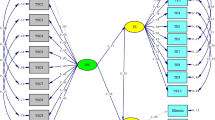

Multiple Regression

In a first step, we calculated the correlations between the different variables (see Table 3). As some correlations were considerably high, we investigated multicollinearity by computing the VIF and tolerance, following the suggestions formulated by Cohen et al. (2003). No VIF value exceeded 10 (highest VIF = 4.63), and no tolerance value was lower than 0.10 (lowest tolerance value = 0.22), values that are not optimal but also do not indicate any serious problems (Cohen et al., 2003). Then we computed three different multiple regression analyses (see Table 4) to predict the three dimensions of burnout using the three dimensions of teacher self-efficacy and prejudice as predictors. Even though preliminary analyses showed that both status of teachers and country had an effect on teacher self-efficacy, we only added country as a control variable, as this effect size was higher than this of teacher status.

In this study, the multiple regression predicting personal accomplishment showed that teacher self-efficacy with respect to classroom management and student engagement were significant predictors. Teachers’ feelings of accomplishment were lower when teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs were higher. Exhaustion was predicted by teacher self-efficacy with respect to classroom management. Higher teacher self-efficacy beliefs went along with lower emotional exhaustion. Finally, the higher teachers’ prejudice was, the higher their feelings of depersonalization were. Here, teacher self-efficacy was not a significant predictor.

Discussion

The finding that teachers’ self-efficacy plays an important role in their feelings of burnout is not new. Nonetheless, research investigating the roles of the different teacher self-efficacy dimensions in the three dimensions of burnout is sparse. In line with previous research (Dicke et al., 2014), our study showed that teacher self-efficacy in classroom management is one main factor. Student misbehavior is one of the key sources of teacher stress; in particular, aggressive student behavior is related to exhaustion (Wettstein et al., 2023). Hence, feeling high self-efficacy in handling various student behaviors as part of an effective classroom management strategy seems to protect teachers from emotional exhaustion and reduced personal accomplishment. Low student motivation is most strongly related to reduced personal accomplishment (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2020). Thus, teacher self-efficacy in student engagement might help teachers protect themselves against these feelings.

Teacher self-efficacy was not associated with feelings of depersonalization, which were primarily linked to prejudice toward ethnic minority people, as shown by the correlation analysis. Although research has consistently shown that teachers’ feelings of burnout are related to their perceptions of the ethnic composition of the school (Glock et al., 2019) and that negative implicit prejudice toward ethnic minority students increases teachers’ feelings of burnout (Costa et al., 2023), our study shed more light on these relationships. Most interestingly, the higher teachers’ prejudice, the higher their depersonalization, and this effect occurred independent of teacher self-efficacy. Nonetheless, the correlational analyses also showed that teacher self-efficacy was lower when their prejudice was higher. Prejudice toward ethnic minority students seems to be particularly important: teachers with lower levels of prejudice tend to experience lower risks of burnout, as evidenced by higher self-efficacy and lower depersonalization. These findings are also in line with previous research that has shown that burnout is higher among teachers who view ethnic minority students as a problem (Gutentag et al., 2018).

Prejudice did not show a significant correlation with the other dimensions of burnout. Prejudice involves attitudes and beliefs directed towards others, and this resonates with the dimensions of depersonalization, that represents a detachment and negative attitude towards others in the work context (Maslach et al., 2001). Accordingly, the lack of correlation with the other dimensions can be attributed to their divergent directions– prejudice focuses on attitudes and beliefs towards others, while the other two dimensions of burnout, emotional exhaustion and reduced personal accomplishment, primarily concern the individual’s own experiences and self-perceptions.

However, while prejudice might primarily impact the depersonalization dimension of burnout, its influence can still have cascading effects on overall teacher well-being, as the interconnected nature of these dimensions means that changes in one area can have repercussions in others and in their general well-being. Our findings suggest that interventions targeting teachers’ and preservice teachers’ prejudice could benefit both ethnic minority students and the educators themselves. In the context of increased globalization, classrooms in both Italy and Germany reflect a significant proportion of students with a minority ethnic background (OECD, 2019b). However, perceiving this demographic shift as a challenge, rather than an opportunity, can contribute to heightened feelings of burnout and reduced self-efficacy among teachers (Gutentag et al., 2018). Given the evolving social landscape in Europe, characterized by heightened migration and multiculturalism within classrooms, it is crucial to underscore to teachers the importance of addressing these matters. The ultimate aim is to cultivate an environment that reduces prejudice, benefiting both students and educators.

There are some limitations that should be kept in mind. First and above all, our sample comprised teachers and preservice teachers from two different countries. Although the countries do not differ profoundly in their proportion of ethnic minority students and their school systems (Eurydice, 2022), which led us not to expect differences between the teachers in Germany and Italy, the Italian preservice and inservice teachers had higher teacher self-efficacy beliefs. One could argue that these differences were due to German inservice teachers who were not included in the sample. However, research on teacher self-efficacy has not provided profound differences that depend on expertise (Glock & Kleen, 2019). We added country as a control variable and still found effects of teacher self-efficacy. Nonetheless, future research might take a closer look into the differences between the teachers in these two countries, particularly into their teacher education programs, which seem to equip Italian teachers with stronger self-efficacy beliefs.

As we did not expect differences between the two countries, we did not make sample size considerations beforehand, and it might be that we were not able to detect all differences between the two countries because of lacking power. This might be particularly true for the prejudice measure, for which the difference between the Italian and German sample had a small effect size. Although one could argue, that this was only a small effect, we know that small effect in prejudice can nevertheless have profound consequences for discrimination (Greenwald et al., 2015). Moreover, due to the small and heterogenous sample size and the limited scope of the study, the results may not be generalizable to the broader population. Hence, in future research, such power considerations should be included.

We did not employ a specific measure of self-efficacy for the teaching of ethnic minority students. Such a measure might be able to provide more fine-grained findings on the relationships between teacher self-efficacy, burnout, and the handling of ethnically diverse classrooms. Additionally, prejudice was not assessed on an implicit level. Certainly, this introduces a challenge associated with social desirability, as individuals may tend to respond to explicit questionnaires in a manner they perceive as socially acceptable, particularly when addressing sensitive topics such as ethnic prejudice (Dovidio et al., 2009). To date, various methods exist for testing ethnic attitudes at an implicit level, albeit with their own set of limitations (for a more in-depth overview of methods for measuring teachers’ implicit attitudes toward students from minority groups, see the following review and meta-analysis, respectively, Costa et al., 2021; Pit-ten Cate & Glock, 2019). Previous research has already shown that implicit bias toward ethnic minority students is related to teacher burnout (Costa et al., 2023), but further research is needed to enhance the understanding of the impact of prejudice.

It is important to note that a potential limitation of our study is that we did not directly inquire about teachers’ personal experiences in instructing ethnic minority students within their own classrooms. This aspect should be addressed in future research, as it could provide valuable insights on how teachers’ prejudice might be influenced by their previous interactions with ethnic minority students.

We assessed only the three theoretical dimensions of burnout and did not include outcome measures such as hair cortisol (Wettstein et al., 2023) or the intention to leave the profession (Maslach et al., 2001) or university. It would be interesting to investigate the relationships that teacher self-efficacy and prejudice have with such burnout-related outcome variables. Relatedly, burnout is a complex phenomenon and in future research, it will be necessary to include more control variables which are related to prejudice, for instance teacher gender or school type (Glock & Klapproth, 2017).

Conclusion

Despite all limitations, our study provides new insights into how teacher self-efficacy, the aspects of burnout and prejudice is related. Most importantly, prejudice contributes to depersonalization, which is particularly threatening the teacher student relationship (Milatz et al., 2015). Simultaneously, self-efficacy decreases with higher prejudice, which is not only detrimental for students but also for teacher well-being. Future research should investigate the role of teacher prejudice more deeply to understand coping strategies that help teachers manage ethnically heterogeneous classrooms, ultimately enhancing teacher well-being. Interventions targeting prejudice among teachers and preservice teachers could benefit both educators and ethnic minority students. In multicultural classrooms, particularly in Italy and Germany, addressing and reducing prejudice is essential for fostering an inclusive and supportive educational environment that enhances teacher well-being and effectiveness.By demonstrating that higher prejudice is associated with increased depersonalization and lower self-efficacy, this research underscores the importance of addressing prejudice in teacher education programs. The dual focus on self-efficacy and prejudice offers a unique perspective on mitigating burnout and promoting teacher well-being, especially in multicultural educational settings.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Notes

All reliability measures have been computed from our sample.

References

Agirdag, O., Van Houtte, M., & Van Avermaet, P. (2013). School segregation adn self-fulfilling prophecies as determinants of academic achievement in Flanders. In S. De Groof & M. Elchardus (Eds.), Early school leaving & youth unemployment (pp. 46–74).

Akrami, N., Ekehammar, B., & Araya, T. (2000). Classical and modern racial prejudice: A study of attitudes toward immigrants in Sweden. European Journal of Social Psychology, 30(4), 521–532.

Amitai, A., Vervaet, R., & Van Houtte, M. (2020). When teachers experience burnout: Does a multi-ethnic student population put out or spark teachers’ fire? Pedagogische Studien, 97(2), 125–145.

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

Biasi, V., Domenici, G., Patrizi, N., & Capobianco, R. (2014). Teacher self-efficacy scale (Scala Sull’auto-efficacia Del Docente–SAED): Adattamento E validazione in Italia. Journal of Educational Cultural and Psychological Studies, 10, 485–509. https://doi.org/10.7358/ecps-2014-010-bias

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Costa, S., Langher, V., & Pirchio, S. (2021). Teachers’ implicit attitudes toward ethnic minority students: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(712356). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.712356

Costa, S., Pirchio, S., & Glock, S. (2022). Teachers’ and preservice teachers’ implicit attitudes toward ethnic minority students and implicit expectations of their academic performance. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 89, 56–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2022.05.006

Costa, S., Pirchio, S., Shevchuk, A., & Glock, S. (2023). Does teachers’ ethnic bias stress them out? The role of teachers’ implicit attitudes toward and expectations of ethnic minority students in teachers’ burnout. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 93, 101757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2023.101757

Dicke, T., Marsh, H. W., Parker, P. D., Kunter, M., Schmeck, A., & Leutner, D. (2014). Self-efficacy in classroom management, classroom disturbances, and emotional exhaustion: A moderated mediation analysis of teacher candidates. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(2), 569–583. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035504

Dovidio, J. F., Kawakami, K., Smoak, N., & Gaertner, S. L. (2009). The nature of contemporary racial prejudice: Insight from implicit and explicit measures of attitudes. In R. E. Petty, R. H. Fazio, & P. Brinol (Eds.), Attitudes: Insights from the new implicit measures (pp. 165–192). Psychology.

Enzmann, D., & Kleiber, D. (1989). Helfer-Leiden: Stress und Burnout in psychosozialen Berufen [Aiders-Suffering: Stress and burnout in psycho-social occupations ]. Asanger.

Eurydice (2022). The structure of the European education systems 2022/2023: schematic diagrams (P. Birch (Ed.)). Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2797/21002

Gattino, S., Miglietta, A., & Testa, S. (2011). The Akrami, Ekehammar, and Araya’s classical and modern racial prejudice scale in the Italian context. Tpm, 18(1), 31–47. http://www.tpmap.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/18.1.3.pdf

Glock, S., & Klapproth, F. (2017). Bad boys, good girls? Implicit and explicit attitudes toward ethnic minority students among elementary and secondary school teachers. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 53(September 2016), 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2017.04.002

Glock, S., & Kleen, H. (2019). Implicit and explicit measures of teaching self-efficacy and their relation to cultural heterogeneity: Differences between preservice and in-service teachers. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 19(S1), 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12475

Glock, S., Kleen, H., & Morgenroth, S. (2019). Stress among teachers: Exploring the role of Cultural Diversity in Schools. Journal of Experimental Education, 87(4), 696–713. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2019.1574700

Greenwald, A. G., Banaji, M. R., & Nosek, B. A. (2015). Statistically small effects of the Implicit Association Test can have societally large effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(4), 553–561. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000016

Gregory, A., Skiba, R. J., & Noguera, P. A. (2010). The achievement gap and the discipline gap: Two sides of the same coin? Educational Researcher, 39, 59–68. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X09357621

Gutentag, T., Horenczyk, G., & Tatar, M. (2018). Teachers’ approaches toward Cultural Diversity Predict Diversity-Related Burnout and Self-Efficacy. Journal of Teacher Education, 69(4), 408–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487117714244

Khani, R., & Mirzaee, A. (2015). How do self-efficacy, contextual variables and stressors affect teacher burnout in an EFL context? Educational Psychology, 35(1), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2014.981510

Kumar, R., & Lauermann, F. (2018). Cultural beliefs and instructional intentions: Do experiences in teacher education institutions matter? American Educational Research Journal, 55(3), 419–452. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831217738508

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behavior, 2, 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422. https://doi.org/0066-4308/01/0201-0397$14.00

Mediendienst Integration (2023). Wie viele Lehrer*innen haben einen Migrationshintergrund? Schule. https://mediendienst-integration.de/integration/schule.html

Milatz, A., Lüftenegger, M., & Schober, B. (2015). Teachers’ relationship closeness with students as a resource for teacher wellbeing: A response surface analytical approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(DEC), 1949. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01949

OECD (2019a). Italy - Nota Paese - Risultati TALIS 2018. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/1d0bc92a-en

OECD (2019b). The road to integration: Education and Migration. In OECD Reviews of Migrant Education. https://doi.org/10.1787/d8ceec5d-en

Pfitzner-Eden, F., Thiel, F., & Horsley, J. (2014). An adapted measure of teacher self-efficacy for Preservice teachers: Exploring its Validity across two countries. Zeitschrift Für Pädagogische Psychologie, 28(3), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1024/1010-0652/A000125

Pit-ten Cate, I. M., & Glock, S. (2019). Teachers’ implicit attitudes toward students from different social groups: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2832. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02832

Sirigatti, S., Stefanile, C., & Menoni, E. (1988). Per Un Adattamento Italiano Del Maslach Burnout inventory (MBI). Bollettino Di Psicologia Applicata, 187–188, 33–39.

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2020). Teacher burnout: Relations between dimensions of burnout, perceived school context, job satisfaction and motivation for teaching. A longitudinal study. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 26(7–8), 602–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2021.1913404

Tschannen-Moran, M., & Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17, 783–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1

Wang, H., Hall, N. C., & Rahimi, S. (2015). Self-efficacy and causal attributions in teachers: Effects on burnout, job satisfaction, illness, and quitting intentions. Teaching and Teacher Education, 47, 120–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.12.005

Wettstein, A., Jenni, G., Schneider, S., Kühne, F., Holtforth, M., & Marca, L., R (2023). Teachers’ perception of aggressive student behavior through the lens of chronic worry and resignation, and its association with psychophysiological stress: An observational study. Social Psychology of Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-023-09782-2

Funding

This research was not funded by any external sources.

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi Roma Tre within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

This research received ethical approval from [masked] University’s ethical committee.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in this study. Participants were provided with information about the study and agreed to participate voluntarily.

Consent to Publication

The authors have obtained consent to publish the research findings and data from all individuals that have participated to the study.

Competing Interests

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Glock, S., Costa, S. Predicting Teachers’ Burnout from Self-Efficacy Dimensions and Prejudice Toward Ethnic Minorities. Contemp School Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-024-00515-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-024-00515-6