Abstract

Background

As part of the risk-management plan (RMP) for aflibercept, materials have been developed to educate physicians in Canada on the key safety information and safe use for aflibercept.

Objective

The objectives of this study were to assess whether physicians in Canada received and reviewed the aflibercept educational materials (i.e. vial preparation instruction card, intravitreal injection procedure video, and product monograph) and to evaluate their knowledge of key safety information.

Methods

Retinal specialists and ophthalmologists who prescribe and/or administer aflibercept were recruited to complete a survey. Physicians could complete and return a paper questionnaire by mail or complete the questionnaire online via a study website.

Results

Of the 308 physicians invited to participate in the survey, 95 (31%) completed the questionnaire. Nearly all physicians (98%) reported receiving at least one of the educational materials. The proportion of correct responses to individual questions on storage and preparation of aflibercept ranged from 54 to 98%. Physician knowledge was high on the recommended dose of aflibercept (91%), dose preparation (91–96% on individual items), and dosing guidelines (75–95% on individual items). Most physicians knew the contraindications for aflibercept (89%) and that aflibercept should not be used in pregnancy unless clearly indicated by medical need in which benefits outweigh risks (60%); 21% responded more conservatively that aflibercept should never be used in pregnancy. Knowledge was high for most questions about injection procedures (91–99% on individual items); however, fewer physicians (24%) correctly reported that the eye should be covered with a sterile drape. Knowledge was high for possible side effects (89–100% on individual items) and actions to take in relation to the potential for increased intraocular pressure (86–93% on individual items).

Conclusion

Nearly all physicians (98%) reported having received the product monograph, and most (82%) reported having received the vial preparation instruction card; nearly half (46%) reported having received the intravitreal injection procedure video. Physicians’ knowledge of the most important topics was high. Knowledge varied for topics that are less frequently encountered (e.g. use in women of childbearing potential) and for recommendations that are not standard medical practice in Canada (e.g. use of sterile drape).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Canadian physicians’ receipt of aflibercept educational materials and knowledge of key safety information for aflibercept were evaluated in a survey. |

Among 95 physician respondents, knowledge was high for recommended dose (91%), dose preparation (91–96%), dosing guidelines (75–95%), contraindications (89%), avoidance of aflibercept during pregnancy (60%), possible side effects (89–100%), and the potential for increased intraocular pressure (86–93%). |

Knowledge of injection procedures was high (91–99%), but only 24% of physicians correctly reported that the eye should be covered with a sterile drape (which is not standard medical practice in Canada). |

1 Introduction

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-induced neovascularization is a mechanism common to several vascular eye diseases. VEGF plays a major role in the development of abnormal vasculature characteristic of the neovascular (“wet”) form of age-related macular degeneration (wAMD), a leading cause of vision loss in older adults [1]. Abnormal secretion of VEGF also can stimulate vascular growth secondary to retinal vein occlusion [including central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) and branch retinal or hemiretinal vein occlusion], potentially leading to neovascularization and, eventually, to macular edema and severe visual loss [2]. Diabetic macular edema (DME), an advanced complication accounting for much of the vision loss associated with diabetic retinopathy, may cause chronic microvascular damage and increased intraocular secretion of VEGF.

Anti-VEGF therapies have shown efficacy in treating wAMD [3,4,5,6], CRVO macular edema [7], and DME [8]. The intravitreal injection aflibercept (Eylea; Bayer AG) was initially approved in Canada for the treatment of wAMD in November 2013, and later was approved for visual impairment due to macular edema secondary to CRVO (in 2014) or branch retinal vein occlusion (in 2015), DME (in 2014), and myopic choroidal neovascularization (in 2017) [9]. However, intravitreal injections, including anti-VEGF therapies, have been associated with some complications, including endophthalmitis, transient increases in intraocular pressure, glaucoma, traumatic cataract, and retinal and vitreous detachment. Less serious and more common complications include conjunctival hemorrhage, vitreous floaters, and eye pain [5, 10]. Some reports have noted the potential for systemically administered anti-VEGF therapies to increase risk of arterial thromboembolic events [9,10,11].

A risk management plan (RMP) is in place to describe, monitor, and minimize known and potential safety issues associated with aflibercept. As part of the RMP, the marketing authorization holder developed materials to educate physicians in Canada on key safety information and safe use of aflibercept. The objective of this study was to survey physicians who prescribe aflibercept in Canada to determine whether they had received the educational materials and to assess their knowledge and understanding of the key safety information therein. A similar study was conducted to evaluate physician knowledge of the key safety information for aflibercept in Europe [20].

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design and Sample

This study was an observational, cross-sectional survey study of knowledge, understanding, and self-reported behavior among a target sample of 50 physicians with recent aflibercept experience in Canada. Respondents were a sample of convenience, based on the number of physicians known to prescribe aflibercept in Canada. A significantly larger study size would not have been feasible given the relatively small number of known aflibercept prescribers in Canada. The study was conducted in line with the Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices [12] and complied with all local regulatory and ethical requirements. Exemption from review was granted by the RTI International Institutional Review Board. All participants provided informed consent.

The aflibercept educational materials initially were distributed by mail on hard copy after the initial approval of aflibercept for the wAMD indication in December 2013. The materials then were distributed again after the approval of additional indications for aflibercept in December 2015. Specifically, the materials were distributed by field forces, with the vial preparation instruction card on hard copy and the intravitreal injection procedure video on a USB drive.

Participants were retinal specialists and ophthalmologists practicing in Canada who had prescribed or administered aflibercept to at least one patient in the past 6 months. The survey was initiated after a sufficient period to allow prescribers to have received the educational materials and use the information in practice (approximately 3 months). All physicians on a prescriber list, believed by the marketing authorization holder to include most physicians prescribing and/or administering aflibercept in Canada, were invited to participate in the study. Specifically, physicians were invited, by mail, to complete a questionnaire regarding their knowledge of key safety messages, as outlined in the aflibercept educational materials. The mailing included a study invitation letter, a hard-copy questionnaire, and a prepaid/preaddressed envelope for returning the completed questionnaire. Physicians could complete and return the hard-copy questionnaire by mail or log onto a study website and complete the questionnaire online. Follow-up invitations/reminders were sent via e-mail and/or made by phone to maximize response. Compensation to physicians was based on Canadian fair market value for health-care provider services. Recruitment and data collection occurred from 18 February 2016 to 31 March 2016.

2.2 Questionnaire

The questionnaire contained questions to measure physicians’ knowledge and understanding of the key information in the aflibercept educational materials (i.e. the vial preparation instruction card, the intravitreal injection procedure video, and the product monograph). Specifically, the questionnaire included items in the following content areas: aseptic techniques to minimize risk of infection, including periocular and ocular disinfection; use of povidone iodine or equivalent; techniques for the intravitreal injection; and key signs and symptoms of intravitreal injection-related side effects. The questionnaire also included items to characterize the physicians and their practices, to investigate physicians’ receipt and review of the educational materials, and to elicit physicians’ ratings of the usefulness of the educational materials. The supplementary material presents the full survey instrument.

2.3 Statistical Methods

All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 statistical software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Data analyses were descriptive and focused primarily on summarizing the questionnaire responses. The analysis population consisted of respondents who were eligible for the study, provided informed consent, and completed at least one knowledge question. Response distribution percentages for a question were based on the total number of respondents given an opportunity to answer the question, which excluded those who were asked to skip due to an answer given in a prior question (skip pattern). Skip patterns were enforced post hoc; that is, data for physicians who provided responses even when they should have skipped a question were excluded from the analyses. In the event that respondents did not follow instructions when responding (e.g. selected multiple responses on single-response items on paper questionnaires), efforts were made to summarize the deviation. Exact 95% confidence intervals were generated around the percentage of participants who answered each knowledge question correctly. In addition to the overall results, the question about storage and preparation of aflibercept was stratified by responses to the question about responsibility for the preparation of aflibercept (see the supplementary material). Responses to the knowledge questions were also stratified by whether physicians reported having received and reviewed the Eylea Vial Preparation Instruction Card.

3 Results

3.1 Physician Characteristics

Of the 308 physicians invited to participate in the survey, 95 completed the questionnaire and were included in the analysis population (Fig. 1), making the overall response rate 31%. Physicians’ focus within ophthalmology varied, with a majority specializing in treatment of the retina (71%) and/or general ophthalmology (59%) (Table 1). Most physicians (79%) had been practicing for more than 5 years, had prescribed aflibercept in the past 6 months (87%), and had administered an aflibercept injection in the past 6 months (96%). Physicians reported prescribing and/or administering aflibercept for wAMD (94%), visual impairment due to macular edema secondary to CRVO (81%), and visual impairment due to DME (93%). Most physicians had primary responsibility for the preparation of an aflibercept injection (63%).

3.2 Physician Knowledge

3.2.1 Storage and Preparation

Physicians were asked six true/false statements related to the storage and preparation of aflibercept (Fig. 2). Eighty-seven percent of physicians correctly responded that aflibercept must be stored in the refrigerator; 92% correctly responded that a 30-gauge × ½ in. injection needle should be used; and 98% correctly responded that adequate anesthesia and asepsis must be provided for the patient. In addition, 83% correctly responded “false” to the statement that aflibercept “is a suspension, which contains particulates and is cloudy”, and 97% correctly responded “false” to the statement that the vial of aflibercept “is reusable between patients and can be used for multiple injections”. Finally, 54% of physicians correctly responded “false” to the inaccurate statement “prior to usage, the vial may be kept at room temperature for up to 48 hours”, and 27% responded “I don’t know” (the correct response is that the vial may be kept at room temperature up to 24 h).

3.2.2 Dosing

Physicians were asked several questions about aflibercept dosing. Most physicians (91%) correctly reported that 50 µL (2 mg) is the recommended dose (Table 2). Likewise, most physicians (91%) correctly reported that the vial contains more than the recommended dose of aflibercept, and that excess volume should be expelled before injecting. Almost all physicians (96%) correctly reported that, after removing all of the drug from the vial with a syringe, the plunger should be depressed until the tip aligns with the line that marks 0.05 mL on the syringe.

With regard to dosing recommendations for the three indications, physician knowledge was highest (95%) for a single item related to the wAMD dosing recommendation, “treatment is initiated with one injection per month for three consecutive doses, followed by one injection every 2 months” (Fig. 3). Physicians were also asked four items related to dosing recommendations for CRVO; correct responses ranged from 75 (“treatment is administered monthly”) to 89% (“prescribers are advised to periodically assess the need for continued therapy”) (Fig. 4). Finally, for the two items related to DME dosing recommendations, 83% of physicians correctly reported that aflibercept treatment “is initiated with one injection per month for the first five consecutive doses”, and 84% correctly responded “false” to the statement that after the first 5 months, aflibercept treatment “is followed by one injection every 3 months” (Fig. 5).

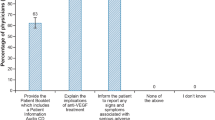

3.2.3 Safe Use

Most physicians (89%) selected all three of the correct responses to a question about contraindications for aflibercept. Correct responses to the individual items ranged from 91% for “patients with active intraocular inflammation” to 100% for “patients with a known hypersensitivity to aflibercept” (Fig. 6). Forty-nine percent of physicians correctly indicated that women of childbearing potential must use effective contraception during treatment and for at least 3 months after the last aflibercept injection, and 60% correctly indicated that aflibercept should not be used in pregnancy unless clearly indicated by medical need and the potential benefit outweighs the potential risk to the fetus (Fig. 7).

3.2.4 Injection Procedure

Physicians were asked a series of five questions about proper injection procedures (Figs. 8, 9). All but one physician (99%) correctly responded that topical anesthesia should be used prior to injection. Likewise, most physicians (95%) correctly responded that a disinfectant should be applied to the periocular skin, eyelid, and ocular surface. Physicians were also asked to identify steps that should be taken prior to marking the scleral injection site. Almost all physicians (98%) correctly selected “insert a sterile lid speculum”; however, only one-quarter (24%) correctly selected “cover the eye with a sterile drape”. Most physicians (91%) correctly reported that, in preparation for the injection, the eye should be marked at a distance 3.5–4.0 mm posterior to the limbus. Nearly all physicians (99%) correctly reported that the injection needle should be inserted into the vitreous cavity, avoiding the horizontal meridian and aiming toward the center of the globe.

3.2.5 Possible Side Effects

Physicians were asked two questions about procedures following injection. Most physicians (95%) correctly agreed to the statement that an increase in intraocular pressure has been seen within 60 minutes after an injection with aflibercept. Most physicians also correctly responded that patients should report any symptoms suggestive of intraocular inflammation (93%) and endophthalmitis (98%).

When given a list of potential related side effect symptoms of aflibercept injection, each potential symptom was correctly selected by at least 89% of physicians: endophthalmitis (99%), transient increased intraocular pressure (100%), cataract (traumatic, nuclear, subcapsular, cortical) or lenticular opacities (89%), and retinal tear or retinal detachment (98%) (Fig. 10). However, fewer physicians correctly identified fever (77%) and headache (36%) as incorrect responses.

When asked what to do in relation to the potential of increased intraocular pressure immediately following injection, 86% of physicians correctly responded “ensure that sterile equipment is available to perform paracentesis, if necessary”, and 93% correctly responded “undertake appropriate monitoring if increased intraocular pressure is suspected (e.g. check for perfusion of the optic nerve head or tonometry)”.

3.3 Receipt and Use of Educational Materials

Physicians were asked whether they received and/or reviewed the aflibercept educational materials (Table 3). Most physicians (82%) reported that they received the vial preparation instruction card. Of those who received the card, 67% reported that they reviewed it. Nearly half of physicians (46%) reported that they received the intravitreal injection procedure video. Of those who received the video, 26% reported that they reviewed it. Nearly all physicians (98%) reported that they received the product monograph. Of those who received the product monograph, 76% reported that they reviewed it.

For the 11 physicians who did not review any of the educational materials, a follow-up question was asked to determine why. Five physicians (45%) reported that they “already knew the information”. Two physicians (18%) selected each response “did not receive the materials” and “used another source”. The categories “materials were too long”, “Other”, and “I don’t know, or I don’t remember” were each checked once. Two physicians did not answer the question.

Finally, physicians were asked to rate how helpful the educational materials were in treating and educating patients (1 = not at all helpful to 4 = extremely helpful). Most physicians rated the vial preparation instruction card a 3 (40%) or 4 (37%), the intravitreal injection procedure video a 3 (47%) or 4 (40%), and the product monograph a 3 (46%) or 4 (32%).

Physicians’ responses to the knowledge questions were stratified by whether they had received and reviewed the Eylea Vial Preparation Instruction Card. These analyses revealed knowledge to be similar for most questions, regardless of physicians’ receipt of the educational material (data not shown). Knowledge was slightly higher among physicians who reported having received and reviewed the card versus those who did not for approximately half of the knowledge questions and was notably higher for another handful of items related to storage and preparation, dosing, and use in pregnancy. Given the small sample size, variations in knowledge among these subgroups should be interpreted with caution.

4 Discussion

Physicians’ knowledge of the key safety information outlined in the aflibercept educational materials was high. Most physicians (83–98%) correctly answered the storage and preparation questions, although fewer physicians (54%) correctly identified the question about storage duration at room temperature as inaccurate. Knowledge of dosing and dose preparation was high overall (91–96%) but varied somewhat by indication, being highest for wAMD (95%) and somewhat lower for CRVO (75–89%). Most physicians (89% overall) knew the contraindications for aflibercept. While 60% of physicians correctly reported that aflibercept should not be used in pregnancy unless clearly indicated by medical need and unless the benefit outweighed risks, an additional 21% more conservatively indicated that aflibercept should never be used in pregnancy. That physician knowledge of the use of aflibercept in pregnancy was lower than for other aspects of safe use may be an effect of the demographics of patients affected by wAMD, who tend to be older than childbearing age. These findings are largely consistent with those from a study of European physicians’ knowledge of safe use for aflibercept, in which 59% of physicians knew that aflibercept should not be used in pregnancy unless clearly indicated by medical need in which benefits outweigh risks and 27% responded more conservatively that aflibercept should never be used in pregnancy [20].

Knowledge was generally high on questions about injection procedures (91–99% on individual items), but fewer physicians (24%) correctly reported that the eye should be covered with a sterile drape before marking the scleral injection site. This step is recommended as part of aseptic procedures but is not common medical practice among ophthalmologists in Canada [13]. Knowledge was also high about possible side effects (89–100%) and actions to take in relation to the potential increased intraocular pressure (86–93%).

Almost all physicians (98%) reported receipt of the product monograph, and most (82%) reported receipt of the vial instruction card. A lower proportion (46%) reported receipt of the intravitreal injection procedure video, possibly because the video was distributed on a USB drive together with the card. The relatively low level of receipt reported for the video may reflect poor recall or that physicians may not have considered that the video was on the provided USB drive when answering the question surrounding the receipt of the video. In addition, because the video provides information on the intravitreal injection procedure, it is possible that ophthalmologists were uninterested in reviewing the video, given their experience with the injection procedure itself. Nevertheless, despite the reported level of receipt of the video being low, the majority of prescribers were aware of the key points of information. This finding, which points to the importance of not burdening physicians with too much information or additional activity, may be informative for future studies.

In comparison with our findings, a recent multinational survey found that the rate of reported receipt of educational materials among 800 European physicians ranged from 16% to 69% across the participating countries [14]. Other post-authorization safety studies have identified rates of reported receipt of educational materials ranging from 37 to 75% [15,16,17].

Key strengths of this study include the comprehensiveness of the prescriber list used for recruitment and the diversity of the sample in terms of specialty focus, years in practice, and prescribing practice. In addition, a mixed-mode approach was used for recruitment and collecting data, in that respondents were contacted by mail and phone and could complete a hard-copy or an electronic questionnaire, depending on their preference; this approach provided physicians with maximum flexibility in participating. A particular strength is the relatively high response rate (31%), which is higher than response rates in other studies of physician knowledge [15,16,17,18,19,20]. In addition, the original target of 50 respondents was exceeded by almost 100%. The survey was also conducted after physicians had received the educational materials and had an opportunity to use them in clinical practice.

Nevertheless, some limitations inherent to voluntary survey studies must be noted. Study participants may not necessarily represent all relevant prescribers of aflibercept in Canada. Respondents who completed the questionnaire may have differed from nonrespondents in characteristics measured in the questionnaire. The direction and magnitude of potential respondent bias is unknown, and a comparison of participants and nonparticipants was not possible. Finally, although the response rate was high and the number of respondents exceeded the target sample size, the sample was nevertheless small, limiting the generalizability of the results.

5 Conclusion

Nearly all physicians (98%) reported having received the product monograph, and most (82%) reported having received the vial preparation instruction card; nearly half (46%) reported having received the intravitreal injection procedure video. Physicians’ knowledge of the most important safety and administration topics (e.g. dosing, injection procedures, and contraindications) was high. Knowledge varied for topics encountered less frequently (e.g. use in women of childbearing potential) and for recommendations that are not part of current standard medical practice in Canada (e.g. use of a sterile drape).

References

Campa C, Harding SP. Anti-VEGF compounds in the treatment of neovascular age related macular degeneration. Curr Drug Targets. 2011;12:173–81.

Kooragayala LM. Central retinal vein occlusion. 2014. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1223746-overview. Accessed 6 Jun 2016.

Folk J, Stone E. Ranibizumab therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. New Engl J Med. 2010;363:1648–55.

Jager R, Mieler W, Miller J. Age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2606–17.

Jeganathan VS, Verma N. Safety and efficacy of intravitreal anti-VEGF injections for age-related macular degeneration. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2009;20:223–5.

Vedula SS, Krzystolik MG. Antiangiogenic therapy with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor modalities for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2:CD005139.

Mitra A, Lip P-L. Review of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy in macular edema secondary to central retinal vein occlusions. 2011. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/755101. Accessed 6 Jun 2016.

Boyer DS, Hopkins J, Sorof J, Ehrlich JS. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy for diabetic macular edema. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2013;4:151–69.

Eylea Product Monograph. Bayer Inc. 19 May 2017. http://www.bayer.ca/omr/online/eylea-pm-en.pdf. Accessed 6 Jul 2017.

Csaky K, Do DV. Safety implications of vascular endothelial growth factor blockade for subjects receiving intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapies. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148:647–56.

Micieli JA, Micieli A, Smith AF. Identifying systemic safety signals following intravitreal bevacizumab: systematic review of the literature and the Canadian adverse drug reaction database. Can J Ophthalmol. 2010;45:231–8.

International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology. Guidelines for good pharmacoepidemiology practices (GPP). Revision 3. April 2015. http://www.pharmacoepi.org/resources/guidelines_08027.cfm. Accessed 7 Jun 2016.

Xing L, Dorrepaal SJ, Gale J. Survey of intravitreal injection techniques and treatment protocols among retina specialists in Canada. Can J Ophthalmol. 2014;49:261–8.

Brody RS, Liss CL, Wray H, Iovin R, Michaylira C, Muthutantri A, et al. Effectiveness of a risk-minimization activity involving physician education on metabolic monitoring of patients receiving quetiapine: results from two postauthorization safety studies. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;31:34–41.

Davis KH, Asiimwe A, Zografos LJ, McSorley D, Andrews EB. Evaluation of risk-minimization activities for cyproterone acetate 2 mg/ethinylestradiol 35 µg: a cross-sectional physician survey. Pharm Med. 2017;31:339–51.

Madison T, Huang K, Huot-Marchand P, Wilner KD, Mo J. Effectiveness of the crizotinib therapeutic management guide in communicating risks, and recommended actions to minimize risks, among physicians prescribing crizotinib in Europe. Pharm Med. 2018;32:343–52.

Landsberg W, Al-Dakkak I, Coppin-Renz A, Geis U, Peters-Strickland T, van Heumen E, et al. Effectiveness evaluation of additional risk minimization measures for adolescent use of aripiprazole in the European Union: results from a post-authorization safety study. Drug Saf. 2018;41:797–806.

Wiebe ER, Kaczorowski J, MacKay J. Why are response rates in clinician surveys declining? Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:e225–8.

Flanigan TS, McFarlane E, Cook S, editors. Conducting survey research among physicians and other medical professionals—a review of current literature. Oakbrook Terrace: American Association for Public Opinion Research; 2008.

Zografos LJ, Andrews E, Wolin DL, et al. Physician and patient knowledge of safety and safe use information for aflibercept in Europe: evaluation of risk-minimization measures. Pharm Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40290-019-00279-y.

Acknowledgements

Kate Lothman of RTI Health Solutions provided medical writing assistance by drafting the manuscript under the authors' guidance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was performed under a research contract between RTI Health Solutions and Bayer AG and was funded by Bayer AG. The contract between RTI Health Solutions and the sponsor includes independent publication rights. Medical writing assistance for this manuscript was funded by Bayer AG. Open access fees were paid by Bayer AG.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

Laurie Zografos, Dan Wolin, Brian Calingaert, Eric Davenport, Kelly A. Hollis and Elizabeth Andrews are salaried employees of RTI Health Solutions, which received funding from Bayer AG to conduct this study. The contract between RTI Health Solutions and the sponsor includes independent publication rights. RTI International conducts work for government, public, and private organizations, including pharmaceutical companies. Zdravko P. Vassilev is an employee of Bayer U.S. Paul Petraro was an employee of Bayer U.S. at the time this research was conducted. Vito S. Racanelli and Nada Djokanovic are employees of Bayer Inc., Canada.

Research involving human participants

All procedures performed this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the applicable institutional review board and ethics committees and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zografos, L.J., Andrews, E., Wolin, D.L. et al. Evaluation of Physician Knowledge of the Key Safety Information for Aflibercept in Canada: Evaluation of Risk-Minimization Measures. Pharm Med 33, 235–246 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40290-019-00278-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40290-019-00278-z