Abstract

Background

Medication discrepancies are common, potentially harmful and may result from poor medication information across medical records. Our aim was to describe current medication discrepancy rates, types and severity in hospital, primary and specialized outpatient care in Sweden, as well as comparing these with previous measurements.

Methods

Participants visiting health care in Skåne in November 2020 were randomly selected to include 100 adult patients each in public and private primary health care centers, hospitals and outpatient care. Within 2 weeks after a health care visit or hospital admission, a pharmacist medication reconciliation was performed to identify any discrepancies. Two general practitioners assessed their potential to cause harm. Descriptive and comparative statistics were used.

Results

In total, 405 patients (mean age 61.6 years, median 6.5 medications) were included in the analysis. The majority (72%) of the included patients had ≥1 medication list discrepancy. Total number of discrepancies was 1038 (average 2.6 per patient), with a significantly higher discrepancy rate (4.5) noted in specialized outpatient care (p < 0.001). Overall, unintentional addition (44%) or omission (39%) of drug were most frequent. Out of all discrepancies, 20.7% were rated to have moderate (18.2%) or high (2.5%) potential risk of harm. Cardiovascular, nervous system and antidiabetic medications were more often involved in potentially harmful discrepancies. When compared with previous measurements, the proportion of accurate medication lists significantly improved in primary care compared to 2018 (34% vs 20%, p = 0.0011), as well as a decrease in overall discrepancy rate (p = 0.0029).

Conclusion

Medication discrepancies were in general abundant despite a recent health care visit, both in hospital care and primary care, with the highest number in specialized outpatient care. A considerable share was classified as potentially harmful thus implying a major threat to medication safety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The average number of discrepancies in the electronic medical record medication lists was 2.6, and 72% of the lists contained at least one discrepancy, although the patient had a recent health care visit. |

Although the proportion of accurate medication lists was significantly improved in primary care compared to previous measurements, the results suggest that the extent of medication discrepancies still pose a major threat to medication safety in both outpatient and inpatient care. |

Out of all discrepancies, 2.5% were judged as very severe and among these, agents that affect the angiotensin system were the most frequent substances. |

Introduction

Medication errors have the potential to cause drug-related problems and consequently patient harm [1]. The term medication error has been defined as addition, omission or changed dosage of drug without documentation, while medication discrepancy is a broader concept commonly also including changes in mode or frequency of administration [2, 3]. Discrepancies between medication lists in electronic medical records (EMRs) and the treatment used by the patient entail a poor decision basis for the prescriber and a risk for incorrect or incomplete treatment. Furthermore, it may be costly to society due to increased health care costs associated with drug-related problems [4].

A great share of drug-related problems is preventable, thus reducing health care costs and patient suffering [5, 6]. A challenging aspect of improving patient safety includes the transfer of correct medication information throughout the health care system [7]. Medication reconciliations are highlighted by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SALAR) in order to prevent medication errors in health care transitions [8]. The method implies that “both delivering and receiving prescriber in each transition should check, in dialogue with the patient, that the medication list is complete, correct and reasonable”. Another means to reduce medication errors and health care consumption is the discharge summary with medication report [9,10,11]. Adequate follow-up in primary care after hospitalization requires correct information [12]. However, both Swedish and international studies have found high rates of discrepancies even in the medication lists of the discharge summary [13, 14].

Medication discrepancies are common in EMRs, both in primary health care and inpatient care [2, 15,16,17]. In a Swedish study in primary health care, the most common medication group among all discrepancies was analgesics and among dose discrepancies it was cardiovascular drugs [15]. These medication groups were also frequently involved in adverse drug events following hospital discharge [17]. Although discrepancies are potentially harmful, they may vary in severity from mild to very severe. A study by Cornish et al defined a three-point scale to facilitate the assessment of the severity of discrepancies [2].

Many medication discrepancies result from the fragmented nature of the health care system combined with poor communication between health care providers [7]. In Skåne, a region in Southern Sweden with approximately 1.3 million inhabitants, two different EMR systems are used for inpatient and specialized outpatient care and primary health care respectively. When the patient´s medication list is updated in one of the EMRs, no corresponding correction takes place in the other thus implying a substantial risk of medication discrepancies. Work is underway to introduce a common EMR platform, which is intended to link health care throughout Skåne with common working methods, including a common medication list [20]. In order to evaluate whether the number of medication errors decreases when introducing a common system, it is important to describe an initial position.

The Group Council for Patient Safety in Skåne conducted point prevalence measurements of current medication lists in 2017 and 2018, respectively [18, 19]. Approximately 300 patients were included in each measurement. Discrepancies were identified in three out of four patients and the most common discrepancy was omission of drug. The median number of discrepancies per patient was two in both measurements, while the average number of discrepancies per patient was 3.4 in 2017 and 3.1 in 2018. Since these measurements, continuously but especially after 2018, regional actions such as the production of pocket leaflets, training for prescribers and public information have been taken to improve the situation.

The aim of this study was to describe the extent, distribution and severity of medication discrepancies in the EMRs in hospital care, primary care, and specialized outpatient care in the Skåne area as well as if regional actions had led to any changes.

Material and methods

Population/setting

In Skåne, there are nine hospitals and 167 primary health care centers (PHCCs), both public and private. Since 2012, clinical pharmacists perform multi-professional medication reviews together with registered nurses and physicians, including medication reconciliations, according to national regulations [21].

Data collection

Eligible patients were recruited from primary and secondary care in different parts of Skåne and were randomly selected by the Department of Data Analytics and Health Care Register Region Skåne. Inclusion criteria were age ≥ 18 years, a PHCC or specialized outpatient care visit in the first week of November 2020 or hospitalized during the third week of November 2020 and availability for a telephone interview (either the patient or the person managing the patient’s medication list in cases of cognitive impairment or other chronic disability). To ensure the inclusion of at least 400 patients (100 respectively from each group, i.e. public PHCCs, private PHCCs, outpatient care and hospital), five times as many patients were randomly selected (hospitalized patients were randomly selected on Monday and Wednesday, 2–5 days after hospital admittance). For patients who had visited a PHCC or specialized outpatient care, a letter with information about the study was sent, while hospitalized patients received the information letter during the hospital stay. Patients admitted to intensive care units, psychiatric care or forensic psychiatry were among those excluded.

Patients at PHCCs and hospital outpatient care were contacted by telephone two weeks after the doctor visit, and patients in hospital clinics were contacted 2–5 days after hospital admission. Calls were placed at different times during the day and up to three attempts were made to contact each patient. Verbal informed consent was obtained prior to the interviews. During the telephone interview, the pharmacist performed a reconciliation of the medication list. The patient’s medication list in the EMR was compared to prescribed and used medications as reported by the patient at the interview. Selected patients were excluded from the analysis if they did not answer the telephone interview or did not give consent to be part of the study, or if they were already discharged at the time of the interview.

Before the interviews started, all pharmacists involved attended a meeting where the instructions were discussed and clarified. The questions used in the assessment were developed and used repeatedly in previous regional measurements. Face-validity of the questions in the interview-guide was performed during this meeting. A protocol for data collection was presented (Appendix A), in addition to a detailed explanation of the medical reconciliation form (Appendix B) and how to categorize discrepancies.

A discrepancy was found and noted if the medication list in the EMR did not correspond to the medications the patient reported at the time of the doctor visit. Discrepancies included omission or addition of medication, change in dose (higher or lower), or in frequency. Temporary antibiotic regimens that were not removed from the medication list were considered as technical errors and not classified as discrepancies. The result of the reconciliation was documented in the EMR, and the doctor was contacted, if needed. During the interviews (the last two weeks of November 2020) questions regarding interviews and classifications of discrepancies could be asked to the steering committee.

The checklist included background information about the patients as follows: age, sex, clinic, number and name of drugs (continuous and as needed), medication changes during the visit or hospital care, drug dispensing, other reconciliation during the hospital admission.

Discrepancy severity

The discrepancies were assessed for their potential to cause harm according to Cornish et al. [2] by two general practitioners (GPs) with extensive clinical training and knowledge about drug safety in the elderly. First, the GPs together reviewed a limited sample of medication lists, to adjust the assessment method. In a second step, the GPs assessed the medication lists independently. Finally, the GPs discussed the discrepancies until consensus was reached.

Class 1 discrepancies were those considered as unlikely to cause patient discomfort or clinical deterioration. An example of a class 1 discrepancy was if a patient was no longer prescribed and using a bisphosphonate, despite lack of medication removal in the EMR. Class 2 were those discrepancies with the potential to cause moderate discomfort or clinical deterioration. For example, a class 2 discrepancy was omission of antidepressant medication or wrong dose of betablocker. Class 3 discrepancies had the potential to result in severe discomfort or clinical deterioration, for example, omission of diabetes medication (e.g., GLP1-agonists, insulin, certain oral antidiabetics), or omission/addition of blood pressure medications particularly in elderly patients with polypharmacy.

Ethics

This study has been approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority, ref 2020-03593.

All patients were provided with written information about the study, including information about the possibility to withdraw without giving a reason/explaining why, according to requirements in the Swedish ethical approval process. To keep anonymity, patients were given a number and the initials of the pharmacist doing the medication reconciliation.

Comparison with earlier measurement

Results were compared with the corresponding measurement including 300 patients (100 patients from hospital care, public primary healthcare centers and specialized outpatient care respectively) performed in 2018 [19].

Statistical analysis

Number, percentage, and classification of discrepancies were assessed with descriptive statistics. The comparison was performed between two independent samples (the sample in our study and the earlier measurement). As the variables were not normally distributed (when reviewing the distribution graphically), the Mann Whitney’s test was used for the comparison between numbers of discrepancies. Comparison of proportion of correct medication lists was performed using chi2-test. Association between number of drugs and discrepancies was assessed with scatter plot. Inter-rater reliability was tested using Cohen´s kappa coefficient where a value ≥ 0.81 is considered as very good [22].

A power calculation based on the results from the 2018 measurement was performed prior to the data collection. It showed that the estimated number of medication reconciliations (100 × 4) was enough for the planned comparative statistics, using average number of discrepancies per list (effect size 0.25) [23] or proportion of correct medication lists, respectively.

Excel 2010 and Excel Office 365, including Sigma Zone SPC XL add on, was used for the statistical analysis.

Results

In total, pharmacists interviewed 405 participants: 101 patients in university or county hospital care, 205 patients in primary care (103 from public PHCCs and 102 patients from private PHCCs) and 99 patients in specialized outpatient care. Patients were recruited from all over Skåne County, with predominance for the bigger cities with university hospitals. Half the included patients met a GP, and the rest came from a variety of specialties, such as surgery, internal medicine, orthopedics and psychiatry. Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1.

A total of 1038 discrepancies were identified. Out of all 405 patients, 290 (72%) had at least one discrepancy in their medication list and 115 (28%) had no discrepancies in their medication list. Eighty-four patients (21%) had one discrepancy and 59 patients (15%) had two, while 17 patients (4%) had 10 or more discrepancies in their medication list. The average number of medication discrepancies was 2.6 per patient while the median was 2 discrepancies per patient. Significantly more discrepancies were noted in the medication lists from specialized outpatient care (4.5) as compared to lists from primary (1.9) or hospital care (1.9) (p < 0.001). The association between number of medications and number of discrepancies was very weak (R2 = 0.2295).

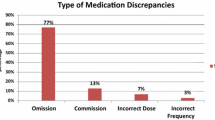

Overall, the most common discrepancy was “unintentional addition of drug” (44%), “omission of drug” (39%) and “another dose regimen” (8%). This order was regardless of whether over the counter (OTC) drugs were included or not (Fig. 1).

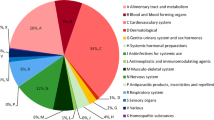

The most common drugs involved in the discrepancies were paracetamol/acetaminophen (61/1038, 5.9% of all), omeprazole (26/1038, 2.5%), diclofenac and furosemide (22/1038, 2.1%) each, and oxazepam and ibuprofen (20/1038, 1.9%). The most frequent class of medications noted, according to the second level of the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification system, were analgesics (10%), followed by psycholeptics (8.8%), anti-inflammatory and antirheumatic drugs (5.3% each) (Table 2).

Discrepancy severity

The majority of all discrepancies (79.3%, 823/1038) were rated as class 1, while 18.2% (189/1038) were rated as class 2 and 2.5% (26/1038) as class 3. Among the class 3 discrepancies, the most common type of discrepancy was omission and addition of drugs with 12 cases each; the remaining two cases were use of lower dose than prescribed. Regarding discrepancies assessed as potentially harmful (class 2 or 3), cardiovascular, nervous system and antidiabetic drugs were more commonly involved as compared to all discrepancies (Table 2).

The inter-rater reliability was strong with Cohen’s kappa equal to 0.89 (Table 3). The raters initially disagreed in 4% of the assessments (39/1038). The majority of disagreements (38/39, 97%) differed one grade between the raters and one differed two grades. When a disparity between the raters was identified and adjusted, after consensus, the higher grading was agreed upon in 23% (9 out of 39) and the lower grading in 74% (29 out of 39) of cases. In the single disagreement differing two grades (1 and 3 respectively), the grading was adjusted to two. When the raters disagreed, rater one had their original assessment corrected in 41% (16/39) of the cases while rater two had their assessment corrected in 56% (22/39) of the cases.

Some discrepancies were considered technical errors. These were mainly antibiotics but also other prescriptions that were obviously discontinued. In all, 108 technical errors were identified, i.e. drugs still on the medication lists even though the drug was intended for a limited treatment. The most frequent class of medication causing technical errors were antibacterials for systemic use (J01) with 25 errors, corticosteroids for dermatological use (D07) with nine, corticosteroids for systemic use (H02), analgesics (N02) and ophthalmologicals (S01) all with seven errors each.

Comparison with earlier measurement

In comparison with the 2018 measurement [19] that was performed in 306 patients, the mean number of discrepancies was lower (2.6 as compared to 3.1). Comparison analysis with Mann Whitney test showed a significant difference (p = 0.002). The proportion of patients without discrepancies was numerically higher with the latest assessment compared with the 2018 assessment (28% vs 25%). Most of the improvement occurred in primary care where the percentage of lists with no discrepancies increased from 20% to 34% (p = 0.011). The mean number of discrepancies decreased from 2.8 to 1.9 (p = 0.002). No significant changes were seen for inpatient or specialized outpatient care.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study conducted in Skåne in Sweden showed that the average number of discrepancies in the medication lists of the EMRs was 2.6 and 72% of the lists contained at least one discrepancy, although the patient had a recent health care visit. Despite a decrease compared to previous measurements conducted in 2018 [19], the results showed that the extent of medication discrepancies still pose a major threat to medication safety in both primary care and hospital care, as a substantial proportion were classified as potentially harmful.

High frequencies of discrepancies were also seen in previous research. In primary health care, the proportion of patients who had at least one discrepancy in their medication list was even higher in previous studies, both in Sweden and internationally [15, 16, 24]. A study, which was conducted in the same area of Sweden, found an average number of discrepancies of 3.8 two weeks after a follow-up visit to a general practitioner [15]. Regarding inpatients, an international systematic review from 2015 found that a patient had, on average, 1.2–5.3 discrepancies at hospital discharge [25], also noted in Sweden [13] and Norway [26]. Furthermore, in both a Canadian and a Spanish study, at the time of admission more than half of the patients had at least one discrepancy, of which omission of medication was the most common type [2, 27]. The risk of error at admission was higher with more pre-admission drugs [27], while in the current study the association between number of medications and number of discrepancies was very weak.

In the current study, the number of discrepancies was not associated with number of medications, but rather with type of care provider. The average number of discrepancies in specialized outpatient care was 4.5, compared to 2.6 for the total sample. It might therefore be fruitful to concentrate forthcoming interventions here. In a fragmented health care system, care coordination challenges including medication list discrepancies are well-known [7, 28]. It is possible that the common medication list may not be highly prioritized in a specialized care point effort as reconciling the medication list is a time consuming and demanding task. However, if the resulting discrepancies are of severe nature, patient harm may occur.

In previous studies, omission of drug was often the most common type of discrepancy upon hospital admission [2, 25, 27], while addition of drug was commonly seen for outpatients [16]. The current study showed that unintentional addition of drug was the most common discrepancy. This is in-line with previous research [16], and partly due to three quarters of the study population being outpatients. A possible explanation is automatic pasting of the previous hospital medication list during the actual hospital admission, despite more recent medication changes, as withdrawal of drug, in outpatient care.

A systematic review, which aimed to identify and evaluate the available evidence on medication errors and medication-related harm following hospital discharge [17], identified seven studies which reported adverse drug event rates with a median of 19%. Drug classes most implicated with adverse drug events were antibiotics, antidiabetics, analgesics and cardiovascular drugs. In the current study, the most common substances among the most serious discrepancies (rated as 3) were agents that affect the angiotensin system. This is in line with previous findings from Sweden showing that cardiovascular drugs were among the most common among drugs causing hospitalization [29]. Dose-related adverse events dominated and one third of the patients had a kidney function impairment [29]. One of the most important aspects of drug treatment with ACE-inhibitors is assessment of a patient’s kidney function. One example from the reconciliations in this study was a 72-year-old woman who was prescribed Ramipril 5 mg twice a day but did not comply with the treatment. Instead, she used Candesartan 16 mg, not on the list, and also Diclofenac 50 mg three times a day. In case of acute renal failure caused by diclofenac, concomitant treatment with ramipril and candesartan by mistake might induce severe hyperkalemia.

Although less severe, the technical errors identified in the assessments can still cause health deterioration, for example if discontinued medication is still present on the medication list and interferes with the actual medication. The built-in help systems for assessing interactions become more difficult to use. A need for further education among prescribers regarding nurturing the medication list including the removal of outdated prescriptions has previously been observed [30].

Compared to 2018, the average number of discrepancies has decreased significantly. Regional actions, such as the production of pocket leaflets, training for prescribers and public information, might have contributed to this decrease. Despite an improvement, it is of the highest importance that further work continues regarding this safety issue, since more than 7 out of 10 patients still have discrepancies. The Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SALAR) encourages incorporating medication reconciliations into clinical routines [8]. A possible explanation for medication errors is use of different EMRs in primary care and hospital care, which can lead to a fragmented picture of a patient’s medication list. During recent years, local authorities have made efforts towards implementation of a common EMR for all health care givers, which might improve communication between primary care and hospital care. Furthermore, in Sweden, a national drug list is underway which will enable each prescriber to see what others have prescribed as well as discontinued.

A Cochrane review from 2017 concluded that interventions in primary care for reducing preventable medication errors probably make little or no difference to the number of hospitalizations, emergency department visits, or to mortality [31]. Thus, it is even more important to work on the basis of evidence. Medication reconciliation and discharge summary with medication reports have been shown to reduce medication errors and health care consumption [10, 11]. Even though discharge summaries were considered clear and reliable by the GPs in a previous Swedish study, only one third of medication lists were updated in primary care EMRs two weeks after discharge for patients with drug changes during hospitalization [32]. The discharge summary must be adequately transferred and used to fully exploit its potentially beneficial effect on improved accuracy of medication lists and, consequently, patient safety. Therefore, one must then take into account what the clinicians consider important. According to a study in primary care by Tudor et al, the highest ranked measures to reduce medication errors included the use of a standardized discharge summary template and the reduction of unnecessary prescribing through quality assurance approaches. Better communication between the healthcare provider and the patient as well as patient education on how to use their medication were called for. According to clinicians, medication errors can be largely prevented with feasible interventions [33]. Doormaal et al showed that a minority of prescribing and transcribing errors lead to adverse drug events (ADEs), while in particular therapeutic errors were the cause of preventable ADEs. Therapeutic errors include interactions, contra-indications, incorrect monotherapy, duplicated therapy, and errors on therapeutic drug monitoring. Interventions should therefore primarily focus on this type of medication error [34].

In this study, 28% of the medication lists were free of discrepancies; a slight increase compared to previous findings. Yet, it must be taken into account that almost one fifth of the discrepancies were assessed with a severity of 2–3 (i.e., potential to cause moderate to severe discomfort or clinical deterioration). In a Norwegian study performed in five internal medicine wards, 80% of the medication lists contained discrepancies and among these, the majority were judged to have the potential to harm the patient in a longer-term perspective [26]. A Canadian study found that four out of ten discrepancies had the potential to cause moderate to severe discomfort or clinical deterioration [2]. In this perspective, discrepancies with potential of serious harm were less common in the current study, which might be explained by including both inpatients and outpatients. Nevertheless, in terms of the total amount of discrepancies, these can still cause significant damage.

Although morbidity and mortality of patient related to medicine discrepancy was not evaluated in the study, Shui et al found that most unintentional discrepancies were judged inconsequential, and the presence of an unintentional medication discrepancy was not associated with 90-day readmission or death or ED visits [35]. This can imply that the discrepancies judged as one in the current study (three out of four) will not likely lead to harm or affect health care consumption. However, several minor discrepancies simultaneously might lead to a more severe outcome, although not studied in this project.

Strengths and limitations

This study was based on material that includes 400 patients, which provides a basis for good reliability. The inter-rater reliability was excellent when it came to the assessment of discrepancy severity. The method with clinical pharmacists identifying the discrepancies and GPs grading the severity is also a strength of the study, by using a multi-professional approach in the assessment. The study population was drawn from primary and secondary health care sectors across Skåne Country, potentially increasing the generalizability of our findings in a Swedish population. The study was integrated into a regional quality improvement work, which makes it clinically relevant and useful for ongoing interventions.

However, the study also comes with some limitations. It was not designed as an intervention study even though improvement work with increased focus on medication lists’ accuracy performed broadly in both primary and secondary care between the measurements 2018 and 2020 could be seen as an intervention. Power calculation was performed before the current measurement, however. The proportion of medication lists from included types of care providers differed between 2018 and 2020. Half of the reconciliations were performed in primary care at the latter measurement, compared with a third in 2018. However, there was no significant difference between private and public primary care regarding discrepancies.

The pharmacists performed the assessments after patient visits at open patient departments or hospital clinics. As the health care is fragmented, only some diagnoses might have been registered in the electronic medical record, and therefore not give a comprehensive picture on patient’s comorbidities. Therefore, we decided not to collect diagnose data. This is a limitation of our study when it comes to the assessment of severity of discrepancies. Another limitation of the study is the sex distribution between primary care and hospital care patients, with a higher percentage of women who accepted to participate in the study in the primary care settings. As we did not collect diagnose data, we cannot draw any conclusion if the difference in number of medications between the settings is correlated to differences in morbidity between men and women.

Some subjectivity may have occurred in the discrepancy assessments even if the pharmacists had guidelines to lean against. This was counteracted with an initial meeting and the opportunity to ask questions to the steering group during the time the reconciliations were made. As for the GP assessments of possible discrepancy harm, information on patients was limited to age, concurrent medications and point of care, thus lacking, for example, data on renal function. Providing specific time limits regarding possible discrepancy harm would perhaps have altered the assessments. Our study was not designed to measure outcomes in terms of morbidity or mortality. The assessments were merely estimates as the clinical outcomes were in fact not explored.

Future research

This study will provide a good basis regarding the evaluation of whether the number of medication discrepancies decreases when introducing a common EMR system. The attitude among prescribers regarding responsibility for the medication list has previously been explored in Swedish qualitative research but would be valuable to re-examine when using a common system. We also suggest that a future complementary study design should consider a longer follow up time, assessing outcomes as impact on preventability of drug-related problems, morbidity and mortality.

Conclusion

Medication discrepancies were in general abundant despite a recent health care visit, both in hospital care and primary care, with the highest number in specialized outpatient care. A considerable share was classified as potentially harmful thus implying a major threat to medication safety.

References

Aronson JK. Medication errors: definitions and classification. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67(6):599–604.

Cornish PL, Knowles SR, Marchesano R, et al. Unintended medication discrepancies at the time of hospital admission. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(4):424–9.

Almanasreh E, Moles R, Chen TF. The medication discrepancy taxonomy (MedTax): the development and validation of a classification system for medication discrepancies identified through medication reconciliation. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2020;16(2):142–8.

Walsh EK, Hansen CR, Sahm LJ, et al. Economic impact of medication error: a systematic review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(5):481–97.

Hakkarainen KM, Hedna K, Petzold M, et al. Percentage of patients with preventable adverse drug reactions and preventability of adverse drug reactions—a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(3):e33236.

Hodkinson A, Tyler N, Ashcroft DM, et al. Preventable medication harm across health care settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):313.

Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, et al. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–41.

Sveriges Kommuner och Regioner (SALAR). [Patientens övergångar]. Stockholm; 2017. https://skr.se/download/18.4829a209177db4e31aa42943/1615817137835/Patientens%20%C3%B6verg%C3%A5ngar.pdf Accessed 2022-03-01.

Midlov P, Holmdahl L, Eriksson T, et al. Medication report reduces number of medication errors when elderly patients are discharged from hospital. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30(1):92–8.

Midlov P, Deierborg E, Holmdahl L, et al. Clinical outcomes from the use of medication report when elderly patients are discharged from hospital. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30(6):840–5.

Bergkvist A, Midlov P, Hoglund P, et al. Improved quality in the hospital discharge summary reduces medication errors–LIMM: landskrona integrated medicines management. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65(10):1037–46.

Karapinar F, van den Bemt PM, Zoer J, et al. Informational needs of general practitioners regarding discharge medication: content, timing and pharmacotherapeutic advice. Pharm World Sci. 2010;32(2):172–8.

Caleres G, Modig S, Midlov P, et al. Medication discrepancies in discharge summaries and associated risk factors for elderly patients with many drugs. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2020;7(1):53–62.

Akram F, Huggan PJ, Lim V, et al. Medication discrepancies and associated risk factors identified among elderly patients discharged from a tertiary hospital in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 2015;56(7):379–84.

Safholm S, Bondesson A, Modig S. Medication errors in primary health care records; a cross-sectional study in Southern Sweden. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20(1):110.

Coletti DJ, Stephanou H, Mazzola N, et al. Patterns and predictors of medication discrepancies in primary care. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015;21(5):831–9.

Alqenae FA, Steinke D, Keers RN. Prevalence and nature of medication errors and medication-related harm following discharge from hospital to community settings: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2020;43(6):517–37.

Region Skåne. [Results from the 2017 PPM current medication lists]. 2017 https://docplayer.se/109171970-Resultat-fran-2017-ars-ppm-aktuella-lakemedelslistor.html Accessed 2022-03-01

Region Skåne. [Results from the 2018 PPM current medicationlists]. https://vardgivare.skane.se/siteassets/1.vardriktlinjer/lakemedel/lakemedelssakerhet/lakemedelsavstamning/rapport-ppm-aktuella-lakemedelslistor-2018.pdf Accessed 2022-03-01.

[Skånes Digitala Vårdsystem (SDV)] https://vardgivare.skane.se/kompetens-utveckling/projekt-och-utvecklingsarbete/sdv/: Region Skåne 2021; Accessed 2022-03-01

The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. [Senaste versionen av HSLF-FS 2017:37 Socialstyrelsens föreskrifter och allmänna råd om ordination och hantering av läkemedel i hälso- och sjukvården.] 2021. Accessed 2022-03-01.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. New York: Academic Press; 1969. p. 38.

McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2012;22(3):276–82.

Ekedahl A, Brosius H, Jonsson J, et al. Discrepancies between the electronic medical record, the prescriptions in the Swedish national prescription repository and the current medication reported by patients. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(11):1177–83.

Michaelsen MH, McCague P, Bradley CP, et al. Medication reconciliation at discharge from hospital: a systematic review of the quantitative literature. Pharmacy (Basel). 2015;3(2):53–71.

Nilsson NLM, Lao Y, Wendelbo K, et al. Medication discrepancies revealed by medication reconciliation and their potential short-term and long-term effects: a Norwegian multicentre study carried out in internal medicine wards. EJHP. 2015;22(5):298–303.

Belda-Rustarazo S, Cantero-Hinojosa J, Salmeron-Garcia A, et al. Medication reconciliation at admission and discharge: an analysis of prevalence and associated risk factors. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69(11):1268–74.

Jones CD, Vu MB, O’Donnell CM, et al. A failure to communicate: a qualitative exploration of care coordination between hospitalists and primary care providers around patient hospitalizations. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(4):417–24.

Fryckstedt J, Asker-Hagelberg C. Drug-related problems common in the emergency department of internal medicine. The cause of admission in almost every third patient according to quality follow-up. Lakartidningen. 2008;105(12–13):894–8.

Modig S, Lenander C, Viberg N, et al. Safer drug use in primary care—a pilot intervention study to identify improvement needs and make agreements for change in five Swedish primary care units. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(1):140.

Khalil H, Shahid M, Roughead L. Medication safety programs in primary care: a scoping review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2017;15(10):2512–26.

Caleres G, Bondesson A, Midlov P, et al. Elderly at risk in care transitions When discharge summaries are poorly transferred and used -a descriptive study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):770.

Tudor Car L, Papachristou N, Gallagher J, et al. Identification of priorities for improvement of medication safety in primary care: a PRIORITIZE study. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(1):160.

van Doormaal JE, van den Bemt PM, Mol PG, et al. Medication errors: the impact of prescribing and transcribing errors on preventable harm in hospitalised patients. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(1):22–7.

Shiu JR, Fradette M, Padwal RS, et al. Medication discrepancies associated with a medication reconciliation program and clinical outcomes after hospital discharge. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36(4):415–21.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the clinical pharmacists involved and the County Council in Region Skåne for providing financial and administrative support to this study, including Kristian Dahlberg for statistical advice. We wish to thank Patrick Reilly, scientific editor at Center for Primary Health Care Research, for his expertise and advice in reviewing the English language.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Open access funding provided by Lund University.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Availability of data and material

The anonymized datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The study was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. This study has been approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority, ref 2020-03593.

Consent

Verbal informed consent was obtained prior to the interviews. Patients were able to withdraw at any time by communicating an individual code to the research team.

Author contribution

The study was conceived and designed by CL and SM. Material preparation data collection were performed by CL, GC and VNM. Analysis was performed by CL, FP and LL. The first draft of the manuscript was written by SM and CL and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Modig, S., Caleres, G., Nymberg, V.M. et al. Assessment of medication discrepancies with point prevalence measurement: how accurate are the medication lists for Swedish patients?. Drugs Ther Perspect 38, 185–193 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-022-00907-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-022-00907-9