Abstract

Background

Medication errors in ambulatory care are frequent and present an increased risk for adverse drug events. Polypharmacy is particularly susceptible to prescribing errors. Estimating the potential risk of such errors may lead to measures that increase patient safety.

Objective

The aim of this study was to evaluate potential prescribing errors that were identified by pharmacotherapy experts in patients receiving polypharmacy in ambulatory care.

Methods

Medication analyses of 400 patients participating in a German health insurance project and receiving polypharmacy (defined as five or more drugs) were examined. Potential prescribing errors identified were categorized into 8 main categories and 33 sub-criteria. The reliability and severity of these errors were evaluated using the Delphi method to estimate the potential risk, and a risk score was calculated. The number of responses from attending physicians receiving the results of the medication analyses was assessed.

Results

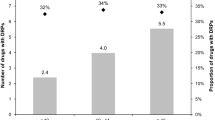

On average, patients took 13.4 ± standard deviation (SD) 3.6 drugs regularly. In total, 2937 potential prescribing errors were identified in 400 medical records, primarily for the criteria “indication” (29%) and “interaction” (28%). Maximum severity was found for the criterion “contraindication” (sk = 2). The risk score was highest for the criterion “interaction” (rk = 3.1) and lowest for “dosage” (rk = 1.5). A total of 17% of physicians contacted replied.

Conclusions

A large number of potential prescribing errors were found. Medication analysis by experts combined with pharmacological consultation with the attending physicians were a valuable tool to detect potential prescribing errors and may help to improve medication safety.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Koper D, Kamenski G, Flamm M, et al. Frequency of medication errors in primary care patients with polypharmacy. Fam Pract. 2013;30:313–9.

Steinman MA, Landefeld CS, Rosenthal GE, et al. Polypharmacy and prescribing quality in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1516–23.

Tamblyn RM, McLeod PJ, Abrahamowicz M, et al. Do too many cooks spoil the broth? Multiple physician involvement in medical management of elderly patients and potentially inappropriate drug combinations. CMAJ. 1996;154:1177–84.

Green JL, Hawley JN, Rask KJ. Is the number of prescribing physicians an independent risk factor for adverse drug events in an elderly outpatient population? Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5:9–31.

World Health Organization. World report on ageing and health (2015). http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/186463/1/9789240694811_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 12 March 2018.

Rizza A, Kaplan V, Senn O, et al. Age- and gender-related prevalence of multimorbidity in primary care: the Swiss FIRE project. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:113. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-13-113.

Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;380:37–43.

Moriarty F, Hardy C, Bennett K, et al. Trends and interaction of polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate prescribing in primary care over 15 years in Ireland: a repeated cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008656. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008656.

Charlesworth CJ, Smit E, Lee DS, et al. Polypharmacy among adults aged 65 years and older in the United States: 1988–2010. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(8):989–95.

Aubert CE, Streit S, Da Costa BR, et al. Polypharmacy and specific comorbidities in university primary care settings. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;35:35–42.

Kirchmayer U, Mayer F, Basso M et al. Polypharmacy in the elderly: a population based cross-sectional study in Lazio, Italy. Eur Geriatr Med. 2016;484–87.

Schuler J, Dückelmann C, Beindl W, et al. Polypharmacy and inappropriate prescribing in elderly internal-medicine patients in Austria. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2018;120:733–41.

Haider SI, Johnell K, Thorslund M, et al. Trends in polypharmacy and potential drug–drug interactions across educational groups in elderly patients in Sweden for the period 1992–2002. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;45:643–53.

Kuijpers MA, van Marum RJ, Egberts AC, et al. Relationship between polypharmacy and underprescribing. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:130–3.

van den Heuvel PM, Los M, van Marum RJ, et al. Polypharmacy and underprescribing in older adults: rational underprescribing by general practitioners. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1750–2.

Schmiemann G, Bahr M, Gurjanov A, et al. Differences between patient medication records held by general practitioners and the drugs actually consumed by the patients. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;50:614–7.

Hummers-Pradier E, Bleidorn J, Schmiemann G, et al. General practice-based clinical trials in Germany: a problem analysis. Trials. 2012;13:205. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-13-205.

Martin-Facklam M, Rieger K, Riedel KD, et al. Undeclared exposure to St. John’s Wort in hospitalized patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;58:437–41.

Viktil KK, Blix HS, Moger TA, et al. Polypharmacy as commonly defined is an indicator of limited value in the assessment of drug-related problems. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:187–95.

Schmiedl S, Rottenkolber M, Hasford J, et al. Self-medication with over-the-counter and prescribed drugs causing adverse–drug-reaction-related hospital admissions: results of a prospective, long-term multi-centre study. Drug Saf. 2014;37:225–35.

Eickhoff C, Hammerlein A, Griese N, et al. Nature and frequency of drug-related problems in self-medication (over-the-counter drugs) in daily community pharmacy practice in Germany. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21:254–60.

Gandhi TK, Weingart SN, Borus J, et al. Adverse drug events in ambulatory care. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1556–64.

Thomsen LA, Winterstein AG, Sondergaard B, et al. Systematic review of the incidence and characteristics of preventable adverse drug events in ambulatory care. Ann Pharmacother. 2017;41:1411–26.

Mahler C, Jank S, Pruszydlo MG, et al. HeiCare(R): a project aiming to improve medication communication across health care sectors. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2011;1(36):2239–44.

van der Sijs H, Lammers L, van den Tweel A, et al. Time-dependent drug-drug interaction alerts in care provider order entry: software may inhibit medication error reductions. J Am Med Inf Assoc. 2009;16:864–8.

Ammenwerth E, Aly AF, Burkle T, et al. Memorandum on the use of information technology to improve medication safety. Methods Inf Med. 2014;53:336–43.

Pruszydlo MG, Walk-Fritz SU, Hoppe-Tichy T, et al. Development and evaluation of a computerised clinical decision support system for switching drugs at the interface between primary and tertiary care. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:137. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-12-137.

Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. Medicines Use Review (MUR): PSNC Main site, 2017. http://psnc.org.uk/services-commissioning/advanced-services/murs/. Accessed 18 August 2017.

Pharmaceutical Society of Australia Home Medicines Review (HMR). https://www.psa.org.au/content/aprc-home-medicines-review/. Accessed 18 August 2017.

pharmaSuisse Polymedikations-Check. http://www.pharmasuisse.org/de/1192/Polymedikations-Check.htm. Accessed 18 August 2017.

Schnurrer JU, Frölich JC. Incidence and prevention of lethal undesirable drug effects. Internist (Berl). 2003;44:889–95.

Laidig F. Evaluation einer Maßnahme zur Erhöhung der Arzneimitteltherapiesicherheit bei ambulanten Patienten (http://edok.bib.mh-hannover.de/ediss/diss-laidig.pdf). Dissertation, Institut für Klinische Pharmakologie, Medizinische Hochschule Hannover. 2015.

Boldt K. Entwicklung einer Vorgehensweise zur automatisierten Erkennung eines Bedarfs an klinisch-pharmazeutischer Betreuung aus GKV-Routinedaten mittels Data-Mining (https://elib.suub.uni-bremen.de/edocs/00104424-1.pdf). Dissertation, Universität Bremen, Zentrum für Sozialpolitik. 2015.

U.S. National Library of Medicine Home - PubMed - NCBI. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed. Accessed 18 August 2017.

Wolters Kluwer Health Intelligentere Entscheidungen. Bessere Behandlungsergebnisse. UpToDate. http://www.uptodate.com/de. Accessed 18 August 2017.

Rote Liste® Service GmbH. Suche, Schritt 1—FachInfo-Service, 2017. http://www.fachinfo.de/. Accessed 18 August 2017.

Holt S, Schmiedl S, Thürmann PA. Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: the PRISCUS list. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107:543–51.

Truven Health Analytics. Truven health products: micromedex solutions, (2017). https://www.micromedexsolutions.com/home/dispatch/ssl/true. Accessed 18 August 2017.

Dosing GmbH Heidelberg. AiDKlinik® Arzneimittel-Informations-Dienste, 2014. http://www.aidklinik.de/. Accessed 18 August 2017.

Lexi-Comp Inc. Lexi-Comp Online: Clinical Drug Information. http://www.wolterskluwercdi.com/lexicomp-online/. Accessed 19 March 2018.

Deutsches Institut für Medizinische Dokumentation und Informatik (DIMDI). DIMDI—ATC/DDD Anatomisch-therapeutisch-chemische Klassifikation mit definierten Tagesdosen, 2013. http://www.dimdi.de/static/de/amg/atcddd/index.htm. Accessed 22 February 2018.

Dean B, Barber N, Schachter M. What is a prescribing error? Qual Health Care. 2000;9:232–7.

Volkmann M. Delphi-Method. 2000. http://nosnos.synology.me/MethodenlisteUniKarlsruhe/imihome.imi.uni-karlsruhe.de/ndelphi_methode_b.html. Accessed 18 August 2017.

National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP). Types of Medication Errors - NCC MERP, 2017. http://www.nccmerp.org/types-medication-errors. Accessed 18 August 2017.

Bertsche T, Niemann D, Mayer Y, et al. Prioritising the prevention of medication handling errors. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30:907–15.

Health Canada. Guidance Document—Comparative Bioavailability Standars: Formulations Used for Systemic Effects, 2012. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/drug-products/applications-submissions/guidance-documents/bioavailability-bioequivalence/comparative-bioavailability-standards-formulations-used-systemic-effects.html. Accessed 18 August 2017.

Statistisches Bundesamt. Staat & Gesellschaft - Gesundheitszustand & -relevantes Verhalten - Körpermaße nach Altersgruppen und Geschlecht - Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis), 2013. https://www.destatis.de/DE/ZahlenFakten/GesellschaftStaat/Gesundheit/GesundheitszustandRelevantesVerhalten/Tabellen/Koerpermasse.html. Accessed 15 April 2018.

Slight SP, Howard R, Ghaleb M, et al. The causes of prescribing errors in English general practices: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:e713–20.

Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte (BfArM). BfArM—Weitere Arzneimittelrisiken—Metfomin: Aktualisierung der Fach- und Gebrauchsinformation hinsichtlich der Kontraindikation bei Patienten mit eingeschränkter Nierenfunktion, 2015. https://www.bfarm.de/SharedDocs/Risikoinformationen/Pharmakovigilanz/DE/RI/2015/RI-metformin.html. Accessed 18 August 2017.

Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte (BfArM). BfArM—Risikobewertungsverfahren—Metoclopramidhaltige Arzneimittel: Umsetzung des Durchführungsbeschlusses der EU-Kommission, 2014. http://www.bfarm.de/SharedDocs/Risikoinformationen/Pharmakovigilanz/DE/RV_STP/m-r/metoclopramid.html. Accessed 18 August 2017.

Kaufmännische Krankenkasse KKH. Pressekonferenz “Gesundheitscoaching” am 6. Mai 2015. https://www.kkh.de/content/dam/KKH/PDFs/Presse/PK%20Coaching%202015/Statement%20Kailuweit%20Coaching.pdf; Accessed 27 August 2017.

Grandt D, Friebel H, Mueller-Oerlinghausen B. Arzneimitteltherapie(un)sicherheit. DÄBl. 2015;102:A509–15.

Acknowledgements

The study was conducted based on “Arzneimittel sicher anwenden”, a project launched by KKH, a German statutory health insurance. DOS coordinated the project together with Lutz Herbarth (PhD, KKH). MM, JB, FL and DOS carried out the medication analyses. FL, MM, JB, NS and DOS assessed the reliability of the underlying data. MM, JB, Christoph Schröder (docent, Institute of Clinical Pharmacology, MHH), Jens Tank (professor, Institute of Clinical Pharmacology, MHH), Stefan Engeli (professor, Institute of Clinical Pharmacology, MHH) and DOS rated the severity of the PPEs as members of the Delphi method.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FL was responsible for the study concept, acquired the data, carried out the statistical analysis, interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of Hannover Medical School (no: 1637-2012) according to German regulations. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Formal consent is not required for this type of study. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent to participate

Informed consent from participants was not required as the retrospective study design did not affect the healthcare of included patients. All personal data were subjected to pseudonymization, and retracing was not possible without the pseudonym key. All data were analysed anonymously.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Conflict of interest

Friederike Laidig, Marcus May, Julia Brinkmann, Nils Schneider and Dirk O. Stichtenoth have no conflicts of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Laidig, F., May, M., Brinkmann, J. et al. Evaluation of potential prescribing errors in patients with polypharmacy: a method to improve medication safety in ambulatory care. Drugs Ther Perspect 34, 322–334 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-018-0507-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-018-0507-1