Abstract

Biologics are increasingly vital medicines that significantly reduce morbidity as well as mortality, yet access continues to be an issue even in apparently wealthy countries, such as the USA. While patient access is expected to improve with the introduction of biosimilars, misperceptions in a significant part based on terminology continue to make a sustained contribution by biosimilars difficult. Patients are and will continue to suffer needlessly if biosimilars continue to be impugned. Consequently, it is increasingly urgent that semantics are clarified, and in particular, the implication that interchangeable biologics are better biosimilars dismissed. This paper distinguishes between the real differences between biologics that matter clinically to patients and discusses the actual meaning of a US Food and Drug Administration designation of interchangeability for a biosimilar product. This will help highlight where there is need for further Food and Drug Administration education and which stakeholders likely need that education the most.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Clinicians can prescribe biosimilars just like any other medicine for any purpose; the US Food and Drug Administration designation of interchangeability enables pharmacists (subject to state law) to substitute a biosimilar in lieu of its reference without prior approval from the prescriber. Food and Drug Administration education on this distinction, that interchangeability is about dispensing and not prescribing, would be valuable. |

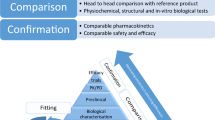

Comparability, initiated by the Food and Drug Administration in 1996 through guidance and formalized as ICH Q5E, established that manufacturing changes to biologics can be undertaken without changes to the product itself. This is confirmed by analytics, rarely any clinical studies, and presupposes extrapolation and interchangeability. There are no label changes, and neither patients nor their providers are told such changes have occurred. |

Once any biologic is approved, complexity per se is no longer relevant because the regulators have determined that the product can be manufactured consistently in a well-controlled manner. This includes current good manufacturing practices, which are already the norm for all biologics and therefore have also always applied to biosimilars. |

Multiple sponsors of medicines containing the same (generic) or highly similar (biosimilar) active ingredients increase access and affordability, increasing surety of supply, just as for any other commercial product in a competitive marketplace. This can create savings. |

1 Introduction

Biologics are increasingly fundamental to good medical care for many chronic and acute diseases [1], but they can be expensive and specialty products are underutilized as a result [2]. Disability and death occur, leading to suffering and loss of productivity when optimal treatments are denied or delayed. Public health is compromised and this is as true in the USA as the rest of world given the variability in access to quality and timely healthcare.

Efficiencies in biologic development and manufacturing (including regulatory oversight) can allow the greater use of biologics while appropriate quality is maintained. Then, biologics become more affordable with more patients able to access them and earlier in disease progression, which is important for debilitating/progressive/fatal diseases [3]. Lack of access to specialty medicines is an unmet medical need, and competition can change this [4].

Biosimilars can help solve these problems, which was the goal of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCIA) [5], enacted as Title VII of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act [6] on 23 March, 2010 (also known as “Obama Care”). Congress and President Biden sought further appreciation of their value with the Advancing Education on Biosimilars Act of 2021 [7], enacted on 23 April, 2021, “which authorizes the Food and Drug Administration to educate consumers and health care providers on biologic products, including biosimilars”.

2 Background

Biologics have been around since 1796 [8], historically with vaccines and naturally sourced products, and more recently with recombinant proteins and cell and gene therapies. In the USA, biologics are regulated under the Public Health Service Act (PHS Act) [9]. This is a separate statute from that for small-molecule drugs, which are approved under the later Federal Food Drug and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) [10]. It is also independent of the underlying science, and simply a relic of history. Most jurisdictions have a single law governing all pharmaceutical products. However, this distinction in the USA, plus delays in the availabilities of biosimilars, has contributed to suppositions that subsequent versions of biologics from different sponsors were not possible. Hence, in the USA, we have had generic drugs (access increased by Hatch Waxman 1984 [11]) well ahead of biosimilars (BPCIA 2010 [5]) but not “generic biologics” (deemed unacceptable terminology because of the conflation of regulatory expectations with those of generic small-molecule drugs). Yet, the USA leads the world on originator drugs and biologics, as well as with generic adoption/access, thus the economic and public health opportunity is commensurately huge [12].

The legal distinctions haunt our regulatory approaches to biologics to this day in the USA, despite Dr. Janet Woodcock’s Congressional testimony in 2007 observing that some drugs remain more complex than some biologics [13]. Whereas, as a scientific matter, complexity is a continuum (we even have some drugs still made from biologic sources, e.g., enoxaparin [14] and some products that are biologics as a scientific matter that had been regulated as drugs but were deemed to be biologics as a regulatory matter on 23 March, 2020, including the first interchangeable biologic, insulin [15, 16]), there remains a bright line statutorily. Namely, at any given time in the USA, a product is either approved as a drug under the Federal Food Drug and Cosmetic Act or licensed as a biologic under the PHS Act.

In no case is quality an issue per se for biosimilars given that all US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-licensed biologics, and indeed all FDA-approved drugs, are required to comply with current Good Manufacturing Practices [17] to ensure manufacturing consistency and dependable control of quality irrespective of the sponsor or business model. Suggestions have been made that biosimilars, as “copies,” corner cut on quality [18, 19]. There is absolutely no compromise in quality [17] and this is an entirely separate issue from the biosimilar analytic match to its reference. This is a further example of how precisely words must be used [20].

The legal definition in BPCIA for an interchangeability designation is that the biologic meets the follow criteria [5]:

(4) SAFETY STANDARDS FOR DETERMINING INTERCHANGEABILITY.—Upon review of an application submitted under this subsection or any supplement to such application, the Secretary shall determine the biological product to be interchangeable with the reference product if the Secretary determines that the information submitted in the application (or a supplement to such application) is sufficient to show that—

(A) the biological product—

(i) is biosimilar to the reference product; and

(ii) can be expected to produce the same clinical result as the reference product in any given patient; and

(B) for a biological product that is administered more than once to an individual, the risk in terms of safety or diminished efficacy of alternating or switching between use of the biological product and the reference product is not greater than the risk of using the reference product without such alternation or switch.

An FDA interchangeability designation allows the substitution by a pharmacist (subject to state law) of a biosimilar for its reference originator biologic without consulting the original prescriber [5]—nothing more and nothing less—and as such is a legal distinction. An interchangeable biologic is a biosimilar upon which additional studies may have been conducted and not a wholly new product [21, 22], i.e., it is the same Biologics License Application.

3 Discussion

Regulators, especially the FDA, function within the authorities given to them by statute. Sometimes, this allows regulatory initiatives not otherwise specified in the law, for example, the FDA’s comparability guidance in 1996 [23]. In general, absent a public health disaster, the FDA evaluates medicines made available to the US public and states recognize the FDA’s determinations of safety, efficacy, and quality. Courts enforce the FDA’s authorities but usually defer to the FDA’s judgment on scientific matters. This will likely include any determination of interchangeability for a biologic (just as is the case for therapeutic equivalence for a generic small-molecule drug). Occasionally public health emergencies, such as the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, alter the standard steps in product development, and exceptional powers are invoked such as emergency use authorizations [24]. This is rare.

However, history matters. The US precedent of regulating drugs and biologics under different statutes was interpreted by the FDA to allow generic small-molecule drugs, but not to support anything similar for biologics [25] (even though the flexibility of the PHS Act was arguably already there, and even though aspects of Hatch Waxman were already applied to PHS Act licensed biologics, such as patent term extensions [11], as well as insulins and other biologics being regulated as drugs [15]). Nonetheless, the FDA is being largely consistent in approaches to generics and biosimilars where reasonable to do so (e.g., labeling). The FDA shows particular respect to its own precedents [25]. The FDA has published guidance for biosimilars and this continues to evolve [26].

The European Union (EU) took a different approach, both with their guidelines (2003 comparability applied intra-sponsor and inter-sponsor [27]) and in terms of their pharmaceutical legislation more generally, in which a single statute encompasses both drugs and biologics even as it was revised in 2004 to enable biosimilars [28]. However, the same regulatory science was applied [29], and subsequently adopted by the World Health Organization [30]. The common science being applied allows the EU experience with biosimilars to be relevant in the USA. European Union regulators have stated that they consider all their approved biosimilars to be interchangeable as a clinical matter [31]. While not a legal designation in Europe, this is a scientific one with clinical ramifications.

The FDA did not adopt an oversight role on biosimilars until the new regulatory pathway for them was explicitly created in BPCIA in 2010 [5]. In that law, an additional category of interchangeable biologics was created that is not given to any other regulatory authority in the world. This was not because biosimilars would not be interchangeable as a clinical matter, but because the states adjudicate substitution of products by other than the prescriber through their practice of pharmacy laws and an official FDA designation was expected to be helpful in those circumstances where pharmacy substitution could apply (much like occurs for generic drugs under Hatch Waxman 1984 [11]). Substitution is not a federal decision (any more than it is a European Commission decision) because the FDA does not regulate the practice of pharmacy. Nor does the FDA regulate the practice of medicine in which a prescription medicine can be prescribed for any purpose, including beyond the FDA label, subject to state law.

Biosimilars in USA are never “not interchangeable” to the extent that they are just not yet designated as interchangeable by the FDA. This situation for biosimilars is very like that under the EU law, which is silent on interchangeability. While the first step to biosimilarity is essentially the same in the EU and the USA, the second step of an interchangeability designation is simply available in the USA and not in the EU (where such decisions are country based like all healthcare and not an authority awarded centrally to the European Medicines Agency).

For most biologics, given their special attributes (such as particular care on storage and transport temperature limitations and rarely administered orally), the prescriber is usually responsible for their administration to the patient. As such, an opportunity for substitution by other than the prescriber does not exist. However, in a few cases, patients do administer their own biologic medicines (e.g., insulin, adalimumab, etanercept) and in these cases there may be an opportunity for generic-type substitution at a pharmacy.

That physicians might themselves perceive the need for an interchangeability designation to assist in their own decisions to switch patients was not a consideration during the drafting of the legislation, and there was no suggestion that interchangeable biologics were better biosimilars. Afterall, a physician can use a medicine on or off label as appropriate to the patient, and have routinely switched products, even closely related ones, as a means to optimize care. Physicians in the USA can preclude substitution of any drug or biologic on any prescription they write, although this may lead to additional requirements with payers if the medicine they prefer is not on the available formulary. However, physicians may be vulnerable to misinformation especially when a new brand name appears [19, 32].

The creation of a new legal term of art “interchangeable” in BPCIA, applicable only to substitution at the pharmacy level, has caused general confusion. This is because the word also has common usage and is generally applied by the leading biosimilar regulator, the European Medicines Agency, to indicate “the possibility of exchanging one medicine for another medicine that is expected to have the same clinical effect” [33]. This applies to every biosimilar. Indeed, the European regulators, in their independent capacities, have observed that all of their biosimilars are already interchangeable by this definition, and as such they can be switched for their reference in the practice of medicine [31] (as opposed to legally substitutable by other than the prescriber, which is not a European Commission decision). The FDA has agreed with this conclusion for the purposes of physician prescribing [34]. As a clinical matter, the outcomes for the patient will be the same whether the switch is made by the physician or pharmacist, but the authorities are quite distinct as a legal matter. Some countries are choosing to impose such switches, either centrally or regionally, for economic reasons, but ultimately in each case a physician must write the prescription [35].

However, just as quality and good manufacturing control is important for every biologic, the same concept of comparability between manufacturing changes can be applied between the reference and the biosimilar [36]. Different versions of the originator products have been interchangeably used by both definitions—both clinically and at the pharmacy level—usually unconsciously; and based on less substantiated data than are required for a biosimilar. They are expected to have no clinically meaningful impact, and only rarely have done so [37, 38]. Similarly, experience with naïve patients and patients already established on a biologic who are switched to another product (reference biologic or any biosimilar to that reference) has also shown no change in clinical outcomes [39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. Likewise, no evidence has been presented showing a concern when switching between biosimilars to the same reference product. As a scientific matter, given that biosimilars are each comparable to their reference products they are also comparable to each other, just as any given biologic is to itself over time, hence building a bridge all the way back to the clinical studies on the originally approved biologic upon which they all depend [46, 47]. As such, no exceptional issues would be expected for any biosimilar any more than we do for any biologic over its lifetime.

4 Conclusions

All biosimilars approved in the highly regulated markets using the scientific standard of comparability are interchangeable with their reference products (and each other) as a clinical matter. Analytical differences will be understood and known not to alter the clinical outcome, just as is the case for manufacturing changes today [48]. This is the strength of comparability based on fit-for-purpose analytics and the importance of its application consistently by regulators to all biologics independent of the sponsors business model [36].

The decision to switch patients may be made centrally in some highly regulated markets using national formulary and country or regional purchasing decisions. This is supported by the regulatory science of their approval being consistent. The FDA already considers itself as the “gold standard” in this regard and led with the core principles in 1996. That the science is global, increasingly harmonized, and that the experience with the same biologics in different countries has been consistent with expectations also gives great confidence in future regulatory reliance [49]. The USA is unique only to the extent that there is the additional opportunity created by statute for a formal designation of interchangeability on the label of the 351(k) biosimilar, and a listing in the Purple Book [50] to facilitate such switches by other than the original prescriber. The product itself is the same. The distinction of the FDA interchangeability designation is purely legal, and is limited to biosimilars, meaning that no reference biologic can ever be designated as interchangeable.

For every FDA-licensed biosimilar, physicians and their patients can have as much confidence as they historically have had with the originator product in switching the care for any given patient between any biosimilar to the same reference, and with that same reference itself. Each will provide optimal care of that patient provided consistent and timely access is enabled. As such, as a clinical matter, all biosimilars are interchangeable. As a legal matter, the FDA designation may be of value in allowing pharmacists to substitute those few biologics that are self-administered for their reference originator biologic.

References

US FDA. “What are “biologics” questions and answers”. https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/center-biologics-evaluation-and-research-cber/what-are-biologics-questions-and-answers. Accessed 11 Feb 2022.

Patel BN, Audet PR. A review of approaches for the management of specialty pharmaceuticals in the United States. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32:1105–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-014-0196-0.

Avalere. Use of step through policies for competitive biologics among commercial US insurers. 2018. https://img04.en25.com/Web/AvalereHealth/%7B693465f5-4dad-4776-95f4-f2ad009a49b1%7D_Use_of_Step_Through_Policies_for_Competitive_Biologics_Among_Commercial_US_Insurers.pdf. Accessed 11 Feb 2022.

Stucke ME. Is competition always good? J Antitrust Enforce. 2013;1(1):162–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/jaenfo/jns008.

US FDA. Implementation of the Biosimilars Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/guidance-compliance-regulatory-information/implementation-biologics-price-competition-and-innovation-act-2009. Accessed 11 Feb 2022.

Congress. (2010, March 22). H.R. 3590 (ENR). Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. U.S. Government Publishing Office. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/BILLS-111hr3590enr. Accessed 28 May 2022.

The White House signed S. 164, the “Advancing Education on Biosimilars Act of 2021,” on 23 April 2021, “which authorizes the Food and Drug Administration to educate consumers and health care providers on biologic products, including biosimilars”. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/legislation/2021/04/23/bills-signed-s-164-s-415-s-422-s-578/. Accessed 11 Feb 2022.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. History of smallpox. https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/history/history.html. Accessed 11 Feb 2022.

House of Representatives, Congress. (2010). 42 U.S.C. 262. Regulation of Biological Products. U.S. Government Publishing Office. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCODE-2010-title42/USCODE-2010-title42-chap6A-subchapII-partF-subpart1-sec262. Accessed 11 Feb 2022.

US FDA. Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act). https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/laws-enforced-fda/federal-food-drug-and-cosmetic-act-fdc-act. Accessed 11 Feb 2022.

US FDA. Hatch Waxman letters. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/abbreviated-new-drug-application-anda/hatch-waxman-letters. Accessed 11 Feb 2022.

OECD. Health at a glance 2021: OECD indicators: highlights for the United States. https://www.oecd.org/unitedstates/health-at-a-glance-US-EN.pdf. Accessed 11 Feb 2022.

Woodcock J. Assessing the impact of a safe and equitable biosimilar policy in the United States: hearing before the Subcommittee on Health, House Committee on Energy and Commerce. 2 May 2007.

US FDA. Generic enoxaparin questions and answers. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/generic-enoxaparin-questions-and-answers. Accessed 11 Feb 2022.

George K, Woollett G. Insulins as drugs or biologics in the USA: what difference does it make and why does it matter? BioDrugs. 2019;33:447–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-019-00374-1.

Woollett G. The FDA just broke the logjam on interchangeable biologics. Here’s what that decision means. STAT. 2021. https://www.statnews.com/2021/07/29/fda-first-interchangeable-biologic-insulin-decision-meaning/. Accessed 28 May 2022.

US FDA. Facts About the current good manufacturing practices (CGMPs). https://www.fda.gov/drugs/pharmaceutical-quality-resources/facts-about-current-good-manufacturing-practices-cgmps. Accessed 11 Feb 2022.

PhRMA. Biologics & biosimilars. https://www.phrma.org/policy-issues/research-and-development-policy-framework/biologics-biosimilars. Accessed 11 Feb 2022.

Cohen HP, McCabe D. The importance of countering biosimilar disparagement and misinformation. BioDrugs. 2022;34:407–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-020-00433-y.

US FDA. FDA and FTC announce new efforts to further deter anti-competitive business practices, support competitive market for biological products to help Americans. 2020. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-and-ftc-announce-new-efforts-further-deter-anti-competitive-business-practices-support. Accessed 11 Feb 2022.

US FDA. Guidance for industry: considerations in demonstrating interchangeability with a reference product. 2019. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/considerations-demonstrating-interchangeability-reference-product-guidance-industry. Accessed 11 Feb 2022.

US FDA. Draft guidance for industry: clinical immunogenicity considerations for biosimilar and interchangeable insulin products. 2019. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/clinical-immunogenicity-considerations-biosimilar-and-interchangeable-insulin-products. Accessed 11 Feb 2022.

US FDA. Guidance for industry: demonstration of comparability of human biological products, including therapeutic biotechnology-derived products. 1996. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/demonstration-comparability-human-biological-products-including-therapeutic-biotechnology-derived. Accessed 11 Feb 2022.

US FDA. Emergency use authorization. https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/mcm-legal-regulatory-and-policy-framework/emergency-use-authorization. Accessed 11 Feb 2022.

Woodcock J, Griffin J, Behrman R, Cherney B, Crescenzi T, Fraser B, et al. The FDA’s assessment of follow-on protein products: a historical perspective. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6(6):437–42. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd2307.

US FDA. Biosimilars guidances. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/general-biologics-guidances/biosimilars-guidances. Accessed 29 Apr 2022.

EMEA CHMP. Guideline on comparability of medicinal products containing biotechnology-derived proteins as active substance: quality issues. 2003. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/comparability-medicinal-products-containing-biotechnology-derived-proteins-active-substance-quality/ich/5721/03_en.pdf. Accessed 11 Feb 2022.

Directive 2004/27/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 March 2004 amending Directive 2001/83/EC on the community code relating to medicinal products for human use. Available from:https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32004L0027&from=EN. Accessed 28 May 2022.

European Medicines Agency. Multidisciplinary: biosimilar guidelines. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/research-development/scientific-guidelines/multidisciplinary/multidisciplinary-biosimilar. Accessed 28 May 2022.

WHO. Guidelines on evaluation of similar biotherapeutic products (SBPs). 2009. https://www.who.int/biologicals/areas/biological_therapeutics/BIOTHERAPEUTICS_FOR_WEB_22APRIL2010.pdf . [Accessed 11 Feb 2022]. (To be replaced by the version adopted by the Seventy-fifth meeting of the World Health Organization Expert Committee on Biological Standardization, 4–8 April 2022: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/biologicals/bs-documents-(ecbs)/annex-3---who-guidelines-on-evaluation-of-biosimilars_22-apr-2022.pdf?sfvrsn=e127cbf4_1&download=true. Accessed 29 Apr 2022.

Kurki P, van Aerts L, Wolff-Holz E, Giezen T, Skibeli V, Weise M. Interchangeability of biosimilars: a European perspective. BioDrugs. 2017;31:83–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-017-0210-0.

Feagan BG, Marabani M, Wu JJ, Faccin F, Spronk C, Castañeda-Hernández G. The challenges of switching therapies in an evolving multiple biosimilars landscape: a narrative review of current evidence. Adv Ther. 2020;37:4491–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-020-01472-1.

European Medicines Agency and the European Commission. Biosimilars in the EU information guide for healthcare professionals. 2019. https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/leaflet/biosimilars-eu-information-guide-healthcare-professionals_en.pdf. Accessed 11 Feb 2022.

Kirkner RM. FDA’s Gottlieb aims to end biosimilars groundhog day. Managed care. 2019. https://lscpagepro.mydigitalpublication.com/publication/index.php?m=38924&i=562686&p=6&ver=html5. Accessed 14 Feb 2022.

Fisher A, Kim JD, Carney G, Dormuth C. Rapid monitoring of health services use following a policy to switch patients from originator to biosimilar etanercept: a cohort study in British Columbia. BMC Rheumatol. 2022;6(1):5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41927-021-00235-x.

Webster CJ, George KL, Woollett GR. Comparability of biologics: global principles, evidentiary consistency and unrealized reliance. BioDrugs. 2021;35:379–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-021-00488-5.

Boven K, Stryker S, Knight J, Thomas A, van Regenmortel M, Kemeny DM, et al. The increased incidence of pure red cell aplasia with an Eprex formulation in uncoated rubber stopper syringes. Kidney Int. 2005;67(6):2346–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00340.x.

Lüftner D, Lyman GH, Gonçalves J, Pivot X, Seo M. Biologic drug quality assurance to optimize HER2+ breast cancer treatment: insight from development of the trastuzumab biosimilar SB3. Target Oncol. 2020;15:467–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11523-020-00742-w.

Cohen HP, Blauvelt A, Rifkin RM, Danese S, Gokhale SB, Woollett G. Switching reference medicines to biosimilars: a systematic literature review of clinical outcomes. Drugs. 2018;78:463–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-018-0881-y.

Barbier L, Ebbers HC, Declerck P, Simoens S, Vulto AG, Huys I. The efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of switching between reference biopharmaceuticals and biosimilars: a systematic review. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2020;108(4):734–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.1836.

Luber R, O’Neill R, Singh S, Arkir Z, Irving P. P485 Switching infliximab biosimilar: no adverse impact on inflammatory bowel disease control or drug levels with the first or second switch. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:S426–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz203.614.

Macaluso FS, Fries W, Viola A, Centritto A, Cappello M, Giuffrida E, et al. P425 SPOSIB SB2: a Sicilian prospective observational study of patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with infliximab biosimilar SB2. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:S387–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz203.554.

Mazza S, Fascì A, Casini V, Ricci C, Munari F, Pirola L, et al. P360 Safety and clinical efficacy of double switch from originator infliximab to biosimilars CT-P13 and SB2 in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (SCESICS): a multicentre study. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:S342. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz203.489.

Lauret A, Molto A, Abitbol V, Gutermann L, Conort O, Chast F, et al. Effects of successive switches to different biosimilars infliximab on immunogenicity in chronic inflammatory diseases in daily clinical practice. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2020;50(6):1449–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.02.007.

Ilias A, Szanto K, Gonczi L, Kurti Z, Golovics PA, Farkas K, et al. Outcomes of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases switched from maintenance therapy with a biosimilar to remicade. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(12):2506–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2018.12.036.

Webster CJ, Woollett GR. A ‘global reference’ comparator for biosimilar development. BioDrugs. 2017;31:279–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-017-0227-4.

Webster CJ, Wong AC, Woollett GR. An efficient development paradigm for biosimilars. BioDrugs. 2019;33:603–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-019-00371-4.

FDA. Guidance for industry: Q5E comparability of biotechnological/biological products subject to changes in their manufacturing process. 2005. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/q5e-comparability-biotechnologicalbiological-products-subject-changes-their-manufacturing-process. Accessed 28 May 2022.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Regulating medicines in a globalized world: the need for increased reliance among regulators. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2020. https://doi.org/10.17226/25594.

US FDA. Purple book: lists of licensed biological products with reference product exclusivity and biosimilarity or interchangeability evaluations. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/therapeutic-biologics-applications-bla/purple-book-lists-licensed-biological-products-reference-product-exclusivity-and-biosimilarity-or. Accessed 29 Apr 2022.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work was funded by Samsung Bioepis Co., Ltd.

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

JPP, BJ, HKP, DS, JAJ, JG, JH, KK, and GRW are employees of Samsung Bioepis Co., Ltd.

Ethics approval

No patient data were accessed; therefore, no ethical review board review was required.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to concepts used to build the manuscript and editing of the manuscript. The main text of the paper was written by GRW and JPP. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, J.P., Jung, B., Park, H.K. et al. Interchangeability for Biologics is a Legal Distinction in the USA, Not a Clinical One. BioDrugs 36, 431–436 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-022-00538-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-022-00538-6