Abstract

Purpose of Review

Oncologists are often extremely hesitant to provide life expectancy to patients, their families, and rehabilitation clinicians who need this data to develop a realistic and compassionate plan of care. This review will discuss the art and science of determining prognosis for patients considered for admission to an inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF).

Recent Findings

Oncologist overestimate prognosis by as much as fivefold and generally communicate a significantly longer life expectancy to patients and families. Patients with active cancer requiring maximal assistance on admission to an IRF have a nearly 60% chance of acute care discharge.

Summary

This paper will discuss the art and science of using prognostic determination as a key component of making good decisions with respect in the admission of cancer patients to IRF. Prognosis is best determined prior to admission by rehabilitation professionals based on a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s oncologic history, functional status, and importantly presence or absence of meaningful treatment options. Patients with extremely limited life expectancy should only be admitted on a supportive pathway intent on expeditious discharge home with hospice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite considerable data supporting the benefits, admission of cancer patients to inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRF) can be a great source of trepidation for the rehabilitation team [1,2,3,4,5]. Such patients are often extremely ill, medically complex, and subsequently have a high rate of acute care transfer (ACT) and death compared with other cohorts [6, 7]. Because of their severe medical compromise, compliance with the 3 h daily of rehabilitation mandate for IRF is often hindered [8]. A retrospective study of data pulled from the Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation identified 115,570 adults admitted to IRF during the 13-year period from 2002 to 2014 [2]. Of these patients, 17% were discharged to an acute hospital and 0.48% died while at the rehabilitation facility [2]. A retrospective review categorized the most common medical complications necessitating ACT as electrolyte abnormalities, musculoskeletal, genitourinary or renal, hematologic, and cardiovascular [9]. A secondary analysis of a retrospective study of 163 cancer patients admitted to IRF found that approximately one in six patients died within 2 months of discharge [10]. Because of these well-known issues, admission decision-making for this cohort is extremely challenging and many IRF are reluctant to take patients with advanced cancer. For centers such as ours which do accept cancer patients, even those with advanced disease in specific situations, the ACT rate may be significantly higher.

Because inpatient rehabilitation typically focuses on restoring patients with a monophasic event such as a stroke or spinal cord injury to their highest functional level, rehabilitation clinicians often do not have a clear vision of the goals of admission for cancer patients, particularly for patients with advanced and progressive cancer. This challenges their ability to formulate a safe, effective, compassionate, and realistic rehabilitative plan of care. This review will discuss the art and science of using prognostic assessment as a major component of making good decisions with respect to the admission of cancer patients to IRF. The key components of medical and oncologic history and their paramount importance in determining if a given patient has meaningful treatment options will be discussed. It is not necessary for rehabilitation clinicians to predict prognosis with extreme accuracy. It is enough to identify patients that are actively dying within days or weeks so that an appropriate rehabilitation plan of care can be crafted. Even patients near the end of life may be excellent candidates for IRF provided the patient, their caregivers, and the rehabilitation team have a clear and realistic understanding of the goals for admission. Properly done, such admissions can be extremely gratifying for the staff and provide patients with the strategies, training, and equipment they need to spend their final days at home with their loved ones. Providing rehabilitation in this context represents a major departure from traditional rehabilitation goals and requires a redefinition of what is considered “success.” Success is not returning the patient to the highest level of function, but equipping them to “die well”—as functionally and comfortably as possible—at home.

What Patients Want to Know

Prognosis seems to be one of the most closely guarded secrets in medicine. Accurately determining life-expectancy in the cancer rehabilitation setting is critical to creating a realistic and compassionate plan of care. The oncology team is notoriously guarded when it comes to sharing this information with the patient, their family, and even colleagues [11]. “We don’t want to crush their hope,” or a similar refrain, is a commonly expressed sentiment. While there are some patients and families that understandably avoid processing and internalizing their situation as an adaptive response, most report wanting a realistic prognosis. In a survey of 126 patients just diagnosed with cancer, 98% wanted their doctor to be realistic about the prognosis and provide an opportunity to have their questions answered [12]. In an analysis of 590 patients with advanced cancer, 71% wanted to know their life expectancy but only 18% recalled it being provided by their physician [13].

When doctors do render a prognosis for terminally ill cancer patients, they usually overestimate prognosis by a significant amount. In a prospective study of physicians estimating life expectancy in terminally ill patients at the time of hospice referral, they overestimated survival by a factor of 5.3 [14]. In cases where the clinician does estimate prognosis, there is tremendous, and typically optimistic disparity in what is communicated to the patient. In one study, clinicians estimating a formulated median prognosis of 75 days to live would communicate 90 days to the patient but the actual survival was only 26 days [15].

Predictors of Survival in Advanced Cancer

There are many ways to predict prognosis in patients with advanced cancer including clinical signs and symptoms, various integrated prognostic models, and performance status. One online tool (cancersurvivalrates.com) provides evidenced-based approximation of survival scenarios based on the patients sex and age as well as the cancer type, stage, grade, histology, and when it was diagnosed. This tool is useful to provide a baseline understanding of the patient’s status when considering IRF admission. Prognostic determinations based only on intuition and clinical experience are almost always overly optimistic [14, 16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. Generally speaking, integrated prognostic models are cumbersome, tailored to specific cancer types, and may incorporate data that may not readily available to clinicians making a determination of a given patient’s appropriateness for admission to IRF. Clinical signs and symptoms were first described as independent prognostic factors in 1966 [28]. A qualitative systematic review evaluating over 100 variables from 22 studies of patients the advanced cancer reported that, following performance status, certain discrete signs and symptoms including dyspnea, dysphagia, weight loss, xerostomia, anorexia and cognitive impairment, were the best predictors of patient survival [29]. Interestingly, the “surprise question,” often stated as “Would you be surprised if this patient died in the next year?” is based on an amalgamation of the clinicians understanding of the patient’s clinical status and can incorporate an in-depth and informed understanding of their history, current signs, symptoms, and other factors. It has been demonstrated to have particularly good utility in patients with advanced cancer [30,31,32]. In the IRF setting, a shorter time interval such as “Would you be surprised if this patient died in the next month,” though untested in the literature, has been found to be useful for the rehabilitation staff our institution. If the answer to this question is “no,” then the admission team should critically examine the goals for potential admission to ensure they are realistic and obtainable.

Performance Status

Improving function and quality of life is foundational to cancer rehabilitation [33]. Performance status, or the measure of a patient’s functional capacity (i.e., mobility, activities of daily living), has been repeatedly found to predict survival in patients with cancer [34]. Performance status is used in oncology, not only to predict prognosis, but also to evaluate a given patients suitability for certain therapies and in clinical trials as inclusion/exclusion criteria [34]. A number of instruments have been developed to evaluate and quantity performance status including the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status and the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) Scale [34].

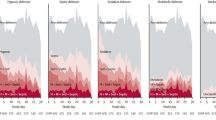

KPS is reported from 0 (dead) to 100 (normal). The power of KPS and other performance status measures to predict prognosis in patients with advanced cancer was demonstrated by Jang et al. [35]. In a cohort of 1655 patients admitted for palliative care planning, the investigators found patients with median survival times, in days, for patients with KPS 80–100 of 215 days, KPS 60–70 of 119 days, KPS 40–50 of 49 days, and KPS 10–30 of 29 days (Fig. 1).

The elegance, simplicity, and potential utility of KPS as a tool to inform IRF admission decisions for cancer patients was recognized by the author and put into clinical practice using a translation of the original KPS to a format more familiar and suitable to rehabilitation clinicians (Fig. 2) [6]. This KPS translation was validated at three time points (premorbid, admission, and discharge) and found to have acceptable interrater reliability [6]. KPS was then evaluated in a series of 416 patients with active cancer admitted to three of our IRF facilities [7]. One in five patients (21.2%) in the cohort required ACT. Those with a KPS score of 40 (defined as requiring maximal assistance) had the highest ACT rate (59.1%). Patients with hematologic malignancies had the highest rate of ACT (HR = 2.36, SE = 0.834, p = 0.15, 95% CI 1.18–4.72) and there was a non-statistically significant trend of increasing ACT risk for patients with solid tumor based on their metastatic burden from no metastases (HR = 1.46), one metastasis (HR = 1.54), to multiple metastasis (HR = 1.70). Mortality during and within days and weeks of IRF was extremely high in this cohort but has yet to be reported in the literature.

Clinical Evaluation

The importance of a thorough understanding of a patient’s medical and oncologic history prior to accepting them for admission to IRF cannot be overstated. Though simple conceptually, in practice, clinical liaisons and other clinicians making such determinations often fail to identify, record, understand, interpret, and incorporate key components of the patient’s history. Basic data points including the date of initial diagnosis, cancer type, how the diagnosis was made, the cancer’s location, stage, history, and receptor status may be disregarded by a clinician unfamiliar with the complexities of cancer. Critically, aspects of the patient’s treatments, both initial and for recurrence, including surgery, systemic therapy, and radiation therapy are not afforded due diligence, especially to uninitiated reviewers. Even more importantly, the patient’s and tumor’s response, or likely response, to treatment is not adequately considered. For instance, a patient with newly diagnosed prostate cancer who presents with paraplegia due to metastatic disease has a very different oncologic and functional prognosis compared with one diagnosed years ago and who has received, and ultimately failed, all available treatment options. The former patient may have years of life expectancy, even as paraplegic, whereas the latter patient may have a life expectancy measured in days.

Meaningful Treatment Options

A core consideration in predicting prognosis in cancer patients evaluated for IRF admission, and a phrase that has become a mantra at our institutions, is the presence of “meaningful treatment options.” As with the example above, it is the presence of meaningful treatment options that are a key differentiator making the first patient a good IRF candidate and the latter one a dubious one. It is not enough that the patient’s cancer responds to the treatment; the patient must also be able to tolerate the treatment. A frail patient with multiple medical comorbidities is not likely to do well with systemic chemotherapy. In fact, the side effects of the chemotherapy may be more toxic and life-threatening than not treating the cancer. This was convincingly illustrated by the seminal Temel trial evaluating the benefits of early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer [36]. The patients receiving early palliative care had significant improvements in quality of life and mood and, because they had less aggressive care at end of life, lived longer. It is common to have patients referred for IRF because of hospitalization for severe treatment-related adverse outcome such as infection, respiratory failure, and cerebrovascular accident. The referring team may intimate that they would “like to get the patient strong enough for additional chemotherapy.” This sentiment should ALWAYS raise a red flag and prompt the IRF team to question if such a patient has the potential to reach a suitable functional status for additional therapy and, as importantly, why the patient will not suffer the same outcome when challenged with toxic treatment again [37].

Owning Prognostic Determination

Oncologists are often reluctant to share a life expectancy prognosis with the clinicians determining a patient’s suitability for IRF admission. The hospitalists tasked with caring for the patient in the acute care facility likewise may not know or be disinclined to share this information. Expeditiously discharging patients from the acute care setting is incentivized financially in our current payer models; as such, it may impact what information is shared by an acute care team under pressure to move patients out of the hospital.

Frustration with our inability to reliably get prognostic information for patients under consideration for IRF admission has forced us to make the determination ourselves. This determination is heavily based, as described above, on identifying, recording, understanding, interpreting, and incorporating key components of the patient’s history. A template used by our clinical liaisons ensures that key information is identified and recorded. Ongoing systematic education and discussions with medical directors ensures understanding, accurate interpretation, and meaningful incorporation of this information into IRF admission decisions.

As noted above, patient with active cancer being evaluated for admission with a KPS of 40 or less has a near 60% ACT rate [7]. For such patients, the teams default setting should be to deny admission unless there are extenuating factors in the patient’s history that make them likely to become a successful admission. This assessment should be essentially agnostic to the cause of the admission in patients with advanced cancer. The patient was doing well (i.e., living at home independently) until the event that resulted in profound functional loss (i.e., an intracerebral hemorrhage and pneumonia) does not negate the fact that medical intervention was required to prevent the patient from dying. The team should question what meaningful interventions remain available to prevent the patient from dying when another major even occurs—and if they are sufficient with respect to efficacy and prolongation of life—to allow the patient to benefit from IRF admission. Phrased another way, many of the patients we consider for IRF admission nearly died because of their advanced cancer or its treatment. What interventions do we have to keep it from happening again? If the answer is “none,” then we should not admit the patient except under very specific conditions and for very truncated goals.

Admission Pathways

Because of the complexities inherent in admitting patients with active cancer to IRF, we have developed and refined conceptual pathways (restorative, supportive, and transitional) to help guide and inform admission decisions and treatment planning.

Restorative Pathway

The restorative pathway is for patients with good oncologic prognosis and functional deficits that otherwise make them good candidates for IRF. Their goals for admission are similar to most other patients admitted to IRF. Restorative pathway patients are deemed low risk for ACT and death and can benefit from standard rehabilitation interventions and lengths of stay with the goal of returning them to the highest possible level of function and quality of life thereby supporting a safe discharge home.

Supportive Pathway

For patients with functional deficits and no meaningful treatment options, considerations for IRF admission are much more complicated. Patients in the last few days or weeks of life may benefit from a very truncated (i.e., 5 day) admission to train them and their caregivers and provide the equipment they need to return home with hospice. Such training can allow them to live as functionally and comfortably as possible—at home with their loved ones—for the time they have left. Critically, the supportive pathway is predicated on the patient and their family/caregivers knowing and fully accepting that the patient is dying eminently. They must understand and agree with the limited goals for admission. Conflict occurs when a dying patient’s and family’s expectations exceed what is possible from an IRF admission. Patients with severe functional deficits, progressive cancer without meaningful treatment options, and unrealistic expectations should not be admitted to IRF.

Transitional Pathway

The transitional pathway is only to be used when the patient’s status is not clear. It should not be used because the team failed to get information that would inform their decision. It should only be used when information is not knowable. For instance, an extremely ill patient with newly diagnosed metastatic melanoma may respond well to new therapies. If such a patient otherwise meets criteria for admission, then they should be considered a reasonable candidate. They are transitional because their response, thought likely to be good, is not knowable. If they respond well, then their stay in IRF can be extended. If they do not, then the team should be quick to transition to a hospice discharge. This is in contradiction to patient with end-stage metastatic melanoma who has already tried and failed all available treatment options. If such a patient is considered for a new line of therapy that is not likely to be efficacious, they should only be admitted on the supportive pathway.

Education and Communication

It goes without saying that the field of oncology is both vast and complex. The fund of knowledge required to make good oncologic and rehabilitation decisions far exceeds that of most clinicians. Though daunting, we have found that regular, ongoing, and case-based education can be very effective in providing the clinicians, including physicians, therapist, nurses, and clinical liaisons, with the knowledge they need to support good decision-making—and rehabilitative care—with respect to IRF admission of cancer patients.

By far, the most effective and popular educational offering at our institutions are monthly Cancer Team Rounds. Following the Oncology Tumor Board model, Cancer Team Rounds enlists treating clinicians including physical medicine and rehabilitation physicians, physical therapist, occupational therapists, speech language pathologists, nurses, clinical liaisons, social workers, and trainees. The treating team enters the information of selected patients into a templated PowerPoint slide deck, thus ensuring consideration and documentation of key elements of the oncologic history as discussed above. If information is not available, the treating team is encouraged to obtain the information or acknowledge why they were unable to obtain it. The patient’s assigned rehabilitation track is listed as their rehabilitation plan of care across all treating disciplines. The preceptor (usually the author) will add didactic teaching slides to supplement learning of oncology principles and practice. During the 45-min virtual presentation/discussion covering two to three patients, the oncologic and medical history, appropriateness for IRF admission, inpatient rehabilitation progress, and plan for outpatient rehabilitative follow-up (if appropriate) are discussed in detail.

In addition to education, the cancer rehabilitation team from all disciplines (liaison, therapists, attending physiatrist, etc.) and phases of the process from initial screening by a clinical liaison to discharge are systematically encouraged to communicate with each other and outside clinicians. Best practices mandate a cancer team huddle within 48–72 h of admission on each cancer patient at which time the oncologic and medical history are reviewed. Patients at highest risk for ACT are placed on a high-risk protocol, a pathway is assigned, and a tentative plan for discharge is created. The attending physician is encouraged to contact the patient’s oncologist and/or surgeon to fill in any knowledge gaps concerning their history and oncologic plan of care. While the oncology clinician is unlikely to answer questions such as “What is the patient’s prognosis,” they may answer more specific questions like “Do you expect the patient to have a good response to chemotherapy?” A list of questions likely to elicit the critical information supporting our internal determination of prognosis is available to the rehabilitation team.

Conclusions

The art and science of determining the prognosis of patients under consideration for IRF is one of the most challenging aspects of inpatient rehabilitation. Though daunting, education, communication, and experience coupled with meticulous attention to eliciting a comprehensive oncologic history can significantly improve decision-making. The goal is not to exclude all patients who are actively dying from IRF but to ensure they are recognized as such. It is not compassionate to subject a dying patient with unrealistic expectations to the rigors of inpatient rehabilitation—such a patient’s needs are better met in the hospice setting. Similarly, it is not compassionate to expect the rehabilitation team to provide futile care in pursuit of unrealistic goals.

References

Huang ME, Sliwa JA. Inpatient rehabilitation of patients with cancer: efficacy and treatment considerations. PM&R. 2011;3(8):746–57.

Gallegos-Kearin V, Knowlton SE, Goldstein R, Mix J, Zafonte R, Kwan M, et al. Outcome trends of adult cancer patients receiving inpatient rehabilitation: a 13-year review. Am J Phys Med Rehab. 2018;97(7):514–22.

Shin KY, Guo Y, Konzen B, Fu J, Yadav R, Bruera E. Inpatient cancer rehabilitation: the experience of a national comprehensive cancer center. Am J Phys Med Rehab. 2011;90(5):S63–8.

Reilly JM, Ruppert LM. Post-acute care needs and benefits of inpatient rehabilitation care for the oncology patient. Curr Oncol Rep. 2023;25(3):155–62.

Marciniak CM, Sliwa JA, Spill G, Heinemann AW, Semik PE. Functional outcome following rehabilitation of the cancer patient. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 1996;77(1):54–7.

McNair KM, Zeitlin D, Slivka AM, Lequerica AH, Stubblefield MD. Translation of Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) for use in inpatient cancer rehabilitation. PM R. 2023;15(1):65–8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34837660/.

McNair K, Botticello A, Stubblefield MD. Using performance status to identify risk of acute care transfer in inpatient cancer rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2024;S0003-9993(24)00033-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38232794/.

Tennison JM, Sullivan CM, Fricke BC, Bruera E. Analysis of adherence to acute inpatient rehabilitation in patients with cancer. J Cancer. 2021;12(20):5987.

Tennison JM, Fricke BC, Fu JB, Patel TA, Chen M, Bruera E. Medical complications and prognostic factors for medically unstable conditions during acute inpatient cancer rehabilitation. JCO oncology practice. 2021;17(10):e1502–11.

Tennison JM, Asher A, Hui D, Javle M, Bassett RL, Bruera E. Palliative rehabilitation in acute inpatient rehabilitation: prognostic factors and functional outcomes in patients with cancer. The Oncologist. 2023;28(2):180–6. Identifies prognostic factors and functional outcomes for cancer patients in the IRF setting

Parajuli J, Hupcey JE. A systematic review on barriers to palliative care in oncology. Am J Hosp Palliat Med®. 2021;38(11):1361–77.

Hagerty RG, Butow PN, Ellis PM, Lobb EA, Pendlebury SC, Leighl N, et al. Communicating with realism and hope: incurable cancer patients’ views on the disclosure of prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(6):1278–88.

Enzinger AC, Zhang B, Schrag D, Prigerson HG. Outcomes of prognostic disclosure: associations with prognostic understanding, distress, and relationship with physician among patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(32):3809.

Christakis NA, Smith JL, Parkes CM, Lamont EB. Extent and determinants of error in doctors’ prognoses in terminally ill patients: prospective cohort studyCommentary: Why do doctors overestimate? Commentary: Prognoses should be based on proved indices not intuition. BMJ. 2000;320(7233):469–73.

Lamont EB, Christakis NA. Prognostic disclosure to patients with cancer near the end of life. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(12):1096–105.

Evans C, McCarthy M. Prognostic uncertainty in terminal care: can the Karnofsky index help? Lancet. 1985;1(8439):1204–6.

Forster LE, Lynn J. Predicting life span for applicants to: inpatient hospice. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148(12):2540–3.

Maltoni M, Nanni O, Derni S, Innocenti M, Fabbri L, Riva N, et al. Clinical prediction of survival is more accurate than the Karnofsky performance status in estimating life span of terminally ill cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30(6):764–6.

Glare P, Virik K, Jones M, Hudson M, Eychmuller S, Simes J, et al. A systematic review of physicians’ survival predictions in terminally ill cancer patients. BMJ. 2003;327(7408):195–8.

Chow E, Davis L, Panzarella T, Hayter C, Szumacher E, Loblaw A, et al. Accuracy of survival prediction by palliative radiation oncologists. Int J Radiat Oncol* Biol* Phys. 2005;61(3):870–3.

Gripp S, Moeller S, Bölke E, Schmitt G, Matuschek C, Asgari S, et al. Survival prediction in terminally ill cancer patients by clinical estimates, laboratory tests, and self-rated anxiety and depression. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(22):3313–20.

Twomey F, O’Leary N, O’Brien T. Prediction of patient survival by healthcare professionals in a specialist palliative care inpatient unit: a prospective study. Am J Hosp Palliat Med®. 2008;25(2):139–45.

Amano K, Maeda I, Shimoyama S, Shinjo T, Shirayama H, Yamada T, et al. The accuracy of physicians’ clinical predictions of survival in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50(2):139-46. e1.

Perez-Cruz PE, Dos Santos R, Silva TB, Crovador CS, de Angelis Nascimento MS, Hall S, et al. Longitudinal temporal and probabilistic prediction of survival in a cohort of patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48(5):875–82.

Fairchild A, Debenham B, Danielson B, Huang F, Ghosh S. Comparative multidisciplinary prediction of survival in patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:611–7.

Barnes EA, Chow E, Tsao MN, Bradley NM, Doyle M, Li K, et al. Physician expectations of treatment outcomes for patients with brain metastases referred for whole brain radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol* Biol* Phys. 2010;76(1):187–92.

Faris M. Clinical estimation of survival and impact of other prognostic factors on terminally ill cancer patients in Oman. Support Care Cancer. 2003;11:30–4.

Feinstein AR. Symptoms as an index of biological behaviour and prognosis in human cancer. Nature. 1966;209(5020):241–5.

Viganò A, Dorgan M, Buckingham J, Bruera E, Suarez-Almazor ME. Survival prediction in terminal cancer patients: a systematic review of the medical literature. Palliat Med. 2000;14(5):363–74.

Moroni M, Zocchi D, Bolognesi D, Abernethy A, Rondelli R, Savorani G, et al. The ‘surprise’question in advanced cancer patients: a prospective study among general practitioners. Palliat Med. 2014;28(7):959–64.

Moss AH, Lunney JR, Culp S, Auber M, Kurian S, Rogers J, et al. Prognostic significance of the “surprise” question in cancer patients. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(7):837–40.

Owusuaa C, Dijkland SA, Nieboer D, van der Heide A, van der Rijt CC. Predictors of mortality in patients with advanced cancer—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers. 2022;14(2):328.

Stubblefield MD, Tortorella B, Alfano CM. Embracing complexity-the role of cancer rehabilitation in restoring and maintaining function and quality of life in cancer survivors with radiation fibrosis syndrome. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep. 2023;1–4. Discusses the importance of cancer rehabilitation clinicians understanding and owning the complexity of cancer survivors

West HJ, Jin JO. Performance status in patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(7):998.

Jang RW, Caraiscos VB, Swami N, Banerjee S, Mak E, Kaya E, et al. Simple prognostic model for patients with advanced cancer based on performance status. Journal of oncology practice. 2014;10(5):e335-e41. Demonstrates the critical importance of performance status in predicting prognosis in patients with advanced cancer

Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. New Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–42.

Padgett LS, Asher A, Cheville A. The intersection of rehabilitation and palliative care: patients with advanced cancer in the inpatient rehabilitation setting. Rehabilit Nurs J. 2018;43(4):219–28.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Michael Stubblefield wrote all sections of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stubblefield, M.D. The Art and Science of Predicting Prognosis in Cancer Rehabilitation. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40141-024-00446-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40141-024-00446-6