Abstract

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic, inflammatory, immune-mediated disease. This study assessed the time at which patients switched from a conventional oral systemic treatment to a biologic therapy; patient clinical and quality of life (QoL) outcomes associated with oral systemic treatments; and the proportion of patients who persisted on oral therapy (nonswitchers), despite reported suboptimal clinical and QoL outcomes.

Methods

This data analysis used the Adelphi Real World Psoriasis Disease Specific Programme, a non-interventional, retrospective, cross-sectional survey conducted in the USA, France, Germany, and United Kingdom (August 2018–April 2019). Kaplan–Meier (KM) analysis assessed switching from oral to biologic therapy in patients treated ≥ 3 years at survey completion (n = 597). The severity of psoriasis was reported by physicians as the percentage of body surface area (BSA) affected by psoriasis. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) scores were calculated for three groups: nonswitchers who met treatment failure criteria, nonswitchers who did not meet failure criteria, and switchers to a biologic therapy.

Results

In KM analysis, approximately 50% of the patient population switched by 24 months. A substantial portion of nonswitchers continued to have moderate-to-severe psoriasis. Among nonswitchers, 57–77% had BSA ≥ 3% and 16–24% had BSA ≥ 10% at the time of the survey compared with 37% of switchers who had BSA of ≥ 3% and 9% who had BSA of ≥ 10%. QoL was poor among nonswitchers. The mean [standard deviation (SD)] DLQI scores for nonswitchers meeting treatment failure criteria, nonswitchers not meeting failure criteria, and switchers were 6.11 (4.55), 2.62 (3.29), and 2.25 (4.23), respectively.

Conclusion

There is a clear unmet need for more effective oral therapies, and further research into the reasons for patients remaining undertreated, which may include patient preference for oral treatments (despite lack of response), contraindications, or insurance/formulary-related barriers to access, are needed.

Graphical Abstract

Plain Language Summary

Psoriasis is a common skin disease that causes itchy, painful, scaly sores. Patients may feel stigmatized, which can impact their quality of life and productivity. About 1 in 5 patients have severe psoriasis, which is harder to treat and may require pills or shots. Both shots and pills are effective at treating psoriasis; however, many patients choose to continue taking pills, even if their psoriasis worsens, for reasons including a desire to avoid needles. We described patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis who started on pills and either remained on pills or switched to shots by the time of the survey. We looked at the reasons they gave for switching, as well as at quality of life measures reported by the patients. To do this, we analyzed data from a survey called the Adelphi Real World Psoriasis Disease Specific Programme. This survey was conducted among doctors who treat skin diseases and their patients. Participating doctors and patients from the USA, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom were asked questions about the patients’ health and how psoriasis affects their lives. Survey results showed that nearly half of patients switched to shots by 24 months, and most who switched cited treatment failure as the reason. Those who continued to take their pills despite having more severe psoriasis symptoms had more itching and pain and had lower quality of life than those who switched to shots. This suggests that there is a need for more effective oral treatments for patients with psoriasis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Psoriasis, a chronic, inflammatory, immune-mediated disease, is treated with systemic conventional oral therapies or injectable biologic treatments. |

A recent survey of patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis showed that a substantial proportion remain untreated or undertreated. |

This retrospective analysis of an international, cross-sectional survey assessed switching from an oral to biologic therapy, and the proportion of patients who remained on oral therapy despite suboptimal outcomes assessed by clinical and quality of life measures. |

Approximately 50% of patients receiving oral therapies switched to biologics by 24 months, primarily because of reported treatment failure, and a substantial proportion of those who did not switch continued to experience moderate-to-severe symptoms and reduced quality of life. |

There is a clear unmet need for more effective oral therapies for moderate-to-severe psoriasis. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a graphical abstract to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22634095.

Introduction

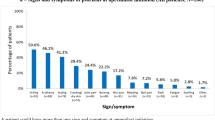

Psoriasis is a common chronic, inflammatory, immune-mediated disease characterized by red plaques with silvery scales that mostly often appear on the scalp, elbows, and knees, although other areas of the skin may be affected [1]. On the basis of estimates from different countries, psoriasis is a serious global health problem, with a worldwide prevalence between 0.09% and 11.43%, or approximately 100 million individuals [2]. Severity of psoriasis is often defined by the percentage of body surface area (BSA) involved. However, despite BSA severity, psoriasis may have a serious emotional impact on patients if it occurs in locations such as the face, hands, feet, scalp, or genitals [1]. The most bothersome symptoms reported by patients are itching, flaking, pain, and a burning sensation [3]. Emotional and social impacts are also frequently reported by patients, including avoidance of social interactions, meeting new people, having personal relationships, and avoiding certain activities [3]. Work productivity of patients with psoriasis also may be affected. A National Psoriasis Foundation survey [4] found that, after adjusting for age and sex, patients with severe psoriasis were 1.8 times more likely to be unemployed compared with those with mild psoriasis. Among those who were employed, almost half (49%) of full-time employees reported missing work because of their psoriasis. Among the 12% who were not employed, 92% cited their psoriasis as the sole reason for not working [4]. Psoriasis therefore impacts the physical, social, emotional, and economic aspects of daily living.

Available treatment options for psoriasis are classified as nonsystemic (topical modalities and phototherapy) and systemic [5]. Nonsystemic topical agents include corticosteroids, vitamin D analogs, calcineurin inhibitors, coal tar derivatives, anthralin, and retinoids [5]. Systemic conventional oral therapies such as methotrexate, cyclosporine, and acitretin have known organ toxicity, thus their use is limited and monitored closely [6]. Approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2014, apremilast is an oral phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE-4) inhibitor for treatment of patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis for whom systemic therapy is appropriate, offering physicians an alternative oral option.

The US and European S3 guidelines recommend biologic therapies, i.e., tumor necrosis factor inhibitors adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab, as second- or third-line therapies for treating moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis [1, 7]. Newer biologic treatments, such as risankizumab, guselkumab, secukinumab, ixekizumab, and brodalumab, offer superior efficacy compared with placebo, resulting in complete or almost complete skin clearance compared with antitumor necrosis factor therapy [8]. However, their use is limited owing to factors such as the fear of injections, potential adverse events (AEs), high treatment costs, and insurance- and/or formulary-related barriers to access [9]. In a 2020 survey of patients who self-reported moderate-to-severe psoriasis (psoriasis BSA that could be covered by ≥ 4 palms), 29–30% of patients were receiving biologic therapy and 12–16% of patients were not receiving any treatment for their psoriasis [10]. Therefore, many patients who are eligible for systemic therapy remain untreated or undertreated.

The present retrospective analysis of data from a multinational cross-sectional physician and patient survey was designed to assess the likelihood and the time to switch from conventional oral systemic treatments to biologic therapy, to evaluate patient clinical and quality of life (QoL) outcomes, and to determine the proportion of patients who remained on oral therapy, despite suboptimal clinical and QoL outcomes.

Methods

This retrospective data analysis used data from the Adelphi Real World Psoriasis Disease Specific Programme (DSP), a non-interventional, cross-sectional survey. The survey was administered in the USA between August and November 2018, and in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom between March and April 2019. The survey captured current (at the time of the survey) and historical patient data from both dermatologists and their patients via physician and patient surveys. Physicians also retrospectively reported patient and treatment details from records (physician-completed patient record forms). The survey collected historical data, such as percentage BSA at diagnosis, current BSA, first oral treatment prescribed, current systemic oral and biologic use, and current patient-reported QoL outcomes. The full DSP survey methodology is published [11]. To summarize, dermatologists who treat patients with active psoriasis completed a Patient Record Form (PRF) for ten of their patients with psoriasis, seven of whom were randomly selected. A further three patients were selected on the basis of current treatment with guselkumab (two patients) or ixekizumab (one patient) at the time of survey administration. This additional treatment-specific sampling criterion was enacted by the Adelphi DSP survey to ensure a sufficient sample size for analysis of patients receiving prespecified biologic therapies. The patients whose information was recorded in a PRF were invited to complete a patient self-completion form, independent of their dermatologist and immediately following their visit. Completion was voluntary; thus, data reported by patients represented a self-selected sample.

Dermatologists were eligible to participate in the psoriasis DSP if they were actively involved in the management of psoriasis and saw ≥ 10 patients with psoriasis in a typical month. Patients were included if they were aged ≥ 18 years, had a confirmed diagnosis of psoriasis, and had started taking a systemic oral treatment (Fig. 1). Patients were excluded from the current analysis if they were missing a treatment history. Patients were excluded if they were on their current treatment for < 3 months at the time of data collection. This latter exclusion criterion was designed to capture the treatment experience of patients who were consistent users of systemic therapies and exclude those who were still in the introductory phase of their current treatment at the time of survey completion. All patients (including those who switched before 3 months) were included in the Kaplan–Meier analyses, since the focus was on the time it took to switch. Participating dermatologists completed detailed patient records, which included information about patients’ current BSA affected by psoriasis, BSA at time of diagnosis, and current and prior oral and/or biologic therapies. Patient treatment patterns (switched to a biologic therapy versus nonswitchers who remained on oral therapy) and treatment outcomes were recreated by combining the physician- and patient-provided data (Fig. 1). In nonswitchers, oral treatment failure was examined and defined as meeting any of the following criteria: (1) condition not improved or worsened since oral initiation, as determined by the physician, (2) lack of psoriasis control or loss of efficacy over time (current percentage BSA greater than the mean percentage BSA of switchers to biologic therapy at the time of switching, which was 3.5%), and (3) physician- or patient-reported dissatisfaction with psoriasis control.

Study design schematic. *Note: The psoriasis survey was conducted in the USA between August and November 2018 and in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom between March and April 2019. †At the time of survey. BSA body surface area; DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index; PsO psoriasis; QoL quality of life; WPAI work productivity and activity impairment

Outcome Measures

The primary objective, time to switch from an oral treatment to a biologic therapy, was assessed through KM analysis using the dates of oral therapy initiation and switching to biologics from the patient record. The duration of time to switch was derived from the initiation of the oral therapy until a switch to a biologic treatment occurred. Clinical and patient-reported outcome measures were assessed for patients who remained on their current treatment for ≥ 3 months. Clinical outcomes included disease severity, as measured by the percentage BSA affected by psoriasis and categorized as follows: mild to moderate < 3%, moderate to severe 3–10%, severe > 10%. The affected BSA was also an indicator for treatment effectiveness and disease control. Patient-reported outcomes were collected using several measures. The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) is a validated, 10-question, QoL questionnaire that covered six domains: symptoms and feelings, daily activities, leisure, work and school, personal relationships, and treatment. Four levels of response categories included “not at all,” “a little,” “a lot,” and “very much,” with scores ranging from 0 to 30; higher scores indicated greater impairment of QoL [12]. In the European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 3 Level Version (EQ-5D-3L), patients reported severity levels of 5 dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression) on a 3-point scale, converted to a score of 1 (best possible health) to 0 (worst possible health) [13]. The Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire measured impairment leading to reduced work productivity and effectiveness, absenteeism, and activity impairment on a scale ranging from 0% to 100%, where higher scores indicated increased impairment [14]. Last, patient responses to QoL questions were used to assess the patients’ perspectives.

Statistical Analysis

Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to determine the time on oral therapy, or time to switch from an oral to a biologic therapy. The percentages of patients switching at both 12 and 24 months were estimated overall and by oral medication, country, and affected BSA at time of diagnosis. Additionally, hazard ratios (HRs) for relative rate of treatment switching at 12 months and 24 months were estimated using a Cox regression model, with Breslow method used for ties to compare strata by first oral treatment (methotrexate, apremilast, and other orals), country (Germany, United Kingdom, and USA compared with the reference data from France), and baseline severity (mild, moderate, and severe). All eligible patients who started oral systemic therapy were assessed in all KM analyses.

Affected BSA was reported at the time of survey completion for nonswitchers and for switchers to biologic therapies. For reference, percentage BSA was also reported retrospectively at time of diagnosis of psoriasis and at initiation of current treatment for nonswitchers and switchers. Subsequent analyses focused on patients who remained on their current therapy for at least 3 months and were divided into three groups: nonswitchers who met treatment failure criteria, nonswitchers who did not meet failure criteria, and switchers to a biologic therapy. Patient characteristics were described for patients in each group. Continuous outcomes were reported as medians [interquartile range (IQR)], and means were compared using analysis of variance. Categorical outcomes were presented as absolute (n) and relative frequencies (%), and ordered categorical variables were compared using chi-squared and Kruskal–Wallis tests. Fisher’s exact and t-tests were used to compare characteristics between groups. Finally, mean current DLQI, EQ-5D-3L, and WPAI scores were calculated for the three groups previously described.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study used data from the Adelphi Real World Psoriasis Disease Specific Programme (DSP). Access to the database was granted by Adelphi under license. No patients were directly involved in the study, and only deidentified patient information was used; thus, institutional review board approval was waived. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

From 2018 to 2019, the Psoriasis DSP surveyed 80 dermatologists in the USA, 50 in France, 50 in Germany, and 42 in the United Kingdom. In total, 597 patients who initiated systemic oral therapy were included in the KM analyses; 345 were being treated with oral therapies at the time of survey completion, and 252 had switched from a conventional oral systemic treatment to a biologic therapy. After excluding patients who were on their current treatments for < 3 months and those who could not be classified as meeting or not meeting failure criteria, 434 patients were included in all other analyses. Of these patients, 92 were classified as nonswitchers who met treatment failure criteria, 179 as nonswitchers not meeting failure criteria, and 163 as switchers to a biologic therapy (Fig. 2). The median (IQR) age of patients included in the analysis was 44 (35.0–55.0) years, and 57.6% of the sample was male (see demographics and baseline patient characteristics, Table S1). At the time of the survey, the most prescribed oral treatment was methotrexate (31.8%), followed by apremilast (16.8%). Nonswitchers who met treatment failure criteria had a median BMI of 27.2 kg/mg2, compared with 24.8 kg/mg2 for nonswitchers who did not meet failure criteria and 26.0 kg/mg2 for switchers to a biologic therapy. Time since diagnosis with psoriasis was 112.6 months for switchers, 76.3 months for nonswitchers who did not meet failure criteria, and 56.1 months for nonswitchers who met treatment failure criteria; duration of current treatment since initiation of oral therapy was 24.8 months for switchers, 12.0 months for nonswitchers who did not meet failure criteria, and 11.7 months for nonswitchers who met treatment failure criteria (Table 1).

The KM curve for the overall time to switch from an oral to a biologic therapy up to 24 months is shown in Fig. 3. The rate of switching was higher in the first 12 months from initiation of oral therapy. Approximately 50% of the patient population examined had switched treatments by 24 months. Among patients who switched, treatment failure was the most commonly reported reason (85%); the remaining 15% reported reasons such as condition improvement, lack of tolerability/side effects, test/lab results required treatment switch, or patient request for monotherapy or a therapy with a different mode of action. The KM curve for the time to switch, stratified by country, showed that Germany had the lowest rate of switching compared with the other three participating countries (Fig. 4). The KM curve for the time to treatment switch, stratified by the type of first oral therapy, showed that patients on fumarate had the lowest proportion of switching, followed by acitretin (Fig. 5). In descriptive analyses, methotrexate was the most used first oral treatment (20.0% overall), followed by apremilast (14.8% overall). The USA had the highest proportion of patients using apremilast (29.9%), with Germany having the highest proportion of patients using fumarate and the United Kingdom having the highest proportion of patients on acitretin (Table 1).

The overall 12 month rate for switching from an oral therapy was estimated to be 37%, increasing to an estimated 51% at 24 months. The highest proportion of switching was among methotrexate users at 12 months (42%) and apremilast users at 24 months (73%). By country, the proportion switching at 12 months was highest for patients in France (44%); the proportion switching at 24 months was highest for patients in the USA (69%). Patients with < 3% affected BSA at diagnosis had a 20% rate of treatment switching at 24 months compared with 51% for patients with 3–10% and > 10% affected BSA (Table 2). Compared with patients receiving methotrexate, those with apremilast as their first oral treatment had a similar rate of switching ([HR 1.33 (95% CI 0.90–1.98]), while those who initiated treatment with other oral therapies had a lower rate of switching (HR 0.58 [95% CI 0.41–0.83]). Compared with patients in France, patients in Germany and the United Kingdom had lower HRs for switching (univariate HR 0.30 [95% CI 0.14–0.64] and HR 0.76 [95% CI 0.44–1.32], respectively). The HR for switching for patients in the USA was similar or slightly greater than that in France (HR 1.18 [95% CI 0.76–1.83]). The rate of switching increased with psoriasis severity. The HR for switching among patients with BSA of 3–10% was 1.57 (95% CI 1.00–2.48), and 2.79 (95% CI 1.76–4.41) among patients with BSA > 10%, compared with patients with a BSA < 3% (Table 2).

Affected BSA at diagnosis and study initiation and current switching patterns are presented in Fig. 6. Among the nonswitchers, 57% who had one oral line of therapy and 77% who had two or more oral lines of therapy had BSA ≥ 3%; 16% and 24%, respectively, had BSA ≥ 10% at the time of the survey. In comparison, 37% of switchers had BSA ≥ 3%, and 9% had BSA ≥ 10%. Compared with the other groups, nonswitchers on second-line therapies had greater proportions of patients with moderate and severe BSA.

The mean (SD) DLQI scores varied across the groups (Fig. 7). Patient-reported QoL was described using mean (SD) DLQI scores for nonswitchers who met treatment failure criteria, nonswitchers who did not meet failure criteria, and switchers (6.11 [4.55], 2.62 [3.29], and 2.25 [4.23], respectively). The proportion of patients reporting itchy or painful skin on the DLQI was lower for switchers (33.3%) compared with nonswitchers who met (91.5%) or did not meet (54.1%) treatment failure criteria. Switchers and nonswitchers who did not meet treatment failure criteria had better mean (SD) EQ-5D-3L scores of 0.93 (0.1) for each group, and WPAI activity impairment scores of 15.3 (17.1) and 15.3 (14.3), respectively, compared with nonswitchers who met treatment failure criteria (EQ-5D-3L, 0.84 [0.2]; WPAI, 24.3 [21.2]; Table 3).

Discussion

Overall, we found that approximately 50% of the participating patients had switched from an oral therapy to a biologic therapy by 24 months, and the rate of switching was higher within the first 12 months. The results of this study largely align with the published literature. Previously reported rates of switching vary in magnitude and methodology, with claims-based database analyses reporting 12-month medication switch rates ranging from 14% [15, 16] to 30% [17] for oral therapies and 7% [15] to 27% [17, 18] for biologics. This study adds treatment switching stratified by the type of oral medication and country to the general knowledge base. We found that patients who used apremilast switched to biologics at a higher rate compared with patients who used other oral therapies. A lower proportion of patients in Germany switched from an oral to a biologic therapy compared with patients in France, the USA, or the United Kingdom, likely due to a high rate of fumarate use in Germany. Differences in treatment guidelines between the countries also may have played a role in the switch rates. Patients with greater psoriasis severity had an increased rate of treatment switching compared with those with mild severity at the time of diagnosis.

Among nonswitchers on second-line therapies, 77% had BSA ≥ 3% and 24% had BSA ≥ 10%, compared with 57% and 16%, respectively, among nonswitchers on first-line therapies. Patients on first-line therapies may have milder forms of psoriasis or may be earlier in their treatment duration and tolerating their treatment well. Psoriasis severity was greater in the nonswitcher groups versus those who switched to a biologic therapy, with 37% of switchers having BSA ≥ 3% and 9% having BSA ≥ 10%. Ragnarson Tennval and colleagues [19] similarly found more moderate-to-severe psoriasis in patients on nonbiologic therapies versus biologic therapies. The high proportion of patients on suboptimal treatment or those potentially undertreated for psoriasis, as observed in this study, has also been reported previously in the literature [19, 20]. A US-based claims data analysis of patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis found that one-third of patients were diagnosed but did not receive treatment, and 74% received only topical therapy.

DLQI scores, a measure of patient-reported QoL, were worse for patients classified as nonswitchers who met treatment failure criteria compared with patients who switched to biologic therapy. A patient survey and retrospective chart review of patients in Nordic countries similarly found that QoL and treatment satisfaction were better for patients treated with biologic agents than for those treated with topical or nonbiologic systemic agents [19]. The alignment of clinical and QoL outcomes being worse for nonswitchers versus those who switched may indicate that patients on oral medications may be undertreated, or they may choose to remain on their current treatment despite suboptimal outcomes.

Compared with patients who had methotrexate as their first oral treatment, a greater proportion of patients on other oral systemic therapies switched to a biologic within 2 years of initiation. This suggests a high unmet need. The large affected BSA in patients who persisted on oral therapies and did not switch to a biologic treatment indicates that these patients could be undertreated, or that they have a preference for remaining on an oral therapy despite suboptimal treatment. Further research is warranted to understand the reasons why patients continue to stay on ineffective oral therapies and the clinical and QoL consequences.

A strength of this study is the use of the Adelphi Real World DSP methodology, as it is well validated and provides data reflective of physician and patient perspectives [11, 21, 22]. The DSPs have generated published evidence in more than 80 individual disease areas, including psoriasis [23]. The surveys incorporate multiple stakeholder perspectives offering an overview of the entire patient journey, and the validated and consistent application of its methodology allows for cross-country comparisons over time [23]. However, there are some limitations to the DSP methodology. This was a cross-sectional survey that used retrospective reporting. Thus, the analyses are, at best, descriptive in nature, cannot adequately describe risk, and cannot be used to assess causal associations between current treatments and outcomes. The sample surveyed was not a strictly random sample of patients with psoriasis because dermatologists and patients were included on the basis of the number of patients seen by the dermatologist per month and on the currently prescribed treatments, respectively. Although each physician randomly selected seven patients, the propensity of the patients to visit their physician influenced their chance of being included in the survey and thus this is considered a convenience sample. Patient-reported outcomes were from a self-selected sample, as the surveys were completed voluntarily by patients and may have been impacted by their current condition. A large percentage of the total patient population (62%) did not provide responses to QoL measures. Physician inclusion was likely influenced by their willingness to take part as well as by other practical considerations, depending on the geographic location. Thus, the physician and patient samples may not truly be reflective of the overall physician and patient psoriasis population. Another limitation to note is that the clinical and QoL outcome analyses did not include early discontinuations, as selection was based on treatment duration of ≥ 3 months to focus on the outcomes of patients who were maintained on treatment. Consequently, the rate of treatment switching and categorization of patients in the switchers group may be underestimated. Treatment guidelines differ between countries, and this may have affected the duration of treatment with a specific therapy prior to switching. The impact of country-specific treatment practices may be explored in future research.

In conclusion, patients initiating oral therapies for psoriasis switched to biologic treatments at a high rate, reportedly attributed to treatment failure. Among nonswitchers, a substantial portion continued to experience moderate-to-severe psoriasis and reported poor QoL. There is a clear unmet need for more effective oral therapies, as well as a need for additional research exploring the reasons why patients remain undertreated, such as patient preference for an oral treatment (despite a lack of response), medication contraindications, or insurance- and/or formulary-related barriers to access.

References

Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, Kivelevitch D, Prater EF, Stoff B, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(4):1029–72.

Global Report on Psoriasis. Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2016.

Pariser D, Schenkel B, Carter C, Farahi K, Brown TM, Ellis CN. A multicenter, non-interventional study to evaluate patient-reported experiences of living with psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27(1):19–26.

Armstrong AW, Schupp C, Wu J, Bebo B. Quality of life and work productivity impairment among psoriasis patients: findings from the National Psoriasis Foundation survey data 2003–2011. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12): e52935.

Vangipuram R, Alikhan A. Apremilast for the management of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2017;10(4):349–60.

Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, Feldman SR, Gelfand JM, Gordon KB, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Section 3. Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(4):643–59.

Nast A, Gisondi P, Ormerod AD, Saiag P, Smith C, Spuls PI, et al. European S3-Guidelines on the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris–Update 2015–Short version–EDF in cooperation with EADV and IPC. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(12):2277–94.

Bai F, Li GG, Liu Q, Niu X, Li R, Ma H. Short-term efficacy and safety of IL-17, IL-12/23, and IL-23 inhibitors brodalumab, secukinumab, ixekizumab, ustekinumab, guselkumab, tildrakizumab, and risankizumab for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Immunol Res. 2019;2019:2546161.

Armstrong AW, Robertson AD, Wu J, Schupp C, Lebwohl MG. Undertreatment, treatment trends, and treatment dissatisfaction among patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in the United States: findings from the National Psoriasis Foundation surveys, 2003–2011. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(10):1180–5.

Lebwohl M, Langley RG, Paul C, Puíg L, Reich K, van de Kerkhof P, et al. Evolution of patient perceptions of psoriatic disease: results from the understanding psoriatic disease leveraging insights for treatment (UPLIFT) survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12(1):61–78.

Anderson P, Benford M, Harris N, Karavali M, Piercy J. Real-world physician and patient behaviour across countries: Disease-Specific Programmes—a means to understand. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(11):3063–72.

Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210–6.

EQ-5D-3L User Guide. Basic information on how to use the EQ-5D-3L instrument. EuroQol Research Foundation, 2018. Available at: https://euroqol.org/publications/user-guides/. Accessed: Aug 12, 2022.

Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: General Health V2.0 (WPAI:GH). Reilly Associates Health Outcomes Research, 2004. Available at: http://www.reillyassociates.net/WPAI_GH.html. Accessed: Oct 1, 2020.

Higa S, Devine B, Patel V, Baradaran S, Wang D, Bansal A. Psoriasis treatment patterns: a retrospective claims study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(10):1727–33.

Kaplan DL, Ung BL, Pelletier C, Udeze C, Khilfeh I, Tian M. Switch rates and total cost of care associated with apremilast and biologic therapies in biologic-naive patients with plaque psoriasis. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;12:369–77.

Wu JJ, Pelletier C, Ung B, Tian M. Treatment patterns and healthcare costs among biologic-naive patients initiating apremilast or biologics for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis: results from a US claims analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36(1):169–76.

Wu JJ, Pelletier C, Ung B, Tian M, Khilfeh I, Curtis JR. Real-world switch patterns and healthcare costs in biologic-naive psoriasis patients initiating apremilast or biologics. J Comp Eff Res. 2020;9(11):767–79.

Ragnarson Tennvall G, Hjortsberg C, Bjarnason A, Gniadecki R, Heikkilä H, Jemec GB, et al. Treatment patterns, treatment satisfaction, severity of disease problems, and quality of life in patients with psoriasis in three Nordic countries. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93(4):442–5.

Armstrong AW, Koning JW, Rowse S, Tan H, Mamolo C, Kaur M. Under-treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis in the United States: analysis of medication usage with health plan data. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7(1):97–109.

Babineaux SM, Curtis B, Holbrook T, Milligan G, Piercy J. Evidence for validity of a national physician and patient-reported, cross-sectional survey in China and UK: the Disease Specific Programme. BMJ Open. 2016;6(8): e010352.

Higgins V, Piercy J, Roughley A, Milligan G, Leith A, Siddall J, et al. Trends in medication use in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a long-term view of real-world treatment between 2000 and 2015. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2016;9:371–80.

Disease specific programmes. Adelphi Real World, 2022. Available at: https://adelphirealworld.com/our-approaches/disease-specific-programmes/. Accessed: Apr 12, 2022.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study was sponsored by Bristol Myers Squibb. Funding for the journal’s Rapid Review Service and Open Access Fees were provided by Bristol Myers Squibb.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Medical writing and editorial assistance was provided by Nicole Boyer, PhD, MPH, of Peloton Advantage, LLC, an OPEN Health company, and funded by Bristol Myers Squibb.

Author Contributions

Sydney Thai, Yichen Zhong, and Joe Zhuo provided substantial contributions to the study design. Sophie Barlow participated in data acquisition and data analysis. Sydney Thai, Sophie Barlow, James Lucas, James Piercy, Yichen Zhong, Joe Zhuo, and Jashin J Wu participated in data interpretation. All authors had full access to the data and contributed to the drafting, critical review, and revision of the manuscript, with the support of a medical writer provided by Bristol Myers Squibb. All authors granted approval of the final manuscript for submission. The authors thank the patients who participated in the survey for this study and acknowledge James Hetherington, BSc (Hons), of Adelphi Real World for his contributions to this analysis.

Disclosures

Sydney Thai was completing a pre-doctoral fellowship with Bristol Myers Squibb at the time of this study and is currently at the Gillings School of Global Public Health of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Yichen Zhong and Joe Zhuo are employees of Bristol Myers Squibb and may own stock/options in the company. Sophie Barlow, James Lucas, and James Piercy are employees of Adelphi Real World, which provided the data used in this analysis. Jashin J. Wu is or has been an investigator, consultant, or speaker for AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Arcutis Biotherapeutics, Aristea Therapeutics, Bausch Health, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Dermavant Sciences, DermTech, Dr. Reddy's Laboratories, Eli Lilly, EPI Health, Galderma, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Mindera Health, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Samsung Bioepis, Sanofi Genzyme, Solius, Sun Pharmaceutical, UCB, and Zerigo Health.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study used data from the Adelphi Real World Psoriasis Disease Specific Programme (DSP). Access to the database was granted by Adelphi under license. No patients were directly involved in the study, and only de-identified patient information was used; thus, institutional review board approval was waived. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Availability

All data, ie, methodology, materials, data, and data analyses, that support the findings of this survey are the intellectual property of Adelphi Real World. All requests for access should be addressed directly to James Lucas at james.lucas@adelphigroup.com.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thai, S., Barlow, S., Lucas, J. et al. Suboptimal Clinical and Quality of Life Outcomes in Patients with Psoriasis Undertreated with Oral Therapies: International Physician and Patient Survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 13, 1289–1303 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-00927-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-00927-x