Abstract

Introduction

Psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory disease characterised by pruritic skin lesions that impair quality of life (QOL). Long-Term Documentation of the Utilization of Apremilast in Patients with Plaque Psoriasis under Routine Conditions (LAPIS-PSO; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02626793) was a 52-week, prospective, multicentre, observational cohort study conducted in real-world dermatology clinical settings in Germany. We evaluated physician- and patient-reported outcomes for QOL, effectiveness and tolerability in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis vulgaris in LAPIS-PSO.

Methods

The primary endpoint was the percentage of patients achieving Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) score ≤ 5 or ≥ 5-point improvement from baseline in DLQI score at visit 2 (~ 4 months after baseline). Secondary endpoints included assessments of symptoms and disease severity. Tolerability was evaluated based on adverse events (AEs). A pre-defined subgroup analysis based on baseline Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA) score (2 or 3 versus 4) was performed. Data were examined descriptively through visit 5 (~ 13 months) using the last-observation-carried-forward (LOCF) approach and data as observed.

Results

In total, 257 patients were included for efficacy assessment. On LOCF analysis, most patients achieved the primary endpoint at visit 2 (66.5%); DLQI response was maintained at visit 5 (72.4%). Earlier treatment response was observed in patients with a PGA score of 2 or 3 versus 4 (visit 1 PASI ≤ 3: 20.5% versus 10.8%). Adverse events were consistent with the known safety profile of apremilast.

Conclusions

In routine clinical care in Germany, patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis benefited from apremilast treatment up to ~ 13 months, consistent with findings from clinical trials, with a good safety profile.

Similar content being viewed by others

Why carry out this study? |

The burden of psoriasis, which often affects visible and sensitive special areas (e.g., scalp, palmoplantar areas, nails), may not be fully captured by traditional measures of disease severity, and many patients with moderate disease are undertreated |

Apremilast is an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor that has demonstrated efficacy and tolerability in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in clinical trials, including improvements in quality of life and efficacy for psoriasis in special areas; however, less is known about effectiveness and quality-of-life outcomes with apremilast in clinical practice |

What did the study ask? |

The Long-Term Documentation of the Utilization of Apremilast in Patients with Plaque Psoriasis under Routine Conditions (LAPIS-PSO; NCT02626793), conducted in dermatology clinical settings in Germany, evaluated the real-world effectiveness and tolerability of apremilast treatment, including assessments of patient-reported outcomes |

What was learned from the study? |

In LAPIS-PSO, apremilast treatment was well tolerated and demonstrated sustained improvements in quality of life, psoriasis in special areas, symptoms (itch and pain) and overall disease severity up to ~ 13 months of treatment, including in patients with less severe and more severe psoriasis |

These findings from clinical practice were consistent with results from apremilast clinical trials and confirm that apremilast can benefit patients who have high disease burden due to psoriasis involvement in special areas and bothersome symptoms such as itch and skin pain |

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic, systemic, inflammatory disease characterised by pruritic and painful skin lesions [1,2,3] that often occur in highly sensitive or visible special areas, such as the scalp, palmoplantar areas or nails [4], and can result in physical disability and quality-of-life (QOL) impairments [5,6,7]. Disease burden may not be fully captured by traditional measures of disease severity such as psoriasis-involved body surface area (BSA) or Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) [4, 5], resulting in undertreatment among patients with moderate skin involvement [8]. Consensus guidelines suggest complementing physician-rated assessments with patient-reported outcomes when evaluating treatment effectiveness [5].

Long-term management of moderate to severe psoriasis may involve conventional systemic treatment, biologic therapy or a targeted oral systemic agent such as apremilast [9, 10]. Apremilast is an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor that regulates the inflammatory response in psoriasis by targeting cytokines implicated in psoriasis pathogenesis [11]. Apremilast was approved in Europe in January 2015 for treatment of moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis in adults who failed to respond to, have a contraindication to, or are intolerant to other systemic therapy, including cyclosporine, methotrexate or phototherapy [12]. In placebo-controlled trials, apremilast showed efficacy and tolerability in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, including improvements in QOL and efficacy for psoriasis in special areas [13,14,15,16,17]. Less is known about the effectiveness of apremilast in real-world settings. Patients treated in real-world settings are generally different from those who meet stringent eligibility criteria for phase 3 clinical trials [18]. Studies that evaluate the use of apremilast in routine clinical practice can help inform treatment decisions. A recent European real-world study suggests that, despite its second-line indication, apremilast is often used in patients with more moderate disease than patients included in the pivotal clinical trials [12,13,14, 19]. The Long-Term Documentation of the Utilization of Apremilast in Patients with Plaque Psoriasis under Routine Conditions (LAPIS-PSO; NCT02626793) characterised patients who receive apremilast in real-world dermatology clinical settings in Germany, including assessment of patient-reported outcomes. We report findings of this 52-week, prospective, multicentre, observational cohort study that evaluated effectiveness and safety outcomes in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who received apremilast according to the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC).

Methods

Patient Population

Eligibility was based on the apremilast SmPC; the decision to treat was made by the treating physician prior to and independently of inclusion in the study. Adult patients (≥ 18 years) diagnosed with moderate to severe psoriasis vulgaris were eligible for enrolment. Eligible patients had inadequate response to or intolerance to ≥ 1 prior systemic therapy or contraindication of systemic therapies. Patients previously treated with biologics were excluded.

Study Design

LAPIS-PSO was a prospective, multicentre, observational cohort study conducted in real-world dermatology clinical settings across Germany; physicians with real-world study experience who represented a balanced regional distribution were included. Data collection occurred between August 3, 2015 and June 14, 2018. Study visits were timed according to physicians’ clinical practice, with no strict study visit schedule. To facilitate systematic data analysis, the following time windows for study visits were suggested: optional visit 1, 1 month; visit 2, 4 months; visit 3, 7 months; visit 4, 10 months; visit 5 (end of observation), 13 months (Supplementary Fig. 1).

An independent ethics committee (FEKI; Freiburger Ethikkommission International, reference 015/1385) approved the study protocol, and all patients provided written, informed consent before participating. Local ethics committees approved the protocol for participating study sites (UK RUB Ruhruniversität Bochum, reference 52/2015; Sächsische Landesärztkammer, reference RN EK-BR-74/15-1; Medizinische Fakultät Mannheim, reference 2015-905W-MA; Ethikkommission der Technischen Universität Dresden, reference EK472112015; Medizinische Fakultät der Universität Duisburg-Essen, reference 16-6844-BO). The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was achievement of Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) response (score ≤ 5 or improvement from baseline in DLQI score ≥ 5 points) at visit 2. DLQI response was evaluated at all study visits. Achievement of DLQI score categories [0–1 (no impairment), 2–5 (minimal impairment), 6–10 (moderate impairment), 11–20 (high impairment), 21–30 (highest impairment)] and mean changes from baseline in DLQI score and BSA were also assessed. Other response endpoints [i.e., achievement of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) using a 5-point scale up to 4 (severe)] were: scalp PGA (ScPGA; baseline ScPGA > 0); palmoplantar PGA (PPPGA; baseline PPPGA > 0); and Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI) score in the target (worst) fingernail (tNAPSI; baseline NAPSI > 0). Percentage changes from baseline in pruritus and skin pain visual analogue scale (VAS) scores (0–100 mm; 0 = no pain/itching, 100 = worst pain/itching imaginable) were evaluated at all study visits. Patient satisfaction was assessed at visit 2 using the Patient Therapy Preference Questionnaire (PPQ). Safety was assessed throughout the study on the basis of adverse events (AEs). Physicians recorded all AEs orally mentioned by the patient or noticed by study personnel, starting with the first apremilast dose until ≥ 28 days after the last dose; AEs were recorded within 24 h of the physician becoming aware of the event.

Statistical Analyses

Safety analyses were summarised descriptively in the safety analysis population, which included all patients who received one or more doses of apremilast. Effectiveness and QOL were examined descriptively in the full analysis population, defined as all patients in the safety analysis population with DLQI score > 5 at baseline who had DLQI data available at visit 2. A sample of ~ 500 patients was planned for assessment of the primary endpoint with an accuracy within ± 6 percentage points based on a two-sided 95% confidence interval (CI), assuming 58% of patients having data to analyse for the primary endpoint (i.e. 290 patients) and 60% of patients achieving the primary endpoint. Data were analysed using the last-observation-carried-forward (LOCF) approach to impute missing values and as observed without imputation. To calculate DLQI response rates, missing values were imputed using LOCF for patients who did not attend any study visits but did not drop out early and for patients who dropped out early due to clinical improvement; for patients who dropped out early for another reason, missing values were classified as non-responders.

In the pre-specified subgroup analysis by baseline Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA) category (PGA = 2 or 3 versus PGA = 4), achievement of DLQI response and mean BSA and PASI were assessed at all study visits. Achievement of PASI ≤ 3 by baseline PGA category was assessed at all study visits.

Results

Patients

A total of 391 patients at 75 sites were enrolled; 364 patients met inclusion criteria for the safety population, and 257 patients were evaluated for efficacy in the full analysis population (Supplementary Fig. 2). Among 179 patients in the safety analysis population who discontinued early, common reasons for discontinuation were lack of efficacy [n/N = 97/391 (24.8%)] and AEs [n/N = 41/391 (10.5%)] (Supplementary Fig. 2). The majority of patients who discontinued treatment [81.2% (95/117)] started a new psoriasis therapy, and 18.8% (22/117) terminated their therapy fully.

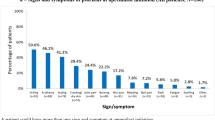

Patient demographics and characteristics at baseline were generally similar in the full analysis and safety populations (Table 1, Supplementary Table 1). In the full analysis population, 68.9% (177/257) of patients had a PGA score of 2 or 3 (moderate) and 28.8% (74/257) of patients had a PGA score of 4 (severe); 98.4% (249/253) of patients reported itch as a symptom, scalp psoriasis was present in 80.3% (204/254) of patients, 51.2% of patients had nail involvement (131/256) and 26.5% (66/249) of patients had palmoplantar psoriasis (Table 1). Most patients had prior treatment with topical or systemic therapies. Almost 90% of patients had baseline PGA or Patient’s Global Assessment (PaGA) scores ≥ 3, and many had baseline ScPGA or PPPGA scores ≥ 3 [61.6% (125/203) and 41.8% (28/67), respectively; Table 2]. At baseline and all study visits, the median apremilast dose was 30 mg twice daily, in accordance with the label.

Demographics were generally similar between the PGA severity subgroups and the full analysis population (Table 1). The proportions of patients with psoriasis involvement in the scalp or nails were similar between patients with PGA of 2 or 3 and those with PGA of 4 (scalp: 79.9% and 81.1%; nail: 50.0% and 55.4%); palmoplantar involvement was less prevalent in patients with PGA of 2 or 3 (19.4%) versus PGA of 4 (41.1%) (Table 1). Despite higher PASI among patients with a PGA score of 4, baseline mean DLQI and pruritus VAS scores were generally similar in the two groups (Table 2).

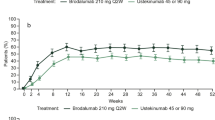

Effects of Apremilast on QOL

In the full analysis population, 66.5% (171/257) of patients achieved the primary endpoint of DLQI response with apremilast treatment (Fig. 1a). More than 50% of patients achieved DLQI response as early as visit 1, and results were generally similar at subsequent study visits (Fig. 1a). The proportions of patients with DLQI improvement of ≥ 5 points increased over time, from 48.2% (124/257) at visit 1 to 66.9% (172/257) at visit 5 (LOCF). Improvements in mean DLQI scores increased with each subsequent study visit (Supplementary Table 2). In the full analysis population, improvements in mean BSA were observed over time with continued apremilast treatment (Supplementary Table 2). Achievement of DLQI scores corresponding to no or minimal QOL impairment (DLQI ≤ 5) increased over time and was reached by 54.5% (140/257) of patients at visit 5 (LOCF) (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Percentage of patients achieving the primary endpoint of DLQI response (DLQI ≤ 5 or DLQI improvement ≥ 5) in a the full analysis population and b by PGA severity subgroup (N = 257). a Data are from the full analysis population. For the as-observed analysis, n/N = number of patients who achieved response/number of patients with available data. b For the as-observed analysis, n/N = number of patients who achieved response/number of patients with available data. BL baseline, DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index, LOCF last observation carried forward, PGA Physician’s Global Assessment, SD standard deviation

Effects of Apremilast on Disease Severity Assessments

In the full analysis population, mean (SD) PASI scores were 7.8 (8.1) at visit 2 and 4.3 (5.2) at visit 5. The proportion of patients achieving PASI responses increased over time. The PASI-50 response rate was 53.9% (96/178) at visit 2 and increased to 80.0% (84/105) at visit 5. The PASI-75 response rate was 27.5% (49/178) at visit 2 and increased to 50.5% (53/105) at visit 5. The PASI-90 response rate was 12.4% (22/178) at visit 2 and increased to 30.5% (32/105) at visit 5.

The proportion of patients with PGA score of 0 was 1.2% (3/256) at baseline and increased to 4.9% (11/226) at visit 2 and 10.0% (13/130) at visit 5.

Subgroup Analysis by Baseline PGA Severity

According to baseline PGA categorisation, DLQI response (LOCF) was achieved by 52.5% (93/177) of patients with a score of 2 or 3 and 59.5% (44/74) of patients with a score of 4 at visit 1. DLQI response rates were similar over time for patients in both PGA severity subgroups, and DLQI improvement was mostly maintained up to visit 5 (Fig. 1b). Continuous improvements in mean BSA and PASI were observed from visit 1 to visit 5 in the full population and in both PGA severity subgroups (Supplementary Fig. 4). Earlier treatment response was observed in patients with a PGA score of 2 or 3, with a greater percentage achieving PASI ≤ 3 as early as visit 1 and at each study visit thereafter compared with patients with severe psoriasis (Fig. 2). Rates of treatment discontinuation were similar in both groups [PGA score of 2 or 3: 48.8% (131/268); PGA score of 4: 50.6% (42/83)].

Percentage of patients achieving PASI ≤ 3 by PGA severity subgroup. Data are from the full analysis population (N = 257). For as-observed analysis, n/N = number of patients who achieved response/number of patients with available data. BL baseline, PASI Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, PGA Physician’s Global Assessment

Effects of Apremilast on Special Areas and Symptoms of Psoriasis

Patients with scalp, palmoplantar and nail psoriasis at baseline demonstrated continuous improvements in clinical assessments at each study visit up to visit 4, which were mostly maintained at visit 5 (Fig. 3). In patients with scalp and palmoplantar involvement at baseline, respectively, the majority of patients achieved ScPGA [54.7% (111/203)] or PPPGA [71.6% (48/67)] score of 0 or 1 at visit 5 (LOCF; Fig. 3a, b). Approximately one-third of patients [35.6% (42/118)] with nail involvement at baseline had tNAPSI score of 0 at visit 5 (LOCF; Fig. 3c).

Percentage of patients achieving a ScPGA score of 0 or 1, b PPPGA score of 0 or 1, or c tNAPSI score of 0 in the full analysis population. aPatients achieving ScPGA or PPPGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) or tNAPSI score of 0. Data are from the full analysis population (N = 257). n/N = number of patients who achieved response/number of patients with available data. BL baseline, PPPGA Palmoplantar Psoriasis Physician’s Global Assessment, ScPGA Scalp Physician’s Global Assessment, NAPSI Nail Psoriasis Severity Index, tNAPSI NAPSI in the target nail

Improvements in pruritus VAS scores exceeding the minimal clinically important difference of > 20% improvement [20] were observed as early as visit 1 and continued over time (Fig. 4a). Similarly, early and sustained improvements in skin pain VAS were observed (Fig. 4b). At visit 5, large improvements were noted in both pruritus and skin pain VAS scores with apremilast treatment (Fig. 4).

At visit 2, many patients strongly agreed that they preferred apremilast [64.3% (133/207)] and considered it to be better tolerated than their prior systemic treatment [59.1% (123/208), data as observed], as evaluated using the PPQ (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Safety and Tolerability

Median apremilast exposure during the study (n = 364) was 0.9 years (329 days), corresponding to 294 patient-years. AEs were reported in 39.8% (145/364) of patients in the safety analysis population; 28.0% (102/364) reported AEs considered to be related to apremilast treatment (Table 3). The majority of treatment-related AEs were mild in severity, and there were few reports of serious treatment-related AEs (Table 3). Less than 9% of patients experienced AEs leading to treatment discontinuation (Table 3).

Four patients reported treatment-related serious AEs, including one serious AE leading to death (completed suicide); the other treatment-related serious AEs were seizure (n = 1), bronchitis (n = 1) and weight loss (n = 1) (Table 3). Relevant medical history and outcomes for patients who had treatment-related serious AEs are provided in Table 3.

One death was reported in a patient who had been diagnosed with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) before starting apremilast. The cause of death reported by the investigator was deterioration/progression of AML. This AE was not considered to be related to apremilast treatment.

In all, 32 patients discontinued treatment due to AEs; AEs occurring in > 1% of patients who discontinued were diarrhoea [1.9% (7/364)] and headache [1.6% (6/364)]. The incidence of treatment-emergent AEs in the LAPIS-PSO study for AEs commonly reported in clinical trials of apremilast (i.e. diarrhoea, nausea, headache and upper respiratory tract infection) are presented in Table 3. For treatment-emergent AEs commonly reported in clinical trials, incidence rates per 100 patient-years were low in LAPIS-PSO, and the median time to first occurrence of these AEs was within the first 2 weeks of treatment (Table 3).

Overall, the incidence rate for depression related to apremilast treatment was 1.7 per 100 patient-years. There were 5/364 patients (1.4%) who reported treatment-related AEs of depression that were moderate in severity. Three patients had a diagnosis of depression at baseline; of these, two patients required treatment for depression. A total of three patients with AEs of depression discontinued apremilast treatment (two of these patients had a prior history of depression), and their depression improved to the level reported at baseline after discontinuing apremilast treatment.

Discussion

In patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis receiving routine clinical care in Germany in LAPIS-PSO, apremilast treatment was well tolerated and had a positive impact on clinical assessments and patient-reported outcomes. Patients achieved early improvement in DLQI and pruritus VAS scores at ~ 1 month, and improvements were maintained with continued apremilast treatment. Sustained improvements on global assessments of disease severity were observed through ~ 13 months of continuous treatment. A high proportion of patients with scalp or palmoplantar psoriasis achieved total or almost complete clearance in these special areas. These real-world findings confirm the effectiveness of apremilast demonstrated in clinical trials [13,14,15,16] and other real-world apremilast studies in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis [21,22,23].

In LAPIS-PSO, the patient population had somewhat lower disease severity at baseline based on mean BSA (21.8%) and PASI (15.1) than patients in the pooled ESTEEM 1 and 2 (24.8%, 18.8%) phase 3 studies of apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Mean pruritus and pain VAS scores were lower at baseline in the current study (56.6 mm, 36.6 mm) compared with the pooled ESTEEM 1 and 2 population (66.6 mm, 58.2 mm). These findings are consistent with other real-world studies that reported use of apremilast in more moderate psoriasis [19, 21, 24] compared with the phase 3 pivotal clinical trials, which enrolled biologic-experienced patients with moderate to severe psoriasis [13, 14]. Despite lower disease severity, mean baseline DLQI score was somewhat higher in LAPIS-PSO (14.1) compared with the pooled population of ESTEEM 1 and 2 (12.7). This observation agrees with other observations that DLQI does not necessarily correlate with disease severity [15] but may correlate with psoriasis involvement in special areas [6]; this finding may also reflect less restrictive eligibility criteria in this real-world study than in the ESTEEM trials, which excluded patients with other clinically significant or major uncontrolled comorbid diseases or infections [13, 14].

Psoriasis involvement in special areas (i.e. sensitive and visible areas), such as the scalp, nails and palmoplantar areas, was prevalent in LAPIS-PSO patients. The proportion of patients with psoriasis involvement in special areas in LAPIS-PSO (i.e. scalp 80%, nail 51% and palmoplantar 27%) was higher than in other prior studies (i.e. scalp 43–52%, nail 23–33% and palmoplantar 14%) [25,26,27] and likely contributed to the high QOL impairment observed in LAPIS-PSO. In addition to QOL improvements, apremilast was associated with early and sustained improvements in the severity of scalp, nail and palmoplantar involvement.

Baseline mean DLQI scores were lower in other real-world studies of apremilast (~ 11.0) [22, 28], possibly due to differences in patient populations. Unlike LAPIS-PSO, other real-world studies did not require patients to be treated as described in the SmPC (e.g. systemic-naive patients were permitted [28] or patients were not required to have moderate to severe psoriasis at baseline [22]). Mean baseline DLQI score in LAPIS-PSO (14.1) was comparable to the recent APPRECIATE real-world study (13.4), a retrospective, non-interventional study that also included patients who initiated apremilast in clinical practice per the SmPC [19].

Achievement of ≥ 5-point improvement in DLQI score at ~ 4 months (when the primary endpoint was assessed) was generally comparable in LAPIS-PSO (61.4%) to the pooled ESTEEM 1 and 2 studies (66.4%); the UNVEIL study (63.8%) of apremilast in patients with moderate plaque psoriasis (BSA 5–10%); and a recent chart review study of patients receiving apremilast for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in clinical practice (63.6%) [15, 22].

Patients in both PGA severity subgroups in LAPIS-PSO had similar rates of ≥ 5-point improvement in DLQI score (moderate PGA: 59.9%; severe PGA: 60.8%) at the ~ 4-month visit that were comparable to those observed in UNVEIL (63.8%) at week 16, when the primary analysis of UNVEIL was reported [15]. Despite similar achievement of DLQI response in both PGA severity subgroups over time, greater proportions of patients with less severe psoriasis achieved early PASI treatment response versus patients with more severe psoriasis. Although patients with a PGA score of 2 or 3 had less skin involvement than those with a PGA score of 4, the two groups reported similar baseline disease burden, perhaps due to similar rates of scalp and nail involvement. Our findings suggest that the initiation of systemic therapies and effective interventions targeting psoriasis symptoms and special areas should be considered earlier in the course of disease severity, for example in patients with less skin disease but high disease burden due to psoriasis in special areas.

As noted in other real-world studies of apremilast [21, 22, 29], the most commonly reported AEs of diarrhoea, headache, nausea and upper respiratory tract infection were consistent with those reported in placebo-controlled trials [13,14,15, 30]. Strategies such as non-medical approaches (e.g. taking apremilast with a meal, adequate diet and hydration), antidiarrhoeal or anti-nausea medication, or probiotic use can help manage mild to moderate gastrointestinal AEs [31]. Many patients in LAPIS-PSO reported that they preferred apremilast and found it to be better tolerated than their prior systemic treatment. Taken together, findings from LAPIS-PSO are consistent with results from clinical trials of apremilast and provide additional information about patients’ experiences with apremilast treatment in clinical practice settings.

This study was limited by its non-interventional design, which can be susceptible to incomplete data collection. In addition to the as-observed analyses, we imputed missing values using LOCF to ensure that results would be representative of the entire study population. No major differences were observed using the two statistical methodologies. Although the number of patients analysed for the primary endpoint (n = 257) was slightly lower than planned (n = 290), no formal statistical analyses were performed and findings were consistent with the known efficacy and safety of apremilast as reported in clinical trials [13,14,15,16].

Conclusion

In conclusion, treatment with apremilast was associated with improvements in QOL and psoriasis disease severity that were sustained up to ~ 13 months, including patients with less severe and more severe psoriasis. These data confirm that apremilast can benefit patients who have high disease burden due to psoriasis in special areas and provide meaningful and sustained improvements in bothersome symptoms such as itch and skin pain. The safety profile of apremilast in this real-world study was consistent with the known safety profile observed in clinical trials.

References

Baliwag J, Barnes DH, Johnston A. Cytokines in psoriasis. Cytokine. 2015;73:342–50.

Lebwohl MG, Bachelez H, Barker J, Girolomoni G, Kavanaugh A, Langley RG, et al. Patient perspectives in the management of psoriasis: results from the population-based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis Survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:871–81.

Langley RG, Krueger GG, Griffiths CE. Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, and quality of life. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(Suppl 2):18–23.

Merola JF, Qureshi A, Husni ME. Underdiagnosed and undertreated psoriasis: nuances of treating psoriasis affecting the scalp, face, intertriginous areas, genitals, hands, feet, and nails. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31:e12589.

Mrowietz U, Kragballe K, Reich K, Spuls P, Griffiths CE, Nast A, et al. Definition of treatment goals for moderate to severe psoriasis: a European consensus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2011;303:1–10.

Augustin M, Sommer R, Kirsten N, Danckworth A, Radtke MA, Reich K, et al. Topology of psoriasis in routine care—results from a high-resolution analysis in 2009 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:358–65.

Sommer R, Augustin M, Mrowietz U, Topp J, Schafer I, von Spreckelsen R. Perception of stigmatization in people with psoriasis – qualitative analysis from the perspective of patients, relatives and healthcare professionals. Hautarzt. 2019;70:520–6.

Armstrong AW, Robertson AD, Wu J, Schupp C, Lebwohl MG. Undertreatment, treatment trends, and treatment dissatisfaction among patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in the United States: findings from the National Psoriasis Foundation surveys, 2003–2011. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1180–5.

Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, Feldman SR, Gelfand JM, Gordon KB, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 6. Guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: case-based presentations and evidence-based conclusions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:137–74.

Deeks ED. Apremilast: a review in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Drugs. 2015;75:1393–403.

Schafer P. Apremilast mechanism of action and application to psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:1583–90.

Otezla. Summary of product characteristics. Breda: Amgen Europe B.V.; 2020.

Papp K, Reich K, Leonardi CL, Kircik L, Chimenti S, Langley RG, et al. Apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor, in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results of a phase III, randomized, controlled trial (Efficacy and Safety Trial Evaluating the Effects of Apremilast in Psoriasis [ESTEEM 1]). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:37–49.

Paul C, Cather J, Gooderham M, Poulin Y, Mrowietz U, Ferrandiz C, et al. Efficacy and safety of apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis over 52 weeks: a phase III, randomized, controlled trial (ESTEEM 2). Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1387–99.

Strober B, Bagel J, Lebwohl M, Stein Gold L, Jackson JM, Chen R, et al. Efficacy and safety of apremilast in patients with moderate plaque psoriasis with lower BSA: week 16 results from the UNVEIL study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:801–8.

Reich K, Gooderham M, Bewley A, Green L, Soung J, Petric R, et al. Safety and efficacy of apremilast through 104 weeks in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis who continued on apremilast or switched from etanercept treatment: findings from the LIBERATE study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:397–402.

Van Voorhees AS, Gold LS, Lebwohl M, Strober B, Lynde C, Tyring S, et al. Efficacy and safety of apremilast in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis of the scalp: results of a phase 3b, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:96–103.

Masson Regnault M, Castañeda-Sanabria J, Diep Tran MHT, Beylot-Barry M, Bachelez H, Beneton N, et al. Users of biologics in clinical practice: would they be eligible for phase III clinical studies? Cohort Study in the French Psoriasis Registry PSOBIOTEQ. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:293–300.

Augustin M, Kleyn CE, Conrad C, Sator PG, Stahle M, Eyerich K, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients treated with apremilast in the real world: results from the APPRECIATE study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:123–34.

Reich A, Medrek K, Stander S, Szepietowski JC. Determination of minimum clinically important difference (MCID) of visual analogue scale (VAS): in which direction should we proceed? [abstract IL26]. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:609–10.

Mayba JN, Gooderham MJ. Real-world experience with apremilast in treating psoriasis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21:145–51.

Papadavid E, Rompoti N, Theodoropoulos K, Kokkalis G, Rigopoulos D. Real-world data on the efficacy and safety of apremilast in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;23:1173–1179.

Knuckles MLF, Levi E, Soung J. Treating moderate plaque psoriasis: prospective 6-month chart review of patients treated with apremilast. J Dermatol Treat. 2019;30:430–4.

Vujic I, Herman R, Sanlorenzo M, Posch C, Monshi B, Rappersberger K, et al. Apremilast in psoriasis—a prospective real-world study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:254–9.

Merola JF, Li T, Li WQ, Cho E, Qureshi AA. Prevalence of psoriasis phenotypes among men and women in the USA. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:486–9.

Egeberg A, See K, Garrelts A, Burge R. Epidemiology of psoriasis in hard-to-treat body locations: data from the Danish skin cohort. BMC Dermatol. 2020;20:3.

Augustin M, Langenbruch A, Gutknecht M, Reich K, Korber A, Maassen D, et al. Definition of psoriasis severity in routine clinical care: current guidelines fail to capture the complexity of long-term psoriasis management. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:1385–91.

Augustin M, Spehr C, Radtke MA, Boehncke WH, Luger T, Mrowietz U, et al. German psoriasis registry PsoBest: objectives, methodology and baseline data. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:48–57.

Ighani A, Georgakopoulos JR, Zhou LL, Walsh S, Shear N, Yeung J. Efficacy and safety of apremilast monotherapy for moderate to severe psoriasis: retrospective study. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22:290–6.

Reich K, Gooderham M, Green L, Bewley A, Zhang Z, Khanskaya I, et al. The efficacy and safety of apremilast, etanercept, and placebo, in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: 52-week results from a phase 3b, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (LIBERATE). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:507–17.

Pinter A, Beigel F, Körber A, Homey B, Beissert S, Gerdes S, et al. Gastrointestinal side effects of apremilast: characterization and management. Hautarzt. 2019;70:354–62.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and physicians who participated in the study.

Medical writing/editorial assistance

Writing support was funded by Amgen Inc. and provided by Amy Shaberman, PhD, and Kristin Carlin, BSPharm, MBA, of Peloton Advantage, LLC, an OPEN Health company, and Mandy Suggitt, Amgen Inc.

Disclosures

Kristian Reich: AbbVie, Affibody, Almirall, Amgen Inc., Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene Corporation, Centocor, Covagen, Fresenius Medical Care, Janssen-Cilag, Miltenyi Biotec, Ortho Biotech, Eli Lilly, Forward Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline, Kyowa Hakko Kirin Pharma, LEO Pharma, Lilly ICOS, Medac Pharma, Merck & Co., Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Samsung, Sanofi, Takeda, UCB, Valeant, and XenoPort—speaker/advisory board/data safety monitoring board, honoraria. Bernhard Korge: AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Astella, Beiersdorf, Biogen, Celgene, Dr. Pfleger, Galderma, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Medac, Sanofi, and UCB—served as an advisor. Nina Magnolo: AbbVie, Asana, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene Corporation, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Genentech, Incyte, Janssen-Cilag, Kyowa Kirin, LEO Pharma, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sun Pharma, and UCB Pharma—honoraria, advisor, and/or paid speaker for and/or participated in clinical trials. Maria Manasterski: Nothing to disclose. Uwe Schwichtenberg: AbbVie Deutschland GmbH, Almirall Hermal GmbH, Amgen, Beiersdorf Dermo Medical GmbH, Celgene GmbH, Janssen Cilag GmbH, Johnson & Johnson GmbH, LEO Pharma GmbH, L´Oréal GmbH, MEDA Pharma GmbH, Medical Project Design GmbH, Merz Pharmaceuticals GmbH, MSD SHARP & DOHME GmbH, Novartis Pharma GmbH, and Pfizer GmbH—salary, investigator, advisory board, speaker, and/or stockholder. Petra Staubach-Renz: Amgen and Celgene GmbH—personal fees, non-financial support. Stephan Kaiser, Josefine Roemmler-Zehrer, and Katrin Lorenz-Baath: Amgen GmbH—former employment. Natalie Núnez Gómez: Bristol Myers Squibb—former employment. Celgene Corporation—employment at the time of study conduct.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

An independent ethics committee (FEKI; Freiburger Ethikkommission International, reference 015/1385) approved the study protocol, and all patients provided written, informed consent before participating. Local ethics committees approved the protocol for participating study sites (UK RUB Ruhruniversität Bochum, reference 52/2015; Sächsische Landesärztkammer, reference RN EK-BR-74/15-1; Medizinische Fakultät Mannheim, reference 2015-905W-MA; Ethikkommission der Technischen Universität Dresden, reference EK472112015; Medizinische Fakultät der Universität Duisburg-Essen, reference 16-6844-BO). The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Funding

This study was funded by Celgene and Amgen. Amgen acquired the worldwide rights to Otezla® (apremilast) on November 21, 2019. Writing support and the journal’s Rapid Service fee were funded by Amgen Inc.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author contributions

KR, SK, JR-Z, NNG, and KL-B contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and/or analysis were performed by KR, BK, NM, MM, US, PS-R, SK, JR-Z, NNG, and KL-B. All authors contributed to drafting of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Prior presentation

Reich K, Fritzlar S, Korge B, et al. Physician- and Patient-Reported Outcomes in Patients With Moderate to Severe Plaque Psoriasis Treated With Apremilast During Routine Dermatology Care in Germany. Presented at: Deutsche Dermatologische Gesellschaft (DDG) Dermatologie Kompakt & Praxisnah 2020; February 7–9, 2020; Dresden, Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Reich, K., Korge, B., Magnolo, N. et al. Quality-of-Life Outcomes, Effectiveness and Tolerability of Apremilast in Patients with Plaque Psoriasis and Routine German Dermatology Care: Results from LAPIS-PSO. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 12, 203–221 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-021-00658-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-021-00658-x