Abstract

Atopic dermatitis (AD), the leading cause of skin-related burden of disease worldwide, is increasing in prevalence in developing countries of Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East. Although AD presents similarly across racial and ethnic groups as chronic and relapsing pruritic eczematous lesions, some features of the disease may be more or less prominent in patients with darker skin. Despite a similar presentation, consistent diagnostic criteria and consistent treatment guidelines are lacking. Because of these and other challenges, adherence to treatment guidelines is difficult or impossible. Previous studies have stated that many patients with AD receive ineffective or inappropriate care, such as oral antihistamines, oral corticosteroids, or traditional medicines, if they are treated at all; one study showed that approximately one-third of patients received medical care for their dermatologic condition; of those, almost three-quarters received inappropriate or ineffective treatment. In addition, other challenges endemic to developing countries include cost, access to care, and lack of specialists in AD. Furthermore, most of the available diagnostic criteria and treatment guidelines are based on European and North American populations and few clinical trials report the racial or ethnic makeup of the study population. Drug pharmacokinetics in varying ethnicities and adverse effects in different skin physiologies are areas yet to be explored. The objective of this review is to describe the diagnosis, treatment, and management of AD in developing countries in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East; to discuss the differences among the countries; and to establish the unmet needs of patients with AD in them. The unmet medical need for treatment of AD in developing countries can be addressed by continuing to train medical specialists, improve access to and affordability of care, and develop new and effective treatments.

Funding Pfizer Inc.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, relapsing-remitting skin disease characterized by pruritic eczematous lesions [1], and it is the leading cause of skin-related burden of disease globally [2]. The pathogenesis of AD is multifactorial and includes genetic factors, which have been shown to vary across racial groups [3,4,5]. The pathogenesis of AD also depends on environmental factors; as a result, there are wide variations in epidemiology from country to country [5, 6]. Although it seems to have leveled off in developed countries, AD prevalence appears to be increasing in developing countries [7], likely because of increasing urbanization, pollution, Western diet consumption, and obesity [6]. Among 13- to 14-year-old adolescents in the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Phase 3, AD prevalence for Africa and Latin America was high at 12–14% and 6–10%, respectively, whereas for Asian-Pacific countries, the Eastern Mediterranean region, and the Indian subcontinent values were lower at 3–6%; among 6- to 7-year-old children, AD prevalence for Asian-Pacific countries, Africa, and Latin America was high at approximately 10%, whereas values for the Eastern Mediterranean region and Indian subcontinent were lower at 3–5% [8]. Likewise, prevalence in the first 2 years of life was also high at 7–27% in Asian-Pacific countries, including South Korea [9], China [10], Singapore [11], Malaysia [12], and Taiwan [13,14,15]. This review presents the diagnosis, treatment, and management of AD in developing countries in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East. We discuss the differences in epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment among the countries to establish the unmet needs of patients with AD living in these countries. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Clinical Presentation

Overall, AD presents similarly across racial and ethnic groups as chronic or relapsing pruritic eczematous skin lesions; however, some features may be more or less prominent in patients with darker skin. Erythema is often less obvious in patients with darker skin and may appear reddish-blue or purple (violaceous) rather than red [5, 16]. Perifollicular accentuation, papulation, scaling, lichenification, and pigmentary changes may also be more prominent in patients with darker skin [5, 16, 17]. In addition, Asian populations demonstrate greater helper T cell (Th) 17/Th22 polarization than other populations, leading to a phenotype that combines features of AD and psoriasis [5, 18]. The pattern of lesions may also vary, with patients who have darker skin tones being more likely to present with lesions on extensor surfaces rather than the typical pattern of predominantly flexural lesions [5, 16, 17, 19, 20].

Differences in age of onset, disease severity, and genetic susceptibility may occur across racial and ethnic groups. The prevalence of AD in adults appears to be greater among some Asian populations, potentially because of higher rates of disease onset in adulthood [16, 20,21,22,23]. Although their prevalence of the two most common filaggrin (FLG) mutations leading to AD (R501X and 2282del4) is lower, patients of African descent appear to be at greater risk for severe AD [16, 17]. Other studies have reported the prevalence of different FLG mutations in Asian patients (S1695X, Q1701X, Q1745X, Y1767X, Q1790X, S2554X, S2889X, S3296X, 3222del4, S1515X, Q2417X, and K4022X) and Middle Eastern patients (S417S and D1921N, among others) [24, 25]. Pruritus may be more severe in patients with darker skin [17, 19, 26, 27]. It must be noted, however, that many of the available data on differences in clinical presentations are based on data from patients of African descent living in the US or Europe, not in developing countries.

Diagnostic Criteria

Hanifin and Rajka diagnostic criteria [28] and the UK Working Party’s diagnostic criteria [29] have both been used to diagnose AD in Chinese [30, 31], Taiwanese [32], Indian [33], and South African [34] patients (Table 1). However, in a survey of Southeast Asian dermatologists, all Indonesian respondents (100%) were familiar with the UK Working Party’s diagnostic criteria, whereas respondents from Malaysia (73%), Singapore (75%), or Thailand (90%) were more familiar with the Hanifin and Rajka criteria, but less than half of the Filipino and Vietnamese respondents (5–39%) were familiar with either set of criteria [35].

Some population-specific diagnostic criteria have been proposed (Table 1). Liu et al. [22] proposed criteria for the diagnosis of AD in Chinese adults and adolescents that are based on only two features—persistent or recurrent symmetrical AD for > 6 months with one or both of the following: (1) personal or familial history of atopy and/or (2) elevated total serum immunoglobulin (Ig) E level, positive allergen-specific IgE, and/or eosinophilia. In an earlier iteration, Kang and Tian [36] proposed criteria for diagnosis in Chinese patients (regardless of age) based on the presence of two basic features (chronic or chronically relapsing pruritic dermatitis and personal or family history of atopy) or the first basic feature plus ≥ 3 minor features (onset before 12 years of age; xerosis, ichthyosis, or palmar hyperlinearity; allergic conjunctivitis, food intolerance, immediate skin reactivity, eosinophilia, or elevated serum IgE level; tendency to cutaneous infections or impaired cell-mediated immunity; facial pallor, white dermatographism, or delayed blanch; periorbital darkening, perifollicular accentuation, or tendency to nonspecific hand and foot dermatitis). Wisuthsarewong and Viravan [37] proposed and Wanitphakdeedecha et al. [38] validated criteria for the diagnosis of AD in Thai patients older than 13 years based on a history of flexural dermatitis plus ≥ 2 of the following: duration > 6 months, visible flexural dermatitis, and visible dry skin. The Korean Atopic Dermatitis Association [39] proposed the Reliable Estimation of Atopic Dermatitis of ChildHood (REACH) diagnostic criteria for South Korean children 4–12 years of age based on the presence of 2 major features (remitting-relapsing itchy rash in the past 12 months, itchy rash on antecubital/popliteal fossae in the past 12 months) or 1 major feature and ≥ 4 minor features (personal/family history of atopy; itchy rash around/on the eyes, ears, lips, neck, infragluteal folds, wrist/ankle joints; or itch when sweating in the past 12 months; unusually dry skin in past 12 months). Last, the South African Childhood Atopic Eczema Working Group [40] proposed criteria for South African children based on the presence of pruritus plus ≥ 3 of the following: flexural dermatitis, previous flexural dermatitis, dry skin, other atopic disease, and/or onset before 2 years of age.

The American Academy of Dermatology has published diagnostic criteria as well [41]. These are largely based on the Hanifin and Rajka criteria [28].

Treatment Guidelines

Treatment guidelines are available for Asian-Pacific countries overall [42, 43] and Taiwan [44], Singapore [45], South Korea [46,47,48], and India [49,50,51], specifically; Latin America overall [52] and Mexico [53, 54] and Argentina [55] specifically; South Africa [40, 56, 57]; and the Middle East [58] (Table 2). Unfortunately, no treatment guidelines could be identified for other countries in Africa or the Middle East. It is not clear whether emerging market-specific criteria are preferred by physicians. One survey of South Korean physicians found that 97% of pediatric allergists preferred the South Korea-specific allergy guidelines, whereas dermatologists preferred the South Korean, European, and American dermatology guidelines about equally [59].

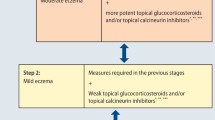

All of these treatment guidelines largely reflect the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) [41, 60,61,62], the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (AAAAI)/American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (ACAAI) [63], and European guidelines [64, 65], with skin care and hydration, trigger avoidance, topical anti-inflammatory drugs [topical corticosteroids (TCSs) or topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs)] as first-line treatment for mild-to-moderate AD; short courses of systemic corticosteroids and phototherapy as second-line treatment for moderate-to-severe AD; and systemic immunosuppressive therapies or biologics if further treatment is necessary for severe AD. However, some do differ in their recommendations regarding TCI use—the Middle Eastern [58] and Latin American guidelines [52], and one of the Mexican [54] (but not the other Mexican [53] or Argentinian [55] guidelines) recommend TCIs as first-line treatment, whereas one of the South African guidelines [57] is silent on this, and the rest recommend TCIs as second-line treatment. Regarding oral antihistamine use, one of the Mexican [54], one of the South Korean [47], and one of the South African [57] guidelines recommend them for pruritus relief; however, the rest only suggest the use of oral antihistamines in the context of other atopic comorbidities or for their sedating effects. Some guidelines also specifically address issues with AD management in tropical and subtropical regions, including the occlusiveness of ointments/emollients and the practicality of wet wrap therapy in hotter, more humid climates [42, 52, 66].

Guideline Adherence/Pharmacologic Treatment Utilization

Adherence to treatment guidelines was quite good regarding topical treatment of AD in surveys of physicians in Southeast Asia; however, adherence to systemic treatments was not as high. The use of emollients for clearance and maintenance was high (98–100% and 86–100%, respectively) among dermatologists surveyed from the Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore but was significantly less likely among dermatologists from Vietnam or Indonesia [35]. The use of topical anti-inflammatory therapies was also quite high, with 91–100% of respondents prescribing TCSs [35, 59]. The majority (86–90%) of respondents from Singapore, Thailand, and South Korea had used TCIs; however, few (9–24%) of the respondents from Indonesia, Malaysia, or Vietnam had used them, mostly because of a lack of access to these medications (55–67%) [35, 59].

The use of oral antihistamines (86–100%) and oral corticosteroids (67–100%) was quite high [35, 59], despite the lack of recommendations for their use or against it. Single-center studies conducted in India and Pakistan showed that most patients are treated with emollients (95%) and topical anti-inflammatory therapies (75%, nearly all TCSs) [20, 67, 68] in accordance with guidelines. However, 75% of patients received antihistamines [20] and 25–78% received oral corticosteroids, although they were prescribed on a short-term basis [20, 67]. Although treatment guidelines caution against chronic use of systemic corticosteroids, they are used this way quite frequently in Latin America [52].

Utilization of Traditional/Herbal Remedies

The Asian-Pacific, Taiwanese, and South Korean guidelines recommend that patients be advised about the lack of high-quality evidence to support the use of traditional/herbal remedies [42,43,44, 47]. Accordingly, a majority of Southeast Asian dermatologists surveyed do not recommend the use of these alternative treatments [35]. However, in many developing countries, traditional medicine continues to play an important role in meeting healthcare needs [69]. In surveys of South Korean patients with AD, approximately 70% reported using complementary alternative medicine (i.e., bath therapy, dietary therapy, health supplements, massage, traditional Chinese medicine, topical applicants) [70, 71]. In Brazilian AD and Nigerian dermatology populations, the prevalence of use was only slightly less at 64% and 65%, respectively [72, 73].

In areas of limited resources, these remedies are often more accessible and less expensive than pharmacologic treatments; however, their efficacy may be limited and is largely unproven. In fact, only 32% of South Korean users believed that their AD had improved with complementary alternative medicine [71]. A recent Cochrane review failed to find sufficient high-quality evidence to support the use of Chinese herbal medicine [74], and 76% of allergists and dermatologists surveyed in South Korea believe that the lack of evidence for complementary alternative medicine was a barrier to proper AD management. Although traditional/herbal remedies are often perceived as being safer than pharmacologic treatments, they are not without some concerning potential side effects, including liver and kidney toxicity, and are more often subject to contamination [5, 75]. However, the greater use of these alternative treatments observed in older children with longer-standing disease [72, 76, 77] and children with more atopic comorbidities/higher IgE levels—although this difference was not significant [76, 77]—may reflect frustration with pharmacologic treatments or fear of using higher doses of pharmacologic treatments for more severe/recalcitrant disease. In fact, approximately one-third of traditional Chinese medicine users (31–36%) use it in combination with corticosteroids or other “Western medicine” [76, 77], possibly in an effort to reduce the need for TCSs [78] (see the Challenges in AD Management section for more information on TCS misuse).

Challenges in AD Management

Some challenges in AD management are universal. Thus far, no cure exists for AD, and treatment is targeted at symptom management. Currently available treatments for severe AD are costly and require subcutaneous injection (e.g., dupilumab [79]) or associated with significant adverse effects (e.g., systemic corticosteroids [80]). Topical corticosteroids, the mainstay of treatment for mild-to-moderate AD, require complex dosing regimens (i.e., low potency for the face and neck, higher potency for other body areas) [81], are associated with significant adverse effects when used chronically [82], and can lead to hypopigmentation in darker skin [5, 16]. These problems have led to corticosteroid phobia among many patients with AD and underuse and/or nonuse of prescribed TCSs [40, 59, 70, 83]. However, in India, most TCSs are available over the counter, which has led to misuse [84, 85]; efforts are underway to curtail this practice by making TCSs available by prescription only [86].

Other challenges are more specific to developing countries. Limited/ineffective healthcare systems [59, 87] and a lack of specialists with training in the management of AD [59, 88] are among the major challenges. In addition, regional differences in availability (Table 3) [89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120] present a challenge, as does the cost of AD treatment [121, 122], especially for newer, more effective treatments [123,124,125]. Lower socioeconomic status can also have a negative impact on access to care and adherence to treatment [17, 121], and the differences in clinical presentation and symptoms for patients with darker skin tones and different ethnic origins mentioned above may lead to delayed diagnosis and, in turn, more severe disease at diagnosis.

Other challenges arise from the fact that most diagnostic criteria and guidelines have been developed for European and North American populations, and very few clinical studies of dermatologic treatments (11%) conducted outside/not exclusively within the US even report the racial or ethnic makeup of the study population [126]. Although approximately 60% of US-based studies do include such information [126, 127], the applicability to developing countries is, of course, limited because of differences in environment, etc.

The efficacy and safety of several treatments have been assessed in patients living in developing countries (including tacrolimus for patients in China [128], South Korea [129], Thailand [130], and Bangladesh [131]; TCSs for patients in Singapore [132], India [133], and Bangladesh [131]; and methotrexate for patients in Egypt [134]). In one analysis, results from clinical studies of tacrolimus conducted in eight Asian countries (China, Indonesia, South Korea, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, and Thailand) were pooled and found to be similar to those observed for studies conducted in the US and Europe [135]. However, differences between racial groups in drug pharmacokinetics and skin physiology may affect treatment response (although to a lesser degree than other factors, such as age and skin barrier function), and the potential for these differences to affect outcomes remains largely unexplored [5].

Conclusions

Globally, a substantial unmet medical need exists in AD management. This need is magnified in developing countries by many of the factors discussed above and may lead to inadequate or inappropriate treatment. In fact, 15% of patients in one community-based study in Singapore reported receiving no treatment [136]. In another study, only 36% of patients in an area of North India with limited resources sought medical care for their dermatologic condition, and 69% received inappropriate or ineffective treatment according to the authors [137].

Increased training of primary care physicians and specialists, changes in healthcare systems to improve access and affordability of care, and the development of new and more effective treatments will help reduce this unmet need. In addition, innovations in healthcare delivery such as teledermatology [138, 139] and task sharing/shifting [140] may also improve patient care. Patient and caregiver education may also improve AD treatment adherence and clinical outcomes as well as patient and family quality of life in developing countries [141,142,143,144,145].

References

Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2016;387:1109–22.

Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1527–34.

Al-Shobaili HA, Ahmed AA, Alnomair N, Alobead ZA, Rasheed Z. Molecular genetic[sic] of atopic dermatitis: an update. Int J Health Sci (Qassim). 2016;10:96–120.

Brown SJ, McLean WH. One remarkable molecule: filaggrin. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:751–62.

Kaufman BP, Guttman-Yassky E, Alexis AF. Atopic dermatitis in diverse racial and ethnic groups-variations in epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:340–57.

Nutten S. Atopic dermatitis: global epidemiology and risk factors. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66(Suppl 1):8–16.

Williams H, Stewart A, von Mutius E, Cookson W, Anderson HR, International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Phase One and Three Study Groups. Is eczema really on the increase worldwide? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:947–54.

Mallol J, Crane J, von Mutius E, Odhiambo J, Keil U, Stewart A, ISAAC Phase Three Study Group. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Phase Three: a global synthesis. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2013;41:73–85.

Lee SI, Kim J, Han Y, Ahn K. A proposal: Atopic Dermatitis Organizer (ADO) guideline for children. Asia Pac Allergy. 2011;1:53–63.

Guo Y, Li P, Tang J, et al. Prevalence of atopic dermatitis in Chinese children aged 1–7 ys. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29751.

Tan TN, Lim DL, Lee BW, Van Bever HP. Prevalence of allergy-related symptoms in Singaporean children in the second year of life. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2005;16:151–6.

Goh YY, Keshavarzi F, Chew YL. Prevalence of atopic dermatitis and pattern of drug therapy in Malaysian children. Dermatitis. 2018;29:151–61.

Hwang CY, Chen YJ, Lin MW, et al. Prevalence of atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis and asthma in Taiwan: a national study 2000 to 2007. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:589–94.

Wang IJ, Guo YL, Weng HJ, et al. Environmental risk factors for early infantile atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2007;18:441–7.

Wang IJ, Huang LM, Guo YL, Hsieh WS, Lin TJ, Chen PC. Haemophilus influenzae type b combination vaccines and atopic disorders: a prospective cohort study. J Formos Med Assoc. 2012;111:711–8.

Mei-Yen Yong A, Tay YK. Atopic dermatitis: racial and ethnic differences. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:395–402.

Vachiramon V, Tey HL, Thompson AE, Yosipovitch G. Atopic dermatitis in African American children: addressing unmet needs of a common disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:395–402.

Noda S, Suarez-Farinas M, Ungar B, et al. The Asian atopic dermatitis phenotype combines features of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis with increased TH17 polarization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:1254–64.

Tey HL, Yosipovitch G. Itch in ethnic populations. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:227–34.

Scaria S, James E, Dharmaratnam AD. Epidemiology and treatment pattern of atopic dermatitis in patients attending a tertiary care teaching hospital. Int J Res Pharmaceutical Sci. 2011;2:38–44.

Wang X, Shi XD, Li LF, Zhou P, Shen YW, Song QK. Prevalence and clinical features of adult atopic dermatitis in tertiary hospitals of China. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e6317.

Liu P, Zhao Y, Mu ZL, et al. Clinical features of adult/adolescent atopic dermatitis and Chinese criteria for atopic dermatitis. Chin Med J (Engl). 2016;129:757–62.

Tay YK, Khoo BP, Goh CL. The epidemiology of atopic dermatitis at a tertiary referral skin center in Singapore. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 1999;17:137–41.

On HR, Lee SE, Kim SE, et al. Filaggrin mutation in Korean patients with atopic dermatitis. Yonsei Med J. 2017;58:395–400.

Hassani B, Isaian A, Shariat M, et al. Filaggrin gene polymorphisms in Iranian ichthyosis vulgaris and atopic dermatitis patients. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1485–91.

Weisshaar E, Dalgard F. Epidemiology of itch: adding to the burden of skin morbidity. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:339–50.

Hajdarbegovic E, Thio HB. Itch pathophysiology may differ among ethnic groups. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:771–6.

Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1980;60:44–7.

Williams HC, Burney PG, Pembroke AC, Hay RJ. The UK Working Party’s diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis. III. Independent hospital validation. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:406–16.

Wang L, Li LF, Professional Committee of Dermatology, Chinese Association of Integrative Medicine. Clinical application of the UK Working Party’s criteria for the diagnosis of atopic dermatitis in the Chinese population by age group. Chin Med J (Engl). 2016;129:2829–33.

Gu H, Chen XS, Chen K, et al. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis: validity of the criteria of Williams et al. in a hospital-based setting. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:428–33.

Lan CC, Lee CH, Lu YW, et al. Prevalence of adult atopic dermatitis among nursing staff in a Taiwanese medical center: a pilot study on validation of diagnostic questionnaires. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:806–12.

De D, Kanwar AJ, Handa S. Comparative efficacy of Hanifin and Rajka’s criteria and the UK Working Party’s diagnostic criteria in diagnosis of atopic dermatitis in a hospital setting in North India. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:853–9.

Chalmers DA, Todd G, Saxe N, et al. Validation of the UK Working Party diagnostic criteria for atopic eczema in a Xhosa-speaking African population. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:111–6.

Chan YC, Tay YK, Sugito TL, et al. A study on the knowledge, attitudes and practices of Southeast Asian dermatologists in the management of atopic dermatitis. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2006;35:794–803.

Kang KF, Tian RM. Criteria for atopic dermatitis in a Chinese population. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh). 1989;144:26–7.

Wisuthsarewong W, Viravan S. Diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis in Thai children. J Med Assoc Thai. 2004;87:1496–500.

Wanitphakdeedecha R, Tuchinda P, Sivayathorn A, Kulthanan K. Validation of the diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis in the adult Thai population. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2007;25:133–8.

Lee SC, Bae JM, Lee HJ, Korean Atopic Dermatitis Association’s Atopic Dermatitis Criteria Group, et al. Introduction of the Reliable Estimation of Atopic dermatitis in ChildHood: novel, diagnostic criteria for childhood atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2016;8:230–8.

Manjra AI, du Plessis P, Weiss R, South African Childhood Atopic Eczema Working Group, et al. Childhood atopic eczema consensus document. S Afr Med J. 2005;95:435–40.

Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:338–51.

Rubel D, Thirumoorthy T, Soebaryo RW, Asia-Pacific Consensus Group for Atopic Dermatitis, et al. Consensus guidelines for the management of atopic dermatitis: an Asia-Pacific perspective. J Dermatol. 2013;40:160–71.

Chow S, Seow CS, Dizon MV, et al. Asian Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. A clinician’s reference guide for the management of atopic dermatitis in Asians. Asia Pac Allergy. 2018;8:e41.

Chu C-Y, Lee C-H, Shih IH, et al. Taiwanese Dermatological Association consensus for the management of atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Sin. 2015;33:220.

Tay YK, Chan YC, Chandran NS, et al. Guidelines for the management of atopic dermatitis in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2016;45:439–50.

Kim JE, Kim HJ, Lew BL, et al. Consensus guidelines for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in Korea (part I): general management and topical treatment. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:563–77.

Kim JE, Kim HJ, Lew BL, et al. Consensus guidelines for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in Korea (Part II): systemic treatment. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:578–92.

Park J-S, Kim B-J, Park Y, KAAACI Work Group on Severe/Recalcitrant Atopic Dermatitis, et al. KAAACI work group report on the treatment of severe/recalcitrant atopic dermatitis. J Asthma Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;30:255–70.

Dhar S, Parikh D, Rammoorthy R, et al. Treatment guidelines for atopic dermatitis by ISPD task force 2016. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2017;18:174.

Dhar S, Parikh D, Srinivas S, et al. Treatment guidelines for atopic dermatitis by Indian Society for Pediatric Dermatology task force 2016—Part-2: topical therapies in atopic dermatitis [IJPD symposium]. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2017;18:274.

Parikh D, Dhar S, Ramamoorthy R, et al. Treatment guidelines for atopic dermatitis by ISPD task force 2016 [IJPD symposium]. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2018;19:108–15.

Sanchez J, Paez B, Macias A, Olmos C, de Falco A. Atopic dermatitis guideline. Position paper from the Latin American Society of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Rev Alerg Mex. 2014;61:178–211.

Centro Nacional de Excelencia Tecnológica. Guía de Práctica Clínica: Tratamiento de la Dermatitis Atópica. México: Secretaría de Salud; 2014. http://www.cenetec.salud.gob.mx/descargas/gpc/CatalogoMaestro/IMSS-706-14-TxDermatitisatopica/706GER.pdf. Accessed 27 Jul 2018.

Rincon-Perez C, Larenas-Linnemann D, Figueroa-Morales MA, et al. Mexican consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adolescents and adults. Rev Alerg Mex. 2018;65(Suppl 2):s8–88.

Comite Nacional de Dermatologia. Atopic dermatitis: national consensus 2013. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2014;112:293–4.

Sinclair W, Aboobaker J, Jordaan F, Modi D, Todd G. Management of atopic dermatitis in adolescents and adults in South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2008;98:303–19.

Republic of South Africa Essential Drugs Programme. Primary healthcare standard treatment guidelines and essential medicines list. 5th ed. Republic of South Africa: National Department of Health; 2014. http://www.kznhealth.gov.za/pharmacy/edlphc2014a.pdf. Accessed 11 Sep 2018.

Reda AM, Elgendi A, Ebraheem AI, et al. A practical algorithm for topical treatment of atopic dermatitis in the Middle East emphasizing the importance of sensitive skin areas. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;30:1–8.

Yum HY, Kim HH, Kim HJ, KAAACI Work Group on Severe/Recalcitrant Atopic Dermatitis, et al. Current management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a survey of allergists, pediatric allergists and dermatologists in Korea. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2018;10:253–9.

Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. Management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116–32.

Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, American Academy of Dermatology, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327–49.

Sidbury R, Tom WL, Bergman JN, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 4. Prevention of disease flares and use of adjunctive therapies and approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1218–33.

Schneider L, Tilles S, Lio P, et al. Atopic dermatitis: a practice parameter update 2012. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:295–9.

Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, European Dermatology Forum (EDF), The European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV), The European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI), et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:657–82.

Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, European Dermatology Forum (EDF), The European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV), The European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI), et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:820–78.

Dhar S. Topical therapy of atopic dermatitis. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2013;14:4.

Rajar UDM, Kazi N, Kazi SAF. The profile of atopic dermatitis in out patient department of dermatology Isra University Hospital. Med Forum Mon. 2015;26:10–3.

Dilnawaz M, Sheikh ZI. Clinical audit of national institute of clinical excellence (NICE) technology appraisal guidance (TAG) 81 and 82/clinical guidelines (CG57) on atopic eczema in children. J Pak Assoc Dermatol. 2013;23:47–51.

World Health Organization. WHO traditional medicine strategy: 2014–2023. 2013. http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/92455. Accessed 11 Sep 2018.

Kim DH, Kang KH, Kim KW, Yoo IY. Management of children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Allergy Respir Dis. 2008;18:148–57.

Kim GW, Park JM, Chin HW, et al. Comparative analysis of the use of complementary and alternative medicine by Korean patients with androgenetic alopecia, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:827–35.

Aguiar Júnior N, Costa IM. The use of alternative or complementary medicine for children with atopic dermatitis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:167–8.

Ajose FO. Some Nigerian plants of dermatologic importance. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(Suppl 1):48–55.

Gu S, Yang AW, Xue CC, et al. Chinese herbal medicine for atopic eczema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:CD008642.

Chan K. Chinese medicinal materials and their interface with Western medical concepts. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;96:1–18.

Chen YC, Lin YH, Hu S, Chen HY. Characteristics of traditional Chinese medicine users and prescription analysis for pediatric atopic dermatitis: a population-based study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16:173.

Lin JF, Liu PH, Huang TP, et al. Characteristics and prescription patterns of traditional Chinese medicine in atopic dermatitis patients: ten-year experiences at a medical center in Taiwan. Complement Ther Med. 2014;22:141–7.

Chen HY, Lin YH, Wu JC, et al. Use of traditional Chinese medicine reduces exposure to corticosteroid among atopic dermatitis children: a 1-year follow-up cohort study. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;159:189–96.

Kuznik A, Bego-Le-Bagousse G, Eckert L, et al. Economic evaluation of dupilumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adults. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:493–505.

Liu D, Ahmet A, Ward L, et al. A practical guide to the monitoring and management of the complications of systemic corticosteroid therapy. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2013;9:30.

Eichenfield LF, Boguniewicz M, Simpson EL, et al. Translating atopic dermatitis management guidelines into practice for primary care providers. Pediatrics. 2015;136:554–65.

Hengge UR, Ruzicka T, Schwartz RA, Cork MJ. Adverse effects of topical glucocorticosteroids. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1–15.

Li Y, Han T, Li W, Li Y, Guo X, Zheng L. Awareness of and phobias about topical corticosteroids in parents of infants with eczema in Hangzhou, China. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:463–7.

Saraswat A, Lahiri K, Chatterjee M, et al. Topical corticosteroid abuse on the face: a prospective, multicenter study of dermatology outpatients. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:160–6.

Mukherjee S, Era N, Banerjee G, Kumar Tripathi S. Assessment of corticosteroid utilization pattern among dermatology outpatients in a tertiary care teaching hospital in Eastern India. Int J Green Pharm. 2016;10:S178.

Coondoo A. Topical corticosteroid misuse: the Indian scenario. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:451–5.

Obeng BB, Hartgers F, Boakye D, Yazdanbakhsh M. Out of Africa: what can be learned from the studies of allergic disorders in Africa and Africans? Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;8:391–7.

Meintjes KF, Nolte AG. Parents’ experience of childhood atopic eczema in the public health sector of Gauteng. Curationis. 2015;38:1215.

China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA). Database of approved active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and API manufacturers in China [online database]. http://app1.sfda.gov.cn/datasearcheng/face3/base.jsp?tableId=85&tableName=TABLE85&title=Database%20of%20approved%20Active%20Pharmaceutical%20Ingredients%20(APIs)%20and%20API%20manufacturers%20in%20China&bcId=136489131226659132460942000667. Accessed 27 Aug 2018.

Drug Office, Department of Health, The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Drug database [online database]. http://www.drugoffice.gov.hk/eps/do/en/consumer/search_drug_database.html. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

Badan Pengawas Obat dan Makanan Republik Indonesia. Cek produk BPOM [online database]. http://cekbpom.pom.go.id/. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

Bahagian Regulatori Farmasi Negara (NPRA), Malaysia. QUEST 3+ sistem pPendaftaran produk and perlesena [online database]. http://npra.moh.gov.my/q3plus/index.php/products-search. Accessed 27 Aug 2018.

Food and Drug Administration, Republic of Philippines. Registered drugs [online database]. https://ww2.fda.gov.ph/index.php/consumers-corner/registered-drugs-2. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

Health Sciences Authority, Singapore Government. Register of therapeutic products [online database]. https://eservice.hsa.gov.sg/prism/common/enquirepublic/SearchDRBProduct.do?action=load. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

Ministry of Food and Drug Safety, Republic of Korea. Drug search [online database]. http://www.mfds.go.kr/eng/search/searchEn.do. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

Food and Drug Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare. [Western medicine, medical equipment, medicine-containing cosmetics license inquiry] [online database]. https://www.fda.gov.tw/MLMS/H0001.aspx. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

MIMS-Thailand. Drug advanced search [online database]. http://www.mims.com/thailand/drug/advancedsearch/. Accessed 28 Aug 2018.

MIMS-Vietnam. [Advanced drug search] [online database]. http://www.mims.com/vietnam/drug/advancedsearch/. Accessed 28 Aug 2018.

BDdrugs.com. Drug index of Bangladesh [online database]. http://bddrugs.com/product1.php. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

Medline India. Generic index [online database]. http://www.medlineindia.com/generic%20index.html. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan. Registered drugs [online database]. https://public.dra.gov.pk/rd/HTMLClient/default.htm. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

Administración Nacional de Medicamentos, Alimentos y Tecnología Médica (ANMAT), Ministerio de Salud, Presidente de la Nación Argentina. Vademécum nacional de medicamentos [online database]. https://servicios.pami.org.ar/vademecum/views/consultaPublica/listado.zul. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA), Brazil. Medicamentos [online database]. https://consultas.anvisa.gov.br/#/medicamentos/. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

Ministerio de Salud, Chile. Medicamentos [online database]. https://www.tufarmacia.gob.cl/. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

Instituto Nacional de Vigilancia de Medicamentos Alimentos (INVIMA), Minsalud, Gobierno de Colombia. Consulta datos de productos [online database]. http://consultaregistro.invima.gov.co:8082/Consultas/consultas/consreg_encabcum.jsp. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

gob.mx. Consulta de registros sanitarios [online database]. http://tramiteselectronicos02.cofepris.gob.mx/BuscadorPublicoRegistrosSanitarios/BusquedaRegistroSanitario.aspx. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

Ministerio de Salud, Perú. Registro sanitario de productos farmacéuticos [online database]. http://www.digemid.minsa.gob.pe/ProductosFarmaceuticos/principal/pages/Default.aspx. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

Instituto Nacional de Higiene “Rafael Rangel”, Ministerio del Poder Popular para la Salud, Gobierno Bolivariano de Venezuela. Especialidades farmacéuticas aprobadas [online database]. http://www.inhrr.gob.ve/ef_aprobadas.php. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

Egyptian Drug Authority. Registered drugs [online database]. http://196.46.22.218/EDASearch/SearchRegDrugs.aspx. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

Direction du Médicament et de la Pharmacie, Maroc. Informations sur les médicaments [online database]. http://dmp.sante.gov.ma/recherche-medicaments. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

National Agency for Food and Drug Adminstration and Control (NAFDAC), Nigeria. NAFDAC approved and registered drugs database [online database]. https://www.nafdac.gov.ng/drugs/drug-database/. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

South African Health Products Regulatory Authority. Registration notifications [online database]. http://www.sahpra.org.za/Publications/Index/14. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

DPM Tunisie. Il s’agit de la liste des DCI enregistrées [online database]. http://www.dpm.tn/index.php/medicaments-a-usage-humain/liste-des-dci. Accessed 27 Aug 2018.

Jordan Food and Drug Administration. List of rational use of medicines. http://www.jfda.jo/Pages/viewpage.aspx?pageID=175. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

Republic of Lebanon, Ministry of Public Health. Lebanon national drugs database [online database]. http://www.moph.gov.lb/en/Pages/3/3010/pharmaceuticals#/en/Drugs/index/3/3974/lebanon-national-drug-index-lndi. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

Directorate General of Pharmaceutical Affairs and Drug Control, Ministry of Health, Sultanate of Oman. Price list last update 2-09-2018. https://www.moh.gov.om/documents/16539/1722100/PRICE+LIST+LAST+UPDATE+2-9-2018.pdf/c0f35c49-e5c8-4e0b-d37b-500f8be75fb4. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

Minisry of Public Health, State of Qatar. Registered pharmaceutical products list. https://www.moph.gov.qa/health-services/PublishingImages/Pages/pharmaceutical-products/List%20of%20Registered%20Pharmaceutical%20Products%20in%20Qatar.pdf. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

Saudi Food and Drug Authority. [List of prescribed pharmaceuticals and herbal preparations] [online database]. https://www.sfda.gov.sa/ar/drug/search/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed 27 Aug 2018.

Drug and Medical Devices Agency of Turkey (TİTCK). List of final licensed products. https://www.titck.gov.tr/PortalAdmin/Uploads/Titck/Dynamic/Nihai%20Ruhsatl%C4%B1%20%C3%9Cr%C3%BCnler%20Listesi%2017.08.2018.xlsx. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

Departmenf of Health-Abu Dhabi. HAAD approved drugs [online database]. https://www.haad.ae/haad/tabid/1328/Default.aspx. Accessed 21 Oct 2019.

Meintjes KF, Nolte AGW. Primary health care management challenges for childhood atopic eczema as experienced by the parents in a Gauteng district in South Africa [Meintjes and Nolte 2016, 21:315–322]. Health SA Gesondheid. 2016;21:315–22.

Yousuf MS. Managing childhood eczema in the Middle East. Wound Int. 2010;1:20–2.

Handa S, Jain N, Narang T. Cost of care of atopic dermatitis in India. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:213.

Lee BW, Detzel PR. Treatment of childhood atopic dermatitis and economic burden of illness in Asia Pacific countries. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66(Suppl 1):18–24.

Hasnain SM, Alqassim A, Hasnain S, Al-Frayh A. Emerging status of asthma, allergic rhinitis and eczema in the Middle East. J Dis Global Health. 2016;7:128–36.

Charrow A, Xia FD, Joyce C, Mostaghimi A. Diversity in dermatology clinical trials: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:193–8.

Hirano SA, Murray SB, Harvey VM. Reporting, representation, and subgroup analysis of race and ethnicity in published clinical trials of atopic dermatitis in the United States between 2000 and 2009. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:749–55.

Yeung CK, Ma KC, Chan HH. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus ointment monotherapy in chinese children with atopic dermatitis. Skinmed. 2006;5:12–7.

Chung BY, Kim HO, Kim JH, Cho SI, Lee CH, Park CW. The proactive treatment of atopic dermatitis with tacrolimus ointment in Korean patients: a comparative study between once-weekly and thrice-weekly applications. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:908–10.

Singalavanija S, Noppakun N, Limpongsanuruk W, et al. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus ointment in pediatric patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. J Med Assoc Thai. 2006;89:1915–22.

Rahman MF, Nandi AK, Kabir S, Kamal M, Basher MS, Banu LA. Topical tacrolimus versus hydrocortisone on atopic dermatitis in paediatric patients: a randomized controlled trial. Mymensingh Med J. 2015;24:457–63.

Goh CL, Lim JT, Leow YH, Ang CB, Kohar YM. The therapeutic efficacy of mometasone furoate cream 0.1% applied once daily vs clobetasol propionate cream 0.05% applied twice daily in chronic eczema. Singap Med J. 1999;40:341–4.

Kalariya M, Padhi BK, Chougule M, Misra A. Clobetasol propionate solid lipid nanoparticles cream for effective treatment of eczema: formulation and clinical implications. Indian J Exp Biol. 2005;43:233–40.

El-Khalawany MA, Hassan H, Shaaban D, Ghonaim N, Eassa B. Methotrexate versus cyclosporine in the treatment of severe atopic dermatitis in children: a multicenter experience from Egypt. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172:351–6.

Kim KH, Kono T. Overview of efficacy and safety of tacrolimus ointment in patients with atopic dermatitis in Asia and other areas. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1153–61.

Cheok S, Yee F, Song Ma JY, et al. Prevalence and descriptive epidemiology of atopic dermatitis and its impact on quality of life in Singapore. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:276–7.

Grills N, Grills C, Spelman T, et al. Prevalence survey of dermatological conditions in mountainous north India. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:579–87.

Weinberg J, Kaddu S, Gabler G, Kovarik C. The African teledermatology project: providing access to dermatologic care and education in sub-Saharan Africa. Pan Afr Med J. 2009;3:16.

Patro BK, Tripathy JP, De D, Sinha S, Singh A, Kanwar AJ. Diagnostic agreement between a primary care physician and a teledermatologist for common dermatological conditions in North India. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:21–6.

Seth D, Cheldize K, Brown D, Freeman EF. Global burden of skin disease: inequities and innovations. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2017;6:204–10.

Liang Y, Tian J, Shen CP, et al. Therapeutic patient education in children with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a multicenter randomized controlled trial in China. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:70–5.

Yoo JB, De Gagne JC, Jeong SS, Jeong CW. Effects of a hybrid education programme for Korean mothers of children with atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:329–34.

Park GY, Park HS, Cho S, Yoon HS. The effectiveness of tailored education on the usage of moisturizers in atopic dermatitis: a pilot study. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:360–2.

Son HK, Lim J. The effect of a web-based education programme (WBEP) on disease severity, quality of life and mothers’ self-efficacy in children with atopic dermatitis. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70:2326–38.

Futamura M, Masuko I, Hayashi K, Ohya Y, Ito K. Effects of a short-term parental education program on childhood atopic dermatitis: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:438–43.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding

This review and the Rapid Service Fee were funded by Pfizer Inc., New York, NY.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Editorial/medical writing support under the guidance of the authors was provided by Jennifer Jaworski, MS, at ApotheCom (San Francisco, CA, USA) and was funded by Pfizer Inc. (New York, NY, USA) in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:461–464).

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Yuri Igor Lopez Carrera has nothing to disclose. Anwar Al Hammadi is a consultant and advisory board member for Pfizer, AbbVie, Bioderma, Galderma, Janssen, Novartis, and Sanofi. Yu-Huei Huang has conducted clinical trials/served as principal investigator for Eli-Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, and Novartis; is an advisory board member for Pfizer, AbbVie, and Celgene; and is a speakers bureau member for AbbVie, Eli-Lilly, and Novartis. Lyndon John Llamado is a shareholder and employee of Pfizer Inc. Ehab Mahgoub is a shareholder and employee of Pfizer Inc. Anna M. Tallman was an employee of Pfizer Inc. at the time of initiation of this manuscript.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9918782.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lopez Carrera, Y.I., Al Hammadi, A., Huang, YH. et al. Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis in the Developing Countries of Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East: A Review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 9, 685–705 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-019-00332-3

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-019-00332-3