Abstract

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease with an increasing prevalence regionally and globally. It is characterized by intense itching and recurrent eczematous lesions. With the increase in the availability of treatment options for healthcare practitioner and patients, new challenges arise for treatment selection and approach. The current consensus statement has been developed to provide up-to-date evidence and evidence-based recommendations to guide dermatologists and healthcare professionals managing patients with AD in Saudi Arabia. By an initiative from the Ministry of Health (MOH), a multidisciplinary work group of 11 experts was convened to review and discuss aspects of AD management. Four consensus meetings were held on January 14, February 4, February 25, and March 18 of 2021. All consensus content was voted on by the work group, including diagnostic criteria, AD severity assessment, comorbidities, and therapeutic options for AD. Special consideration for the pediatric population, as well as women during pregnancy and lactation, was also discussed. The present consensus document will be updated as needed to incorporate new data or therapeutic agents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Following recent advances in therapeutic development and increase in the availability of treatment options for atopic dermatitis, new challenges arise for treatment selection and approach |

The aim of this article is to provide up-to-date evidence and evidence-based recommendations to guide dermatologists and healthcare professionals managing patients with atopic dermatitis in Saudi Arabia |

The consensus development process was undertaken by a multidisciplinary work group of 11 experts, including six dermatologists and five pharmacists |

Treatment goal of atopic dermatitis: EASI ≥ 75 response and NRS (< 4) or DLQI ≤ 5 |

Introduction

Background and Definition

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory dermatological disease affecting around a quarter of the pediatric population and 5–10% of adults worldwide [1,2,3,4]. The prevalence rates of AD among adults in different provinces of Saudi Arabia ranges from 6% to 13% [5]. Characterized by severe itching and recurrent eczematous lesions, its pathogenesis combines genetic susceptibility, skin barrier dysfunction, and immune dysregulation [6,7,8,9]. The clinical manifestations of AD vary with age, where area of involvement is the main differentiating factor. In infants (less than 2 years of age), lesions usually emerge on the cheek, forehead, scalp, neck, trunk, and extensor (outer) surfaces of the extremities. In children (2–12 years), adolescence, and adulthood, the flexural surfaces of the extremities are frequently affected [10].

Purpose, Aim, and Scope

The management of AD encompasses various factors and can be variable between healthcare providers in daily clinical practice. As a result of the heterogeneity of the disease and regional treatment accessibility, notable diversity exists across international guidelines regarding the recommendations for the management of AD. With this in mind and following recent advances in therapeutic development and evidence-based recommendations, the current consensus recommendations were developed to provide guidance to dermatologists and healthcare workers, allowing them to ensure safe and satisfactory management of AD for their patients in Saudi Arabia. Topics reviewed in this document include diagnostic criteria, AD severity assessment, comorbidities, and treatment options. Special considerations for the management of AD in the pediatric population, as well as women during pregnancy and lactation, and vaccination in patients with AD were also discussed. These recommendations are intended to support rather than replace physician’s clinical judgement.

Disclaimer on the Use of Clinical Practice Guidelines

Clinical practice guidelines are based on the best information available at the time of writing and are to be updated regularly. They are evidence-based tools for guiding physicians managing health conditions. They are not fixed protocols and strict treatment guidelines that must be followed but are only tools to help manage AD patients. Decisions pertaining to treatment must be taken on a case-by-case basis tailoring the treatment regimen to patients’ personal circumstances and medical history. Physicians are advised to consult approved product monographs in their institution’s formulary. These formularies include drug dosage, special warnings precautions for use, contraindications, and side effects. Physicians should consider institutional formulruy restrictions when selecting treatment options.

Target Population, Audience/End Users

The target population for the present consensus document is pediatric and adult people with AD. The targeted audience/end users are general dermatologists and other healthcare providers who encounter patients with AD in secondary and tertiary care settings.

Methods

A multidisciplinary work group of 11 experts, including six dermatologists and five pharmacists, was chosen on the basis of their experience in treating AD. One method expert was invited and consulted throughout the process of developing the consensus recommendations. The Saudi Ministry of Health (MOH) oversaw and supported the process. Four consensus meetings were held on January 14, February 4, February 25, and March 18 of 2021.

During the first meeting, the work group defined the objectives, scope, target population, and target audience of the consensus statements. The work group identified four main topics of interest, which would serve as the sections for review: (1) diagnostic criteria, (2) AD severity assessment, (3) evaluation and treatment of comorbidities, (4) management of AD and treatment options. Work group members were assigned to one of these four workstreams depending on their interest and expertise and developed content for the document within their respective sections.

The work group identified seven international guidelines for AD management that served as the basis for the generation of the current guidelines: the 2017 and 2020 European guidelines, the 2017 and 2020 Japanese guidelines, the 2014 and 2017 American guidelines, and the 2019 Indian guidelines [3, 7, 11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. The literature review and reference lists from the identified guidelines and consensus statements were then evaluated to locate additional articles.

A draft of the developed content was circulated among group members prior to the second and third meetings. During the meetings, consensus was reached using the nominal group technique after thorough discussions. All work group members had the right to vote on the recommendations. When agreement was achieved by at least 75% of the voting experts, the statement was considered consented, but strength of recommendation was not addressed.

All the consented recommendations were shared with the MOH and work group experts for any further input. A final workshop for the work group was then held in March 2021 to discuss the additional input for further agreement. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Diagnostic Criteria

AD is a clinical diagnosis based on characteristics of morphology, age-dependent distribution, and associated clinical signs. Various criteria for diagnosis have been proposed over the years to maximize the accuracy of diagnosis. We recommend using the criteria developed by the American Academy of Dermatology for definite diagnosis (Table 1) [3].

Atopic Dermatitis Severity Assessment

Defining and assessing disease severity is essential in directing treatment choices in AD. Because there are no serologic markers that precisely reflect AD, measurement of severity is primarily based on signs and symptoms. Several physician- and patient-rated severity assessment tools are available, varying considerably with respect to content, scale, instructions, validity, and concordance. These include the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index, the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), Physician Global Assessment (PGA), body surface area (BSA), Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and pruritis Numerical Rating Scale (NRS).

In terms of the practical applications of these assessment tools, we recommend using PGA, EASI, pruritus NRS, and DLQI, as they are practical tools for use in routine clinical practice, widely recognized by local health authorities, and capture the essential elements of the disease.

Comorbidities of Atopic Dermatitis

AD is associated with multiple atopic and nonatopic comorbidities [18]. There is a bidirectional and multifactorial relationship between AD and these comorbidities. Some of these comorbidities could be secondary to the burden of chronic AD or distinct pathomechanisms triggered by AD. To improve outcomes and clinical decision-making for patients with AD, important consideration must be given to comorbidities [18].

Atopic Comorbidities

According to the American Academy of Dermatology, atopic comorbidities like asthma, allergic rhinitis/rhinoconjunctivitis, and food allergy are diagnostic criteria for AD [3]. However, there is some controversy regarding the mechanisms and epidemiology of these comorbidities in AD [18]. Studies have shown that AD was statistically significantly associated with a higher prevalence of these atopic comorbidities in comparison to population-based controls without AD [19]. Among children with more severe AD, the severity and prevalence of these comorbidities are greater [20]. Asthma prevalence increases with worsening AD [21]. While AD severity is the strongest predictor, other characteristics were found to be related to atopic comorbidities in adult patients with AD [22].

In addition to that, eosinophilic esophagitis (EOE), which is a rare disease, is more prevalent in AD and is recognized as a comorbidity of AD [23].

The progression of atopic disorders, from eczema in infants and toddlers to allergic rhinitis and finally to asthma in older toddlers and children, is referred to by the term “atopic march” [24]. EOE has been recently recognized as a late manifestation of the atopic march in pediatric patients [24, 25]. These conditions seem to be interconnected. Nevertheless, their relationship is still not thoroughly explored and is less likely to be that of progression particularly because of the different genetic and environmental factors playing a role in the atopic march [26].

Developing different atopic comorbidities in younger children with AD was found to be associated with disease severity, age at onset, atopic history in parents, filaggrin (FLG) mutations, polysensitization, and nonrural environment [27].

Other Comorbidities

Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) may be more common in patients with AD than in the general population [28, 29]. Secondary to barrier disruption, patients with AD have greater absorption of irritants and allergens through the skin. This leads to immune activation and ultimately contact sensitization [29,30,31,32,33]. Patients with AD regularly use topical corticosteroids and emollients that contain contact sensitizers like propylene glycol and sorbitan [29, 33,34,35,36]. Avoidance of contact allergen and confirming the diagnosis with patch testing are advised in selected cases [37].

Behavioral and Mental Health Conditions

Intense pruritus, high sleep disturbance rates, stigma, social isolation, poor quality of life (QoL), and neuro-inflammation have been postulated to contribute to increased anxiety, depression, suicidality, or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in AD [18]. Depression was usually present in moderate-to-severe AD with depressive symptoms directly correlated with disease severity and modifiable with improved AD treatments [38].

Infections

AD is frequently complicated by cutaneous and extracutaneous infections. Cutaneous infections are related to immune dysregulation, skin-barrier dysfunction, lower antimicrobial peptides, increased bacterial colonization, and use of immunosuppressive medications [39]. Studies have found that 70% of patients with AD were colonized with Staphylococcus aureus on lesional skin, 39% on the non-lesional skin, and 62% in the nose [40]. Systemic antibiotics should only be used if skin is clinically infected, and not because there is a positive culture of S. aureus [40]. In severe disease, there are strong correlations between AD and eczema herpeticum (EH) [41].

AD is also associated with a higher risk of extracutaneous infections, such as upper respiratory tract infections, pneumonia, recurrent ear infections, sinus infections, gastroenteritis, urinary tract infections, and higher usage of antibiotics in children with AD compared with healthy controls [42, 43]. Consider infection risk in clinical decision-making for patients with AD. For example, a history of recurrent infections may raise suspicion for an underlying immune deficiency [39, 44].

Cardiometabolic Comorbidities

AD is associated with a greater risk of cardiovascular disease and events, particularly in severe AD. There are multiple potential risk factors for cardiometabolic disease among patients with AD, including sleep disturbance [43, 45], sedentary lifestyle [46], obesity, higher rates of cigarette smoking [47], and side effects from some systemic medications (e.g., corticosteroids and cyclosporine A).

Patients with AD are at higher risk of suffering from hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart attack, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular diseases, and stroke [48].

Management of Atopic Dermatitis

Eligibility Criteria for Systemic/Biologic Treatment

Systemic treatments are generally indicated in moderate-to-severe AD. Based on the recommended clinical scoring tools, at least one of the following criteria can be used to define moderate-to-severe AD and are considered as appropriate criteria for initiating systemic therapy [15, 49,50,51,52]:

-

1.

EASI ≥ 16

-

2.

DLQI score ≥ 10

-

3.

Pruritus NRS ≥ 4

-

4.

PGA ≥ 3

-

5.

BSA score ≥ 10%

Atopic Dermatitis Treatment Goals

In general, the goal of treatment is to decrease skin inflammation and pruritus, restore skin barrier function, and enhance QoL. It is advisable to define goals of treatment for every patient ahead of initiating treatment. EASI, PGA, DLQI, and NRS are recommended for use in daily practice to establish and monitor the achievement of treatment goals and guide therapy (Fig. 1). We recommend that both the following criteria should be achieved for the treatment goal of AD within 16 weeks [7, 49]:

-

1.

EASI ≥ 75 response

-

2.

NRS (< 4) or DLQI ≤ 5

For Saudi MOH regulatory requirements and for the purposes of payer reimbursement, the EASI tool is required.

Patient Education

Educating patients and caregivers in AD has proved to increase adherence to treatment, promote better outcomes, and improve QoL [53,54,55]. Different educational programs have been studied, and their structure depends on the social and economic conditions [56]. However, the main principles of these programs revolve around the following:

Emollients

In AD, the function of the skin barrier including moisturizing factors is impaired, leading to invasion of allergens which trigger dermatitis flares. Topical moisturizers suppress itching and help in maintaining skin barrier function [57].

As a result of the risk of contact allergies, emollients with the least number of ingredients are recommended. Fragrances and preservatives which may contain known allergens should be especially avoided [58]. Special consideration should be given to emollients containing allergic plant proteins from peanut, oat, or wheat and must be avoided in children less than 2 years of age [59].

Liberal amounts of emollients should be applied. Moisturizing twice-daily (morning and evening) and after bathing (soak and seal technique) are the most effective [7, 15].

Continuous usage of moisturizing products after dermatitis remission with topical anti-inflammatory drugs is evident for maintaining the remission [60].

Cleansing

In AD, adhesion of body fluid (sweat), topical drugs, sebum, and bacterial contaminants may have a role in exacerbating the diseases. Keeping the skin clean is essential in maintaining the physiologic properties of the skin. However, this should be done with low-irritant, nonallergenic formulas with the least additives like pigment and perfumes and should be rinsed thoroughly to protect the skin from irritation [7, 15].

The frequency of showering showed no difference between twice weekly or every day in a small, randomized study as long as the skin’s hydration is managed after the bath [61]. However, prolonged showers should be avoided as they are associated with worsening of symptoms [62]. Water temperature should be set between 37 and 38 °C as this is the optimum temperature for skin barrier recovery, and higher temperatures induce itching response [63,64,65].

Intermittent use of antiseptic baths can be considered in patients with recurrent skin infections. An example is the addition of one-quarter to one-half cup of 6% household bleach in a bathtub full of water (40 gallons) [66]

Aggravating Factors

It is fundamental to educate patients and families about exacerbating factors; these may include:

Nonspecific Irritation

Contact with sweat, saliva, hair, and friction against clothes may exacerbate AD symptoms. Appropriate measures should be taken to avoid nonspecific irritation. For example, sweat and saliva should be washed or wiped away, nonirritating clothing should be chosen (rough textured clothes like wool must be avoided), and hair should be tied up to reduce itching [15].

Scratching is also an important exacerbating factor. In addition to therapeutic measures to control pruritus, education about cutting nails short, wearing long sleeves and long pants may reduce scratching practices [15].

Contact Allergy

Progression of AD can be caused by contact with cosmetics, perfumes, metals, topical drugs, plants, and skin and hair care products. Suspicion of contact allergy should be raised in cases where AD onset and worsening has occurred recently with limited response to treatment or with atypical eczema distribution [37].

Food Allergen

Associated food allergy is present in one-third of children with moderate-to-severe AD [67]. Among infants and toddlers, risk of AD exacerbation is higher with Cow’s milk, hen’s egg, wheat, soya, tree nut, and peanuts. On the other hand, in older children and adults, pollen-related food allergens are mostly associated with AD exacerbations [68]. Food elimination should be undertaken only when there is clear evidence of food allergy as this can affect child development. When suspecting food allergy, referral to allergist-immunologist should be considered.

Aeroallergen

Aeroallergens (mites, house dust, pollen, pet hair) are relevant trigger factors for AD diagnostic workup includes skin prick tests or serum Immunoglobulin E antibody tests. Conversely, both methods have a low predictive value. Avoidance of aeroallergen should be based on careful evaluation of any changes in eruption features or environmental factors. Due consideration should be given for the individual’s medical history and results of elimination and challenge tests [15].

Pharmacologic Therapies

Topical Therapies

Topical Anti-inflammatory Therapies

Topical corticosteroids (TCSs) are considered the mainstay of AD therapy and have been used for decades. They are used as a first-line anti-inflammatory treatment option in AD. TCSs are classified into four classes according to their potency (Table 2) [17].

The potency and vehicle of the TCSs should be tailored on the basis of consideration of different factors, including the patient age, body area involved, disease severity, and treatment duration [69]. Twice-daily application of TCSs is advised for AD treatment. Clinical trials have shown that TCSs are safe and effective for treating AD flare-ups when used for up to 4 weeks [70]. However, many flare-ups may be adequately controlled with a shorter treatment course (1–2 weeks) [71]. In clinical practice, other medications are used in combination with TCS.

For maintenance therapy, TCSs and emollients should be used proactively (e.g., intermittent, or twice-weekly dosing) for up to 16 weeks and are effective in reducing the risk of flares [72, 73]. Cutaneous and systemic side effects can occur, particularly with very potent and potent TCS (classes I and II) [74]. Patients using TCS over the long-term should be monitored by regular physical examinations to monitor for cutaneous side effects [75]. Very potent TCS (class I) are not recommended for AD treatment, especially in children.

Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) (tacrolimus and pimecrolimus) are indicated as second-line anti-inflammatory treatment option for moderate-to-severe AD (tacrolimus) and in mild-to-moderate AD (pimecrolimus) in adults and children at least 2 years of age when other topical therapies are inadequate or inadvisable [76, 77]. They can be used off-label as first-line therapy in selected cases, particularly in sensitive skin areas, and in patients receiving long-term therapy [7]. TCSs can be combined with TCI for the treatment of AD [7].

Proactive, intermittent therapy with tacrolimus twice weekly for up to 52 weeks is effective in preventing, delaying, and reducing the occurrence of flares, thus improving QoL for patients with AD [78, 79].

Transient burning or stinging sensation is common when using TCIs and may be associated with the initial application and improve with continued use (Table 3) [76, 77].

Topical Phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) Inhibitors

Crisaborole is indicated for the treatment of mild-to-moderate AD in adults and pediatric patients 3 months or older [80]. It inhibits PDE4, resulting in an increase in intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate, which causes reduction in pruritogenic cytokines production [80, 81]. On the basis of two pivotal phase III clinical trials done on patients aged 2 years or older, as compared with vehicle only, crisaborole significantly increased Investigator’s Static Global Assessment score of clear or almost transparent with a two-grade or more remarkable improvement from baseline and improved all signs of AD like erythema, exudation, excoriation, induration, and lichenification [81] (Table 3).

Novel Topical Therapies

Delgocitinib ointment is a topical JAK (Janus kinase) inhibitor approved in Japan for treating adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD for up to 28 weeks, and other topical JAK inhibitors (topical tofacitinib and ruxolitinib) seem to be promising treatments for mild-to-moderate AD in a phase II, randomized trial [82].

Phototherapy

Phototherapy is an adjuvant skin-directed therapy, thus reducing sleep disturbances in patients with AD [83]. It is considered, with concomitant topical anti-inflammatory therapies, as an acceptable treatment choice for moderate-to-severe AD, if available. It can also be used as monotherapy for patients in whom topical anti-inflammatory therapies are not appropriate (i.e., adverse reaction, contraindication) [84].

Ultraviolet A1 (UVA1) and narrow-band ultraviolet B (NB-UVB) are the most appropriate phototherapy options for AD treatment [84]. Actinic damage, local erythema and tenderness, pruritus, burning, and stinging are common adverse events of phototherapy [85,86,87].

In practice, phototherapy’s limitations are accessibility, feasibility, and lack of efficacy on lesions on the scalp and folds. Concomitant treatment with topical anti-inflammatory drugs, emollients, and phototherapy are appropriate options to decrease the frequency of flare-ups [13, 88].

Systemic Therapies

If AD cannot be controlled adequately with appropriate topical treatments and phototherapy, systemic therapy is recommended. It is helpful in patients who usually require potent TCS for large body areas over extended periods of time. Systemic treatment options for AD include systemic corticosteroids, cyclosporine A (CsA), azathioprine (AZA), mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), and methotrexate (MTX) (Tables 4, 5).

Systemic corticosteroids: long-term systemic steroid should be avoided. However, it can be used for short courses to treat an acute exacerbation. Moreover, risk of a flare-up with discontinuation of the systemic steroid should be considered [14, 15, 89].

CsA is an oral calcineurin inhibitor used for moderate-to-severe AD. It is licensed for the AD treatment in adults in many European countries and may be used off-label in children and adolescent patients with a refractory or severe disease. The treatment duration could vary between 3 months and 1 year. Nevertheless, longer durations of low-dose CsA could be tolerated in some patients [7] (Tables 4, 5).

MTX is an immunosuppressive agent that is frequently used off-label to treat moderate-to-severe AD [14, 90]. Methotrexate has a slow onset of action, and its maximum effect is reached after 8–12 weeks of treatment [91, 92]. Other immunosuppressants including AZA and MMF can be used for moderate-to-severe AD treatment [14, 93,94,95,96] (Tables 4, 5).

In 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) and Saudi Food and Drug Authority (SFDA) approved dupilumab as the first biologic for patients with moderate-to-severe AD who are not optimally responsive to topical therapies or when those therapies are inadvisable or treatment failure on one or more oral immunosuppressive drugs in patients 6 years or older [97, 98].

Dupilumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody directed against the interleukin (IL)-4a receptor alpha-subunit. It works by blocking the signaling of two key drivers of type 2 immune response, namely IL-4 and IL-13 [97, 98].

Dupilumab should be combined with daily emollients with or without topical anti-inflammatory drugs as needed. Until the full clinical outcome is achieved, conventional systematic immunosuppressants could be continued during the first few weeks of initiating dupilumab [97, 98] (Table 6).

Combining dupilumab with a conventional drug or phototherapy is an appropriate and safe therapy option which allows patients recalcitrant to dupilumab monotherapy [99]. Subsequent real-life studies have confirmed the data from the registration studies in clinical practice, regarding efficacy, safety, and improvement of patient-reported outcomes [100, 101]

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) and SFDA approved baricitinib and upadacitinib (JAK inhibitors) to treat moderate-to-severe AD in adult patients who are candidates for systemic therapy [102,103,104,105,106]. On the other hand, USFDA and SFDA approved upadacitinib to treat moderate-to-severe AD in pediatric patients at least 12 years of age and adults, and abrocitinib for adults only [104, 107] (Table 6). Tralokinumab is another fully human monoclonal anti-IL-13 antibody recently approved by the USFDA and EMA for treating moderate-to-severe AD that is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies for adults. It is not yet approved by the SFDA.

New Treatment in the Pipeline

Monoclonal antibodies that inhibit the effects of various interleukins (i.e., IL-4, IL13, IL-5, IL-17, IL-22, IL-31, IL-33) show therapeutic promise for the treatment of AD such as nemolizumab, lebrikizumab, and fezakinumab [108].

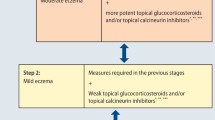

Treatment Algorithm

The treatment algorithm for AD is shown in Fig. 2. Patients who fail first-line therapy or who have contraindications to these therapies are candidates for systemic therapies. Treatment failure may be considered as an inadequate response after 4–8 weeks of appropriate topical therapy with or without 12–16 weeks of phototherapy. Availability, suitability, and compliance to phototherapy should be considered [52, 71].

General response to most systemic therapies should be evaluated after 12 weeks, except for cyclosporine, where the response should be evaluated after 6 weeks. Dose optimization or switching should be considered if there is no improvement [71].

Reconsider diagnosis of AD for refractory cases/persistent cases despite optimum therapy.

Most of the guidelines do not prefer one systemic therapy over another. However, cost and safety should be taken into consideration [51].

Referral of Patients with Atopic Dermatitis

Most patients with AD are responsive to dedicated conservative treatment. We recommend referral to a dermatologist in the following indications [109, 110]:

-

1.

Same day referral

-

2.

Suspicion of eczema herpeticum—urgent referral, ideally within 1–2 weeks

-

Severe AD irresponsive to optimal topical therapy is seen after 2–4 weeks

-

If treatment of bacterial-infected AD has failed

-

-

3.

Routine (non-urgent) referral (ideally, every patient shall be seen within 1–4 weeks; however, it might take longer)

-

Diagnosis is uncertain.

-

Partially responded AD to the appropriate treatment and duration.

-

AD on face/genitalia/palms and soles which is suboptimally controlled or affecting the patient’s QoL.

-

AD with history of severe and recurrent infections.

-

Contact allergic dermatitis is suspected.

-

Uncontrolled or poorly controlled AD subjectively.

-

AD responsive to optimal management but with non-enhancing QoL and psychosocial well-being must be referred for psychological advice.

-

Moderate or severe AD with suspected food allergy must be referred for specialist investigation and management of the AD and allergy.

-

As reflected by local growth charts, children with AD who exemplify failure to thrive at normal growth rates must be referred to specialists.

-

Special Patient Populations

Specific Considerations for Children

Treatment in the pediatric population should take into consideration factors related to the patient, disease, and treatment. It considers several factors such as a less experienced immune system, an incomplete skin barrier, and a larger surface area-to-body weight ratio, which can result in an up to 2.7 times greater systemic exposure and risk of intoxication [7].

Pharmacologic Therapies

The pharmacologic therapy for pediatrics is topical therapy using TCS, TCI, and/or PDE4 inhibitors (crisaborole). The principles of topical therapy are the same as in adults but are adapted with respect to increased immersion and altered surface-to-body weight ratio. Using less potent TCS (classes III and IV) in pediatrics is recommended, especially for sensitive areas such as the diaper area, face, and scalp. On the basis of safety data, TCIs are recommended as a steroid-sparing agent. They are approved for topical treatment for pediatric patients at least 2 years of age. It is also appropriate to use off-label TCIs in pediatric patients younger than 2 years of age [7, 13, 111, 112]. Crisaborole is indicated for topical treatment of mild-to-moderate AD in pediatric patients at least 3 months of age [80].

Phototherapy may be considered with precautions for children because of practical challenges, long-term concerns, and limited data on its use in pediatric AD [7]

Several systemic therapies are used to treat moderate-to-severe pediatric AD refractory to topical therapy and/or phototherapy. They include MTX, CsA, AZA, MMF, systemic corticosteroids (SCS), and dupilumab as the only biologic approved for use in patients 6 years or older.

We recommend physicians to be diligently cautious with regards to safety, tolerability, and allergenic profiles when treating children younger than 2 years of age. Systemic treatment should be introduced by qualified specialists only.

Specific Considerations During Preconception, Pregnancy, and Lactation

Pharmacologic Therapies

The first-line pharmacologic therapy for AD during pregnancy and lactation are TCSs, as they are considered safe. Although prolonged use of high doses of higher-ranked topical steroids (300 g or more) has been reported to be associated with low birth weight in few cases, this is unlikely with appropriate use. Local side effects such as risk of striae may occur when using potent TCS on the abdomen and thighs [113].

Off-label use of TCIs (specifically tacrolimus) during pregnancy may be considered appropriate [113].

Phototherapy is considered a safe option for pregnancy. Supplementation of folic acid should be considered [113].

In moderate-to-severe AD during pregnancy which is refractory to topical therapy and/or phototherapy, the benefit of using systemic therapies must considered in the light of patient characteristics and any potential or actual risk. Short-term SCS and CyA are considered relatively safe with close monitoring. Continuation of AZA treatment (halved dose) is considered possible on strict indication, while MTX and MMF are strictly contraindicated in pregnancy [7]. The decision to initiate systemic therapies for pregnant or lactating women should be taken in collaboration with obstetricians. Both male and female patients with AD who want to pursue a family life require special considerations to ensure treatment safety and efficacy.

Vaccination

Common childhood immunizations in the first year are not associated with an increased risk of more severe AD or allergic sensitization [7]. Vaccinations, including the measles vaccine, are generally safe in hen’s egg-allergic patients with AD [7]. Vaccinations against varicella are recommended to avoid severe cutaneous viral infections.

Parents of atopic children should be encouraged to fully vaccinate their children [7].

Currently, there is no evidence suggesting that AD is an independent risk factor for acquiring COVID-19 or suffering from a more severe course [114]. AD is not a contraindication to vaccination.

Because the vaccination response is mainly T helper cell 1 skewed, it is unclear if COVID-19 vaccination could cause worsening AD [114]. Systemic immunosuppressants and JAK inhibitors are used for AD treatment and may attenuate the vaccination response, but no attenuation was observed with dupilumab [114].

Conclusion

General dermatologists and other healthcare providers frequently encounter AD in their patient populations. Optimal AD management requires thorough understanding of disease pathogenesis and treatment strategies. This document serves as a platform to enhance clinical practice parameters to meet every patient’s treatment goals. Consequently, an individualized management plan should always be considered in order to provide best treatment for patients with AD.

References

Ng YT, Chew FT. A systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors associated with atopic dermatitis in Asia. World Allergy Organ J. 2020;13(11): 100477.

Barbarot S, Auziere S, Gadkari A, et al. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in adults: results from an international survey. Allergy. 2018;73(6):1284–93.

Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(2):338–51.

Nutten S. Atopic dermatitis: global epidemiology and risk factors. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66(Suppl 1):8–16.

Alqahtani JM. Atopy and allergic diseases among Saudi young adults: a cross-sectional study. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(1):0300060519899760.

Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2016;387(10023):1109–22.

Wollenberg A, Christen-Zäch S, Taieb A, et al. ETFAD/EADV Eczema task force 2020 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults and children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(12):2717–44.

Czarnowicki T, Krueger J, Guttman-Yassky E. Skin barrier and immune dysregulation in atopic dermatitis: an evolving story with important clinical implications. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2:371–9.

Kim J, Kim BE, Leung DYM. Pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis: clinical implications. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2019;40(2):84–92.

Kapur S, Watson W, Carr S. Atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2018;14(Suppl 2):52.

Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(2):327–49.

Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. Management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(1):116–32.

Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(5):657–82.

Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(6):850–78.

Katoh N, Ohya Y, Ikeda M, et al. Japanese guidelines for atopic dermatitis 2020. Allergol Int. 2020;69(3):356–69.

Katayama I, Aihara M, Ohya Y, et al. Japanese guidelines for atopic dermatitis 2017. Allergol Int. 2017;66(2):230–47.

Rajagopalan M, De A, Godse K, et al. Guidelines on management of atopic dermatitis in India: an evidence-based review and an expert consensus. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;64(3):166–81.

Silverberg JI. Comorbidities and the impact of atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123(2):144–51.

Hua T, Silverberg JI. Atopic dermatitis in US adults: epidemiology, association with marital status, and atopy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121(5):622–4.

Silverberg JI, Simpson EL. Associations of childhood eczema severity: a US population-based study. Dermatitis 2014;25(3):107–14.

Vakharia PP, Chopra R, Sacotte R, et al. Validation of patient-reported global severity of atopic dermatitis in adults. Allergy. 2018;73(2):451–8.

Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ, et al. Association of atopic dermatitis with allergic, autoimmune, and cardiovascular comorbidities in US adults. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121(5):604-612.e3.

González-Cervera J, Arias Á, Redondo-González O, et al. Association between atopic manifestations and eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;118(5):582-590.e2.

Belgrave DC, Simpson A, Buchan IE, et al. Atopic dermatitis and respiratory allergy: what is the link. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2015;4(4):221–7.

Hill DA, Grundmeier RW, Ramos M, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis is a late manifestation of the allergic march. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(5):1528–33.

Ker J, Hartert TV. The atopic march: what’s the evidence? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;103(4):282–9.

Paller AS, Spergel JM, Mina-Osorio P, et al. The atopic march and atopic multimorbidity: many trajectories, many pathways. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(1):46–55.

Simonsen AB, Johansen JD, Deleuran M, et al. Contact allergy in children with atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(2):395–405.

Owen JL, Vakharia PP, Silverberg JI. The role and diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19(3):293–302.

Jakasa I, de Jongh CM, Verberk MM, et al. Percutaneous penetration of sodium lauryl sulphate is increased in uninvolved skin of patients with atopic dermatitis compared with control subjects. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(1):104–9.

Thyssen JP, Kezic S. Causes of epidermal filaggrin reduction and their role in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(4):792–9.

Halling-Overgaard AS, Kezic S, Jakasa I, et al. Skin absorption through atopic dermatitis skin: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(1):84–106.

Hamann CR, Bernard S, Hamann D, et al. Is there a risk using hypoallergenic cosmetic pediatric products in the United States? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(4):1070–1.

Mailhol C, Lauwers-Cances V, Rancé F, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for allergic contact dermatitis to topical treatment in atopic dermatitis: a study in 641 children. Allergy. 2009;64(5):801–6.

Brar KK, Leung DYM. Eczema complicated by allergic contact dermatitis to topical medications and excipients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;120(6):599–602.

Rastogi S, Patel KR, Singam V, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to personal care products and topical medications in adults with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(6):1028-1033.e6.

Tamagawa-Mineoka R, Masuda K, Ueda S, et al. Contact sensitivity in patients with recalcitrant atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol. 2015;42(7):720–2.

Patel KR, Immaneni S, Singam V, et al. Association between atopic dermatitis, depression, and suicidal ideation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(2):402–10.

Sun D, Ong PY. Infectious complications in atopic dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2017;37(1):75–93.

Bjerre RD, Bandier J, Skov L, et al. The role of the skin microbiome in atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(5):1272–8.

Leung DY. Why is eczema herpeticum unexpectedly rare? Antiviral Res. 2013;98(2):153–7.

Böhme M, Lannerö E, Wickman M, et al. Atopic dermatitis and concomitant disease patterns in children up to two years of age. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82(2):98–103.

Silverberg JI, Garg NK, Paller AS, et al. Sleep disturbances in adults with eczema are associated with impaired overall health: a US population-based study. J Investig Dermatol. 2015;135(1):56–66.

Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Childhood atopic dermatitis and warts are associated with increased risk of infection: a US population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(4):1041–7.

Yu SH, Attarian H, Zee P, et al. Burden of sleep and fatigue in US adults with atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis 2016;27(2):50–8.

Strom MA, Silverberg JI. Associations of physical activity and sedentary behavior with atopic disease in United States children. J Pediatr. 2016;174:247-253.e3.

Kantor R, Kim A, Thyssen JP, et al. Association of atopic dermatitis with smoking: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(6):1119-1125.e1.

Silverberg JI. Association between adult atopic dermatitis, cardiovascular disease, and increased heart attacks in three population-based studies. Allergy. 2015;70(10):1300–8.

Hong CH, Gooderham MJ, Albrecht L, et al. Approach to the assessment and management of adult patients with atopic dermatitis: a consensus document. Section V: consensus statements on the assessment and management of adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22(1_suppl):30s–5s.

Damiani G, Calzavara-Pinton P, Stingeni L, et al. Italian guidelines for therapy of atopic dermatitis-Adapted from consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis). Dermatol Ther. 2019;32(6): e13121.

Chan TC, Wu NL, Wong LS, et al. Taiwanese Dermatological Association consensus for the management of atopic dermatitis: a 2020 update. J Formos Med Assoc. 2021;120(1 Pt 2):429–42.

Lynde CW, Bourcier M, Gooderham M, et al. A treatment algorithm for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adults. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22(1):78–83.

Mancini AJ, Paller AS, Simpson EL, et al. Improving the patient-clinician and parent-clinician partnership in atopic dermatitis management. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2012;31(3 Suppl):S23–8.

Ahrens B, Staab D. Extended implementation of educational programs for atopic dermatitis in childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2015;26(3):190–6.

Rea CJ, Tran KD, Jorina M, et al. Associations of eczema severity and parent knowledge with child quality of life in a pediatric primary care population. Clin Pediatr. 2018;57(13):1506–14.

Stalder JF, Bernier C, Ball A, et al. Therapeutic patient education in atopic dermatitis: worldwide experiences. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30(3):329–34.

van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Christensen R, et al. Emollients and moisturisers for eczema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2(2): Cd012119.

Dinkloh A, Worm M, Geier J, et al. Contact sensitization in patients with suspected cosmetic intolerance: results of the IVDK 2006–2011. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(6):1071–81.

Wollenberg A, Fölster-Holst R, Saint Aroman M, et al. Effects of a protein-free oat plantlet extract on microinflammation and skin barrier function in atopic dermatitis patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(Suppl 1):1–15.

Werner Y, Lindberg M. Transepidermal water loss in dry and clinically normal skin in patients with atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1985;65(2):102–5.

Koutroulis I, Petrova K, Kratimenos P, et al. Frequency of bathing in the management of atopic dermatitis: to bathe or not to bathe? Clin Pediatr. 2014;53(7):677–81.

Koutroulis I, Pyle T, Kopylov D, et al. The association between bathing habits and severity of atopic dermatitis in children. Clin Pediatr. 2016;55(2):176–81.

Denda M, Sokabe T, Fukumi-Tominaga T, et al. Effects of skin surface temperature on epidermal permeability barrier homeostasis. J Investig Dermatol. 2007;127(3):654–9.

Murota H, Izumi M, Abd El-Latif MI, et al. Artemin causes hypersensitivity to warm sensation, mimicking warmth-provoked pruritus in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(3):671-682.e4.

Nowicki R, Trzeciak M, Wilkowska A, et al. Atopic dermatitis: current treatment guidelines. Statement of the experts of the Dermatological Section, Polish Society of Allergology, and the Allergology Section, Polish Society of Dermatology. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2015;32(4):239–49.

Sawada Y, Tong Y, Barangi M, et al. Dilute bleach baths used for treatment of atopic dermatitis are not antimicrobial in vitro. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(5):1946–8.

Wassmann A, Werfel T. Atopic eczema and food allergy. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2015;101:181–90.

Wassmann-Otto A, Heratizadeh A, Wichmann K, et al. Birch pollen-related foods can cause late eczematous reactions in patients with atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2018;73(10):2046–54.

Berke R, Singh A, Guralnick M. Atopic dermatitis: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(1):35–42.

Buys LM. Treatment options for atopic dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(4):523–8.

Smith S, Baker C, Gebauer K, et al. Atopic dermatitis in adults: an Australian management consensus. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61(1):23–32.

Cury Martins J, Martins C, Aoki V, et al. Topical tacrolimus for atopic dermatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(7): Cd009864.

Reitamo S, Rustin M, Ruzicka T, et al. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus ointment compared with that of hydrocortisone butyrate ointment in adult patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109(3):547–55.

Rathi SK, D’Souza P. Rational and ethical use of topical corticosteroids based on safety and efficacy. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57(4):251–9.

Charman CR, Morris AD, Williams HC. Topical corticosteroid phobia in patients with atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142(5):931–6.

Product Information: Elidel®, pimecrolimus topical cream 1%. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp., East Hanover; 2006.

Product Information: PROTOPIC® topical ointment, tacrolimus 0.03% topical ointment, 0.1% topical ointment. Astellas Pharma US, Inc. (per FDA), Deerfield; 2011.

Thaçi D, Reitamo S, Gonzalez Ensenat MA, et al. Proactive disease management with 0.03% tacrolimus ointment for children with atopic dermatitis: results of a randomized, multicentre, comparative study. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(6):1348–56.

Wollenberg A, Reitamo S, Atzori F, et al. Proactive treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults with 0.1% tacrolimus ointment. Allergy. 2008;63(6):742–50.

Product Information: EUCRISA™ topical ointment, crisaborole topical ointment. Pfizer Labs (per FDA), New York; 2020.

Paller AS, Tom WL, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel, nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor for the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD) in children and adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(3):494-503.e6.

Bissonnette R, Papp KA, Poulin Y, et al. Topical tofacitinib for atopic dermatitis: a phase IIa randomized trial. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(5):902–11.

Garritsen FM, Brouwer MW, Limpens J, et al. Photo(chemo)therapy in the management of atopic dermatitis: an updated systematic review with implications for practice and research. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(3):501–13.

Gambichler T, Othlinghaus N, Tomi NS, et al. Medium-dose ultraviolet (UV) A1 vs. narrowband UVB phototherapy in atopic eczema: a randomized crossover study. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160(3):652–8.

Bulur I, Erdogan HK, Aksu AE, et al. The efficacy and safety of phototherapy in geriatric patients: a retrospective study. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93(1):33–8.

Meduri NB, Vandergriff T, Rasmussen H, et al. Phototherapy in the management of atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2007;23(4):106–12.

Morison WL, Parrish J, Fitzpatrick TB. Oral psoralen photochemotherapy of atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 1978;98(1):25–30.

Wollenberg A, Oranje A, Deleuran M, et al. ETFAD/EADV Eczema task force 2015 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adult and paediatric patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(5):729–47.

Schneider L, Tilles S, Lio P, et al. Atopic dermatitis: a practice parameter update 2012. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(2):295–29927.

Lyakhovitsky A, Barzilai A, Heyman R, et al. Low-dose methotrexate treatment for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24(1):43–9.

El-Khalawany MA, Hassan H, Shaaban D, et al. Methotrexate versus cyclosporine in the treatment of severe atopic dermatitis in children: a multicenter experience from Egypt. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172(3):351–6.

Megna M, Napolitano M, Patruno C, et al. Systemic treatment of adult atopic dermatitis: a review. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7(1):1–23.

Berth-Jones J, Takwale A, Tan E, et al. Azathioprine in severe adult atopic dermatitis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147(2):324–30.

Murphy LA, Atherton DJ. Azathioprine as a treatment for severe atopic eczema in children with a partial thiopurine methyl transferase (TPMT) deficiency. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20(6):531–4.

Meggitt SJ, Gray JC, Reynolds NJ. Azathioprine dosed by thiopurine methyltransferase activity for moderate-to-severe atopic eczema: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367(9513):839–46.

Heller M, Shin HT, Orlow SJ, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil for severe childhood atopic dermatitis: experience in 14 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(1):127–32.

Product Information: DUPIXENT® subcutaneous injection, dupilumab subcutaneous injection. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc (per FDA), Tarrytown; 2020.

Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(24):2335–48.

Gori N, Chiricozzi A, Malvaso D, et al. Successful combination of systemic agents for the treatment of atopic dermatitis resistant to dupilumab therapy. Dermatology. 2021;21:1–7.

Miniotti M, Lazzarin G, Ortoncelli M, et al. Impact on health-related quality of life and symptoms of anxiety and depression after 32 weeks of dupilumab treatment for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35(5): e15407.

Mastorino L, Viola R, Panzone M, et al. Dupilumab induces a rapid decrease of pruritus in adolescents: a pilot real-life study. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(6): e15115.

Reich K, Kabashima K, Peris K, et al. Efficacy and safety of baricitinib combined with topical corticosteroids for treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(12):1333–43.

Simpson EL, Lacour JP, Spelman L, et al. Baricitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis and inadequate response to topical corticosteroids: results from two randomized monotherapy phase III trials. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(2):242–55.

Nezamololama N, Fieldhouse K, Metzger K, et al. Emerging systemic JAK inhibitors in the treatment of atopic dermatitis: a review of abrocitinib, baricitinib, and upadacitinib. Drugs Context. 2020;9:1–7.

Guttman-Yassky E, Thaçi D, Pangan AL, et al. Upadacitinib in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: 16-week results from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(3):877–84.

https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/rinvoq. Accessed 21 Feb 2021.

Simpson EL, Sinclair R, Forman S, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (JADE MONO-1): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10246):255–66.

Del Rosso JQ. Monoclonal antibody therapies for atopic dermatitis: where are we now in the spectrum of disease management? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12(2):39–41.

Lewis-Jones S, Mugglestone MA. Management of atopic eczema in children aged up to 12 years: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2007;335(7632):1263–4.

Green RJ, Pentz A, Jordaan HF. Education and specialist referral of patients with atopic dermatitis. S Afr Med J. 2014;104(10):712.

Reitamo S, Rustin M, Harper J, et al. A 4-year follow-up study of atopic dermatitis therapy with 0.1% tacrolimus ointment in children and adult patients. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(4):942–51.

Sigurgeirsson B, Boznanski A, Todd G, et al. Safety and efficacy of pimecrolimus in atopic dermatitis: a 5-year randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2015;135(4):597–606.

Vestergaard C, Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, et al. European task force on atopic dermatitis position paper: treatment of parental atopic dermatitis during preconception, pregnancy and lactation period. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(9):1644–59.

Thyssen JP, Vestergaard C, Vestergaard C, et al. European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis: position on vaccination of adult patients with atopic dermatitis against COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) being treated with systemic medication and biologics. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(5):e308–11.

Huang X, Xu B. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus versus pimecrolimus for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in children: a network meta-analysis. Dermatology. 2015;231(1):41–9.

Taylor K, Swan DJ, Affleck A, et al. Treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic eczema in adults within the U.K.: results of a national survey of dermatologists. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(6):1617–23.

Harper JI, Ahmed I, Barclay G, et al. Cyclosporin for severe childhood atopic dermatitis: short course versus continuous therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142(1):52–8.

Berth-Jones J, Graham-Brown RA, Marks R, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of cyclosporin in severe adult atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136(1):76–81.

Wollenberg A, Beck LA, Blauvelt A, et al. Laboratory safety of dupilumab in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from three phase III trials (LIBERTY AD SOLO 1, LIBERTY AD SOLO 2, LIBERTY AD CHRONOS). Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(5):1120–35.

Wollenberg A, Blauvelt A, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Tralokinumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from two 52-week, randomized, double-blind, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase III trials (ECZTRA 1 and ECZTRA 2). Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(3):437–49.

Acknowledgements

Funding

The Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia funded this project. Work group received reasonable honoraria for activities related to this publication, and travel and accommodation expenses from the Ministry of Health, KSA. The journal’s Rapid Service Fee was also funded by the Ministry of Health, KSA.

Medical Writing Assistance

Medical writing support was provided by Itkan Health Consulting (Sahar Shami, BSc) and was funded by The Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the concept, writing of the draft content related to their section, reviewed compiled drafts, and approved the final version for publication.

Disclosures

Mohammad I. Fatani received consultancy fees and speaker honorarium from Abbvie, Lilly, Sanofi and Novartis. Mohammed A. Alajlan received consultancy fees and speaker honorarium from Abbvie, Amgen, Jansen, Lilly, Sanofi, and Novartis. Yousef Binamer received research grants, consultancy fees and speaker honorarium from Abbvie, Lilly, Sanofi, Amgen, Novartis and Janssen. Bedor A. Alomari received consultancy fees from Abbvie and Novartis and speaker honorarium from Abbvie, Novartis and Amgen; received research grants from Abbvie and Novartis. Authors Khalidah A. Alenzi, Rayan G. Albarakati, Ruaa S. Alharithy, Ahmed Al-Jedai, Hajer Y. Almudaiheem, Afaf A. Al Sheikh, Maysa T. Eshmawi, and Amr M. Khardaly, declare no conflicts of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fatani, M.I., Al Sheikh, A.A., Alajlan, M.A. et al. National Saudi Consensus Statement on the Management of Atopic Dermatitis (2021). Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 12, 1551–1575 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-022-00762-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-022-00762-6