Abstract

This paper reports the findings of a critical qualitative study on trauma-informed teaching of English as a second language (ESL) at Australian universities. Post-traumatic stress affects verbal learning, yet most ESL teachers do not receive training in trauma-informed teaching. The field has suffered from a dearth of empirical studies and absence of student voice. This study used a validated tool to measure the post-traumatic stress of 39 participants, including international students and former refugees. Twenty of these completed semi-structured interviews about the ESL learning environment, based on a framework of trauma-informed principles. Data were analysed using critical, qualitative methods through a trauma-informed lens. A major theme in the findings was the importance of ESL teachers’ understanding of students. Within this theme, four sub-themes are explored: personal engagement and attention, acceptance and understanding of the learner role, understanding the lives of students outside the classroom and an understanding of students’ cultures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is well established in the scientific literature that trauma and post-traumatic stress can affect learning and engagement. Trauma, defined as any experience ‘that impairs the proper functioning of the person’s stress-response system, making it more reactive or sensitive’, (Supin, 2016, p. 5) leads to an erosion of trust and a loss of control, connection and meaning (Herman, 1997). When responses to trauma become prolonged and intrusive, they are deemed to be disordered (Silove et al., 2007), and a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may be made. Using a qualitative research design, this study examined what traumatised students in university-based English as a second language (ESL) program in Australia perceived as a positive learning environment.

From a learning perspective, trauma and PTSD can impede focus and affect verbal learning, memory and concentration (Brandes et al., 2002; Bustamante et al., 2001; Jelinek et al., 2006; Johnsen & Asbjornsen, 2009; Lindauer et al., 2006; Vasterling et al., 2002). Research has also found that the symptom load of PTSD is inversely correlated with the speed of second language acquisition (Theorell & Sondergaard, 2004). These impacts make educator awareness and understanding of post-traumatic stress pedagogically necessary.

It is highly likely that any ESL program will contain students who have experienced trauma. In a study of almost 70,000 people across 24 countries, 70.4% of respondents reported having experienced psychological trauma (Kessler et al., 2017). While the vast majority of people who experience trauma do not go on to develop post-traumatic stress disorder (Bisson et al., 2015), approximately 4% of adults worldwide will experience PTSD in their lifetime (Koenen et al., 2017). This figure is higher amongst women (Australian Institue of Health & Welfare, 2020, July 23), refugees (Knipscheer et al., 2015), military veterans and emergency services personnel (Wallace, 2020), all of whom could be present in an ESL class. Further, ‘epidemiological data suggest that the majority of college students have been or will be exposed to traumatic events’ (Hoover et al., 2016, p. 151).

Despite this, ESL teachers are rarely sufficiently trained in trauma-informed pedagogy (Finn, 2010; Kostouros et al., 2022). Therefore, educators may be unaware that educational practices and policies can exacerbate PTS responses, undermining learning (Horsman, 1998; Isserlis, 2009; Nelson & Appleby, 2015). While teachers are not therapists, ‘it is in our interests to adopt curriculum, teaching and assessment approaches—informed by psychological principles and research—that may mitigate psychological stressors in the educational environment’ (Baik et al., 2017, pp. 10–11). An understanding of this environment, especially from the point of view of English language learners (ELLs), is, therefore, imperative. Consequently, this study aimed to answer the following research questions:

-

1.

According to adult ESL students experiencing post-traumatic stress, what constitutes a positive ESL learning environment?

-

2.

How do adult ESL students who are experiencing varying levels of post-traumatic stress perceive the effects of the learning environment on their learning and engagement?

Contextualising literature

Trauma-informed second language teaching and adult education

There is a dearth of previous literature that have answered these research questions. Few empirical studies have examined how best to teach traumatised ESL students, and there are significant gaps in the extant research. Only four previous studies privileged student voice (Bajwa et al., 2020; Elliott et al., 2011; Louzao, 2018; McPherson, 1997) and only one of these (McPherson, 1997) focused on adult second language learners. These studies were also hampered methodologically by the absence of a validated trauma screening measurement. In addition, the majority of studies focused on refugee-background students, making international students a neglected cohort. This runs the risk of essentialising refugees as traumatised, perpetuating the narrative of the ‘tragic refugee’ (Espiritu et al., 2022) and also ignores the trauma that exists amongst international students and immigrants, potentially leaving them and their teachers unsupported.

To date, empirical studies of trauma-informed second language teaching have focused primarily on interactions and relationships between teachers and students, the physical set-up of learning spaces and the need to avoid potentially triggering teaching materials. With regards to teacher-student interactions, there are several areas of consensus. A number of studies found the need for teachers to build trust, bonds and rapport with students (Bajwa et al., 2020; Ilyas, 2019; Louzao, 2018; Wilbur, 2016). Other common findings were the benefits of teachers showing concern for the emotional wellbeing of students and listening to and engaging with students individually (Bajwa et al., 2020; Louzao, 2018; Tweedie et al., 2017; Wilbur, 2016). Studies have also shown that providing practical assistance to students for non-academic matters (Ilyas, 2019; Tweedie et al., 2017), teaching inclusively (Bajwa et al., 2020; Ilyas, 2019; Wilbur, 2016) and making students feel valued (Bajwa et al., 2020; Ilyas, 2019; Louzao, 2018; Wilbur, 2016) were also beneficial. However, little detail was provided as to how such practices were enacted.

The effects of such practices from a student perspective were also scantly reported in the previous literature. Student participants in the study by McPherson (1997) reported that easier classes produced enjoyment and learning, and a bilingual class led to one student stating that they felt ‘relaxed and comfortable’ (McPherson, 1997, p. 36). Another study reported that supportive, caring and respectful staff increased students’ confidence, motivation, trust and the ability to connect with others (Bajwa et al., 2020). However, that paper did not specify how students conceptualised behaviour that was supportive and caring.

A study in the high school sector by Louzao (2018) provided additional detail about the ways that second language students perceived the effects of specific teaching acts. That study found that using the same first language of some of his students built trust, which made them more motivated to learn. Engaging personally and positively with students and showing concern for their wellbeing made students feel valued and increased their confidence and desire to excel.

While the findings above are valuable, more research was required in order to uncover more details about teaching approaches that traumatised second language students found positive, and how they perceived the effects of such approaches.

Other informing literature

A broader survey of literature relevant to this study—including conceptual and review papers on trauma-informed Teaching of English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL), socio-environmental theories of trauma and critical/decolonising pedagogies—uncovered factors that relate both to effective learning and recovery from PTSD: a safe and secure environment (Burstow, 2003; Perry, 2006; Silove, 2013), agency and choice (Herman, 1997), foregrounding of student identities (Finn, 2010; Smyth, 2011), recognition of student strengths (Adkins et al., 1998; Burstow, 2003; Ryan & Viete, 2009), social belonging (Schreiner, 2017; Silove, 2013; van der Kolk, 2014) and meaning (Cooke, 2006; Nelson & Appleby, 2015; Pashang et al., 2018; Silove, 2013). Further research was required to ascertain how these principles manifest for ELLs in the learning environment and how they perceived the effects.

Theoretical framework

Two major theoretical perspectives inform the present study: socio-environmental models of trauma and mental health and critical/decolonising pedagogies. Both are often applied in research with marginalised populations, as these perspectives shift the pathology and burden for change from the individual to the social environment. Unlike traditional and neoliberal discourses of mental distress which centre on individual defects (Brown & Baker, 2012; Burstow, 2003; Herman, 1997; Hoover et al., 2016; Maercker & Horn, 2013), socio-environmental models of trauma interrogate social conditions, power and human relationships (Herman, 1997; Maercker & Horn, 2013; Perry, 2006; Silove, 2013; van der Kolk, 2014). Similarly, critical approaches to education reject the deficit view of the student, examining and critiquing social and educational environments (Freire, 1996; Giroux, 1997; Kincheloe et al., 2014; Smyth, 2011; Zinn & Rodgers, 2012).

Aligning with these theoretical perspectives, the study employed a critical qualitative research approach, listening to and foregrounding the voices of those affected (Smith, 2012; Smyth et al., 2014). This approach also aligns with principles of critical pedagogies, which reject the teacher as sole expert, amplify the voices of students and engage teachers and students in a dialogic relationship (Freire, 1996). Despite the dearth of student voice in trauma-informed TESOL, students in general ‘are very perceptive about what helps or hinders their learning’ (Smyth, 2011, p. 99) and offer a rich source of data. Similarly, qualitative mental health research rejects the traditional role of researcher as sole expert (Davidson et al., 2009), valuing ‘experiential as well as academic knowledge’ (Gillard et al., 2010, p. 574). Accordingly, this study privileges student voice to avoid paternalistic assumptions of what is best for ELLs.

Researcher positionality

The lead author (Wilson, hereafter referred to as the researcher) is an Anglophone, Anglo-Celtic Australian who has taught English as an additional language to a diverse range of students from more than 30 countries over 19 years. She is a lecturer in ESL at a regional Australian university with a large proportion of refugee-background students as well as international students from volatile regions such as Iraq. She is also an experienced second language learner and former English as a Foreign Language teacher. As a resident of Fukushima prefecture, Japan in 2011, she experienced major trauma from the magnitude 9 earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster, and subsequently taught English to a community under continuous traumatic stress (Heng, 2017). Consequently, she was diagnosed with PTSD and experienced the impact this has on learning. During this study she was further traumatised by experiencing stage 3 cancer. These lived experiences influenced her positionality and positively impacted the study. Her intercultural competence and TESOL skills, together with insider perspectives of second language learning, ethno-linguistic outsider status and psychological trauma, enhanced communication and understanding with participants and assisted with data analysis.

The other authors, who provided oversight and supervision, brought inclusive teaching and trauma lenses to the research. All are Anglophone Australians. The second author (Le Brocque) has been researching mental health for over 40 years, with a particular interest in PTSD in children and their families. She has published and provided clinical input on the impact of trauma in education contexts. The third author (Drayton) is a teaching-focused academic whose research has centred on bereavement and mental health in social work. The fourth author (Hammer) is a critical researcher who has researched and practised in the discipline of higher education for over 20 years. Her research has focused on learning and teaching in the university context.

Methods

Context and ethics

Participants were recruited from three universities in south-east Queensland, Australia. Two universities were in the state capital and the third in a regional city. Eligible students were 18 years or older, with a minimum English proficiency of lower intermediate. This level of learner was chosen as they were able to converse on a range of topics in English, despite errors in grammar and to meet ethical requirements of the universities involved. The lead researcher has had extensive experience teaching English to students with this level of English language proficiency and was able to adjust her English language level to ensure mutual comprehension with participants. As found by Kosny et al. (2014), using English rather than using interpreters led to interviews being ‘less rushed’ and richer because both parties often rephrased questions and answers to ensure that meaning was understood, leading to ‘more enlightening discoveries’ (Kosny et al., 2014, p. 842).

The participants were all current or past students at a university-based ESL program; most were undertaking their English language course at the time of data collection, and five had completed their course within the previous 12 months. Ethics clearance was granted from the University of Queensland Human Ethics Committee (Approval Number 2018002372) and gatekeeper permission obtained from participating universities.

Research design

The study was designed to fill the gaps identified in the literature review by privileging student voice, including a mix of international, immigrant and refugee ELLs, screening participants for PTSD using a validated instrument; and recruiting participants from university ESL and English for Academic Purposes courses.

The research had two stages: in Stage 1, the researcher administered the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), a validated screening instrument (Weathers et al., 2013). This was chosen for its cross-cultural validity (Ibrahim et al., 2018; Lima et al., 2016), ability to be administered by a non-clinician and accessibility of its English language. A level appropriate glossary was provided for a small number of words. PCL-5 was also selected for ethical reasons, as participants are not required to disclose the source of their trauma which could trigger PTSD responses. Participants rated on a Likert scale of 0–4 ‘how bothered’ they were by the 20 items in the previous month and responses for all items were summed to create a total score (National Center for PTSD, 2013, p. 2). Possible scores on the PCL-5 range from 0 to 80, with scores of 31 and above considered to be in the clinical range of PTSD (National Center for PTSD, 2013). The PCL-5 was used as a screening tool and not intended as a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder. Responses are likely to be under-reported due to stigma, avoidance and numbing (D’Andrea et al., 2012; Patel et al., 2017).

A comparison of the emerging themes between participants with low, medium and clinical level symptoms was undertaken; however, negligible differences were found in terms of their views on the learning environment. By obtaining and including qualitative data from participants with varying levels of post-traumatic stress, the study elucidates which aspects of the current second language teaching environment are best practice for a range of students, regardless of trauma history.

Stage 2 of the research was a semi-structured, individual interview between the researcher and selected participants. The interview consisted of 16 open-ended questions about the experience of learning English at their university in Australia, with 13 of these questions directly aligned to trauma-informed principles identified in the broader literature review; that is, safety and security, agency and choice, the foregrounding of identities; recognition of strengths, social belonging and meaning (See Appendix). Inclusion in Stage 2 was largely a convenience sample, but efforts were made to ensure a range of PCL-scores, gender balance and a mix of ethnicities and student status. The latter was considered pertinent because international and domestic students often have different supports and stressors outside the classroom.

Interviews were conducted from June 2019 to January 2021. Pre-COVID, the researcher conducted in-person questionnaires and interviews. From March 2020, the researcher administered PCL-5 online and held interviews via Zoom videoconferencing. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by the researcher. To preserve the voices of the participants, non-standard grammar and vocabulary were not corrected, but fillers, hesitation devices and false starts were removed where they impeded flow. Participants were emailed a copy of their interview transcript and given the opportunity to add or alter material, and the researcher asked additional follow-up questions via email so that students could confirm the researcher’s interpretation of concepts where necessary.

Participants

Thirty-nine students completed Stage 1 of the research, and of these, 20 completed Stage 2. Demographic information and PCL-5 scores of participants who took part in both stages of the research are provided in Table 1. Ethnicity is included if participants considered this pertinent to their identity. For this reason, citizens of Hong Kong and Taiwan are identified as such rather than described as Chinese.

Data analysis

To maintain consistency with the broader epistemologies and theoretical framework of the project, data were analysed with a critical thematic approach (Lawless & Chen, 2018) through a trauma-informed lens. This allowed a privileging of the voices of participants and an analysis of power, as well as a sensitivity to principles of trauma-informed practice.

Lawless and Chen (2018) proposed a two-step process consisting of open and closed coding. In Step 1, the lead researcher undertook a close reading of the interview data to identify patterns that were ‘important, salient, or meaningful’ to participants as a group or individually (Lawless & Chen, 2018, p. 98). In this step, the priority was ‘understanding, privileging, and honoring what our participants were actually saying and revealing to us about their social worlds and how these phenomenological experiences were similar across experiences’ (Lawless & Chen, 2018, p. 98). Themes were ascribed based on their ‘repetition, recurrence, and forcefulness’ (Lawless & Chen, 2018, p. 98) and were reviewed by each member of the research team.

In Step 2, the researchers considered ideologies and power relationships that were revealed in these themes (Lawless & Chen, 2018). This approach challenged ‘dominant structures and create[d] spaces, pathways, or opportunities for social justice’ (Lawless & Chen, 2018, p. 12). In this stage, the researcher analysed data as above and through a trauma-informed lens. The latter involved interpreting data in terms of how they related to trauma-informed principles. All data analysis was reviewed by members of the research team.

Findings

The findings reported here are part of a larger study (Wilson, 2022, 2023). This paper presents findings related to the first theme: attunement and responsiveness by teachers. Within this overarching theme, the researchers identified four sub-themes: personal engagement and attention; acceptance and understanding of the ELL role; understanding of the lives of students outside the classroom and understanding and responsiveness to culture.

Personal engagement and attention

Interview participants considered staff-student relationships and interactions to be of paramount importance to the learning environment; more than just ‘caring’, participants characterised effective teachers and other staff as having ‘connection’ and ‘involvement’ with students, treating them as individuals rather than ‘just dealing with us as students’ [S36].

They interact with you in a good way. They feel you have something to say. [S1]

Such interactions led to greater understanding and confidence, according to participants.

It started with being kind, respect, and the teaching style. I was really feeling comfortable to continue with my studies. [S40]

Participants also reported that when they felt that they had a ‘connection’ with teachers—rather than simply a transactional relationship—the learning environment was more positive.

I think the interaction between the students and the teacher makes it feel like a good environment. When you go to study and you learn and you feel like you are satisfied with what the teacher is providing and the connection and the help that you get from the teachers, it makes it quite a good environment. [S37]

This connection, according to some participants, made them feel more confident about expressing themselves in class. One interviewee contrasted teachers who ‘just finish [their] work and go out of the class’ with those who have some ‘involvement with the students’ [S38]. He stated that the former made him feel ‘confused’ and reluctant to ask questions, as ‘I don’t even know what’s the right question to ask’ [S38]. However, with teachers who paid more personal attention to students,

It was so easy for me to ask questions, even if it’s not right […] I will feel confident because the relationship—it just gives you confidence to ask whatever you want, even if it’s wrong. [S38]

Other participants described feeling ‘safe’, ‘comfortable’ and ‘relaxed’ when interacting with teachers who engaged personally, and they reported the effect this had on motivation.

I tell myself I need to do better ‘cause they care (about) me so much, and then I shouldn’t let them down. [S8]

Apart from general descriptions of teachers being ‘involved’, ‘connected’ with and interested in students, participants reported personal engagement and attentiveness of teachers in specific ways. They discussed effective teachers answering questions fully, patiently and with an understanding of students that demonstrated careful listening. This was in turn made possible by minimising ‘teacher talk time’, or the percentage of the class that the teachers was speaking. Participants also gauged the involvement of teachers by the level of attention they paid to individual student work and progress and by the empathetic delivery of feedback.

Listening and answering questions

Participants stressed the importance of teachers and managers paying attention to students, listening and responding with understanding. These staff members were described by participants as showing care and respect, ultimately leading to learning.

If there is no communication and understanding or listening to one another, then there’s no learning. [S40]

Listening also meant that teachers answered individual questions with patience, in detail and in a timely manner. One participant summarised the opinions of other interviewees when he said he felt ‘respected’ by teachers because ‘they just answer my questions carefully’ [S8]. When asked if respect was important for second language learning, he responded:

Um…[laughs] Imagine if others don’t respect you, will you have some negative emotion? Yeah, maybe you will have some negative emotion and that just may be an obstacle for you to learn English because you don’t get courage, so there is no motivation for you to study. [S8]

Close attention to students also allowed teachers to anticipate questions, according to participants.

My teacher always look at people’s face and sometimes, I didn’t tell anything, but she see my face and think that I want to speak. [S4]

Similarly, participants discussed teachers who were so attentive and attuned to students and their learning perspectives that they were able to ‘interpret’ learner English.

[If] they feel like we can’t explain something, they give us the words and ask, ‘Is that what you mean?’ Something like that. So it’s very easy for us to explain something when we don’t have the words to explain about something. [S23]

They interpret what the student said and make sure [they] interpreted correct. [They] pay attention and try to understand the student, in order to guide [them] to the right information or right question from their experience as a teacher. [S38]

In contrast, participants reported that teachers who were more transactional in their teaching style did not engage in reflective listening, tended to misunderstand student questions and did not try to negotiate meaning. Participants said this resulted in them feeling frustrated, deterred them from speaking up in class and compelled them to seek assistance elsewhere.

I was not asking a lot of questions, ’cause I was feeling like, he won’t understand me […] I feel like I just better stop and maybe do it with the students or my phone. [S38]

Thus, participants reported that the listening skills of teachers facilitated interactions which, in turn, allowed students to engage more fully with material in the class environment.

Teacher talk time

Listening and responding to student needs also required teachers to minimise their ‘teacher talk time’ according to participants. They described teachers with high levels of talk time as trying to force attention on themselves rather than focusing on students and their English language production. Participants expressed frustration at teacher-centred classes, as these meant that they had fewer opportunities to interact in English and practise the target language.

Interviewees also reported that teachers with high levels of teacher talk time appeared to lack awareness of the impact this had on students. They described teachers who were overly focused on talking about themselves or telling irrelevant stories, which they said caused boredom and confusion in the class. Participants reported that they felt ignored and resentful in classes with high ‘teacher talk time’, causing students to disengage, especially when classes were online via videoconference.

If [teachers] are going to be speaking for the whole entire time, I am more than happy to just turn the screen off, keep my headset [mute]. [S39, emphasis in original]

This participant reported that the teacher mandated that all students had their cameras on and speakers unmuted (classes were held online due to COVID-19 restrictions). However, according to this participant, this was less about promoting engagement and more about surveillance and ensuring that ‘everyone was there watching her and listening to her’ [S39].

Attention to student work and progress

Attentiveness and personal engagement with students also took the form of teachers paying careful attention to individual student work and progress, according to participants. One described feeling that her teachers ‘watched over [students] carefully or affectionately’ [S11]. Similarly, other participants reported that teachers who paid attention to their progress gave them ‘courage’, [S8] and engendered self-belief, trust in the university and increased motivation.

Participants also valued teachers who identified learner errors and provided constructive feedback. Some participants commented that they did not receive specific feedback on their work and this impeded learning; in contrast, those who did receive correction explicitly characterised it as a demonstration of teacher care.

They always send me a feedback. So that’s really helpful for me to improve my English skill and to notice the error I didn’t notice by myself. That’s why they’re really kind and care about me. [S35]

Attentiveness to progress was also connected to attention to the emotional wellbeing of students, with participants reporting that teachers who provided feedback in an empathetic and non-blaming manner added to their confidence.

They use a very gentle way to tell you [that] you need to correct your mistakes. [S8]

The tone with which teachers delivered feedback was considered extremely important to participants and allowed them to make mistakes without being shamed.

Acceptance and understanding of the ELL role

In addition to personal engagement and attention, another facet of being attuned to and responding to the needs of ESL students that emerged in the data was teachers’ acceptance and understanding of the ELL role. Participants discussed the importance of teachers understanding students as bi- and multilingual ELLs rather than viewing them through a monolingual lens.

Here when you speak is not correct, or pronunciation is not very good, no one will blame you because you are not a native speaker […] They won’t blame you because they think it’s normal. [S5]

They will tell us language learning is step by step […] They will say ‘Oh, I can’t speak any word of Chinese’. [S7]

Participants also praised teachers who were able to understand and be understood by ELLs. In a context where students are still developing their English and where teachers rarely share the same first language as their linguistically diverse cohort, understanding is potentially fraught. Many participants discussed their apprehension and anxiety about speaking English in case this led to humiliation.

When I talk with strangers I feel like scary to make mistakes, make misunderstand with the strangers. So I feel stressed when talk to strangers. [S6]

At first I’m afraid of what people might think of me. And I dare not speaking because I afraid they would find out I speak terrible English. [S8]

It can be stressful to speak a different language and speak out. [S11]

Participants stated that these fears were mitigated by teachers who understood learner English and reacted with patience to irregularities in their English language production.

Teacher is very kind so I feel very safe and comfortable […] When I speak in English with strangers, I feel very nervous and feel hesitation but my classmates are very kind and teacher also very kind so I feel relaxed and can speak very fluently. [S6]

Participants often used the word ‘accept’ to describe the way that teachers responded to ELLs and learner English. This sense of acceptance and non-judgement was further emphasised by interviewees’ use of the phrase ‘they do not mind talking to us’ and similar terminology.

They don’t mind talking with those people they can’t speak fluent English or English language ability not really good. They have a lot of patience. […] they don’t mind talking with you and they accept you. [S7]

They will be more patient and try to explain more and they will not mind to take longer time than talking or speaking to the native speaker. [S22]

Even though our English skill is poor, they kindly teach us. […] in my case, in the speaking, I pause sometimes in the middle of statement, but they can accept and listen to it all. [S35]

Other ways that teachers accommodated ELLs, according to participants, was by grading their language, speaking more slowly and making genuine efforts to understand learner English. Such practices provided students with a sense of confidence in their own English abilities.

I can understand what teachers are talking about so that made me have more confidence. […] Like ‘Oh I can understand! So my English not bad’. […] So that make me feel more confident and willing to learn English. [S5]

Sometimes [teachers] might not fully understand what the student saying but trying to do so is really important in my view [because] I think it gives the student the courage to be open and build a good confidence and therefore, this will take off the fear of saying something in your second or third language. [S38]

Thus, participants reported that demonstration of understanding and empathy for learning an additional language made teachers responsive to the needs of students, which in turn gave students the confidence and willingness to persist.

Understanding students’ lives outside the classroom

The third aspect of understanding that emerged in the interview data was teachers understanding and responding to the lives of students beyond the classroom. Many participants reported that, rather than restricting their role to teaching English, some teachers showed an understanding of the transition challenges facing students. This contributed to a positive learning environment, in their view.

I think both teachers that I had in the past, they were always giving us advice on places where we can go and enjoy, have some fun, some place where we can go and buy stuff—cheaper stuff—where we can go and eat. [S21]

Every 2 weeks my teacher, after the class leave, she sit with me and ask me about my experience, how I feel, what I usually do on the weekends and she try to give me advice to do things, like activities in [city]. And actually, I shocked and I was happy with it. I didn’t know that the teacher would feel that I was struggling in the first weeks. And she did a great job with me. [S1]

Participants also equated teacher care with attention to the health and wellbeing needs of students.

Sometimes you come stressed, sometimes you are not feeling OK. For example, you might have a headache and you still trying to go and then when they notice. For example, [a teacher] did that to one of students. She was having a headache and she was trying to be there. [The teacher] asked her if she was OK, if she need to go home and she was like, ‘Oh, yeah, I appreciate that’. [S40]

They were also always giving us tips on wellbeing, for example, when the Corona [virus] situation started to raise, so they took some of their time to treat our personal issues that are not strictly related to our studies. So I think in that way they care about us. [S21]

With the onset of COVID-19 in 2020, participants perceived that individual teachers extended their attentiveness and subsequent support further.

They always notice the difficulties of the students and they are always there to help us. Once there were no rice at the supermarket, our teacher promised me to bring me some rice […] I have no words to say thanks to her. [S23]

Teachers who were sensitive to the non-verbal cues of students were particularly valued by participants, who reported some teachers noticing and responding to these.

They study to notice if there is something that a student feels uncomfortable with. They notice it before that. [S40].

When they saw the student like long face they will ask ‘How was your day and why you is …?’ Like one time, my classmate she got her period so maybe her face looked white, so when teacher noticed she might be not comfortable and she show her care. [S5]

Similarly, teachers who showed an understanding of and flexibility for, the outside demands of students added to a human learning environment. Participants reported some teachers being understanding of the impact of part-time jobs and children on the classroom attendance of students.

Some students are already mother or father and yeah, they have they have a kids. Then if their kids come to the [Zoom] classes, but teachers can accept the situation. [S35]

In sum, the ability of teachers to understand ELLs as people with lives beyond the classroom, to ‘read’ them and respond in an empathetically and with concrete support, all contributed to participant perception of a positive learning environment.

Understanding of cultures

The final aspect of understanding and responsiveness that emerged in the data was an attentiveness to the cultures of students. Participants privileged their collective identities over their individualised identities. Despite the generally high levels of education and/or workplace skills of participants, they considered their individual backgrounds irrelevant in the context of English language learning. Instead, they commented on the impact of teachers understanding and respecting their culture, ethnicity and religion.

When they respect our culture, we don’t feel any stress. We can do our learning in a free environment where we are free to speak and free to do things, free to learn well. [S23]

I feel like being acknowledged, being respected and it’s make me feel like I am being valued too. [S40]

It make me relieved to speak what I believe and so no one will judge me about it. And that’s good. [S1]

In contrast, lack of understanding of cultural differences led to conflict and dissatisfaction, with some participants reporting cultural disrespect. They also stressed the importance of teachers taking the time to understand the different cultural perspectives driving their students.

Some people, they already did their own research about other people, […] [they have] been to different places and have a clue what it means, a clue how other people do the things [S40]

According to participants, cultural responsiveness includes an understanding of the culture shock students may be experiencing.

We are not from this country so—and for me for example, I just came alone and I am trying to find my way here by my own, and I find in my teachers a place where I can put all of my doubts, let’s say. If I don’t know something, I can just ask them if they are open enough. [S21]

Cultural differences in communication also posed difficulties for some participants, and they reported that whether or not teachers understood could raise their stress levels.

At first I was kind of overwhelmed because in Japan we don’t have to say much, right? I think you know this, that we do not express everything. Silence or not saying anything means something […] I think if you are shy, it is stressful to speak out. [S11]

In addition, participants emphasised the importance of teachers and other university staff understanding and respecting the national or ethnic identities of students, especially when such identities are contested. Participants from Taiwan and Hong Kong discussed conflict with Chinese classmates over the legitimacy of self-government, but in each case reported that teachers intervened to pacify the situation.

Discussion and implications

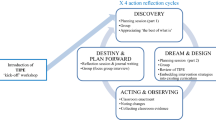

This paper has presented the perspectives of traumatised adult ESL students regarding a positive learning environment, and how they perceived the effects of the learning environment. A major theme identified from the findings was the importance of ESL teachers being attuned to their students, that is, having the ability to understand and respond to student needs. Findings related to this theme are represented in Fig. 1. According to participants, teachers who were closely attentive and empathic to students—paying attention to non-verbals and interpreting their learner English—were better able to understand them. This understanding in turn led to teachers having the ability to respond to and anticipate the academic, personal and cultural needs of students. Consequently, students reported feelings of safety, belonging, acceptance, connection, motivation, self-belief and confidence, which they said led to agency and ultimately, learning. Conversely, teachers who engaged in high ‘teacher talk time’ caused students to report feeling less engaged and more disempowered.

Interpretation and contextualisation of findings

The findings of this study support and extend the findings of earlier research in trauma-informed second language education and in humanising pedagogies more generally. They also provide empirical support for theoretical and conceptual articles in this space. Moreover, they provide an important counterpoint to much of the literature in associated fields, such as second and foreign language anxiety, in which the teacher and learning environment are often decentred or learner affect is treated as a psychological variable or learner trait (Dewaele, 2017; Dikmen, 2021; Khasinah, 2014; Thurman, 2018). Studies that present learner anxiety as dependent on the teaching and learning environment represent a minority position (Cameron, 2022; Cao, 2011; Norton, 2013). In the majority of second and foreign language anxiety literature, learner anxiety is presented as an individual deficit (Dewaele, 2013, 2017; King & Smith, 2017; Oxford, 2017; Şimşek & Dörnyei, 2017). In such studies, the learning environment is rarely analysed, apart from offering brief general advice to create a supportive classroom environment (Dewaele, 2013; King & Smith, 2017; Thurman, 2018).

More often, strategies for managing learner anxiety are divorced from TESOL pedagogy. Recommendations for teachers involve encouraging students to be responsible for their emotions by using relaxation techniques (Oxford, 2017; Woodrow, 2006); cognitive behavioural tools (King & Smith, 2017; Oxford, 2017); exposure therapy (Oxford, 2017); social skills training (Oxford, 2017); various positive psychology techniques such as ‘letting go of grudges’ (Oxford, 2017), ‘a good attitude’, optimistic thinking (Oxford, 2016), writing gratitude letters, altruism, positive visualisation and self-talk (Oxford, 2017; Thurman, 2018); and reinterpreting ‘a physiological cue (i.e. increased heart rate before meeting a native speaker) to a positive, enthusiastic emotion’ (Thurman, 2018, p. 4). ESL teachers are also advised by such researchers to ‘teach learners to combat boredom, avoid hyper-intention and hyper-reflection’ (Oxford, 2016, p. 21). These strategies firmly place anxiety and affect within the personal responsibility of language learners rather than seeing them as a product of the teaching and learning environment.

In contrast, the current study demonstrates that the teaching environment can and does affect students’ levels of stress while learning, despite experiences of trauma and the presence of post-traumatic stress responses. The following section provides further contextualisation and interpretation of the findings of the present study.

Personally engaged teachers

Supportive, caring and respectful teachers have been found previously to be important factors in a trauma-informed second language learning environment (Bajwa et al., 2020; Elliott et al., 2011; Ilyas, 2019; Louzao, 2018; Wilbur, 2016). Similar findings have also been made with respect to international students at Western universities (Glass et al., 2015; Heng, 2017; Ryan & Viete, 2009) and degree-level students at Australian universities (Baik et al., 2019). However, few details have been provided about how students—particularly ESL students who have experienced trauma—perceived these attributes in teachers. The present study has provided greater insight into how students may conceptualise caring and respectful relationships and behaviour.

The present study has also confirmed and extended the findings of Louzao (2018) in relation to ESL students and the findings of Baik et al. (2019) in relation to students at Australian universities. In the former study, student participants reported that individual engagement with their teacher improved their learning experience (Louzao, 2018). The latter study included students expressing a wish for their teachers to know their names and to be ‘more interactive with students’ (Baik et al., 2019, p. 680). The present study has explained in participants’ words how teachers’ attention to students led to attunement and, thus, the ability of teachers to better meet student needs.

Participants said that teachers who were fully present emotionally and mentally gave them the confidence to ask questions, as they knew that these teachers had both the will and the ability to understand. Teachers who were able to understand students when they didn’t ‘have the words to explain about something’ [S23] supports the observation by Norton (2013) that ‘if the target language speaker is as invested in the conversation as the language learner is, she or he may work harder to achieve such understanding’ (p. 107). The ability of engaged teachers to understand ESL students and ‘guide [them] to the right information or the right question’ [S38] may also be considered a form of attunement.

Although attunement has been examined in other areas of education (Lutzker, 2014; Marucci et al., 2018) and psychotherapy (Erskine, 1993, 2020), it is an underexplored area in TESOL. ‘More than just understanding, attunement is a kinesthetic and emotional sensing of the other—knowing the other’s experience by metaphorically being in his or her skin’ (Erskine, 1993, p. 187). Attunement enables a traumatised person to feel safe enough to express needs and feelings, knowing that the response will be empathetic (Erskine, 1993). Although the ESL classroom is not a therapeutic environment, this definition aligns closely with the experiences described by the students in the present study, where empathy, noticing and a trusting relationship led to accurate interpretation of the non-verbal cues and partially articulated utterances of ELLs. More research is needed to examine the concept of attunement in mainstream TESOL, trauma-informed teaching and higher education andragogy.

Understanding students as English language learners

Teachers’ understanding of students’ (temporary) identities as English language learners (ELLs) is an original finding in the field of trauma-informed second language teaching research. The practice of understanding and meeting students at their level of development—rather than blaming and shaming them for errors—was not reported by previous empirical studies. Although the student participants of McPherson (1997) called their classes ‘high pressure’, ‘too difficult’ (p. 34) and stated a need for scaffolded learning and slower paced classes, the findings were not explored further in that study. A similar finding was made by Norton (2013) in her longitudinal case study of adult ELLs in Canada. She noted that one of the participants of that study ‘not only wanted to be accepted, she wanted her “difference” to be respected’ in terms of English language proficiency and cultural competence (Norton, 2013, p. 111).

Participants in the present study contrasted ESL teachers who ‘accepted’ them as language learners with those who ‘blamed’ them for errors. Participants explicitly linked such behaviours to their confidence levels. Shaming students for errors—instead of scaffolding their English and expecting non-native proficiency—acted as a barrier to learning, regardless of post-traumatic stress levels. Blaming and judgement are intricately tied to shame responses, leading to recipients ‘being overwhelmed with an intense feeling of conspicuousness’ (Dolezal & Gibson, 2022, p. 4).

Shame has particular significance for individuals who have experienced trauma. While it is a ‘defining and central feature of human experience and all human relationships’ (Dolezal & Gibson, 2022, p. 3), shame is theorised to hold a key position in understanding post-traumatic stress (for an overview of the literature, see Dolezal & Gibson, 2022). As such, trauma-informed relationships are ‘nonshaming and nonblaming’ (Elliott et al., 2005, p. 466). Therefore, teaching ELLs without judgement is important for all students, but particularly those who have experienced trauma.

Understanding and caring for students’ lives outside the classroom

Participants in this study felt a sense of safety and worth when teachers showed care for their lives beyond the ESL classroom. Previous studies on trauma-informed second language teaching with high school ESL students made similar findings (Louzao, 2018; Tweedie et al., 2017), as did a study of adult beginner ELLs in New Zealand (Ilyas, 2019). Similarly, Baik et al. (2019) found that students wanted their lecturers to understand and accommodate their ‘diverse circumstances and commitments’ (Baik et al., 2019, p. 681).

The present research project confirms that ELLs beyond high school and basic levels of English language learning perceive the pastoral role of the ESL teacher as important. It also aligns with the findings of McLachlan and Justice (2009) that international students were often reluctant to seek help, tending instead ‘to suffer quietly and not seek assistance’ (p. 30). In that study, international students reported that they wanted ‘someone to come to them, and tell them, “Is everything OK? Is anything wrong with you? Do you want to talk about something?”’ (McLachlan & Justice, 2009, p. 30). Similarly, participants in the present study emphasised the positive impact of teachers who noticed unspoken student needs and offered pre-emptive support.

These complementary findings suggest that despite Australian universities compartmentalising ‘wellbeing’ into specialist departments, student welfare requires a holistic, whole-of-institution approach. This has been similarly observed by Baik et al. (2019), who noted ‘social interactions in the teaching and learning environment as an important resource for student wellbeing’ (p. 683). Students from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, who are at higher risk of mental ill-health than Australian-born students, are less likely to seek formal psychological help (Orygen, 2017). Furthermore, a UK study of torture survivors found that their ‘perceived level of affective social support had a greater protective effect than any other factor including mental health treatment’ (Hodges-Wu & Zajicek-Farber, 2016, p. 3). Together, these findings demonstrate that pro-active pastoral care by teaching staff is important for not only trauma-informed TESOL, but for adult students generally.

Understanding and respecting the cultures of students

Previous empirical studies of trauma-informed second language teaching did not refer to cultural responsiveness in their findings. In some studies there was a suggestion by researchers that cultural factors negatively affected learning (Holmkvist et al., 2018; McPherson, 1997). However, no details or empirical support were provided. Various studies discussed culture only in terms of how it affects the way people express and view post-traumatic stress (Bajwa et al., 2020; Gordon, 2015; McPherson, 1997; Wilbur, 2016). Meanwhile, Montero (2018) claimed that cultural competence ‘alone may not be sufficient for fostering positive mental health and wellbeing’ for students (p. 93) but did not test this proposition in her study. Wilbur (2016) included cultural imperialism in the theoretical framework of her study; however, culture appeared in the findings only in terms of instructors not wanting to stereotype their students based on their backgrounds.

Despite the underexplored role of culture in research on trauma-informed teaching, the findings of the current study support research that examines language learning and identity (Norton, 2013). These results are also consistent with culturally responsive pedagogies (Gay, 2000; Morrison et al., 2019), which are ‘those pedagogies that actively value, and mobilise as resources, the cultural repertoires and intelligences that students bring to the learning relationship’ (Morrison et al., 2019, p. v). Culturally responsive pedagogical practice includes teachers being ‘socioculturally conscious’ taking a strengths-based approach to culturally diverse students and knowing about their students’ lives (Morrison et al., 2019, p. 18).

Cultural responsiveness is also deeply tied with a sense of safety and, thus, learning. Hammond (2014) defined culture as ‘the way that every brain makes sense of the world’ (p. 22). Beyond surface elements of food and festivals, ‘deep culture’ refers to the underlying assumptions behind a person’s worldview (Hammond, 2014). Significantly, deep culture ‘governs how we learn new information’ and any ‘[c]hallenges to cultural values at this level produce culture shock or trigger the brain’s fight or flight response’ (Hammond, 2014, p. 23).

Challenges to the cultural orientations and identities of students may be unintentional on the part of teachers, but can be harmful nonetheless. As Norton (2013) argued, second language learners ‘are far more vulnerable to the attitudes of the dominant group than the dominant group is vulnerable to them’ (pp. 155–156). This perspective has added more weight of meaning to participants’ expressions of relief at being accepted and respected in the ESL classroom.

Through a lens of Anglo-Saxon Australian experience, a concept of safety associated with cultural and religious acceptance may be difficult to fully comprehend. One participant in the present study disclosed that in order to survive, she had had to hide her true cultural-religious identity in the countries where she was born and sought initial asylum. When a person’s core identity exposes them to genocidal threat, trauma and confusion around that identity often ensue (Berger, 2004). Discrimination based on ethnic, cultural and religious background can also cause minorities to suppress their identities in contexts that are less existentially threatening yet still traumagenic. This includes acculturating to White (Christian) culture and norms by changing their behaviour, speech and appearance ‘so as not to stand out’ (Liu et al., 2019, p. 149).

Explicit or implicit rejection of core identities is not only traumatic in and of itself; it is felt more acutely by trauma survivors. A traumatised adult learner ‘in a state of alarm’ is more ‘attentive to non-verbal cues such as tone of voice, body posture, and facial expressions’ (Perry, 2006, p. 24). Conversely, ‘the threat of social exclusion increases attention to signs of social acceptance’ (De Wall et al., 2009, p. 738). The participants of the present study demonstrated acute sensitivity to acceptance by their teachers; at times their responses indicated low standards for what they considered caring behaviour, such as teachers answering questions. Therefore, it is imperative for second language teachers to interact with students in a way that shows welcome and acceptance.

None of the participants in this study raised sexual or gender identities. However, it would be reasonable to extrapolate that the same principles would apply to those who belong to persecuted gender and sexual minorities. Other aspects of culturally responsive pedagogies are discussed below in the section on transformative second language learning.

Conclusion

The findings of this study challenge technicist approaches to second language acquisition which cast the ELL as ‘a one dimensional acquisition device’ (Pennycook, 2001) and complements the literature of student mental wellbeing (Baik et al., 2017, 2019) and student belonging (Tinto, 1987, 2015). The findings presented here also build on existing evidence that the teacher-student relationship is central to trauma-informed TESOL and extend this evidence in several important ways. Unlike previous studies, participants were pre-screened for PTSD, allowing for more research validity and a comparison between those with high and low post-traumatic stress. However, no difference was observed in the emerging themes. By privileging student voice and structuring the research within a framework of trauma-informed principles, this study has provided a deeper level of detail and more targeted investigation of how the language learning environment affects ELLs. It also widens the scope of trauma-informed ESL to include international students, who have been largely excluded from previous discussions in this field. This study is significant in that it specifically asked students questions that aligned with trauma-informed principles. The fact that the findings align with other theories and empirical research into humanising pedagogies with non-traditional students bolsters the earlier research. It also provides empirical evidence for the first time—to the best of our knowledge—that a culturally responsive approach is an important aspect of trauma-informed practice in second language teaching.

Limitations

As this study is a qualitative investigation of ELLs at a pre-intermediate level and above at university English centres in Australia, the results cannot be generalised beyond that context. It is possible that traumatised ELLs who do not reach that level of English language proficiency would report different experiences of the learning environment.

Future directions

More research is also needed to inform policy and practice in the TESOL field and for teaching culturally and linguistically diverse students. The model in Fig. 1 provides a new model to understand the mechanisms that help create trauma-informed classrooms and may be used to improve teacher engagement and measure student satisfaction in ESL courses. The study clearly shows that ELLs perceive a positive learning environment as one in which teachers engage with them on a personal level, to the benefit of both their learning and wellbeing. Accordingly, ESL teacher training and evaluations should recognise the importance and benefits of attunement, understanding and responsiveness as fundamental to effective and holistic andragogy.

Data availability

Due to ethics and privacy considerations of participants, the raw interview data are not available.

References

Adkins, M. A., Birman, D., Sample, B., Brod, S., & Silver, M. (1998). Cultural adjustment and mental health: The role of the ESL teacher. Spring Institute for International Studies.

Australian Institue of Health and Welfare. (2020). Stress and trauma. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/stress-and-trauma

Baik, C., Larcombe, W., Brooker, A., Wyn, J., Allen, L., Brett, M., James, R. (2017). Enhancing student mental wellbeing: A handbook for academic educators unistudentwellbeing.edu.au

Baik, C., Larcombe, W., & Brooker, A. (2019). How universities can enhance student mental wellbeing: The student perspective. Higher Education Research & Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1576596

Bajwa, J. K., Kidd, S., Abai, M., Knouzi, I., Couto, S., & McKenzie, K. (2020). Trauma-informed education-support program for refugee survivors. Canadian Journal for the Study of Adult Education, 32(1), 75–96.

Berger, A. L. (2004). Hidden children: The literature of hiding. In A. L. Berger & G. L. Cronin (Eds.), Jewish American and Holocaust literature: Representation in the postmodern world. State University of New York Press.

Bisson, J. I., Cosgrove, S., Lewis, C., & Roberts, N. P. (2015). Post-traumatic stress disorder. The British Medical Journal. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h6161

Brandes, D., Ben-Schachar, G., Gilboa, A., Bonne, O., Freedman, S., & Shalev, A. (2002). PTSD symptoms and cognitive performance in recent trauma survivors. Psychiatry Research, 110(3), 231–238.

Brown, B. J., & Baker, S. (2012). Responsible citizens: Individuals, health, and policy under neoliberalism. Anthem Press.

Burstow, B. (2003). Toward a radical understanding of trauma and trauma work. Violence against Women, 9(11), 1293–1317.

Bustamante, V., Mellman, T. A., David, D., & Fins, A. I. (2001). Cognitive functioning and the early development of PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 14(4), 791–797.

Cameron, D. (2022). Willingness to communicate in English as a second language as a stable trait or context-influenced variable. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.1075/aral.36.2.04cam

Cao, Y. (2011). Investigating situational willingness to communicate within second language classrooms from an ecological perspective. System, 39(4), 468–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2011.10.016

Cooke, M. (2006). “When I wake up I dream of electricity”: The lives, aspirations and ‘needs’ of adult ESOL learners. Linguistics and Education, 17(1), 56–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2006.08.010

D’Andrea, W., Chiu, P. H., Casas, B. R., & Deldin, P. (2012). Linguistic predictors of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms following 11 September 2001. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 26(2), 316–323. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1830

Davidson, L., Ridgway, P., Schmutte, T., & O’Connell, M. (2009). Handbook of service user involvement in mental health research [ProQuest Ebook Central version]. Hoboken: Wiley.

De Wall, C. N., Maner, J. K., & Rouby, D. A. (2009). Social exclusion and early-stage interpersonal perception: Selective attention to signs of acceptance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(4), 729–741. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014634

Dewaele, J. M. (2013). The link between foreign language classroom anxiety and psychoticism, extraversion, and neuroticism among adult bi- and multilinguals. The Modern Language Journal, 97(3), 670–684. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2013.12036.x

Dewaele, J. M. (2017). Are perfectionists more anxious foreign language learners and users. In C. Gkonou, M. Daubney, & J. M. Dewaele (Eds.), New insights into language anxiety (pp. 70–90). Multilingual Matters.

Dikmen, M. (2021). EFL learners’ foreign language learning anxiety and language performance: A meta-analysis study. International Journal of Contemporary Educational Research. https://doi.org/10.33200/ijcer.908048

Dolezal, L., & Gibson, M. (2022). Beyond a trauma-informed approach and towards shame-sensitive practice. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01227-z

Elliott, D. E., Bjelajac, P., Fallot, R. D., Markoff, L. S., & Reed, B. G. (2005). Trauma-informed or trauma-denied: Principles and implementation of trauma-informed services for women. Journal of Community Psychology, 33(4), 461–477. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20063

Elliott, M., Gonzalez, C., & Larsen, B. (2011). U.S. Military veterans transition to college: Combat, PTSD, and alienation on campus. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 48(3), 279–296. https://doi.org/10.2202/1949-6605.6293

Erskine, R. G. (1993). Inquiry, attunement, and involvement in the psychotherapy of dissociation. Transactional Analysis Journal, 23(4), 184–190.

Erskine, R. G. (2020). Relational withdrawl, attunement to silence: Psychotherapy of the schizoid process. International Journal of Integrative Psychotherapy, 11, 14–28.

Espiritu, Y. L., Duong, L., Vang, M., Bascara, V., Um, K., Sharif, L., & Hatton, N. (2022). Departures: An introduction to critical refugee studies. University of California Press.

Finn, H. B. (2010). Overcoming barriers: Adult refugee trauma survivors in a learning community. TESOL Quarterly, 44(3), 586–596.

Freire, P. (1996). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Penguin Books.

Gay, G. (2000). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. Teachers College Press.

Gillard, S., Turner, K., Lovell, K., Norton, K., Clarke, T., Addicott, R., Gerry, M., & Ferlie, E. (2010). Staying native: Coproduction in mental health services research. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 23(6), 567–577. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513551011069031

Giroux, H. (1997). Pedagogy and the politics of hope: Theory, culture, and schooling. Westview Press.

Glass, C. R., Kociolek, E., Wongtriat, R., Lynch, R. J., & Cong, S. (2015). Uneven experiences: The impact of student-faculty interactions on international students’ sense of belonging. Journal of International Students, 5(4), 353–367.

Gordon, D. (2015). Trauma and second language learning among Laotian refugees. Journal of Southeast Asian American Education and Advancement, 6(1), 1–15.

Hammond, Z. (2014). Culturally responsive teaching and the brain: Promoting authentic engagement and rigor among culturally and linguistically diverse students. Corwin.

Heng, T. T. (2017). Voices of Chinese international students in USA colleges: ‘I want to tell them that … .’ Studies in Higher Education, 42(5), 833–850. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1293873

Herman, J. L. (1997). Trauma and recovery. Basic Books.

Hodges-Wu, J., & Zajicek-Farber, M. (2016). Addressing the needs of survivors of torture: A pilot test of the psychosocial well-being index. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 15(1), 71–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2016.1171941

Holmkvist, E., Sullivan, K. P., & Westum, A. (2018). Swedish teachers’ understandings of post-traumatic stress disorder among adult refugee-background learners. In S. Shapiro, R. Farrelly, & M. J. Curry (Eds.), Educating refugee-background students (pp. 177–190). Multilingual Matters.

Hoover, S. M., Luchner, A. F., & Pickett, R. F. (2016). Nonpathologizing trauma interventions in abnormal psychology courses. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 17(2), 151–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2016.1103109

Horsman, J. (1998). But I'm not a therapist! The challenge of creating effective literacy learning for survivors of trauma. Australian Council for Adult Literacy 21st National Conference: Literacy on the line. Conference proceedings. https://www.literacyresourcesri.org/jenny.tesol.html

Ibrahim, H., Ertl, V., Catani, C., Ismail, A. A., & Neuner, F. (2018). The validity of posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) as screening instrument with Kurdish and Arab displaced populations living in the Kurdistan region of Iraq. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 259. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1839-z

Ilyas, M. (2019). Survivors of trauma in survival language programs: Learning and healing together. The TESOLANZ Journal, 27, 29–43.

Isserlis, J. (2009). Trauma and learning—What do we know, what can we learn? Low Educated Second Language and Literacy Acquisition. Proceedings of the 5th Symposium, Banff.

Jelinek, L., Jacobsen, D., Kellner, M., Larbig, F., Biesold, K. H., Barre, K., & Moritz, S. (2006). Verbal and nonverbal memory functioning in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 28(6), 940–948. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803390591004347

Johnsen, G. E., & Asbjornsen, A. E. (2009). Verbal learning and memory impairments in posttraumatic stress disorder: The role of encoding strategies. Psychiatry Research, 165(1–2), 68–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.01.001

Kessler, R. C., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Bromet, E. J., Cardoso, G., Degenhardt, L., de Girolamo, G., Dinolova, R. V., Ferry, F., Florescu, S., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., Huang, Y., Karam, E. G., Kawakami, N., Lee, S., & Koenen, K. C. (2017). Trauma and PTSD in the WHO world mental health surveys. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(5), 1353383. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2017.1353383

Khasinah, S. (2014). Factors affecting second language acquisition. Englisia, 1(2), 256–279.

Kincheloe, J., McLaren, P., & Steinberg, S. R. (2014). Critical pedagogy and qualitative research: Moving to the bricolage. In S. R. Steinberg & G. S. Cannella (Eds.), Critical qualitative research reader (pp. 14–32). Peter Lang Publishing.

King, J., & Smith, L. (2017). Social anxiety and silence in Japan’s tertiary foreign language classrooms. In C. Gkonou, M. Daubney, & J. M. Dewaele (Eds.), New insights into language anxiety (pp. 91–109). Multilingual Matters.

Knipscheer, J. W., Sleijpen, M., Mooren, T., Ter Heide, F. J., & van der Aa, N. (2015). Trauma exposure and refugee status as predictors of mental health outcomes in treatment-seeking refugees. Bjpsych Bulletin, 39(4), 178–182. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.114.047951

Koenen, K. C., Ratanatharathorn, A., Ng, L., McLaughlin, K. A., Bromet, E. J., Stein, D. J., Karam, E. G., Meron Ruscio, A., Benjet, C., Scott, K., Atwoli, L., Petukhova, M., Lim, C. C. W., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Al-Hamzawi, A., Alonso, J., Bunting, B., Ciutan, M., & Kessler, R. C. (2017). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the World Mental Health Surveys. Psychological Medicine, 47(13), 2260–2274. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717000708

Kosny, A., MacEachen, E., Lifshen, M., & Smith, P. (2014). Another person in the room: Using interpreters during interviews with immigrant workers. Qualitative Health Research, 24(6), 837–845. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732314535666

Kostouros, P., Scarff, B., Millar, N., & Crossman, K. (2022). Trauma-informed teaching for teachers of English as an additional language. Traumatology. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000381

Lawless, B., & Chen, Y. W. (2018). Developing a method of critical thematic analysis for qualitative communication inquiry. Howard Journal of Communications, 30(1), 92–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/10646175.2018.1439423

Lima, E. P., Vasconcelos, A. G., Berger, W., Kristensen, C. H., Nascimento, E. D., Figueira, I., & Mendlowicz, M. V. (2016). Cross-cultural adaptation of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist 5 (PCL-5) and life events checklist 5 (LEC-5) for the Brazilian context. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 38(4), 207–215. https://doi.org/10.1590/2237-6089-2015-0074

Lindauer, R. J., Olff, M., van Meijel, E. P., Carlier, I. V., & Gersons, B. P. (2006). Cortisol, learning, memory, and attention in relation to smaller hippocampal volume in police officers with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 59(2), 171–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.033

Liu, W. M., Liu, R. Z., Garrison, Y. L., Kim, J. Y. C., Chan, L., Ho, Y. C. S., & Yeung, C. W. (2019). Racial trauma, microaggressions, and becoming racially innocuous: The role of acculturation and White supremacist ideology. American Psychologist, 74(1), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000368

Louzao, J. (2018). Unconscionable input: Confronting the impacts of adverse childhood experiences on English language learners. Highline Language Research Journal, 2018, 1–31.

Lutzker, P. (2014). Attunement and teaching. Research on Steiner Education, 5, 65–72.

Maercker, A., & Horn, A. B. (2013). A socio-interpersonal perspective on PTSD: The case for environments and interpersonal processes. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 20(6), 465–481. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1805

Marucci, E., Oldenburg, B., & Barrera, D. (2018). Do teachers know their students? Examining teacher attunement in secondary schools. School Psychology International, 39(4), 416–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034318786536

McLachlan, D. A., & Justice, J. (2009). A grounded theory of international student well-being. Journal of Theory Construction & Testing, 13(1), 27.

McPherson, P. (1997). Investigating learner outcomes for clients with special needs in the Adult Migrant English Program. Macquarie University.

Montero, M. K. (2018). Narratives of trauma and self-healing processes in a literacy program for adolescent refugee newcomers. In S. Shapiro, R. Farrelly, & M. J. Curry (Eds.), Educating refugee-background students (pp. 92–106). Multilingual Matters.

Morrison, A., Rigney, L. I., Hattam, R., & Diplock, A. (2019). Toward an Australian culturally responsive pedagogy: A narrative review of the literature. University of South Australia.

National Center for PTSD. (2013). Using the PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) [Fact sheet]. www.ptsd.va.gov

Nelson, C. D., & Appleby, R. (2015). Conflict, militarization, and their after-effects: Key challenges for TESOL. TESOL Quarterly, 49(2), 309–332. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.187

Norton, B. (2013). Identity and language learning: Extending the conversation (2nd ed.). Multilingual Matters.

Orygen. (2017). Under the radar: The mental health of Australian university students. Orygen.

Oxford, R. L. (2016). Toward a psychology of well-being for language learners: The “EMPATHICS” vision. In P. D. MacIntyre, T. Gregersen, & S. Mercer (Eds.), Positive psychology in SLA (pp. 10–90). Multilingual Matters.

Oxford, R. L. (2017). Anxious language learners can change their minds: Ideas and strategies from traditional psychology and positive psychology. In C. Gkonou, M. Daubney, & J. M. Dewaele (Eds.), New insights into language anxiety (pp. 177–197). Multilingual Matters.

Pashang, S., Biazar, B., Payne, D. E., & Kaya, Z. (2018). Teaching English as an additional language (EAL) to refugees: Trauma and resilience. In S. Pashang, N. Khanlou, & J. Clarke (Eds.), Today’s youth and mental health: Hope, power, and resilience (pp. 359–378). Springer International Publishing.

Patel, R. S., Elmaadawi, A., Nasr, S., & Haskin, J. (2017). Comorbid Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and opioid dependence (Case Report). Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.1647

Pennycook, A. (2001). Critical applied linguistics: A critical introduction. L. Erlbaum.

Perry, B. D. (2006). Fear and learning: Trauma-related factors in the adult education process. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 110, 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.215

Ryan, J., & Viete, R. (2009). Respectful interactions: Learning with international students in the English-speaking academy. Teaching in Higher Education, 14(3), 303–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510902898866

Schreiner, L. A. (2017). The privilege of grit. About Campus, 22(5), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/abc.21303

Silove, D. (2013). The ADAPT model: A conceptual framework for mental health and psychosocial programming in post conflict settings. Intervention, 11(3), 237–248.

Silove, D., Steel, Z., & Bauman, A. (2007). Mass psychological trauma and PTSD: Epidemic or cultural illusion? In J. Wilson & C. S. Tang (Eds.), Cross-cultural assessment of psychological trauma and PTSD (pp. 319–336). Springer.

Şimşek, E., & Dörnyei, Z. (2017). Anxiety and L2 self-images: The “anxious self.” In C. Gkonou, M. Daubney, & J. M. Dewaele (Eds.), New insights into language anxiety (pp. 51–70). Multilingual Matters.

Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. Zed Books.

Smyth, J. (2011). Critical pedagogy for social justice. Continuum International Publishing.

Smyth, J., Down, B., McInerney, P., & Hattam, R. (2014). Doing critical educational research: A conversation with the research of John Smyth. Peter Lang Publishing.

Supin, J. (2016). The long shadow: Bruce Perry on the lingering effects of childhood trauma. The Sun, 491, 4.

Theorell, T., & Sondergaard, H. P. (2004). Language acquisition in relation to cumulative posttraumatic stress disorder symptom load over time in a sample of resettled refugees. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 73, 320–323. https://doi.org/10.1159/000078849

Thurman, J. (2018). Affect. In J. Thurman (Ed.), The TESOL encyclopedia of English language teaching (pp. 1–6). Hoboken: Wiley.

Tinto, V. (1987). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. University of Chicago Press.

Tinto, V. (2015). Through the eyes of students. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 19(3), 254–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025115621917

Tweedie, M. G., Belanger, C., Rezezadeh, K., & Vogel, K. (2017). Trauma-informed teaching practice and refugee children: A hopeful reflection on welcoming our new neighbours to Canadian schools. BC TEAL Journal, 2(1), 36–45.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin Books.

Vasterling, J. J., Duke, L. M., Brailey, K., Constans, J. I., Allain, A. N. J., & Sutker, P. B. (2002). Attention, learning, and memory performances and intellectual resources in Vietnam veterans: PTSD and no disorder comparisons. Neuropsychology, 16(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0894-4105.16.1.5

Wallace, D. (2020). Post-traumatic stress disorder in Australia: 2020. Australasian Psychiatry, 28(3), 251–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856220922245

Weathers, F. W., Litz, B. T., Keane, T. M., Palmieri, P. A., Marx, B. P., & Schnurr, P. P. (2013). The PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). https://www.ptsd.va.gov/

Wilbur, A. (2016). Creating inclusive EAL classrooms: How language instruction for newcomers to Canada (LINC) instructors understand and mitigate barriers for students who have experienced trauma. TESL Canada Journal, 33(10), 1–19.

Wilson, V. (2022). Liberty, equality, fraternity: Trauma-informed English language teaching to adults The Paris Conference on Education 2022. Paris. https://doi.org/10.22492/issn.2758-0962.2022.19

Wilson, V. E. (2023). Nothing about us without us: An investigation into trauma-informed teaching of English tospeakers of other languages at universities in south-east Queensland. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Queensland]. University of Queensland]. https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:87822a6.

Woodrow, L. (2006). Anxiety and speaking English as a second language. RELC Journal, 37(3), 308–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688206071315

Zinn, D., & Rodgers, C. (2012). A humanising pedagogy: Getting beneath the rhetoric. Perspectives in Education, 30(4), 76–87.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the two anonymous reviewers at Australian Educational Researcher for their constructive feedback. Thanks and acknowledgements to the following academics for their rigorous review and feedback on all aspects of this study: Professor Loshini Naidoo (Centre for Educational Research, Western Sydney University). Dr Sue Ollerhead (Senior Lecturer, Languages and Literacy Education; Director, Secondary Education Program; Lifespan Health and Wellbeing Research Centre, Macquarie University). Dr Adriana Diaz (Director of Teaching, Spanish Major; Senior Lecturer, School of Languages and Cultures, University of Queensland). Dr Jemma Venables (Program Lead, Master of Social Work Studies, University of Queensland).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This research was partially supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program Fee Offset Scholarship granted to the lead researcher. Additional partial support was granted to the lead researcher by the University of Southern Queensland’s Academic Development and Outside Studies Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VW 90%, RLB 5%. JD 2.5%, SH 2.5%. The latter three members of the team provided oversight, guidance and review at all stages of the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

None.

Ethical approval