Abstract

In this chapter, positive education is reframed using advances in understanding through trauma-informed perspectives for schools educating students impacted by trauma and systemic educational disadvantage. In order to de-silo trauma-informed teaching and positive education, trauma-aware perspectives are first introduced, including priorities for intervention arising from a systematic review of trauma-aware teacher practice models. Next, positive education is repositioned as a developmental step for teacher practice to fortify wellbeing strategies within the classroom. Then, recommendations are provided, giving guidance for how teachers can begin this practice within their own schools. The chapter concludes with recommendations to support teacher wellbeing in the face of secondary traumatic stress, vicarious effects of childhood trauma, and workplace burnout.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Teachers often witness students who act out and show hyper-aroused behaviours including escalated stress responses, low frustration tolerances, aggressive and loud behaviours, and teachers also witness students who act in and show hypo-aroused behaviours such as withdrawal, silent refusal, freezing up, and giving up. Students who appear to struggle, resist, or refuse to learn in classrooms are often given labels such as “attention-seeking”, “oppositional”, “power-hungry”, or “disengaged”. These labels are often given by well-meaning teachers who desperately want their students to learn, but do not understand the underlying causes of the students’ behaviours and possible pathways towards successful classroom intervention.

Such behaviours often arise from children who have had one or more traumatising experiences (National Child Traumatic Stress Network, 2014). Trauma-aware practice for teachers emerged to help teachers to better understand why students were acting out and/or acting in within their classrooms (de Arellano, Ko, Danielson, & Sprague, 2008; Downey, 2007), accompanying urgent calls for schools to become trauma-sensitive in their teacher practice, school policy, and pastoral care (Cole et al., 2009). It was within this province of empirical investigation (Berger, 2019), teacher practice models (Wolpow, Johnson, Hertel, & Kincaid, 2009), and policy recommendations (Howard, 2019; Ko et al., 2008) that the well-meaning professionals who desired to assist schools to better meet the unmet and complex needs of their students evolved. However, for the past 20 years, the research and practice of trauma-aware pedagogies in schools arose within a silo of trauma-aware practices, which focused on managing the difficulties that arise from trauma, with scant discussion or introduction of the topic of wellbeing for these same students. The field was exclusively focused upon healing in the classroom—and did not focus on the possibility of the new science of wellbeing and growth of psychological resources within the classroom (Seligman, Ernst, Gillham, Reivich, & Linkins, 2009).

Positive education arose within a separate silo, focusing on integrating positive psychology interventions within schools (Seligman et al., 2009), with little understanding of or acknowledgement of trauma aware practices. This is understandable, considering that most positive psychology interventions that were applied within education were tested with normally functioning individuals, tested with student samples that excluded student cohorts who were classified as trauma-affected or were specifically parsed for adverse childhood experiences (Waters, 2011). Over the past decade, the field of positive education has steadily grown (White & Kern, 2018), and yet trauma-aware approaches have mostly been absent in the positive education discourse (Brunzell, Stokes, & Waters, 2016b).

These silos have created considerable confusion for teachers, who are already overburdened and sometimes dealing with their own secondary trauma responses. In our research and its applications for pedagogical practice, teachers on both sides of this divide are frustrated and urgently seeking answers for how to teach and care for their struggling students (Brunzell, Stokes, & Waters, 2018). Many teachers who are trying to adhere to trauma-aware approaches feel a desire to effectively integrate positive education and do not know how—or worse, are told by their school leaders that there is no room in the busy curriculum nor is wellbeing a priority in their school’s strategic planning. On the other side of this coin, teachers who were only doing positive education in trauma-affected classrooms are facing failure when their highly escalated students do not sit still to practice mindfulness, learn about their character strengths, or engage or benefit from practices that seemingly ought to be helping.

This chapter advocates for a trauma-informed positive education approach for educators and researchers who believe that there can be an integrated, developmental approach between these two paradigms. In time-poor schools where teacher professional learning time is at premium, most schools do not have the option to prioritise one over the other. Instead, schools are best served when schools gain understandings that there can be one professional learning journey to support students who need wellbeing the most.

Trauma-Aware Practice for Teachers

Trauma is often defined by the overwhelming view that the world is no longer good and safe. Type 1 trauma describes a one-time event (e.g., natural disasters, community events, loss of a loved one) when the child unexpectedly must contend with the adverse event. Often, the child receives adequate care and support through family and community actions, helping the child to restore the perception that the world is indeed good and safe. Such events bring little shame or guilt, as they can happen to any family, regardless of their socio-economic circumstances, situation, or background. In contrast, Type 2 trauma, often called relational trauma, can have far more distressing and far-reaching consequences (Brunzell et al., 2015a). Type 2 trauma describes ongoing abuse and/or neglect from adults known to the child. Relational trauma often occurs repeatedly over time. As such traumas are more likely to arise from factors such as generational poverty, systemic institutional childhood abuse, or family violence and the effects of that violence in communities, the child often lacks support from the family, school, and community. The child often feels great shame, guilt, and isolation.

Depending on the national context, trauma-aware practice in schools is also referred to as trauma-sensitive or trauma-informed. While some countries (e.g., the U.S. and the U.K.) mostly reserve the term trauma-informed to refer to clinical and therapeutic work with individuals and employ trauma-aware for use in schools, other countries (e.g., Australia) have yet to make the clear distinction between these terms (Cole et al., 2005). This chapter uses the term trauma-aware when discussing teachers and teachers’ own transformation when learning about these approaches and uses the term trauma-informed when discussing the evidence to support these practice models to acknowledge the empirical lineage of the evidence.

Trauma-aware teachers are teachers who understand that childhood trauma can have long-lasting negative impacts on a child’s learning and education trajectory to higher education and future professional pathways. Understanding trauma’s impacts on the biological, neurological, and cognitive resources required for successful learning is essential for effectively assessing why a child may be having in maladaptive ways, what unmet needs this child is trying to meet, and how a teacher can choose an intervention pathway to help the child meet those needs in healthy ways within the classroom (Wolpow et al., 2009).

The causes of childhood trauma are systemic, complex, and difficult to fully assess. The term complex unmet needs can be helpful to trauma-aware teachers as they begin to understand the physical, emotional, cognitive, and spiritual needs of their students (Brunzell et al., 2015a). For instance, when it looks like a child shows loud, escalated behaviour in the classroom because they did not get what they want (e.g., “I want to use the ipad!”), trauma-aware teachers might consider: Is this student acting this way because they have a physical need to move their body and regulate themselves? Is this student acting this way because they have an emotional need to feel safe and successful in the classroom? Is this student acting this way because they have a cognitive need, such as believing that iPad will better facilitate their learning?).

One such need that students have is a need for control. These students have been labelled “power-hungry” and “attention-seeking” for good reason: they are indeed on a quest for power (e.g., empowerment) and attention because they are not successfully meeting those needs outside the classroom. They have learned how to meet these needs in maladaptive ways by turning classrooms into their own environments to master in the only ways they know how. These students are often hypervigilant, scanning the classroom for threats and opportunities as a survival mechanism, often instigating arguments because it is more predictable way for them to gain power and control than to work collaboratively with their peers or accept directions and feedback from a teacher.

These are students who have multiple social and emotional struggles. They can struggle with self-reflection and self-awareness to understand the impacts of their behaviour on others (Schore & Schore, 2008). They struggle with noticing the changes within their own bodies in the rise of escalation and feeling the effects of stress within their own bodies (Murphy, Catmur, & Bird, 2018). And they struggle to understand the effects that their behaviour has on others and the need to restore ruptured relationships. While trauma unaware teachers might address these struggles by lecturing the student on “making better choices”, trauma-aware teachers know that it is up to teachers to deeply reflect on the underlying needs of the child and to create a classroom environment and proactively support positive behaviour within the classroom to facilitate success for students.

Trauma-Informed Pathways for Intervention

Trauma-informed care in schools has evolved into multi-tiered approaches including training for all school staff (Tier 1), consultation between teachers and school wellbeing/welfare staff (Tier 2), and consultation between school wellbeing/welfare staff and external professionals (Tier 3) (Berger, 2019). These multi-tiered approaches acknowledge that trauma not only affects the individual, but also impacts the systems of support surrounding the individual. Teachers within trauma-aware schools know that they cannot do this work alone, and they are best positioned to care for their students when they embrace and connect to community systems of support including parents and carers, external agencies, and community networks.

While a number of trauma-informed models exist (e.g., Bloom, 1995; Downey, 2007; Wolpow et al., 2009), most models incorporate two domains for teacher practice as priorities for teachers to understand and then integrate into learning aims for students: (1) a focus on increasing self-regulatory capacities, including physical and emotional regulation, and (2) a focus on increasing relational capacity for students who resist forming strong and sustainable school-based relationships (Brunzell et al., 2016b).

Domain 1: Increasing Self-Regulatory Capacities

Most trauma-informed practice models for teachers prioritise increasing self-regulatory capacities to help students build self-regulation within their physical body and within their emotional regulation (Brunzell et al., 2016b). When a child perceives that the world is no longer good and safe, they may have an elevated resting heart rate. This in turn increases the reactivity of their arousal and stress-response systems (van der Kolk, 2003). For these children, the threat of ongoing physical and psychological danger requires their bodies to be on high-alert and therefore, they can have difficulties managing stressors caused by unexpected changes or will perceive threat when in fact, there may be no imminent threat present in the classroom.

Moreover, learning is often stressful for these students. Students who can regulate themselves well when faced with the challenge of learning something new can embrace the temporary escalation in the body when the mind is challenged (e.g., Can I do this numeracy problem? If I can’t do it, who can I get support from?)—the brief increase of energy motivates focus and productive action. But this same escalation in the body of other students quickly pushes them over their limit for stress tolerance. They lack effective strategies to manage the escalation, and quickly give up as a protective mechanism to save their reputation in front of their peers, or react quickly without realizing what is happening (e.g., Can I do this numeracy problem? No way! This is stupid! This whole class is stupid!).

Trauma-aware practice encourages teachers to have clear pathways of intervention to strengthen the foundations of classroom culture to increase self-regulatory abilities (Brunzell et al., 2015a), such as students:

-

Having pre-agreed upon strategies for de-escalation when experiencing stress in the classroom (e.g., deep breathing, asking for a two-minute drink of water in the hall, speaking to a trusted friend).

-

Learning about their own stress response and how that stress response can help us understand the shifts in emotion within our bodies.

-

Having opportunities to identify and understand how heated emotions escalate us and work within our bodies.

-

Having a classroom that is predictable and rhythmic by maintaining predictable routines for classroom procedures, student movements, and consistent responses to address classroom adversity.

When teachers revise their classrooms to become places that hold predictable rhythms throughout the day, students begin feeling more empowered to take care of their own needs when escalated, and teachers develop better ability to maintain positive classroom culture (Brunzell et al., 2016b). The opposite is also true: a dysregulated and unpredictable teacher may be mirroring and modelling inconsistency for their students. This can promote a feeling of student uncertainty and prompt ongoing cycles of adverse behaviour.

Domain 2: Increasing Relational Capacity

Students who are trauma-affected often struggle to make and maintain strong classroom relationships. Successful learning requires these relationships. Within a relational context, students must be able to (1) feel connected to and be collaborative with their peers and (2) feel connected to and accept feedback from their teachers. Relational trauma can impact a student’s ability to feel safe and supported in the classroom, and this learning for trauma-aware teachers can be confronting. However, it can also provide valuable answers to questions like: “Why is he treating me like the enemy? I’m the nice adult in his life!” or “Why is she too clingy with me in the classroom? If I ask her to wait a moment when I help others, she has a tantrum or she cries”. Trauma-aware practice encourages teachers to have clear pathways of intervention to increase relational capacities (Brunzell et al., 2015a), such as teachers who:

-

understand the importance of attachment and attunement in the classroom.

-

ground their classroom relationships in unconditional positive regard.

-

see their role in students’ lives as co-regulatory through side-by-side verbal and non-verbal interactions.

-

understand the role of power, power dynamics, and power imbalances within teacher–student relationships.

In our research and practice (Brunzell et al., 2015b; Brunzell, Stokes, & Waters, 2016a), we have witnessed teachers increase their own capacities to relate to their students through the aforementioned guidelines. Without this knowledge, teachers can revert back to ineffective classroom management, which imbalances relational power even further (e.g., “Sit down now! You’re being annoying again, and I need you to make a better choice”), rather than co-regulating the student through deliberate attempts to form a relationship, even when the student is resistant to learning (e.g., kneeling down side-by-side with the student, shoulder to shoulder saying, “I see that you’re struggling. Let’s figure out two strategies to get through this assignment together”).

The trauma-informed literature often describes these two domains as bottom-up interventions which assist the body with bottom-up integration (Perry, 2006). Knowing that trauma is stored within the body (van der Kolk, 2003), teachers require effective strategies to help students understand and regulate their own bodies when pushed into their challenge zone (i.e. the zone of proximal development; Eun, 2019). For teachers, this means that we are not expecting a student to change their behaviour simply by making better choices. Rather, we are assisting the student to increase regulatory and relational connection within their own bodies to maintain positive goals when they feel uncertain or dysregulated.

Repositioning Positive Education in the Classroom

The application of positive education often involves the explicit and implicit teaching of wellbeing through deliberate classroom and school-based strategies that: (1) can be integrated into academic instruction, (2) inform student management in promoting positive student behaviours, (3) contribute to specific curriculum for social emotional learning (SEL) and strengths-based approaches, and (4) fortify broader relationships within schools (e.g., parents, teachers, community supports).

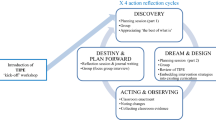

Positive education and trauma-aware practice developed in separate silos. I, along with my colleagues Lea Waters and Helen Stokes, believed that conceptually linking the two areas would help educators understand that both paradigms offer proactive avenues for student support and provide possibilities to improve teacher practice when meeting the complex unmet needs of trauma-affected students (Brunzell et al., 2015b; Brunzell et al., 2016b). The resulting model (see Fig. 8.1) was predicated on Keyes’ (2002) dual-continua model of mental health, which claims that supporting mental ill-health (healing) requires a separate and distinct pathway than increasing wellbeing (growing)—and both are required to help a struggling individual to heal and grow.

The model was also grounded in the belief that strengths are not nurtured solely by focussing on weaknesses (Magyar-Moe, 2009). Rather, trauma-aware teachers benefit from looking to identify and replicate the environmental cues that make moments possible when students identify, understand and employ their strengths, and have their own shining moments of learning.

There are now many ways to posit how wellbeing may be identified and nurtured in individuals (Brunzell et al., 2015a). For instance, teachers might:

-

Prime the day and their lessons with activities that deliberately generate positive emotion and provide opportunities to practice a growth mindset, resilient self-talk and the like.

-

Structure lesson activities to deliberately allow the practice of students’ character strengths.

-

Provide students with opportunities to contribute to others, building a sense of connection and community.

-

Enable students to capitalise and savour small wins and academic successes (especially for students who have not experienced academic success before).

-

Offer students multiple opportunities to identify and practice their character strengths including linking their use to successful pathways beyond formal education.

Importantly, many of these strategies require top-down, cortically modulated capacities. In other words, many of these wellbeing strategies require a well-regulated brain and body to sit in a classroom, learning something new (e.g., identifying one’s self-talk patterns) and then apply that new learning within everyday contexts. If students lack these capacities, as typically occurs for students who have experienced trauma, these activities are less likely to have a positive impact. Concerned teachers have said, “I asked what [student] thought his strengths were, and he said he didn’t have any. I need to address this, but he still won’t participate when we discuss character strengths.” To respond to these and other concerns, our model provides an alternative approach: Trauma-informed positive education (TIPE).

In our model, teachers are first introduced to bottom-up priorities of focussing on increasing self-regulatory capacities (domain 1), including physical and emotional regulation, and focussing on increasing relational capacity (domain 2), before they deliberately focused on a focus on top-down priorities of increasing psychological resources for wellbeing (domain 3). Teachers found that when they worked through the three domains of TIPE, they found students to be ready to learn (resulting from self-regulatory strategies), connected in stronger relationships with their teachers (resulting from relational strategies used by the teacher), and thus, effectively learning wellbeing strategies coming forward from positive psychology interventions in the classroom (Brunzell et al., 2016a; Brunzell, Stokes, & Waters, 2019).

Our work in TIPE suggests that teachers can indeed understand these practice recommendations as developmentally informed and practically possible to shift the cultures of achievement within their classrooms (Brunzell et al., 2016b). Through an integrated bottom-up and top-down approach, teachers can begin to address the unmet needs of students in a variety of ways—and create cultures of healing and growth within the daily life of the classrooms.

Getting Started with Incorporating TIPE into the Classroom

Central to incorporating TIPE into the classroom is the recognition that all students have needs for safety, predictability, and clear expectations within classrooms. However, for teachers who are the first to explore these concepts in their own schools, the challenge can be daunting—especially once teachers realise that no student is managed by just one adult each day. One of the most effective ways to generate a whole-school shift in teacher practice is collective teacher efficacy (Eells, 2011), which refers to a shared belief that when working together, teachers can positively increase student outcomes. Collective teacher efficacy might be initiated by a single teacher incorporating TIPE strategies on their own with the aim of becoming a “lighthouse” of practice within their school. In this process, teachers can gain collective support of their coaches/mentors within the school, increase peer-teacher relationships through peer-observation, feedback and support, all with the aim of showing their school’s leadership a new direction for trauma-informed positive education within their school.

Regardless of whether a teacher is functioning on their own or as part of a collective group, we find that creating safety, routines, and clear expectations (domain 1), complemented by the intentional development of relational capacities (domain 2) and intentional positively oriented structures (domain 3) are beneficial for both teachers and students. Here are two examples of what this looks like in everyday practice through co-regulation and classroom routines.

Co-regulation. Arising from TIPE research is the dual employment of TIPE domain 1 (increasing regulatory abilities) and domain 2 (increasing relational capacity) together when teachers deliberately form co-regulatory relationships. Co-regulation can refer to a developmental way of nurturing classroom relationships (e.g., “As a teacher, I am trying to co-regulate [student] so, one day, he can self-regulate”). It also refers to an intentional way of approaching students when they feel heightened in the classrooms. For instance, instead of confrontationally talking down to students while standing over them or lecturing students in front of their peers on poor behavioural choices, teachers have feedback conversations with students privately, side-by-side, shoulder to shoulder to maintain the student’s self-concept and not embarrass them in front of their peers.

Teachers can more effectively co-regulate students when they themselves feel well-regulated in the face of everyday classroom stressors (Brunzell et al., 2016a). Before teachers experienced TIPE, teachers often reverted to their own escalation, yelling, and unhelpful lecturing when students resisted. Other times, teachers were too passive and afraid to address adverse student behaviour for fear of driving the students deeper into frustration. Beyond feeling their own sense of failure for not facilitating better student outcomes, teachers reported that when mirroring their students’ dysregulation, they were making classroom problems worse.

By practicing strategies of de-escalation (e.g., taking a breath, proactive help-seeking) teachers were modelling domain 1 (increasing self-regulatory abilities) while at the same time increasing these regulatory abilities in themselves. This first step promoted stronger relationships between students and teachers, because teachers both gained credibility as co-regulators while effectively relating to their students and showing them a new way to be in the classroom. Teachers then found their own classrooms primed for more relational interactions and easier to practice unconditional positive regard for students who challenged them, and eventually were able to implement more classroom routines to facilitate self-regulatory strength.

Classroom routines. Routines begin from the moment a student walks through the threshold of the school gates. While some teachers do not yet recognise the importance of intentional, positive student management from the moment the student enters the classroom, TIPE teachers learned that every opportunity to build classroom culture should be employed. The following routines have been adapted to suit many teachers’ practice and the community contexts of their schools.

The class-period might begin with some kind of welcoming routine to reset students from the hour before or the prior class. A circle routine has been effective to build self-regulatory capacity and relational cohesion in classrooms (Brunzell et al., 2015a). A circle represents both a metaphor for community and also serves as a teacher assessment for students’ readiness to learn for the day. A circle routine can be adapted for all ages of students. For example, a circle routine might involve (Brunzell et al., 2015a):

-

A handshake greeting to promote healthy touch, eye-contact, and the positive saying and hearing of one’s name.

-

A short 2-minute circle game (e.g., “pass the clapping rhythm”) to positively prime the room to participate, connect, and generate positive emotions.

-

A statement of classroom (or school) values to anchor the meaning and purpose of coming together to learn.

-

A quick reminder of positive behaviour expectations during the day’s lesson.

-

Any positive announcements such as birthdays or special student celebrations.

-

Concluding with a What Went Well prompt to give students an opportunity to self-reflect and share what has already gone well in the circle routine.

Once this circle routine concludes, students then are prompted into the next academic lesson. Lessons provide the greatest benefits when they have the dual purpose of having a learning aim and a TIPE aim to help students meet their own needs when faced with learning new content and the potential escalation of the stress response if pushed beyond their own window of tolerance (Corrigan, Fisher, & Nutt, 2011). For instance,

-

The lesson might begin with a de-escalation activity before the introduction of new content (e.g. mindful breathing or another transition activity such as a “do-now” challenge problem on the board to get started).

-

The lesson might next have a “hook” to interest students through positive emotion, a character strength that they can use to complete the lesson, or clear connection as to why the learning intention relates to students.

-

Focus might be given to stamina—strategies to help students stay with challenging tasks and strategies to address their own mindsets when learning something new (e.g., identifying mind-hooks in one’s self-talk, activating a growth mindset, recognising when heated emotions arise when faced with learning uncertainty).

-

Giving students regular opportunities to have brain-breaks, which are short, lesson interruptions to renew focus on learning; brain-breaks can include physical movement such as rhythm or clapping games, and they can include mindfulness and sensory tools to integrate somatosensory inputs.

-

A focus on character strengths for students who must have daily exposure to the language and practice of character strengths by highlighting both character strengths within the curriculum (e.g., “Let’s explore how the two characters in the novel are clashing due to their overuse of their strengths”) and to direct student feedback (e.g., “You are really using your strength of courage today to face this challenging chemistry problem”).

Studies suggest that teachers who are effectively holding the rhythm and routines of TIPE practice are effectively nurturing classroom cultures for their trauma-affected students (Brunzell et al., 2015a; Brunzell et al., 2016a). Students come to rely and expect these routines every day, which can eventually lead to their ownership of the learning and setting higher expectations for themselves in the classroom. By passing responsibility back to the students for shared empowerment within classrooms, students can hold teachers accountable to TIPE structures, particularly when students lead the morning circle, create their own brain-breaks, and begin to recognise their own character strengths throughout the school day.

Trauma-Informed Positive Education Changes Us

Within positive education, Norrish and colleagues (2013, p. 150) issued a call for teachers to “live it, teach it, embed it”. This special focus on living it emphasised the importance of deeply reflecting upon and integrating the learning of wellbeing research in our own lives as educators and/or practitioner researchers. To understand wellbeing is to manifest a daily practice of personal wellbeing. While positive education helps teachers and their own wellbeing (Kern, Waters, Adler, & White, 2014), it may be an imperative for trauma-affected students to have living models of wellbeing teaching, coaching, and mentoring them each day.

When it comes to trauma-aware practice in schools, the positive education dictum of living it takes on special importance. Some students already have a highly honed radar for authenticity—in that, they can immediately tell which adults want to be teaching, which adults are truly interested in the content they are teaching, and which adults actually want struggling students in their classroom. Students are quick to see what may trigger escalation in a teacher; and conversely, they can be quick to see which teachers maintain their own unconditional positive regard towards their students in the face of daily stressors. Modelling patient and safe adulthood is what trauma-affected students must witness each day. It may be that if educators working in trauma-affected communities do not take it upon themselves to live TIPE practice, they may be on a devasting pathway to professional burnout.

Left unmitigated, the impacts on trauma’s secondary harmful effects, including vicarious traumatisation and compassion fatigue, leads to about 25% of teachers leaving the profession within a professional that already has 50% workplace turnover (Betoret, 2009; Hakanen, Bakker, & Schaufeli, 2006; Kokkinos, 2007; Pines, 2002). This startling upheaval to the teaching workforce, particularly in trauma-affected schools in communities of systemic disadvantage, requires approaches beyond mitigating burnout. Prior positive psychology interventions have attempted to address teacher wellbeing (see for example Chan, 2013; Siu, Cooper, & Phillips, 2014; Taylor et al., 2015); however, these attempts were not purposely designed to assist teachers to understand the effects of secondary traumatic stressors alongside what teachers can do (1) to effectively teach trauma-affected students and (2) to increase their own workplace wellbeing within trauma-affected school communities.

Trauma-informed positive education may be able to assist both of these concerns. TIPE can be employed as a path of refinement for our teaching, our professional and our own personal journeys. The teachers in the research reflected that they indeed felt like the professionals they strived to be when they could de-escalate in times in moments of student resistance, when they could maintain healthy bonds of attachment to students when relationships were ruptured, and when they could reframe struggling students as students overusing their strengths (Brunzell et al., 2019). Once teachers became trauma-aware, they stopped asking, “What is wrong with this student?” to “What is right with this student—and how can we replicate the enabling conditions for success?”.

Future Directions

TIPE is a relatively new model, and while results are promising, trauma-aware approaches to positive education require future investigation. As an emergent practice model, the developmental claims of the three TIPE domains, the interactions between the domains, and TIPE’s applicability to different cultural and community contexts have not been tested. Future research should endeavour to focus on culturally responsive practice to address Aboriginal and First Nations communities (in the Australian context and around the world), dual-culture/dual-language communities and other contexts where institutional/historical trauma has intergenerationally impacted community systems. For instance, in the work of the Berry Street Education Model (Brunzell et al., 2015a), we are working with Aboriginal childcare agencies to co-create a new model of trauma-informed positive education practice that is culturally informed, culturally respectful, and safe for all members in the community.

Parents and carers should be involved in these efforts, and work is needed on how to best incorporate parent voice, experiences, and aims for their own children within schools. Beyond establishing a shared home-school language to support children and young people, the field should strive to understand how parents and carers can form stronger communication with classroom teachers to adapt successful strategies that students employ in the classroom to their homes, sports fields, clubs, and beyond. The voices and experiences of parents and carers may strengthen the implementation of TIPE in school communities by providing shared understandings and fortifying a shared purpose when addressing the developmental needs of students.

Pre-service teachers and teacher training would benefit from incorporating the research, learnings, and practical experience of TIPE to better prepare future teachers to face the changing nature of communities. In our investigation, teachers new to the profession voiced disappointment that they had not spent any quality time in their teacher preparation programs considering the effects of trauma on learning nor intervention pathways through wellbeing classroom interventions (Brunzell et al., 2016a). These teachers found themselves resorting to ad hoc solutions or worse, knew that their own escalation was making things far worse for their students. Once these teachers learned the science integrating bottom-up and top-down approaches to student engagement, they found their work to be more possible, rewarding, and wanted to share their practice with others.

Conclusions

Students who struggle from systemic concerns of relational trauma from abuse and/or neglect require schools who understand that their mandate to care for students encompasses far more than the national academic curriculum agenda. A positive education that is trauma-aware makes it possible for teachers to effectively reach and teach the students who need wellbeing strategies the most. Trauma-informed positive education is one way that schools and school systems can approach the dual aims of healing and growth in the classroom—alongside the dual aims of student and teacher wellbeing in the classroom.

TIPE is a call for those of us who aspire to the values of positive education to look beneath the surface of what our students are saying and doing in order to employ positive education itself to help meet unmet learning needs within the classroom. TIPE can bolster teachers to stay the course with positive education—and can provide hopeful encouragement to refine and creatively grow pedagogical practice so that all students benefit.

References

Berger, E. (2019). Multi-tiered approaches to trauma-informed care in schools: A systematic review. School Mental Health,11, 650–664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-019-09326-0.

Betoret, F. D. (2009). Self-efficacy, school resources, job stressors and burnout among Spanish primary and secondary school teachers: A structural equation approach. Educational Psychology,29(1), 45–68.

Bloom, S. L. (1995). Creating sanctuary in the school. Journal for a just and Caring Education,1(4), 403–433.

Brunzell, T., Norrish, J., Ralston, S., Abbott, L., Witter, M., Joyce, T., & Larkin, J. (2015a). Berry Street Education Model: Curriculum and classroom strategies. Melbourne, VIC: Berry Street Victoria. https://www.childhoodinstitute.org.au/EducationModel.

Brunzell, T., Waters, L., & Stokes, H. (2015b). Teaching with strengths in trauma-affected students: A new approach to healing and growth in the classroom. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85(1), 3–9.

Brunzell, T., Stokes, H., & Waters, L. (2016a). Trauma-informed flexible learning: Classrooms that strengthen regulatory abilities. International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies, 7(2), 218–239. https://doi.org/10.18357/ijcyfs72201615719.

Brunzell, T., Stokes, H., & Waters, L. (2016b). Trauma-Informed Positive Education: Using positive psychology to strengthen vulnerable students. Contemporary School Psychology, 20, 63–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-015-0070-x.

Brunzell, T., Stokes, H., & Waters, L. (2018). Why do you work with struggling students? Teacher perceptions of meaningful work in trauma-impacted classrooms. Australian Journal of Teacher Education,43(2), 116–142.

Brunzell, T., Stokes, H., & Waters, L. (2019). Shifting Teacher practice in trauma-affected classrooms: Practice Pedagogy strategies within a trauma-informed positive education model. School Mental Health,11, 600–614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-018-09308-8.

Chan, D. W. (2013). Counting blessing versus misfortunes: Positive interventions and subjective wellbeing of Chinese school teachers in Hong Kong. Educational Psychology,33(4), 504–519.

Cole, S., Greenwald, J., Gadd, M. G., Ristuccia, J., Wallace, D. L., & Gregory, M. (2005). Helping traumatized children learn: Supporting school environments for children traumatized by family violence. Boston: Massachusetts Advocates for Children.

Corrigan, F. M., Fisher, J. J., & Nutt, D. J. (2011). Autonomic dysregulation and the window of tolerance model of the effects of complex emotional trauma. Journal of Psychopharmacology,25(1), 17–25.

de Arellano, M. A., Ko, S. J., Danielson, C. K., & Sprague, C. M. (2008). Trauma-informed interventions: Clinical and research evidence and culture-specific information project. Los Angeles, CA & Durham, NC: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress. Retrieved from https://www.nctsn.org/nccts/asset.do?id=1392.

Downey, L. (2007). Calmer classrooms: A guide to working with traumatized children. Melbourne: State of Victoria, Child Safety Commissioner.

Eells, R. J. (2011). Meta-analysis of the relationship between collective teacher efficacy and student achievement (PhD Dissertation, Loyola University). https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/133.

Eun, B. (2019). The zone of proximal development as an overarching concept: A framework for synthesizing Vygotsky’s theories. Educational Philosophy and Theory,51(1), 18–30.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Joiner, T. (2002). Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psychological Science,13, 172–175.

Hakanen, J. J., Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2006). Burnout and work engagement among teachers. Journal of School Psychology,43(6), 495–513.

Howard, J. A. (2019). A systemic framework for trauma-informed schooling: Complex but necessary! Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma,28(5), 545–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2018.1479323.

Kern, M. L., Waters, L. E., Adler, A., & White, M. A. (2014). Assessing employee wellbeing in schools using a multifaceted approach: Associations with physical health, life satisfaction, and professional thriving. Psychology,5, 500–513. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2014.56060.

Kern, M. L., Waters, L. E., Adler, A., & White, M. A. (2015). A multidimensional approach to measuring well-being in students: Application of the PERMA framework. The Journal of Positive Psychology,10(3), 262–271.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior,43(2), 207–222.

Ko, S. J., Ford, J. D., Kassam-Adams, N., Berkowitz, S. J., Wilson, C., Wong, M., Brymer, M. J., & Layne, C. M. (2008). Creating trauma-informed systems: Child welfare, education, first responders, health care, juvenile justice. Professional Psychology, 39,4, 396–404.

Kokkinos, C. M. (2007). Job stressors, personality and burnout in primary school teachers. British Journal of Educational Psychology,77(1), 229–243.

Magyar-Moe, J. L. (2009). Therapist’s guide to positive psychological interventions. Burlington: Academic Press.

Murphy, J., Catmur, C., & Bird, G. (2018). Alexithymia is associated with a multidomain, multidimensional failure of interoception: Evidence from novel tests. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General,147(3), 398–408.

National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2014). Facts and figures, rates of exposure to traumatic events. Retrieved from https://www.nctsnet.org/resources/topics/facts-and-figures.

Norrish, J. M., Williams, P., O’Connor, M., & Robinson, J. (2013). An applied framework for positive education. International Journal of Wellbeing,3(2), 147–161. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v3i2.2.

Perry, B. D. (2006). Applying principles of neurodevelopment to clinical work with maltreated and traumatized children: The neurosequential model of therapeutics. In N. Boyd Webb (Eds.), Working with traumatized youth in child welfare. New York: The Guildford Press.

Pines, A. M. (2002). Teacher burnout: A psychodynamic existential perspective. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice,8(2), 121–140.

Schore, J. R., & Schore, A. N. (2008). Modern attachment theory: The central role of affect regulation in development and treatment. Clinical Social Work Journal,36, 9–20.

Seligman, M. E. P., Ernst, R. M., Gillham, J., Reivich, K., & Linkins, M. (2009). Positive education: Positive psychology and classroom interventions. Oxford Review of Education,35, 293–311.

Siu, O. L., Cooper, C. L., & Phillips, D. R. (2014). Intervention studies on enhancing work wellbeing, reducing burnout, and improving recovery experiences among Hong Kong care workers and teachers. International Journal of Stress Management,21(1), 69–84.

Stokes, H., & Turnbull, M. (2011). The Berry Street Education Model. Melbourne, VIC: Author. Retrieved from www.berrystreet.org.au/Assets/245/1/BerryStreetModel2.pdf.

Taylor, C., Harrison, J., Haimovitz, K., Oberle, E., Thomson, K., Schonert-Reichl, K., & Roseser, R. W. (2015). Examining ways that a mindfulness-based intervention reduces stress in public school teachers: A mixed-methods study. Mindfulness,7(1), 115–129.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2003). The neurobiology of childhood trauma and abuse. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics North America,12, 293–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1056-4993(09)00003-8.

van der Kolk, B. A., & McFarlane, A. (1996). Traumatic stress: The effects of overwhelming experience on mind, body and society. New York: The Guildford Press.

Waters, L. (2011). A review of school-based positive psychology interventions. The Australian Educational and Developmental Psychologist,28(2), 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1375/aedp.28.2.75.

White, M. A., & Kern, M. L. (2018). Positive education: Learning and teaching for wellbeing and academic mastery. International Journal of Wellbeing,8(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v8i1.588.

Wolpow, R., Johnson, M., Hertel, R., & Kincaid, S. (2009). The heart of learning and teaching: Compassion, resiliency, and academic success. Olympia: Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction Compassionate Schools.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Brunzell, T. (2021). Trauma-Aware Practice and Positive Education. In: Kern, M.L., Wehmeyer, M.L. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Positive Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64537-3_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64537-3_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-64536-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-64537-3

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)