Abstract

Cyclic volatile methylsiloxanes (cVMS) have been identified as important gas-phase atmospheric contaminants, but knowledge of the molecular composition of secondary aerosol derived from cVMS oxidation is incomplete. Here, the chemical composition of secondary aerosol produced from the OH-initiated oxidation of decamethylcyclopentasiloxane (D5, C10H30O5Si5) is characterized by high performance mass spectrometry. ESI-MS reveals a large number of monomeric (300 < m/z < 470) and dimeric (700 < m/z < 870) oxidation products. With the aid of high resolution and MS/MS, it is shown that oxidation leads mainly to the substitution of a CH3 group by OH or CH2OH, and that a single molecule can undergo many CH3 group substitutions. Dimers also exhibit OH and CH2OH substitutions and can be linked by O, CH2, and CH2CH2 groups. GC-MS confirms the ESI-MS results. Oxidation of D4 (C8H24O4Si4) exhibits similar substitutions and oligomerizations to D5, though the degree of oxidation is greater under the same conditions and there is direct evidence for the formation of peroxy groups (CH2OOH) in addition to OH and CH2OH.

ᅟ

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ambient nanoparticles (smaller than 100 nm in diameter) can disproportionately affect climate and human health relative to their mass loading in the atmosphere. These particles influence climate by scattering the incoming solar radiation [1–3] and/or serving as cloud condensation nuclei (CCN) [4]. They influence human health by penetrating deep into the respiratory system [5–7]. To better understand these effects, knowledge of the chemical composition is needed [8]. Organic aerosol constitutes a large portion of this matter and most of this contribution is secondary, meaning that it is formed through reaction of gas-phase volatile organic compounds (VOC) with oxidants (OH, O3, NO3) to give semi- or nonvolatile products [8, 9].

Recently, silicon was reported as a frequent component of ambient nanoparticles [10–12]. Measurements with a nano aerosol mass spectrometer (NAMS), which provides quantitative elemental composition of particles in the 10–30 nm diameter range [13–15], showed that Si was often observed in urban and suburban environments but rarely detected in a remote environment [16]. The location dependence suggests that Si in these particles is associated with human activity. One possible source is atmospheric oxidation of cyclic volatile methylsiloxanes (cVMS), which are commonly used in personal care products [17–19]. cVMS are considered to be environmentally acceptable cleaning agents [20] because of their inertness to ozone [21]. Owing to high vapor pressure, they are easily released into the atmosphere where they may react with OH [21] to form semi- or nonvolatile products. An atmospheric transport model for three most common cVMS in personal care products: (octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane, D4; decamethylcyclopentasiloxane D5; and dodecamethylcyclohexasiloxane, D6) is consistent with cVMS as a possible source of nanoparticulate Si [16].

In this work, the molecular composition of secondary aerosol obtained from cVMS oxidation is studied in detail. D5 was chosen as the precursor and D5-derived secondary aerosol was produced through a photo-oxidation chamber (PC) to simulate photo-oxidation in the atmosphere by reaction with hydroxyl radical. Several measurements were taken, including high-resolution ESI-MS, ESI-MSMS, and EI-MS. Previous work used only low-resolution GC-MS analysis, which could only provide partial characterization of the oxidation products [22].

Experimental

Aerosol Formation and Particle Collection

Aerosol was generated in a photo-oxidation chamber (PC) consisting of a 50 L box shaped chamber made of a perfluoroalkoxy copolymer [23]. Before each experiment, the chamber was flushed continuously with clean, dry air for 2–3 d. After flushing, background particle concentrations in the PC were below 100/cm3 and 0.5 μg/m3. The air was cleaned by passing compressed air through charcoal and high efficiency particulate matter air (HEPA) filters to remove organic vapors and particulates, and through silica gel to remove moisture. A scanning mobility particle sizer (SMPS; model 3080/3078; TSI, St. Paul, MN, USA) was used to measure particle size distributions before and during experiments.

D5 vapor was generated by passing clean, dry air with a flow rate of ~700 cpm (cm3/min) over the surface of D5 fluid (CAS no.541-02-6; Gelest, Morrisville, PA, USA) in a gently heated gas flask bubbler. Ozone was generated by passing clean air around a mercury lamp (model no.81-1025-01; BHK Inc., Ontario, CA, USA), and the ozone concentration was monitored with a model 49i O3 analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The gas flow of D5 was sent into the PC along with additional 1 cpm flow of 15–20 ppmv ozone and 240 cpm flow of water vapor, which was created by bubbling air through deionized water. These flows yielded a nominal residence time of 40 min in the PC. Once the gas flow, ozone concentration and relative humidity were stabilized, the reaction was initiated by irradiating the chamber with UV lamps to generate OH from ozone and water. Using the method described by Hall and Johnston [23], the OH mixing ratio for these experiments was estimated to be ~1.5 × 108 cm–3. Particulate matter in the air flow exiting the PC was collected at a flow rate of ~2 Lpm for 20–24 h onto a Teflon coated, glass fiber filter (GF/D, cat. no.1823-025; Whatman GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA) for chemical analysis. Under the conditions used in this study, the secondary aerosol mass concentration was ~60 μg/m3, more than 100 times larger than the background concentration. Generally, 0.3 to 0.5 mg of aerosol was collected in each experiment for analysis. In all experiments, background aerosol samples were collected prior to the injections of reactants to identify and eliminate any artifacts.

After particle collection, the filter was sonicated for 1 h with ~8 mL acetonitrile (ACN) (cat. no. 75-05-8; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) and the resulting solution was filtered through a polyvinylidenedifluoride (PVDF) filter (cat. no. 6747-2504, GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The filtered solution was then concentrated nearly to dryness (<0.5 mL) with a SpeedVac Concentrator (model SC110A; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Finally, the sample was reconstituted to 1 mg/mL with ACN. Reconstitution with methanol or ACN/H2O 50/50 by volume gave similar mass spectrometry results.

A few experiments were performed by bubbling air through a solution of D4 rather than D5. All other conditions for the experiment remained the same. The D4 concentration in the chamber for these experiments was not estimated, though the aerosol mass loading was similar to the D5 oxidation experiments.

Mass Spectrometry

High resolution electrospray mass spectra (ESI-MS) in both positive and negative ion modes were obtained with Q-Exactive Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with a heated electrospray ionization source (HESI). Samples were injected at a flow rate of 0.5 μL/min with a spray voltage of 3.5 kV and a temperature of 250 °C. Mass spectra were obtained over the range 50–950 m/z with a nominal mass resolving power of 70,000. Typically, data were acquired for 1 min with ~60 spectra averaged. For ESI-MS/MS experiments, a quadrupole mass filter isolated each chosen precursor, with subsequent analysis using collision induced dissociation (CID) with the collision energy adjusted between 10 and 30 eV depending on the precursor ion.

Samples were also analyzed by GC-MS with a Waters GCT Premier high-resolution time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) with a scan range of 50–950 m/z coupled to an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Ionization was performed by 70 eV EI with a source temperature of 180 °C. Chromatographic separation was performed with an Agilent HP-5 column using a 3 μL injection volume and an injection port temperature of 280 °C.

Four separate experiments of D5 oxidation were performed under the conditions given above, and only those ions that were detected by ESI-MS in all four experiments are discussed below. These ions represented ~85% of the total number of ions detected. Ions that were detected in fewer than four experiments generally had very low signal intensities, which may have inhibited detection in some experiments and/or may have compromised accurate m/z measurement.

Results and Discussion

Figure 1 shows mass spectra of D5-derived secondary aerosol from one of the four replicate experiments. Both monomer and dimer products are observed. As described in the Supplementary Information, a few additional experiments were performed with a lower mass loading of aerosol in the PC. The monomer signal intensity appeared to increase relative to the dimer signal intensity when the mass loading was decreased (Supplementary Figure S1), though more work is needed to explore this dependence thoroughly.

Ions observed in all four experiments were further characterized in the following way. First, background peaks from the PC and filter were removed from consideration, as were peaks with <0.5% (positive spectrum) and 0.1% (negative spectrum) relative intensity. This left a total of 190 (positive spectrum) and 233 (negative spectrum) peaks between 50 and 950 m/z. Chemical formulas with theoretical m/z values within ±5 ppm of the measured m/z values were determined with the mass spectrometer software (Xcalibur). Reasonable formulas were selected based on the following general criteria: (a) C0-10H1-30O1-20Si1-5 for monomers and C10-20H30-60O10-30Si5-10 for dimers, (b) up to 1 Na atom for peaks in the positive ion spectrum, and (c) H/C atomic ratio between 2.7 and 3.8.

Of the original 190 peaks in the positive spectrum, 154 peaks (81%) were assigned a reasonable single formula based on the above criteria. Of the original 233 peaks in the negative spectrum, 203 peaks (87%) were assigned a single, reasonable formula. The average mass difference between measured and theoretical m/z for peak assignments was 1.28 ppm. The majority of the assigned peaks in the positive ion spectrum (72%) contained one Na atom. Additionally, there was no evidence for multiply charged peaks. Only 30 peaks from the positive spectra and 26 peaks from the negative spectra could not be assigned a reasonable formula, and their relative intensities were generally <1%. Assigned peaks are given in Supplementary Table S1 of the Supplementary Information. The mass weighted signal intensity fractions (MIF) [24] of these ions showed that the average O/Si atomic ratio increased from 1 in D5 to ~1.3 in the oxidized aerosol, whereas the C/Si atomic ratio decreased from 2 to ~1.7 under the experimental conditions used in this study.

Peak assignments from the positive and negative ion spectra were combined, and redundancies due to charge (assuming MH+, MNa+, M-H–) and isotopic substitution were removed, giving 135 unique molecular formulas for the (neutral) products. The products were divided into three types: fragmented products, unsaturated products, and saturated substituted products. Fragmented products were defined as those where the siloxane ring had to be broken, i.e., silicon numbers of 1–4 (monomers) or 6–9 (dimers); representative examples are C8H24O4Si4 and C10H32O8Si6. Unsaturated products were defined as those having silicon numbers of 5 (monomers) or 10 (dimers) but with an H/C atomic ratio less than 3, indicating the presence of unsaturated functional group(s); representative examples are C9H26O8Si5 and C18H52O12Si10. Saturated, substituted products were defined as those having silicon numbers of 5 (monomers) or 10 (dimers), but H/C ≥3 and O/Si >1; representative examples are C9H28O7Si5 and C18H54O11Si10. Under the conditions of these experiments, more that 95% of the total mass weighted signal intensity was encompassed by fragmented and saturated products (Supplementary Table S2). Therefore, only these two product types are discussed below.

Fragmented Oxidation Products of D5

A total of 58 neutral fragmented products were assigned. The molecular formulas suggest the presence of both cyclic and linear siloxane structures with different numbers of subunits, e.g., D2, D3, D4, L2, L3, L4 (D = cyclic; L = linear) with various fragmentations and substitutions, e.g., loss of a CH3 group, substitution of an OH group for a CH3 group, etc. (see Supplementary Table S3). Supplementary Figure S2 gives the positive ESI mass spectrum of pure D5 as a control. Several fragmentation peaks are observed, some examples being 355.069 m/z assigned as (CH3)9(OSi)5 + and 297.082 m/z assigned as (CH3)8(OSi)4H+. It is likely that oxidation products of D5 will also fragment during ESI analysis, making it difficult to distinguish whether or not the fragmentation products observed in this work are the result of photo-oxidation or an ESI artifact.

Saturated Oxidation Products of D5

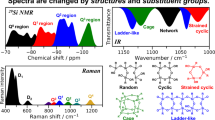

Under the experimental conditions of this study, saturated products represent the majority of the mass-weighted signal intensity (~70%). Relative to D5 and its dimer, these products contain higher amounts of oxygen and lower amounts of carbon and hydrogen. Figure 2 provides a graphical summary of these formulas as a function of carbon to silicon (C/Si) and oxygen to silicon (O/Si) atomic ratios. The changes in O/Si and C/Si ratios between the D5 reactant and its oxidation products indicate the types of reactions that take place [11]. For example, substituting a CH2OH group for a CH3 group increases the O/Si ratio while the C/Si ratio remains constant, i.e., oxidizing (CH3)10(SiO)5 to produce (CH3)10-x(CH2OH)x(SiO)5. Substituting an OH group for a CH3 group decreases C/Si ratio and increases O/Si ratio, i.e., oxidizing (CH3)10(SiO)5 to produce (CH3)10-y(OH)y(SiO)5. For monomers, the assigned product formulas indicate various combinations of OH and CH2OH substitution with up to 6 CH3 groups replaced (Figure 2a). The same types of substitutions are observed for dimers (Figure 2b), but with the additional complication that the two monomers in a dimer can be linked with several species (i.e., O, CH2 and CH2CH2).

Plots of C/Si versus O/Si for saturated products of D5 oxidation in the monomer (a) and dimer (b) regions. Each dot represents an assigned molecular formula of a saturated oxidation product. The arrows in the monomer plot extend from unoxidized D5 and represent the two types of substitution that can occur. The arrows in the dimer plot take into account different possible linkages between monomers

OH Substitution for a CH3 Group

Figure 3a and b show ESI-MSMS spectra of the C9H28O6Si5 product in positive and negative ion modes, which is considered to have one OH substitution for a CH3 group. The positive spectrum in Figure 3a shows the dissociation of the precursor at 373.080 m/z(+), which is assigned as C9H29O6Si5 +, with –2.43 ppm mass accuracy, whereas the negative spectrum in Figure 3b shows the dissociation of the precursor at 371.066 m/z(–), which is assigned as C9H27O6Si5 – with mass accuracy –1.06 ppm. The first neutral loss in positive spectrum is H2O (C9H29O6Si5 + to C9H27O5Si5 +), whereas the corresponding loss in the negative spectrum is CH4 (C9H27O6Si5 – to C8H23O6Si5 –). These products are consistent with protonation of the OH group in the positive spectrum and deprotonation of the OH group in the negative spectrum. Other diagnostic ions are protonated and deprotonated trimethyl silanol, [Si(CH3)3OH + H+] and [Si(CH3)3O–] respectively, neutral loss of Si(CH4)4, and a series of protonated/deprotonated products corresponding to successive loss of siloxane subunits (e.g., loss of C4H12O2Si2 or C6H18O3Si3).

It should be noted that a nearby precursor ion is observed in the positive mass spectrum at 373.043 m/z(+), which is assigned as the unsaturated product C8H25O7Si5 + (–2.17 ppm). Although this ion could lead to some of the products in Figure 3a, several product ions including the first neutral loss cannot be explained by its molecular formula (precursor has fewer carbon atoms than product). Furthermore, when the collision energy is increased from 10 to 30 eV, the product ion signal intensities increase substantially. At the same time, the normalized intensity of the precursor of interest 373.080 m/z(+) decreases by almost a factor of 6 (1.8E6 to 3.4E5), while the normalized intensity for the “impurity” precursor at 373.043 m/z(+) hardly changes at all (8.0E5 to 6.5E5). Taken together, the inconsistency of several product ions with the “impurity” precursor and the disparities in signal intensity suggest that the OH substituted product at 373.080 m/z(+) is the main contributor to the spectrum in Figure 3a and b.

CH2OH Substitution for a CH3 Group

Figure 3c shows the product ion mass spectrum for the 387.098 m/z(+) precursor C10H31O6Si5 + (+0.22 ppm), which corresponds to one CH2OH substitution for a CH3 group. The first neutral loss is H2O, consistent with protonation of the OH functionality. The second and more intense neutral loss is 355.069 m/z(+) (C9H27O5Si5 +, 2.92 ppm), which corresponds to the loss of CH3OH from the precursor. Another diagnostic ion is C4H13OSi+, which corresponds to protonated trimethylsilyl-methanol.

Dimer Linkages by O and CH2

Figure 4a shows the product ion spectrum of the 727.140 m/z(+) precursor assigned as C18H55O11Si10 + (–3.47 ppm), whereas Figure 4b shows an expansion of the product ion spectrum between 350 and 380 m/z(+). Two dimer linkages are possible for the precursor molecular formula. One is linkage by an O atom with all side groups as CH3 (Scheme 1a) and the other by a CH2 group with one side group as OH and the remaining as CH3 (Scheme 1b). The two C9 product ions labeled in black in Figure 4a cannot distinguish between the two linkages since they are expected products of both structures as shown in Scheme 1a and b. However, insight can be gained from other product ions in the spectrum. The first fragmentation from this precursor (C17H51O11Si10 +, –1.90 ppm) corresponds to a neutral loss of CH4, whereas no H2O loss is detected (Figure 4a). Compared with the neutral losses in Figure 3a and c, this observation suggests that very few precursors have an OH group and, therefore, the two siloxane rings are linked by an O atom in most dimers. However, the expansion in Figure 4b shows the presence of very low intensity fragment ions that are consistent with a CH2 linkage. In particular, the C10H29O5Si5 + product ion cannot be obtained from a dimer linked by an O atom (see structures in Scheme 1a and b). Taken together, there is strong evidence that both O and CH2 linkages exist, though products unique to the O linkage have much greater intensity than those unique to the CH2 linkage.

Product ion spectrum of 727 m/z(+): (a) Complete product ion spectrum, and (b) An expansion of 350 to 380 m/z(+). Peaks corresponding to an O linkage are marked with red. Peaks corresponding to a CH2 linkage are marked with blue. Peaks consistent with both are marked in black. (c) Expansion of the product ion spectrum of 795 m/z(+) between 380 and 470 m/z(+). Peaks corresponding to a CH2CH2 linkage are marked with blue

Dimer structures with (a) -O-, (b) -CH2-, and (c) -CH2CH2- linkages. The OH group in (b) could be located anywhere around the siloxane ring. The locations of the two CH2OH groups in (c) can be anywhere on the left hand ring, whereas the location of the OH group can be anywhere on the right hand ring. The C11 product confirms the existence of a CH2CH2- linkage. Other labeled ions are consistent with, but not unique to, this linkage

Dimer Linkage by CH2CH2 (m/z 795.128)

A CH2CH2 linked dimer has been discussed previously as a product of D4 oxidation [22]. Here, there are many precursors having formulas consistent with a CH2CH2 linkage, but it is very difficult to distinguish by MSMS a structure having a CH2 linkage with a CH2OH substitution from one having a CH2CH2 linkage with an OH substitution. Nonetheless, one precursor at 795.128 m/z(+) assigned as C19H56O13Si10Na+ with (–3.18 ppm) provides clear evidence for a CH2CH2 linkage. This precursor must have either a CH2 linkage with three CH2OH substitutions or a CH2CH2 linkage with two CH2OH substitutions and one OH substitution. The key product ion shown in Figure 4c is C11H30O7Si5Na+ (–1.12 ppm), which can only be formed from a precursor having a CH2CH2 linkage as illustrated by the structure in Scheme 1c.

Comparison to Previous Work

GC-MS data are included as Supplementary Information. These data provide the opportunity to check consistency with ESI MSMS analysis and compare with previous work. Similar to the study of Sommerlade [22], GC-MS confirms that major components of D5-derived secondary aerosol are D5 (presumably partitioned to the particle phase and/or bound within dimers), and an oxidation product corresponding to one OH substitution for CH3 (see Supplementary Figure S3).

Our GC-MS results and those of Sommerlade provide evidence for a CH2OH substitution product and the presence of dimers (O and CH2 linked dimers), which is consistent with ESI-MS results, though the full range of products observed with ESI cannot be characterized by GC-MS.

The major products characterized in this work can be explained by OH abstraction of a hydrogen atom from D5 as the initial step. Scheme 2 shows possible formation pathways for several of these products. Formation of the OH substitution product is similar to the reaction sequence proposed by Atkinson [25]. Note that formation of a multiply substituted product does not necessarily require multiple OH abstractions, since an auto-oxidation process based on internal hydrogen rearrangements [26] could lead to several substitutions.

D4-Derived Secondary Aerosol

Secondary aerosol derived from OH oxidation of D4 (C8H24O4Si4) was briefly studied for comparison with D5-derived aerosol. The ESI-MS spectra for D4-derived aerosol showed many more peaks than D5-derived aerosol, especially in the dimer and trimer regions. By applying the analysis procedure as discussed previously for D5, of the original 736 peaks in the positive spectrum, 671 peaks (91%) were assigned a reasonable single formula. Of the original 455 peaks in the negative spectrum, 409 peaks (90%) were assigned a reasonable single formula. The average mass difference between measured and theoretical m/z for peak assignments was 2.56 ppm. After removing redundancies attributable to charge (assuming MH+, MNa+, M-H-), and isotopic substitution, 529 unique molecular formulas for the (neutral) products were obtained, which could be subdivided into fragmented, unsaturated, and saturated products. About 96% of the total products were fragmented or saturated, but more fragmented products were observed for D4-derived aerosol than D5-derived aerosol. MIF analysis showed the O/Si ratio increased from 1 in D4 to ~1.48 in the oxidized aerosol, while the C/Si ratio decreased from 2 to ~ 1.56 for the conditions used in this study.

Saturated products are shown graphically in Figure 5 where C/Si versus O/Si is plotted for each observed molecular formula. Both OH and CH2OH substitutions for CH3 were identified, and relative to D5, a greater fraction of the CH3 groups was found to be oxidized in D4. Furthermore, monomer products having more than eight oxygen atoms added to the D4 molecule were detected, indicating that peroxy groups (CH2OOH) must also be formed.

Plots of C/Si versus O/Si for saturated products of D4 oxidation in the (a) monomer and (b) dimer regions. Each dot represents an assigned molecular formula of a saturated oxidation product. The arrows in the monomer plot extend from unoxidized D4 and represent the two main types of substitution that occur. The arrows in the dimer plot take into account different possible linkages between monomers. Circles represent monomer products where all eight CH3 groups have been substituted. Formulas to the right of the circles (same C/Si but higher O/Si) must contain peroxy groups

Conclusions

The molecular composition of cVMS-derived secondary aerosol was characterized by high performance mass spectrometry. The products can be divided into three types: fragmented products, unsaturated substituted products, and saturated substituted products. Fragmented products arise at least in part as artifacts of electrospray ionization. Saturated substituted products exhibit the highest signal intensities. Based on a mass-weighted intensity fraction analysis, gas phase D5 (O/Si = 1, C/Si = 2) was oxidized to produce aerosol, the detected products of which have an average O/Si ≈ 1.3 and an average C/Si ≈ 1.7 under the conditions studied. Gas phase D4 was oxidized to produce trimers in addition to monomers and dimers, with the detected products having an average O/Si ≈ 1.5 and average C/Si ≈ 1.6 under the conditions studied. ESI-MS/MS analysis of the D5-derived aerosol provided evidence for major substitution types along the siloxane ring and the linkages of two siloxane rings to produce dimers. The results showed that OH and CH2OH substitutions are prevalent, and dimers can be linked by O, CH2 and CH2CH2 groups. D4-derived aerosol gave evidence for the presence of peroxy groups (CH2OOH). GC-MS with EI generally confirmed the ESI analysis, though products were incompletely characterized owing to the greater extent of ion fragmentation.

References

Smith, J.N., Barsanti, K.C., Friedli, H.R., Ehn, M., Kulmala, M., Collins, D.R., Scheckman, J.H., Williams, B.J., McMurry, P.H.: Observations of aminium salts in atmospheric nanoparticles and possible climatic implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107(15), 6634–6639 (2010)

Zhang, R.Y., Wang, L., Khalizov, A.F., Zhao, J., Zheng, J., McGraw, R.L., Molina, L.T.: Formation of nanoparticles of blue haze enhanced by anthropogenic pollution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106(42), 17650–17654 (2010)

See, S.W., Balasubramanian, R., Wang, W.: A study of the physical, chemical, and optical properties of ambient aerosol particles in Southeast Asia during hazy and non-hazy days. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 111, (D10) (2006)

Bzdek, B.R., Johnston, M.V.: New particle formation and growth in the troposphere. Anal. Chem. 82(19), 7871–7878 (2010)

Li, N., Xia, T., Nel, A.E.: The role of oxidative stress in ambient particulate matter-induced lung diseases and its implications in the toxicity of engineered nanoparticles. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 44(9), 1689–1699 (2008)

Inoue, K.I., Takano, H., Yanagisawa, R., Hirano, S., Kobayashi, T., Fujitani, Y., Shimada, A., Yoshikawa, T.: Effects of inhaled nanoparticles on acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide in mice. Toxicology 238(2/3), 99–110 (2007)

Quadros, M.E., Marr, L.C.: Environmental and human health risks of aerosolized silver nanoparticles. J. Air Waste Manage. Assoc. 60(7), 770–781 (2010)

Riipinen, I., Yli-Juuti, T., Pierce, J.R., Petaja, T., Worsnop, D.R., Kulmala, M., Donahue, N.M.: The contribution of organics to atmospheric nanoparticle growth. Nat. Geosci. 5(7), 453–458 (2012)

Kroll, J.H., Seinfeld, J.H.: Chemistry of secondary organic aerosol: formation and evolution of low-volatility organics in the atmosphere. Atmos. Environ. 42(16), 3593–3624 (2008)

Pennington, M.R., Klems, J.P., Bzdek, B.R., Johnston, M.V.: Nanoparticle chemical composition and diurnal dependence at the CalNex Los Angeles ground site. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 117, (2012)

Bein, K.J., Zhao, Y.J., Wexler, A.S., Johnston, M.V.: Speciation of size-resolved individual ultrafine particles in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 110 (D7) (2005)

Phares, D.J., Rhoads, K.P., Johnston, M.V., Wexler, A.S.: Size-resolved ultrafine particle composition analysis - 2. Houston. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 108 (D7) (2003)

Wang, S.Y., Zordan, C.A., Johnston, M.V.: Chemical characterization of individual, airborne sub-10-nm particles and molecules. Anal. Chem. 78(6), 1750–1754 (2006)

Wang, S.Y., Johnston, M.V.: Airborne nanoparticle characterization with a digital ion trap-reflectron time of flight mass spectrometer. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 258(1/3), 50–57 (2006)

Pennington, M.R., Johnston, M.V.: Trapping charged nanoparticles in the nano aerosol mass spectrometer (NAMS). Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 311, 64–71 (2012)

Bzdek, B.R., Horan, A.J., Pennington, M.R., Janechek, N.J., Baek, J., Stanier, C.O., Johnston, M.V.: Silicon is a frequent component of atmospheric nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48(19), 11137–11145 (2014)

Genualdi, S., Harner, T., Cheng, Y., MacLeod, M., Hansen, K.M., van Egmond, R., Shoeib, M., Lee, S.C.: Global distribution of linear and cyclic volatile methyl siloxanes in air. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45(8), 3349–3354 (2011)

Krogseth, I.S., Kierkegaard, A., McLachlan, M.S., Breivik, K., Hansen, K.M., Schlabach, M.: Occurrence and seasonality of cyclic volatile methyl siloxanes in arctic air. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47(1), 502–509 (2013)

Warner, N.A., Evenset, A., Christensen, G., Gabrielsen, G.W., Borga, K., Leknes, H.: Volatile siloxanes in the European Arctic: assessment of sources and spatial distribution. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44(19), 7705–7710 (2010)

Wang, D.G., Norwood, W., Alaee, M., Byer, J.D., Brimble, S.: Review of recent advances in research on the toxicity, detection, occurrence and fate of cyclic volatile methyl siloxanes in the environment. Chemosphere 93(5), 711–725 (2013)

Atkinson, R.: Kinetics of the gas-phase reactions of a series of organosilicon compounds with oH and NO3 radicals and O3 at 297 +/– 2-K. Environ. Sci. Technol. 25(5), 863–866 (1991)

Sommerlade, R., Parlar, H., Wrobel, D., Kochs, P.: Product analysis and kinetics of the gas-phase reactions of selected organosilicon compounds with OH radicals using a smog chamber-mass spectrometer system. Environ. Sci. Technol. 27(12), 2435–2440 (1993)

Hall, W.A., Johnston, M.V.: Oligomer content of α-pinene secondary organic aerosol. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 45(1), 37–45 (2011)

Hall, W.A., Pennington, M.R., Johnston, M.V.: Molecular transformations accompanying the aging of laboratory secondary organic aerosol. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47(5), 2230–2237 (2013)

Atkinson, R., Tuazon, E.C., Kwok, E.S.C., Arey, J., Aschmann, S.M., Bridier, I.: Kinetics and products of the gas-phase reactions of (CH3)4Si, (CH3)4SiCH2OH, (CH3)3SiOSi(CH3)3, and (CD3)3SiOSi(CD3)3with Cl atoms and OH radicals. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 91(18), 3033–3039 (1995)

Crounse, J.D., Nielsen, L.B., Jorgensen, S., Kjaergaard, H.G., Wennberg, P.O.: Autoxidation of organic compounds in the atmosphere. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4(20), 3513–3520 (2013)

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge that this research was supported by the National Science Foundation under grant number CHE-1408455. The Orbitrap mass spectrometer used in this study was purchased under grant number S10 OD016267-01 and supported by grant number 1 P30 GM110758-01, both from the National Institutes of Health. The GCT mass spectrometer used in this study was purchased under grant number CHE-1229234 from the National Science Foundation. The authors thank Andrew Horan for assistance with acquisition and processing of MS data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(PDF 295 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Y., Johnston, M.V. Molecular Characterization of Secondary Aerosol from Oxidation of Cyclic Methylsiloxanes. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 27, 402–409 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13361-015-1300-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13361-015-1300-1