Abstract

Introduction

A significant increase in the incidence of overweight and obesity is observed among children and adolescents. This problem began to occur not only in healthy populations, but also among young diabetics. The aim of the study was to assess the nutritional status of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) compared to those in a control group of healthy subjects as well as to determine the influence of the type of insulin therapy used.

Methods

The case-control study included 169 people aged 9–15 years. The study group (n = 85) consisted of Polish children with T1DM, and the control group (n = 84) consisted of healthy subjects. The assessment of the nutritional status included anthropometric measurements. Analysis of body composition was carried out by bioelectrical impedance analysis. To assess nutritional behavior a questionnaire was used. Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of the Medical University of Białystok (no. R-I-002/168/2017).

Results

Median body mass index (BMI) value in the T1DM group was 19.2 kg/m2 and was statistically significantly (P < 0.05) higher than in the control group (17.8 kg/m2). Normal BMI was found in 90% of the individuals in the CSII group, while in the MDI group it was only 61%. The percentage of fat mass was 19.1% in the T1DM group and 17.6% in the healthy group. The percentage of muscle mass was 36.1% and 34.5%, respectively. The abdominal obesity according to waist circumference (above 90th percentile) turned out to be statistically significant (P < 0.01) and occurred more often in adolescents with T1DM (27%), while in the healthy group it was 12%.

Conclusions

The healthy individuals as well as the majority of the children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus were well nourished. People using personal insulin pumps showed better nutritional status than those using insulin pens.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

The case-control study included 169 children aged 9 to 15 years: the study group (n = 85) contained Polish children with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), and the control group (n = 84) consisted of healthy pupils. The assessment of the nutritional status including anthropometric measurements and analysis of body composition was carried out by bioelectrical impedance analysis. |

The aim of the study was to assess the nutritional status of children and adolescents with T1DM compared to the healthy control group as well as to determine the influence of the type of insulin therapy used. |

What was learned from the study? |

Median body mass index (BMI) value in the T1DM group was 19.2 kg/m2 and was statistically significantly (P < 0.05) higher than in the control group (17.8 kg/m2). |

Normal BMI was found in 90% of the individuals in the CSII group, while in the MDI group it was only 61%. |

Only abdominal obesity according to waist circumference (> 90th percentile) was statistically significant (P < 0.01) and occurred more often in adolescents with T1DM (27%), while in the healthy group it was 12%. |

The majority of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus and healthy individuals were well nourished. Methods for assessing nutritional status are safe and non-invasive, and the results of the study can be used by physicians in diabetic patients, helping them monitor the metabolic control of the disease, which determines the proper somatic development of pediatric patients. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a digital abstract and summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13235321.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus type 1 (T1DM), also known as insulin-dependent diabetes, is a multifactor autoimmune disease; thus, a single factor responsible for occurrence of the disease cannot be determined. It involves chronic hyperglycemia episodes deriving from degradation of beta cells in islets of Langerhans in the pancreas. The most common symptoms are: polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, and unintended weight loss [1]. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) estimates that over 1 million children and adolescents up to the age of 20 struggle with type 1 diabetes [2].

Intensive insulin therapy is the most convenient treatment method, but it requires absolute compliance with certain rules, such as daily reliable self-monitoring of blood glucose levels and individual modification of insulin doses depending on the nutritional value of a meal or on physical activity [3,4,5]. The method of choice is functional intensive insulin therapy conducted as continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) by personal insulin pump (PIP) and multiple daily injections (MDIs) by insulin pen. One of the most important advantages of using PIP is the manner in which it enables better imitation of the physiological rhythm of insulin secretion, improves average blood glucose values and lowers the percentage of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), but most of all it has a positive effect on the quality of life. However, it also requires significant and active involvement on the part of the patient and of his/her family [4, 5]. In Poland, it is the most common method of treatment in the pediatric group [6].

Due to the individual needs of each patient, a universal diet does not exist. Nevertheless, every patient should follow the basic recommendations for proper nutrition. The necessary change in eating habits should include avoidance of products with a high glycemic index, high glycemic load, and easily digestible carbohydrates [7, 8]. At the same time, the diet should be well balanced and provide nutrients that have a beneficial effect on the nutritional status, which determines the proper growth and development of the young body. Over the past few years, an increase in the occurrence of overweight and obesity has been observed, especially among children and adolescents. The tendency to increase body weight exists not only in healthy populations, but also among young diabetics [9,10,11].

The aim of the study was to assess the nutritional status of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus compared to the healthy control group as well as to determine the influence of the type of insulin therapy used. We hypothesized that the nutritional status will be more disturbed in the diabetic group than in the healthy group and that the type of insulin therapy affects nutritional status.

Methods

Study Group

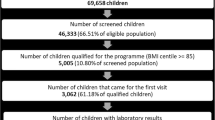

From 280 participants, 169 people aged 9–15 years were chosen and included in our case-control study. The study group (n = 85) contained Polish children with type 1 diabetes mellitus taking part in rehabilitation camps and the control group (n = 84) consisted of healthy pupils from schools. The control group recruitment was based on the medical history interview; there were no symptoms indicating the possibility of diabetes or other disease entities, and thus there was no reason to implement diagnostics. As Fig. 1 shows, the additional selection criteria for inclusion in the study were age (between 9 and 15 years of age) and dwelling in the Warmian-Masurian and Podlaskie Voivodeship. The study was conducted from August 2017 to November 2019.

The study included 95 girls (T1DM group n = 49, control group n = 46) and 74 boys (n = 36 and n = 38, respectively). The T1DM group used different types of insulin therapy: 59 (70%) people used personal insulin pumps, and 26 (30%) used insulin pens.

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of the Medical University of Białystok (no. R-I-002/168/2017). The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study and from their legal guardians.

Anthropometric Measurements

The assessment of the nutritional status consisted of anthropometric measurements (height; weight; circumference of the upper arm, waist and hips; thickness of skin fat folds on the upper arms; hips and shoulder blades). Body height measurements in the Frankfort horizontal plane position with an accuracy of 0.1 cm were made with an InLab height meter (InBody, Seoul, Korea). Size measurements of the waist, hips and upper arm were made with a Gulick tape measure (Baseline 12-1201) with accuracy of 0.5 cm in accordance with the guidelines of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [12]. In 2017, the IDF published findings stating that waist circumference (WC) ≥ the 90th centile in children from 10 to 16 years old points to predisposition to cardiovascular disorders and is the primary diagnostic criterion for metabolic syndrome [13]. For the examination of skin fat folds, a calibrated skinfold caliper (Saehan SH5020) with an accuracy of 0.1 mm was used. The measurements were taken on the non-dominant side of the body, above the triceps muscle of the upper arm vertical grip, under the shoulder blade in a horizontal grip and on the stomach in an oblique grip a quarter distance between the navel and the iliac. The test was repeated three times from each place and then the average of the results obtained was calculated [14].

Body Composition Analysis

Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) assesses body fat by passing a small current through the body and then assessing differences in impedance between fat and lean tissues, which have different electrical properties [15]. Analysis of body composition was carried out by BIA on a BC-1000 device (Tanita, Tokyo, Japan). Measurements of body weight, fat content and muscle mass were made with an accuracy of 0.1 g. To take a reliable measurement, participants were placed on a fast and permitted no physical exertion for a period of 10 h before the measurement. The test was performed in the morning at room temperature. The categorization into low, medium and high body fat content was based on gender, age and values developed by the analyzer producer.

Nutritional Status Indicators

In examination of pediatric patients, body mass index (BMI), one of the most commonly used indicators in the assessment of obesity and malnutrition, should be interpreted in relation to developmental norms included in centile grids. The 10th, 85th and 97th centiles coincide with the limits of underweight, overweight and obesity, respectively [14]. The waist-hip ratio (WHR) allows determining the type of body shape and location of fat accumulation. Waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) is used to assess the distribution of abdominal fat. In the population of children and adolescents with abdominal obesity and an increased risk of metabolic syndrome, the index value is > 0.5 regardless of gender [16].

Questionnaire

To assess nutritional behavior, a questionnaire was created containing questions about the kind and number of meals consumed during the day and frequency of consumption of certain products and product groups such as snacks. The questionnaire was conducted with each participant separately. Moreover, patients were asked to provide the most recent HbA1c test results (taken no more than 3 months before). The test results were used to assess metabolic management. According to the American Diabetes Association recommendations, HbA1c at a level < 7% (53 mmol/mol) is suitable for most children with T1DM [8].

Statistical Analysis

The results were statistically processed using Statistica, a computer program software (version 13 PL; TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). The normal distribution of the studied variables was checked using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Student’s t-test for independent samples was used for analysis of quantitative data, and a non-parametric (Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA) test was used when data were not symmetrically distributed. The existence of relationships between qualitative features was assessed using the chi2 test of independence. In justified cases, an additional V-square test and Yates correction were used. To demonstrate the correlation of two features, Spearman’s correlation coefficient with Bonferroni’s amendment was used. The correlation coefficient (R value) was interpreted on a scale of R = 1—full; 0.9 ≥ R ≥ 0.5—high; 0.5 ≥ R ≥ 0.3—moderate, 0.3 ≥ R ≥ 0.1—weak; R = 0—no correlation. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The minimum (required) number of people in the sample was calculated assuming a maximum error value (11%) and a set confidence level (95%).

Results

The characteristics of the studied groups are summarized in Table 1. Physical development (height and weight) was similar in both groups. Median HbA1c was 7.4% (57 mmol/mol). Significant statistical differences (P < 0.001) were found between HbA1c in the group of children and adolescents using insulin therapy with a pump (7.1%; 57 mmol/mol) compared to those who used pens (8.0%; 64 mmol/mol). The comparison of HbA1c level in both groups depends on gender and is presented in Table 2.

Table 3 presents values and percentage classification of BMI in the T1DM and control group, but also divided into applied insulin therapies. Median BMI value in the T1DM group was 19.2 kg/m2 and was statistically significantly (P < 0.05) higher than in the control group (17.8 kg/m2). Underweight and normal weight were found in 5% and 81% of patients in the study group and in 5% and 77% of the control group, respectively. In the T1DM group 14% were overweight or obese compared to 18% in the healthy group. Percentage distribution of BMI did not differ statistically. BMI in the CSII group (18.4 kg/m2) was statistically significantly (P < 0.01) lower compared to the MDI group (21.3 kg/m2). Statistically significant differences (P < 0.001) were observed between the pen user (21.3 kg/m2) and control groups (17.8 kg/m2). Normal BMI was found in 90% of the individuals in the CSII group, while in the MDI group it was only 61%. Over one third (35%) of pen users and only 3% of persons in the PIP group were overweight. At the same time, only 7% of people using pumps were underweight. Moreover, only single pen users could be classified as obese.

From among all study participants, a group of overweight and obese children and adolescents was identified and divided by the type of insulin therapy. Only abdominal obesity according to WC (above 90th centile) turned out to be statistically significant (P < 0.01) and occurred more often in adolescents in the T1DM group (27%), while in the healthy group it was 12%. Other parameters differed slightly in occurrence frequency between groups. In the diabetes group WHR was higher (1.1 vs. 0.9) and WC was lower (75.0 vs. 80.0 cm) as well as hip circumference (HC) (94.5 vs. 95.0 cm) compared to the control group. No differences were found in WHtR between groups. Increased WHtR, WC and HC occurred statistically (P < 0.01) more often in the group of people using pens than in the group using PIP. The statistically significant associations between the groups are presented in the Fig. 2.

Percentage of people at risk of developing abdominal obesity based on selected parameters (WC, HC, WHR, WHtR). Differences between groups were evaluated by the chi-square test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. HC hip circumference, CSII continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion, MDI multiple daily injections, n number of respondents, WC waist circumference, WHR waist-hip ratio, WHtR waist-to-height ratio

The percentage of fat mass was 19.1% in the group with T1DM and 17.6% in the healthy group. Percentage of muscle mass was 36.1% and 34.5%, respectively. Figure 3 presents a box plot of the percentage of fat and muscle tissue in individual groups by gender. There was no statistically significant difference between the median body fat content in adolescents with CSII (19.1%: girls—22.8%; boys—14.7%) and MDI (18.9%: 24.2%; 17.0%), respectively. The muscle content in the PIP group was 34.8% (girls—33.7%; boys—37.9%), but in the pen group was 39.1% (girls—36%; boys—39.3%). The difference between these groups, as well as between the pen group and the control group, was statistically significant (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively).

Box plot of the percentage of body fat and muscle tissue in the control and study group. Values are expressed as median, lower and upper quartile [Me (Q1–Q3)]. The Kruskal-Wallis test and multiple comparisons of the mean ranks for three groups were used to demonstrate statistical significance. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. CSII continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion, MDI multiple daily injections, n number of respondents

Figure 4 presents a graph illustrating the division of the respondents according to the percentage of body fat mass. Almost 60% of them were characterized by normal body fat content, while the rest had either too low (27% of respondents) or too high (16% of respondents) fat content. About 75% of the people using CSII had normal body fat compared to 50% among those using MDI. High body fat content was observed in 10% of patients using CSII and in 30% in the other group. Statistically significant (P < 0.01) dependence was demonstrated between the percentage of body fat and the occurrence of the disease.

A moderate positive statistically significant correlation between HbA1c and anthropometric measurements such as circumferences (arm, waist and hip; P < 0.001), skinfolds (arm, hip and shoulder; P < 0.001) and indicators (BMI, P < 0.001; WHtR, P < 0.05) and fat mass (P < 0.05) was found.

Table 4 presents types of meal models and a list of products declared as consumed between meals. The respondents from T1DM group usually consumed six or more meals per day (39% in the CSII group, 46% in the MDI group) and five meals per day (34% and 42%, respectively). Compared to the control group, where the three- or four-meal nutrition model (46%) definitely dominated, the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.001). The vast majority of adolescents (> 80%) in the T1DM group responded that every day they ate a first breakfast before school compared to 69% in the control group. The study showed that almost three-fourths of adolescents consumed a meal at school in both the T1DM and healthy group. Statistical significance (P < 0.001) was demonstrated between pen and pump users. Patients from the CSII group often ate snacks such as fruit (71%), sweets (53%) and unsweetened milk drinks (41%). Participants in the MDI group also frequently consumed fruit (65%) and sweets (38%) but chose salty snacks (35%) much more often than sweetened milk drinks (27%). More than half of the children in the control group consumed fruit (57%) and sweets (52%) as snacks between meals.

Discussion

To our knowledge, few papers have focused on assessing the nutritional status of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus, and most of them were not cited in our study because of their small sample size, wide age limits or lack of a control group.

Research presented in 2016 at the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes showed that in the years 2010–2014 the incidence of T1DM increased. It is estimated that currently 18.4 per 100,000 people get this disease in the age group up to 18 years. It has been observed that the majority of new patients are between 10 and 14 years of age [17]. Due to the above reports, our study was conducted in a similar age group. The median age of people with type 1 diabetes mellitus was 12.0 years and 11.0 years in the control group.

The most frequently mentioned factors that have a huge impact on the formation of excessive body weight are the difficulty to adequately manage glucose control, an improper diet rich in animal fats and products with a high glycemic index and low levels of daily physical activity [17, 18]. In patients with T1DM, the anabolic effect of insulin has a significant impact [19]. A connection was found between HbA1c and high accumulation of fat in the abdominal area, which was confirmed in our study, as well as in Ingberg’s study [20, 21]. Good metabolic management is essential not only for normal growth and development in pediatric patients with T1DM, but also for reduced or delayed progression of existing complications [22, 23]. Our research showed median HbA1c was 7.4% (57 mmol/mol). Similar metabolic control was presented in the works of Majewska et al. (7.7%; 61 mmol/mol), Särnblad et al. (7.9%; 63 mmol/mol) and Pietrzak et al. (8.0%; 64 mmol/mol) [24,25,26]. We proved that between the two insulin therapies used, with respect to maintaining good metabolic management there is a definite difference in favor of PIP (7.1 vs. 8.0%; 54 vs. 64 mmol/mol; P < 0.001). However, in our study, we found that girls using PIP had higher HbA1c than boys (7.5 vs. 6.6%), but when comparing both insulin therapies girls had similar results (7.5 vs. 7.7%). Samuelsson et al., in their large population study compiled on the basis of data from the national registry, showed a gender difference—girls had poor metabolic control, i.e., higher HbA1c values [27]. The reason may be that girls have worse metabolic control during adolescence than boys [28]. Among the factors influencing this may be the difference in hormonal changes between the respective genders during this period [29]. Some of the studies have proven that both insulin dosages and HbA1c values are significantly higher in girls [30, 31].

Methods for assessing the nutritional status of children and adolescents make it possible to determine the correct nutritional status or detect disorders at an early stage. In pediatric patients, because the anthropometric measurements described below are dependent on age and sex, they should be referred to as developmental norms [14]. According to the IDF, it is important that the patient is assessed according to local percentile meshes [13]. In Poland, percentile meshes proposed by the World Health Organization are recommended up to the age of 3, whereas for children from 3 to 18 years of age, national standards drawn up on the basis of the OLA and OLAF studies are used. Distributions of anthropometric parameters were prepared for body height, weight, BMI, WC and HC [14].

In our study, the BMI value in the T1DM group was 19.2 kg/m2. Published data of other authors were similar—Maffeis et al. (19.3 kg/m2), Ab El Dayem et al. (20.1 kg/m2) and Lipsky et al. (21.3 kg/m2) [32,33,34]. In recent years, the reliability of the BMI indicator in the assessment of nutritional status has been repeatedly denied. In identifying the risk of developing metabolic disorders by estimating visceral fat mass in children and adolescents aged 7–17 years using magnetic resonance imaging, Brambilla et al. proved that WC and WHtR can be a much more sensitive indicator than BMI [35]. WHtR is used to assess the distribution of abdominal fat in people with excessive body weight [36, 37]. In this study, WHtR was used to assess the occurrence of abdominal obesity in children and adolescents with T1DM, which made it possible to compare the results with the research of Nawarycz et al., who examined > 26,000 healthy children in the Łódź region, aged 7–19 years [37]. The authors showed that a WHtR value > 0.5 can be used as a simple and universal criterion for the initial diagnosis of abdominal obesity among adolescents, in both boys and girls. In Szadkowska’s study central obesity was twice as common in children with diabetes as in the general population [37, 38]. Our research showed that in overweight and obese children with T1DM WHR was 1.1; WC and HC were 75.0 and 94.5 cm, respectively. No differences were found according to WHtR. Average WHtR and WC in Maffeis’s study were 0.44 and 67.8 cm, respectively [32]. Completely different results were received as well by Marigliano et al. (0.39 and 57.5 cm) [39]. This is probably because the authors calculated the averages for the above-listed parameters for the whole group, not only for people with excessive body mass.

In our research the percentage of fat and muscle mass in the T1DM group was 19.1% and 36.1%, respectively. Similar results were presented by Maffeis et al. (fat mass: 18.5%) and with a little divergence by Margaliano et al. (fat mass: 15.0%), Majewska et al. (24.5 and 45.5%, respectively) and Lipsky et al. (fat mass: 27.5%) [24, 32, 34, 39]. In our study, despite similar median percentages of fat mass between the two insulin therapies, after subgrouping by gender, the content was lower in people using CSII, but not statistically significantly so. However, the obtained medians are within the normal range. However, a large spread between the results may be related to the fact that the CSII group was characterized by a lower HbA1c, BMI and percentage of people with excessive fat mass compared to the MDI. Unfortunately, it was not possible to compare muscle mass with results from other authors because of our usage of dissimilar parameters (muscle mass instead of fat-free mass). A statistically significant difference in the percentage of muscle tissue could result from the fact that in the group of boys we had a dispersion of results, especially in those with MDIs. Their higher BMI may confirm that this is an unreliable indicator for people with higher muscle mass, possibly related to greater physical activity. The general conclusion from the comparison of this parameter in healthy participants and with T1DM may indicate that adolescents more often prefer spending their time passively than actively. People with T1DM are often more aware of the impact of physical activity on health [40].

The nutritional status of most respondents was normal, however, 13% of the adolescents with T1DM were overweight. Moreover, 10% of those using CSII and 30% of MDI had too much fat mass. Our research showed that BMI, fat mass and parameters indicating abdominal obesity positively correlated with HbA1c.Assessment of anthropometric parameters among young diabetics should be one of the standard periodic tests. Methods for assessing nutritional status are safe and non-invasive, and the results of the study can be used by physicians in diabetic patients, helping them monitor the metabolic control of the disease, which determines the proper somatic development of pediatric patients. This is why it is worth controlling the nutritional status as a whole, and not just height and weight separately.

The recommendation about the number of meals per day for diabetic children is related to insulin dosage. Therefore, careful meal planning is most important [40]. The introduction of validated mobile medical applications for diabetes care would facilitate appropriate therapeutic decisions and positively impact outcomes, including HbA1c levels and hypoglyemia rates [41]. The diabetics had more main meals and fewer sweetened snacks per day compared to healthy children. Nevertheless, the difference between meals and snacks is difficult to assess, because the overall food composition can be similar [42].

There were a few limitations to our study. First was the small number of participants because the children with T1DM were from two voivodeships and randomly included in this research. Second, the disproportion between the number of persons in the groups with different types of insulin therapy occurred because most of the children use CSII rather than pens. When designing the study we were guided by the data about the number of pediatric patients with T1DM (around 22,000) in Poland and estimates of people using CSII among them (16,600, which is 75% of this group) [6]. However, the relationships observed between features show a huge potential to develop studies on a wider scale and on larger groups. Research will be conducted from this perspective by our team.

Conclusions

The majority of the children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus and healthy individuals were well nourished. Additionally, the study concluded that people using personal insulin pumps had better nutritional status than those using insulin pens. It has been shown that the type of insulin therapy did not affect eating behaviors, including snack selection.

References

World Health Organization. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications: report of a WHO consultation 1999; 1999. https://who.int. Accessed 25 July 2019.

International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas—9th Edition 2019; 2019. https://diabetesatlas.org. Accessed 26 July 2019.

Danne T, Phillip M, Buckingham B, et al. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2018: insulin treatment in children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2018;19:115–35.

Yeh H, Brown TT, Maruthur N, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of methods of insulin delivery and glucose monitoring for diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:336–47.

Malik FS, Taplin CE. Insulin therapy in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Drugs. 2014;16:141–50.

Narodowy Fundusz Zdrowia. NFZ o zdrowiu: cukrzyca. Centrala Narodowego Funduszu Zdrowia, 2019. https://www.nfz.gov.pl/. Accessed Nov 2019.

MacLeod J, Franz MJ, Handu D, et al. Academy of nutrition and dietetics nutrition practice guideline for type 1 and type 2 diabetes in adults: nutrition intervention evidence reviews and recommendations. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117:1637–58.

American Diabetes Association. 13. Children and adolescents: standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:S163–82.

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG, et al. Trends in obesity prevalence among children and adolescents in the United States, 1988–1994 through 2013–2014. JAMA. 2016;315:2292–9.

Olds T, Maher C, Zumin S, et al. Evidence that the prevalence of childhood overweight is plateauing: data from nine countries. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6:342–60.

DuBose SN, Hermann JM, Tamborlane WV, et al. Obesity in youth with T1D in Germany, Austria, and the United States. J Pediatr. 2015;167:627–32.

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Anthropometry Procedures Manual, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_07_08/manual_an.pdf. Accessed 25 July 2020.

International Diabetes Federation. The IDF consensus definition of the Metabolic Syndrome in children and adolescents, 2017. https://diabetesatlas.org. Accessed July 2019.

Kułaga Z, Różdżyńska-Świątkowska A, Grajda A, et al. Percentile charts for growth and nutritional status assessment in Polish children and adolescents from birth to 18 year of age. Stand Med Pediatr. 2015;12:119–35.

Dubiel A. Bioelectrical impedance analysis in medicine. World Sci News. 2019;125:127–38.

Brończyk-Puzoń A, Koszowska A, Bieniek J. Basic anthropometric measurements and derived ratios in dietary counseling: part one. Piel Zdr Publ. 2018;8:217–22.

Pańkowska E. Definition, classification and incidence of type 1 diabetes. In: Pańkowska E, eds. Diabetes: personalization of therapy and patient care. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Lekarskie PZWL; 2017:3–7.

Heyman E, Toutain C, Delamarche P, et al. Exercise training and cardiovascular risk factors in type 1 diabetic adolescent girls. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2007;19:408–19.

Schwartsburd PM. Catabolic and anabolic faces of insulin resistance and their disorders: a new insight into circadian control of metabolic disorders leading to diabetes. Future Sci OA. 2017;3:1–15.

Valerio G, Iafusco D, Zucchini S, et al. Abdominal adiposity and cardiovascular risk factors in adolescents with T1D. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;97:99–104.

Ingberg CM, Särnblad S, Palmér M, et al. Body composition in adolescent girls with type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2003;20:1005–11.

Michaliszyn SF, Shaibi GQ, Quinn L, et al. Physical fitness, dietary intake, and metabolic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2009;10:389–94.

Donaghue KC, Chiarelli F, Trotta D, et al. Microvascular and macrovascular complications associated with diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes. 2009;10:195–203.

Majewska KA, Majewski D, Skowronska B, et al. Serum resistin concentrations in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus—negative relations to body fat mass. Endokrynol Pol. 2014;65:342–7.

Särnblad S, Ingberg CM, Åman J, et al. Body composition in young female adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus. A prospective case-control study. Diabet Med. 2007;24:728–34.

Pietrzak I, Mianowska B, Gadzicka A, et al. Blood pressure in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus—the influence of body mass index and fat mass. Pediatr Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2009;15:240–5.

Samuelsson U, Anderzén J, Gudbjörnsdottir S, Steineck I, Åkesson K, Hanberger L. Teenage girls with type 1 diabetes have poorer metabolic control than boys and face more complications in early adulthood. J Diabetes Complicat. 2016;30:917–22.

Hoffman RP, Vicini P, Sivitz WI, Cobelli C. Pubertal adolescent male–female differences in insulin sensitivity and glucose effectiveness determined by the one compartment minimal model. Pediatr Res. 2000;48:284–388.

Ahmed ML, Conners MH, Drayer NM, Jones JS, Dunger DB. Pubertal growth in IDDM is determined by HbA1c levels, sex, and bone age. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:831–5.

Knerr I, Hofer SE, Holterhus PM, et al. Prevailing therapeutic regimes and predictive factors for prandial insulin substitution in 26 687 children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes in Germany and Austria. Diab Med. 2007;24:1478–81.

Setoodeh A, Mostafavi F, Hedayat T. Glycaemic control in Iranian children with type 1 diabetes mellitus: effect of gender. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79:896–900.

Maffeis C, Fornari E, Morandi A, et al. Glucose-independent association of adiposity and diet composition with cardiovascular risk in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2017;54:599–605.

Abd El Dayem SM, Battah AA. Hypertension in type 1 diabetic patients—the influence of body composition and body mass index: an observational study. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2012;12:60–4.

Lipsky LM, Gee B, Liu A, et al. Body mass index and adiposity indicators associated with cardiovascular biomarkers in youth with type 1 diabetes followed prospectively. Pediatr Obes. 2017;12:468–76.

Brambilla P, Bedogni G, Moreno LA. Crossvalidation of anthropometry against magnetic resonance imaging for the assessment of visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue in children. Int J Obes. 2006;30:23–30.

Dżygadło B, Łepecka-Klusek C, Pilewski B. Use of bioelectrical impedance analysis in prevention and treatment of overweight and obesity. Probl Hig Epidemiol. 2012;93:274–80.

Nawarycz T, Ostrowska-Nawarycz L. Abdominal obesity in children and youth—experience from the city of Łódź. Endokrynol Otył Zab Przem Mat. 2007;3:1–8.

Szadkowska A, Pietrzak I, Szlawska J. Abdominal obesity, metabolic syndrome in type 1 diabetic children and adolescents. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2009;15:233–9.

Marigliano M, Morandi A, Maschio M, et al. Nutritional education and carbohydrate counting in children with type 1 diabetes treated with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion: the effects on dietary habits, body composition and glycometabolic control. Acta Diabetol. 2013;50:959–64.

Wójcik M, Pasternak-Pietrzak K, Fros D, et al. Physical activity of the children and adolescents with diabetes mellitus type 1. Endokrynol Ped. 2014;3:35–44.

Doupis J, Festas G, Tsilivigos C, et al. Smartphone-based technology in diabetes management. Diabetes Ther. 2020;11:607–19.

Siudikienė J, Mačiulskienė V, Nedzelskienė I. Dietary and oral hygiene habits in children with type I diabetes mellitus related to dental caries. Stomatologija. 2005;7:58–62.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants of the study.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study. The journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by the Medical University of Białystok.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Monika Grabia and Renata Markiewicz-Żukowska have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Bialystok, Poland (no. R-I-002/168/2017). The study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study and their legal guardians.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grabia, M., Markiewicz-Żukowska, R. Nutritional Status of Pediatric Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus from Northeast Poland: A Case-Control Study. Diabetes Ther 12, 329–343 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-020-00972-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-020-00972-1