Abstract

Objectives

The current study aimed to examine the mechanisms of change of a compassionate mind training intervention for teachers (CMT-T). In particular, we examined whether changes in the three flows of compassion, fears of compassion, and emotions at work (safe, drive, and threat) mediated the effects of the CMT-T in burnout, depression, anxiety, and stress, and in overall positive affect.

Methods

As part of a two-arm randomized controlled trial and a stepped-wedge design, the study included all participants who completed the 8-week CMT-T intervention either at Time 1 or at Time 2 (n = 103). At pre- and post-intervention, participants completed measures of compassion, fears of compassion, emotional climate in the workplace, burnout, psychopathological symptoms, and positive affect.

Results

Mediation analyses revealed that increases in the flows of compassion and reductions in fears of compassion from others mediated the effects of CMT-T on teachers' depression, anxiety, stress, and burnout levels. In the case of the reduction in stress symptoms from pre- to post-intervention, compassion for self, fears of self-compassion, and fears of receiving compassion from others emerged as significant mediators of this change. The three flows of compassion and fears of compassion (for self and from others) were significant mediators of the impact of CMT-T on changes in teachers’ anxiety levels from baseline to post-intervention. A decrease in fears of compassion from others and an increase in drive emotions mediated changes in depressive symptoms following CMT-T. Concerning burnout, all flows of compassion and fear of compassion from others mediated the changes from baseline to post-intervention. Changes in positive affect following CMT-T were mediated by increases in the flows of compassion, and emotions related to soothing-safeness and drive systems in the workplace. Serial mediational models showed that the effect of CMT-T on teachers’ burnout was partially mediated by reductions in fears of compassion (for self and from others) and stress.

Conclusions

CMT-T effectively improves teachers’ wellbeing and reduces burnout and psychological distress through the cultivation of their ability to experience, direct, and be open to compassion, and the strengthening of the soothing-safeness and the drive systems in the school context.

Preregistration

The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov: identifier, NCT05107323; Compassionate Schools: Feasibility and Effectiveness Study of a Compassionate Mind Training Program to Promote Teachers Wellbeing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

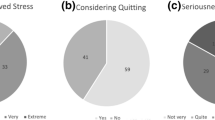

Although a greatly rewarding and valuable role, being a teacher comes with high professional demands (e.g. pupil disruptive behaviours, excessive workload, bureaucracy, time pressures), and can be extremely stressful and have a deleterious impact on teachers’ mental health and wellbeing. At a global scale, burnout, stress, anxiety, and depression are serious mental health problems affecting teachers. Across countries and within all education sectors, high levels of stress and burnout have been reported in teachers (Gray et al., 2017). A recent scoping review highlighted that, when considering clinically significant psychological conditions, the prevalence of burnout in teachers ranged from 25 to 74%, stress ranged from 8 to 87%, anxiety ranged from 38 to 41%, and depression ranged from 4 to 77% (Agyapong et al., 2022). In Portugal, a study on the education sector demonstrated that 75% of teachers present high levels of burnout, with 25% reporting extreme burnout and 84% intending to leave the profession as a result of stress and competitive pressures (Varela et al., 2018). A recent report presenting data collected during the COVID-19 pandemic in Portugal concluded that more than half of teachers revealed signs of psychological suffering (e.g. depression, anxiety, stress, psychological distress) (de Matos et al., 2023).

Teachers’ mental health issues, including stress and burnout symptoms, detrimentally affect their wellbeing and professional outcomes (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009; McCallum et al., 2017; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2015), and are linked to poorer physical health (ESP, 2018; Katz et al., 2016; Varela et al., 2018), implying significant human capital costs and, hence, economic costs (Redín & Erro-Garcés, 2020). Moreover, research has shown that pupil psychological wellbeing (Harding et al., 2019), social and behavioural adjustment (Hoglund et al., 2015; McLean & Connor, 2015), and academic performance and engagement (Hoglund et al., 2015; OECD, 2021) can be negatively impacted by teacher work-related stress and burnout.

The relevance of cultivating social, cognitive, and emotional competencies in teachers and in school settings stems from this widespread mental health crisis in schools. Helping teachers to develop adaptive skills, such as compassion and mindfulness, to better deal with the multiple professional challenges they face (e.g. pupils’ behavioural problems, uncertainty, technological changes) is crucial as it may contribute to improve teacher mental and physical health, while also positively affecting students’ psychological and academic outcomes and promoting a healthy educational environment (Jennings et al., 2019). In this context, several compassion and mindfulness-based interventions aimed at improving wellbeing and mental health in teachers have been developed and evidence gathered for their effectiveness (for reviews, see Hanh & Weare, 2017; Hwang et al., 2017; and Zarate et al., 2019).

Implementing compassion-focused approaches within education settings has been highlighted as particularly important to enhance psychological wellbeing, develop emotional and prosocial skills and ethical behaviour within educational communities, and consequently contribute to nurturing safe, cooperative, and caring learning environments (Gilbert et al., 2020; Lavelle, 2017; Maratos et al., 2022; Roeser et al., 2018; Welford & Langmead, 2015). In this regard, the Compassion in Schools Research Initiative was developed in the UK and in Portugal and evaluated a novel compassion-focused intervention for teachers, the Compassionate Mind Training program for Teachers (CMT-T).

The CMT-T is a Compassionate Mind Training intervention originally developed for teaching staff by Maratos et al. (2019) building upon previous CMT programs for the general population (e.g. Matos et al., 2017), derived from the original CMT (Gilbert & Procter, 2006). Compassionate Mind Training (CMT) is an evolutionary and biopsychosocial evidence-based approach that comprises psychoeducation and a variety of key compassion and mindfulness practices taken from Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT, Gilbert, 2010, 2014, 2020; Gilbert & Procter, 2006), and was developed as an intervention targeting the general public (Gilbert & Choden 2013; Kirby & Gilbert, 2017).

Using a range of mind–body evidence-based practices (e.g. breathing techniques, visualization exercises, behavioural practices), CMT aims to stimulate and promote evolved affiliative care-focused emotions (e.g. safeness, contentment) and motivational systems (e.g. the soothing-affiliative system), and facilitate the down-regulation of threat-focused systems. CMT practices are designed to activate psychological and neurophysiological processes (i.e. stimulate the vagus nerve, balance the autonomic nervous system, recruit several neurocircuits related to compassion; Kim et al., 2020; Porges, 2007; Singer & Engert, 2019) known as beneficial to health, wellbeing, emotion regulation, and social relationships (Gilbert, 2010, 2014, 2020). CMT practices intend to develop mind-awareness, slowing down and grounding in the body, and ultimately cultivate a compassionate self-identity (i.e. compassionate self), that incorporates the qualities of wisdom, courage, caring motivation, and commitment, and embodied to deal with difficulties and daily struggles (e.g. self-criticism) (Gilbert, 2009, 2014; Irons & Beaumont, 2018).

Therefore, CMT focuses on the cultivation of compassion as a prosocial motivation that entails a sensitivity to suffering in self and others with a commitment to try to alleviate and prevent it (Gilbert & Choden 2013). Conceptualized from a CFT evolutionary-focused model, compassion includes two major elements: (i) the preparedness to engage and turn towards suffering and distress in self and others and (ii) the wisdom to understand and implement helpful action. CMT aims to develop mental competencies and physiological states that support these two key interrelated processes of compassion (Gilbert, 2014, 2020). In CMT, the cultivation of a compassionate mind entails the development of competencies, such as sensitivity, sympathy, empathy, distress tolerance, and non-judgment, that allow one to courageously face and engage with difficulties in self and others. In addition, CMT focuses on the development of a variety of skills related to attention, reasoning, mentalizing, and emotional regulation, which facilitate the translation of compassion motives into compassionate actions (Gilbert & Choden 2013; Gilbert, 2010, 2020; Irons & Beaumont, 2018).

Compassion is seen as a dynamic intra- and interpersonal multidimensional process and can thus have different flows: it can be directed outwards, in the form of compassion given to others, or inwards, in the form of compassion received from others, and self-compassion in the form of having compassion for self (Gilbert et al., 2011). CMT focuses on the cultivation of a compassionate mind which includes these three interactive flows of compassion. These flows of compassion (for others, from others, and for self) are highly interactive but can also be independent (Gilbert, 2014; Gilbert et al., 2017). Burgeoning evidence has consistently pointed to a variety of benefits from intentionally developing compassion for oneself and others (e.g. Gilbert, 2017; Kirby et al., 2017a; Seppälä et al., 2017).

In addition to promoting the facilitators of compassion, CMT also targets its inhibitors, also known as fears, blocks, and resistances to compassion (Gilbert, 2014, 2020; Irons & Beaumont, 2018). Fears of compassion can be experienced across the three flows (for others, from others, for self), and hinder the activation of compassion motivational systems, because suffering is either not recognized/avoided or does not result in actions aimed at preventing or alleviating that suffering (Gilbert & Mascaro, 2017; Gilbert et al., 2011). Mounting research has demonstrated that fears of compassion, particularly of self-compassion and of receiving compassion from others, are strongly associated with psychological distress (e.g. depression, anxiety, and stress), and with vulnerability factors, such as self-criticism and shame (Gilbert et al., 2011; Kirby et al., 2019).

Moreover, CMT promotes the understanding of the evolved and complex nature of mind and body, highlighting that the cause of suffering in life and many difficulties people experience are related to evolved processes that have produced our “tricky brains” and are “not our fault” (Gilbert, 2009, 2014). An important part of CMT involves educating people on the evolutionary function of emotions, the multiple nature of emotional states/conflict, and how emotions can be organized into three “systems”, presented as the three-affect regulation systems: threat, drive, and soothing. People can learn how to cultivate the soothing-safeness system and how the activation and development of this system can be helpful in regulating distress and threat/drive-based emotional states, and how to use compassionate mind competencies to promote emotional integration (Gilbert, 2009, 2014; Irons & Heriot-Maitland, 2020).

CMT has been tailored for different non-clinical populations, such as the general public (Irons & Heriot-Maitland, 2020; Matos et al., 2017), mental health professionals (Beaumont et al., 2021), health care educators and providers (Beaumont et al., 2016), and nurses (Beaumont & Martin, 2016; McEwan et al., 2020). Growing research has empirically supported the beneficial effects of CMT in mental and physiological health and prosocial behaviour (for reviews, see Craig et al., 2020; Kirby et al., 2017a; b; and Kirby & Gilbert, 2017).

In the school context, the Compassion in Schools Research Initiative has implemented and tested the feasibility, effectiveness, and international utility of Compassionate Mind Training programs for teachers and for pupils in the UK and Portugal (Maratos et al., 2020; 2024). The Compassionate Mind Training for Teachers (CMT-T) is a six-module group psychological intervention and delivered across eight sessions (2.5 hr each). The sessions address relevant theoretical constructs and experiential exercises, compassion and mindfulness meditation practices, and small group discussions and sharing, along with plenary discussions. A detailed description of the CMT-T can be found in Matos et al., (2022a, 2022b) and in Supplementary Information (SI 1).

In the UK, the original version of the CMT-T was found feasible and well-received by teachers, who found the curriculum and the practices helpful for dealing with emotional difficulties. Moreover, preliminary self-report data revealed significant increases in self-compassion and reductions in self-criticism after the intervention (Maratos et al., 2019). In Portugal, the feasibility and effectiveness of a six-module refined version of the CMT-T were evaluated through a pilot feasibility study (Matos et al., 2022a) and a randomized controlled trial (Matos et al., 2022b). Overall, the CMT-T was found to be feasible and well-received by Portuguese teachers, and preliminary effectiveness data pointed to significant increases in self-compassion, compassion for others, and satisfaction with professional life, and reductions in fears of compassion to others and symptoms of depression, stress, and burnout (Matos et al., 2022a). The CMT-T trial results corroborated the effectiveness of this intervention, with teachers in the CMT-T group showing improvements in self-compassion, compassion to others, positive affect, and heart rate variability, as well as decreases in fears of compassion, anxiety, and depression, when compared to waitlist control group (WLC) participants. Teachers reporting higher baseline levels of self-criticism were the ones revealing larger improvements after the CMT-T. Using a stepped-wedge design (a random and sequential crossover of groups from control to intervention until all groups were exposed; Hemming et al., 2015), this study further revealed that teachers in the WLC group who received CMT-T exhibited additional increases in compassion for others and compassion received from others, and satisfaction with professional life, along with reductions in stress and burnout. These changes were maintained at a 3-month follow-up. Additionally, the international utility of the CMT-T was examined in another study that demonstrated it is a feasible, useful, and effective intervention in cross-cultural educational settings, by addressing and fostering a compassion-based school ethos and by supporting the psychological wellbeing of educators (Maratos et al., 2020).

Nevertheless, in order to improve the effectiveness and parsimony of interventions and establish the association between which processes are targeted and promoted in an intervention and the observed outcomes (Kazdin, 2009), it is critical to identify which processes and mechanisms promoted by an intervention are responsible for treatment-induced changes. Prior research has begun to examine mechanisms of change associated with the impact of CFT and CMT interventions. For example, in a feasibility randomized controlled trial of CFT with patients with a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder, increases in compassion in the CFT group were associated with decreases in levels of depression and of perceived social marginalization (Braehler et al., 2013). In a study exploring mechanisms of a self-help CFT-intervention in a non-clinical sample, Sommers-Spijkerman et al. (2018) reported that the effect of CFT on improving wellbeing and mental health operated through improvements in self-reassurance, regulating positive and negative affect, and reductions in self-criticism (Sommers-Spijkerman et al., 2018). When evaluating an 8-week CMT in a general population sample, another study found that increases in self-compassion from pre-to-post-intervention were associated with changes in self-criticism and wellbeing, and that improvements in compassion from others were linked to changes in wellbeing and emotional outcomes (Irons & Heriot-Maitland, 2020).

In a recent study specifically designed to examine the mechanisms of change of a brief CMT intervention in a general community sample, Matos et al. (2022c) documented that increases in self-compassion, compassion from others, and reductions in fears of compassion (for self, for others, from others) all mediated the effects of CMT on self-criticism and shame. Compassion for the self, compassion received from others, and fears of self-compassion were all found to be significant mediators of CMT-induced changes in depression and stress. Compassion for the self and from others and fears of compassion for self and from others mediated the effect of CMT in safe affect, and self-compassion, fears of compassion for self and for others, and heart rate variability (HRV) mediated changes in relaxed affect. Furthermore, preliminary data from the pilot feasibility study of the CMT-T in a different sample of teachers (Matos et al., 2022a) revealed that fears of compassion for others mediated the impact of CMT-T on teachers’ burnout symptoms and that self-compassion mediated the effect of the CMT-T intervention on psychological wellbeing. Nevertheless, additional research is needed on the mechanisms of change underlying the documented positive effects of CMT-T on wellbeing and mental health reported in the RCT (Matos et al., 2022b). This study would allow to better understand the mechanisms of change of CMT and thus contribute to improve the development and refinement of CMT interventions. Although usually less explored, gathering knowledge on the processes that mediate treatment-induced changes is imperative to make interventions more effective (McCracken & Gutiérrez-Martínez, 2011; Murphy et al., 2009).

Therefore, the current study aimed to examine the mechanisms of change of the CMT-T for burnout, psychological distress, and positive affect at post-intervention. Specifically, this study explored whether changes in the three flows of compassion, fears of compassion, and in safe, drive, and threat emotions at work (resulting from the CMT-T) would mediate changes in burnout, depression, anxiety, stress symptoms, and in feelings of safeness, activation, and relaxation. We hypothesized that the changes occurring after the CMT-T intervention in these outcomes would be mediated by increased competencies for compassion for self, for others, and received from others; decreased levels of fears of compassion for self, for others, and from others; and enhanced soothing-safeness and drive emotions, and diminished threat emotions at work.

Given the relevant role of burnout in teacher mental and physical health (Agyapong et al., 2022; Gray et al., 2017), the previous mixed findings regarding burnout symptoms (Matos et al., 2022a, b), and exploratory data suggesting the mediating role of fears of compassion on the impact of CMT-T on teachers’ burnout (Matos et al., 2022a), two serial mediation models were tested. These serial mediation models aimed to examine whether the impact of the CMT-T intervention on teachers’ burnout levels was mediated by changes in fears of self-compassion and fears in compassion from others and stress symptoms. Our hypothesis was that the intervention would have an effect on teachers’ burnout symptoms not only directly but also by promoting a decrease in their fears of receiving compassion from the self and others, which in turn would reduce their stress levels and consequently their burnout symptoms.

Method

Participants

The sample used for the present study consisted of all participants who completed the CMT-T intervention either at Time 1 or at Time 2 (n = 111). Due to missing data, the final sample included 103 teachers (94 identifying as women (91.3%) and 9 as men (8.7%)), with ages ranging from 25 to 63 years old and a mean age of 50.91 (SD = 7.75). Sixty-eight (66%) participants were married or living with a partner, 17 (16.5%) were single, 14 (13.6%) were divorced, and 4 (3.9%) were widowed. Most of the participants had completed a bachelor’s degree (n = 76; 73.7%), 21 (20.4%) a master’s degree, and 6 (5.8%) a postgraduate specialization degree. Participants were teaching in public schools from Portugal’s centre region for 26.51 (SD = 8.63) years. They were teaching in various grade levels and subject domains, with 11.7% (n = 12) being preschool teachers, 18.4% (n = 19) elementary school, 13.4% (n = 13) middle school, 36.0% (n = 35) high school, and 18.5% (n = 18) special education. The majority of participants qualified as middle or high school grade level teachers in the following content areas: 16.5% (n = 16) languages, 7.2% (n = 7) social and human sciences, 17.6% (n = 17) mathematics and experimental sciences, 2.0% (n = 2) artistic expressions, 2.0% (n = 2) physical education, and information technologies 4.1% (n = 4). Six teachers did not specify further information on these topics. Concerning school setting, participants were recruited from two large middle/high schools located in an urban area (Coimbra; n = 19; 18.4%), in a cluster of schools encompassing two large schools located in a semi-urban area and small schools from rural areas (Sátão; n = 69; 67%), and in a cluster of schools located in an urban area with one large school and other small schools located in urban as well as in rural areas (Viseu; n = 15; 14.6%).

Procedure

The parent study for this project is a pragmatic two-arm randomized controlled trial (RCT), encompassing one experimental group (CMT-T) and one waitlist control group (WLC), using a stepped-wedge design (all groups and participants in groups completed the CMT-T intervention; Matos et al., 2022b). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of the University of Coimbra (CEDI22.03.2018) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier, NCT05107323; Compassionate Schools: Feasibility and Effectiveness Study of a Compassionate Mind Training Program to Promote Teachers Wellbeing). The full procedures of the parent study are described in detail in Matos et al., (2022a, b, c).

Participants were recruited from the teaching staff in public schools (pre- to high school grades) in the centre region of Portugal (Viseu and Coimbra districts). The research team contacted schools’ boards inviting them to take part in the study. Further approval was provided by the board/pedagogic council of the four enrolled schools. An informative recruitment session (lasting for approximately 2 hr) about the study aims and procedures with the teaching staff was conducted by the research team and a leaflet about the study was distributed. Teachers registered their interest to participate (via email) and were then screened for inclusion criteria. Eligibility was defined by the following criteria: (a) being a teacher at the enrolled schools and (b) providing informed consent. Teachers were informed about the voluntary, confidential, and anonymous nature of the study and data protection rights and asked to provide informed consent. A unique and numerical code was generated by participants to assure confidentiality in all assessment tasks. All assessment moments and the CMT-T intervention took place at the schools. Figure 1 illustrates the flow of participants.

In total, 164 teachers from the four schools were interested in participating and met the eligibility criteria. Nine teachers missed the baseline assessment. Following baseline assessment, 155 teachers were randomly assigned to the CMT-T intervention (CMT-T group) or the waitlist control (WLC) group, within each school, using block randomization conducted in a 1:1 ratio (block size = 6). A member of the research team randomly assigned eligible participants within each school to one of the two conditions using a computer-based random allocation process (www.random.org). The CMT-T intervention was delivered to each WLC group after their parallel CMT-T group received the CMT-T (approximately 2 months later). Six groups completed the CMT-T (n per group M = 18). Out of the initial 80 teachers allocated to the CMT-T group (Time 1), five did not attend any session, and nine participants dropped-out (11.25%) due to work schedule incompatibility. From the 75 participants allocated to the WLC group, 29 did not complete the post-intervention assessment moment. The remaining 46 teachers previously allocated to the WLC group were then invited to complete the intervention at Time 2 (equivalent to the same time point as the post-intervention assessment of the CMT-T group). Out of these, 37 received the CMT-T intervention, and nine decided not to take part. At Time 2, there were no dropouts from the intervention.

The Compassionate Mind Training Program for Teachers (CMT-T)

The CMT-T is a compassion-focused intervention designed for teaching staff and delivered in a group format across eight sessions of approximately 2.5 hr each. The CMT-T comprises six modules addressed during the eight sessions. A detailed overview of the CMT-T intervention can be found at Matos et al. (2022b).

The facilitators of the CMT-T intervention were certified clinical psychologists with a PhD degree and CFT/CMT-based clinical intervention experience and one teacher with a PhD degree, CFT training, and certified mindfulness teacher training. Two lead facilitators led each training group. rigorously following the CMT-T manual.

Measures

Demographics and professional questionnaire: Sociodemographic (sex, age, marital status) and professional (teaching-related variables such as education degree and teaching years) data were collected.

The Compassionate Engagement and Action Scales (CEAS; Gilbert et al., 2017; Portuguese version by Matos et al., 2015) were developed based on Gilbert’s evolutionary multidimensional model of compassion and the CFT framework and were designed to assess the three flows of compassion: (1) Self-compassion, (2) Compassion for Others, (3) Compassion from Others. Each of these flows entails (i) Compassionate Engagement (i.e. sensitivity to and motivation to engage with suffering) with items addressing competencies of sensitivity, empathy, sympathy, distress tolerance, non-judgment, and care for wellbeing and (ii) Compassionate Action (i.e. committed actions attempting to alleviate and prevent suffering), with items tapping the domains of helpful attending, thinking/reasoning, behaving, and emotion/feeling. Each scale’s instructions encompass a definition of compassion. The items are answered regarding the frequency of responding to one’s own suffering, others’ suffering, or the experience of accepting compassion from others, using a scale varying from never (1) to always (10). All subscales presented acceptable to high reliabilities (0.72 to 0.94) in the original study (Gilbert et al., 2017). In the current study, the Self-compassion subscale presented Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90, the Compassion for Others subscale of 0.90, and the Receiving Compassion from Others subscale of 0.96.

The Fears of Compassion Scale (FoC; Gilbert et al., 2011; Portuguese version by Matos et al., 2016) is a 38-item self-report instrument designed to measure fears, blocks, and resistances to compassion. Its items assess barriers to giving compassion to others (10 items), receiving compassion from others (13 items), and being self-compassionate (15 items). The items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from don’t agree at all (0) to completely agree (4). In its original study, Cronbach’s alpha values for the fears of giving compassion to others, receiving compassion from others, and being self-compassionate were 0.87, 0.88, and 0.89, respectively (Gilbert et al., 2011). Cronbach’s alphas for the three subscales found in the current study were as follows: 0.89 for Fear of Compassion for Self, 0.88 for Fear of Compassion from Others, and 0.87 for Fear of Compassion for Others.

The Shirom-Melamed Burnout Measure (SMBM; Armon et al., 2012; Portuguese version by Gomes, 2012) is a 14-item self-report instrument that assesses work-related burnout. A 7‐point scale, ranging from never (1) to always (7) is used to rate the items, with higher scores representing higher burnout symptoms. The SMBM encompasses three work-related dimensions: physical exhaustion, cognitive weariness, and emotional exhaustion. For this study, only the total SMBM score was used. Prior studies using the SMBM found excellent internal consistency (e.g. α = 0.96 for the total score; Baganha et al., 2016). In this study, the SMBM Cronbach’s alpha was 0.94.

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995; Portuguese version by Pais-Ribeiro et al., 2004) is a broadly used self-report instrument encompassing three subscales: (1) Depression (7 items), (2) Anxiety (7 items), and (3) Stress symptoms (7 items). The items are answered using a 4‐point scale ranging from did not apply to me at all (0) to applied to me very much, or most of the time (3), concerning the symptoms’ frequency during the previous week. In the original study, Cronbach’s alphas found for the three subscales were 0.94 for Depression symptoms, 0.87 for Anxiety symptoms, and 0.91 for Stress symptoms (Antony et al. 1998). In our sample, Cronbach’s alpha values were 0.88, 0.84, and 0.87 for Depression, Anxiety, and Stress symptoms, respectively.

The Types of Positive Affect Scale (TPAS; Gilbert et al., 2008; Portuguese version by Pinto-Gouveia et al., 2008) is an 18-item scale developed to measure the degree to which people experience different positive emotions in general. The TPAS targets three different types of positive affect, namely Active Positive Affect (e.g. energetic, excited, eager), Relaxed Positive Affect (e.g. calm, relaxed, serene), and Safe Positive Affect (e.g. safe, secure, content). Participants are asked to rate how typical each feeling is of them, using a 5-point scale ranging from not characteristic of me (0) to very characteristic of me (4). Gilbert et al. (2008) found Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83 for both the Relaxed and Active Positive Affect and 0.73 for Safe/Content Positive Affect. In the current study, the Active Positive Affect subscale revealed Cronbach’s alpha of 0.74, the Relaxed Positive Affect subscale of 0.84, and the Safe Positive Affect of 0.81.

The Emotional Climate in Organizations Scale (ECOS; Albuquerque et al., 2023) was designed based on Gilbert’s (2009) affect regulation systems model and measures the presence/activation of the threat, drive, and soothing-safeness systems at work (i.e. at school). It comprises three scales: (1) Emotions (15 items, 5 per each affect regulation system; e.g. Threat: anxious, irritated; Drive: lively, enthusiastic; Safe: connected, safe), (2) Satisfaction of Needs (15 items, five per each affect regulation system), and (3) Motives underlying one’s actions (15 items, five per each affect regulation system). The ECOS items are rated using a 5-point Likert type ranging from never (0) to always (4). In the current study, only the Emotions scale was used, assessing the activation of each of the threat, drive, and soothing-safeness affect regulation systems at work. Results from the ECOS preliminary psychometric characteristics study suggest that the scales are valid and reliable, showing the following Cronbach’s alpha values: α = 0.75 for the Threat Emotions scale, α = 0.86 for the Drive Emotions scale, and α = 0.83 for the Soothing-Safeness Emotions scale (Albuquerque et al., submitted manuscript). In the current sample, the Emotions scale showed Cronbach’ alpha values of 0.74, 0.84, and 0.81 for the Threat, Drive, and Soothing-Safeness scales, respectively.

Data Analyses

All data analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 27. The listwise deletion method was used to address the missing data. The correlations between all variables at baseline are presented in a Supplemental table (SI 2). To explore whether changes in the three flows of compassion and fears of self-compassion, and safe, drive, and threat emotions mediated the impact of the CMT-T intervention on changes in participant’s depression, anxiety, stress, and burnout symptoms, and positive affect at post-intervention, MEMORE 2.1 (Mediation and Moderation analysis for Repeated measures designs) was used (Montoya & Hayes, 2017). MEMORE is a macro for SPSS that enables the estimation of total, direct, and indirect effects of independent variable (X) on dependent variable (Y) through one or more mediators (M), concurrently or in sequence in two-condition or two-occasion within-subjects design. MEMORE’s approach was specifically selected since it defines mediation analysis using a path analytic framework instead of a set of discrete hypothesis tests. This decreases the number of tests required to test indirect effects, diminishing the chances of inferential errors. MEMORE calculates the difference between the two mediator measurements and the difference between the two dependent variable measurements (Montoya & Hayes, 2017). In the present study, all participants completed the CMT-T intervention, and the hypothesized mediators and main outcomes were assessed at baseline and post-intervention. Thus, the independent variable “X” represents the passage of time that corresponds to the intervention period (i.e. CMT-T intervention). Figure 2 depicts the conceptual model of the between-subjects mediation analysis. Additionally, MEMORE produces 95% confidence intervals for indirect effect(s) using bootstrapping resampling method. Statistical significance of the effect is considered (p < 0.050) if zero is not included within the interval between the lower and the upper bound of the confidence interval (Montoya & Hayes, 2017).

Lastly, two serial mediation models were conducted to test if changes from baseline to post-intervention on teacher’s burnout levels were mediated by changes occurring in fears of self-compassion (Model 1), fears of compassion from others (Model 2), and stress (Model 1 and Model 2).

Results

To explore the mechanisms of change on CMT-T main outcomes, two-condition within-subject mediation analyses were performed using MEMORE. Changes from baseline to post-treatment in the three flows of compassion and fears of self-compassion, and safe, drive, and threat emotions were hypothesized as possible mediators of changes in depression, anxiety, stress, and burnout symptoms and positive affect. Changes in all outcomes were assessed from baseline to post-treatment. Tables 1 and 2 display the results found for the indirect effects of the intervention on changes in all outcome variables through the hypothesized mediators. Given that we aimed to explore the unique and specific contribution of each mediator process, all analyses were conducted separately.

Concerning burnout, results showed that all flows of compassion and fear of compassion from others mediated the changes from baseline to post-intervention (Table 1). Results showed that participants presented less burnout symptoms at post-intervention, relative to baseline, through the development of compassion skills (directed at oneself, at others, and received from others). Furthermore, another indirect effect on participants’ burnout levels occurred through the intervention’s effect on decreasing fear of compassion from others, from baseline to post CMT-T intervention.

In addition, results showed that all flows of compassion and fears of compassion (for self and from others) acted as significant mediators of the impact of the intervention on changes in teachers’ anxiety and stress levels from baseline to post-intervention, except for compassion to others that was not a significant mediator for the changes found in stress levels (Table 1). Thus, teachers’ decrease in anxiety and stress levels were, at least partially, explained through the increase of their compassion skills and decrease in fears of compassion for self and in receiving compassion from others.

As for depressive symptoms, only fears of compassion from others and drive emotions at work presented a mediator effect of the intervention (Table 1). Thus, the reductions observed in teachers’ depressive symptoms from baseline to post-intervention were partially explained by decreases in their fears of compassion from others and increases in the activation of their drive system.

Concerning positive affect outcomes (Table 2), results showed that all three flows of compassion were significant mediators of the increase found in teacher positive affect after the intervention. Specifically, the increase in active and safe positive affect found after the intervention occurred through the effect of the intervention in increasing the three compassion flows. Moreover, changes in active positive affect were also due to an increased activation of teacher drive system emotions at work. Finally, concerning changes in relaxed positive affect results indicated that these were mediated by an increase in the activation of soothing-safeness system emotions at work, as well as in self-compassion and compassion from others, that occurred from baseline to post-intervention.

We explored whether the impact of the intervention on participants’ burnout levels from baseline to post-intervention would be mediated by the decrease in fears of self-compassion (Model 1) and fears of compassion from others (Model 2) and if these changes were mediated by decreased stress symptoms, through two serial mediation models. For Model 1 (Fig. 3), three indirect effects were explored: (1) “X: CMT-T intervention” → Fears of Self-compassion → Burnout (B = 0.184, BootSE = 0.748, 95% CI [− 1.055 to 1.942]); (2) “X: CMT-T intervention” → Stress → Burnout (B = 0.306, BootSE = 0.486, 95% CI [− 0.574 to 1.328]); and (3) “X: CMT-T intervention” → Fears of Self-compassion → Stress → Burnout (B = 0.380 BootSE = 0.261, 95% CI [− 0.005 to 1.023]), as well as a total indirect effect (B = 0.870, SE = 0.935, 95% CI [− 0.632 to 3.004]). Additionally, the total effect (including direct and indirect effects) (t(101) = − 3.197, p = 0.002; B = − 4.324, SE = 1.352, 95% CI [1.641 to 7.006]) and the direct effect of “X: CMT-T intervention” on Burnout were significant (t(97) = 2.398, p = 0.018; B = 3.453, SE = 1.440, 95% CI [0.595 to 6.311]). The model was significant (F(4,97) = 2.448, p = 0.050) and accounted for 9.2% of changes in Burnout from baseline to post-intervention.

The same paths were explored for Model 2 (Fig. 4), including three indirect effects: (1) “X: CMT-T intervention” → Fears of Compassion from Others → Burnout (B = 0.706, BootSE = 0.573, 95% CI [− 0.143 to 2.099]); (2) “X: CMT-T intervention” → Stress → Burnout (B = 0.292, BootSE = 0.427, 95% CI [− 0.481 to 1.267]); and (3) “X: CMT-T intervention” → Fears of Compassion from Others → Stress → Burnout (B = 0.325, BootSE = 0.215, 95% CI [0.029 to 0.852]), as well as a total indirect effect (B = 1.324, SE = 0.765, 95% CI [0.124 to 3.138]). In addition, the total effect (including direct and indirect effects) (t(101) = 3.197, p = 0.002; B = − 4.324, SE = 1.352, 95% CI [1.641 to 7.006]) and the direct effect of “X: CMT-T intervention” on Burnout were significant (t(97) = 2.216, p = 0.029; B = 3.000, SE = 1.354, 95% CI [0.313 to 5.686]). The model was significant (F(4,97) = 4.362, p = 0.010) and accounted for 15.2% of changes in Burnout from pre-to-post-intervention.

Discussion

Recently, CMT-T revealed promising results in reducing teachers’ depressive, anxiety, stress, and burnout symptoms (Matos et al., 2022a, b). Nevertheless, gathering knowledge concerning the mechanisms of change found in the intervention’s main outcomes is of paramount importance to make interventions more effective, yet these are usually less explored (McCracken & Gutiérrez-Martínez, 2011). Thus, the primary objective of the current study was to understand whether changes in compassion, fears of compassion, and safe, drive, and threat emotions mediated the impact of the CMT-T intervention on changes in teacher’s psychopathological symptoms and positive affect at post-intervention.

Overall, concerning psychopathological outcomes, the three flows of compassion as well as fears of compassion from others were particularly relevant as they mediated changes in participants’ depressive, anxiety, stress, and burnout symptoms. More specifically, compassion (for self, for others, and from others) and fears of compassion from others were all significant mediators of the reductions found in teachers’ burnout and anxiety symptoms (fears of self-compassion only mediated changes in anxiety). Concerning stress, an identical pattern of results was found with compassion for self, fears of self-compassion, and fears of compassion from others being the significant mediators for the changes found. These results support the CFT/CMT theoretical framework (Gilbert, 2014, 2020) highlighting the importance of developing one’s compassionate motivational systems through the cultivation of the three compassion flows, while also targeting the inhibitors of compassion (fears), as two key mechanisms through which CMT operates to decrease psychological distress in teachers. Specifically, developing teachers’ competencies to be sensitive to their own and others’ difficulties and distress, and fostering their commitment and ability to proficiently deal with these difficulties in an attempt to prevent and alleviate their psychological distress. Simultaneously, weakening teachers’ fears and resistances of receiving compassion from oneself and others, and of directing compassion to others, may act as a mechanism to diminish their depressive, anxiety, stress, and burnout symptoms. These findings are in line with previous work documenting that improvements in the flows of compassion and fears of compassion were associated with positive changes in psychopathological symptoms as a result of CFT/CMT interventions (e.g. Braehler et al., 2013; Matos et al., 2022c; Sommers-Spijkerman et al., 2018).

Interestingly, only decreases in fears of compassion from others and increases in drive emotions at work mediated changes in teachers’ depressive symptoms. Adding to prior studies examining CFT/CMT mechanisms of change (e.g. Matos et al., 2022a, c; Sommers-Spijkerman et al., 2018), these findings suggest the importance of working with people’s blocks and resistances of receiving compassion, as well as stimulating the activation of drive system related emotions (excitement and pleasure) to promote an improvement in negative mood and depressive symptomatology. This may allow individuals to be more open to receive compassion from others and thus reduce feelings of isolation, as well as promote engagement in activities that activate the drive system, which in turn increases energy levels and positive affect.

Another relevant finding was the fact that the development of compassion abilities (for self, for others and from others) stood out as key mediators of change of CMT-T in positive affect. It seems that promoting a more understanding, caring, and compassionate stand towards themselves and others was crucial to increase teachers’ positive affect, namely feelings of safeness, relaxation, and activation. In addition, and according to the CFT model, the activation of the drive system in the workplace (i.e. increases in drive emotions at school) mediated changes in active positive affect, that is, feelings of vitality, enthusiasm, and energy, which are related to the overall activation of the drive system. In turn, the activation of the soothing-safeness system in the workplace (i.e. increases in soothing-safeness emotions at school) mediated an increase in relaxed positive affect, that is feelings of calm, peacefulness, and relaxation, linked to the activation of the soothing-safeness system, as well as to an overall deactivation of the threat system. Unexpectedly, increases in teachers’ soothing emotions at work did not mediate increases in overall safe positive affect. A tentative explanation for this finding might be that increasing teachers’ experiences of feeling safe and relaxed at work during the CMT-T is not enough to improve overall feelings of safeness, contentment, and connectedness to others, which seem to change more as a result of increases in compassionate competencies and motives towards the self and others. As a whole, these findings corroborate the CFT theoretical model by revealing that CMT seems to stimulate and promote affiliative care-focused emotions and motivational systems and support the down-regulation of threat-focused systems, leading to improvements in wellbeing (Gilbert, 2010, 2014, 2020). Furthermore, these results address limitations of previous research, by examining changes in the three-affect regulation systems in the context where CMT is applied as potential mechanisms of change underlying the effectiveness of this intervention on positive affect.

Finally, the two serial mediational models tested revealed that, although the CMT-T intervention had a direct impact on the decrease in teachers’ burnout symptoms at post-intervention, this effect was partially mediated by the impact of the intervention on stress levels, which in part was due to reducing fears of compassion (for self and from others). The model accounted for 9.2% and 15.2% of changes in participants’ burnout, which can be interpreted as small to moderate proportion of the burnout variance explained by the model (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). These findings extend prior research on mechanisms of change in CFT/CMT (e.g. Braehler et al., 2013; Matos et al., 2022c; Sommers-Spijkerman et al., 2018), revealing that reductions in emotional, cognitive, and physical burnout symptoms in teachers following the CMT-T are partly explained by the fact that this intervention contributes to mitigate the fears, blocks, and resistances of being compassionate towards oneself and receiving compassion from others, which in turn lead to the down-regulation of the threat system and related decrease in stress symptoms.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although the current findings add to previous literature and may inform the future development of interventions and research, there are a few limitations that should be acknowledged. One limitation pertains to the temporal ordering of mediator and outcome variables, which is relevant to define causal mediation (Kazdin, 2009), and in this study the assessment of the changes in mediator and outcome variables was conducted at the same time point. In order to determine whether changes in compassion and fears of compassion across the intervention lead to changes in psychopathology and positive affect at post-intervention, future studies should seek to measure mediators and outcomes at different time points throughout the CMT-T intervention. Another limitation of the present study is the potential risk for demand characteristics on participants given that self-report questionnaires were used to assess the constructs that were directly addressed by the CMT-T intervention. Moreover, the generalizability of the findings to broader educational contexts may be limited by the particular characteristics of the study sample (e.g. public school teachers, unequal gender distribution with overrepresentation of female teachers, teachers from the same region of the country). Therefore, future research should aim to confirm these results in more representative samples of teachers with equal gender and diverse regional representation. In addition, considering that previous studies have pointed to the role that practice frequency, perception of practice helpfulness, and the embodiment of the compassionate self play in fostering changes in a CMT intervention (Maratos et al., 2019; Matos et al., 2018), future studies could examine the effect of these practice indicators on changes occurring after the CMT-T. Furthermore, the listwise deletion method used to address the missing data can also introduce some bias, for example by reducing the sample size or external validity. In the future, other approaches such as multiple imputation could be implemented.

Despite the abovementioned limitations, findings from the present study provide an insightful contribution to the field of compassion-focused interventions and add to the empirical support of the theoretical foundations of CFT/CMT. Taken together, our results highlight that the psychoeducation contents and body-based and compassion imagery practices of the CMT-T intervention seem to effectively foster the cultivation of teachers’ compassion motives and competencies directed towards oneself and others and attenuate their fears, blocks, and resistances to the experience of compassion for oneself and for others, and of receiving compassion from others, as well as promote the activation of the soothing-safeness system and of the drive system in the workplace. These beneficial effects, in turn, seem to contribute to improvements in teachers’ psychopathological symptoms and overall positive affect in the aftermath of the CMT-T. In line with the CFT theoretical framework (Gilbert, 2010, 2014, 2020), these findings highlight that to cultivate and embody a compassionate self/mind, reduce psychological distress and burnout, and promote wellbeing in educational settings it is crucial to simultaneously promote teachers’ compassionate mind competencies and skills, address the existent barriers and inhibitors to compassion, strengthen their soothing-safeness regulation system (e.g. emotions of contentment, peacefulness, relaxation), and facilitate access to the drive system (e.g. emotions of vitality, enthusiasm, energy) in schools.

To sum, the current study’s overall findings demonstrate the value and significance of implementing compassion-focused interventions in educational contexts, as a mean to promote the cultivation of socio-emotional competencies and compassion motives in teachers, which could positively impact their mental health and wellbeing. In addition, applying interventions like the CMT-T may contribute to foster a compassionate, prosocial, and resilient culture in school settings, addressing important international recommendations for sustainable development that place a high priority on fostering peaceful, resilient, and inclusive societies; promoting health and wellbeing; and assuring equitable quality education for all (United Nations, 2015).

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the authors.

References

Agyapong, B., Obuobi-Donkor, G., Burback, L., & Wei, Y. (2022). Stress, burnout, anxiety and depression among teachers: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10706. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710706

Albuquerque, I., Matos, M., Galhardo, A., Cunha, M., Palmeira, L., Lima, M., Gilbert, P., & Irons, C. (2023). The Emotional Climate in Organizations Scales: Psychometric properties and factor structure. [Manuscript in preparation]. CINEICC, University of Coimbra.

Antony, M. M., Bieling, P. J., Cox, B. J., Enns, M. W., & Swinson, R. P. (1998). Psychometric properties of the 42- item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychological Assessment, 10(2), 176–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.10.2.176

Armon, G., Shirom, A., & Melamed, S. (2012). The big five personality factors as predictors of changes across time in burnout and its facets. Journal of Personality, 80(2), 403–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2011.00731.x

Baganha, C., Gomes, A.R., & Esteves, A. (2016). Stresse ocupacional, avaliação cognitiva, burnout e comprometimento laboral na aviação civil. Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças, 17(2), 164–179. https://doi.org/10.15309/16psd170212

Beaumont, E., & Martin, C. J. H. (2016). Heightening levels of compassion towards self and others through use of compassionate mind training. British Journal of Midwifery, 24(11), 777–786. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjom.2016.24.11.777

Beaumont, E., Irons, C., Rayner, G., & Dagnall, N. (2016). Does compassion-focused therapy training for health care educators and providers increase self-compassion and reduce self-persecution and self-criticism? Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 36(1), 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEH.0000000000000023

Beaumont, E. A., Bell, T., McAndrew, S. L., & Fairhurst, H. L. (2021). The impact of Compassionate Mind Training on qualified health professionals undertaking a compassion focused therapy module. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 21(4), 910–922. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12396

Braehler, C., Gumley, A., Harper, J., Wallace, S., Norrie, J., & Gilbert, P. (2013). Exploring change processes in compassion focused therapy in psychosis: Results of a feasibility randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 52(2), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12009

Craig, C., Hiskey, S., & Spector, A. (2020). Compassion focused therapy: A systematic review of its effectiveness and acceptability in clinical populations. Expert Review Neurotherapeutics, 20(4), 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737175.2020.1746184

de Matos, M. G., Branquinho, C., Noronha, C., Moraes, B., Gaspar, T., & Rodrigues N. N. (2023). Observatory of psychological health and well-being: Monitoring and action in Portuguese schools. Revista Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças, 24(3), 843–854. https://doi.org/10.15309/23psd240305

Education Support Partnership. (2018). Teacher well-being index 2018. https://www.educationsupportpartnership.org.uk/sites/default/files/resources/teacher_wellbeing_index_2018.pdf. Accessed 05.03.2020.

Gilbert, P. (2014). The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53(1), 6–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12043

Gilbert, P. (2020). Compassion: From its evolution to a psychotherapy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 586161. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.586161

Gilbert, P., & Mascaro, J. (2017). Compassion fears, blocks, and resistances: An evolutionary investigation. In E. M. Seppälä, E. Simon-Thomas, S. L. Brown, M. C. Worline, L. Cameron, & J. R. Doty (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of compassion science (pp. 399–420). Oxford University Press.

Gilbert, P., & Procter, S. (2006). Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism: Overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy: An International Journal of Theory & Practice, 13(6), 353–379. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.507

Gilbert, P., McEwan, K., Mitra, R., Franks, L., Richter, A., & Rockliff, H. (2008). Feeling safe and content: A specific affect regulation system? Relationship to depression, anxiety, stress, and self-criticism. Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(3), 182–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760801999461

Gilbert, P., McEwan, K., Matos, M., & Rivis, A. (2011). Fears of compassion: Development of three self-report measures. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 84, 239–255. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608310X526511

Gilbert, P., Catarino, F., Duarte, C., Matos, M., Kolts, R., Stubbs, J., Ceresatto, L., Duarte, J., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Basran, J. (2017). The development of Compassionate Engagement and Action Scales for self and others. Journal of Compassionate Health Care, 4(4), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40639-017-0033-3

Gilbert, P., Matos, M., Wood, W., & Maratos, F. (2020). The compassionate mind and the conflicts between competing and caring: Implications for educating young minds. In M. I. Coles & B. Gent (Eds.), Education for survival: The pedagogy of compassion (pp. 44–76). Trentham Books.

Gilbert, P., & Choden, K. (2013). Mindful compassion. Constable-Robinson Ltd.

Gilbert, P. (2009). The compassionate mind: A new approach to facing the challenges of life. Constable Robinson Ltd.

Gilbert, P. (2010). Compassion focused therapy: Distinctive features. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203851197

Gilbert, P. (2017). Compassion: Definitions and controversies. In P. Gilbert (Ed.), Compassion: Concepts, research and applications (pp. 3–15). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315564296-1

Gomes, A. R. (2012). Medida de “Burnout” de Shirom-Melamed (MBSM). Unpublished technical report.

Gray, C., Wilcox, G., & Nordstokke, D. (2017). Teacher mental health, school climate, inclusive education and student learning: A review. Canadian Psychology, 58(3), 203–210. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000117

Hanh, T. N., & Weare, K. (2017). Happy teachers change the world. Parallax Press.

Harding, S., Morris, R., Gunnell, D., Ford, T., Hollingworth, W., Tilling, K., Evans, R., Bell, S., Grey, J., Brockman, R., Campbell, R., Araya, R., Murphy, S., & Kidger, J. (2019). Is teachers’ mental health and wellbeing associated with students’ mental health and wellbeing? Journal of Affective Disorders, 253, 460–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.080

Hemming, K., Haines, T. P., Chilton, P. J., Girling, A. J., & Lilford, R. J. (2015). The stepped wedge cluster randomised trial: Rationale, design, analysis, and reporting. BMJ, 350, h391. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h391

Hoglund, W. L. G., Klingle, K. E., & Hosan, N. E. (2015). Classroom risks and resources: Teacher burnout, classroom quality and children’s adjustment in high needs elementary schools. Journal of School Psychology, 53(5), 337–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2015.06.002

Hwang, Y. S., Bartlett, B., Greben, M., & Hand, K. (2017). A systematic review of mindfulness interventions for in-service teachers: A tool to enhance teacher wellbeing and performance. Teaching and Teacher Education, 64, 26–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.01.015

Irons, C., & Beaumont, E. (2018). The compassionate mind workbook: A step-by-step guide to developing your compassionate self. Robinson.

Irons, C., & Heriot-Maitland, C. (2020). Compassionate Mind Training: An 8-week group for the general public. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 94(3), 443–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12320

Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 491–525. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308325693

Jennings, P. A., DeMauro, A. A., & Mischenko, P. P. (Eds.). (2019). The mindful school: Transforming school culture through mindfulness and compassion. Guilford Publications.

Katz, D. A., Greenberg, M. T., Klein, L. C., & Jennings, P. A. (2016). Associations between salivary α-amylase, cortisol and self-report indicators of health and well-being among educators. Teacher and Teacher Education, 54, 98–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.11.012

Kazdin, A. E. (2009). Understanding how and why psychotherapy leads to change. Psychotherapy Research, 19(4–5), 418–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300802448899

Kim, J. J., Parker, S. L., Doty, J. R., Cunnington, R., Gilbert, P., & Kirby, J. N. (2020). Neurophysiological and behavioural markers of compassion. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 6789. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-63846-3

Kirby, J., & Gilbert, P. (2017). The emergence of the compassion focused therapies. In P. Gilbert (Ed.), Compassion: Concepts, research and applications (pp. 258–285). Routledge.

Kirby, J. N., Doty, J. R., Petrocchi, N., & Gilbert, P. (2017a). The current and future role of heart rate variability for assessing and training compassion. Frontiers in Public Health, 5, 40. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00040

Kirby, J. N., Tellegen, C. L., & Steindl, S. R. (2017b). A meta-analysis of compassion-based interventions: Current state of knowledge and future directions. Behavior Therapy, 48, 778–792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2017.06.003

Kirby, J. N., Day, J., & Sagar, V. (2019). The ‘Flow’ of compassion: A meta-analysis of the fears of compassion scales and psychological functioning. Clinical Psychology Review, 70, 26–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2019.03.001

Lavelle, B. D. (2017). Compassion in context: Tracing the Buddhist roots of secular, compassion-based contemplative programs. In E. M. Seppälä, E. Simon-Thomas, S. L. Brown, M. C. Worline, C. D. Cameron, & J. R. Doty (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of compassion science (pp. 17–26). Oxford University Press.

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

Maratos, F. A., Montague, J., Ashra, H., Welford, M., Wood, W., Barnes, C., Sheffield, D., & Gilbert, P. (2019). Evaluation of a Compassionate Mind Training intervention with school teachers and support staff. Mindfulness, 10(11), 2245–2258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01185-9

Maratos, F., Matos, M., Albuquerque, I., Wood, W., Palmeira, L., Cunha, M., Lima, M. P., & Gilbert, P. (2020). Exploring the international utility of progressing Compassionate Mind Training in school settings: A comparison of implementation effectiveness of the same curricula in the UK and Portugal. Psychology of Education Review, 44(2), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsper.2020.44.2.73

Maratos, F. A., Wood, W., Cahill, R., Hernández, Y., Matos, M., & Gilbert, P. (2024). A mixed-methods study of Compassionate Mind Training for Pupils (CMT-Pupils) as a school-based wellbeing intervention. Mindfulness, 15(2), 459–478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-024-02303-y

Maratos, F. A., Hurst, J., Harvey, C., & Gilbert, P. (2022). Embedding compassion in schools: The what's, the why's, and the how's. In A. Giraldez-Hayes, & J. Burke (Eds.), Applied positive school psychology (pp. 81–100). Routledge.

Matos, M., Pinto-Gouveia, J., Duarte, C., & Duarte, J. (2015). Compassionate Engagement and Action Scales for self and others. [Portuguese translation] Unpublished manuscript.

Matos, M., Pinto-Gouveia, J., Duarte, J., & Simões, D. (2016). The fears of compassion scales. [Portuguese translation] Unpublished manuscript.

Matos, M., Duarte, C., Duarte, J., Pinto-Gouveia, J., Petrocchi, N., Basran, J., & Gilbert, P. (2017). Psychological and physiological effects of compassionate mind training: A pilot randomised controlled study. Mindfulness, 8(6), 1699–1712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0745-7

Matos, M., Duarte, C., Duarte, J., Gilbert, P., & Pinto-Gouveia, J. (2018). How one experiences and embodies compassionate mind training influences its effectiveness. Mindfulness, 9(4), 1224–1235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0864-1

Matos, M., Albuquerque, I., Galhardo, A., Cunha, M., Lima, M. P., Palmeira, L., Petrocchi, N., McEwan, K., Maratos, F., & Gilbert, P. (2022a). Nurturing compassion in schools: A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of a Compassionate Mind Training program for teachers. PLoS ONE, 17(3), e0263480. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263480

Matos, M., Duarte, C., Duarte, J., Pinto-Gouveia, J., Petrocchi, N., & Gilbert, P. (2022b). Cultivating the compassionate self: An exploration of the mechanisms of change in compassionate mind training. Mindfulness, 13(1), 66–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-021-01717-2

Matos, M., Palmeira, L., Albuquerque, I., Cunha, M., Lima, M. P., Galhardo, A., Maratos, F., & Gilbert, P. (2022c). Building compassionate schools: Pilot study of a Compassionate Mind Training intervention to promote teachers’ well-being. Mindfulness, 13(1), 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-021-01778-3

McCallum, F., Price, D., Graham, A., & Morrison, A. (2017). Teacher well-being: A review of the literature. The Association of Independent Schools of New South Wales Limited. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2017-10/apo-nid201816.pdf

McCracken, L. M., & Gutiérrez-Martínez, O. (2011). Processes of change in psychological flexibility in an interdisciplinary group-based treatment for chronic pain based on acceptance and commitment therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(4), 267–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.02.004

McEwan, K., Minou, L., Moore, H., & Gilbert, P. (2020). Engaging with distress: Training in the compassionate approach. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 27(6), 718–727. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12630

McLean, L., & Connor, C. M. (2015). Depressive symptoms in third-grade teachers: Relations to classroom quality and student achievement. Child Development, 86(3), 945–954. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12344

Montoya, A. K., & Hayes, A. F. (2017). Two condition within-participant statistical mediation analysis: A path-analytic framework. Psychological Methods, 22(1), 6–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000086

Murphy, R., Cooper, Z., Hollon, S. D., & Fairburn, C. G. (2009). How do psychological treatments work? Investigating mediators of change. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.10.001

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development – OECD. (2021). Positive, high-achieving students?: What schools and teachers can do. https://doi.org/10.1787/3b9551db-en

Pais-Ribeiro, J. L., Honrado, A., & Leal, I. (2004). Contribuição para o estudo da adaptação portuguesa das escalas de ansiedade, depressão e stress (EADS) de 21 itens de Lovibond e Lovibond. Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças, 5(2), 229–239.

Pinto-Gouveia, J., Dinis, A., & Matos, M. (2008). Types of Positive Affect Scale. [Portuguese translation] Unpublished manuscript.CINEICC, University of Coimbra.

Porges, S. W. (2007). The polyvagal perspective. Biological Psychology, 74(2), 116–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.06.009

Redín, C. I., & Erro-Garcés, A. (2020). Stress in teaching professionals across Europe. International Journal of Educational Research, 103, 101623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101623

Roeser, R. W., Collaianne, B. A., & Greenberg, M. A. (2018). Compassion and human development: Current approaches and future directions. Research in Human Development, 15(3–4), 238–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2018.1495002

Seppälä, E. M., Simon-Thomas, S., Brown, S. L., Worline, M. C., Cameron, C. D., & Doty, J. R. (2017). The Oxford handbook of compassion science. Oxford University Press.

Singer, T., & Engert, V. (2019). It matters what you practice: Differential training effects on subjective experience, behavior, brain and body in the ReSource Project. Current Opinion in Psychology, 28, 151–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.12.005

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2015). Job satisfaction, stress and coping strategies in the teaching profession-What do teachers say? International Education Studies, 8(3), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v8n3p181

Sommers-Spijkerman, M., Trompetter, H., Schreurs, K., & Bohlmeijer, E. (2018). Pathways to improving mental health in compassion-focused therapy: Self-reassurance, self-criticism and affect as mediators of change. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2442. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02442

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Pearson/Allyn & Bacon.

United Nations General Assembly. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Retrieved from https://www.refworld.org/legal/resolution/unga/2015/en/111816

Varela, R. C., della Santa, R., Silveira, H., Coimbra de Matos, A., Rolo, D., Areosa, J., & Leher, R. (2018). Inquérito nacional sobre as condições de vida e trabalho na educação em Portugal (INCVTE). Jornal da FENPROF. https://www.fenprof.pt/?aba=39&cat=667

Welford, M., & Langmead, K. (2015). Compassion-based initiatives in educational settings. Educational and Child Psychology, 32(1), 71–80. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsecp.2015.32.1.71

Zarate, K., Maggin, D. M., & Passmore, A. (2019). Meta-analysis of mindfulness training on teacher well-being. Psychology in the Schools, 56(10), 1700–1715. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22308

Acknowledgements

We are greatly indebted to the grant and support from Sarah and John Rockliff and the Reed foundation, and to the Compassionate Mind Foundation. The authors would also like to thank the educational institutions that collaborated with this project and the teachers for their kind participation.

Funding

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on). This work has been funded by the Reed Foundation (UK) and supported by the Compassionate Mind Foundation (UK).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Marcela Matos, Ana Galhardo, Lara Palmeira, Isabel Albuquerque, Marina Cunha, Margarida Pedroso Lima, Paul Gilbert; methodology: Marcela Matos, Ana Galhardo, Lara Palmeira, Isabel Albuquerque, Marina Cunha, Margarida Pedroso Lima; formal analysis and investigation: Marcela Matos, Lara Palmeira, Ana Galhardo; writing — original draft preparation: Marcela Matos, Ana Galhardo, Lara Palmeira, Marina Cunha; writing — review and editing: Marcela Matos, Ana Galhardo, Lara Palmeira, Marina Cunha, Margarida Pedroso Lima, Frances Maratos, Paul Gilbert; funding acquisition: Marcela Matos, Frances Maratos, Paul Gilbert; resources: Marcela Matos, Isabel Albuquerque, Frances Maratos, Paul Gilbert; supervision: Marcela Matos, Frances Maratos, Paul Gilbert.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval Statement

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of the University of Coimbra (CEDI22.03.2018) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier, NCT05107323).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Informed consent clarified the voluntary, confidential, and anonymous nature of the study and data protection rights.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

No AI tools were used for the purpose of this study and paper preparation.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Matos, M., Galhardo, A., Palmeira, L. et al. Promoting Teachers’ Wellbeing Using a Compassionate Mind Training Intervention: Exploring Mechanisms of Change. Mindfulness (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-024-02360-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-024-02360-3