Abstract

Teachers’ belief systems about the inclusion of students with special needs may explain gaps between policy and practice. We investigated three inter-related aspects of teachers’ belief systems: teachers’ cognitive appraisals (e.g., attitudes), emotional appraisal (e.g., feelings), and self-efficacy (e.g., agency to teach inclusive classrooms). To date, research in this field has produced contradictory findings, resulting in a sparse understanding of why teachers differ in their belief systems about inclusive education, and how teachers’ training experiences contribute to their development of professional beliefs. We used meta-analysis to describe the level and range of teachers’ beliefs about inclusive education, and examine factors that contribute to variation in teachers’ beliefs, namely (1) the point in teachers’ career (pre-service versus in-service), (2) training in special versus regular education, and (3) the effects of specific programs and interventions. We reviewed 102 papers (2000–2020) resulting in 191 effect sizes based on research with 40,898 teachers in 40 countries. On average, teachers’ cognitive appraisals, emotional appraisals, and efficacy about inclusion were found to be in the mid-range of scales, indicating room for growth. Self-efficacy beliefs were higher for preservice (M = 3.69) than for in-service teachers (M = 3.13). Teachers with special education training held more positive views about inclusion than regular education teachers (d = 0.41). Training and interventions related to improved cognitive appraisal (d = 0.63), emotional appraisal (d = 0.63), and self-efficacy toward inclusive practices (d = 0.93). The training was particularly effective in encouraging reflection of beliefs and, eventually, facilitating belief change when teachers gained practical experience in inclusive classrooms. Six key findings direct the next steps.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Teachers’ classroom practices and how they implement educational reform account substantially for students’ academic learning and achievement (Hattie, 2009). The United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD; 2006) and the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015 (United Nations, 2006) paved the way for reform toward inclusive education, and teachers play a key role in translating this reform into practice (Rouse, 2017). To implement the change towards more inclusive school systems, we must understand why some teachers use new teaching strategies while others resist inclusive reform efforts (Sutton & Wheatley, 2003). Identifying contributors and barriers to the implementation of inclusive education is a timely topic because inclusive education of students with special educational needs (SEN) has become one of the most significant educational reforms in countries all over the world (Savolainen et al., 2020).

A major driver for the development of inclusive education policies has been the right of children with SEN to be educated in mainstream schools. Yet, the likelihood of inclusive education actually occurring depends on teachers’ underlying belief systems (Lindsay, 2007). “Teachers’ belief systems” (Fives & Buehl, 2012, p. 477) refer to a set of dynamic and integrated teacher views related to a certain topic that guides their perceptions, leads them to interpret incoming information and events in certain ways, and acts as an individual’s “working model of the world” (Bandura, 1977, p. 3). The subcomponents of a teacher’s belief system are often entangled (e.g., Miesera et al., 2019; Woodcock & Jones, 2020). Knowing about teachers’ belief systems gives insights into the psychological experiences that drive teachers’ actions. Such knowledge is critical to inform teacher training (e.g., teacher preparation, professional development) that supports teachers’ implementation of reforms such as inclusive education. Using studies from across the globe and including high-, middle-, and low-income countries increases the likelihood that findings can be generalized widely.

There are numerous ways to build knowledge related to inclusive education. In this paper, we use studies from 40 countries to focus on teachers’ beliefs about inclusion as the key outcome. Yet, it seems important to acknowledge that research on teachers’ beliefs about inclusive education differs from research examining the effectiveness of inclusive education compared to other educational approaches. The latter is beyond the scope of this paper.

Researchers in education have produced a large body of work on teachers’ belief systems related to inclusive education. However, the existing research findings are contradictory and not easy to interpret. Some contradictions occur because of the wide range of beliefs teachers hold about inclusive education. Other contradictions reflect the variety of constructs studied; for instance, some work focuses on teaching approaches to inclusive education, other work focuses on thoughts about inclusive education, and still others assess teachers’ fears toward inclusive education. Given the existing contradictory information, the field needs a synthesis of research. We expect the resulting knowledge will shed light on factors that contribute to beliefs about inclusive education and inform teacher training in ways that will lead to inclusive education reform. For this reason, we conducted a meta-analysis to explain how and why teachers’ beliefs about inclusive education vary.

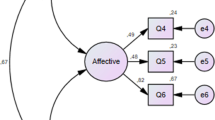

The goal of this article is twofold. To shed light on the variation of teachers’ beliefs about inclusive education, we investigate teachers’ belief systems regarding inclusive education and the extent to which they vary as a function of point in a career (i.e., preservice versus in-service) and teacher type (e.g., special education versus regular education). Then, we broaden the lens to understand how training and interventions provide teachers with experiences that contribute to teachers’ beliefs, such that teachers are more likely to implement inclusive practices (Forlin et al., 2014). To pursue these goals, first, we examine the effects of preservice teachers’ education and in-service teachers’ professional development on teachers’ beliefs on inclusive education. Second, we examine whether being a special or regular education teacher is related to teachers’ beliefs about inclusion. Third, to advance our knowledge about the malleability of inclusion-related beliefs, we examine the extent to which interventions (such as preservice courses, professional development training, and practical experiences in inclusive classrooms) moderate the effects of teacher education. We organize the literature by distinguishing between three components of beliefs—teachers’ cognitive appraisals (e.g., thoughts), emotional appraisals (e.g., feelings), and self-efficacy (e.g., agency to teach inclusive classrooms). The results provide the theoretical ground for future research on teachers’ belief systems about inclusive education reform, shed light on how teachers’ point in their career and whether they are special education versus regular teachers shape their belief systems about inclusive education reform, and provide information about what aspects of training and interventions are associated with more positive beliefs toward inclusion.

In the following section, we first describe the evidence for the implementation of the inclusive education reform and the role of teachers' beliefs in the implementation of this reform. Based on Gregoire's (2003) cognitive-affective model, we review the state of current research on teachers' belief systems and then describe factors that contribute to the development of teachers’ belief systems. Finally, we present our study and the research questions.

The Implementation and Effects of Inclusive Education

By definition, inclusive education refers to the education of all children within one classroom, irrespective of their cognitive or physiological conditions (UNESCO, 1994). Access to inclusive education has been viewed as a fundamental right of children with SEN and exclusion from such educational settings has been viewed as discrimination (Lindsay, 2007). The move toward inclusion is almost universal, and it reflects a change in values in many societies. However, there is remarkable variation in the definition and implementation of inclusive education around the world. According to UNESCO (2017a), most countries have committed to the United Nations’ Convention on CRPD; however, countries still differ substantially in terms of experience with inclusive education and the way in which inclusion is realized (O'Hanlon, 2017; UNESCO, 2017b). Hence, implementing inclusive education remains a work in progress (Westwood, 2018). Whereas some countries, such as the USA, have been changing their educational systems to integrate students with SEN into regular education classrooms for decades, most countries worldwide are currently in the process of aligning their educational systems with the United Nations’ Convention on CRPD.

Inclusion has become a goal in many nations, but skeptics still question whether inclusion works for all children. To date, most empirical research on inclusion suggests it produces favorable outcomes. When research compares students in inclusive settings with those who remain segregated in specialized programs, the results show mostly positive effects of inclusion on academic achievement (Oh-Young & Filler, 2015) and student social contact (Nakken & Pijl, 2002), without having adverse effects (Wilberger & Palko, 2009). Moreover, research syntheses suggest that inclusive education does not lead to negative consequences for students without SEN (Kalambouka et al., 2007; Szumski et al., 2017). Nevertheless, there may be differential effects for different groups of students and types of inclusion practices (Ruijs & Peetsma, 2009)—both of which depend on teachers’ inclusive classroom practices and, in turn, teachers’ beliefs. Before teachers take on new classroom practices to teach inclusive classrooms, they may first need to change their beliefs about inclusive education, which is a complex and cognitively demanding process (Gregoire, 2003). For many teachers, their existing beliefs may conflict with the underpinning philosophy of inclusive education (Wilson et al., 2016) and can prevent the implementation and sustained use of inclusive reform (Fox et al., 2021). Thus, understanding teachers’ beliefs about inclusive practices gives insights into an important precursor of whether teachers implement inclusive practices or not.

The Role of Teachers’ Belief Systems and the Implementation of Inclusive Reform

According to Gregoire’s (2003) cognitive–affective model of conceptual change, teachers’ belief systems play a major role in how comfortable teachers are with implementing reforms (Liou et al., 2019). If teachers think and feel positive about a set of practices, they are more likely to use those practices in the classroom (Fives & Buehl, 2012). Then, no conceptual change needs to take place and beliefs may stay the same (Gregoire, 2003). However, if a teacher’s prior beliefs and experiences are opposed to the reform approach, those beliefs and experiences may act as a barrier to implementing the reform (Fox et al., 2021). When teachers engage in critical appraisal, they may realize that the reform practices are actually at odds with how they have been teaching for a long time. Being confronted with a reform message that challenges a teacher’s current ideas about instruction (cognitive appraisal) can make the teacher appraise the situation as stressful, resulting in feelings of anxiety (emotional appraisal). Whether or not the teacher feels able to cope with this situation (self-efficacy) will determine whether the reform will be appraised as a challenge or a threat (Gregoire, 2003). Eventually, such negative appraisals can contribute to teacher burnout (Chang, 2009) and teacher turnover (Iancu et al., 2018).

Cognitive Appraisals of Inclusive Education

Cognitive appraisal refers to a person’s cognitive evaluation of an attitude object (i.e., whether it is favorable or unfavorable (Ajzen, 2002)). More precisely, teachers’ cognitive appraisals of inclusive education include beliefs about the effectiveness of including students with diverse SEN in regular classrooms and whether inclusion is viewed positively or negatively (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002). This evaluation builds on teachers’ cognitive representations of inclusive education that reflect teachers’ thoughts about the costs and benefits of inclusion for classroom management, teachers’ own work, and for the students themselves (including those with and without SEN) (Forlin et al., 2010).

Cognitive appraisals of inclusive education affect the perception and the expectations that teachers have for their students, which can have profound consequences on their teaching (Kiely et al., 2015). For example, appraising inclusion as an obstacle often goes along with a deficit view of students at risk for school failure, wherein educational challenges are mainly explained by students’ deficits (Ainscow, 2007). In contrast, the appraisals of inclusion as an opportunity for education build on an approach towards diversity that considers students’ backgrounds as an asset for learning rather than an obstacle (Ainscow, 2005; UNESCO, 2017a). Previous reviews suggest that teachers appraise the inclusion of students with SEN in regular schools in a slightly negative way. Thus, as far as we know today, teachers’ cognitive appraisals have been slightly more deficit-focused than asset-based (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002; De Boer et al., 2011; Scruggs & Mastropieri, 1996).

Emotional Appraisals of Inclusive Education

Compared to cognitive appraisals, emotional appraisals take inclusion to a personal level (Savolainen et al., 2012). Teachers’ emotional appraisals are most likely to occur when their cognitive evaluation of reform indicates that the reform is personally relevant and will impact their well-being (Gregoire, 2003). Whereas some teachers feel threatened by inclusive education because they fear the additional workload (Pearman et al., 1997), anticipate stress (Jenson, 2018), or experience feelings of threat related to a lack of resources (Sharma & Desai, 2002), others feel less concerned regarding inclusion (Forlin et al., 2010). Evidence on teachers’ emotional appraisals varies; typically, teachers range from being only marginally concerned to very concerned about using inclusive practices (e.g., Forlin & Chambers, 2011).

The response teachers have depends on the individual’s appraisal of the controllability and their ability to cope with that situation (Pekrun, 2006). When teachers feel like situations are out of control and/or they cannot cope with the challenge, their appraisals have negative consequences for their emotional state, resulting in burn-out, inability to mobilize cognitive resources, or difficulty choosing instructional strategies effectively (Sutton & Wheatley, 2003; Pekrun et al., 2002; Talmor et al., 2005; Kunter et al., 2013). In turn, this state can affect their students adversely (Frenzel et al., 2021; Aldrup et al., 2018). Given the evidence on the detrimental effects of teachers’ negative emotional appraisals on various teacher, student, and instruction outcomes, one important open question is if and how emotional appraisals can be modified (Sutton & Wheatley, 2003), which turns attention toward understanding self-efficacy beliefs.

Self-Efficacy Beliefs about Implementing Inclusive Education

Self-efficacy beliefs regarding inclusive education refer to teachers’ resources for coping as well as their expectations of being able to support students in specific situations. Teachers are more likely to act if they believe they can successfully accomplish a reform effort (Bandura, 1997), such as inclusion. These self-beliefs serve as a cognitive lens through which teachers evaluate whether or not to engage in efforts to carry out reform practices (Liou et al., 2019).

Teachers with low self-efficacy toward implementing inclusive practices may feel incapable of including students with SEN in their classrooms, and, consequently, make little effort to adapt their teaching to meet the needs of SEN students (Sharma et al., 2012). Many teachers do not feel well prepared for the tasks that can arise in inclusive settings, such as responding to particular difficulties or making adaptations (Florian & Black-Hawkins, 2011), and they experience concern about a lack of personal and material resources to implement inclusion effectively (Sharma et al., 2009). In contrast, higher self-efficacy beliefs about inclusive practices are associated with stronger intentions to teach inclusively (Miesera et al., 2019; Opoku et al., 2020), a stronger willingness to implement specific inclusive practices in their classrooms (Avramidis et al., 2019), and higher self-reported implementation of inclusive teaching practices (Schwab & Alnahdi, 2020).

Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs have been found to be the most influential of the belief constructs for predicting whether or not teachers take action to carry out reform (Liou et al., 2019). For example, teachers’ self-efficacy to implement inclusive practices contributes to teachers’ prospective cognitive appraisals and, even more so, toward their emotional appraisals of inclusive education, based on cross-lagged analyses (Savolainen et al., 2020; Sharma & Sokal, 2015). Beyond this, higher self-efficacy protects teachers from burnout (Evers et al., 2002) and is one of the main psychological resources that can reduce emotional exhaustion in teachers (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2017).

In sum, teachers’ cognitive appraisals, emotional appraisals, and self-efficacy beliefs contribute to the extent to which teachers are likely to implement inclusive education reform in their classrooms. To date, we know that teachers vary in all aspects of their belief system towards inclusive education. However, we do not fully understand what contributes to or produces changes in these belief components. Improving our understanding will help support teachers to perceive the new standards of inclusive education as a new opportunity rather than a threat to existing instructional practice, which in turn will improve the implementation of inclusive practices (Liou et al., 2019).

Do Teachers’ Experiences Create Variation in Teachers’ Belief Systems about Inclusive Education?

Teachers’ experiences inside and outside of classrooms vary, and they relate to their belief systems (Didion et al., 2020; Klassen & Chiu, 2011). The associations are bi-directional: not only can teachers’ beliefs shape teachers’ experiences (for example, beliefs contribute to whether a person decides to study to become a special or regular education teacher), but their experiences can contribute to their beliefs (Fives & Buehl, 2012). One prevalent theme in studies of teachers’ beliefs is the category of teacher type, thus differentiating between (1) teachers with general teaching experience in regular classrooms (i.e., teaching experience with typically developing students) and (2) teachers with specific training and experience as special-needs teachers (i.e., experiences in special or inclusive classrooms).

General Teaching Experience in Regular Classrooms

Teachers’ appraisals of inclusive education may be affected by their preservice education to become a regular education teacher and years of teaching experience in a typical classroom (i.e., how long they have worked as a regular education teacher). With more years of work experience, many actions become automated throughout a teacher’s career, which enables teachers to focus on other aspects of their work (Berliner, 1994). In the beginning, novice teachers report more feelings of work overload (Paquette & Rieg, 2016) and tend to use more avoidant strategies (e.g., withdrawing from sources of stress) than experienced teachers (Sharplin et al., 2011). On the other hand, novice teachers perceive less work-related stress (Klassen & Chiu, 2011) and tend to be more idealistic regarding their perception of teaching than in-service teachers who regard the teaching process more realistically (Anspal et al., 2012). This can lead to over-confidence in preservice teachers, but also to more negative feelings when classroom realities do not match their expectations (Toompalu et al., 2017). To date, it remains an open question whether or not teachers’ years of experience in a regular classroom translate into rather positive or negative appraisals of inclusive education, as the findings have been inconclusive (see Avramidis & Norwich, 2002; De Boer et al., 2011).

Specific Training and Experience in Special Education

Teachers’ preparedness for inclusive education may also vary in light of preservice teachers’ preparation for teaching and their years of experience teaching students with special needs. Special education teachers show more positive beliefs about inclusive education than regular education teachers (Lee et al., 2015). While regular teachers usually have little or no training in how to teach classes with SEN students effectively, special education teachers have knowledge about individual differences and have learned teaching strategies that allow them to adapt to students with SEN. Moreover, they developed their belief system based on classroom experience with teaching students with SEN. As a consequence, special education teachers hold more positive beliefs toward inclusion, which are partly mediated by higher self-efficacy beliefs about teaching in inclusive settings (Desombre et al., 2019). Not only in-service, but also preservice special education teachers tend to have higher self-efficacy beliefs for teaching students with SEN than preservice teachers in regular teacher preparation (Leyser et al., 2011). Of course, it is also possible that persons who are positive about inclusion are more inclined to choose a career in SEN.

Influence of Targeted Interventions

Interventions for pre-service and in-service teachers are designed to create change in people’s beliefs and actions. Among pre-service teachers, interventions typically take the form of courses. Among in-service teachers, these interventions may be programs or courses that are embedded into professional development opportunities. For both pre-service and in-service teachers, the interventions may involve practical experiences in inclusive classrooms and/or practical experiences with students with SEN. Such experiences vary in length from just a couple of days or weeks of training to long-term intervention. To date, findings have been inconclusive (e.g., for initial teacher preparation: (Ajuwon et al., 2015; Rakap et al., 2017); for in-service teachers’ professional development: (Aiello & Sharma, 2018; Sucuoğlu et al., 2015)). Moreover, it is still poorly understood which parts of teachers’ belief systems are affected, and how changes in beliefs are achieved.

To be concrete, envision situations where preservice and in-service teachers are participating in interventions (e.g., coursework, programs) designed to teach them about inclusive education. In these training situations, a teacher may react in one of three ways. Some teachers will have cognitive appraisals of inclusive education that fit with their prior knowledge and experience; their emotional appraisals may result in feelings of pleasantness or curiosity, and they will not perceive the need to reflect on and change their practices. In contrast, other teachers will have cognitive appraisals of inclusive education that reveal incongruity between their current beliefs and the new instructional content. Among these teachers experiencing incongruity, some will have emotional appraisals of concern, worry, and threat about the implementation of inclusive education, whereas others will have emotional appraisals that signal an opportunity to learn new information and grow. What differentiates between these two latter groups? Is it teachers’ point in their career, training as special educator versus regular teachers, or some aspect of the training itself?

Existing studies of inclusive education interventions and teachers’ beliefs provide the raw material for meta-analysis to answer these key questions. As mentioned above, some studies focus on preservice teachers, whereas others study in-service teachers. Some studies examine special education teachers and/or regular education teachers to understand how interventions contribute to belief change. Studies of interventions related to inclusive education also examine the role of field experience in an inclusive classroom, practical experience with people with SEN, and length of interventions—thus setting the stage to consider these features as potential moderators of change in beliefs.

Field Experience in an Inclusive Classroom

Teachers’ field experience in an inclusive classroom creates mastery or vicarious experiences that may shape how teachers think and feel about inclusive education. Providing them with real-world experiences upon which they can base their beliefs, such as field placements and observations, is assumed to foster a more realistic sense of self-efficacy and more realistic beliefs about teaching and learning (Haverback & Parault, 2009). Some studies indicate that preservice and in-service teachers benefit from having the opportunity to gain experience with inclusive education through field experience (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002). Most of these studies embedded field experience in course work (McHatton & Parker, 2013). Mastery experience has been found to be vital in predicting teachers’ self-efficacy (Wilson et al., 2020).

Practical Experience with People with SEN

Teachers’ practical experiences with people with SEN could have shaped their belief system. In line with Allport’s intergroup contact theory, which posits that personal contact is an effective way to reduce prejudice (Allport, 1954), many researchers have argued that teachers develop more positive beliefs about inclusive education when they have regular contact with people in marginalized groups (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002; Parasuram, 2006; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006). Work measuring practical experience with people with SEN typically asks teachers questions about how much time people have spent with individuals with different disabilities as a way of assessing the amount of contact.

Length of Intervention

Training experiences and interventions range in length, with some being short workshops of several days (e.g., 5 days in the study by Carew et al., 2019) and others being long-term interventions (e.g., 2 years in the study by Sharma et al., 2008). Existing research on the length of interventions suggests that the effectiveness of interventions increases with their length (Bezrukova et al., 2016). On the other hand, other meta-analyses indicate that shorter teacher interventions lead to even higher effects (e.g., Egert et al., 2018), or that length did not affect the effectiveness of teacher interventions at all (e.g., Gesel et al., 2021). Synthesizing information about how the length of interventions relates to teachers’ beliefs can inform the development of effective interventions for future use.

Existing studies vary in who receives training (preservice or in-service teachers, special education or regular education teachers) and what is considered a critical component of the delivery (field experience in inclusive classrooms, practical experience with people with SEN, short- or long-duration trainings). To date, we still have a limited understanding of the characteristics that make such interventions most effective (Lautenbach & Heyder, 2019). Using longitudinal designs, one can investigate the effects of interventions in teacher preparation programs and professional development on the development of teachers’ belief systems. Such studies provide the ideal raw material for meta-analysis.

The Present Study

The existing work leads us to take a three-pronged approach to examine beliefs by focusing on cognitive and emotional appraisals of inclusion as well as teachers’ own self-efficacy in teaching inclusive classrooms. The focus on teachers’ cognitive appraisals of inclusive education is important because these evaluations affect the teachers’ perception of their students (Woolfolk Hoy et al., 2006), influence teachers’ classroom practice (Kiely et al., 2015), and teachers’ well-being (Buehl & Beck, 2015). Examining teachers’ emotional appraisals of inclusion is important because it affects teachers’ coping processes (Gregoire, 2003; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Finally, examining self-efficacy beliefs about teachers’ capabilities and the outcomes of their efforts is important because it can affect their classroom behavior (Klassen & Tze, 2014). As described above, these belief systems are interconnected and malleable.

With this meta-analysis, we aim to test how teachers’ cognitive and emotional appraisals and self-efficacy beliefs about inclusive education vary as a function of their experiences. Furthermore, we aim to clarify which elements of teacher training have an impact on teachers’ beliefs about inclusive education.

RQ 1 How do teachers think and feel about inclusive education and how does point in their career (pre-service versus in-service) contribute to their belief systems?

In the first step, we examined teachers’ belief systems about inclusive education using the full sample of 102 studies from 40 different countries. To this end, we quantified teachers’ cognitive appraisals, emotional appraisals, and self-efficacy beliefs about teaching inclusive classes and identified whether the point in teachers’ careers (preservice vs. in-service teachers) can explain variation in these beliefs.

RQ 1.1 How do teachers cognitively appraise inclusive education, and how does this vary depending on the point in teachers’ careers (pre-service versus in-service)?

Many studies (m = 102) have investigated teachers’ beliefs (i.e., cognitive appraisals) about inclusive education, but the results are inconclusive. Literature reviews (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002; De Boer et al., 2011) indicate that teachers vary in their views about inclusive education, with some research showing that teachers hold positive beliefs, whereas others show that teachers hold negative beliefs. Some studies show that teachers have favorable views on average (e.g., Avramidis et al., 2000; Wilson et al., 2016), whereas in other studies, teachers held negative (Rapak & Kaczmarek, 2010; Thaver & Lim, 2014) or neutral views about inclusive education, meaning that they neither agree nor disagree with statements such as “most children with exceptional needs are well behaved in integrated education classrooms” (Galovic et al., 2014; Memisevic & Hodzic, 2011). Based on existing work, we hypothesized that cognitive appraisals would be near the mid-range of the scale (suggesting room for growth). Further, we expected cognitive appraisals about inclusive education would be more favorable among in-service teachers compared to preservice teachers because in-service teachers base their beliefs on a broader range of work experiences than preservice teachers (Berliner, 1994; Toompalu et al., 2017).

RQ 1.2 How do teachers emotionally appraise inclusive education, and how are these emotional appraisals moderated by the point in the teachers’ career (pre-service versus in-service)?

Only a few studies (m = 23) have investigated teachers’ emotional appraisals of inclusive education. While some studies indicate that teachers feel moderately concerned (Forlin & Chambers, 2011; Sharma & Sokal, 2015), others report that teachers have many concerns about the consequences of including children with SEN in their classrooms (Savoleinen et al., 2011). Therefore, we hypothesized that teachers would be, on average, moderate and near the midpoint of the scale in their emotional appraisals of inclusive education, indicating hesitant feelings toward inclusive education. Further, we expected that emotional appraisals would be more positive among in-service teachers because they have more experience managing work overload (Paquette & Rieg, 2016) and possess more effective coping strategies than preservice teachers (Sharplin et al., 2011).

RQ 1.3 How self-efficacious are teachers toward implementing inclusive education, and how is self-efficacy moderated by teachers’ point in their careers (preservice versus in-service)?

Only a few studies (m = 24) examined self-efficacy for inclusive education. In general, we hypothesized that teachers would rate near the midpoint of the scale for self-efficacy beliefs, suggesting room for growth before teachers adopt inclusive practices readily. Based on the evidence that shows higher self-efficacy beliefs for preservice than for in-service teachers (Ismailos et al., 2019; Tümkaya & Miller, 2020), we hypothesized higher self-efficacy among preservice than in-service teachers because preservice teachers tend to overestimate their abilities given their limited experience (Anspal et al., 2012; Ismailos et al., 2019).

RQ 2 Do special and regular education teachers’ belief systems about inclusive education differ?

In the second step, we investigated the differences in belief systems about inclusive education among special and regular education teachers given that these two types of teachers have different training and subsequent experience in the classroom. Quite a few of the retrieved studies (m = 18) provided data that directly compared the beliefs of special and regular education teachers, thus creating an opportunity to conduct a separate meta-analysis with these 18 studies to compare differences in beliefs by teacher type. Based on the assumption that initial teacher preparation has an impact on teachers’ formation of their belief systems, we expected special education teachers to hold more affirmative cognitive appraisals (Lee et al., 2015), more confident emotional appraisals (Schields, 2020), and higher self-efficacy beliefs about teaching inclusive classrooms (Desombre et al., 2019; Leyser et al., 2011) than regular education teachers.

RQ 3 How malleable are beliefs about inclusive education following intervention (i.e., training, teacher preparation, professional development)?

Finally, we examined the contribution of interventions about inclusive education to changes in teachers’ belief systems in a set of 17 studies. For this question, we defined “intervention” broadly to include preservice education courses and training in professional development programs. Since previous literature reviews have suggested that training teachers in inclusive education affects their beliefs (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002), we hypothesized that programming targeting inclusive education would contribute to more affirmative cognitive appraisals (Lautenbach & Heyder, 2019), more confident emotional appraisals (Sharma & Sokal, 2015), and higher self-efficacy beliefs (Sharma & Sokal, 2015). To test this hypothesis, we examined the contribution of interventions on belief using 17 studies on cognitive appraisals, 7 on emotional appraisals, and 4 on self-efficacy. We did not expect this effect to be moderated by the teachers’ point in their careers, as there was no indication in the literature that preservice teachers would benefit more from training than in-service teachers or vice versa. However, we hypothesized that this effect would be moderated by intervention characteristics such that the effects of training would be higher under certain conditions: (a) when the training involved practical experience in inclusive classrooms (McHatton & Parker, 2013), (b) when the training involved practical experience with people with SEN (Parasuram, 2006), and (c) when the training was longer in duration (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002). To understand the contribution of training involving practical experience, we controlled for the length of the teacher intervention in predicting outcomes (Kennedy, 2016).

Method

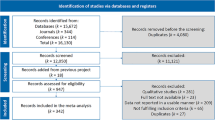

For this meta-analysis, we followed the Meta-Analysis Reporting Standards (MARS; American Psychological Association, 2008) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. In this section, we: (a) describe our literature search and inclusion criteria, (b) the data extraction and coding of the retrieved studies, (c) the analytic strategy, including our approach to calculating effect sizes, and (d) the meta-analytic methods used in this study.

Literature Search and Inclusion Criteria

We conducted a systematic search to locate primary studies on preservice and in-service teachers’ beliefs about inclusive education. Since international agreements on inclusive education and education for all led to global efforts on implementing inclusion in the 1990s and later (Werning et al., 2016), we searched for international studies published between January 2000 and January 2020. We searched for titles and abstracts containing the terms inclusi*, special educational needs, divers*, and heterogen*, each in combination with teacher in the databases PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, and Web of Science.

To be included, studies had to meet seven criteria. Studies had to: (a) assess belief systems about inclusive education, (i.e., cognitive appraisals, emotional appraisals, or self-efficacy to teach inclusive classes); (b) include preservice or in-service teachers; (c) be carried out in a formal educational context, and the studies ranged from focusing on preschool through secondary school; (d) contain the statistical information needed to calculate standardized means or effect sizes; (e) report on measurable outcomes of the teacher education course on teachers’ beliefs about inclusive education; (f) indicate the scale of the measurement instrument in order to standardize the mean scores; and (g) be published in English. (See PRISMA Table S1 (online only) in the Appendix for more detailed information on the methodology of the literature search, the coding, and the computation of the meta-analysis.)

After omitting duplicate data, the initial search yielded 4737 hits in total. A first screening of titles eliminated those that did not meet the eligibility criteria, yielding 469 records that were further screened based on the abstract. That screening involved another check of eligibility and led to the exclusion of qualitative studies that did not provide any data. Out of the 146 full-texts which were assessed for eligibility based on the seven criteria mentioned above, 15 studies had to be excluded because they did not provide the necessary data to compute effect sizes.Footnote 1 Furthermore, 29 studies were excluded as they included only qualitative data analyses that did not serve to compute effect sizes. That resulted in 102 studies that met the abovementioned eligibility criteria and were selected for more detailed coding (see Fig. 1).

We coded each selected full text according to a coding scheme (see Table 1) to ensure greater accuracy when analyzing the studies. From the 102 studies, we retrieved 191 effect sizes based on a total sample of 40,898 teachers that were entered into the meta-analysis.

Data Extraction and Coding

A data coding system was developed, capturing information about each study, all potential moderator variables, and the statistical parameters, with the goal of establishing high accuracy in the coding process. We coded study characteristics, the type of outcome variable, statistical parameters, and characteristics of the interventions that were administered to preservice or in-service teacher programs. Table 1 shows the information coded from the full texts of the thematically relevant studies found in the databases, which matched the terms we used in our search. Each study was coded by two raters. The coders underwent intensive coding training that included communal coding and discussion of coding results. Interrater agreement was found to range between 89 and 100%. Disagreement was resolved through discussion. Regular checks of interrater reliability were carried out throughout the coding process, showing no time-related decline in agreement.

Analytic Strategy and Calculation of Effect Sizes

RQ 1 How do teachers think and feel about inclusive education and what are the experiences that contribute to their belief systems?

As meta-analysis can only capture one outcome variable at a time, three separate meta-analyses of standardized mean scores were conducted to calculate average weighted standardized mean values for teachers’ cognitive (RQ 1.1) and emotional appraisals (RQ 1.2) and self-efficacy beliefs (RQ 1.3). In each meta-analysis, moderator analyses were conducted in terms of meta-analytic regression analysis to determine whether teachers’ beliefs vary as a function of the teachers’ point in their careers (preservice vs. in-service teachers). This entailed between-study comparison as most studies reported means for only one sample, while few studies reported between-group differences.

Meta-analysis of mean scores required that all studies’ results be expressed in a standardized form (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). This means that results had to be recoded into the same scale. While one-third of the data collections were carried out with self-developed questionnaires to assess teachers’ cognitive appraisals (m = 29), the instruments that most of the studies applied were the ATIES (Wilczenski, 1995; example item: Students who cannot control their behavior and disrupt activities should be in regular classes “) (m = 13), and the SACIE (Loreman et al., 2007; example item: “Students who need an individualized academic program should be in regular classes”.) (m = 11), the ORI (Antonak & Larrivee, 1995; Larrivee & Cook, 1979; example item: “The student with a disability will probably develop academic skills more rapidly in a regular classroom than in a special classroom.”) (m = 10), and the TATIS (Cullen et al., 2010; example item: “All students with mild to moderate disabilities should be educated in regular classrooms with non-handicapped peers to the fullest extent possible.”) (m = 7). These items deal with the feasibility of a regular class placement for students requiring physical, academic, behavioral, or social accommodations. Teachers are asked to indicate their attitudes on 6-point scales with strongly agreed/strongly disagreed anchors (Likert scale). Low scores on the scale indicate less favorable beliefs toward inclusive education; high scores on the scale indicate more favorable beliefs. Thus, even a mid-range answer (“agree nor disagree”) reflects a neutral belief about inclusion that may interfere with a teacher’s uptake of inclusive practices.

The score for beliefs about inclusive education was most frequently operationalized on a five-point scale, with 1 being the minimum and 5 being the maximum. All these scales assessed teachers’ agreement to the items, ranging from strong disagreement up to a strong agreement. For studies in which a different scale was employed, mean scores were converted into the same 5-point scale metric using the following formulas, in which \(\mathrm{Min}\) indicates the minimum value of the study’s scale (usually 1), \(\mathrm{Max}\) being the maximum value of the study’s scale, and \(\mathrm{Mean}\) being the reported mean value. After applying these formulas, the means and standard deviations can be compared across studies and should all be interpreted in terms of a 1- through 5 five-point scale.

High scores of cognitive appraisals reflect a positive appraisal of inclusion, and high scores for self-efficacy indicate a positive belief that teachers can teach inclusive classrooms. In contrast, values from the emotional appraisal measures were recoded so that high scores of emotional appraisals indicated a low level of concern, thus positive emotional appraisals.

RQ 2 Do special and regular education teachers’ belief systems about inclusive education differ?

Since a sufficiently large number of studies reported between-group differences between special and regular education teachers, we conducted a separate meta-analysis for which we computed Cohen’s \(d\) to indicate group differences between special and regular education teachers. This analysis was only conducted for cognitive appraisals because there was an insufficient number of studies that reported means by sub-group for emotional appraisals and self-efficacy. To investigate group differences utilizing within-study variation, for the 27 studies that reported separate estimates for teachers with special and regular education, the effect size Cohens’ \(d\) was calculated, which represents the standardized mean difference between two groups divided by the pooled standard deviation (Hedges & Olkin, 1985). As not all studies reported reliability scores, effect sizes were not adjusted for reliability (Hunter & Schmidt, 1990). This decision rested on the assumption that the effect sizes would be more comparable if all were left unadjusted instead of adjusting some but not all effect sizes (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001).

RQ 3 How malleable are beliefs about inclusive education following intervention (i.e., teacher preparation or professional development)?

To examine the effects of intervention on teachers’ cognitive appraisals, a meta-analysis was conducted with the 30 retrieved intervention studies, and we computed Cohen’s \(d\) to indicate group differences between pretest and posttest scores, with a positive effect size indicating a positive belief change. In addition, 12 studies reported intervention effects on teachers’ emotional appraisal and five studies on teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs.

Meta-analytic Method

For each research question, an average effect size was computed to determine the overall mean effect. Effect sizes resulting from studies with different sample sizes would not predict the treatment effect with the same precision. Thus, when combining effect sizes across studies, effect sizes were weighted by the inverse of their estimated sampling variance \({V}_{i}\) to assure more precise estimates of the population parameter such that larger samples were weighted more than smaller samples (Rosenthal et al., 1994; Morris & DeShon, 2002). Because we regard the effect estimates that are included in this meta-analysis as a random sample from the universe of all potential effect estimates, we added an additional variance component \({\widehat{\tau }}^{2}\) that reflects the estimated population distribution of effect estimates (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001; Overton, 1998). We hence weight each estimate \(i\) by the inverse of its total variance, calculated as \({\mathrm{weight}}_{i}=\frac{1}{{V}_{i}+{\widehat{\tau }}^{2}}\).

In some cases, dependencies existed between effect estimates from the primary studies, as multiple estimates on the same samples were given (e.g., when scores from two different beliefs questionnaires were assessed within the same teacher sample). Ignoring these correlations increases the risk of Type I error. Recent meta-analytic procedures have addressed such data structures by applying hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) or robust variance estimation (RVE) (Hedges et al., 2010). We selected RVE because of several advantages: (a) it requires fewer assumptions about the distribution of the data, (b) it builds on adjusting standard errors (in a similar way as, for example, heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation consistent (HAC) standard errors), and (c) it does not require exact knowledge on the covariances between the effect sizes from the same clusters (Tanner-Smith & Tipton, 2014; Tipton & Pustejovsky, 2015).

Following Hedges et al. (2010), an RVE meta-analysis on mean differences gives approximately correct confidence intervals independently of the number of included clusters and estimates per cluster. When computing the weighted average effect sizes, we conduct RVE assuming a correlation between estimates from the same cluster of \(\rho =.80\) as recommended by Tanner-Smith and Tipton (2014). In RVE, one assumes a certain correlation between the effect estimates within clusters (here: 0.80), which is the same for each cluster. If the assumed correlation deviates from the true correlation, this does not lead to bias, but only to a loss of efficiency. We conducted sensitivity tests with \(\rho\) values varying from \(\rho = 0.0\) to \(\rho = 0.9\), which demonstrated that the results were robust to the choice of \(\rho\). For the meta-analyses on teachers’ self-efficacy (RQ 1.3) and on the effectiveness of teacher intervention on emotional appraisals and on self-efficacy, there was only one estimate for each cluster. As a result, for these three analyses, no RVE could be conducted (see Table 2).

For meta-regression with cognitive appraisals about inclusive education as the dependent variable, we again used RVE analyses. Hedges and colleagues (2010) show that, especially when the number of included studies is not very large, confidence intervals from RVE meta-analyses tend to be incorrect when a few clusters contribute multiple estimates and almost all clusters contribute only one estimate. This is the case for our other outcomes (except RQ 1.1). Because we mostly have categorical covariates in our analyses, the amount of between-cluster variation in the values of the covariates is limited. As a result, we use random effects meta-regression for these outcomes.

We used two methods to investigate whether publication bias affected our results. Publication bias results from an underrepresentation of smaller studies with lower effect sizes and non-significant results. First, a funnel plot was created to provide a visual measure of publication bias by plotting each study’s weighted average effect size on the x-axis and its corresponding standard error on the y-axis. An asymmetric funnel plot would point to a correlation between the effect size and the precision of the study. Second, Egger’s test of the intercept was computed to perform a linear regression of the effect estimates on their standard error by weighting by 1/(variance in the effect estimate) (Egger et al., 1997). Both, the funnel plot and Egger’s test were conducted for each meta-analysis separately.

All analyses were conducted in Stata, version 16. For RVE meta-analyses, we employed the robumeta command.

Results

We start by reporting on the characteristics of the sample of studies and estimates and then describe the occurrence of outliers and results of the analysis for publication bias. In the next step, we present an overview of teachers’ cognitive appraisals, emotional appraisals, and self-efficacy beliefs regarding inclusive education (RQ 1), and then describe the corresponding moderator analysis examining teachers’ point in their career (preservice versus in-service). Then, we present the meta-analysis on within-study variance about differences between special and regular education teachers’ beliefs (RQ 2). Finally, we show the effects of an intervention on belief change from pretest to posttest and describe how this is (or is not) moderated by point in a teachers’ career, field experience in inclusive classrooms, practical experience with people with SEN, and length of the intervention (RQ 3).

For the interpretation of all analyses, a positive estimate indicates positive cognitive appraisals, positive emotional appraisals, or high self-efficacy beliefs (RQ 1), higher effects for special education teachers compared to regular education teachers (RQ 2), or an increase in positive beliefs about inclusion from pretest to posttest (RQ 3).

Data Description

In total, k = 191 estimates from c = 130 correlated groups (clusters) were extracted from m = 102 primary studies. Table 3 displays the frequencies of characteristics per primary study. Table A2 in the Appendix provides an overview of study characteristics and estimates per study.

Characteristics of Included Studies

As can be seen in Fig. 2, the number of studies of teachers’ belief systems about inclusive education rose continuously in the last two decades and then declined within the last 5 years. The studies were carried out in 40 different countries all over the world, 17 of which have been categorized as low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) according to World Bank classifications (World Bank, 2022). More than 34% of the effect sizes result from studies conducted in LMICs. Most data collections took place in the USA (m = 17), Australia (m = 11), and Canada (m = 8), and more than one-third of the studies were conducted across non-OECD countries (m = 37). Slightly more than half of the studies focused on in-service teachers (k = 91); the other half on preservice teachers (k = 72). From the k = 117 estimates that specified the type of school, k = 93 estimates resulted from studies carried out with preschool or primary school teachers, and k = 24 with secondary school teachers.

In almost half of the studies, the SEN was not specified, but teachers were asked about their cognitive appraisals of inclusive education in general (k = 90). For the remaining studies, the majority referred to appraisals of the inclusion of students with non-physical SEN (k = 64), and the remaining studies focused on the inclusion of students with physical SEN (k = 37).

Outliers

Extreme effect sizes deviating from the effect size distribution are less representative of the full sample and can influence meta-analytic statistics disproportionately because they estimate a different population mean than the mean that is estimated by the rest of the effect size distribution (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). Outliers should therefore be eliminated from the analysis or should be adjusted. Following the procedure of Lipsey (2009) and Tukey (1977), we adjusted effect sizes that were more than 1.5 times the interquartile range beyond the 25th or from the 75th percentile, to the respective inner fence value. In the meta-analysis of mean scores for teachers’ cognitive appraisals and self-efficacy, no outliers were found that needed adjustment. Regarding teachers’ emotional appraisals, one outlier was discovered beyond the 25th percentile (Cologon, 2012) and adjusted to the lower bound.

Publication Bias

We used funnel plots and Egger’s test to examine whether a publication bias affected our results.

RQ 1 Overview of Belief Systems and Belief Systems Based on Teachers’ Point in Their Career.

The resulting funnel plots for scores for teachers’ cognitive appraisals, emotional appraisals, and self-efficacy beliefs about inclusive education did not indicate a publication bias (see Fig. 3). The results of the Egger tests confirmed the symmetry of the funnel plots. The intercepts did not differ significantly from zero (cognitive appraisals: β = 0.04, SE = 0.24, z = 0.15, p = 0.88; emotional appraisals: β = 0.38, SE = 0.61, z = 0.62, p = 0.54; self-efficacy: β = 0.56, SE = 0.74, z = 0.76, p = 0.45), which suggests no publication bias present in these data sets.

RQ 2 Differences Between Special and Regular Education Teachers.

Similarly, the funnel plots for the within-study meta-analysis comparing the beliefs between teachers trained vs. not trained in SEN (see Fig. 4) and the Egger tests did not suggest a publication bias (β = − 0.70, SE = 0.65, z = − 1.07, p = 0.28).

Funnel plots of publication bias among effect sizes for the difference in the cognitive appraisal of inclusive education among special education vs. regular education teachers and of publication bias among teacher training effect sizes. The standard error is presented on the y-axis and the weighted mean effect size on the x-axis. Black dots represent the observed data points

RQ 3 Malleability of Belief Systems Following Intervention.

A similar funnel plot was found for the within-study comparison represented by the effect sizes of intervention studies (see Fig. 4). Results of the Egger tests indicate that there were no small-study effects present (cognitive appraisals: β = − 1.05, SE = 0.81, z = − 1.30, p = 0.19; emotional appraisals: β = − 1.35, SE = 1.57, z = − 0.86, p = 0.39; self-efficacy: β = − 0.59, SE = 1.24, z = − 0.48, p = 0.63).

How do Teachers Think and Feel about Inclusive Education and Does Point in their Career Moderate their Belief Systems?

We carried out a meta-analysis on the mean value of cognitive appraisals, emotional appraisals, and self-efficacy to shed light on teachers’ belief systems about inclusive education, and to understand whether teachers’ belief systems vary as a function of experience (i.e., teachers’ point in their career).

Teachers’ Cognitive Appraisals and How They Vary Based on Point in Their Career

We expected to find an average score for cognitive appraisals in the mid-range of the scale, and we hypothesized average scores would be higher among in-service than preservice teachers. The overall mean for teachers’ cognitive appraisals included in the meta-analysis was 3.18 (SE = 0.06, c = 130) on a 5-point-scale. Thus, as expected, across all studies under investigation, teachers’ cognitive appraisals were near the midpoint in the surveys. In a measure of cognitive appraisals, for example, this would mean that, on average, they neither agreed nor disagreed with a statement like, "Students who cannot control their behavior and disrupt activities should be in regular classes” (example item from the Attitudes Toward Inclusive Education Scale; Wilczenski, 1992, 1995). However, the data showed considerable variation (see Table 4). This distribution was not skewed, and teachers appeared to use the full range of the scale.

Besides the weighted average estimate, we investigated the degree of heterogeneity among the estimates. The variability between the effect estimates \(({\tau }^{2}\)) was 0.08, suggesting that there was variation in the true distribution of standardized means and that the effect likely varies as a function of moderators. Given this heterogeneity in the standardized means, we tested whether the standardized means of teachers’ cognitive appraisals of inclusive education varied systematically according to teachers’ general classroom experience (k = 72 preservice teachers; k = 91 in-service teachers). Contrary to our hypothesis, estimates did not differ between preservice and in-service teachers, B = 0.03, SE = 0.11, p = 0.81.

Teachers’ Emotional Appraisals and How They Vary Based on Point in Their Career

We hypothesized a medium average score for emotional appraisals and expected that emotional appraisals would be higher among in-service than preservice teachers. We retrieved a subsample of k = 35 estimates (resulting from 23 studies and 32 clusters) that provided mean scores measuring teachers’ emotional appraisals about teaching inclusive classes. Using RVE meta-analysis, the results based on the average across all studies in the subsample showed an overall standardized mean of 3.17 (SE = 0.10) on a 5-point scale, which demonstrated moderate concern about teaching inclusive classes, on average. For example, on a measure of emotional appraisals, this would mean neither agree nor disagree with a statement such as “I am concerned that I will be more stressed if I have students with disabilities in my class.” (example item from the Concerns about Inclusive Education Scale; Sharma & Desai, 2002). The small \({\widehat{\tau }}^{2} < 0.001\) indicated that standardized mean scores did not differ across studies. Consequently, no moderator analysis was conducted as—against our hypothesis—there was no statistical indication that scores of preservice and in-service teachers would differ.

Teachers’ Self-efficacy Beliefs and How They Vary Based on Point in Their Career

We expected to find a medium-average score for self-efficacy beliefs, with preservice teachers scoring higher than in-service teachers. We found a subsample of k = 31 estimates (24 studies, 31 clusters) that provided additional data on teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs regarding teaching inclusive classes. Using standard random effects meta-analysis, the overall standardized mean averaged across all studies of this subsample was 3.40 (SE = 0.14), suggesting that teachers feel somewhat self-efficacious toward implementing inclusive education. For example, on a measure of efficacy, that means they would respond between “disagree somewhat” and “agree somewhat” with a statement such as “I am confident in designing learning tasks so that the individual needs of students with disabilities are accommodated" (example item from the Teacher Efficacy for Inclusive Practice Scale; Sharma et al., 2012). However, a test for homogeneity suggested that this estimate likely differed as a function of moderator variables (Q = 80.28; p < 0.001). Consequently, we compared the self-efficacy beliefs between in-service (k = 17) and preservice (k = 11) teachers. In line with our assumption, self-efficacy beliefs were found to be higher for preservice than for in-service teachers, B = 0.55, SE = 0.27, p = 0.04.

Do Special and Regular Education Teachers’ Belief Systems About Inclusive Education Differ?

We assumed to find more positive cognitive appraisals, more confident emotional appraisals, and higher self-efficacy beliefs among special education than among regular education teachers. To test this, we performed a within-study comparison meta-analysis with a subset of k = 27 effect sizes (18 studies; 20 clusters) that reported estimates separately for teachers with and without training in special education. For each study, the standardized mean difference d (Cohen, 1988) was computed to assess differences between special and regular education teachers’ cognitive appraisals.Footnote 2 As hypothesized, teachers with (M = 3.39, SE = 0.16) and without special education training (M = 3.23, SE = 0.16) differed significantly in their cognitive appraisals of inclusive education, with teachers with special education training being significantly more affirmative than regular teachers, d = 0.41, SE = 0.09, p < 0.001 (see Fig. 5). The between-study variability τ2 was < 0.001, indicating homogeneity among the effect sizes.

How Malleable Are Beliefs About Inclusive Education Following Intervention?

We tested the hypothesis that participating in interventions on inclusive education in teacher preparation and professional development would result in more affirmative cognitive appraisals, more positive emotional appraisals, and higher self-efficacy beliefs (Sharma & Sokal, 2015). We did not expect this effect to be moderated by teachers’ point in their careers. However, we expect effects to be higher when the intervention involves practical experience in inclusive classrooms, practical experience with people with SEN, and an increasing length of the intervention.

Studies were coded along the coding categories (see Table S3 for a detailed coding (online only)). Effect sizes of the pre-post gain were computed across the k = 30Footnote 3 effect sizes from the intervention studies (m = 17; c = 22) to investigate the effects of teacher education that addressed teachers’ beliefs about inclusive education (see Table 5 for average mean effect sizes).

Intervention Effects on Cognitive and Emotional Appraisals and Self-efficacy Beliefs

The average mean effect size for the increase in cognitive appraisals of d = 0.63 (SE = 0.15) was found across all intervention studies, suggesting a substantial effect of interventions on teachers’ appraisals of inclusive education (see Fig. 6). The \({\widehat{\tau }}^{2} =\) 0.21 indicates heterogeneity in effect sizes; thus, we conducted moderator analyses (see Table 6).

We also found a similar effect on change in teachers’ emotional appraisals across the 12 studies (m = 7; c = 12) that reported on pretest and posttest scores for teachers’ emotional appraisals, d = 0.63, SE = 0.18 (see Fig. 7). Findings showed that teachers reported less concern with inclusion after the intervention than before.

The effects of teacher intervention on teachers’ self-efficacy were investigated in five studies (m = 4; c = 5). The analysis revealed a high intervention effect on the development of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs, d = 0.93, SE = 0.17.

Moderator Effects of Teachers’ Field Experience in an Inclusive Classroom, Teachers’ Personal Experience with People with SEN, and Length of the Intervention

Moderator analyses were only indicated for cognitive appraisals, as for emotional appraisals and for self-efficacy, we found only low variation of effects across studies, \({\widehat{\tau }}^{2}<\) 0.001. With regard to teachers’ general teaching experience, in line with our assumption, we did not find effects to differ between interventions for in-service (k = 14) compared to preservice (k = 16) teachers, B = 0.31, SE = 0.25, p = 0.22.

As to practical experience in inclusive classrooms, in accordance with our hypothesis, interventions that included a practicum in inclusive classrooms (k = 6) were more effective than interventions without opportunities for practical experience, B = 0.79, SE = 0.29, p = 0.007. Against our hypothesis, no such difference was found for interventions that included contact experience with a person with SEN (k = 5), B = 0.13, SE = 0.33, p = 0.70. Contrary to our expectation, no moderator effect was found for the length of the intervention, assessed by means of the total number of training hours across all training sessions, B = 0.003, SE = 0.002, p = 0.86.

Discussion

The trend toward inclusive education is a worldwide phenomenon that has occurred over the past several decades. Despite being a promising approach, its implementation is challenging for teachers. For inclusive education to be implemented effectively, teachers need to believe that all students belong in a regular classroom (Specht et al., 2016). This article provides the first meta-analysis that uses studies from 40 countries to investigate three different components of teachers’ belief systems about inclusive education. In doing so, the findings explain differences between groups of teachers (preservice versus in-service, special education versus regular) and evaluate the effects of interventions on aspects of beliefs toward inclusive education. The meta-analysis uses 191 effect sizes based on research from 40,898 teachers from around the world and includes research from low-, middle-, and high-income countries. We identified six key findings that inspire further research on teachers’ belief systems and their malleability. Such findings have implications for the field of inclusive education and have broader implications for educational practice and policy related to inclusive education as well as other reforms (see Table 7 for an overview of the results).

On Average, Teachers Neither Endorse nor Reject Inclusive Education

The mean values of teachers’ beliefs about inclusive education were found to be around the midpoint, on average. Similarly, previous qualitative research syntheses found that, on average, teachers were neither strongly negative nor particularly favorable towards inclusive education (e.g., De Boer et al., 2011). There are several plausible explanations for why teachers tend to rate toward the middle of the scale. One possibility is that many teachers are rather indifferent toward inclusive education and therefore chose the midpoint of the scale. Yet another possibility is that teachers choose the mid-point of a scale, indicating that teachers do not have a strong opinion (O’Muircheartaigh et al., 1999) or lack the cognitive effort required to decide upon a clear answer (“satisficing”) and therefore rate towards the center of the scale (Saris & Gallhofer, 2007). Further, some teachers may simply use the middle category of a scale as a “don’t know” category (Sturgis et al., 2014). Regardless of the explanation, teachers’ average scores toward the middle of the scale shed light on practitioners’ and policymakers’ making decisions about inclusive education.

Given international trends toward inclusive education, what does it mean that teachers, on average, hold views that are toward the middle of the scale? Most likely, it means that many teachers have beliefs that may be interfering with their ability to use inclusive practices. For example, if teachers tend to be negative or neutral about inclusive education, it can be difficult to reach these teachers in professional development situations. Following Gregoire (2003), these teachers may perceive the implementation of inclusion as a stressful situation—in particular, negative emotional appraisals (combined with a perception of low resources) may lead to a threat appraisal, which will result in heuristic processing (e.g., immediate responses, mental shortcuts). Following this logic, even scores at the midpoint for cognitive appraisals, emotional appraisals, and self-efficacy—although they may seem neutral and harmless at first glance—can pose a problem and lead to low levels of implementation of inclusive education.

In-service Teachers Need Stronger Self-efficacy Beliefs

Teachers need a strong sense of self-efficacy to feel capable of overcoming challenges and processing a new reform message (Gregoire, 2003). However, our results show that, on average, teachers hold self-efficacy beliefs toward inclusion that suggest only modest efficacy in teaching students with SEN. Further, we even found that preservice teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs are significantly higher than those of in-service teachers. This is in line with earlier research on changes in self-efficacy beliefs in teachers’ careers and indicates that many novice teachers, due to their inexperience, hold rather unrealistic beliefs about their competence (Anspal et al., 2012). Importantly, this means that in-service teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs are even lower than the average mean found in our meta-analysis. Given that increases in self-efficacy are likely to lead to the formation of more positive cognitive and emotional appraisals and that all three can increase the chance that teachers carry out inclusive practices (Savolainen et al., 2020), the need arises to support teachers—in particular, in-service teachers—to boost self-efficacy beliefs about inclusive education.

Special Education Teachers Experience More Positive Cognitive Appraisals Toward Inclusion

Teacher type (special education versus regular education teacher) explained variation in teachers’ cognitive appraisals. Special education teachers held more positive views toward inclusion than regular teachers. These findings suggest that affirmative beliefs may not develop on their own, but rather as a consequence of specific, preservice education related to special education. This supports the assumption that teachers may not be “born to be a good inclusive educator” but can be trained to become one (see Klassen & Tze, 2014). Given the importance that teachers’ beliefs and their resources have for their challenge or threat appraisal, training teachers in implementing inclusive education seems to have a strong potential to foster teachers’ approach intention. Yet, it is difficult to make a causal inference here in that there may be specific qualities about teachers who choose to train in special education instead of regular education that differ even before their teacher preparation program.

Belief Systems About Inclusive Education Can be Improved Through Interventions

One of our goals has been to identify specific intervention characteristics that moderate its effectiveness. Unfortunately, there were not enough studies to test moderation for all four moderators and all three belief outcomes. Still, existing studies allowed us to examine moderator effects for cognitive appraisals. Analyses revealed several key findings: (1) the interventions were equivalently efficacious in predicting cognitive appraisals regardless of teachers’ point in their teaching career, (2) interventions involving practical experience in inclusive classrooms were more effective, (3) practical experience with people with SEN did not moderate outcomes, and (4) intervention length did not moderate outcomes. Taken together, these results are encouraging because they give insights about training opportunities that support changes in teachers’ beliefs, and in turn, can help teachers become inclusive educators.

Practical Experience in Inclusive Classrooms Forecasts Cognitive Appraisals But Not Point in One’s Career or Practical Experience with People with SEN

Specific practical experience in the inclusive classroom moderated the effectiveness of teacher intervention. More precisely, effect sizes were higher for interventions that included fieldwork in an inclusive classroom. Yet, there were no differences in the relation between the intervention and cognitive appraisals depending on the point in a teacher’s career (preservice or in-service) or based on a teacher’s past experience spending time with people with SEN.

Thus, the experience of spending time in an inclusive classroom brings about belief change (see also Sharma et al., 2008). This finding is supported by previous research, reflecting a positive association between teachers’ experiences in inclusive classrooms and their cognitive appraisals of inclusive education (Cansiz & Cansiz, 2017; Hong et al., 2018). To understand the importance of practical experience, it is worth reflecting on the meaning of cognitive appraisals. In essence, having a positive cognitive appraisal means that teachers see the feasibility and desirability of including students with behavior problems or needing individualized academic programs in regular classrooms. It is plausible that practical experience in inclusive classrooms gives teachers an opportunity to understand some of the benefits of inclusion for students with SEN. Teachers may see and understand how mentor teachers can handle challenging situations effectively. Such practical experiences appear to boost teachers’ perception that students needing physical, academic, behavioral, or social accommodations can excel in typical classrooms. This finding may be useful for other reform efforts in that when training experiences are tailored to see the reform in action, the effect of that experience increases.

No association has been found between teachers’ cognitive appraisals and their social contact with persons with SEN (Beamer & Yun, 2014; Rakap et al., 2017). Contact with people with SEN may need to be more specific to classroom spaces and may need to reflect the full range of SEN behaviors to impact cognitive appraisals. The point in teachers’ careers (preservice or in-service) did not relate to the effect of interventions on boosts in cognitive appraisals. Preservice teachers often have opportunities to observe mentor teachers. However, schools are not typically structured to allow in-service teachers to observe other in-service teachers. The findings here suggest the benefit of such practices.

Longer Interventions Are Not Necessarily Better

Interventions used in the studies in this meta-analysis ranged from 5 h to 2 years. Compared to earlier findings, which indicated that the effectiveness of teacher intervention increased with its length (Guskey & Yoon, 2009; Iancu et al., 2018), the intervention effects in this meta-analysis did not vary as a function of length. A meta-analysis by Basma and Savage (2018) on the effectiveness of professional development showed that training was more effective when it lasted fewer than 30 h. Hence, there is probably more to an effective intervention than its length.

Implications for Future Research

The findings on teachers’ beliefs about inclusive education have several implications.

A Broad Perspective on Teachers’ Inclusive Belief Systems

Given the importance that teacher beliefs can have on teachers’ well-being, classroom behavior, and eventually, their students’ performance and motivation (Kiely et al., 2015), the results emphasize the need to support teachers who will be teaching in inclusive classrooms. Specifically, work can be done to help teachers reflect on their beliefs about inclusive education, feel less concerned and more optimistic about the implementation of inclusive education, and feel more capable to support students with SEN (see also Sharma et al., 2008). Here, Gregoire’s (2003) cognitive-affective approach to investigate changes in teachers’ beliefs applies well to studying teachers’ beliefs about inclusive education because teacher interventions do not necessarily affect all the different parts of the belief system in the same way. For example, Forlin and Chambers (2011) found that preservice teachers were more confident about teaching students with special needs after a course on inclusive education, but in some cases, their concerns increased, too. Only by disentangling these different parts of the belief system, we can understand the mechanisms of intervention effects and teachers’ belief change.

Future research could produce more precise results about teachers’ resources and needs when assessing teachers’ belief systems in a broad way by also including emotional appraisals and self-efficacy beliefs in addition to teachers’ cognitive appraisals of inclusive education. Disentangling teachers’ belief systems with regard to inclusive education can help support teachers in ways that are tailored to their current belief systems. Assessing all three parts of teachers’ belief systems can provide baseline information to teacher educators so that they can adapt training in ways that build upon the prior knowledge of teachers (Sharma et al., 2008) and are tailored to their needs (Kiel et al., 2020).

Assessing Teachers’ Perceived Resources

Whether teachers appraise inclusion as a challenge or threat not only depends on their belief system but also on their perceived resources, such as prior knowledge, time, or support at their school (Gregoire, 2003). In most studies in this meta-analysis, these variables were not assessed. Some research studies prior knowledge and indicates that preservice as well as in-service teachers have shallow understanding and hold misconceptions about inclusive education (Hodkinson, 2005). Evidence has been inconclusive: whereas in-service teachers’ knowledge is associated with their teaching self-efficacy (Lauermann & König, 2016), no relation was found for preservice teachers (Depaepe & König, 2018). More research is needed to understand how teachers’ beliefs and their knowledge of inclusive education are related (Forlin & Chambers, 2011). To examine where teachers need further support, it will be helpful to gather information about teachers’ perceived resources in addition to their self-efficacy beliefs, as both will affect whether they appraise the situation as challenging or threatening.