Abstract

Introduction

Previous evidence demonstrated that patients with schizophrenia consumed substantial healthcare resources in an integrated healthcare system. This study evaluated the impact of initiating once-monthly paliperidone palmitate (PP1M) on healthcare resource utilization (HRU) among patients with schizophrenia treated in a US integrated healthcare system.

Methods

This retrospective study used electronic medical records from Atrium Health. Adults with at least two diagnoses of schizophrenia who received an initial PP1M dose between September 2009 and April 2019 (the corresponding date defined the index date) and at least one subsequent dose within 90 days were included. Additionally, patients were required to have received active care (at least one healthcare visit every 6 months) during 12-month pre- and post-index periods and at least one oral antipsychotic prescription during the 12-month pre-index period. Inpatient, emergency room (ER), and outpatient visits were compared over 12-month pre- versus post-index periods within the same cohort using McNemar’s and Wilcoxon signed rank tests. Findings were reported for all patients and separately in patients with at least one schizophrenia relapse (schizophrenia-related inpatient or ER visit) during the 12-month pre-index period.

Results

The study cohort included 210 patients (mean age 34.2 years, 69.5% male, 39.1% had Medicaid). From the 12-month pre- to post-index period, the proportion of patients with visits and mean number of visits reduced for all-cause inpatient (67.6% to 22.4%, 1.2 to 0.4), 30-day readmission (12.4% to 2.4%, 0.2 to 0.1), and ER (68.6% to 45.7%, 2.3 to 1.2) visits, whereas the mean number of outpatient visits increased (8.7 to 11.6) (all P < 0.05). Similar trends were observed for mental health- and schizophrenia-related HRU. The trends in HRU in patients with prior relapse were similar with a higher extent of reduction in inpatient and ER use compared to the overall cohort.

Conclusion

Initiation of PP1M was associated with reduced acute HRU in patients with schizophrenia, indicating potential clinical and economic benefits, especially in patients with prior relapse.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics, which have reduced frequency of administration compared to oral antipsychotics, are expected to improve adherence, a common challenge in patients with schizophrenia. |

Once-monthly paliperidone palmitate (PP1M) is a commonly used LAI antipsychotic in patients with schizophrenia. |

Prior studies examining the real-world health impact of PP1M included specific patient populations (e.g., patients with certain types of health insurance such as Medicaid or Medicare Advantage or Veterans Affairs beneficiaries) and therefore had limited generalizability. |

This study examined the impact of PP1M on healthcare utilization among patients with schizophrenia treated in an integrated healthcare system in the USA. |

What was learned from this study? |

Acute healthcare utilization (inpatient and emergency room visits and readmissions) during 12 months after PP1M initiation reduced significantly compared to 12 months before PP1M initiation, indicating the potential clinical and economic benefits of PP1M. |

The findings of this study involving patients with different types of insurances and those without insurance complement the findings from previous studies on this topic conducted in specific settings and contribute to the holistic picture of the real-world health impact of PP1M. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13573862.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a serious chronic neurodegenerative mental disorder that is characterized by distortion in thoughts, perception, behavior, and speech [1, 2]. The condition is associated with positive or negative symptoms. Positive symptoms of schizophrenia may include hallucinations, delusions, and disorganized speech and behaviors, and negative symptoms may include reduced affect, inability to feel pleasure, lack of motivation, and lack of speech [1, 3]. Schizophrenia is one of the top 15 reasons for disability worldwide, affecting around 1.1% of the adult population in the USA [4, 5]. The average life expectancy of patients with schizophrenia is shorter by 15–25 years compared to those without schizophrenia [6]. The reduced life expectancy is mainly due to comorbid conditions such as cardiovascular diseases, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and substance use disorders, which are common in patients with schizophrenia [7]. Schizophrenia is associated with a significant social and economic burden. It has been reported that total annual costs attributable to schizophrenia are US $155.7 billion including US $9.3 billion direct medical costs and US $117.3 billion indirect costs (e.g., unemployment and productivity loss due to caregiving) [8]. However, despite the substantial costs associated with schizophrenia, this chronic disease does not receive the same amount of attention that is given to other chronic diseases.

Antipsychotic medications are a crucial aspect of schizophrenia treatment. Generally, lifelong treatment with antipsychotics is required to avoid symptom relapse in patients with schizophrenia. Second-generation antipsychotics such as paliperidone, quetiapine, and risperidone are used more commonly than first-generation antipsychotics such as chlorpromazine, fluphenazine, and haloperidol [9]. Adherence to antipsychotics is crucial in patients with schizophrenia and has been recognized as a national quality measure [10]. In clinical practice, adherence to oral antipsychotics has been reported to be a challenge in patients with schizophrenia, with reported non-adherence rates of over 50% [11, 12]. Non-adherence to antipsychotics is associated with an increased risk of symptom relapses, hospitalizations, and emergency room (ER) visits and higher healthcare costs [13, 14]. It has been reported that patients who discontinue antipsychotic treatment are three times more likely to experience a symptom relapse within 1 year compared to those who continue their treatment [15, 16]. A multisite prospective study examining the impact of medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia found that medication nonadherence was associated with 55% higher odds of being hospitalized, 49% higher odds of having an ER visit, and 122% higher odds of being arrested [17]. Medication nonadherence is responsible for more than US $1 billion hospitalization costs annually in patients with schizophrenia in the USA [18]. Long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics, despite having similar clinical efficacy as oral antipsychotics [19], are expected to have superior real-world effectiveness primarily due to better adherence because of reduced frequency of administration. Newly released guidelines from the American Psychiatric Association recommend LAIs as an alternative therapy to oral antipsychotics in patients with a history of poor or uncertain adherence, and/or when patients are transitioning between inpatient and outpatient settings [20]. Other guidelines recommend second-generation LAIs as an initial treatment option for patients with schizophrenia, after sufficient efficacy and tolerability has been established with the oral formulation of the same antipsychotic agent [21, 22].

Once-monthly paliperidone palmitate (PP1M), a long-acting injectable dosage form of paliperidone, was approved by the US Food Drug Administration in September 2009 for emergent and maintenance treatment of schizophrenia. Prior studies have shown that use of PP1M was associated with increased medication adherence and reduced inpatient visits, 30-day readmissions, length of stay, and ER visits [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. These studies have involved patients with certain types of insurance such as Medicaid and Medicare Advantage or specific patient populations such as Veteran Affairs patients. Scant research has been conducted from the perspective of an integrated healthcare system, which includes patients with different types of insurances and those without insurance. An integrated healthcare system involves collaborative and coordinated care provided by a commonly owned network of healthcare providers such as physicians, hospitals, and urgent care clinics [32]. There are currently more than 600 integrated healthcare systems in the USA [33]. As a result of the emphasis on care continuity and commonly adopted standards of care, the integrated healthcare system model has been associated with increased quality of care compared to fragmented healthcare settings [34]. Previous analyses revealed that patients with schizophrenia treated within a US integrated healthcare system had low rates of routine/follow-up care visits and high rates of acute healthcare visits, indicating a need to re-evaluate health management strategies and improve treatment outcomes [35]. We conducted a retrospective mirror-image study among patients with schizophrenia treated in an integrated healthcare system in the USA who were initiated on PP1M after previously being on oral antipsychotic therapy. Healthcare resource utilization (HRU) during the 12 months after PP1M initiation was compared to HRU during the 12 months before PP1M initiation.

Methods

Data Source

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using data from Atrium Health’s electronic medical records (EMRs) from January 2008 to April 2020. Atrium Health is a large integrated healthcare system located in the southeastern USA. There are over 900 care locations within the system including hospitals, physician practices, urgent care centers, surgery centers, rehabilitation facilities, home health centers, and nursing homes in the states of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. A common EMR system is used for all the facilities and data on over 10 million patient visits annually is captured within the EMR data warehouse. The EMR data warehouse contains data on sociodemographics including age, race/ethnicity, gender, and health insurance status; details regarding healthcare visits such as admission and discharge time-stamps and the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth/Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM) diagnosis and procedure codes associated with the visit; results of laboratory tests; medication orders including dose, prescribing physician; and administration of injectable medications.

Study Protocol Approval

The study protocol was approved by Advarra Institutional Review Board (Reference Number Pro00034063). This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments.

Study Population

The study cohort consisted of patients who received an administration of PP1M from September 2009 to April 2019 followed by at least one additional administration of PP1M within 90 days, with the earlier administration date defined as the index date. Eligible patients were aged 18 years or more on the index date and had at least two healthcare visits with an ICD-9/10-CM code for schizophrenia (295.XX, F20.XX, or F21) during the study period (January 2008 to 12 months after the index date), with at least one of these visits occurring prior to the index date. Patients were also required to have received active care, defined as having at least one all-cause healthcare visit every 6 months within the system, during 12 months prior to (baseline period) and 12 months after (follow-up period) the index date, and at least one prescription for an oral antipsychotic medication during the baseline period. Patients with an administration of any other LAI prior to the index date, those with a prescription for clozapine during the baseline or follow-up period, and those with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder at any time during the study period (January 2008 to the end of the follow-up period) were excluded.

The analyses were repeated in a subgroup of patients with prior schizophrenia relapse. Patients included in this subgroup analysis, additionally, had at least one schizophrenia relapse at baseline, defined as a schizophrenia-related (with an associated ICD-9/10-CM diagnosis code for schizophrenia) hospitalization or ER visit.

Measures

Demographics (age, gender, and race/ethnicity), health insurance, and comorbidities were assessed during the baseline period. Age on the index date was reported as a continuous variable. Health insurance was determined considering the patient’s payer for their healthcare visit on the index date. Comorbidities were determined on the basis of ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes associated with the patients’ healthcare visits during the baseline period. The number and proportion of patients with diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, cardiovascular conditions, respiratory conditions, neurological conditions, musculoskeletal conditions, and other mental health comorbidities (common comorbidities observed in patients with schizophrenia) were reported. In terms of mental health comorbidities, the number and proportion of patients with a cognitive disorder (dementia, delirium, or amnesia), a psychotic disorder other than schizophrenia (delusional disorder or acute or transient psychotic disorder), an affective disorder (depression or bipolar and related disorder), anxiety, stress-related or somatoform disorder, a mental disorder associated with physical or physiological disturbances, a substance use disorder, a developmental disorder or a disorder diagnosed in childhood, and an unspecified disorder were reported (see Appendix 1 in the supplementary material). Also, the Elixhauser comorbidity index (ECI) was reported on the basis of the ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes associated with the patients’ healthcare visits during the baseline period.

All-cause, mental health-related (with an associated ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM diagnosis code for a mental health condition, Appendix 1 in the supplementary material), and schizophrenia-related inpatient, 7- and 30-day readmissions, ER, and outpatient visits were compared within the same cohort during the 12-month pre- and post-index periods. The proportion of patients with each type of visit and the mean number of visits were compared.

Data Analytic Procedures

Means, medians, interquartile ranges, and standard deviations were reported for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages were reported for categorical variables. Findings were reported for the overall study cohort and separately for the subgroup with prior relapse at baseline. Comparisons of HRU measures during the 12-month pre- and post-index periods were performed using McNemar’s and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

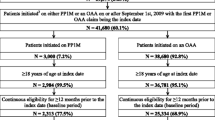

Figure 1 presents the number of patients satisfying the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The overall study cohort consisted of 210 patients. Of the total, 69.5% were male, 73.8% were black, and 39.1% had Medicaid. The mean age of the cohort was 34.2 (± 13.5) years and the mean ECI was 2.5 (± 1.6). All patients had at least one other mental comorbidity. Anxiety, stress-related, and somatoform disorders (95.2%), substance use disorders (68.1%), and psychotic disorders other than schizophrenia (61.9%) were the most common comorbid mental illnesses with 89.5% of the patients having more than one comorbid mental illness. Musculoskeletal conditions (29.5%), hypertension (28.6%), and hyperlipidemia (25.7%) were among the most common physical comorbidities (Table 1).

Of the 210 patients included in the overall study cohort, 157 (74.8%) had at least one relapse during the baseline period. Of these, 70.7% were male, 73.9% were black, and 41.4% had Medicaid. The mean age of the cohort was 33.6 (± 13.1) years and the mean ECI was 2.6 (± 1.6). Similar to the overall cohort, all patients had at least one other mental comorbidity and 91.8% had more than one. The most common mental and physical comorbidities were comparable with the overall cohort (Table 1).

HRU During 12-Month Pre- Vs. Post-Index Periods

All-Cause HRU

In the overall study cohort, from the pre- to post-index period, the proportion of patients with visits significantly decreased for all-cause inpatient visits (67.6% to 22.4%, P < 0.001), 7-day readmissions (5.2% to 1.0%, P = 0.013), 30-day readmissions (12.4% to 2.4%, P < 0.001), and ER visits (68.6% to 45.7%, P < 0.001). The mean number of visits reduced for inpatient visits (1.2 ± 1.2 to 0.4 ± 1.0, P < 0.001), 7-day readmissions (0.1 ± 0.3 to 0.0 ± 0.1, P = 0.02), 30-day readmissions (0.2 ± 0.5 to 0.1 ± 0.5, P = 0.002), and ER visits (2.3 ± 3.2 to 1.2 ± 2.3, P < 0.001) and the mean length of inpatient stay also reduced significantly (14.2 ± 16.8 to 4.4 ± 13.2 days, P < 0.001) from the pre- to post-index period. The mean number of all-cause outpatient visits increased (8.7 ± 5.5 to 11.6 ± 6.6, P < 0.001) from the pre- to post-index period (Table 2).

In the subgroup of patients with prior relapse at baseline, from the pre- to post-index period, the proportion of patients with visits significantly decreased for all-cause inpatient visits (83.4% to 25.5%, P < 0.001), 7-day readmissions (7.0% to 0.6%, P = 0.004), 30-day readmissions (15.9% to 1.9%, P < 0.001), and ER visits (80.3% to 50.3%, P < 0.001). The mean number of visits reduced for inpatient visits (1.5 ± 1.2 to 0.5 ± 1.1, P < 0.001), 7-day readmissions (0.1 ± 0.3 to 0.0 ± 0.1, P = 0.02), 30-day readmissions (0.2 ± 0.6 to 0.1 ± 0.5, P = 0.002), and ER visits (2.8 ± 3.5 to 1.4 ± 2.5, P < 0.001), and the mean length of inpatient stay also reduced significantly (17.7 ± 16.6 to 5.3 ± 14.6 days, P < 0.001) from the pre- to post-index period. The mean number of all-cause outpatient visits increased (8.2 ± 5.2 to 10.8 ± 6.1, P < 0.001) from the pre- to post-index period (Table 3).

Mental Health-Related HRU

In the overall study cohort, from the pre- to post-index period, the proportion of patients with visits significantly decreased for mental health-related inpatient visits (67.6% to 22.4%, P < 0.001), 7-day readmissions (5.2% to 1.0%, P = 0.013), 30-day readmissions (12.4% to 2.4%, P < 0.001), and ER visits (57.6% to 33.3%, P < 0.001). The mean number of visits reduced for inpatient visits (1.2 ± 1.2 to 0.4 ± 1.0, P < 0.001), 7-day readmissions (0.1 ± 0.3 to 0.0 ± 0.1, P = 0.02), 30-day readmissions (0.2 ± 0.5 to 0.1 ± 0.5, P = 0.002), and ER visits (1.5 ± 2.2 to 0.7 ± 1.4, P < 0.001) and the mean length of inpatient stay also reduced significantly (14.2 ± 16.8 to 4.4 ± 13.2 days, P < 0.001) from the pre- to post-index period. The mean number of mental health-related outpatient visits increased (6.8 ± 4.6 to 10.6 ± 5.9, P < 0.001) from the pre- to post-index period (Table 2).

In the subgroup of patients with prior relapse at baseline, from the pre- to post-index period, the proportion of patients with visits significantly decreased for mental health-related inpatient visits (83.4% to 25.5%, P < 0.001), 7-day readmissions (7.0% to 0.6%, P = 0.004), 30-day readmissions (15.9% to 1.9%, P < 0.001), and ER visits (72.6% to 35.7%, P < 0.001). The mean number of visits reduced for inpatient visits (1.5 ± 1.2 to 0.5 ± 1.1, P < 0.001), 7-day readmissions (0.1 ± 0.3 to 0.0 ± 0.1, P = 0.02), 30-day readmissions (0.2 ± 0.6 to 0.1 ± 0.5, P = 0.002), and ER visits (2.0 ± 2.4 to 0.8 ± 1.6, P < 0.001), and the mean length of inpatient stay also reduced significantly (17.7 ± 16.6 to 5.3 ± 14.6 days, P < 0.001) from the pre- to post-index period. The mean number of mental health-related outpatient visits increased (6.3 ± 4.2 to 9.8 ± 5.2, P < 0.001) from the pre- to post-index period (Table 3).

Schizophrenia-Related HRU

In the overall study cohort, from the pre- to post-index period, the proportion of patients with visits significantly decreased for schizophrenia-related inpatient visits (61.4% to 20.5%, P < 0.001), 30-day readmissions (8.6% to 1.4%, P = 0.001), and ER visits (41.9% to 27.6%, P = 0.001). The mean number of visits reduced for inpatient visits (0.9 ± 0.9 to 0.3 ± 0.8, P < 0.001), 30-day readmissions (0.1 ± 0.3 to 0.0 ± 0.3, P = 0.01), and ER visits (0.9 ± 1.5 to 0.5 ± 1.1, P < 0.001), and the mean length of inpatient stay also reduced significantly (11.9 ± 14.9 to 3.5 ± 10.5 days, P < 0.001) from the pre- to post-index period. The mean number of schizophrenia-related outpatient visits increased (4.6 ± 3.9 to 8.4 ± 5.3, P < 0.001) from the pre- to post-index period (Table 2).

In the subgroup of patients with prior relapse at baseline, from the pre- to post-index period, the proportion of patients with visits significantly decreased for schizophrenia-related inpatient visits (82.2% to 24.2%, P < 0.001), 7-day readmissions (5.1% to 0.6%, P = 0.009), 30-day readmissions (11.5% to 1.3%, P < 0.001), and ER visits (56.1% to 30.6%, P < 0.001). The mean number of visits reduced for inpatient visits (1.2 ± 0.9 to 0.4 ± 0.9, P < 0.001), 7-day readmissions (0.1 ± 0.2 to 0.0 ± 0.1, P = 0.039), 30-day readmissions (0.1 ± 0.3 to 0.0 ± 0.4, P < 0.001), and ER visits (1.2 ± 1.6 to 0.6 ± 1.2, P < 0.001), and the mean length of inpatient stay also reduced significantly (16.0 ± 15.2 to 4.5 ± 12.0 days, P < 0.001) from the pre- to post-index period. The mean number of schizophrenia-related outpatient visits increased (4.4 ± 3.7 to 8.3 ± 5.2, P < 0.001) from the pre- to post-index period (Table 3).

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study examined the HRU during 12 months before and after the initiation of PP1M in patients with schizophrenia receiving care at an integrated healthcare system in the USA. In terms of characteristics of the study cohort, similar to previous reports [36, 37], the majority of the patients initiated on PP1M were male and non-Hispanic black, possibly because of the higher risk of antipsychotic non-adherence in these patients [13, 38]. The results showed that initiation of PP1M was associated with a reduction in acute HRU (inpatient and ER use) in the overall study cohort as well as the subset of patients with prior relapse. The reduction in acute HRU after PP1M initiation is likely to be due to better control of schizophrenia symptoms associated with improvement in medication adherence compared to previous treatment with oral antipsychotics. In addition to reduction in schizophrenia-related psychotic events requiring an ER visit and/or hospitalization, better control of schizophrenia symptoms also likely positively impacts self-management behaviors with regard to physical and mental comorbidities common in these patients, thereby leading to improvement in overall physical and mental health and, in turn, reduction in mental health-related and all-cause acute healthcare use [39]. Our findings are consistent with previous similar studies on this topic [29,30,31]. For example, in a previous study of Veteran Affairs patients transitioning from orally administered paliperidone/risperidone to PP1M, Patel et al. found that the mean number of visits reduced for all-cause (2.3 to 1.5, p < 0.05), mental health-related (1.5 to 0.8, p < 0.05), and schizophrenia-related inpatient visits (0.6 to 0.3, p < 0.05) from 12 months before to 12 months after transitioning to PP1M. The mean length of stay also reduced for all-cause (28.1 to 14.0 days, p < 0.05), mental health-related (27.1 to 13.8 days, p < 0.05), and schizophrenia-related (13.2 to 5.7 days, p < 0.05) inpatient visits [30]. Other studies have compared HRU between patients on PP1M and those on oral antipsychotics and have reported reduced acute HRU in patients on PP1M compared to those on oral antipsychotics [23,24,25,26,27,28]. Manjelievskaia et al. studied multistate Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia and found lower proportions of patients with all-cause inpatient visits (25.6% vs. 33.9%, p < 0.001) and ER visits (54.7% vs. 65.8%, p < 0.001) during the 12 months after initiation of PP1M compared to patients initiated on oral antipsychotics [27].

As expected and consistent with the previous studies [24, 30], the mean number of outpatient visits increased significantly from pre to post PP1M initiation. PP1M treatment necessitates a physician outpatient visit each month as opposed to oral antipsychotic treatment in which routine visits are usually spaced every 3–6 months. The increase in the frequency of outpatient visits along with PP1M administration costs adds to the routine schizophrenia treatment costs in patients with PP1M. However, it has been reported that the increase in routine schizophrenia treatment costs in patients on PP1M is offset by the reduction in total costs due to reduced acute care utilization [23, 29, 31]. Taken together, our findings combined with those from other similar studies indicate that clinical and economic benefits are associated with PP1M.

The extent of reduction in the rates of acute HRU after PP1M initiation was higher in the subgroup of patients with prior schizophrenia relapse during the baseline period compared to the overall study cohort. For example, the proportion of patients with schizophrenia-related 30-day readmissions reduced nearly 89% from the pre- to post-index period, from 11.5% to 1.3%, in patients with prior relapse compared to about an 83% reduction from 8.6% to 1.4% in the overall cohort. The mean number of mental health-related ER visits decreased 60% from the pre- to post-index period, from 2.0 to 0.8, in patients with prior relapse compared to an approximately 53% reduction from 1.5 to 0.7 in the overall cohort. While the direct comparison of the findings between patients with and without a relapse was beyond the scope of this study, the higher relative reduction in acute HRU after PP1M initiation in patients with a relapse during the baseline period suggests that the use of PP1M could be particularly beneficial in patients with a recent relapse, who are likely to be highly non-adherent to their oral antipsychotic regimen.

Despite the likely clinical and economic benefits, the use of PP1M and other LAIs remains low in patients with schizophrenia with prescription rates less than 20% [40]. In a multisite nationwide observational study conducted in the USA, only about 12% of the patients who were non-adherent on oral antipsychotics were prescribed an LAI [41]. Patient factors such as feeling of coerciveness and/or stigma, high cost, and inconvenience due to the need to travel to the clinician’s office; physician factors such as limited knowledge and experience with LAIs, personal bias against the use of needles, and increase in workload associated with the start of a new treatment; and health system factors such as requirement of prior authorization from payors and the need for large amount of resources (budget, storage, and staff) have been reported to be the barriers to LAI use [42,43,44,45]. Some of the proposed solutions to overcome these barriers include introduction of LAIs early in the treatment course, psychological interventions to address the fear of needles, shared decision-making approach with provision of accurate and updated information to the patients, provision of better education regarding LAIs during training and residency, and easier access from the insurance companies [43,44,45]. These approaches should be implemented in routine clinical practice to increase the use of PP1M and other LAIs in appropriate patients.

There are a few limitations in this study. Data entry errors are possible in the EMRs and hence there could be inaccuracies. Prior use of oral antipsychotics was determined on the basis of prescription orders written by the physicians, not on the actual use of the medication. Also, while the inclusion criterion of one healthcare visit within the system every 6 months during the study period maximized the likelihood that patients were not lost to follow-up, it is possible that some patients completed some but not all visits within the system. Mirror-image studies are prone to expectation bias, which occurs as a result of patients’/providers’ expectations of a certain outcome when a new treatment is started [46]. Comparative analyses involving a control group of patients on oral antipsychotics were not conducted because of the difficulty in identifying a control group comparable in characteristics. Prior analyses conducted by some of the authors of the study suggested that patients initiated on PP1M usually have more severe schizophrenia and are usually less adherent to their oral antipsychotic regimen prior to PP1M initiation compared to patients who stay on oral antipsychotics. Also, imbalance between the groups is possible because of differences in factors such as family and social support, neighborhood disadvantage, employment, and lifestyle behaviors including exercise, diet, smoking, and alcohol use, information regarding which is not available in the EMRs. Therefore, a pre–post one-group study design, in which patients act as their own controls, was deemed appropriate for this study. A limitation of this study design is that it does not account for variation in patient characteristics over time. However, it could be expected that major changes in patient characteristics would not have occurred during the observation period of 24 months in this study. The impact of antipsychotic polypharmacy prior to and during PP1M use on the study outcomes was not examined as part of this study. Data on important outcomes in patients with schizophrenia such as symptom severity, cognition, quality of life, and treatment-emergent adverse events were not available. Finally, the findings of this study were from one healthcare system in the southeastern USA, primarily North Carolina, and therefore the findings may not be generalizable to other settings.

Conclusions

Initiation of PP1M was associated with reduced acute healthcare use in patients with schizophrenia receiving care at an integrated healthcare system, indicating possible clinical and economic benefits of the medication. A more substantial reduction in acute HRU was observed in patients with a prior relapse compared with the overall cohort. Initiation of PP1M may be particularly beneficial in these patients. Our findings complement the findings from previous studies using data from certain payers and/or specific healthcare settings. Strategies aimed at removing barriers to use of LAIs like PP1M in eligible patients should be implemented in clinical practice. Future studies could examine treatment continuity and health outcomes in patients initiated on PP1M transitioning between settings (e.g., post-discharge) or during unexpected events (e.g., COVID-19).

References

American Psychiatric Association. What is schizophrenia. https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/schizophrenia/what-is-schizophrenia. Accessed 9 Nov 2020.

Austin CP, Ky B, Ma L, Morris JA, Shughrue PJ. Expression of disrupted-in-schizophrenia-1, a schizophrenia-associated gene, is prominent in the mouse hippocampus throughout brain development. Neuroscience. 2004;124(1):3–10.

Foss-Feig JH, McPartland JC, Anticevic A, Wolf J. Re-conceptualizing ASD within a dimensional framework: positive, negative, and cognitive feature clusters. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(1):342–51.

Chong HY, Teoh SL, Wu DB, Kotirum S, Chiou CF, Chaiyakunapruk N. Global economic burden of schizophrenia: a systematic review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:357–73.

Lafeuille MH, Grittner AM, Fortier J, et al. Comparison of rehospitalization rates and associated costs among patients with schizophrenia receiving paliperidone palmitate or oral antipsychotics. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(5):378–89.

Wildgust HJ, Hodgson R, Beary M. The paradox of premature mortality in schizophrenia: new research questions. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(4 Suppl):9–15.

Brink M, Green A, Bojesen AB, Lamberti JS, Conwell Y, Andersen K. Excess medical comorbidity and mortality across the lifespan in schizophrenia: a nationwide Danish register study. Schizophr Res. 2019;206:347–54.

Cloutier M, Aigbogun MS, Guerin A, et al. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2013. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(6):764–71.

Van Brunt DL, Gibson PJ, Ramsey JL, Obenchain R. Outpatient use of major antipsychotic drugs in ambulatory care settings in the United States, 1997–2000. MedGenMed. 2003;5(3):16.

National Committee for Quality Assurance. Adherence to antipsychotic medications for individuals with schizophrenia (SAA). https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/adherence-to-antipsychotic-medications-for-individuals-with-schizophrenia/. Accessed 23 Oct 2020.

Valenstein M, Blow FC, Copeland LA, et al. Poor antipsychotic adherence among patients with schizophrenia: medication and patient factors. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(2):255–64.

Yaegashi H, Kirino S, Remington G, Misawa F, Takeuchi H. Adherence to oral antipsychotics measured by electronic adherence monitoring in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CNS Drugs. 2020;34(6):579–98.

Higashi K, Medic G, Littlewood KJ, Diez T, Granström O, De Hert M. Medication adherence in schizophrenia: factors influencing adherence and consequences of nonadherence, a systematic literature review. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2013;3(4):200–18.

Haddad PM, Brain C, Scott J. Nonadherence with antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia: challenges and management strategies. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2014;5:43–62.

Gilbert PL, Harris MJ, McAdams LA, Jeste DV. Neuroleptic withdrawal in schizophrenic patients. A review of the literature. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(3):173–88.

Emsley R, Chiliza B, Asmal L, Harvey BH. The nature of relapse in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:50.

Ascher-Svanum H, Faries DE, Zhu B, Ernst FR, Swartz MS, Swanson JW. Medication adherence and long-term functional outcomes in the treatment of schizophrenia in usual care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(3):453–60.

Sun SX, Liu GG, Christensen DB, Fu AZ. Review and analysis of hospitalization costs associated with antipsychotic nonadherence in the treatment of schizophrenia in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(10):2305–12.

Suzuki T. A further consideration on long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: a narrative review and critical appraisal. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2016;13(2):253–64.

American Psychiatric Association. The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Third edition. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890424841.Schizophrenia02. Accessed 9 Nov 2020.

Florida Medicaid Drug Therapy Management Program for Behavioral Health. 2019–2020 treatment of adult schizophrenia. http://www.medicaidmentalhealth.org/ViewGuideline.cfm?GuidelineID=205. Accessed 9 Nov 2020.

Mental Health Clinical Advisory Group. Mental health care guide for licensed practitioners and mental health professionals. Schizophrenia. https://sharedsystems.dhsoha.state.or.us/DHSForms/Served/le7548.pdf. Accessed 9 Nov 2020.

Baser O, Xie L, Pesa J, Durkin M. Healthcare utilization and costs of Veterans Health Administration patients with schizophrenia treated with paliperidone palmitate long-acting injection or oral atypical antipsychotics. J Med Econ. 2015;18(5):357–65.

Lefebvre P, Muser E, Joshi K, et al. Impact of paliperidone palmitate versus oral atypical antipsychotics on health care resource use and costs in veterans with schizophrenia and comorbid substance abuse. Clin Ther. 2017;39(7):1380-95.e4.

Pilon D, Muser E, Lefebvre P, Kamstra R, Emond B, Joshi K. Adherence, healthcare resource utilization and Medicaid spending associated with once-monthly paliperidone palmitate versus oral atypical antipsychotic treatment among adults recently diagnosed with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):207.

Joshi K, Muser E, Xu Y, Schwab P, Datar M, Suehs B. Adherence and economic impact of paliperidone palmitate versus oral atypical antipsychotics in a Medicare population. J Comp Eff Res. 2018;7(8):723–35.

Manjelievskaia J, Amos TB, El Khoury AC, Vlahiotis A, Cole A, Juneau P. A comparison of treatment patterns, healthcare resource utilization, and costs among young adult Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia treated with paliperidone palmitate or oral atypical antipsychotics in the US. J Med Econ. 2018;21(12):1221–9.

Pilon D, Amos TB, Kamstra R, Manceur AM, El Khoury AC, Lefebvre P. Short-term rehospitalizations in young adults with schizophrenia treated with once-monthly paliperidone palmitate or oral atypical antipsychotics: a retrospective analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(1):41–9.

El Khoury A, Patel C, Huang A, Wang L, Bashyal R. Transitioning from oral risperidone or paliperidone to once-monthly paliperidone palmitate: a real-world analysis among Veterans Health Administration patients with schizophrenia who have had at least one prior hospitalization. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(12):2159–68.

Patel C, Emond B, Lafeuille MH, et al. Real-world analysis of switching patients with schizophrenia from oral risperidone or oral paliperidone to once-monthly paliperidone palmitate. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2020;7(1):19–29.

Patel C, Khoury AE, Huang A, Wang L, Bashyal R. Healthcare resource utilization and costs among patients with schizophrenia switching from oral risperidone/paliperidone to once-monthly paliperidone palmitate: a Veterans Health Administration claims analysis. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2020;92:100587.

Enthoven AC. Integrated delivery systems: the cure for fragmentation. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(10 Suppl):S284–90.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Snapshot of U.S. health systems, 2016. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/snapshot-of-us-health-systems-2016v2.pdf. Accessed 9 Nov 2020.

Hwang W, Chang J, Laclair M, Paz H. Effects of integrated delivery system on cost and quality. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(5):e175–84.

Tcheremissine O, Mahabaleshwarkar R, Lin D, et al. Characteristics and healthcare burden of patients with schizophrenia treated in a US integrated healthcare system. Poster presentation at the US Psych Congress 2019, San Diego, CA, October 3–6, 2019.

Aggarwal NK, Rosenheck RA, Woods SW, Sernyak MJ. Race and long-acting antipsychotic prescription at a community mental health center: a retrospective chart review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(4):513–7.

Rossi G, Frediani S, Rossi R, Rossi A. Long-acting antipsychotic drugs for the treatment of schizophrenia: use in daily practice from naturalistic observations. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:122.

Acosta FJ, Hernández JL, Pereira J, Herrera J, Rodríguez CJ. Medication adherence in schizophrenia. World J Psychiatry. 2012;2(5):74–82.

Hansen RA, Maciejewski M, Yu-Isenberg K, Farley JF. Adherence to antipsychotics and cardiometabolic medication: association with health care utilization and costs. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(9):920–8.

Kirschner M, Theodoridou A, Fusar-Poli P, Kaiser S, Jäger M. Patients’ and clinicians’ attitude towards long-acting depot antipsychotics in subjects with a first episode of psychosis. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2013;3(2):89–99.

Ascher-Svanum H, Peng X, Faries D, Montgomery W, Haddad PM. Treatment patterns and clinical characteristics prior to initiating depot typical antipsychotics for nonadherent schizophrenia patients. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9:46.

Potkin S, Bera R, Zubek D, Lau G. Patient and prescriber perspectives on long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics and analysis of in-office discussion regarding LAI treatment for schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:261.

Getzen H, Beasley M, D’Mello DA. Barriers to utilizing long-acting injectable antipsychotic medications. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2013;25(4):E1-6.

Parellada E, Bioque M. Barriers to the use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in the management of schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. 2016;30(8):689–701.

Lindenmayer JP, Glick ID, Talreja H, Underriner M. Persistent barriers to the use of long-scting injectable antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;40(4):346–9.

Miura G, Misawa F, Kawade Y, Fujii Y, Mimura M, Kishimoto T. Long-acting injectables versus oral antipsychotics: a retrospective bidirectional mirror-image study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;39(5):441–5.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This research and the Rapid Service Fee were funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Prior Presentation

This study was presented as a poster presentation at the 2020 US Psych Congress Virtual Conference, September 10–13, 2020.

Disclosures

Dee Lin, Jesse Fishman, Charmi Patel, Carmela Benson, and Kruti Joshi are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, and are stockholders of Johnson & Johnson. Oleg Tcheremissine reports direct research support from Roche, Eli Lilly, and Janssen. Rohan Mahabaleshwarkar, Todd Blair, Timothy Hetherington, Pooja Palmer, and Constance Krull have no disclosures to report. Constance Krull is currently affiliated with Eli Lilly and Company. Jesse Fishman is currently affiliated with Apellis Inc.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study protocol was approved by Advarra Institutional Review Board (Reference Number Pro00034063). This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as Atrium Health privacy policies do not allow sharing data with Atrium Health patient information in order to comply with the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahabaleshwarkar, R., Lin, D., Fishman, J. et al. The Impact of Once-Monthly Paliperidone Palmitate on Healthcare Utilization Among Patients With Schizophrenia Treated in an Integrated Healthcare System: A Retrospective Mirror-Image Study. Adv Ther 38, 1958–1974 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-021-01626-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-021-01626-9