Abstract

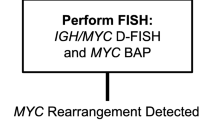

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma is a relatively rare type of T cell lymphoma characterized by strong and uniform CD30 expression with a typical cohesive growth pattern and hallmark cells. Most cases are single-positive for CD4 or less often CD8-positive, with only very rare descriptions of having double positivity for both antigens. Agent Orange is a herbicide which was used during the Vietnam War and has been associated with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (including chronic lymphocytic leukemia, hairy cell leukemia, and other chronic B cell leukemias), Hodgkin lymphoma and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Herein, we describe a unique case of anaplastic large cell lymphoma ALK-negative arising in a military veteran with documented Agent Orange exposure featuring double positivity for both CD4 and CD8 with a brief literature review that highlights the uniqueness of this rare phenotype. Our patient underwent a left neck lymph node biopsy that was worked up for a lymphoproliferative process. Based on the diagnosis rendered, a T cell lymphoma fluorescence in situ hybridization [FISH] panel was done. T cell receptor gene rearrangement studies could not be performed due to consumption of the material. A core biopsy of the left neck lymph node showed an infiltrate of frankly malignant large lymphoid cells with many featuring eccentric horseshoe/kidney shaped nuclei with an eosinophilic region near the nucleus, consistent with hallmark cells with admixed small lymphocytes, plasma cells and few neutrophils and eosinophils. The neoplastic cells were positive for CD45, CD30, CD2 [subset +], CD5, and also showed double-positive [DP] CD4 + CD8 + and were negative for CD3. FISH studies for T cell lymphoma FISH panel that included rearrangements involving ALK, TP63 and DUPS22 [IRF4] gene regions were negative. Through this case, we demonstrate a unique case of anaplastic large cell lymphoma, ALK-negative in a patient with Agent Orange exposure and featuring double positivity for CD4 and CD8.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma [ALCL] has undergone numerous definitional revisions from the earliest report by Stein et al. in 1985 which described a subgroup of tumors with large, bizarre, pleomorphic cells associated with prominent sinusoidal invasion and with expression of CD30 [1]. The current definition has evolved to be defined as a mature T cell neoplasm with uniform CD30 expression, hallmark cells, and typically a histologically cohesive growth pattern. Current World Health Organization classification further defines ALCL with ALK-negative and ALK-positive as established variants, the latter characterized by chromosomal rearrangements involving the ALK gene on 2p23. ALK [ +] ALCL represents approximately one-half of ALCL cases and is typically attributed to have superior 5-year overall survival rates of > 70%, when compared to ALCL ALK [ −] 5-year overall survival rates of < 50% [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Using these criteria, ALCL still represents a group of diseases which are heterogeneous with regard to histology, phenotype, cytogenetics, and clinical course [2, 10,11,12]. Most cases are single-positive CD4 or less often CD8 + T cells or double negative, but only isolated reports for positivity for both antigens [13,14,15]. Here, we report a rare case of ALCL, ALK-negative arising in a military veteran with documented Agent Orange exposure expressing double-positive CD4 + CD8 + and review the literature of this rare phenotype.

Clinical history and results

A 74-year-old male military veteran with past medical history significant for renal cell carcinoma requiring a left nephrectomy and with transporting and loading Agent Orange during military deployment in the Vietnam War presented with a left neck palpable nodule associated with swelling. Computed tomography [CT] revealed isolated bulky bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy. A positron emission tomography [PET-CT] revealed the abnormal FDG uptake of numerous bilateral cervical lymph nodes [3.6 cm, max SUV 23.6, with a SUV range of 3.8–5.9] without signs of abdominopelvic or extranodal involvement (Fig. 1).

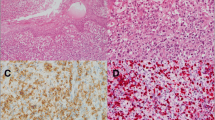

The left neck lymph node biopsy showed an infiltrate of frankly malignant large lymphoid cells with many featuring eccentric horseshoe/kidney shaped nuclei with an eosinophilic region near the nucleus, consistent with hallmark cells (Fig. 2). By immunocytochemistry the atypical lymphocytes expressed CD45, CD30, CD2[subset +], CD5 and DP CD4 + CD8 + , but negative for CD20, PAX-5, CD3, CD138, CD56, ALK-1, EMA, CD7, Granzyme-B, p63, TdT, CD1a and EBER- in-situ hybridization stains. The proliferation index estimated by Ki-67 staining was 70–80%. Fluorescence in situ hybridization [FISH] studies were negative for rearrangements involving ALK, TP63, and DUPS22 [IRF4] gene regions. A staging bone marrow biopsy showed normocellular bone marrow, with trilineage hematopoietic maturation, and no lymphoid aggregates or atypical lymphoid cells. He was diagnosed anaplastic large cell lymphoma, ALK-negative and subsequently started on 6-cycles of chemotherapy which included cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone, as well as brentuximab vedotin (BV-CHP), as the lymphoma expressed CD30. T cell receptor gene rearrangement could not be performed due to consumption of the material.

a Hematoxylin and eosin stained sections from left neck lymph node with complete architectural effacement and replacement by frankly malignant cells, some of which are hallmark cells with eccentrically placed horseshoe/kidney shaped nuclei with an eosinophilic region near the nucleus [inset] [magnification × 200]. b The neoplastic cells are positive for CD30 stain. c Negative Alk-1 staining is seen [magnification b, c: × 400]. d Positive CD4 expression by the neoplastic cells is seen [magnification × 400]. e The neoplastic cells also express CD8. [magnification × 400]

Discussion

Here we have reported a rare case of ALCL ALK-negative with immunophenotypic co-expression of both CD4 and CD8 in a military veteran with Agent Orange exposure. The incidence of DP CD4 + CD8 + T cells has been described in other lymphoproliferative diseases, particularly with T cell prolymphocytic leukemia [T-PLL] which can be seen in approximately 25% of cases [16, 17]. Other post-thymic T cell malignancies rarely coexpress these antigens [2], but some reports in the literature have shown this has potential to occur at varying low frequencies; adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma [18], angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma [14], peripheral T cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified [14]. In the context of ALCL, there is evidence that expression of either CD4 or CD8 differ biologically and are associated with unique clinical/pathologic differences. It has been reported that ALK-positive ALCL CD8-positive cases show frequent non-classical histology including small-cell/lymphohistiocytic morphology, higher relapse rate and more often requiring stem cell transplant. However, CD8 expression does not appear to impact patient overall survival or progression-free survival regardless of ALK-status [19]. The incidence of DP CD4 + CD8 + ALCL appears to be extremely rare, in fact in our literature review we were only able to identify eight cases [20,21,22]. One study, focusing exclusively on ALCL, highlights five DP CD4 + CD8 + cases with a tendency toward small cell/lymphohistiocytic morphology [4/5 cases], but individual clinical/pathologic features are not delineated further [22]. The remaining studies are summarized in Table 1, and interestingly small cell morphology also appears to be common in these cases as well [2/4 cases].

The biology of CD4 + CD8 + T cells is well described as a developmental stage within the cortical thymus, where they mature from early T cell precursors that express TdT and exhibit double negativity for both CD4 and CD8. Furthermore, the biology of these maturing T cells includes, well organized T cell antigen receptor (TCR) gene somatic rearrangements to generate a broad repertoire of TCR structures. Negative and positive selection at this stage of development results in the deletion of autoreactive thymocytes and ensures that class I and class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC) reactivity is correlated with CD8 and CD4 lineage specification [23]. To eliminate cells expressing TCRs that cannot engage self MHC molecules, DP thymocytes are subjected to strict selection pressures in which cells bearing potentially useful TCR are the only ones signaled to survive and to continue their differentiation into functionally mature T cells. The vast majority of DP thymocytes do not receive TCR survival signals and undergo ‘death by neglect’ because their TCR cannot engage self MHC molecules. This life-or-death TCR-mediated signalling event in DP thymocytes is known as ‘positive selection’ and results in the survival and maturation of cells bearing potentially useful TCRs [24]. Subsequently, these double-positive CD4 + CD8 + T cells upon leaving the thymic cortex express either CD4 or CD8 and can be found in paracortex of lymph nodes, and in the thymic medulla. Also, methylation studies reveal that ALK ( +) ALCL DNA methylation pattern resembles that of an early thymic progenitor, while ALK ( −) ALCL largely clustered with DP TCR-expressing, as well as pre-TCR T cells [25]. While it would remain unclear why a DP- phenotype in ALCL is so exceedingly rare, this does provide some evidence of a postulated cell of origin. Detection of mature CD4 + CD8 + T cells have been reported in the peripheral blood of healthy people as a small population [1–3%] [26, 27], but can be expanded in various reactive etiologies including autoimmune diseases, viral infections, and other various chronic inflammatory conditions and lymphomas including nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma [28,29,30,31,32]. The functional aspects of DP T cells are poorly understood with conflicting evidence for both a cytotoxic and/or regulatory role [25]. It is unclear, but conceivable that a lymphomatous process could derive from this biologically distinct DP T cell subset, although certainly upregulation by various mechanisms, including the neoplastic process would remain possibilities.

It is notable that the patient had been involved with transporting and loading Agent Orange during military deployment in the Vietnam War. Agent Orange was a mixture of two herbicides 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid [2,4-D], 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid [2,4,5-T], that was contaminated by TCDD [2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzine-p-dioxin] during production and used by the U.S. military during the Vietnam War in the period 1962 to 1971.

While the mechanism is not completely understood in vitro and laboratory animal models have highlighted the importance of species-specific aryl hydrocarbon receptor, which has potential to alter gene expression. Veterans and Agent Orange (VAO) committee, which was established to review the health effects of exposure to herbicides in Vietnam Veterans, currently concludes that there is sufficient evidence to support an association between prior herbicide exposure and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (including chronic lymphocytic leukemia, hairy cell leukemia and other chronic B cell leukemias), Hodgkin lymphoma and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance [33]. Of note, Lorio and colleagues report a case of cutaneous ALK( −) CD4( +)CD8( −) ALCL arising in a 68-year old man, that was accepted by the US Department of Veterans Affairs as an Agent Orange‐related lymphoproliferative disorder [34]. Additional cancers that are associated with Agent Orange exposure include soft tissue sarcoma as well as numerous with limited or only suggestive evidence (prostate, bladder, lung, laryngeal cancer etc.) [35, 36].

Of note, definitive determination of what constitutes a significant exposure to herbicides and TCDD is practically difficult given lack of reliable laboratory metrics, nor consistent data or robust tools to accurately track proximity and duration of an exposure [35].

Conclusion

In summary, we report herein a rare case of ALCL ALK [ −] with concurrent expression of both CD4 and CD8 arising in a military veteran with documented Agent Orange exposure. We emphasize that further accumulation of similar cases is warranted to clarify and elucidate any further unique clinicopathological findings.

References

Stein H, Mason DY, Gerdes J et al (1985) The expression of the Hodgkin’s disease associated antigen Ki-1 in reactive and neoplastic lymphoid tissue: evidence that Reed-Sternberg cells and histiocytic malignancies are derived from activated lymphoid cells. Blood 66(4):848–858

Campo E, Harris NL, Pileri SA et al (2017) WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. IARC Who Classification of Tum

Amin HM, Lai R (2007) Pathobiology of ALK+ anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood 110(7):2259–2267

Vose J, Armitage J, Weisenburger D (2008) International peripheral T-cell and natural killer/T-cell lymphoma study: pathology findings and clinical outcomes. J Clin Oncol 26(25):4124–4130

Pedersen MB, Hamilton-dutoit SJ, Bendix K et al (2015) Evaluation of clinical trial eligibility and prognostic indices in a population-based cohort of systemic peripheral T-cell lymphomas from the Danish Lymphoma Registry. Hematol Oncol 33(4):120–128

Gascoyne RD, Aoun P, Wu D et al (1999) Prognostic significance of anaplastic lymphoma kinase [ALK] protein expression in adults with anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Blood 93(11):3913–3921

Falini B, Pileri S, Zinzani PL et al (1999) ALK+ lymphoma: clinico-pathological findings and outcome. Blood 93(8):2697–2706

Ten Berge RL, De Bruin PC, Oudejans JJ et al (2003) ALK-negative anaplastic large-cell lymphoma demonstrates similar poor prognosis to peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified. Histopathology 43(5):462–469

Savage KJ, Harris NL, Vose JM et al (2008) ALK- anaplastic large-cell lymphoma is clinically and immunophenotypically different from both ALK+ ALCL and peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified: report from the International Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma Project. Blood 111(12):5496–5504

Kadin ME (1994) Primary Ki-1-positive anaplastic large-cell lymphoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Ann Oncol 5(Suppl 1):25–30

Tilly H, Gaulard P, Lepage E et al (1997) Primary anaplastic large-cell lymphoma in adults: clinical presentation, immunophenotype, and outcome. Blood 90(9):3727–3734

Attygalle AD, Cabeçadas J, Gaulard P et al (2014) Peripheral T-cell and NK-cell lymphomas and their mimics; taking a step forward - report on the lymphoma workshop of the XVIth meeting of the European Association for Haematopathology and the Society for Hematopathology. Histopathology 64(2):171–199

Hastrup N, Ralfkiaer E, Pallesen G (1989) Aberrant pheno- types in peripheral T cell lymphomas. J Clin Pathol 42:398–402

Went P, Agostinelli C, Gallamini A et al (2006) Marker expression in peripheral T-cell lymphoma: a proposed clinical-pathologic prognostic score. J Clin Oncol 24:2472–2479

Geissinger E, Odenwald T, Lee SS et al (2004) Nodal peripheral T-cell lymphomas and in particular, their lympho- epithelioid [Lennert’s] variant are often derived from CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells. Virchows Arch 445:334–343

Matutes E, Brito-Babapulle V, Swansbury J et al (1991) Clinical and laboratory features of 78 cases of T-prolymphocytic leukemia. Blood 78(12):3269–3274

Chen X, Cherian S (2013) Immunophenotypic characterization of T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia. Am J Clin Pathol 140(5):727–735

Kamihira S, Sohda H, Atogami S et al (1992) Phenotypic diversity and prognosis of adult T-cell leukemia. Leuk Res 16(5):435–441

Shen J, Medeiros LJ, Li S et al (2020) CD8 expression in anaplastic large cell lymphoma correlates with noncommon morphologic variants and T-cell antigen expression suggesting biological differences with CD8-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Hum Pathol 98:1–9

Medeiros LJ, Elenitoba-Johnson KSJ (2007) Anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol 127(5):707–722

Onciu M, Behm FG, Raimondi SC et al (2003) ALK-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma with leukemic peripheral blood involvement is a clinicopathologic entity with an unfavorable prognosis. Report of three cases and review of the literature. Am J Clin Pathol 120(4):617–625

Khanlari M, Li S, Miranda RN et al (2022) Small cell/lymphohistiocytic morphology is associated with peripheral blood involvement, CD8 positivity and retained T-cell antigens, but not outcome in adults with ALK+ anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Mod Pathol 35(3):412–418

Singer A, Adoro S, Park JH (2008) Lineage fate and intense debate: myths, models and mechanisms of CD4- versus CD8-lineage choice. Nat Rev Immunol 8(10):788–801. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri2416

Hassler MR, Pulverer W, Lakshminarasimhan R, Redl E, Hacker J, Garland GJ et al (2016) Insights into the pathogenesis of anaplastic large-cell lymphoma through genome-wide DNA methylation profiling. Cell Rep 17(2):596–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.018

Overgaard NH, Jung JW, Steptoe RJ, Wells JW (2015) CD4+/CD8+ double-positive T cells: more than just a developmental stage? J Leukoc Biol 97(1):31–38

Blue ML, Daley JF, Levine H, Schlossman SF (1985) Coexpression of T4 and T8 on peripheral blood T cells demonstrated by two-color fluorescence flow cytometry. J Immunol 134(4):2281–2286

Nascimbeni M, Shin EC, Chiriboga L, Kleiner DE, Rehermann B (2004) Peripheral CD4 [+] CD8 [+] T cells are differentiated effector memory cells with antiviral functions. Blood 104(2):478–486

Parel Y, Chizzolini C (2004) CD4+ CD8+ DP [DP] T cells in health and disease. Autoimmun Rev 3(3):215–220

Nascimbeni M, Pol S, Saunier B (2011) Distinct CD4+ CD8+ double-positive T cells in the blood and liver of patients during chronic hepatitis B and C. PLoS One 6(5):e20145

Zloza A, Schenkel JM, Tenorio AR, Martinson JA, Jeziorczak PM, Al-Harthi L (2009) Potent HIV-specific responses are enriched in a unique subset of CD8+ T cells that coexpresses CD4 on its surface. Blood 114(18):3841–3853

Zhao FX (2008) Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma or T-cell/histiocyte rich large B-cell lymphoma: the problem in “grey zone” lymphomas. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 1(3):300–305

Sarrabayrouse G, Corvaisier M, Ouisse LH et al (2011) Tumor-reactive CD4+ CD8αβ+ CD103+ αβT cells: a prevalent tumor-reactive T-cell subset in metastatic colorectal cancers. Int J Cancer 128(12):2923–2932

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2018) Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 11 [2018]. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press

Lorio M, Lewis B, Hoy J, Yeager M (2021) Agent orange-induced anaplastic large-cell lymphoma [Alcl] with cutaneous involvement. Clin Case Rep 9(4):2373–2381

Committee to Review the Health Effects in Vietnam Veterans of Exposure to Herbicides (Eighth Biennial Update), Institute of Medicine (2010) Veterans and Agent Orange: Health Effects of Herbicides Used in Vietnam: Update 2010. Washington, D.C.: National Academy. Print. ISBN- 13: 978- 0- 309- 21447- 6

Frumkin H (2003) Agent Orange and cancers: an overview for clinicians. Environ Carcinog 53(4):245–255

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Nicholas Ward and Nitya Prabhakaran. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Nicholas Ward and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This case report is submitted with no patient specific information. All personal identifying information has been removed. As per our institutional policies, anecdotal reports on a single patient or series of patients seen in one’s own practice and a comparison of these patients to existing reports in the literature is not research and does not require institutional review board (IRB) approval.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Prabhakaran, N., Ward, N. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma, ALK-negative exhibiting rare CD4 [ +] CD8 [ +] double-positive immunophenotype. J Hematopathol 15, 249–253 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12308-022-00517-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12308-022-00517-4