Abstract

Only few studies have investigated the link between the heterogeneity of non-democratic regime types and environmental protection. This study disaggregates authoritarian regimes and identifies four patterns of environmental performance. Using 16 indicators of environmental performance, autocratic subtypes such as royal dictatorships, military dictatorships, hegemonic autocracies, and competitive authoritarian regimes are compared and contrasted with democracies. The results demonstrate that a democracy advantage in the protection of the environment, as many former studies find it, typically cannot be confirmed for all autocratic subtypes. We rather detect a quite manifold picture when the variety of authoritarianism is taken into account.

Zusammenfassung

Nur wenige Studien haben den Zusammenhang zwischen der Heterogenität nichtdemokratischer Regimetypen und Umweltschutz untersucht. In dieser Studie werden autokratische Regime disaggregiert und vier Performanzmuster im Bereich des Umweltschutzes identifiziert. Anhand von 16 Indikatoren wird die Umweltperformanz autokratischer Regimetypen mit Demokratien verglichen. Die Ergebnisse zeigen, dass ein Demokratievorteil beim Umweltschutz typischerweise nicht für alle autokratischen Subtypen bestätigt werden kann. Unter Berücksichtigung der Heterogenität autokratischer Regime erkennen wir eher ein recht vielfältiges Bild.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

While environmental policy has played a minor role for a long time, the question of how to protect our earth has gained increasing attention from the late 1960s on, when local natural disasters as well as global issues such as acid rain and climate change became part of the political agenda (Clark et al. 2001). Today, environmental protection belongs to the most important policy fields in many countries. The relevance of environmental issues is related to the fact that the protection of the natural environment serves not only an end in itself but is, furthermore, linked to economic development (Peng et al. 2020), security (Boas and Rothe 2016), political stability (Burnell 2012), and migration (Ferris 2020). The interdependency of these challenges highlights the globality of environmental issues. Thus, attempts to protect the environment and environmental cooperation not only need to cross regional borders, but also regime boundaries.

Against the background of the high relevance of environmental issues, it is not surprising that a plethora of research has explored the conditions under which a country’s environmental performance is good or poor. Economic factors such as income and growth have been identified as major contributing factors for environmental protection, and “some economists assert that environmental quality is a simple function of income” (Binder and Neumayer 2005, p. 527). One of the most prominent findings is the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) which identifies an inverted u‑shaped relationship between wealth and pollution (Selden and Song 1994; Stern 2014; Le et al. 2016). While the significance of economic factors is without any doubt, the dominance of this research strand unjustifiably covers political factors. In fact, there is evidence for the interdependency of economic and political factors (Barrett and Graddy 2000; Whitford and Wong 2009; Fiorino 2011).

A primary concern in this regard has been the effect of regime types on environmental policy. Although there is strong support for a democracy advantage in the protection of the natural environment (Payne 1995; Neumayer 2002; Li and Reuveny 2006; Ward 2008; Kim et al. 2019), certain aspects of contemporary democracies such as corruption (Povitkina 2018), inequality (Kashwan 2017), and unresponsiveness to global issues (Eckersley 2019) challenge this advantage. Notions of environmental authoritarianism (Beeson 2010; Gilley 2012) as a conceptual counterpart to the democracy-environment nexus illustrate the complexity of the relationship between regime types and environmental protection (Burnell 2012; von Stein 2020).

Despite overall differences between democracies’ and autocracies’ environmental performance, both regime types do not form homogenous groups. Considerable heterogeneity within the respective regime types adds to the complexity concerning environmental protection (Lafferty and Meadowcroft 1997). However, the effects of within-type heterogeneity have been researched predominantly for democratic regimes (e.g. Bernauer and Koubi 2009). Only few studies address this heterogeneity for autocracies. Although the control of pollution has been found invariant across autocratic regime types (Deacon 2009), there is some evidence for differences concerning sustainability and environmental cooperativeness. Specifically, monarchies and military juntas provide lower levels of sustainability (Wurster 2011, 2013), and single-party regimes are more likely to ratify international environmental agreements than other types of autocracies (Böhmelt 2014, 2015). These results point towards different patterns of performance for different dimensions of environmental protection and certain aspects of democratic quality implemented in authoritarian regimes (Escher and Walter-Rogg 2020, von Stein 2020; c.f. section 2 for a more extensive overview).

More detailed knowledge of different autocratic subtypes’ environmental performance is crucial. This can be illustrated by the trajectory of emissions: Although only about one third of the global carbon dioxide emissions are produced in non-democratic regimes, their per capita emissions increased since 1990 much more than in democracies.Footnote 1 Adding to the aforementioned globality of environmental issues, these regimes will play a major role in the protection of the environment. In this article, we therefore investigate whether there are systematic patterns of environmental performance between subtypes of autocracy. Are specific autocratic regime types particularly worse in their environmental performance than others and, therefore, require increased attention? Do some subtypes of autocratic regimes even perform on a level with liberal democracies? We add to the existing literature on regime types and environmental protection by disaggregating the most frequent autocratic regime types based on the level of electoral competitiveness and assessing their environmental performance for a broad set of indicators. Our research links neo-institutional accounts of authoritarianism with policy research and adds to the growing body of literature on authoritarian performance profiles in the provision of public goods.

This article proceeds with a literature review on the determinants of environmental protection in section 2. In section 3, we present our data and variables. The results of our analyses are shown and discussed in section 4, before we summarize our main findings in section 5 and conclude.

2 Determinants of environmental protection

Generally, the protection of the environment “refers to the evaluation of societal attainment with relation to environmental matters” (Meadowcroft 2014, p. 28). It connects the areas of pollution (control), climate change, sustainability, and depletion of resources as well as consumption. The performance in these fields is “defined to be the results of human responses to human-induced environmental pollution problems” (Scruggs 1999, p. 11). These results include both policy output and policy outcomes (Bättig and Bernauer 2009). As this article focuses on the role of political variables, we omit a broad discussion of studies investigating the influence of economic factors on environmental protection. Rather, we critically outline theoretic arguments and empirical findings on the link between regime type and environmental protection.

2.1 Institutions and regime types

Institution-centered approaches provide theoretical arguments for both democratic environmental virtues and democracies’ inability to provide better environmental protection than autocracies. The accentuation of certain democratic qualities results in competing institutional explanations (Escher and Walter-Rogg 2020; von Stein 2020). According to Payne (1995), the core features of democracies’ environmental virtue are civil liberties, regime responsiveness, political learning, internationalism and open markets. At the same time, institutional constraints and time constraints generated by electoral terms may obstruct environmental performance in democracies. The concept of ecological democracy highlights how democracies have been unresponsive to the need for the protection of the environment (Eckersley 2019, p. 2) and, thus, democracy may not be a universal panacea for environmental protection (Povitkina 2018, p. 412). In contrast, “radical techno-fixes” (Christoff 2016, p. 10) or strong institutions in a “guided democracy” (Thompson 1995, p. 35) as well as notions of environmental authoritarianism (Beeson 2010) have attracted attention.

Empirical studies on the institutional dimension of environmental protection and regime types focus foremost on the differentiation between democratic and autocratic regimes. Concerning policy output, democracies are found to be more likely to sign multilateral environmental agreements (Congleton 1992; Fredriksson and Gaston 2000; Neumayer 2002; Leinaweaver 2012). Turning to policy outcomes, the results remain mixed. For example, some studies found democracies to be less polluted (Winslow 2005; Biswas et al. 2012; Policardo 2016) or reduce pollution faster (Farzin and Bond 2006). Others find a reversed (Midlarsky 1998; Gholipour and Farzanegan 2018; Akalin and Erdogan 2021) or null effect (Leitão 2010; Halkos and Paizanos 2013) of the regime type. Disaggregating different types of outcomes—for example soil erosion and deforestation—adds to these mixed results (Midlarsky 1998). Furthermore, there is some evidence, that the relationship between the quality of democracy and the environment is non-linear (Fiorino 2011, p. 375; von Stein 2020). These democracy effects are moderated by income level (Lv 2017; Kim et al. 2019), inequality (Torras and Boyce 1998; Kashwan 2017) and institutional stability (Buitenzorgy and Mol 2011).

The referred studies use common multidimensional indicators such as Polity or Freedom House to incorporate a countries’ democraticness. These measures aggregate a set of qualities associated with democracy into a single index. They do not cover the institutional heterogeneity within democratic or autocratic regimes and are “not sufficient to explain the performance results” (Wurster 2013, p. 89). Addressing institutional heterogeneity in democracies, the degree of consensual democracy (Scruggs 1999) and the electoral system (Fredriksson and Wollscheid 2007) do not seem to matter. However, parliamentary democracies are found to outperform presidential democracies in the provision of sustainable development (Ward 2008; Wurster 2011); the latter perform on a level with autocracies (Fredriksson and Wollscheid 2007). Recent studies highlight the importance of certain aspects of democratic quality in the provision of environmental protection. Democratic inclusiveness has been linked to better policy output, but no effects on outcomes (Böhmelt et al. 2016). The conduct of free and fair elections has been linked to better environmental outcomes, but only if citizens preferences are associated with environmental preservation (von Stein 2020).

2.2 Autocratic heterogeneity and legitimation through policy performance

Irrespective of regime type, the key motivation of any political leader is political survival (Gehlbach et al. 2016). How to achieve political survival differs between regime types based on the mode of access to and exit from power (Roller 2013; cf. section 3.1). To promote political survival, leaders cannot rely exclusively on repression (Schmidt 2012). They need to find a sweet spot between repression, cooptation and legitimation (Gerschewski 2013) and craft loyalty through redistribution (Wintrobe 2007; Dukalskis and Gerschewski 2017; Geddes et al. 2018, p. 152). Private goods (e.g., direct payments) provide individual benefits and create strong support among the beneficiaries. However, the provision of private benefits is ineffective in buying support from large groups as the cost is determined by the number of beneficiaries. In contrast, public goodsFootnote 2 provide benefits to the whole society, irrespective of their support of the regime.

In comparison to democratic leaders, autocrats systematically lack input legitimation and face a legitimacy gap (Kneuer 2012; Schmidt 2012). As a compensation, good performance in the provision of public policy can be translated into legitimacy beliefs (Morrow et al. 2008) and thus persistence (Bell 2011; Croissant and Wurster 2013; Escher and Walter-Rogg 2020). However, relying too strongly on policy performance for political survival is risky, since leaders are held accountable for their performance and failure can be penalized (Schmidt 2012; Collier and Hoeffler 2015; Ofosu 2019).

Although empirical research in this field has received growing attention over the past years, studies on the effects of autocratic heterogeneity on policies remain scattered (Roller 2013, p. 36). Notably, Croissant and Wurster (2013, p. 13) hint to systematic differences in the performance of public policies. Knutsen and Fjelde (2013) find royal dictatorships to provide better protection of property rights, and Kneuer and Harnisch (2016) as well as Stier (2017) attest them better access to modern technology. Further, one-party regimes have been found to provide comparatively low infant mortality rates (McGuire 2013). The authors link these differences to legitimation and the desire of political survival.

In the context of at least minimally competitive elections, autocratic leaders are incentivized to adapt their policy (Prichard 2018). If the leader needs the support of a larger share of the population, the policy is oriented on the median voter who typically accepts stricter environmental regulation (Escher and Walter-Rogg 2020, p. 25). Therefore, even in autocracies, elections are expected to foster accountability and distribution of environmental goods (Li and Reuveny 2006; Rydén et al. 2020). In contrast, leaders not depending on the support of larger shares of the population, may use alternative sources of legitimation, such as identity and ideology. This is, for example, the case in royal monarchies, where access to power is regulated through hereditary succession (von Soest and Grauvogel 2017).

2.3 Autocratic heterogeneity, competitiveness and time horizons

These assumptions are formalized within selectorate theory. Incentives to provide public goods are shaped by the selection institutions and the size of the group whose support is necessary to stay in power—i.e. the winning coalition (Bueno de Mesquita et al. 2003; Morrow et al. 2008). Small winning coalitions are persuaded through the provision of private benefits. In the case of larger winning coalitions, private benefits would be prohibitively expensive in comparison to the provision of public goods (Bueno de Mesquita et al. 2003, p. 101). Larger winning coalitions are naturally found in democracies. Military regimes and royal dictatorships feature systematically smaller winning coalitions. Electoral autocracies lie in-between. Based on the introduction of multi-party elections the size of their winning coalition is larger than in military regimes or monarchies (Bueno de Mesquita et al. 2003). However, depending on the actual degree of competitiveness in these regimes, the size of the winning coalition and thus the incentives to provide environmental protection differ within electoral autocracies.

In this regard, selectorate theory has been linked inter alia to regime trajectories (Aplote 2015), corruption (Chang and Golden 2010) and the provision of social services and welfare (Miller 2015; Cassani 2017; Wurster 2019). Concerning environmental protection, political competition and winning coalition size have been linked to stringency of environmental policy and lower levels of pollution (Fredriksson et al. 2005; Bernauer and Koubi 2009; Cao and Ward 2015). However, any assumption about the relationship between a regime’s competitiveness and environmental protection needs to be treated with great caution. Some studies hint to the interdependency of the size of the winning coalition with other contextual factors. For example, infant mortality is not only reduced in the presence of larger winning coalitions, but also depends on the developmental context (McGuire 2013). Furthermore, the provision of a certain policy depends on the (presumed) preferences of the selectorate. In certain contexts, both leader and the selectorate, may prefer economic development over environmental protection (Gallagher and Hanson 2015).

Furthermore, time horizons are linked to regime persistence, and they are especially relevant for environmental policy which differs from other forms of public policy due to its long-term character. Tangible results of environmental policy are oftentimes delayed from the policy implementation (Bernauer and Koubi 2009; Cao and Ward 2015; Escher and Walter-Rogg 2020; Wurster 2011). As argued for democracies (cf. section 2.1), the orientation on electoral cycles may cause preferences for immediate benefits also in electoral autocracies (Povitkina 2018) and shift costs of policy to future generations that are not part of the contemporary selectorate (von Stein 2020, p. 8; Wurster et al. 2015, p. 184). In contrast, regimes with larger time horizons are likely to implement long-term policy. Considering the irreconcilability of competitiveness and durability, the usage of a continuous regime measure is not applicable to explain environmental performance. Rather, the institutional features of regime subtypes and their systematic differences of competitiveness and durability help to make differentiated expectations concerning environmental protection.

Only few studies have addressed within-type heterogeneity of autocratic regimes empirically, and the results highlight the need of a multidimensional approach of environmental policy. As a prime example of environmental policy stringency, there are no variations between subtypes of autocracies in the control of lead content of gasoline (Deacon 2009). Furthermore, there is empiric evidence for overall higher levels of multilateral cooperativeness and presence of environmental non-governmental organizations in single-party regimes (Böhmelt 2014, 2015), and higher levels of emissions and energy consumption in monarchies (Wurster 2011, 2013). However, these approaches use regime typologies that categorize a group of heterogeneous cases as the most frequent autocratic regime type (single-party regimes or civilian dictatorships, respectively). In these regimes, the hybridity of the combination of nominally democratic institutions and authoritarian ruling creates large within-type variation based on the level of electoral competitiveness.

In sum, regimes with lower competitiveness—namely military regimes and monarchies are expected to show lower performance in the protection of environmental policy. However, the substantially larger time horizon of monarchies based on hereditary succession may outweigh the effect of the low competitiveness and enhance preferences for environmental protection. In contrast, civilian autocracies are expected to provide environmental protection depending on the actual degree of competitiveness.

2.4 Multidimensionality of environmental performance

The multidimensionality of environmental protection is usually systemized into policy output (e.g. signatories of multilateral agreements) and outcomes (e.g. emissions, cf. section 3.2). We expect a regime’s competitiveness to have a larger impact on policy output, since policy outcomes are notably affected by local and economic conditions. For example, emissions are associated with the structure of the economy whereas soil erosion or the protection of maritime biodiversity is related to location (Duit 2005).

Apart of the important distinction between policy output and outcome, subsections 2.1 to 2.3 demonstrate that findings strongly depend on the selected indicators for environmental performance. Previous literature has been dominated by studies on specific policy outcomes, such as levels of emission and pollution. The sole focus on these “headline indicators” (Meadowcroft 2014, p. 32) is criticized for neglecting the multidimensionality of environmental performance and surrounding conditions.

In contrast, studies on the policy output emphasize the commitment to the environment. Policy output may substantially affect the outcomes. For example, government expenditure on the environment as a commitment to the environment is found to explain lower levels of pollution (Duit 2005; Gholipour and Farzanegan 2018). A specific type of outputs are signatories of multilateral environmental agreements (MEA). However, signing an agreement is far removed from its ratification and actual domestic and effective policy changes (Fiorino 2011; Jahn 2016). Furthermore, some MEAs have reached global coverage providing low to no cross-national variance. Referring back to all outcome-related indicators, the implementation of environmental policies requires regulatory compliance and at least some policy stringency. If this is not the case, a single policy output might be misleading.

An alternative to single outcome-, or output-centered approaches to environmental protection are aggregated multidimensional indices, such as the Climate Change Cooperation Index (Bernauer and Böhmelt 2013), approaches towards sustainability (Ward 2008), an index of environmental policy stringency (Fredriksson and Svensson 2003), or the Environmental Performance Index (Scruggs 1999). Although these approaches allow to map out the multidimensionality of environmental protection, the weighting of the components is sometimes ambiguous, possibly shrouds inconsistent effects or is dependent on the implicit understanding of environmental performance. Further, the aggregation of single indicators is not appropriate if their effects are diametrical.

3 Data and operationalization

For our analysis we use cross-sectional data of 84 autocratic countries. To identify performance patterns, we compare these autocracies’ environmental performance with outputs and outcomes of 89 democracies. We address the multidimensionality of environmental protection by analysing 16 pertinent indicators. Furthermore, we control for economic and demographic factors.

3.1 Regime types

In order to allocate cases to several regime types, we use an updated version of the Democracy-Dictatorship dataset (DD, Cheibub et al. 2010; Bjørnskov and Rode 2018). The data first differentiates democracies and autocracies based on the presence of democratically contested electoral institutions. Therefore, it relies on a procedural minimalist conceptualization of democracy while autocracy is conceptualized through the absence of free and fair elections (Roller 2013, p. 42). Second, the autocratic regime types are classified based on the denomination of the leader into royal dictatorships, military dictatorships and civil regimes (Cheibub et al. 2010). This type of differentiation has been used in multiple analyses to assess the performance of autocracies in different fields, such as sustainability (Wurster 2010), defence spending (Blum 2021) and regime trajectories (Bennett et al. 2021).

This differentiation using denomination of the leaders is adequate for our purpose, as in autocracies the major challenge for the aforementioned desire of political survival lies within the ruling elite itself. The distinction between royal dictatorships (mainly Middle Eastern monarchies) and military dictatorships (for example Sudan and Syria) is quite common. In both regime types the autocrat needs the support of a small group of people—the royal family or caste, or the armed forces, respectively—in order to stay in power. Thus, these regimes provide low levels of competitiveness (Bueno de Mesquita et al. 2003, p. 71; Morrow et al. 2008, p. 395). Especially contemporary royal dictatorships avoid parliamentary representation and electoral contestation completely and are therefore considered least competitive (Brooker 2014, p. 51). In military regimes, the inclusion of nominally democratic institutions is possible, but it is empirically not existent (Brooker 2014, p. 253). Furthermore, the military is able to put strict constraints on electoral bodies. Therefore the actual competition for power lies outside the electoral arena (Levitsky and Way 2015, p. 35). However, the access to power is not restricted to the hereditary principle and, therefore, military regimes are more competitive than royal dictatorships.

Civilian regimes are conceptualized as a residual category, which by and large corresponds to the idea of electoral autocracy (Roller 2013, p. 42). Most civilian autocracies allow for some form of representation and conduct nominally democratic elections. Although these elections are sometimes considered a mere democratic façade, phony, or simply fraudulent, they open the arena for at least some electoral competition and oppositional activity (Diamond 2002, p. 26). Therefore, the size of the winning coalition is larger than in countries without any elections, and the autocrat needs the support of a strong party or a larger share of the population in order to stay in power.

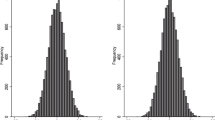

Fig. 1 illustrates main features of the regime types for the year 2017 globally. The figure importantly shows that the distinction between autocratic subtypes according to the leader is appropriate to categorize autocracies with regard to their democratic quality also empirically. Further, although the DD dataset is based on a minimalist conceptualization of democracy, its distinction between democracy and autocracy is reflected also when using alternative approaches.

In the first panel, the Combined Polity Scores are plotted grouped by the regime types. Higher scores indicating a higher degree of democratic quality. Due to their residual character, civilian autocracies comprise a large and heterogeneous group of regimes (Diamond 2002; Schedler 2013). It is therefore unsurprising that we find the largest variance for civilian autocracies, which is attributed to the combination of authoritarian governance with nominally-democratic institutions and the degree to which these institutions adhere to democratic principles. Concerning democratic quality, the regimes are differentiable on average. Turning to competitiveness operationalized using the Legislative Index of Electoral Competitiveness (LIEC) from the Database of Political Institutions (DPI), we find the regimes in the anticipated order, with royal dictatorships followed by military dictatorships having the lowest degree of competitiveness. However, civilian regimes are on average as competitive as democracies and therefore may be considered in terms of competitiveness more similar to democracies than to autocracies. Keeping their systematically lower democratic quality in mind, it is necessary to further differentiate these regimes. In competitive authoritarian regimes, there is a realistic chance of changes in power due to elections. Examples are the Russian Federation and Zambia. However, the incumbent or ruling party manages the electoral arena, therefore these chances are considerably smaller than in democracies. In contrast, regimes where the incumbent party strongly dominates the party system—like Turkmenistan and Ethiopia—are commonly considered hegemonic authoritarian regimes (Diamond 2002). Therefore, we incorporate this differentiation in the regime classification.

The basis for this differentiation is competitiveness, as this is crucial for the testing of the assumptions of selectorate theory. We classify civilian regimes into competitive authoritarian regimes and hegemonic regimes using LIEC (DPI). Countries, where only one party competed in the elections, or the winning party received more than 75% of the parliamentary seats (LIEC ≤ 6) are considered hegemonic authoritarian. Where the largest party received less than 75% of all parliamentary seats (LIEC = 7) the regime is considered competitive authoritarian (c.f. Magaloni 2006; Brownlee 2009, p. 524; Lueders and Croissant 2014, p. 336).

Lastly, Fig. 1 illustrates the presumed time horizons operationalized as the years since the last regime change (POLITY). While competitiveness and democratic quality are distributed among the regimes in a similar pattern, durability breaks this pattern. Monarchies have the longest tenure, followed by democracies. Lower tenures are found for military regimes and civilian regimes. Considering the aforementioned importance of time horizons for environmental protection, it is therefore not possible to assess the effect of regime types on these policies using a single continuous measure (e.g., competitiveness). By disaggregating the regime types, we are able to account for the opposing incentives to provide environmental protection. As the purpose of this article is to highlight the variance among autocratic regime types, we do not disaggregate democratic regimes, which will be included as a single reference category.

3.2 Environmental protection

To address the multidimensionality of environmental protection, we use a set of 16 indicators. These indicators cover policy outcomes and outputs and are systemized in four groups: multi-dimensional indexes, emissions, sustainability/development, and area related indicators. Highlighting the environmental aspect of sustainability, these 16 indicators represent both weak and strong sustainability measures. Table 1 provides an overview of this systemization and the associated indicators.Footnote 3

First, we use four multidimensional measures. The Cooperation Index (CI) measures the cooperative behaviour of states in the mitigation of climate change across countries and differentiates policy outcomes and output. CI [outcome] focusses on emissions and measures per capita CO2 relative to the GDP, and emissions trends. CI [output] rather measures commitments expressed in the ratification of multilateral agreements (UNFCCC, the Kyoto Protocol), and whether national climate reports were submitted. The time dimension is included by incorporating the time it took for ratification, and whether reports were submitted in time (Bättig et al. 2008; Bättig and Bernauer 2009). The Environmental Performance Index (EPI) is a compound of measures for environmental health and ecosystem vitality (Wendling et al. 2018). The index incorporates tangible policy outcomes, such as air quality or access to sanitation systems. These outcomes are evaluated in relation to policy targets. (Meadowcroft, 2014, p. 39). Finally, the Ecological Footprint measures the resources required to compensate the consumption of a population and is measured in global hectares per capita (Global Footprint Network 2017).

Second, we include four outcome-related indicators for emissions. Carbon dioxide (CO2), nitrous oxide (N2O), methane (CH2) and sulphur hexafluoride (SF6) are considered greenhouse gases and therefore related to the earth’s surface temperature. Aside from regime type, these emissions are also influenced by the economic structure and developmental factors. Carbon dioxide is related to energy production by the combustion of fossil fuels. Sulphur hexafluoride is used as insulation in high voltage engineering. In contrast, methane and nitrous oxide are mainly related to agriculture. Therefore, we decided not to aggregate these pollutants. All emissions are measured as metric ton per capita and in carbon dioxide equivalents (Worldbank 2019).

Third, we include measures related to sustainability and development. As large portions of the carbon dioxide emissions are related to energy production, renewable energy production provides a sustainable alternative. We use the share of the total generation of electricity, and the share of the electricity consumed that is renewable. Furthermore, we include two components of the EPI separately in this cluster. Lead exposure (PBD) measures the age-standardized disability-adjusted life years lost per 100,000 inhabitants (DALY-rate) due to exposure to lead. The variable waste water treatment (WWT) measures the percentage of the wastewater treated and weighed by the percentage of the population connected to the sewage systems. Both components are transformed relative to targets for good performance (distance-to-target method) in the respective field. These variables are operationalized as outcomes, but notably, they are more dependent on regulation through output than other types of outcomes and depend on the effective enforcement of this output and state capacity. For example, lead-caused health risks are commonly avoided through legislation and regulation on lead content in gasoline (Deacon 1999; Fredriksson et al. 2005). Similarly, the production and usage of renewable energy can be understood as a commitment to reduce emissions.

Finally, we include measures related to the area and biodiversity of a country. The variable protected land area measures the percentage of the total area of a country that is under protection and combines maritime and terrestrial protected areas (Worldbank 2019). We also include the protected area representativeness index, which measures the ecological representativeness of the area under protection. Furthermore, these areas are measured in relation to the distribution of species using the species protection index (SPI) from the EPI (Wendling et al. 2018). Lastly, we use the annual level of deforestation which reports the annual change of the area covered in forest as percentage of the total area of a country. The change measure indicates the change in percentage points (Worldbank 2019). With the exception of deforestation, these indicators are understood as a commitment to the environment and thus output-related.

Addressing the distinction between weak and strong sustainability, weak sustainability indicates substitutability between different forms of capital. In the environmental context this refers to the idea of CO2-compensation, for example. All the indicators of sustainability/development and area-related indicators fall in this group. The only exception is deforestation, which rather refers to strong sustainability. Strong sustainability assumes resources non-complementary and highlights the need for protection. In addition to deforestation, all multi-dimensional indicators and emissions fall in this group.

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive analysis

We begin our analysis by highlighting variations of environmental performance across regime types. We analyse the indicators for environmental performance based on cross-sectional data. In Online Appendix A1, the years included, and descriptive data are provided. Table 2 summarizes the results of t-tests between democracies and autocracies, and between democracies and autocratic subtypes respectively. To improve comparability, higher values represent better performance of democracies in all indicators. Accordingly, the ecological footprint, all emission related indicators, and deforestation were reversed.

Starting with differences between democracies and autocracies in general (first column), we find statistically significant differences for only half of our 16 indicators. Mainly negative t-values indicate worse performance of autocracies with the only exception of the ecological footprint. These first results carefully hint to a democracy advantage in environmental protection but also show that the evaluation strongly depends on the conceptualization and measurement.

The further columns in Table 2 demonstrate the variety of patterns when turning to autocratic subtypes. For only three out of 16 indicators the differentiation of autocratic subtypes adds no informational value. Democracies outperform both autocracies generally and each autocratic subtype with regard to CI [Output], PBD, and PAR. For three further indicators (EPI, SPI and protected area), democracies outperform all autocratic subtypes with one exception constructing an at least largely homogeneous picture. Further three measures (CH4, SF6, and deforestation) indicate no significant differences between democracies and autocracies—neither for the full sample nor for the subtypes. Although signs are changing, also these two could largely be interpreted as autocratic homogeneity.

For the remaining seven indicators, however, subtypes seem to matter. For wastewater treatment (WWT), we find a positive t-value for the comparison between royal dictatorships and democracies hinting to a better performance of the former, in contrast to all other autocratic subtypes. For the ecological footprint, the democracy-autocracy comparison is statistically significant and positive. However, this democracy disadvantage might be driven by certain subtypes only, as only two of the regime subtypes show statistically significant results and the sign changes for royal dictatorships. The remaining indicators are interesting as the simple comparison between democracies and autocracies hints to a null effect, while the view on subtypes reveals significant differences for certain regime subtypes. For Renewables [Consumption] and CO2, we even find contrary effects for different autocratic subtypes.

Taken together, we find a democracy advantage for all policy output indicators and most indicators related to weak sustainability. This is not the case for policy outcomes and strong sustainability, where the patterns are more diverse and at least carefully hint to authoritarian heterogeneity in the provision of environmental protection and highlight the importance of disaggregation of non-democratic regimes.

4.2 Regression analyses

To control for determinants of environmental protection aside from regime type we run regression analyses including a broad set of variables considered as influential in former research. These variables are the GDP and the squared GDP, GDP growth, population growth and density, the natural resource rent, corruption, climate vulnerability and regime durability. All independent variables are described in Online Appendix A1.Footnote 4

In Table 3 we provide the regression coefficients for regime types when controlling for these economic and socio-economic factors. Each column refers to one of our indicators and summarizes two regression models: in the top rows, autocracy is included as a dummy variable while the models in the bottom rows control for autocratic regime subtypes. In each case, democracies are used as reference category.

For reasons of brevity, we omit the coefficients of control variables from the regression output.Footnote 5 Overall, the control variables are barely affected by the type of regime variable included and remain fairly robust in this regard. However, there are substantial differences between the single indicator groups for environmental performance. Concerning policy output, most of our control variables remain statistically insignificant. For policy outcomes, we find natural resource rents to have largely negative effects. Climate vulnerability is only statistically significant for three indicators and has a positive effect in these cases. Similarly, corruption is significant for two indicators only and has in these cases positive effect. The effects of GDP, GDP growth, population growth, population density, and a regimes durability remain inconclusive depending of the type of dependent variable. For example, population density affects CH4 emissions positively and protected area negatively, and thus reflects the related economic and demographic implications. Not surprisingly, dense populations are less agricultural (CH4) and provide less space for area protection. The effect of the GDP is mostly negative, with the exception of the ecological footprint and CO2. These indicators are related to industrial modernization which results in larger ecological footprints and CO2 emissions. Notably, when controlling for the effect of autocracy only, we find evidence for the EKC for seven of our indicators (Ecological Footprint, CO2, SF6, Renewables [Consumption] PBD, PA, SPI). However, when controlling for autocratic subtypes, these effects diminish with the exception of the footprint and CO2.

Returning to regime types, the effects reported in Table 3 confirm the importance of institutional variables. 11 of our 16 indicators are connected with statistically significant effects for either autocracy in general or for autocratic subtypes.

Where we find general effects of autocracy—which is the case for five performance measures, most of them being outputs and related to strong sustainability—they indicate a democracy advantage. Again, this advantage is not transferable to all subtypes of autocratic regimes. For none of these measures, subtype effects are throughout statistically significant and have the same sign like autocracy’s coefficient. For EPI, PAR and SPI, one could argue that at least the coefficients’ signs remain uniform and the lacking significance could be caused by smaller case numbers. Still, at least some of the coefficients are very small and therefore the number of observations is most likely not the only explanation for differences. We see similar patterns for CO2, Renewables [Consumption] and PA with the difference that, there, even some coefficients change their sign. Admittedly, all the respective variables are insignificant and coefficients are small, so this result should not be overstated.

Vice versa, Table 3 identifies five indicators for which the sample of all autocracies suggests no significant differences to democracies, but specific subtypes seem to deviate. This is often the case for royal dictatorships which perform worse than democracies regarding indicators associated with weak sustainability (Renewables [Consumption] and PBD), but better with respect to waste water treatment. For deforestation, military dictatorships perform worse than democracies. Interestingly, two subtype dummies are statistically significant for Renewables [Output], but the coefficients’ signs differ. While democracies perform better than competitive autocracies, they are outperformed by hegemonic autocracies. Merging all autocratic subtypes, however, indicates a null effect of the regime type.

4.3 Patterns of autocratic heterogeneity

To further investigate and systematize the authoritarian heterogeneity observed in Tables 2 and 3, we illustrate the fitted values for the regression analyses in Fig. 1. By using the fitted values, we are able to account for different economic conditions and developmental levels in the respective regimes on average. Thus, this analysis of concise performance patterns considers the interplay of economic and institutional effects closely linked to the actual empiric cases. On each panel the boxplots are in order of the assumed competitiveness of the respective regime type increasing from left to right.

A visual inspection of Fig. 2 reveals four different patterns of autocratic subtypes’ influence on environmental protection. First, there are cases of little to no variation between the autocratic regime types, which is indicated by similar medians. Second, we find cases of no variance with one exception. This outlier’s performance can be better or worse than the other subtypes’. Third, we find u‑shaped patterns in which intermediate regimes perform worst, and both highly competitive and highly uncompetitive autocracies are more successful. Our fourth pattern reverses this relationship and is best described as an inverted u.

The role of democracies within these patterns is ambiguous. In some cases, democracies are imbedded in the pattern logic, and in others the u or inverted u applies only to the autocratic subtypes leaving democracies an outlier. Furthermore, these patterns are not fully disjoint. For example, Fig. 2 shows indicators with low variance between the subtypes based on the medians, while at the same time, systematic shifts of the interquartile range may hint towards heterogeneity of some type rendering overlaps in the interpretation of these patterns.

We attribute no variance to CI [Output], PBD and deforestation, although the former could be also interpreted as a flattened u and the latter two as a flattened inverted u. We detect the outlier pattern for CI [Outcome], all emission related indicators, and waste-water treatment. In all these cases royal dictatorships are the outliers being outperformed by the remaining regime types. We find u‑shaped patterns for the EPI and WWT, and a flattened version for CI [Output]. These u‑curves are not completely symmetrical allowing also interpretations of outliers (e.g. royal dictatorships for WWT). Inverted u‑shapes appear for the production and consumption of renewable energy, PBD (flattened) and all area related indicators (flattened for deforestation). These indicators highlight again the ambiguous role played by democracies. For the consumption of renewable energy, democracies are embedded within the inverted u, showing relatively low levels of consumption of renewable energy. In contrast, for PA and PAR we find the inverted u only for autocratic subtypes while democracies perform on a level with hegemonic authoritarian regimes and outperform all remaining regime types. For the SPI, we even find a clear democracy advantage.

Taken together, we find mostly for tangible outcomes associated with strong sustainability little variance with the exception of royal dictatorships. Therefore, we can confirm that there is little variance also in citizens preferences for environmental protection and the regimes responsiveness to these preferences. We attribute the different performance of outliers mostly to opposing economic preferences. For outputs and outcomes related to weak sustainability, the patterns are more mixed and emphasize the role of hegemonic authoritarianism.

4.4 Sensitivity and robustness checks

Concerning the performance of specific regime types, we find royal dictatorships and hegemonic regimes to cause a great portion of heterogeneity across our indicators. However, the small number of observations within these regimes may cause suspicion. To assess whether these identified patterns are caused by influential observations or systematically larger errors for certain regime types, we run a set of robustness and sensitivity checks.

First, we rule out systematically skewed errors by checking the distribution of standardized residuals across regime types.Footnote 6 On average, the residuals show similar levels in each regime type. This means that heteroscedasticity can be ruled out as problem for our regression models. An exception are SF6 emissions. For this indicator, the residuals of royal dictatorships vary broadly, and their median is on average larger than for the other regime types. These patterns hint to an underestimation of SF6 emissions in the regression. Therefore, the outlier position of royal dictatorships is smaller than estimated by the model. For some indicators (e.g. SPI, Renewables), we find overall larger variance of the residuals, that hint to the presence of influential observations.

We identify these influential observations using Cook’s distance. Factoring in leverage and residuals, Cook’s distance simulates the effect of the omission of observations for the regression estimates. Observations exceeding either the common threshold value of D > 1 (Cook and Weisberg 1982, p. 118) or the more strict threshold of D > \(\frac{4}{n}\) (Nieuwenhuis et al. 2012) are deemed influential. These observations are identified in Figure A2‑2 and Table A2‑1. To provide an overview, these countries are mapped in Figure A2‑3. The figure clearly illustrates the larger frequency of influential cases in countries located in the global south. Interestingly, the three observations having most frequently a large influence are Poland (9), the Philippines (5), and Kenya (5). The former two show for some models even D > 1. These observations, however, are all classified as democracies. As our research focuses on authoritarian heterogeneity and autocratic subtypes, we treated democracies as reference category. Therefore, we attribute the large influence of these cases on the broadness of electoral democratic regimes as reference category.

In a next step, we test whether the identified patterns are robust against the omission of all these influential cases. In Figure A2‑4, we compare the initial regression results of the full sample (left panel) with results omitting all influential cases (right panel). Our patterns remain largely robust.Footnote 7

5 Conclusion

The main goal of this article was to investigate performance patterns of authoritarian regimes in environmental policy. Taken together, our results show that there is no universal disadvantage of autocracies in the provision of environmental protection. Indeed, where differences between democracies and autocracies are statistically significant, democracies typically perform better than autocracies (Table 2). But when we focus on specific autocratic subtypes, their heterogeneity becomes evident. Variations in institutional settings shape the conditions under which power is preserved and thus provide variation in the way interests are shaped and enforced. When we control for economic and further factors, the picture becomes even more diverse (Table 3, Fig. 2).

Regarding policy output measures and weak sustainability, we see that often hegemonic authoritarian regimes perform on a similar level with democracies. For some indicators, hegemonic autocracies even outperform democracies. Accounting for autocratic heterogeneity, furthermore, reveals patterns in which a seemingly general democracy advantage is largely caused by a certain regime subtype. Most frequently, royal dictatorships are outliers for outcomes and strong sustainability. These results are important as they hint to potential but unapparent allies of democracies when it comes to cross-border implementation of environmental policies.

As noted in the introduction, cooperation across regime boundaries is crucial especially as we see larger per capita increases of CO2 emissions in autocracies than in democracies (Fn. 1). In fact, regarding autocratic heterogeneity, the largest increases are observable for royal dictatorships (on average 3.78 metric tons per capita), whereas the average increase for hegemonic authoritarian regimes remains below democracies (0.20 metric tons per capita). Therefore, the described performance patterns may be transferable to the development of these indicators, which is a fruitful area for further research.

In the article at hand, it was our aim to draw a comprehensive picture. We therefore analysed a broad set of indicators. The multidimensionality of the natural environment itself required a certain degree of prioritization of indicators. For reasons of feasibility and clarity we chose 16 indicators, which are also linked to previous research. We are aware that numerous further indicators could have been considered (e.g. PFC emission, CO2 emissions by its source, or government spending for environmental purposes). Future research focusing on these further indicators can help to complete this picture.

Conversely, using a broad approach did not allow us to go into detail too often so that in-depth studies can help to supplement our analyses. In particular a focus on specific regime subtypes can deepen our understanding. Importantly, the often good performance of royal and hegemonic autocracies and its structural link to durability needs to be explored in detail in future research. Beyond, our results offer considerable potential for single-country studies, most notably the influential cases which we identified in Online Appendix A2, but also the outliers visible in Fig. 2.

Finally, we would like to name three ideas for future research that our reviewers pointed out to us. First, except for deforestation, we used static indicators for our analyses which is in line with previous literature. However, environmental protection understood as a human response introduces a temporal dimension. Any type of commitment to the environment or policy will be effective only with a time lag. For this reason, we used lagged independent variables. Alternatively, value changes of the dependent variables could be used to capture improvements in the respective indicators. Furthermore, the status of the environment may not only be determined by the regime type but also affect political stability and thus the regime type itself. In this regard, regime changes may provide a quasi-experimental setting for the analysis of environmental performance. Second, regime types are not distributed equally across all regions globally. On the one hand, there are regions in which one regime type is pre-dominant. This is the case for Europe where most countries are democratic. On the other hand, some regime types occur mainly in one world region, most notably royal dictatorships which are—with the exception of Eswatini—all located in the Middle East. We accounted for regional aspects by including economic factors and climate vulnerability into the analysis. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that further regional effects interact or coincide with regime type effects. Therefore, future research is needed for in-depth studies analysing the connection between regime type and region and its effect on environmental performance. Third and in a similar context, we addressed environmental protection as a national phenomenon. Since countries are embedded in regional networks that may support or hinder environmental protection, future research should systematically address the linkage and leverage of regional and international integration.

Notes

In autocracies, per capita emissions grew on average 0.93 metric tons of carbon dioxide between 1990 and 2014. In the same period, these emissions grew on average only 0.21 metric tons per capita in democracies.

The operationalization and descriptive statistics of these indicators are summarized in the Online Appendix (Tables A1‑1 and A1-2). The number of observations within each regime type is reported in Table A1‑4.

Based on the cross-sectional character of the analyses, the independent variables are lagged one year from the dependent variables. The only exception is climate vulnerability, which is understood as a constant factor.

All coefficients are reported in Online Appendix A1 (Tables A1‑5 and A1-6).

Supporting Figures are provided in Online Appendix A2.

References

Akalin, Guray, and Sinan Erdogan. 2021. Does democracy help reduce environmental degradation? Environmental Science and Pollution Research 28:7226–7235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-11096-1.

Aplote, Thomas. 2015. Autocracy and the public: Mass revolts, winning coalitions, and policy control in dictatorships. Discussion Paper Center for Interdisciplinary Economics 5.

Barrett, Scott, and Kathryn Graddy. 2000. Freedom, growth, and the environment. Environment and Development Economics 5:433–456. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X00000267.

Bättig, Michèle B., and Thomas Bernauer. 2009. National institutions and global public goods: are democracies more cooperative in climate change policy? International Organization 63:281–308. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818309090092.

Bättig, Michèle B., Simone Brander, and Dieter M. Imboden. 2008. Measuring countries’ cooperation within the international climate change regime. Environmental Science & Policy 11:478–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2008.04.003.

Beeson, Mark. 2010. The coming of environmental authoritarianism. Environmental Politics 19:276–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644010903576918.

Bell, Curtis. 2011. Buying support and buying time: the effect of regime consolidation on public goods provision. International Studies Quarterly 55:625–646. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2011.00664.x.

Bennett, Daniel L., Christian Bjørnskov, and Stephan F. Gohmann. 2021. Coups, regime transitions, and institutional consequences. Journal of Comparative Economics 49:627–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2020.05.008.

Bernauer, Thomas, and Tobias Böhmelt. 2013. National climate policies in international comparison: the Climate Change Cooperation Index. Environmental Science & Policy 25:196–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.09.007.

Bernauer, Thomas, and Vally Koubi. 2009. Effects of political institutions on air quality. Ecological Economics 68:1355–1365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.09.003.

Binder, Seth, and Eric Neumayer. 2005. Environmental pressure group strength and air pollution: an empirical analysis. Ecological Economics 55:527–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2004.12.009.

Biswas, Amit K., Mohammad Reza Farzanegan, and Marcel Thum. 2012. Pollution, shadow economy and corruption: theory and evidence. Ecological Economics 75:114–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.01.007.

Bjørnskov, Christian, and Martin Rode. 2018. Regime types and regime change: a new dataset [v 2.2. The Review of International Organizations https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3234263.

Blum, Johannes. 2021. Democracy’s third wave and national defense spending. Public Choice 189:183–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-020-00870-x.

Boas, Ingrid, and Delf Rothe. 2016. From conflict to resilience? Explaining recent changes in climate security discourse and practice. Environmental Politics 25:613–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2016.1160479.

Böhmelt, Tobias. 2014. Political opportunity structures in dictatorships? Explaining ENGO existence in autocratic regimes. The Journal of Environment & Development 23:446–471.

Böhmelt, Tobias. 2015. Environmental interest groups and authoritarian regime diversity. Voluntas 26:315–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-013-9434-x.

Böhmelt, Tobias, Marit Böker, and Hugh Ward. 2016. Democratic inclusiveness, climate policy outputs, and climate policy outcomes. Democratization 23:1272–1291. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2015.1094059.

Brooker, Paul. 2014. Non-democratic regimes. Comparative government and politics. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Brownlee, Jason. 2009. Portents of pluralism: How hybrid regimes affect democratic transitions. American Journal of Political Science 53:515–532. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00384.x.

Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce, Alastair Smith, Randolph M. Siverson, and James D. Morrow. 2003. The logic of political survival. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Buitenzorgy, Meilanie, and Arthur P.J. Mol. 2011. Does democracy lead to a better environment? Deforestation and the democratic transition peak. Environmental and Resource Economics 48:59–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-010-9397-y.

Burnell, Peter. 2012. Democracy, democratization and climate change: complex relationships. Democratization 19:813–842. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2012.709684.

Cao, Xun, and Hugh Ward. 2015. Winning coalition size, state capacity, and time horizons: an application of modified selectorate theory to environmental public goods provision. International Studies Quarterly 59:264–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12163.

Cassani, Andrea. 2017. Social services to claim legitimacy: comparing autocracies’ performance. Contemporary Politics 23:348–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2017.1304321.

Chang, Eric, and Miriam A. Golden. 2010. Sources of corruption in authoritarian regimes. Social Science Quarterly 91:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2010.00678.x.

Cheibub, Jose Antonio, Jennifer Gandhi, and James Raymond Vreeland. 2010. Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice 143:67–101.

Christoff, Peter. 2016. Renegotiating nature in the Anthropocene: Australia’s environment movement in a time of crisis. Environmental Politics 25:1034–1057. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2016.1200253.

Clark, William C., Jill Jäger, and Josee Van Eijndhoven. 2001. Managing global Environemental change. In Learning to manage global environmental risks, Vol. 1, 1–20. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Collier, Paul, and Anke Hoeffler. 2015. Do elections matter for economic performance? Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 77:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/obes.12054.

Congleton, Roger. 1992. Political Insitutions and pollution control. The Review of Economics and Statistics 74:412–421.

Cook, R. Dennis, and Sanford Weisberg. 1982. Residuals and influence in regression. Monographs on statistics and applied probability. New York: Chapman and Hall.

Croissant, Aurel, and Stefan Wurster. 2013. Performance and persistence of autocracies in comparison: introducing issues and perspectives. Contemporary Politics 19:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2013.773199.

Deacon, Robert. 1999. The political economy of environment-development relationships: a preliminary framework. Departmental Working Papers. Department of Economics. Santa Barbara: University of California.

Deacon, Robert. 2009. Public good provision under dictatorship and democracy. Public Choice 139:241–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-008-9391-x.

Diamond, Larry. 2002. Thinking about hybrid regimes. Journal of Democracy 13:21–35. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2002.0025.

Duit, Andreas. 2005. Understanding enviromental performance of states: an institutional-centered approach and some difficulties. QOG Working Paper Series.

Dukalskis, Alexander, and Johannes Gerschewski. 2017. What autocracies say (and what citizens hear): proposing four mechanisms of autocratic legitimation. Contemporary Politics 23:251–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2017.1304320.

Eckersley, Robyn. 2019. Ecological democracy and the rise and decline of liberal democracy: looking back, looking forward. Environmental Politics https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1594536.

Escher, Romy, and Melanie Walter-Rogg. 2020. Environmental performance in democracies and autocracies: democratic qualities and environmental protection. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Farzin, Y. Hossein, and Craig A. Bond. 2006. Democracy and environmental quality. Journal of Development Economics 81:213–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2005.04.003.

Ferris, Elizabeth. 2020. Research on climate change and migration where are we and where are we going? Migration Studies 8:612–625. https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnaa028.

Fiorino, Daniel J. 2011. Explaining national environmental performance: approaches, evidence, and implications. Policy Sciences 44:367–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-011-9140-8.

Fredriksson, Per, and Noel Gaston. 2000. Ratification of the 1992 climate change convention: what determines legislative delay? Public Choice 104:345–368.

Fredriksson, Per, and Jakob Svensson. 2003. Political instability, corruption and policy formation: the case of environmental policy. Journal of Public Economics 87:1383–1405.

Fredriksson, Per G., Eric Neumayer, Richard Damania, and Scott Gates. 2005. Environmentalism, democracy, and pollution control. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 49:343–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2004.04.004.

Fredriksson, Per G., und Jim R. Wollscheid. 2007. Democratic institutions versus autocratic regimes: The case of environmental policy. Public Choice 130:381–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-006-9093-1.

Gallagher, Mary E., and Jonathan K. Hanson. 2015. Power tool or dull blade? Selectorate theory for autocracies. Annual Review of Political Science 18:367–385. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-071213-041224.

Geddes, Barbara, Joseph Wright, and Erica Frantz. 2018. How dictatorships work: power, personalization, and collapse. : Cambridge University Press.

Gehlbach, Scott, Konstantin Sonin, and Milan W. Svolik. 2016. Formal models of nondemocratic politics. Annual Review of Political Science 19:565–584. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-042114-014927.

Gerschewski, Johannes. 2013. The three pillars of stability: legitimation, repression, and co-optation in autocratic regimes. Democratization 20:13–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2013.738860.

Gholipour, Hassan F., and Mohammad Reza Farzanegan. 2018. Institutions and the effectiveness of expenditures on environmental protection: evidence from Middle Eastern countries. Constitutional Political Economy 29:20–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-017-9246-x.

Gilley, Bruce. 2012. Authoritarian environmentalism and China’s response to climate change. Environmental Politics 21:287–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2012.651904.

Global Footprint Network. 2017. NFA 2017 national footprint accounts data set (1961–2013)

Gómez-Rubio, Virgilio. 2017. ggplot2—elegant graphics for data analysis. Journal of Statistical Software https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v077.b02.

Halkos, George E., and Epameinondas Α. Paizanos. 2013. The effect of government expenditure on the environment: an empirical investigation. Ecological Economics 91:48–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.04.002.

Jahn, Detlef. 2016. The politics of environmental performance: institutions and preferences in industrialized democracies. Cambridge University Press.

Kashwan, Prakash. 2017. Inequality, democracy, and the environment: a cross-national analysis. Ecological Economics 131:139–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.08.018.

Kim, Soohyeon, Baek Jungho, and Eunnyeong Heo. 2019. A new look at the democracy-environment nexus: evidence from panel data for high- and low-income countries. Sustainability https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082353.

Kneuer, Marianne. 2012. Who is greener? Climate action and political regimes: trade-offs for national and international actors. Democratization 19:865–888. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2012.709686.

Kneuer, Marianne, and Sebastian Harnisch. 2016. Diffusion of e‑government and e‑participation in democracies and autocracies. Global Policy 7:548–556. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12372.

Knutsen, Carl Henrik, and Hanne Fjelde. 2013. Property rights in dictatorships: kings protect property better than generals or party bosses. Contemporary Politics 19:94–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2013.773205.

Lafferty, William M., and James Meadowcroft (eds.). 1997. Democracy and the environment: problems and prospects. Cheltenham: Elgar.

Le, Thai-Ha, Youngho Chang, and Donghyun Park. 2016. Trade openness and environmental quality: International evidence. Energy Policy 92:45–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2016.01.030.

Leinaweaver, Justin. 2012. Environmental treaty ratification: treaty design, domestic politics and international incentives. SSRN Scholarly Paper.. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2035531.

Leitão, Alexandra. 2010. Corruption and the environmental Kuznets curve: empirical evidence for sulfur. Ecological Economics 69:2191–2201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.06.004.

Levitsky, Steven, and A. Way Lucan. 2015. The myth of democratic recession. Journal of Democracy 26:45–58. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2015.0007.

Li, Quan, and Rafael Reuveny. 2006. Democracy and environmental degradation. International Studies Quarterly 50:935–956.

Lüdecke, Daniel. 2018. Data visualization for statistics in social science

Lueders, Hans, and Aurel Croissant. 2014. Wahlen, Strategien autokratischer Herrschaftssicherung und das Überleben autokratischer Regierungen. Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 8:329–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-014-0228-3.

Lv, Zhike. 2017. The effect of democracy on CO2 emissions in emerging countries: does the level of income matter? Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 72:900–906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.01.096.

Magaloni, Beatriz. 2006. Voting for autocracy: hegemonic party survival and its demise in Mexico. Cambridge studies in comparative politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511510274.

McGuire, James W. 2013. Political regime and social performance. Contemporary Politics 19:55–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2013.773203.

Meadowcroft, James. 2014. Comparing environmental performance. In State and environment, 27–52. The Comparative Study of Environmental Governance: MIT Press.

Midlarsky, Manus I. 1998. Democracy and the environment: an empirical assessment. Journal of Peace Research 35:341–361.

Miller, Michael K. 2015. Elections, information, and policy responsiveness in autocratic regimes. Comparative Political Studies 48:691–727. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414014555443.

Morrow, James D., Bruce Bueno De Mesquita, Randolph M. Siverson, and Alastair Smith. 2008. Retesting selectorate theory: separating the effects of W from other elements of democracy. American Political Science Review 102:393–400. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055408080295.

Neumayer, Eric. 2002. Do democracies exhibit stronger international environmental commitment? A cross-country analysis. Journal of Peace Research 39:139–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343302039002001.

Nieuwenhuis, Rense, Manfred de Grotenhuis, and Ben Pelzer. 2012. influence.ME: tools for detecting influential data in mixed effects models. The R Journal 4:38–47.

Ofosu, George Kwaku. 2019. Do fairer elections increase the responsiveness of politicians? American Political Science Review 113:963–979. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055419000479.

Payne, Rodger A. 1995. Freedom and the environment. Journal of Democracy 6:41–55. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.1995.0053.

Peng, Benhong, Xin Sheng, and Guo Wei. 2020. Does environmental protection promote economic development? From the perspective of coupling coordination between environmental protection and economic development. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 27:39135–39148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-09871-1.

Policardo, Laura. 2016. Is democracy good for the environment? Quasi-experimental evidence from regime transitions. Environmental and Resource Economics 64:275–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-014-9870-0.

Povitkina, Marina. 2018. The limits of democracy in tackling climate change. Environmental Politics 27:411–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2018.1444723.

Prichard, Wilson. 2018. Electoral competitiveness, tax bargaining and political incentives in developing countries: evidence from political budget cycles affecting taxation. British Journal of Political Science 48:427–457. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123415000757.

R Core Team. 2017. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Roller, Edeltraud. 2013. Comparing the performance of autocracies: issues in measuring types of autocratic regimes and performance. Contemporary Politics 19:35–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2013.773201.

Rydén, Oskar, Alexander Zizka, Sverker C. Jagers, Staffan I. Lindberg, and Alexandre Antonelli. 2020. Linking democracy and biodiversity conservation: Empirical evidence and research gaps. Ambio 49:419–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-019-01210-0.

Schedler, Andreas. 2013. The politics of uncertainty: sustaining and subverting electoral authoritarianism. Oxford University Press.

Schmidt, Manfred G. 2012. Legitimation durch Performanz? Zur Output-Legitimität in Autokratien. Totalitarismus und Demokratie 9:83–100.

Scruggs, Lyle A. 1999. Institutions and environmental performance in seventeen western democracies. British Journal of Political Science 29:1–31.

Selden, Thomas M., and Daqing Song. 1994. Environmental Quality and Development: Is There a Kuznets Curve for Air Pollution Emissions? Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 27:147–162. https://doi.org/10.1006/jeem.1994.1031.

Soest, Christian von, and Julia Grauvogel. 2017. Identity, procedures and performance: how authoritarian regimes legitimize their rule. Contemporary Politics 23:287–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2017.1304319.

Stern, David. 2014. The Environmental Kuznets Curve: A Primer. CCEP Working Paper. Centre for Climate Economics & Policy, Crawford School of Public Policy, The Australian National University.

Stein, Jana von. 2020. Democracy, autocracy, and everything in between: how domestic institutions affect environmental protection. British Journal of Political Science 51:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000712342000054X.

Stier, Sebastian. 2017. Internet diffusion and regime type: temporal patterns in technology adoption. Telecommunications Policy 41:25–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2016.10.005.

Tennekes, Martijn. 2018. tmap: thematic maps in R. Journal of Statistical Software 84:1–39. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v084.i06.

Thompson, Janna. 1995. Towards a green world order: environment and world politics. Environmental Politics 4:31–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644019508414227.

Torras, Mariano, and James K. Boyce. 1998. Income, inequality, and pollution: a reassessment of the environmental Kuznets Curve. Ecological Economics 25:147–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8009(97)00177-8.

Ward, Hugh. 2008. Liberal democracy and sustainability. Environmental Politics 17:386–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644010802055626.

Wendling, Zachery A., W. Emerson John, Daniel C. Esty, Marc A. Levy, and Alex M. de Sherbinin. 2018. Environmental performance index

Whitford, Andrew B., and Karen Wong. 2009. Political and social foundations for environmental sustainability. Political Research Quarterly 62:190–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912908318322.

Winslow, Margrethe. 2005. Is democracy good for the environment? Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 48:771–783. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640560500183074.

Wintrobe, Ronald. 2007. Dictatorship: analytical approaches. In The oxford handbook of comparative politics, ed. Carles Boix, Susan C. Strokes, 363–394. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Worldbank. 2019. World development indicators

Wurster, Stefan. 2011. Sustainability and regime type: do democracies perform better in promoting sustainable development than autocracies? Zeitschrift für Staats- und Europawissenschaften 9:538–559. https://doi.org/10.5771/1610-7780-2011-4-538.

Wurster, Stefan. 2013. Comparing ecological sustainability in autocracies and democracies. Contemporary Politics 19:76–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2013.773204.

Wurster, Stefan. 2019. Autokratische Varianten des Wohlfahrtsstaates. In Handbuch Sozialpolitik, ed. Herbert Obinger, Manfred G. Schmidt, 315–333. Wiesbaden: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-22803-3_17.

Wurster, Stefan, Benjamin Auber, Laura Metzler, and Christian Rohm. 2015. Institutionelle Voraussetzungen nachhaltiger Politikgestaltung. Zeitschrift für Politik 62:177–196.

Wurster, Stefan. 2010. Sparen Demokratien leichter? – Die Nachhaltigkeit der Finanzpolitik von Demokratien und Autokratien im Vergleich. dms – der moderne staat – Zeitschrift für Public Policy, Recht und Management 5:269–290.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this article have been presented at the 12th Annual Graduate Conference in Political Science, International Relations and Public Policy and the 69th PSA Annual International Conference’ (Un)Sustainable Politics in a Changing World’. We would like to thank the participants, especially Tanya Heikkila and Stefan Wurster, for their comments which helped us to improve our article substantially. Furthermore, we would like to thank three anonymous reviewers for their constructive criticism during the process of publication.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

K. Eichhorn and E. Linhart declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Eichhorn, K., Linhart, E. Autocratic heterogeneity in the provision of environmental protection. Z Vgl Polit Wiss 16, 5–30 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-022-00519-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-022-00519-7