Summary

Ovarian cancer (OC) management presents a challenging scenario in clinical practice due to its late diagnosis, high recurrence rate, and dismal 5‑year survival rate of 45%—especially in platinum-resistant cases. Antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) are novel drugs that enable the selective delivery of potent cytotoxic agents directly to tumor cells, thereby maximizing treatment effectiveness while minimizing harm to healthy cells. Recent studies have shown promising results in this regard. Mirvetuximab soravtansine achieved remarkable results in the MIRASOL trial, suggesting it as a potential new standard of care for folate receptor-α-positive platinum-resistant OC treatment. Furthermore, trastuzumab deruxtecan demonstrated promising results in the PanTumor02 trial, showing clinically meaningful efficacy across a broad spectrum of HER2-positive solid tumors. This review article explores the current state of ADCs in ovarian cancer and their potential to improve outcomes in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer, especially in the platinum-resistant setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

More than a century ago Paul Ehrlich, the winner of the Nobel Price of Medicine in 1908, had the vision to link a cytotoxic payload to a factor with selective affinity to the pathogen, this concept was also known as “the magic bullet”. Antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) seem to have the potential to implement this vision into modern cancer treatment; they are formed by three main components: (I) a therapeutic monoclonal antibody, (II) a potent cytotoxic agent (payload) and (III) a spacer arm as linker [1]. Owing to their complex design, which enables the selective delivery of potent cytotoxic agents directly to tumor cells, ADCs are promising drugs in cancer treatment by maximizing their effectiveness while minimizing harm. In 2009, gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg®) was the first approved ADC by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [2]. At the time of writing this article, 13 ADCs were globally approved, including one labelled and three in late-stage studies for OC [3].

Due to its late diagnosis, high recurrence rate, and dismal 5‑year survival rate of 45% [4], ovarian cancer (OC) management poses a challenge. Especially after tumors lose their responsiveness to platinum-based therapy. In this case, therapeutic options are highly limited since platinum-resistant OC (PROC) develop multidrug-resistance leading to poor response after additional systematic chemotherapy [5].

Although targeted therapies, such as PARP inhibitors and the VEGF-inhibitor bevacizumab, have improved outcomes in OC patients, many still experience recurrent disease [6]. Due to this high resistance rate, new therapeutic options and identification of additional biomarkers are of urgent need to improve the outcome of PROC.

Mirvetuximab soravtansine: the game changer

Currently, the primary therapies for PROC contain nonplatinum chemotherapy, either as a single agent or in combination with bevacizumab [7]. The results of the AURELIA study, an open-label randomized phase III trial, showed significant improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients with PROC when bevacizumab was added to the physician’s-choice chemotherapy [8, 9]. Since then, no new agents have been approved for PROC, leaving a large gap in OC treatment [7].

Mirvetuximab soravtansine (MIRV) is a potential “gap-filler”—a humanized FRα antibody with a cleavable linker and DM4, a tubulin-targeting agent, as payload. Binding to FRα leads to ADC internalization and DM4 release, which disrupts tubulin polymerization and microtubule assembly, causing microtubule destabilization, mitotic blockade, cell arrest, and apoptosis. Maytansinoids were unsuccessful as anticancer agents due to systemic toxicity, yet their high stability and solubility make them suitable for use in ADCs [9]. DM4 can spread from antigen-positive tumor cells, killing nearby cells irrespective of their antigen status, known as the “bystander” effect [10].

FRα is a cell surface glycoprotein that binds folates. Although its physiological role in nonmalignant and cancerous tissues remains unclear, most normal tissues do not express FRα [11]. In contrast to this, over 90% of OC showed FRα expression [12], with 36% of PROC tumors showing higher FRα expression. In addition, FRα is usually not expressed in normal ovarian epithelium, making it a potent target for OC treatment [13]. Notaro et al. were unable to reveal prognostic relevance of FRα expression in high-grade OC, but higher expression was associated with advanced Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et dʼObstétrique (FIGO) stage III and IV disease and serous subtype. Interestingly, in low-grade OC high FRα expression was found to predict platinum sensitivity and improved clinical outcome, especially in advanced disease [14].

On November 14, 2022, MIRV obtained accelerated FDA approval for use in adult FRα-positive, platinum-resistant ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer patients who had received one to three prior treatment lines [15]. The approval was based on the results of the SORAYA trial [16], an open-label, single-arm, phase III trial. The study included 106 patients with PROC, expressing high levels of FRα (i.e., ≥ 75% of cells with ≥ 2+ staining intensity) after one to three prior lines of treatment. Prior exposure to bevacizumab was obligatory, prior exposure to PARP inhibitors was allowed. The primary endpoint was objective response rate (ORR); secondary endpoints included PFS, OS, and safety. After a median follow-up of 13.4 months, MIRV demonstrated an ORR of 32% (95% confidence interval [CI] 23.6–42.2) which includes five complete responses (CR) and median duration of response (DOR) of 6.9 months (95% CI 5.6–9.7). Notably, drug activity was observed in patients regardless of the number of previous therapies or exposure to PARP inhibitors [7].

To gain global approval and to confirm the effectiveness of MIRV compared to investigator’s choice of chemotherapy (IC), the MIRASOL (GOG 3045/ENGOT-ov55) trial was initiated—a global, randomized phase III study, the results of which were presented at the 2023 ASCO Annual Meeting [17].

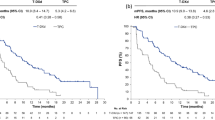

With a median follow-up of 13.1 months, 227 and 226 patients were randomized to the MIRV and IC arms, respectively. The ORR was 42% (95% CI 5.8–49.0%) compared to 16% (95% CI 11.4–21.4%), respectively (p < 0.0001), including 12 CR in the MIRV compared to zero in the IC arm. Median PFS was 5.62 months (95% CI 4.34–5.95) in the MIRV arm compared to 3.98 (95% CI 2.86–4.47) in the IC arm (hazard ratio [HR] 0.65, 95% CI 0.52–0.81; p < 0.0001), which indicates an improvement of 35%. Median OS for MIRV arm and IC arm was 16.46 months (95% CI 14.46–24.57) and 12.75 months (95% CI 10.91–14.36), respectively (HR 0.67; 95% CI 0.50–0.89; p = 0.0046). PFS and OS also showed a benefit for the MIRV arm in BEV-naïve and BEV-pretreated subgroups [17].

With over 1000 patients in the database, MIRV’s safety profile keeps showing mainly low-grade ocular, gastrointestinal, and neuropathy events.

The MIRASOL trial showed significantly improved PFS, ORR, and OS, including a 33% OS increase, marking it the first PROC treatment since the AURELIA study, which presented an OS benefit in a phase III trial. The authors propose MIRV as a potential new standard of care for FRα-positive PROC treatment, citing its potential to revolutionize the field. However, caution should be taken, as ADC therapies are new treatments, and many clinical aspects are unknown. The cleavable linker in MIRV may cause premature release of DM4, leading to peripheral and systemic toxicity and reducing therapeutic concentration. This may explain the ocular adverse drug reactions. MIRV can also cause side effects by binding to tissues with high FRα expression, such as the choroid plexus, lung, thyroid, and kidney. This may explain severe side effects such as neuropathy and pneumonitis [10].

The allrounder: trastuzumab deruxtecan

Trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) achieved remarkable results in the DESTINY-Breast04 trial, causing standing ovation at the 2022 ASCO Annual Meeting Plenary Session talk by doubling the PFS and significantly improving OS in patients with pretreated HER2-low metastatic breast cancer. This does not only offer a new treatment option but also establishes HER2-low as a new therapeutic target for metastatic breast cancer. The T‑DXd payload is a topoisomerase I inhibitor (such as irinotecan and topotecan) linked to a humanized anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody via a cleavable tetrapeptide linker [18].

T‑DXd is approved for metastatic/unresectable HER2+ breast, gastric/gastroesophageal junction, and HER2-mutant non-small cell lung cancer. T‑Dxd efficacy is likely applicable to other solid tumors due to HER2 expression. The DESTINY-PanTumor02 trial is the first global trial to assess T‑DXd tumor-agnostic use across HER2-expressing solid tumors. This phase 2 study involved patients with advanced or metastatic HER2-expressing solid tumors including OC which progressed after ≥ 1 systemic treatment or had no treatment options.

After a follow-up of 9.8 months, 267 patients had been treated. In patients with OC, the ORR was 45% and mDOR was 11.3 months, including 4 CR. T‑DXd exhibited clinically meaningful efficacy across a broad spectrum of HER2-positive solid tumors, including those that are difficult to treat. This implies that T‑DXd could be a potential new treatment option for patients with HER2-expression solid tumors, regardless of tumor entity [19].

Promising future: farletuzumab ecteribulin and luveltamab tazevibulin

Currently, there are over 140 agents in clinical trials [3]; certainly, there are several promising targets that hold great potential for improving the treatment landscape in OC. However, to date, only few ADCs have been successful in large clinical trials. For example, anetumab ravtansine, a human antibody that targets mesothelin, failed in a phase II study. Bevacizumab and weekly anetumab ravtansine (ARB) were compared with bevacizumab and weekly paclitaxel (PB) in PR or refractory OC. PB yielded better results than ARB, leading to premature study closure [20].

More favorable results were shown with farletuzumab ecteribulin (MORAb-202), an ADC made up of the humanized anti-human FRα farletuzumab linked to eribulin by a cathepsin‑B cleavable linker [21].

ADCs with microtubule-targeting agents (MTA) as a payload have faced efficacy or toxicity issues, prompting new MTA payload research. MORAb-202 demonstrated strong properties and potency across FRα-positive tumor cell lines, improving in vitro specificity compared to farletuzumab with other MTAs [22].

After showing antitumor activity in OC patients (Shimizu 2021, CCR), 0.9 mg/kg (cohort 1 n = 24) and 1.2 mg/kg (cohort 2 n = 21) doses were chosen for the expansion part of this study (NCT03386942), based on efficacy and safety. Patients were included who had received ≤ 2 regimens of chemotherapy after diagnosis of PROC and were required to be FRα positive (> 5% of 1+ to 3+ intensity by IHC). Despite the small patient number, antitumor activity was seen in both cohorts. Low-grade interstitial lung disease/pneumonitis was the most common treatment emergent-adverse event [21].

The STRO-002-GM1 phase 1 study evaluated luveltamab tazevibulin in recurrent epithelial OC including patients with advanced, pretreated platinum-resistant or platinum-sensitive disease. A post hoc analysis of tissue found that STRO-002 was effective at both dosage levels, with a higher response rate at 5.2 mg/kg compared to 4.3 mg/kg (43.8 vs. 31.3%, respectively). A FRα-cutoff of > 25% was determined optimal for enrichment, suggesting STRO-002 is effective in lower FRα-expressing cancers [23]. Table 1 provides an overview of all ADC trials mentioned in this article.

Conclusion

Antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) hold promising therapeutic potential for ovarian cancer (OC) and can help fill gaps in the therapeutic landscape especially in the platinum-resistant setting. Their introduction is a step towards “therapy beyond tumor entity”, as has been demonstrated for trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd). While some aspects of tolerability remain uncertain, it could be expected that ADCs will be used in the future as widely as current cytostatic drugs, provided tumor tissue is targetable by the respective antibodies.

Take home message

ADCs offer potential for platinum-resistant OC treatment. They represent a step towards “therapy beyond tumor entity”, if tumor tissue is targetable, as T‑DXd demonstrated. Uncertainties about tolerability remain.

Abbreviations

- ADCs:

-

Antibody–drug conjugates

- FDA:

-

US Food & Drug Administration

- FRα:

-

Folate receptor‑α

- IC:

-

Investigator’s choice of chemotherapy

- MIRV:

-

Mirvetuximab soravtansine

- MTA:

-

Microtubule-targeting agents

- OC:

-

Ovarian cancer

- ORR:

-

Objective response rate

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- PROC:

-

Platinum-resistant ovarian cancer

- T‑DXd:

-

Trastuzumab deruxtecan

References

Joubert N, Denevault-Sabourin C, Bryden F, Viaud-Massuard MC. Towards antibody-drug conjugates and prodrug strategies with extracellular stimuli-responsive drug delivery in the tumor microenvironment for cancer therapy. Eur J Med Chem. 2017;142:393–415.

Joubert N, Beck A, Dumontet C, Antibody-Drug Conjugates D‑SC. The Last Decade. Pharm (basel). 2020;13(9).

Dumontet C, Reichert JM, Senter PD, Lambert JM, Beck A. Antibody-drug conjugates come of age in oncology. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2023;22(8):641–61.

Karpel HC, Powell SS, Pothuri B. Antibody-Drug Conjugates in Gynecologic Cancer. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2023;43:e390772.

Li J, Zou G, Wang W, Yin C, Yan H, Liu S. Treatment options for recurrent platinum-resistant ovarian cancer: A systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis based on RCTs. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1114484.

Tsibulak I, Zeimet AG, Marth C. Hopes and failures in front-line ovarian cancer therapy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2019;143:14–9.

Matulonis UA, Lorusso D, Oaknin A, Pignata S, Dean A, Denys H, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Mirvetuximab Soravtansine in Patients With Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer With High Folate Receptor Alpha Expression: Results From the SORAYA Study. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(13):2436–45.

Pujade-Lauraine E, Hilpert F, Weber B, Reuss A, Poveda A, Kristensen G, et al. Bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy for platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer: The AURELIA open-label randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(13):1302–8.

Moore KN, Borghaei H, O’Malley DM, Jeong W, Seward SM, Bauer TM, et al. Phase 1 dose-escalation study of mirvetuximab soravtansine (IMGN853), a folate receptor α‑targeting antibody-drug conjugate, in patients with solid tumors. Cancer. 2017;123(16:3080–7.

Nwabufo CK. Mirvetuximab soravtansine in ovarian cancer therapy. opinion on pharmacological considerations. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol: expert; 2023.

Ab O, Whiteman KR, Bartle LM, Sun X, Singh R, Tavares D, et al. IMGN853, a Folate Receptor‑α (FRα)-Targeting Antibody-Drug Conjugate, Exhibits Potent Targeted Antitumor Activity against FRα-Expressing Tumors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14(7):1605–13.

Markert S, Lassmann S, Gabriel B, Klar M, Werner M, Gitsch G, et al. Alpha-folate receptor expression in epithelial ovarian carcinoma and non-neoplastic ovarian tissue. Anticancer Res. 2008;28(6A):3567–72.

Vergote IB, Marth C, Coleman RL. Role of the folate receptor in ovarian cancer treatment: evidence, mechanism, and clinical implications. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2015;34(1):41–52.

Notaro S, Reimer D, Fiegl H, Schmid G, Wiedemair A, Rössler J, et al. Evaluation of folate receptor 1 (FOLR1) mRNA expression, its specific promoter methylation and global DNA hypomethylation in type I and type II ovarian cancers. Bmc Cancer. 2016;16:589.

Administration FD. FDA grants accelerated approval to mirvetuximab soravtansine-gynx for FRα positive, platinum-resistant epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancer 11/14. Available From. 2022;. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-mirvetuximab-soravtansine-gynx-fra-positive-platinum-resistant).

Matulonis U, Lorusso D, Oaknin A, Pignata S, Denys H, Colombo N, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Mirvetuximab Soravtansine in Patients with Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer with High Folate Receptor Alpha Expression: Results from the SORAYA Study (LBA 4). Gynecol Oncol. 2022;166:S50.

Moore KN, Angelergues A, Konecny GE, Banerjee SN, Pignata S, Colombo N, et al. Phase III MIRASOL (GOG 3045/ENGOT-ov55) study: Initial report of mirvetuximab soravtansine vs. investigator’s choice of chemotherapy in platinum-resistant, advanced high-grade epithelial ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancers with high folate receptor-alpha expression. JCO. 2023 Jun 10;41(17_suppl):LBA5507. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2023.41.17_suppl.LBA5507

Modi S, Jacot W, Yamashita T, Sohn J, Vidal M, Tokunaga E, et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-low advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(1):9–20.

Meric-Bernstam F, Makker V, Oaknin A, Oh D‑Y, Banerjee SN, Gonzalez MA, et al. Efficacy and safety of trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) in patients (pts) with HER2-expressing solid tumors: DESTINY-PanTumor02 (DP-02) interim results. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41.

Lheureux S, Alqaisi H, Cohn DE, Chern J‑Y, Duska LR, Jewell A, et al. A randomized phase II study of bevacizumab and weekly anetumab ravtansine or weekly paclitaxel in platinum-resistant or refractory ovarian cancer NCI trial#10150. J Clin Oncol. 2022;.

Nishio S, Yunokawa M, Matsumoto K, Takehara K, Hasegawa K, Hirashima Y, et al. Safety and efficacy of MORAb-202 in patients (pts) with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer (PROC): Results from the expansion part of a phase 1 trial. JCO. 2022;40.

Cheng X, Li J, Tanaka K, Majumder U, Milinichik AZ, Verdi AC. et al. MORAb-202, an Antibody-Drug Conjugate Utilizing Humanized Anti-human FRα Farletuzumab and the Microtubule-targeting Agent Eribulin, has Potent Antitumor Activity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2018;17(12):2665–75.

Oaknin A, Fariñas-Madrid L, García-Duran C, Martin LP, O’Malley DM, Schilder RJ, et al. Luveltamab tazevibulin (STRO-002), an anti-folate receptor alpha (FolRα) antibody drug conjugate (ADC), safety and efficacy in a broad distribution of FolRα expression in patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer (OC): Update of STRO-002-GM1 phase 1 dose expansion cohort. JCO. 2023 Jun 1;41(16_suppl):5508. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.5508

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Innsbruck and Medical University of Innsbruck.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

B. Feroz reports travel expenses from Roche, Pfizer and Lilly. A. Zeimet reports consulting fees from Amgen, Astra Zeneca, GSK, MSD, Novartis, PharmaMar, Roche-Diagnostics, Seagen; honoraria from Amgen, Astra Zeneca, GSK, MSD, Novartis, PharmaMar, Roche, Seagen; travel expenses from Astra Zeneca, Gilead, Roche; participation on advisory boards from Amgen, Astra Zeneca, GSK, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, PharmaMar, Roche, Seagen. C. Marth reports consulting fees from Roche, Novartis, Amgen, MSD, PharmaMar, Astra Zeneca, GSK, Seagen; honoraria from Roche, Novartis, Amgen, MSD, PharmaMar, Astra Zeneca, GSK, Seagen; travel expenses from Roche, Astra Zeneca; participation on advisory boards from Roche, Novartis, Amgen, MSD, Astra Zeneca, Pfizer, PharmaMar, GSK, Seagen. The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Feroz, B., Marth, C. & Zeimet, A.G. Antibody–drug conjugates in ovarian cancer. memo 17, 130–134 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12254-024-00959-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12254-024-00959-9