Abstract

Considering the problems associated with school attendance, school refusal is an adjustment problem that tends to become increasingly prevalent. The present study identifies the patterns reported in the literature on school refusal and outlines the structure and sub-components of school refusal. Therefore, the systematic review method was selected as the research method for this study. The data sources of this study consist of 40 research articles that fell within the purview of WoS and were either included or excluded according to predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Using MAXQDA 2020, both content and descriptive analyses were conducted in synthesizing the data sources. As a result of the analysis, the study year, method, data collection tool, data collection procedure, data analysis, and sample were examined as descriptive characteristics. Analyzing the content characteristics, five themes were identified: risk factors for school refusal, school refusal symptoms, school refusal protective factors, approaches, and techniques for intervention in school refusal, and consequences of school refusal. The findings are provided by discussing the related literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Refusing to go to school or having trouble focusing and staying on schoolwork for an entire school day is a symptom of school refusal, which is a frequent mental health issue originating from anxiety and fear (Kearney, 2008; Kearney & Albano, 2004). Although school phobia and truancy are discussed in the literature as possible explanations for attendance issues, Kearney (2007) proposed the term “school refusal.” In this sense, “school refusal” refers to a child’s reluctance to attend school or the difficulty the child has in spending most of the day in the classroom. School refusal is a significant problem affecting approximately 1–5% of all school-aged children, with similar prevalence rates between the sexes, and it tends to be more prevalent among children aged between 5 and 10 years (Fremont, 2003). In another study, the percentage of children having the problem of absenteeism due to school refusal was reported to be 4% (Havik et al., 2015).

In this context, the behavioral symptoms listed are primarily associated with anxiety. Anxiety can manifest itself in children through different levels of behavioral, physiological, and emotional reactions. Separation anxiety, which is a natural consequence of dysfunctional attachment processes between parents and children, is considered as an essential factor in school refusal (Bitsika et al., 2022). Negative emotions and disruptive behaviors such as anger or aggression (Heyne & Boon, 2023), social withdrawal (Benarous et al., 2022), sleep problems (Maeda et al., 2019), difficulty in focusing, and dysphoria may accompany a child’s school refusal (Nayak et al., 2018). In addition, emotional instability intense sensitivity in interpersonal relationships, problems in relationships with peers and feelings of loneliness, exposure to peer bullying (Bitsika et al., 2022; Ochi et al., 2020), and low academic performance (Filippello et al., 2020) can be listed as factors that increase the susceptibility of students to experience school refusal.

School refusal, which is associated with school dropout, has a pattern associated with conditions such as substance use, the tendency to violence, suicidality, risky sexual behaviors, involvement in crime, anxiety disorders, psychological adjustment problems (Seçer & Ulaş, 2020), and anti-social behavior development (Rocque et al., 2017). According to these findings, students’ problematic school absenteeism is linked to various demographic, behavioral, and academic factors (Seçer & Ulaş, 2020). It was reported that the reasons for children experiencing school refusal to resort to these behaviors are to attract the attention of other important people (55.1%), avoid stimuli that trigger negative affect (20.4%), and seek concrete reinforcements outside of school (20.4%) (Kearney et al., 2005).

An increasing number of studies are carried out, indicating that school refusal is a negativity that threatens young people’s academic and everyday lives in both short and long term (Fernández-Sogorb et al., 2022; Fujita et al., 2022; Gonzálvez et al., 2023; Elliott & Gainor, 2023; Leduc et al., 2022; Tekin & Aydın, 2022). It was reported that it is challenging to return students, who have not attended school for a while, that the child may experience an intense feeling of helplessness in the face of accumulated homework and the amount of work that needs to be compensated, and that there may be a feeling of not belonging to and stress due to the thought of being socially isolated from their classmates. Moreover, a child’s refusal to attend school often causes distress and tension among family members in the short term. It requires parents to constantly have a dialogue with counselors, school psychologists, principals, teachers, and other educators (Kearney, 2007). Long-term effects may include the child’s engagement in criminal activities and/or dropping out of school. School dropout is considered to be a severe problem in an individual’s life and may cause negative personal and interpersonal problems. In adulthood, one may encounter unemployment, decline in social functioning, psychological issues, substance abuse, financial difficulties, and decline in family functioning (Rocque et al., 2017).

Risk factors related to school refusal

In a review study carried out by Ingul et al. (2019) aiming to identify risk factors of and early symptoms related to school refusal, it was reported that early symptoms of school refusal include school absenteeism, somatic complaints, depression, and anxiety. In addition, the study listed the risk factors for school refusal as the transition process between school levels, difficulties in emotional regulation, low self-efficacy, negative thinking tendency, inadequate problem-solving skills, insufficient teacher support and supervision, unpredictability of school experiences, bullying, social isolation, loneliness, inadequate collaboration between home and school, parent’s psychological well-being, excessive parental protection, and dysfunctional family processes. Furthermore, empirical studies revealed that perceived social support from teachers, parents, and classmates, parental demand level, test anxiety (Nwosu et al., 2022; Havik et al., 2015), and low family functionality (Gonzálves et al., 2019) are also risk factors for school refusal.

The assessment conducted by Filippello et al. (2018) indicated that causal relationships between personal characteristics and school refusal have not yet been deeply established. In this regard, personality traits, emotional regulation, and emotional intelligence characteristics have been subjected to risk analysis for school refusal. The findings showed that neurotic personality structure and inappropriate emotional regulation strategies are risk factors for school refusal. Gonzálves et al. (2019), in a profile analysis of risks for school refusal, reported that social anxiety is an important risk factor for school refusal. Additionally, neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder can also be considered a risk factor for school refusal. A study comparing school refusal behaviors of typically developing children and those diagnosed with autism found that children with autism exhibit higher levels of school refusal (Munkhaugen et al., 2017). It highlights the need for diversifying the sample structure in school refusal research.

Empirical studies on school refusal

Given that school refusal is considered a problem within school attendance issues and its effects can persist throughout one’s lifetime, an assessment can be made regarding the importance of empirical studies on school refusal. Examining the relevant literature, review studies indicate that experimental studies examining school refusal lack a strong scientific basis (Maynard et al., 2014) and predominantly favor cognitive-behavioral therapy (Heyne et al., 2020; Maynard et al., 2014). Despite the effectiveness of this therapeutic approach for conditions such as depression and anxiety, it is considered inadequate for school refusal due to its heterogeneous nature, thus requiring specific interventions (Heyne & Sauter, 2013). However, experimental studies demonstrated the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy in improving school refusal (Maynard et al., 2015). The “Back2School” program, developed as an adaptation of cognitive-behavioral therapy, was created aiming to ensure school attendance and effectively intervened with 60 children aged 7 to 16 years as part of the program (Thastum et al., 2019).

Dialectical behavior therapy is a more contemporary approach when compared to cognitive-behavioral therapy for school refusal. In this approach, a multi-component structure is utilized in order to directly address the emotional and behavioral dysregulation mechanisms that sustain school refusal behavior. Furthermore, it includes real-time coaching for the child and the parent as needed and in context (Chu et al., 2015). It was determined that the age of the child is an important factor for the success of intervention approaches and younger children benefit more (Maynard et al., 2015). Thus, Ulaş (2022) carried out a study involving parent-child interaction therapy for preschool children’s school refusal behavior and this method was reported to be effective. Therefore, it can be stated that early interventions are crucial for addressing problematic behaviors and parent-mediated interaction-based interventions have gained prominence in addressing childhood behavioral and emotional problems in recent times (Niec, 2018).

The present study

Although school plays a significant role in determining an individual’s life path, actions such as school refusal can negatively affect these processes. Therefore, it is necessary to detect, intervene, and prevent problems, such as school refusal, at an early stage. However, it can be stated that studies on school refusal in the literature have been carried out using either a relational pattern (Filippello et al., 2019, 2020; Seçer & Ulaş, 2020) or a descriptive pattern (Delgado et al., 2019; Gonzálvez et al., 2021a, b; Nwosu et al., 2022), and studies carried out using an applied or experimental design (Roué et al., 2021; Strömbeck et al., 2021) can be considered a minority in this comparison. However, it indicates that there has been very little progress in school refusal treatment within our century, and the reason for this is the heterogeneous nature of this problem (Elliot & Place, 2018; Nwosu et al., 2022).

Therefore, Inglés et al. (2015) suggested carrying out studies on the establishment of a conceptual and theoretical framework regarding school refusal. In this parallel, the present study aims to present the overall framework of patterns and heterogeneous structure of the existing literature on school refusal, including experimental or descriptive research articles. Furthermore, when compared to systematic review studies carried out to date, the study carried out by Li et al. (2021) focused on identifying somatic symptoms related to school refusal. The systematic review study carried out by Leduc et al. (2022) analyzed school refusal from an ecological perspective. Tekin and Aydın (2022) aimed to determine the patterns of relationships between school refusal and anxiety. Ingul et al. (2019), on the other hand, focused on school-based risk factors and early symptoms related to school refusal. In this study as well, taking a holistic perspective, the consideration of risk factors, protective factors, symptoms, and intervention efforts related to school refusal can be regarded as a distinguishing feature from other studies in the literature. In addition, the use of MAXQDA analysis software in the analysis process of this study can be considered an innovative aspect for systematic review studies.

The literature suggests that there are various types of school attendance problem (school refusal, truancy, school phobia, dropout, school withdrawal, etc.) and they should be distinguished from each other (Heyne, 2019). In this context, school refusal is considered a cause of public health problems such as school dropout (Thastum et al., 2019). Therefore, in this study, a search was made using the keywords of school refusal in order to reveal the general structure of the subject “school refusal”. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the research trends related to the problem area by analyzing research articles on school refusal in terms of their descriptive features and to reveal the structure of the concept of school refusal through content and descriptive analysis to synthesize the findings of the studies. The questions to be answered during the research are “What are the scientific research trends on school refusal?” and “What are the structure and components of school refusal?”

In this study, answering the research questions under investigation will allow for achieving significant findings in both theoretical and practical aspects, particularly in the field of educational psychology. At this point, the synthesis of literature on risk factors, protective factors, intervention approaches, outcomes, etc., related to school refusal problem will provide supportive insights for school psychologists and researchers in their preventive and intervention activities. Furthermore, it can be stated that the findings obtained here could serve as a guideline for education policymakers regarding certain regulations addressing school refusal, which is one of the issues of school attendance problems.

Materials and methods

This study was designed as a systematic review based on the objectives of the researchers. In a systematic review, what is currently known through previous studies on a subject or phenomenon is examined (Zawacki-Richter et al., 2020). Systematic review studies have some basic characteristics, such as the existence of a clearly defined set of objectives with predefined eligibility criteria, a clear and repeatable methodology, a systematic search aiming to identify all studies that will meet the eligibility criteria, an assessment of the validity of the findings of the included studies (for example, by assessing the risk of bias), and a systematic report and synthesis of the characteristics and findings of the studies included (Higgins & Green, 2008).

In this context, the steps followed in the research can be listed as determining the systematic review questions, drawing the conceptual framework, determining the inclusion criteria, determining the strategies for searching the studies, determining the studies to be examined, coding the studies, determining the nature of the included studies, and synthesis.

Data sources

The data sources of the present study were determined in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria given below.

The inclusion criteria are:

-

Being accessible with the “school refusal” keyword in Web of Science (WoS).

-

Being published between the years 2012 and 2021.

-

Being open access.

-

Being published in the English language.

The reasons for the inclusion criteria established by researchers are the use of current studies for the “time limitation”, accessing the complete records for “open access”, use of the universal language used in science for “the English language”, and the use of the most important scientific literature database for “Web of Science database” (Harzing & Alakangas, 2016).

The exclusion criteria are:

-

If the study accessed is not directly related to school refusal but found as a result of a search with a keyword; in other words, school refusal is not a basic variable for the study reached, but only in the text of the article,

-

Studies that are not research articles (reviews, thesis, editorial letters, or theoretical articles),

-

Scale adaptation studies,

-

Being published after May 2021,

-

Studies testing practices outside the field of psychology (e.g., pharmacological treatments).

The primary aim of researchers in determining the exclusion criteria is to access research articles directly related to education and psychology and studies examining the school refusal. For instance, studies that were identified through a search using the keyword of school refusal but are excluded from the scope of this study due to the fact that they only contain a mention of school refusal in the discussion section were not included. Preferring research articles as the source of data, the present study focuses on identifying and analyzing factors related to school refusal in accordance with the research objective.

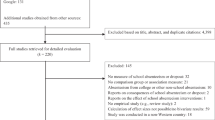

In this context, the stages of determining the data sources are given in Fig. 1 and the data sources of the study are presented in Table 1.

PRISMA flowchart. Page et al., (2021)

Study selection and data extraction

The Web of Science database was searched by two researchers in terms of titles and abstracts. Studies that were seem to not have not suitable titles or abstracts were excluded. The suitable ones were obtained in full-text format. Then, a detailed examination was conducted based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the study. The studies that fell within the scope of the research were independently coded by two researchers. Coding differences between the two researchers were discussed and resolved through consensus.

To address important threats to the reliability of the study, such as selection bias and reporting bias, all steps related to the included data sources were confirmed, discussed, and agreed upon among the researchers to mitigate these biases, ensuring the study’s credibility. Accordingly, both researchers played a role in determining whether the studies met the inclusion criteria. Both researchers worked together in the analysis and reporting of the obtained data sources. In this study, the researchers worked by coding the concrete data with the principle of accountability over the MAXQDA 2020 software to avoid the risk of bias. This project file is provided as an attachment.

Results

Following the searches based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, the researchers addressed 40 research articles presented in Table 1 within the scope of two separate research questions: the characteristics related to scientific research (methodology, data collection tools, etc.), and the characteristics related to the field of school refusal.

Results regarding research question 1

The first research question, “What are the scientific research trends in studies on school refusal?” was determined as the initial query to be answered. In this process, the researchers aimed to reveal the descriptive characteristics of studies on school refusal. The findings obtained in this direction are presented in Fig. 2.

Figure 2 shows that the researchers examined six different aspects of the studies that were data sources for this study: year, methodology, participants, data collection tools, data analysis methods, and data collection procedures.

Considering that the search for data sources was completed in May 2021, it can be stated that publications on school refusal exhibited an increasing trend. Examining the research methods used in those studies, it can be concluded that the studies primarily used quantitative research methods. In the category of data collection tools, which is a part of research methods, scales were preferred commonly and interviews were preferred rarely. However, a quantitative study provided no information about data collection. The data collection procedure, another category of the study, was carried out face-to-face mostly.

The data analysis category, on the other hand, is divided into sub-categories such as difference analysis, relational analysis, and qualitative data analysis. It can be said that regression analyses were mostly preferred in relational analyses. In the qualitative analysis subcategory includes thematic analysis, interpretive phenomenological analysis, and inductive analysis. In the data analysis category, it can be interpreted that differential analyses are used extensively.

The last category regarding the descriptive characteristics of the studies examined was the structure of the participants (sample). It can be seen that sampling consisted of preschool students, primary school students, high school students, the clinical group, students with special needs, healthcare professionals, school staff, and parents.

As a result, it was observed that the school refusal problem is a current problem area, and quantitative research methods and techniques have been employed in order to understand the heterogeneous nature of this problem. Furthermore, it is very important to carry out studies with a sample structure that includes students from all grade levels, students with special needs, as well as professionals and parents. This approach allows for a multi-dimensional assessment of school refusal.

Results regarding research question 2

The primary aim of this research is to create a pattern of variables related to school refusal through the content analysis of previous studies on school refusal. In this regard, the second research question being addressed is “What are the structure and components of school refusal?” In this process, the researchers aimed to synthesize the findings of studies on school refusal.

In the analysis process, the codes obtained from the data sources were grouped into five categories: risk factors for school refusal, symptoms of school refusal, protective factors for school refusal, consequences of school refusal, intervention techniques and approaches to school refusal. The findings are shown in Fig. 3.

Results regarding the risk factors for school refusal

Subcategories were created for the category of risk factors for school refusal: risk factors originating from individual characteristics, risk factors arising from environmental characteristics, and risk factors arising from family characteristics.

Exposure to peer bullying, reactive attachment disorder, perfectionism, low self-perception, lack of emotion and impulse control, difficult childhood experiences and trauma, depression, health-related factors, anxiety, and low self-efficacy codes were included in the risk factors arising from individual characteristics. Exposure to peer bullying was analyzed particularly as verbal and cyberbullying types, whereas anxiety was analyzed as general anxiety, school-related anxiety, and social anxiety (avoiding entering a new environment and negative emotions and being evaluated in all dimensions). In addition, in the category of health-related factors, among neurodevelopmental disorders, the autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder were included. In the category of childhood difficulties experienced and traumas, psychological fragility, behavioral disorders such as stealing, neuroticism, and learned helplessness were included.

Parental depression, negative living conditions, high expectations of the family from school, families not sharing the school mission, high-performance pressure from parents to the child, low education level of family, and living with a single parent at home codes are included in the risk factor subcategory arising from family characteristics.

The risk factors arising from environmental characteristics are the attendance of children with special needs in regular schools, social inequalities, the pressure on teachers to catch up with curriculum and being a minority from different cultures codes.

Category of symptoms for school refusal

The second category was determined as school refusal symptoms. Inadequate interactions between parents and children, intolerance to time spent in classroom, school-related anxiety, insufficient peer interaction, unpleasant feelings towards school, absenteeism, avoidance of school attendance, high-level aggression, and antisocial behavior codes were rated as the most common symptoms.

Category of factors for school refusal

The third category was determined to be a protective factor against school refusal. In this category, protective factors originating from individual characteristics, protective factors arising from environmental characteristics, and protective factors arising from family characteristics are included.

Effective friendships, having learning goals, extraversion, high self-esteem, having a well-adjusted profile, commitment to school values, prosocial behaviors, high academic endurance, high social skills, and high social functionality codes are some of the individual characteristics included in the protective factors. Positive perceptions of family function, high family harmony, high socioeconomic level, and effective teacher and family relationship codes are among the protective factors originating from family characteristics. Protective factors originating from environmental characteristics consist of codes such as positive teacher-student relationship, perceived teacher support, and early intervention for existing psychiatric problems.

Category of consequences of school refusal

Another category was the consequences of school refusal. This category consisted of social withdrawal, low academic achievement, depression, emotional exhaustion, and low school attachment codes. In this context, studies have shown that the depression code can be both a risk factor and a result of school refusal.

Category of intervention technics and approaches to school refusal

Finally, the categories of intervention techniques and approaches to school refusal were created, and the inclusion of trauma intervention techniques in school curriculum, school-based quick feedback practice, cognitive behavioral therapy, parent counseling, and time-out technique were determined as the codes in this category.

Conclusion and discussion

Figure 2 illustrates the results achieved from the examinations and analyses conducted to analyze the research tendencies of the studies conducted on school refusal, which is the first research question of the current study. It is important that studies on the causes and consequences of school refusal gained weight in recent years. When compared to other factors, significant attention has been paid to quantitative studies that analyze this phenomenon. This can be attributed to the fact that school refusal is a relatively new area of research in the literature. It is also one of the present study’s significant findings that there has not yet been any study with mixed methods research that aims to combine the strengths of quantitative and qualitative studies of school refusal. School refusal differs from other problems and its causality cannot be explained simply.

As a matter of fact, as a result of the conceptualization study by Karthika and Devi (2020), in which they sought the answer to the question of whether school refusal is a psychosocial or psychiatric problem, they framed school refusal as a comorbid problem with one or more psychiatric problems. Even though it is a psychiatric problem, it is not included as a separate diagnosis in the DSM-V or ICD-10 due to its heterogeneous causality and association with many problems (Roué et al., 2021).

Regarding the first research question, it was also determined that the sample structure preferred in the studies primarily included high school students (between the ages of 10 and 18), which corresponds to the adolescence period (Strömbeck et al., 2021; Seçer & Ulaş, 2020). When compared to other demographics, high school students are more likely to have a school refusal problem that eventually leads to dropouts because of the crucial responsibilities of their life stages. This may be why researchers have focused so much attention on the phenomenon of high school students’ school refusal. However, previous studies draw attention to the importance of early-period studies on the school refusal (Maynard et al., 2015). A study was also carried out not only with students but also with school staff, healthcare professionals, and parents (Devenney & O’Toole, 2021; Gallé-Tessonneau & Heyne, 2020) can be interpreted as the factors affecting the school refusal problem should be examined from a broad perspective.

As a result of the analyses conducted in order to determine the structure and components of school refusal, which was the second question of the study, school refusal was seen to have five components. Among individual risk factors, anxiety, depression, exposure to bullying, and health-related factors were the codes repeated frequently.

In this context, Devenney and O’Toole’s (2021) study on instructors concluded that there is a strong relationship between school refusal and anxiety, which may even be a traumatizing experience. The same study revealed that performance pressure on children, separation anxiety, and peer exclusion are significant predictors of school refusal. According to the results of a study carried out on adolescents by Delgado et al. (2019), children who were victims of cyberbullying had a higher level of school refusal in comparison to those who were not. In this context, it can be stated that social anxiety, which is closely related to bullying, is a significant risk factor for school refusal (Gonzálvez et al., 2019). Ochi et al. (2020), on the other hand, found that being exposed to bullying is an important risk factor for school refusal in children with autism as well as in children without developmental disorders.

Therefore, it can be stated that school refusal is accompanied by separation anxiety, which is one of the anxiety types, in younger age groups (5–12), whereas it is accompanied by social phobia in older age groups (13–16) (Ingul & Nordahl, 2013). In addition, situations that increase students’ susceptibility to school refusal include negative affectivity, intense sensitivity in interpersonal relationships, problems in relationships with peers, feelings of loneliness, emotional distress, depression, and low self-efficacy perception (Devenney & O’Toole, 2021; Bitsika et al., 2021).

When examining the familial risk factors associated with school refusal, it was determined that families with high-performance expectations from their children and inadequate engagement in basic school duties are significant risk factors. In this context, as reported in the study carried out by Ulaş and Seçer (2022), the high level of performance expectations of families leads students to be perfect and not tolerant of mistakes. As a result of the intense effort and sense of competition brought about by this, students’ school burnout was evaluated as inevitable. Thus, school burnout may be a risk factor for school refusal (Liu et al., 2021). Another risk factor in the same category is parental depression. Children’s mental health is significantly affected by that of parents (Adams & Emerson, 2020). Marin et al. (2019) determined that parents’ stress, depression, and psychological control levels significantly predicted children’s school refusal levels.

In the environmental risk factor category for school refusal, the code of being from different cultures and being in a minority position draws attention. Rosenthal et al. (2020) investigated the experiences of immigrant parents of adolescents who were diagnosed with school refusal. In particular, social inequalities or exposure to racism were found to be the main challenges for these parents. In addition, parents may experience feelings of guilt because their children’s future has been interrupted since they migrated, which may open the door to issues such as parenting stress and depression.

The second component of school refusal is school refusal symptoms. It was found that students who experience school refusal in this category tend to show high levels of aggression, have unpleasant feelings towards school (Devenney & O’Toole, 2021), have inadequate parent-child interactions (Gallé-Tessonneau & Heyne, 2020), have insufficient peer interaction (Gallé-Tessonneau & Heyne, 2020; Filippello et al., 2018), absenteeism, intolerance to classroom time, and avoidance of school (Gallé-Tessonneau & Heyne, 2020). Behaviors generally observed among children with school refusal are defined by Kearney (2007) as physical problems, such as non-specific anxiety or worrying that something bad will happen, tension from being around others, or having to perform, general sadness of having to go to school, irritability and restlessness, stomachache, headache, tremor, nausea, vomiting, frequent urination, muscle tension, diarrhea, lightheadedness or fainting, palpitations, dizziness, shortness of breath, hyperventilation, sweating, and tantrums, such as insomnia, extreme tiredness, crying, screaming, kicking, and shaking.

The third component of school refusal is a protective factor against school refusal. In this context, protective factors are discussed as protective factors originating from individual, family, and environmental characteristics. In particular, examining the protective factors arising from individual characteristics, high level of social functioning, high self-esteem, and learning goals stand out as protective factors. From this aspect, it can be said that students with high social functioning and prosocial behaviors (Filippello et al., 2018), academic resilience (Seçer & Ulaş, 2020), and self-esteem can eliminate several risk factors for school refusal.

In this study, codes related to protective factors arising from environmental factors were positive teacher-student relations, perception of teacher support, and early intervention in psychiatric problems. Brandseth et al. (2019) concluded that belonging to the classroom mediated teacher support and mental well-being. This is considered an important protective factor for school refusal, according to studies examining the predictive relationships between school attachment and school refusal (Seçer & Ulaş, 2020).

Another category within the protective factors was determined to be the protective factors arising from family characteristics. In this context, children’s perceptions of family harmony and family functioning emerged as codes with an important protective function for school refusal. Gonzálvez et al., (2019) concluded in their study that it is important to solve family problems in order to prevent school refusal. In a study carried out with adolescents with and without school refusal, parenting self-efficacy perceptions of parents of adolescents with school refusal were lower than those of parents of adolescents without school refusal (Carless et al., 2015). Since parental self-efficacy perceptions of parents are an important determinant of family functioning, it can be concluded that high-level family functioning perception has a protective role against school refusal. In addition, studies have shown that the relationship between parents and children, in other words, healthy attachment patterns, have an essential protective function against school refusal (Doobay, 2008).

Another component of school refusal was found to be the consequences of school refusal. The codes were low school attachment, low academic achievement, emotional distress, social withdrawal, and depression. On the other hand, Sewell (2008) listed the consequences of school refusal as low academic achievement in the short term (less than two years), negative peer and family relationships, academic failure in the long term (more than two years), and psychiatric problems. School refusal results in mental health problems, especially anxiety and depression (Devenney & O’Toole, 2021). Social withdrawal, the consequence of school refusal, and a symptom of depression have also been frequently discussed in the literature. Social withdrawal and low social functioning (Seçer & Ulaş, 2020) are consequences of school refusal. With the decrease in school attachment, the problem of school refusal can lead to early school dropout, which is more broadly defined as perpetuating not going to school without an excuse (Awad-Abouzid et al., 2021). School dropouts can cause serious sociological problems as well as mental health problems.

As a result of the discussion on the risk and protective factors, symptoms, and consequences of school refusal, it was found that there is a problem that necessitates early intervention. In this context, the last theme of the study was determined to be the intervention approaches and techniques addressing the school refusal. In this sense, it includes parenting counseling (Strömbeck et al., 2021), CBT, school-based rapid return approach (Maeda & Heyne, 2019), time-out technique, and inclusion of trauma intervention techniques as a recommendation in school curricula (Devenney & O’Toole, 2021) were the codes determined. CBT-based interventions were intense in the studies included in the scope of the study (Strömbeck et al., 2021). In studies on anxiety as a risk factor for school refusal, it was reported that there was a decrease in school refusal behaviors and an increase in school attendance with CBT-based interventions in children with anxiety (Doobay, 2008; Thastum et al., 2019) and depression.

Gradual muscle relaxation, modeling, exposure, cognitive restructuring, social skills, problem-solving, and coping skills were emphasized, and it was concluded that it was effective in the intervention of school refusal (Doobay, 2008). It was suggested that parents should be involved in the intervention for a realistic and lasting impact on school refusal (Doobay, 2008). In particular, the inclusion of sessions and modules in CBT programs for parents was frequently preferred, and it was concluded to be effective (Reissner et al., 2015). Behavioral interventions for school refusal mainly use techniques such as exposure, systematic desensitization (including relaxation training), guided affective imagery, modeling, and shaping (Elliott & Place, 2012). However, some therapists may abstain from using exposure because they think that it can be dangerous (Richard & Gloster, 2007), increase school refusal (Gryczkowski et al., 2013), and negatively affect the therapeutic alliance (Kendall et al., 2009). However, Peterman et al. (2015) provided a handy guide to exposure techniques in response to school refusal resulting from avoiding anxiety-provoking situations.

Nuttall and Woods (2013) aimed to deal with school refusal by using an ecological approach. Richardson (2016), on the other hand, used the family therapy approach to intervene with school refusal in children and adolescents. The results showed that systemic family therapy for the treatment of school refusal tends to be significantly effective in younger children when the problem is not fully established and family functioning is high before problematic behavior.

In line with the findings and literature, school refusal can be considered a problem that needs to be prevented and intervened. The consequences of school refusal in the short term cause situations such as decreased academic success, social withdrawal and isolation, increased risk of legal problems such as juvenile delinquency, conflict within the family, and changes in the daily life routines of the family and the individual; in the long term, it cause situations such as dropping out of school, economic deprivation, social, and can cause professional and marital problems, alcohol or substance addiction, crime, and mental impairment (Kearney et al., 2007). School attendance problems due to school refusal can lead to a decrease in school success, a weakening of social relationships, a decrease in school belonging, and, ultimately, school dropout. This situation is undoubtedly a stress factor for the family, which limits the family functionality between parents and other children. Parents may feel that they have made mistakes while raising their children, are inadequate, or are blamed by the school staff (Havik et al., 2014). Given this situation, which significantly limits the level of social welfare, this study provides both practical and theoretical contributions in developing collaborative multifaceted applications and enabling education politicians to focus on the importance of this issue. By understanding school refusal conceptually and addressing the basic risk and protective factors, it can be evaluated that this study has a facilitating role in creating e-courses, training modules, and psychoeducational contents for students, parents, teachers, and education policymakers.

Future direction

The present study provided recommendations for both researchers and practitioners. It was determined that there is a limited number of randomized controlled trials regarding school refusal (Heyne et al., 2011; Maynard et al., 2015). As a result of this situation, it was observed that there is a limitation in evidence-based interventions for school refusal. At this point, it is suggested that future researchers should focus on randomized controlled trials regarding school refusal. In addition to standard therapy approaches in randomized controlled studies (such as Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Psychodynamic Therapy), it is recommended to develop problem-specific programs or modules based on the adaptations of these therapies (Elliott & Place, 2018). Furthermore, the findings suggest studies to be carried out in accordance with the mixed-methods approach, which combines the advantages of both quantitative and qualitative methods, resulting in research with high validity and reliability (Mertens, 2023). In addition, the need for multi-level studies is emphasized, and it is recommended to carry out these studies cross-culturally in order to achieve generalizable results.

For practitioners such as educational policymakers, school psychologists, and other experts, it is suggested that they can expand the content of educational programs by making use of the findings of this study, which addresses school refusal as a multifaceted problem with a defined framework. Considering the fact that school attendance problems can lead to individual as well as social issues, these adjustments can be considered necessary. Moreover, it is recommended that parents and school staff also participate in various practices such as training or courses in a comprehensive approach. Indeed, in the present study, collaboration between schools and families, as well as positive teacher-child relationships, were identified as protective factors (Filippello et al., 2019). Furthermore, considering that immigrant children, those with developmental problems, and children with various health issues carry risks of school refusal, it is suggested that preventive and intervention programs addressing these groups should be promoted.

Limitations

The fact that only the keyword “school refusal” was used as a keyword in the search process is a limitation. Although WoS is accepted as the most important database in the international scientific literature (Harzing & Alakangas, 2016), the fact that other databases were not searched is also a limitation of this study. The inclusion and exclusion criteria (being accessible with the “school refusal” keyword in WoS, being published between 2012 and 2021, being open access, and being published in the English language) for data sources can also be considered as a limitation. As a result of the search made with the keyword “school refusal” in the Web of Science database, it was seen that the studies carried out in the last 10 years (2022 − 2012) constituted 51% of the total. Considering that the first publication year was 1970, the reason for this limitation is to reach more up-to-date school refusal studies. In addition, more publications with 51% are the source of this study. Although publications were made in Russian (1%), German (1%), French (0.6%), and Japanese (0.3%), etc. languages, the publication language of the data sources was limited to English. The reason for this is that 95% of the publications are published in English. In this context, it is recommended to carry out studies that eliminate these limitations in future review studies on school refusal.

Data availability

The datasets for this study can be found in this link. (https://drive.google.com/file/d/1hkC4zvxMJpuPgUooq-gW0PzHrWaSsOEK/view?usp=share_link)

References

Adams, D., & Emerson, L. (2020). The impact of anxiety in children on the autism spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51, 1090–1920. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04673-3

Awad-Abouzid, A., El-Ganzory, S., G., & Said Sayed, F. (2021). Psychosocial program for primary school student to overcome school refusal behavior. Journal of Nursing Science Benha University, 2(2), 273–287. https://doi.org/10.21608/JNSBU.2021.186465

Benarous, X., Guedj, M. J., Cravero, C., Jakubowicz, B., Brunelle, J., Suzuki, K., & Cohen, D. (2022). Examining the hikikomori syndrome in a French sample of hospitalized adolescents with severe social withdrawal and school refusal behavior. Transcultural Psychiatry, 59(6), 831–843. https://doi.org/10.1177/13634615221111633

Bitsika, V., Heyne, D. A., & Sharpley, C. F. (2021). Is bullying associated with emerging school refusal in autistic boys? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(4), 1081–1092. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04610-4

Bitsika, V., Sharpley, C., & Heyne, D. (2022). Risk for school refusal among autistic boys bullied at school: Investigating associations with social phobia and separation anxiety. International Journal of Disability Development and Education, 69(1), 190–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2021.1969544

Brandseth, O. L., Håvarstein, M. T., Urke, H. B., Haug, E., & Larsen, T. (2019). Mental well-being among students in Norwegian upper secondary schools: The role of teacher support and class belonging. Norsk Epidemiologi, 28(1–2). https://doi.org/10.5324/nje.v28i1-2.3050

Carless, B., Melvin, G. A., Tonge, B. J., & Newman, L. K. (2015). The role of parental self-efficacy in adolescent school-refusal. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(2), 162–170. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000050

Chu, B. C., Rizvi, S. L., Zendegui, E. A., & Bonavitacola, L. (2015). Dialectical behavior therapy for school refusal: Treatment development and incorporation of web-based coaching. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(3), 317–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.08.002

Delgado, B., Martínez-Monteagudo, M. C., Ruiz-Esteban, C., & Rubio, E. (2019). Latent class analysis of school refusal behavior and its relationship with cyberbullying during adolescence. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1916. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01916

Devenney, R., & O’Toole, C. (2021). “What kind of education system are we offering”: The views of education professionals on school refusal. International Journal of Educational Psychology, 10(1), 27–47. https://doi.org/10.17583/ijep.2021.7304

Doobay, A. F. (2008). School refusal behavior associated with separation anxiety disorder: A cognitive-behavioral approach to treatment. Psychology in the Schools, 45(4), 261–272. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20299

Elliott, J. G., & Place, M. (2012). Children in difficulty: A guide to understanding and helping. Routledge.

Elliott, J. G., & Place, M. (2018). Practitioner review: School refusal: Developments in conceptualisation and treatment since 2000. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(1), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12848

Elliott, S., & Gainor, J. (2023). School refusal: A case-based exploration of school avoidance. The Brown University Child and Adolescent Behavior Letter, 39(9), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbl.30731

Fernández-Sogorb, A., Gonzálvez, C., & Pino-Juste, M. (2022). Understanding school refusal behavior in adolescence: Risk profiles and attributional style for academic results. Revista De PsicodidáCtica (English ed), 28(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psicoe.2022.12.001

Filippello, P., Sorrenti, L., Buzzai, C., & Costa, S. (2018). Predicting risk of school refusal: Examining the incremental role of trait EI beyond personality and emotion regulation. Psihologija, 51(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.2298/PSI170526013F

Filippello, P., Buzzai, C., Costa, S., & Sorrenti, L. (2019). School refusal and absenteeism: Perception of teacher behaviors, psychological basic needs, and academic achievement. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1471. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01471

Filippello, P., Buzzai, C., Messina, G., Mafodda, A. V., & Sorrenti, L. (2020). School refusal in students with low academic performances and specific learning disorder. The role of self-esteem and perceived parental psychological control. International Journal of Disability Development and Education, 67(6), 592–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2019.1626006

Fremont, W. P. (2003). School refusal in children and adolescents. American Family Physician, 68(8), 1555–1560. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2003/1015/afp20031015p1555.pdf. Accessed 05.05.2023

Fujita, J., Aoyama, K., Saigusa, Y., Miyazaki, H., Aoki, Y., Asanuma, K., Takahashi, Y., & Hishimoto, A. (2022). Problematic internet use and daily difficulties among adolescents with school refusal behaviors: An observational cross-sectional analytical study. Medicine, 101(7), e28916. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000028916

Gallé-Tessonneau, M., & Heyne, D. (2020). Behind the SCREEN: Identifying school refusal themes and sub-themes. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 25(2), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2020.1733309

Gonzálvez, C., Díaz-Herrero, Á., Sanmartín, R., Vicent, M., Pérez-Sánchez, A. M., & García-Fernández, J. M. (2019). Identifying risk profiles of school refusal behavior: Differences in social anxiety and family functioning among Spanish adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(19), 3731. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193731

Gonzálvez, C., Giménez-Miralles, M., Vicent, M., Sanmartín, R., Quiles, M. J., & García-Fernández, J. M. (2021a). School refusal behaviour profiles and academic self-attributions in language and literature. Sustainability, 13(13), 7512. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137512

Gonzálvez, C., Martín, M., Vicent, M., & Sanmartín, R. (2021b). School refusal behavior and aggression in Spanish adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 669438. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.669438

Gonzálvez, C., Díaz-Herrero, Á., Vicent, M., Sanmartín, R., Aparicio-Flores, P., M., & García-Fernández, J. M. (2023). Typologies of Spanish Youth with School Refusal Behavior and their relationship with aggression. Journal of Aggression Maltreatment & Trauma, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2023.2234840

Gryczkowski, M. R., Tiede, M. S., Dammann, J. E., Jacobsen, A., Hale, L. R., & Whiteside, S. H. (2013). The timing of exposure in clinic-based treatment for childhood anxiety disorders. Behavior Modification, 37, 211–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445512456546

Harzing, A. W., & Alakangas, S. (2016). Google scholar, scopus and the web of Science: A longitudinal and cross-disciplinary comparison. Scientometrics, 106, 787–804. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1798-9

Havik, T., Bru, E., & Ertesvåg, S. K. (2014). Parental perspectives of the role of school factors in school refusal. Emotional Behav Difficulties, 19(2), 131–153.

Havik, T., Bru, E., & Ertesvåg, S. K. (2015). School factors associated with school refusal- and truancy-related reasons for school non-attendance. Social Psychology of Education, 18, 221–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-015-9293-y

Heyne, D. (2019). Developments in classification, identification, and intervention for school refusal and other attendance problems: Introduction to the special series. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 26(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2018.12.003

Heyne, D., & Boon, A. E. (2023). School refusal in adolescence: Personality traits and their influence on treatment outcome. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1177/10634266231151903

Heyne, D. A., & Sauter, F. M. (2013). School refusal. In C. A. Essau & T. H. Ollendick (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of the treatment of childhood and adolescent anxiety (pp. 471–517). John Wiley and Sons Limited.

Heyne, D., Sauter, F. M., Van Widenfelt, B. M., Vermeiren, R., & Westenberg, P. M. (2011). School refusal and anxiety in adolescence: Non-randomized trial of a developmentally sensitive cognitive behavioral therapy. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25(7), 870–878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.04.006

Heyne, D., Strömbeck, J., Alanko, K., Bergström, M., & Ulriksen, R. (2020). A scoping review of constructs measured following intervention for school refusal: Are we measuring up? Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1744. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01744

Higgins, J. P., & Green, S. (2008). Guide to the contents of a Cochrane protocol and review. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: Cochrane Book Series (pp. 51–79). https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470712184.ch4

Inglés, C. J., Gonzálvez-Maciá, C., García-Fernández, J. M., Vicent, M., & Martínez-Monteagudo, M. C. (2015). Current status of research on school refusal. European Journal of Education and Psychology, 8(1), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejeps.2015.10.005

Ingul, J. M., & Nordahl, H. M. (2013). Anxiety as a risk factor for school absenteeism: What differentiates anxious school attenders from non-attenders? Annals of General Psychiatry, 12(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-859X-12-25

Ingul, J. M., Havik, T., & Heyne, D. (2019). Emerging school refusal: A school-based framework for identifying early signs and risk factors. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 26(1), 46–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2018.03.005

Karthika, G., & Devi, M. G. (2020). School refusal - psychosocial distress or psychiatric disorder? Telangana Journal of Psychiatry, 6(1), 14–18. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.tjp.2020.005

Kearney, C. A. (2007). Getting your child to say yes to school: A guide for parents of youth with school refusal behavior. Oxford University Press.

Kearney, C. A. (2008). School absenteeism and school refusal behavior in youth: A contemporary review. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(3), 451–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.012

Kearney, C. A., & Albano, A. M. (2004). The functional profiles of school refusal behavior: Diagnostic aspects. Behavior Modification, 28(1), 147–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445503259263

Kearney, C. A., Chapman, G., & Cook, L. C. (2005). School refusal behavior in young children. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy, 1(3), 216–222. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0100746

Kearney, C. A., Cook, L. C., & Chapman, G. (2007). School stress and school refusal behavior. In G. Fink (Ed.), Encyclopedia of stress (2nd ed., vol. 3, pp. 422–425). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012373947-6.00337-8

Kendall, P. C., Comer, J. S., Marker, C. D., Creed, T. A., Puliafico, A. C., Hughes, A. A., & Hudson, J. (2009). In-session exposure tasks and therapeutic alliance across the treatment of childhood anxiety disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(3), 517–525. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013686

Leduc, K., Tougas, A. M., Robert, V., et al. (2022). School refusal in youth: A systematic review of ecological factors. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-022-01469-7

Li, A., Guessoum, S. B., Ibrahim, N., Lefèvre, H., Moro, M. R., & Benoit, L. (2021). A systematic review of somatic symptoms in school refusal. Psychosomatic Medicine, 83(7), 715–723. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000956

Liu, L., Gu, H., Zhao, X., & Wang, Y. (2021). What contributes to the development and maintenance of school refusal in chinese adolescents: A qualitative study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 782605. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.782605

Maeda, N., & Heyne, D. (2019). Rapid return for school refusal: A school-based approach applied with Japanese adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2862. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02862

Maeda, T., Oniki, K., & Miike, T. (2019). Sleep education in primary school prevents future school refusal behavior. Pediatrics International, 61(10), 1036–1042. https://doi.org/10.1111/ped.13976

Marin, C. E., Anderson, T., Lebowitz, E. R., & Silverman, W. K. (2019). Parental predictors of school attendance difficulties in children referred to an anxiety disorders clinic. European Journal of Education and Psychology, 12(1), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.30552/ejep.v12i1.239

Maynard, B. R., Brendel, K. E., Bulanda, J. J., Heyne, D., Thompson, A. M., & Pigott, T. D. (2014). Psychosocial interventions for school refusal with primary and secondary school students: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 11(1), 1–76. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2015.12

Maynard, B. R., Heyne, D., Brendel, K. E., Bulanda, J. J., Thompson, A. M., & Pigott, T. D. (2015). Treatment for school refusal among children and adolescents. Research on Social Work Practice. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731515598619

Mertens, D. M. (2023). Research and evaluation in education and psychology: Integrating diversity with quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods. Sage.

Munkhaugen, E. K., Gjevik, E., Pripp, A. H., Sponheim, E., & Diseth, T. H. (2017). School refusal behaviour: Are children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder at a higher risk? Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 41–42, 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2017.07.001

Nayak, A., Sangoi, B., & Nachane, H. (2018). School refusal behavior in Indian children: Analysis of clinical profile, psychopathology and development of a best-fit risk assessment model. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 85(12), 1073–1078. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-018-2631-2

Niec, L. N. (Ed.). (2018). Handbook of parent-child interaction therapy: Innovations and applications for research and practice. Springer.

Nuttall, C., & Woods, K. (2013). Effective intervention for school refusal behaviour. Educational Psychology in Practice, 29(4), 347–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2013.846848

Nwosu, K. C., Wahl, W. P., Nwikpo, M. N., Hickman, G. P., Ezeonwunmelu, V. U., & Akuneme, C. C. (2022). School refusal behaviours profiles among Nigerian adolescents: Differences in risk and protective psychosocial factors. Current Psychology, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03890-6

Ochi, M., Kawabe, K., Ochi, S., Miyama, T., Horiuchi, F., & Ueno, S. I. (2020). School refusal and bullying in children with autism spectrum disorder. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 14, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-020-00325-7

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery, 88, 105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

Peterman, J. S., Read, K. L., Wei, C., & Kendall, P. C. (2015). The art of exposure: Putting science into practice. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(3), 379–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.02.003

Reissner, V., Jost, D., Krahn, U., Knollmann, M., Weschenfelder, A., Neumann, A., ..., Hebebrand, J. (2015). The treatment of school avoidance in children and adolescents with psychiatric illness: A randomized controlled trial. Deutsches Arzteblatt International, 112(39), 655–662. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2015.0655

Richard, D. C. S., & Gloster, A. T. (2007). Exposure therapy has a public relations problem: A dearth of litigation amid a wealth of concern. In D. C. S. Richard & D. Lauterbach (Eds.), In Comprehensive handbook of the exposure therapies (pp. 409–425). Academic.

Richardson, K. (2016). Family therapy for child and adolescent school refusal. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 37(4), 528–546. https://doi.org/10.1002/anzf.1188

Rocque, M., Jennings, W. G., Pquero, A. R., Ozkan, T., & Farrington, D. P. (2017). The importance of school attendance: Findings from the Cambridge study in delinquent development on the life-course effects of truancy. Crime and Delinquency, 63(5), 592–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128716660520

Rosenthal, L., Moro, M. R., & Benoit, L. (2020). Migrant parents of adolescents with school refusal: A qualitative study of parental distress and cultural barriers in access to care. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 942. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00942

Roué, A., Harf, A., Benoit, L., Sibeoni, J., & Moro, M. R. (2021). Multifamily therapy for adolescents with school refusal: Perspectives of the adolescents and their parents. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 624841. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.624841

Seçer, İ, & Ulaş, S. (2020). The mediator role of academic resilience in the relationship of anxiety sensitivity, social and adaptive functioning, and school refusal with school attachment in high school students. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 557. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00557

Sewell, J. (2008). School refusal. Australian Family Physician, 37(6), 406. Obtained from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.563.5265&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Accessed 05.05.2023

Strömbeck, J., Palmér, R., Lax, S., Fäldt, I., Karlberg, J., M., & Bergström, M. (2021). Outcome of a multi-modal CBT-based treatment program for chronic school refusal. Global Pediatric Health. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333794X211002952

Tekin, I., & Aydın, S. (2022). School refusal and anxiety among children and adolescents: A systematic scoping review. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2022(185–186), 43–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20484

Thastum, M., Johnsen, D. B., Silverman, W. K., Jeppesen, P., Heyne, D. A., & Lomholt, J. J. (2019). The Back2School modular cognitive behavioral intervention for youths with problematic school absenteeism: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 20(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-018-3124-3

Ulaş, S. (2022). The adaptation of parent-child interaction therapy into Turkish culture and the examination of its effectiveness on children with autism, children with typical development, and their parents. (Doctoral Dissertation), Atatürk University, Erzurum, Türkiye. https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalTezMerkezi/TezGoster?key=kScA8XnrRb0WogX-qPGFklw43djRrRRYbwHxHCLmxdWKyEc-iVbZ5X9Bko8aP2ef. Accessed 01.07.2023

Ulaş, S., & Seçer, İ. (2022). Developing a CBT-based intervention program for reducing school burnout and investigating its effectiveness with mixed methods research. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 884912. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.884912

Zawacki-Richter, O., Kerres, M., Bedenlier, S., Bond, M., & Buntins, K. (2020). Systematic reviews in educational research: Methodology, perspectives and application. Springer Nature.

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK). This article was produced from the project process named “Design, Creation, and Development of the Scientific Observatory for School Attendance” supported by the code “KA220-SCH-5C779D81” funded by the European Union.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, S.U.; methodology, S.U.; software, S.U.; validation, İ. S.; formal analysis, S.U., İ.S.; investigation, İ.S., S.U.; writing—original draft preparation, S.U.; writing—review and editing, S.U, İ.S.; illustrations, S.U.; supervision, İ. S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

We have no funds for this study. Figures 1 and 2 used in the text are entirely the work of the authors. It has not been citations anywhere.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(MX20 17.3 MB)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ulaş, S., Seçer, İ. A systematic review of school refusal. Curr Psychol 43, 19407–19422 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05742-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05742-x