Abstract

Informational failures frequently lead consumers to make non-optimal energy-efficient purchasing decisions. Energy efficiency labels seek to influence consumer behaviour at the point of sale by reducing informational failures regarding energy efficiency. However, several informational and behavioural factors contribute to the energy efficiency gap and could render label-oriented policies useless. The purchasing decision model of Allcott and Greenstone (The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26, 3–28, 2012) is used here to explore the different factors that influence purchasing decisions and understand (i) the importance of energy consumption compared to other attributes; (ii) how consumers weight energy savings and (iii) what other benefits and costs influence the purchase of energy-efficient goods. The analysis reported here is based on qualitative research methods and is conducted in the household and service sectors (the accommodation sector and private service companies), for appliances, heating and cooling systems and cars in Spain. Results show that (i) there is still an informational gap regarding energy labels and (ii) bounded rationality and end-user behaviour are important limiting factors for the purchase of energy-efficient goods in Spain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The European Commission is seeking to increase the energy efficiency (EE) of energy-related products as a means of achieving energy savings of at least 32.5% by 2030 (European Commission 2014). Evidence has shown, however, that although EE may have a number of economic and environmental benefits (e.g. cost reductions, decreases in carbon and other emissions), many households and businesses invest less in it than what would appear to be economically rational, while others make EE investments which do not seem to be financially worthwhile (Gerarden et al. 2017; Jaffe et al. 2004; Linares and Labandeira 2010).

One explanation for this can be found in the intertemporal arbitrage problem that consumers solve when deciding whether to make an investment involving present and future costs. For instance, consumers often fail to account for running costs during the life cycle of a product and heavily discount future energy savings (Train 1985) or undervalue future savings (Allcott and Wozny 2013). This is an expression of the so-called energy efficiency gap or energy efficiency paradox (Jaffe and Stavins 1994). There are other possible explanations for this paradox which are usually grouped under the headings of market failures (including informational failures) and behavioural failures (Gerarden et al. 2017; Linares and Labandeira 2010; Ramos et al. 2015).

Informational failures are one of the most frequent type of failures in the energy market. They lead consumers to make non-optimal choices (Allcott and Sweeney 2016; Phillips 2012). Many policy measures have been proposed and explored for addressing failures of this type, including information campaigns, fiscal incentives, feedback tools, audits and certificates or labels (Newell and Siikamäki 2014; Ramos et al. 2015; Waechter et al. 2015). Energy labels are commonly used to address informational failures as they are easy and cheap to implement (Ramos et al. 2015).

Energy labelling in the European Union (EU) dates back more than 25 years: it was first implemented in 1994 for appliances in the application of Directive (1992/75/ECC) and extended to cars in 1999 with Directive (1999/94/EC). Energy labels are designed to highlight the EE of a good and consequently reduce the information gap (Carroll et al. 2016; Lucas and Galarraga 2015). They provide information on the energy consumption of an energy-related product, on its use of other resources (such as water) and on comfort levels (e.g. noise).

The content of labels varies from one product and sector to another. For some products, colour-based labels are used while for others, labels report technical information. The EU Energy Labelling Directive (2010/30/EU) for household appliances requires energy labels to be displayed on energy-related appliances at the point of sale with a scale that ranges from A+++ (the most efficient) to D (the least efficient) using different colours.Footnote 1 The heating and cooling industry is covered by two types of regulation: the Ecodesign Regulation and the Energy Labelling Regulation. The latest Ecodesign Regulation, published in 2016,Footnote 2 summarises the most relevant information on energy performance, EE and the emission of nitrogen oxides from air heating and cooling products, high-temperature process chillers and fan coil units. Most of these heating and cooling products are also covered by energy labelling regulationsFootnote 3 and use technical labels. Under the Labelling Directive for cars, two types of label are used in EU countries: a compulsory label, which must provide information on CO2 emissions (g/km) and fuel consumption (L/100 km), and a voluntary label which provides the same information but with a coloured alphabetical (A-G) grid. The voluntary label is not currently applied in Spain.

There is a growing body of research on how to improve EE labels so as to encourage energy-efficient purchases by providing running cost information (Carroll et al. 2016; Codagnone et al. 2016; Kallbekken et al. 2013), health or environment-related information (Asensio and Delmas 2016) or by improving the design of labels to take behavioural failures into account (Waechter et al. 2016). However, other informational and behavioural factors are also likely to mark down the role of these labels. Failing to control for those factors would mean that efforts to improve labelling scheme would be merely scratching the surface.

This paper seeks to provide some qualitative insights into the factors that influence consumers’ purchasing decisions in regard to energy-efficient goods. The analysis is supported by the purchasing decision model of Allcott and Greenstone (2012), in which purchasing decisions are driven by three sets of factors: (i) the difference in energy intensity of goods; (ii) unobserved costs and benefits and (iii) various weightings representing consumers’ preferences, attitudes and behaviour that mark down the weight of EE in purchasing decisions. Goods are assumed to differ only in their energy intensity. However, in a market, there are attributes other than energy intensity which can create differences between energy durable goods and they may be more highly rated by consumers than EE attributes. Consumers may thus prefer a non-energy-efficient good for attributes other than energy intensity. Failing to identify such non-energy-related attributes and possible weighting factors can result in an overestimation of the role of energy savings in the EE gap.

The paper sets out to answer three main questions associated with the key parameters of the purchasing decision model of Allcott and Greenstone (2012): (i) do consumers focus only on energy intensity differences when purchasing energy durable goods or are there other attributes that they are likely to rate more highly than EE? (ii) How do consumers weight energy savings? (iii) What are the unobserved costs and benefits of energy-efficient goods? A common qualitative methodology is used to address these questions in different sectors (and products) in order to highlight potential differences between them.

The analysis focuses on the household, services and transport sectors in Spain, which between them account for about 75% of the country’s energy consumption (IDAE 2017). EE provides an opportunity to reduce energy consumption in the household sector (Linares and Labandeira 2010; Ramos et al. 2015) and in the accommodation and transport sectors (Schleich 2009; Schlomann and Schleich 2015) and to reduce energy-related running costs in the services sector (Patel and Guedes 2017; Sakshi et al. 2020).

The products under review account for a significant proportion of energy consumption in Spain.Footnote 4 Specifically, they are (i) household appliances; (ii) heating, ventilation and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems and appliances for accommodation owners and (iii) cars for private companies with their own fleet.

Two qualitative research methods are used to capture experiences in the different sectors and products: focus group discussion and in-depth interviews. Specifically, one focus group and sixteen in-depth interviews were carried out in Spain between May and July 2017 to collect qualitative data from the household and services sectors (accommodation sector and private services companies), respectively.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows: the “Methodology” section presents the decision model used and the qualitative methodology applied. The “Results” section reports the main results for the three specific research questions raised. The “Discussion” section discusses the main results and the “Conclusion” section concludes.

Methodology

Theoretical framework of investment decisions

Energy-efficient investment decisions are intertemporal decisions: in the initial period, the consumer chooses the capital investment; then, in the second period, the consumer uses the good and incurs the energy cost. The investment decision model of the seminal paper of Allcott and Greenstone (2012), which allows to explain why investments in energy efficiency with positive financial returns are not realised, is used to structure the decision-making of consumers regarding energy-efficient purchases. This investment model has been widely used for identifying factors limiting energy efficiency investments and test ways to reduce information asymmetry, for transport (Brazil et al. 2019) or appliances (Damigos et al. 2020; Filippini et al. 2020) among other goods. The model considers a profit/utility maximising agent who has to decide between an energy-efficient good with an energy intensityFootnote 5e1 and an energy inefficient good with an energy intensity of e0 > e1. The two goods are assumed to differ only in their energy intensity levels. The agent, i, then chooses the energy-efficient investment if

where p is the price of a unit of energy, mi is the agent-specific quantity of energy services and 푟 is the risk-adjusted discount rate. ε represents the unobserved costs or benefits that influence the utility function and c the incremental investment costs of the more efficient good. γ is a weighting parameter which captures investment inefficiencies when γ < 1.

Focus group and in-depth interviews

A qualitative approach based on a focus group and in-depth interviews was used to address the research questions raised in the “Introduction” section. Focus group and in-depth interview methods (Milena et al. 2008; Starr 2014) were used in order to ascertain how EE was understood by consumers and what barriers they still faced when deciding the EE level of energy-related purchases. These methods are particularly well suited to understanding the practices, opinions and expectations of different consumers regarding EE and EE labels. They are equally well suited to exploring consumers’ perceptions and preferences without imposing the restrictions of a quantitative approach where predefined statements are usually proposed to the participant or interviewee, with the risk of their not being the most relevant to that particular consumer. They also enable a common framework analysis to be used for all sectors. However, this approach can hurt the robustness required for policy recommendations. This qualitative research thus complements the more quantitative studies reported in the literature with a view to providing a better understanding of all the dimensions of EE knowledge and the case of Spain in particular. Participants for both focus group and in-depth interviews were recruited by a market research company that collects market and consumer information in Spain.

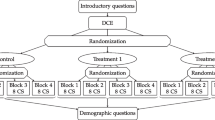

Focus group

A focus group was designed to analyse consumers’ preferences regarding household appliances, specifically refrigerators and washing machines.Footnote 6 The focus group discussion was conducted on May 31, 2017, in the city of Bilbao with a total of 8 participants. It lasted around 2 h. Participants were recruited strategically to represent typical households in Spain in terms of gender, education level (low, medium, high), age, number of homes (1 or 2), household composition (number of members) and socio-economic status (low, medium, high). The characteristics of each participant are presented in Appendix 1 (Table 3). At the end of the discussion, they were paid €25 for participating.

A diversified composition of the focus group was preferred to a repetition of several differentiated focus groups. The fact that only one focus group was carried out may hurt the robustness of the results but running a second or third focus group with participants with the same diversified profiles would have added very little value to the qualitative findings. Moreover, the goal was not to test for differences between differentiated groups of participants but rather to analyse the attitudes and opinions of typical households in Spain. According to Krueger and Casey (2008), it can be argued that different focus groups may lead to relatively different findings but for qualitative analysis, it is well documented that the most important factors can be covered in one well-structured focus group.

In-depth interviews

In total, 16 in-depth interviews were conducted face-to-face in Spain to analyse the cases of appliances and HVAC systems (among accommodation owners) and vehicles (at service sector companies with their own vehicle fleets). Initially, 8 IDIs were held in Spain between June 21, 2017, and July 5, 2017, for different types of accommodation establishments including cottages, hotels, hostels and guesthouses, to analyse their decision-making processes in purchasing appliancesFootnote 7 and HVAC.Footnote 8 The 8 accommodation owners were recruited so as to provide a representative sample of climate areas (warm and cool), geographical locations (north and Mediterranean), types of area (urban, mountain and coast), types of accommodation (cottage, guesthouse, hostel, hotel) and other accommodation establishment characteristics (star rating, number of rooms, occupancy rate). Details of the sample are provided in Table 4 in Appendix 1.

Eight further IDIs were later held in and around Bilbao concerning car fleet purchasing decisions in the private services sector. This sample comprised small (4 companies with 3 vehicles), medium (2 companies with 11 and 18 vehicles) and large fleets (2 companies with 120 and 515 vehicles). The companies interviewed include building renovation firms, driving schools, construction companies and others (see Table 5 of Appendix 1 for more details of the sample).

The total number of interviews conducted is within the normal range used to identify the most relevant views of respondents through open-ended questioning (Guion et al. 2001; Milena et al. 2008; Styśko-Kunkowska 2014).

Discussion guidelines

In-depth interviews were preferred to focus groups in the private service sector because of the availability constraint on bringing together executives from the sector for a focus group meeting. However, the focus group and the sixteen in-depth interviews followed common discussion guidelines with four areas (see Appendix 2). First, the context of the purchasing decision was established for each sector and product (who was responsible for purchasing decisions and what the purchasing process was); then, the first main area involved identifying the key attributes that influenced decision-making for purchasing in the different product categories analysed (e.g. “What are the key factors in the purchasing decision?” “Do you consider EE in the purchasing decision?”). In the focus group for appliances, the group was asked to consensually weight the main attributes and explain the relative importance of each one in the purchasing decision.Footnote 9

The second area focused on the comprehension of EE. Consumers’ understanding of EE (e.g. “Do you understand what EE is?” “What do you mean by EE?”) and their reasons for buying more energy-efficient products (and barriers in the way of such purchases) (e.g. “Why should you buy a high energy-efficient product (and why not)?”) were addressed. In the focus group for household appliances, a role play was staged in which participants were separated into two gender-balanced groups: one group was asked to list arguments in favour of buying an energy-efficient appliance (e.g. an A+++-labelled fridge) and the other arguments for not doing so (e.g. a D-labelled fridge). A group leader reported the arguments and a group discussion followed, with counter-arguments.In the third area, focus group and in-depth interview participants were asked about their knowledge and understanding of energy labels (e.g. “Are you familiar with the label?” “Do you think it is useful and clear?”). The fourth and final area sought to analyse how labels could be improved (e.g. “How could labelling be improved?” “What should be added/replaced/changed?”). Indicating running costs in monetary terms was discussed as a specific proposal for improving the understanding of EE labels and therefore encouraging energy-efficient purchases (e.g. “What do you think about providing energy consumption data in monetary units?” “Would you appreciate it?”). Both the focus group and the in-depth interviews were recorded on audio and transcribed to text. The information collected was assessed at a macro-level in search of participant consensus, patterns and general themes. This process is known as content analysis (Elo and Kyngäs 2008; Hsieh and Shannon 2005).

Results

The results reported here hinge on the three sets of main elements of the decision model presented in the theoretical framework (Theoretical framework of investment decisions) and answer the following questions: (i) do consumers focus only on differences in energy intensity when purchasing energy durable goods or are there other attributes likely to be more highly rated than energy? (ii) How do consumers weight energy savings? (iii) What are the unobserved costs and benefits of energy-efficient goods?

The importance of energy intensity and other attributes

EE is rated differently in the three sectors and is not generally the biggest driving factor. For household buying refrigerators, there were different opinions regarding the role of attributes such as dimensions, capacity and price in the actual decision-making process. Some participants attributed more weight to dimensions and capacity (which it was agreed to treat jointly), whereas others put more on price. In the end, a consensus was reached to rank both in joint first place with the same weighting. Another consensus had to be reached between brand and energy consumption.Footnote 10 It was finally agreed to rank the energy consumption attribute in second place. Third place went to a generic category jointly representing performance, safety and aesthetics.Footnote 11 And, fourth place went to brand. The same exercise was carried out for washing machines with similar results, though in this case, participants attached more importance to load capacity than to price, followed by performance,Footnote 12 dimensions and brand in that order.

When accommodation owners were asked about the factors that influenced their purchasing decisions with respect to new appliances, the attribute most frequently mentioned was price, followed by a brand in terms of value for money, durability and customers’ perceptions. Capacity and noise level (decibels) were also mentioned, particularly for mini-bars in hotel rooms. Other attributes such as shape and size, aesthetics (shape, colour, etc.) and the performance of appliances (particularly TVs) were also mentioned. EE was found to be less important and was mentioned spontaneously by just three of the eight interviewees in relation to kitchen appliances, mini-bars and hair dryers.For HVAC, constraining factors such as budget and the infrastructure of hotels were mentioned, given that once hotels initially install HVAC, it is very costly and difficult to renew and adapt the system to the infrastructure of the hotel. Brand was the most important factor, related mainly to durability (resistance) and technical and maintenance support and then came other characteristics such as size and energy consumption.

The decision to purchase vehicles for car fleets in the private service sector was seen as a two-stage process: first, certain initial requirements were identified (for instance capacity, volume, number of seats, etc.) as necessary for the intended purposes of vehicles; then, a set of final attributes drove the decision. These final attributes seemed to be driven by an intertemporal arbitrage of cost minimisation, communication, safety and comfort attributes. Communication and safety-related attributes included communication between the driver, the company and the customers. Connectivity to a global positioning system and Bluetooth cell phone was mentioned as helping to reduce transport/delivery times and deal with customers while maintaining safety and security standards. These attributes and air-conditioning were also associated with comfort.

The intertemporal arbitrage of cost minimisation in this case consisted of balancing the future running costs implied by energy consumption (and maintenance) against the purchasing price. The price of vehicles and their energy consumption are the attributes that the interviewees immediately referred to. Vehicle brand seemed to attract less interest: the person responsible for purchasing cars usually compares several brands and chooses those that best balance these attributes. Companies also give importance to the robustness of vehicles so as to reduce the likelihood of unexpected maintenance expenses and reduce future running costs.

EE seems not to be the first attribute in the purchasing decision in any of the three sectors analysed. In the best case, it ranks second (refrigerators) and in the worst, it is not mentioned at all (most accommodation establishments in regard to the purchase of appliances).

Consumer weighting of energy savings

Lack of information is an important factor that leads consumers not to purchase energy-efficient goods (Allcott and Greenstone 2012). This factor can be seen in different forms in all three sectors (see Table 1). First, in all sectors, participants mentioned that they were unable to calculate the savings or that it would take them too long to do so. Private companies were able to calculate the savings to compare conventional fuel vehicles but were unable to estimate the energy costs of electric/hybrid vehicles. The lack of experience with hybrid/electric cars limits their ability to determine whether investing in such vehicles would result in net gains or net losses compared to fossil fuel vehicles.

A principal-agent problem limits the perception of the benefits obtained from energy-efficient goods, particularly in the accommodation sector and in the private sector for companies with car fleets. Customers of accommodation establishments are not willing to pay more for an energy-efficient service as they cannot observe the level of efficiency, particularly regarding HVAC. Owners are thus not willing to buy such goods since the payback period on the investment may be longer if the price of the room does not increase. Fleet vehicles are owned by a company and operated by employees who do not pay the costs of ownership and use (maintenance and fuel). The company (the principal) wishes to minimise those costs but the employee (the agent) has no incentive to conserve fuel. Users and buyers differ in their incentives, so a usage problem results (Graus and Worrell 2008) and the company is unlikely to buy a more expensive but energy-efficient vehicle. To deal with this principal-agent issue, companies monitor consumption by assessing consumption individually per kilometre. However, none of the companies contacted kept strict controls. Rather, they only checked in detail when excessive expenditure was detected: “I control things more or less. I check where they have been during the month, what they should have consumed and what they actually consumed, and if the figures are normal and logical that’s the end of the matter. However, if it [consumption] has risen sharply I ask them what happened”, said one interviewee from a private company. Accommodation establishments face a similar end-user problem. They seek to control energy consumption in different ways: by turning off radiators in empty rooms, informing customers face-to-face or by posters, using automatic card systems in rooms and installing remote controls.

Several sources of uncertainty are also observed which tend to mark down the importance of EE in the purchasing decision. In all three sectors, participants said that they mistrusted the information on consumption given on the label and suspected that actual consumption was higher. Households expressed a similar opinion regarding the useful lifetimes of appliances. They felt that the actual useful lifetime was likely to be shorter than the official one. They were thus reluctant to buy more expensive appliances that could last less than indicated.

Uncertainty as to future electricity price stability is another factor that affects the perceived profitability of an investment and potentially the purchasing decision: to quote one respondent, “I think there would be more gain [referring to investment in an electric or hybrid vehicleFootnote 13], right? Though it’s probably just like for everything else: they’ll probably raise the price of electricity afterwards. There has to be a catch somewhere”. Similar reasoning emerged in other sectors. Consumers believed that future increases in the price of electricity, particularly for users who switched energy source, would mark down their budget equilibrium as they already had to support the initial investment in EE. Surprisingly, they associate the regulation of the energy market with the market for energy durable goods and do not realise that if the price of energy increases running costs will be lower with more energy-efficient goods. A bidding budget constraint may support this reasoning, particularly for those consumers that cannot bear both an (observed or anticipated) increase in energy price and a higher initial price of the good. Consumers with a bidding budget constraint and who anticipate higher energy price prefer to allocate their budget to the running cost than to the initial investment cost.

Unobserved costs and benefits of energy-efficient purchases

Participants from all three sectors had a vague understanding of the concept of EE. They connected it with ideas such as energy production, the reduction of energy consumption and the existence of a label (in the case of households). Even in the case of car fleets, companies were concerned about the fuel consumption of cars but did not relate this to the concept of EE. In spite of this fuzzy understanding, all were aware that the reduction in energy consumption from energy-efficient goods came at the expense of a higher purchasing price.

All the participants from the different sectors referred to a number of hard-to-measure associated benefits or costs that would also influence their purchasing decision (see Table 2). All agreed that purchasing energy-efficient goods would benefit the environment and help mitigate climate change. In private service companies, lower demand for fuel, gas and electricity would reduce the environmental impact from resource extraction and energy production. However, environmental awareness was mentioned by only two of the eight companies: “I’m concerned [about environmental protection] and I think in that sense the fundamental limitation is the choice of fuel”. For others, “this [CO2 emissions] is a detail that we have never worried about”. Additionally, households and accommodation owners were found to be aware that the associated reduction in pollution would benefit public health.

Contributing to the green economy was also mentioned by households and accommodation owners as a co-benefit of the purchase of energy-efficient goods. Their purchase was thus seen as contributing to the creation of new jobs and to research and development.

For interviewees whose work entailed direct contact with customers, such as accommodation establishments and private service companies, energy-efficient cars or appliances were seen as helping to green their image, convey the message that they were a company with environmental concerns and were technologically up-to-date; they were also seen as enhancing their reputation in the sector.

In addition to the observed higher cost of purchase, participants referred to other, less tangible costs that nonetheless affected their final decisions. These were cited mostly by accommodation owners and private companies with car fleets. The maintenance cost of more energy-efficient appliances was perceived to be higher due to the use of new technologies whose repair and maintenance were perceived as more expensive, particularly in HVAC. Given the limited range and long charging times of electric cars, concern was expressed that purchasing them would generate costs in the form of lost market opportunities and delays in delivering merchandise that would hurt the reputation of the company. The limited number of charging points would also require a reorganisation of car parking areas during non-office hours. Employees would have to leave the cars they use in the company car park to recharge them. This would result in additional commuting time which could reduce both the productivity and well-being of workers. The limited supply of electric vehicles was another limiting factors for companies; few models per brand are equipped with electric engines and fewer match their needs. Meanwhile, they have to use conventional vehicles with higher energy-related running costs.

Discussion

There are several factors that help explain the EE gap in the household, accommodation and private sectors in Spain regarding appliances, HVAC and vehicles. The results reported here show that EE is a secondary rather than a key primary attribute in purchasing decisions. Informational failures still seem to exist regarding EE 25 years after the implementation of labels. Energy labels seem not able to convey to consumers in understandable units of measurement how much they would save if they bought energy-efficient products. This is particularly the case for goods that consume electricity: appliances, HVAC and electric vehicles.Cognitive bias as a form of bounded rationality was also highlighted in the analysis. Consumers are frequently unable to process the information required to trade-off alternatives in real decision-making processes (Blasch et al. 2019; Kahneman 1994). An inability to calculate energy costs or the energy saved by buying a more energy-efficient good was revealed in all three sectors. In an exercise during the focus group and in-depth interviews, participants were shown official energy labels and asked about their knowledge and understanding of them as well and how they would modify them so that they helped in making informed purchases. In all three sectors, consumers recognised that the colour-based label was an appropriate signal of energy performance which provided more information than technical labels (currently used for cars in Spain). For vehicles, participants felt that using the voluntary colour-based label would also harmonise the use of labels in the car industry since it is similar to that used for car parts such as tyres. However, the unit of measurement in this case is also difficult to understand for non-experts.

Ways to improve labels by changing their design and contents to make them more understandable and thus, encourage energy-efficient purchases were discussed. The information provided on energy consumption in kilowatt per year for appliances and HVAC was not fully clear to non-experts. The idea of indicating running cost in monetary terms was discussed as a way to overcome this knowledge gap. Several challenges in regard to providing monetary estimates were raised because of the uncertainty related to both consumption per annum and electricity prices. A monetary running cost depends on the frequency of use, which may differ from one consumer to another, and on the market price of energy. Households suggested that information could be presented for an average number of uses and for an average electricity price. For car buyers, knowing how much on average could be saved with the most efficient vehicle compared to a less efficient one would be useful. The interviewees suggested that this information could be reported on the basis of the average distance travelled in kilometres per year since the payback time of an investment in an energy-efficient vehicle depends significantly on its use and the lifetime considered.

This hypothesis of providing additional monetary information on the label has been tested experimentally and hypothetically in the literature and has been shown to have a potentially positive effect on energy-related purchases for appliances (Allcott and Sweeney 2016; Newell and Siikamäki 2014; Stadelmann and Schubert 2018) and for vehicles (Allcott and Knittel 2019). However, the lifetime used to report the running costs of energy-related products is a critical element that seems to influence the effectiveness of this measure. Participants in the focus group and in-depth interviews differed concerning the choice of lifetimes for reporting running costs. In the household sector, there was support for reporting the costs per use of washing machines (i.e. on an hourly basis), whereas, in the service sector, reporting running costs of vehicles per annum was preferred. Min et al. (2014) show that providing information for long periods (lifetime of light bulbs) would have more impact on purchasing decisions than giving annual information. Further research seems to be required to reach a consensus on how monetary information should be shown on EE labels.

Even when energy savings are expressed in monetary terms, consumers apply a number of weighting factors to potential savings. The principal-agent problem seems to be the main market failure that influences EE choices which is found in all three sectors studied here (households, accommodation establishments and private transport). It arises when one party makes a decision but another party bears the cost or enjoys the benefits of that decision (Gillingham and Palmer 2014; Phillips 2012). This intrinsically relates to end-user behaviour. The split incentive is a particular principal-agent problem where the incentives of the parties are different. It is particularly the case of relationships between landlords (agents) and tenants (principals) (Bird and Hernández 2012; Gillingham and Palmer 2014) and between car fleet users (agents) and buyers (principals) (Graus and Worrell 2008), whose incentives for investing in EE differ. The results reported here show that accommodation establishments and companies with car fleets are reluctant to invest in EE because they cannot fully control end-user behaviour. This issue was also raised by households regarding the use of appliances, particularly by households with children, where there may be difficulties in controlling the use of appliances.

Consumers who face a principal-agent problem also relate purchases to their budget constraints: they prefer to spend their budget on paying electricity bills (and anticipated future increases in energy prices) than incur the additional cost of buying energy-efficient goods since they suspect that consumption will not actually decrease due to end-user behaviour.

Uncertainty is a special circumstance or factor that could make consumers more likely to use heuristics and underestimate the importance of energy savings. Under uncertainty, the rationality of decision-making leads consumers to think in terms of expected payoffs and they are likely to derive utility from gains and losses relative to a reference point rather than in absolute terms (Kahneman 1994; Kahneman and Tversky 1979). The lack of experience with energy-efficient vehicles such as hybrid or electric and uncertainty as to future energy prices was mentioned frequently in the interviews as reasons for being unable to assess the profitability of investing in such vehicles. As shown by Greene (2011), uncertainty about energy prices combined with loss aversion on the part of buyers results in decision-making bias. Estimating the profitability of investing in EE vehicles is a difficult and time-consuming task for companies. When it is furthermore subject to a certain mistrust in consumption information, it becomes difficult to draw up an ex ante balance of the extra cost of the purchase and the future flow of energy costs. Using heuristics may thus be less costly and less time-consuming.

Conclusion

Reducing the energy efficiency gap is a critical step towards achieving the goals of cutting energy consumption and reducing CO2 emissions. This paper explores the factors that motivate consumers to purchase energy-efficient goods across different sectors (households, the accommodation sector and private services companies) in Spain. Based on the purchasing decision model of Allcott and Greenstone (2012), it analyses how highly consumers rate energy savings, how they weight them and how unobserved costs and benefits influence the decision whether to purchase energy-related goods. A qualitative approach based on focus groups and in-depth interviews is used to address those questions. This method is particularly suitable for exploring consumers’ perceptions and identifying important factors which may not show up in deductive quantitative inquiries alone and highlighting concepts that can be developed and tested using quantitative methods in larger samples. The results indicate that the difference in energy intensity between goods is not the most significant attribute in the purchasing decision for all types of agents. There are several barriers and unobserved costs, especially in the case of electric vehicles. Energy-efficient purchases are also affected by a number of unobserved benefits related to the environment and human health. These are potential arguments for promoting energy-efficient purchases. Few differences are observed across agents (households, accommodation owners and private companies with car fleets) and products (appliances, heating, ventilation and air-conditioning and cars).

Bounded rationality and the principal-agent problem through end-user behaviour are the most relevant obstacles (weights) for the purchase of energy-efficient products. Consumers generally do not understand the unit of measurement of energy consumption shown on energy labels. Providing additional information in monetary terms is technically challenging but would reduce this knowledge gap according to participants. However, reducing informational failure by adding monetary information to labels is likely to clash with end-user behaviour that behaviour often cannot be controlled at a reasonable cost: it renders consumers (households or companies) unwilling to pay the higher purchasing price for energy-efficient products. In addition to informational instruments for effective labels, other instruments are needed to reduce the weights assigned by consumers to energy savings: instruments that help overcome the issues of bounded rationality and end-user behaviour.

Notes

A recasting of the Energy Labelling Directive for household appliances was accepted in January 2017. The proposed regulation would restore the original A to G energy label scale by March 1st 2021, according to the EU Energy Labelling Directive (2019/2016).

Commission Regulation (EU) 2016/2281 of 30 November 2016 implementing Directive 2009/125/EC.

Energy Labelling Regulation (EU) No 626/2011 for air conditioners, Energy Labelling Regulation (EU) No 811/2013 for space heaters and combination heaters, Energy Labelling Regulation (EU) 2015/1186 for local space heaters, Energy Labelling Regulation (EU) 2015/1187 for solid fuel boilers.

More detailed information can be found in ODYSSEE-MURE project.

Energy intensity can be thought of as the energy used by one unit of energy services, e.g. kilowatt per hour of lighting or litres of fuel per kilometre of driving.

For refrigerators, potential energy savings come mainly at the EE level, while for washing machines, the use seems to be more effective.

The appliances analysed were (i) appliances in rooms such as TV sets, mini-bars, coffee-makers and hair-dryers and (ii) appliances in general use such as washing machines, fridges, ovens and dishwashers.

Only three of the eight accommodation establishments had air-conditioning, but all had heating systems (one had a heat pump, another a gas stove and the rest oil or gas boilers).

After an open discussion, a table showing different attributes that may be featured when buying a refrigerator and a washing machine was distributed to the focus group participants. They were asked to select (and order) the top five. The results were put together on a blackboard (with the factors selected scored in order of importance from 5 to 1 by each participant and then added to provide overall scores) and a common hierarchy for the whole group was established. Based on that common hierarchy, the group consensually weighted the most relevant factors that resulted from the ranking, distributing 100% of the purchasing decision.

Female participants placed rated the brand of refrigerators more highly, for instance, whereas men tended not to take it into account.

Performance refers to no-frost system and number of trays; safety to open door alarm and aesthetics to colour, material and design.

Understood as number and functions of programmes, control panel, spin speed, water overflow control, water consumption, energy consumption.

To ascertain the perception of company owners about gains and losses from uncertain investment, interviewees were asked the following question: “Do you think that with the purchase of a high energy-efficiency vehicle (electric, hybrid) your company might: (a) gain more than it could lose (why?); (b) lose more than it could gain (why?) and (c) you may be unable to distinguish between expected gains (energy savings) and expected losses (why?)”.

References

Allcott, H., & Greenstone, M. (2012). Is there an energy efficiency gap? The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26, 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.26.1.3.

Allcott, H., & Knittel, C. (2019). Are consumers poorly informed about fuel economy? Evidence from Two Experiments. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 11, 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20170019.

Allcott, H., & Sweeney, R. L. (2016). The role of sales agents in information disclosure: Evidence from a field experiment. Management Science, 63, 21–39. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2015.2327.

Allcott, H., & Wozny, N. (2013). Gasoline prices, fuel economy, and the energy paradox. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 96, 779–795. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00419.

Asensio, O. I., & Delmas, M. A. (2016). The dynamics of behavior change: Evidence from energy conservation. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 126(Part A), 196–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2016.03.012.

Bird, S., & Hernández, D. (2012). Policy options for the split incentive: Increasing energy efficiency for low-income renters. Energy Policy, Special Section: Frontiers of Sustainability, 48, 506–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2012.05.053.

Blasch, J., Filippini, M., & Kumar, N. (2019). Boundedly rational consumers, energy and investment literacy, and the display of information on household appliances. Resource and Energy Economics, 56, 39–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reseneeco.2017.06.001.

Brazil, W., Kallbekken, S., Sælen, H., & Carroll, J. (2019). The role of fuel cost information in new car sales. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 74, 93–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2019.07.022.

Carroll, J., Denny, E., & Lyons, S. (2016). The effects of energy cost labelling on appliance purchasing decisions: Trial results from Ireland. Journal of Consumer Policy, 39, 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-015-9306-4.

Codagnone, C., Veltri, G. A., Bogliacino, F., Lupiáñez-Villanueva, F., Gaskell, G., Ivchenko, A., Ortoleva, P., & Mureddu, F. (2016). Labels as nudges? An experimental study of car eco-labels. Economics and Politics, 33, 403–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-016-0042-2.

Damigos, D., Kontogianni, A., Tourkolias, C., & Skourtos, M. (2020). Behind the scenes: Why are energy efficient home appliances such a hard sell? Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 158, 104761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104761.

Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62, 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x.

European Commission. (2014). 2030 Energy Strategy - Energy - European Commission [WWW Document]. Energy. https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/strategies/2030_en. Accessed 11-22-17.

Filippini, M., Kumar, N., & Srinivasan, S. (2020). Energy-related financial literacy and bounded rationality in appliance replacement attitudes: Evidence from Nepal. Environment and Development Economics, 25, 399–422. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X20000078.

Gerarden, T. D., Newell, R. G., & Stavins, R. N. (2017). Assessing the energy-efficiency gap. Journal of Economic Literature, 55, 1486–1525. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20161360.

Gillingham, K., & Palmer, K. (2014). Bridging the energy efficiency gap: Policy insights from economic theory and empirical evidence. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, 8, 18–38. https://doi.org/10.1093/reep/ret021.

Graus, W., & Worrell, E. (2008). The principal-agent problem and transport energy use: Case study of company lease cars in the Netherlands. Energy Policy, 36, 3745–3753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2008.07.005.

Greene, D. L. (2011). Uncertainty, loss aversion, and markets for energy efficiency. Energy Economics, Special Issue on The Economics of Technologies to Combat Global Warming, 33, 608–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2010.08.009.

Guion, L., Diehl, D., McDonald, D. (2001). Conducting an in-depth interview. University of Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences: EDIS.

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15, 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

IDAE, 2017. Informe sintético de indicadores de eficiencia energética en España.

Jaffe, A., & Stavins, R. (1994). The energy-efficiency gap. What does it mean? Energy Policy, Markets for Energy Efficiency, 22, 804–810. https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-4215(94)90138-4.

Jaffe, A., Newell, R., & Stavins, R. (2004). Economics of energy efficiency. Encyclopedia of Energy, 2, 79–90.

Kahneman, D. (1994). New challenges to the rationality assumption. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (JITE) / Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswissenschaft, 150, 18–36.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263–291. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185.

Kallbekken, S., Sælen, H., & Hermansen, E. A. T. (2013). Bridging the energy efficiency gap: A field experiment on lifetime energy costs and household appliances. Journal of Consumer Policy, 36, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-012-9211-z.

Krueger, R.A., Casey, M.A., (2008). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research, Edición: Fourth Edition. ed. SAGE Publications, Inc, Los Angeles.

Linares, P., & Labandeira, X. (2010). Energy efficiency: Economics and policy. Journal of Economic Surveys, 24, 573–592. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6419.2009.00609.x.

Lucas, J., & Galarraga, I. (2015). Green Energy Labelling. In Green Energy and Efficiency, Green Energy and Technology (pp. 133–164). Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-03632-8_6.

Milena, Z. R., Grundey, D., & Stancu, A. (2008). Qualitative research methods: A comparison between focus-group and in-depth interview. Annals of Faculty of Economics, 4, 1279–1283.

Min, J., Azevedo, I.L., Michalek, J. & de Bruin, W.B. (2014). Labeling energy cost on light bulbs lowers implicit discount rates. Ecological Economics, 97, 42–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.10.015.

Newell, R. G., & Siikamäki, J. (2014). Nudging energy efficiency behavior: The role of information labels. Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists, 1, 555–598. https://doi.org/10.1086/679281.

Patel, P. C., & Guedes, M. J. (2017). Surviving the recession with efficiency improvements: The case of hospitality firms in Portugal. International Journal of Tourism Research, 19, 594–604. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2132.

Phillips, Y. (2012). Landlords versus tenants: Information asymmetry and mismatched preferences for home energy efficiency. Energy Policy, 45, 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2012.01.067.

Ramos, A., Gago, A., Labandeira, X., & Linares, P. (2015). The role of information for energy efficiency in the residential sector. Energy Economics, Frontiers in the Economics of Energy Efficiency, 52(Supplement 1), S17–S29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2015.08.022.

Sakshi, S., Cerchione, R., & Bansal, H. (2020). Measuring the impact of sustainability policy and practices in tourism and hospitality industry. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29, 1109–1126. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2420.

Schleich, J. (2009). Barriers to energy efficiency: A comparison across the German commercial and services sector. Ecological Economics, Methodological Advancements in the Footprint Analysis, 68, 2150–2159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.02.008.

Schlomann, B., & Schleich, J. (2015). Adoption of low-cost energy efficiency measures in the tertiary sector—An empirical analysis based on energy survey data. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 43, 1127–1133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2014.11.089.

Stadelmann, M., & Schubert, R. (2018). How do different designs of energy labels influence purchases of household appliances? A field study in Switzerland. Ecological Economics, 144, 112–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.07.031.

Starr, M. A. (2014). Qualitative and mixed-methods research in economics: Surprising growth, promising future. Journal of Economic Surveys, 28, 238–264. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12004.

Styśko-Kunkowska, M. (2014). Interviews as a qualitative research method in management and economics sciences. Warsaw: Warsaw School of Economics.

Train, K. (1985). Discount rates in consumers’ energy-related decisions: A review of the literature. Energy, 10, 1243–1253. https://doi.org/10.1016/0360-5442(85)90135-5.

Waechter, S., Sütterlin, B., & Siegrist, M. (2015). The misleading effect of energy efficiency information on perceived energy friendliness of electric goods. Journal of Cleaner Production, 93, 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.01.011.

Waechter, S., Sütterlin, B., Borghoff, J., & Siegrist, M. (2016). Letters, signs, and colors: How the display of energy-efficiency information influences consumer assessments of products. Energy Research and Social Science, 15, 86–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2016.03.022.

Acknowledgements

This work was undertaken as a part of the CONSumer Energy Efficiency Decision making (CONSEED) project, an EU-funded H2020 research project under grant agreement number 723741. This research is also supported by the Spanish State Research Agency through María de Maeztu Excellence Unit accreditation 2018-2022 (Ref. MDM-2017-0714).

Funding

Amaia de Ayala would like to thank the financial support of Fundación Ramón Areces under the project entitled “La toma de decisiones de los hogares en eficiencia energética: determinantes y diseño de políticas”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Consumer energy efficiency decision making across sectors

Article Collection Editor: Eleanor Denny, Department of Economics, Trinity College Dublin, the University of Dublin

Appendices

Appendix 1. Sample characteristics

Appendix 2. Common discussion guidelines across sectors and goods

The in-depth interviews and the focus group used the following general guidelines. Specific questions for each sector and product category were drawn up for each general question (available on request).

-

Context of the purchasing decision

-

Who is responsible for making the decision to purchase products?

-

How is the purchasing process organised?

-

What steps are taken, how much time is invested?

-

Where do you usually buy the product?

-

-

-

Exploring significant parameters of choice

-

What are the key factors in the purchasing decision?

-

Do you consider energy efficiency in the purchasing decision?

-

-

Energy efficiency awareness/comprehension

-

What is energy efficiency?

-

Do you understand it? Do you trust it?

-

Why do you take it into account when buying a new product (or why not)?

-

Do you care about the energy consumption of products? How do you show this?

-

Why would you buy an energy-efficient product? What are the main barriers to doing so?

-

-

Assessment of current energy labels

-

How do you get information about the efficiency level of products?

-

Are you familiar with the labelling system for products? Do you understand it? Do you think it is useful and clear?

-

-

Exploring changes in labels

-

Do you think the information displayed on labels could be improved?

-

How could labelling be improved?

-

What should be removed?

-

What should be added?

-

What should be changed?

-

-

What do you think about providing energy consumption data in monetary units (either to supplement or to replace the physical unit of kWh/year)?

-

Would you appreciate this?

-

Do you think it is useful?

-

-

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Ayala, A., Foudi, S., Solà, M. et al. Consumers’ preferences regarding energy efficiency: a qualitative analysis based on the household and services sectors in Spain. Energy Efficiency 14, 3 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12053-020-09921-0

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12053-020-09921-0