Abstract

Metal components made by additive manufacturing have large inherent surface roughness, and, as such, their strength and fatigue life can be reduced significantly versus wrought products. In order to improve these properties, a novel mechanical surface treatment that introduces compressive residual stress while simultaneously reducing the surface roughness is proposed. The proposed treatment uses cavitation peening combined with an abrasive slurry. The impact of the kinetic energy-charged abrasive particles, induced by collapsing water cavitation vapor bubbles, produces compressive residual stress, while the abrasive reduces the surface roughness. Plane-bending fatigue tests were carried out to determine the effectiveness of this treatment on the fatigue life and strength of titanium alloy Ti6Al4V manufactured by electron beam melting. It was demonstrated that the fatigue strength of an as-built specimen was improved from 169 MPa to 280 MPa by the proposed treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Additive manufacturing (AM) such as electron beam powder bed melting (EBPB) and laser beam melting (LBM) are attractive processes for the aerospace and biomedical industries, as complex metal components can be produced directly using computer-aided design systems, and “near-net-shape” manufacturing with shorter lead times and reduced material waste can be achieved.1,2 However, the fatigue life and strength of components manufactured by AM can be very small and also variable due to the surface roughness,1,3,4 One method that has been reported to improve the fatigue strength of titanium alloy Ti6Al4V manufactured by EBPB is shot peening, which introduces compressive residual stress into the surface.1 However, to reduce the surface roughness of AM metal components, further surface treatment is needed.

Chan et al. have reported that the fatigue life of titanium alloy Ti6Al4V manufactured by EBPB and LBM, including rolled and cast specimens, is proportional to the maximum surface roughness.4 Rafi et al. and Gong et al. studied the effect of defects on the mechanical properties of Ti6Al4V fabricated by EBPB and LBM 5,6; however, their specimens were machined or ground. Furthermore, Seifi et al. carried out a review of the flaws found in metal specimens made by AM, such as voids, layer defects and inclusions, and also the porosity.7 The effects of surface roughness, however, were not discussed. As is well known, AM metals have large inherent surface roughness due to powder. Fousova et al. discussed the influence of the surface roughness and internal defects on the fatigue properties of Ti6Al4V manufactured by EBPB and selective laser melting (SLM), and concluded that the surface roughness is the most critical property.8 Thus, investigations into the effect of surface roughness on the fatigue performance of AM Ti6Al4V have been investigated by many research groups,9,10,11,12,13,–14 and several processes to be performed during and after AM have been proposed.15

Edwards and Ramulu, et al. showed that the fatigue strength of Ti6Al4V manufactured by EBPB and SLM in various stacking directions could be improved by machining and shot peening.1,9 Improvements in the fatigue strength of Ti6Al4V manufactured by AM by milling were confirmed by Sato et al. and Bagehorn et al.11,16 Machining and milling can reduce roughness of the surface; however, it is very difficult to apply these processes to the inner walls of components or undercut structures. Other methods used to improve the quality of the surface are chemical polishing17 and laser polishing18,19; however, neither of these methods introduce compressive residual stress into the surface. One of key factors determining the fatigue properties of AM Ti6Al4V is residual stress; 9 thus, as well as polishing, the introduction of compressive residual stress is very important. A typical method used to introduce compressive residual stress is shot peening. Unfortunately, this produces sparks and dust, and it has been pointed out that these could lead to dust explosions.20 Also, the contact made between the shot and the metal being treated can cause material to be transferred to the surface, and there is a risk that this might become the source of corrosion. In order to avoid this risk and to enhance the peening intensity, shotless peening such as laser peening21,22 and cavitation peening,23,24 have been proposed. Compressive residual stress can be introduced into the surface of AM Ti6Al4V by cavitation peening and laser peening,16,25 and these processes have been shown to improve the fatigue strength of Ti6Al4V manufactured by EBM.26 The great advantage of cavitation peening is that it can be used to treat undercut parts and the internal walls of holes,27,28 as the cavitation bubbles can get into these regions before the bubbles collapse. In a previous study, we demonstrated that the fatigue strength of Ti6Al4V manufactured by EBPB was improved by 84% by cavitation peening; however, the surface roughness of the treated specimen was similar to that of an as-built specimen.26 Thus, a process that combines the introduction of compressive residual stress by cavitation peening with a process that reduces the surface roughness should improve the fatigue properties.

In this paper, we propose a novel surface finishing method that uses an abrasive cavitating jet, which reduces the surface roughness by abrasion while simultaneously introducing compressive residual stress by cavitation peening. Zhang et al. have reported that EBPB can produce components with higher densities compared with SLM,29 and Chan et al. examined the relationship between the fatigue life and the surface roughness of AM Ti6Al4V manufactured both by EBPB and LBM. Once improvements in the fatigue properties of EBPB metals have been demonstrated, these can be applied to other AM metals. In the present experiment, specimens made by EBPB were treated with an abrasive cavitating jet, and the fatigue life and strength were evaluated using plane-bending fatigue tests. The residual stress and the hardness of the surface of the specimens were also measured as well as the surface roughness.

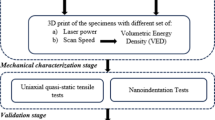

Experimental Facilities and Procedures

The geometry of the specimens used for the plane-bending fatigue tests was the same as in the previous report.26 The thickness of the specimens was 2 ± 0.2 mm and all were manufactured by EBPB. The powder used in the EBPB process was Ti6Al4V with an average diameter of about 75 μm. The diameter of the spot size in the EBPB process was 0.2 mm and the stacking pitch was 90 μm. The stacking direction was in the width direction of the specimen. The width of the specimen at the center was 20 mm with a radius of curvature of 45 mm. The specimens were heat-treated at 1208 K under vacuum for 105 min, then cooled in argon gas. Then, aging was carried out at 978 K under vacuum for 2 h before the specimens were cooled in argon gas. After that, the edges of all the specimens were polished by hand using rubber whetstones of #80 and #180, to reduce crack initiation from the edges, as described in a previous report.26

Figure 1 shows a schematic diagram of the abrasive cavitating jet apparatus. Filtered tap water in tank B is pressurized by a plunger pump with an intensifier, and this is injected via a nozzle into the water-filled tank A, where the abrasives are introduced into the cloud of imploding cavitation bubbles and become charged with kinetic energy. The abrasive medium used was alumina particles with a diameter of about 50 μm. The injection pressure of the jet was set to 62 MPa (9000 psi). The length l and diameter d of the nozzle were 2 mm and 0.64 mm, respectively. The nozzle has an outlet bore downstream from the throat of the nozzle to increase the aggressive intensity of the cavitation jet. The diameter D and the length L of the outlet bore were chosen to be in the ratio d:D:L = 1:8:8 following results obtained from a previous study.30 The specimen is fixed to the base in tank A using a holder cut in the shape of the specimen in order to make a flat surface so that cavitation develops on the surface. The nozzle is actuated by a linear X–Y stage at scanning speed v in the length direction of the specimen. The x direction was the horizontal direction, as shown in Fig. 1, and the y direction was the other horizontal direction which was the orthogonal direction to x. The processing time per unit length t is defined by Eq. 1:

where n is the number of scans. In this study, the specimens were treated by the abrasive cavitating jet at v = 18 mm/s with n set at 1, 2, 3 and 4. After each set of n scans, the nozzle was moved 1.2 mm sideways. As the length of the specimens was 90 mm, the processing time, tp, was 5 s, 10 s, 15 s and 20 s for n = 1, 2, 3 and 4, respectively.

The standoff distance s is defined by the distance from the nozzle to the specimen surface. In the case of peening using a submerged high-speed water jet, there are two mechanisms, one is cavitation peening and the other is water jet peening. Note that cavitation impact is used in cavitation peening and water column impact is used in water jet peening. These peening mechanisms are distinguished by the relationship between the cavitation number σ which is defined by Eq. 2 and the standoff distance s, given by Eq. 3.24

Here, pJ is the injection pressure, and pd and pv are the downstream pressure and vapor pressure, respectively. For the experiments carried out in this study, pd was approximately atmospheric pressure and σ was about 0.0016 at pJ = 62 MPa. If s > 1.8 × 0.0016−0.6 × 0.64 = 54.8 mm, for which the cavitation peening is carried out,24 then, for treatment by the abrasive cavitating jet, s was chosen to be 65 mm in order that the compressive residual stress would be introduced by cavitation peening.

The fatigue strength of an untreated specimen and a specimen treated with the abrasive cavitating jet were evaluated using a conventional Schenk-type displacement controlled plane-bending fatigue tester at stress ratio R = − 1 which was defined by the ratio of maximum and minimum stress. The span length at the fixed point was 65 mm, and the test frequency was 12 Hz. First, in order to find the optimum processing time, we considered the results of a previous report,28 where the number of cycles to failure Nf at a constant bending stress σa = 330 MPa, Nf 330, was evaluated as a function of the processing time tp. The following procedure was used to determine the number of cycles to failure at σa = 330 MPa. It is assumed that the S–N curve for non-treated specimens, for which the number of cycles to failure is low, is described by Eq. 4, and that for treated specimens is described by Eq. 5, where c1, c2 and c3 are constants. Thus, these S–N curves are parallel to each other:

Here, subscripts NT and T are non-treated and treated specimens, respectively. Thus, Nf 330 can be calculated from:

In this experiment, c1 and c2 were obtained from 3 experimental data points for the non-treated specimens by the method of least squares. The c3 was obtained from c1 and the experimental data points, i.e., σaT and NfT, for each specimen treated for the different processing times using Eq. 5.

Rearranging Eq. 6, we get:

From Eq. 7, we obtain Nf 330 for each processing time. In order to investigate the fatigue strength, fatigue tests were carried out for the optimum processing time that maximizes the fatigue life. The tests were terminated when 107 cycles were exceeded.

The fatigue strength of the specimens is affected primarily by both the surface roughness and the compressive surface/sub-surface residual stress. The arithmetic mean roughness Ra and the maximum height of the roughness Rz were measured by a profilometer with stylus cutoff lengths, λc, of 0.25 mm, 0.8 mm and 2.5 mm. As the surfaces of the specimens were very rough, the surface hardness was measured using a Rockwell superficial hardness tester. For the superficial hardness test, both a 120° diamond spheroconical indenter and a 1/16-inch-diameter (1.588 mm) steel sphere were used. The initial load was 3 kgf (29 N), and the applied load was 15 kgf (147 N). The hardness was measured seven times in each case, and the mean and standard deviation were obtained from all the values excluding the highest and lowest values. The thickness of material removed by the abrasive cavitating jet was measured by a caliper with a measurement accuracy of 0.01 mm.

The residual stress σR of the specimen surface was evaluated by a 2D method31 using x-ray diffraction with a two-dimensional detector. The x-ray diffraction patterns were obtained using Cu Kα x-rays from a tube operated at 40 kV and 40 mA through a 0.8-mm-diameter collimator with an incident monochromator. The lattice planes (h k l) used for these measurements were the Ti (2 1 3) and (3 0 2) planes, and the diffraction angles without strain were 139.5° and 148.4°, respectively. Using the conditions established in a previous study, 24 diffraction rings were measured at various angles.32 The exposure time per frame for locating the diffraction ring at each single position was 5 min.

Results

Figure 2 shows an image of a flat plate of Ti6Al4V coated with blue paint that has been treated by the abrasive cavitating jet. From this, we can identify the areas treated by the abrasive and the areas treated by cavitation impact. The 20-mm-wide region where the blue paint has been removed corresponds to the area treated by cavitation impact.33 As shown in Fig. 2, there are some spots outside the 20-mm band where the paint has been removed, showing that some large cavitation impact has occurred outside the band. The groove at the center has a width of about 2 mm, showing the area treated by the abrasive was about 2 mm. Thus, the nozzle was moved laterally in steps of 1.2 mm after each longitudinal scan.

In order to determine the optimum processing time for improving the fatigue properties, Fig. 3 shows the number of cycles to failure at σa = 330 MPa, i.e., Nf 330 as a function of processing time tp. Nf 330 for each tp was calculated using Eq. 7. In this study, c1 and c2 were found to be 199.58 and 1319.3, respectively. These values were obtained from the data for the untreated specimen at relatively high σa, i.e., Nf = 1.487 × 105 at σa = 293.7 MPa, Nf = 9.37 × 104 at σa = 329.9 MPa, and Nf = 6.22 × 104 at σa = 362.2 MPa. These three data points are shown in Fig. 6, which is described below. As shown in Fig. 3, Nf 330 = 9.36 × 104 for the untreated specimen, which is almost the same as the value, Nf 330 = 9.24 × 104, for the specimen with tp = 5 s. With tp = 10 s, Nf 330 has increased to 15.27 × 104, and reaches its maximum value with tp = 15 s, i.e., Nf 330 = 23.06 × 104. It then decreases at tp = 20 s. Thus, Nf 330 at tp = 15 s is about 2.5 times larger than that of the untreated one. Note that the thickness removed was 0.15 ± 0.03 mm at tp = 5 s, 0.23 ± 0.03 mm at tp = 10 s, 0.39 ± 0.03 mm at tp = 15 s and 0.42 ± 0.05 mm at tp = 20 s, as the process removed the specimen surface, showing that the fatigue life increases as material is abraded from surface. In order to understand the reason why Nf 330 has a peak at tp = 15 s, images of the specimens were examined.

Figure 4 shows images of Ti6Al4V specimens treated by the abrasive cavitating jet for various processing times. In Fig. 4, the stacking direction of EBPB is vertical. Many particles which have not fully melted can be seen on the surface of the untreated specimen. After treatment with tp = 5 s, most of the partially fused particles have been removed, but some still remain, and many deep valleys can be seen. This is why Nf 330 at tp = 5 s is nearly the same as Nf 330 for the untreated specimen in Fig. 3. With tp = 10 s, most of the deep valleys have been removed, but some indents which might be the remnants of the deep valleys are visible. With tp = 15 s, the indents have disappeared, and a wavy pattern is observed. With tp = 20 s, the wavy pattern has become deeper. It is clear that there are many particles on the surface before the treatment and that the surface becomes smoothest after a certain amount of processing time has been applied.

We carried out a quantitative evaluation of the effect of the processing time. Figure 5 shows (1) the arithmetical mean roughness, (2) the maximum height of the roughness, (3) the surface hardness and (4) the residual stress. Table I reveals data of the arithmetical mean roughness Ra and the maximum height of the roughness Rz at each processing time tp and the ratio between the roughness at tp= 0 s and 15 s. As shown in Fig. 5a and b, both Ra and Rz decrease for all cutoff lengths λc, reaching a minimum at tp = 15 s and then increasing. This is the main reason why Nf 330 has a maximum at tp = 15 s. The Ra and Rz were reduced by factors of approximately 8 with λc = 0.25 mm, 4 with λc = 0.8 mm and 2.5 with λc = 2.5 mm, after treatment. The surface hardness as a function of processing time is shown in Fig. 5c. Hardness measurements were made using a 120° diamond spheroconical indenter, HR15N, and a 1/16-inch-diameter (1.588 mm) steel sphere indenter, HR15T. Both measurements saturate after tp = 5 s with HR15T ≈ 90 and HR15N ≈ 75. The two measured hardness values of the untreated specimen were HR15T = 70 ± 3 and HR15N = 66 ± 7, showing that the surface hardness has improved by 14–28% after treatment. As shown in Fig. 5d, compressive residual stress is introduced by the abrasive cavitating jet, and this increases with tp and then saturates at tp ≈ 15 s with values of 220 MPa. The introduction of compressive residual stress is one reason why Nf 330 is improved by the abrasive cavitating jet.

Taking the results plotted in Fig. 3 into account, abrasive cavitating jet treatment for tp = 15 s was carried out on specimens which were then used in the plane-bending fatigue tester to obtain the fatigue strengths with and without treatment. Figure 6 shows the S–N curves of these specimens. For σa > 285 MPa, the S–N curve of the treated specimen has shifted to the right compared to the untreated one. Thus, the water abrasive cavitating jet and peening treatment has improved the fatigue life of the Ti6Al4V specimen. Using Little’s method,34 the fatigue strengths of the untreated and treated specimens were calculated to be 169 ± 8 MPa and 280 ± 10 MPa, respectively. That is, the abrasive cavitating jet and peening treatment improved the fatigue strength of Ti6Al4V manufactured by EBPB by 66%. Note that the fatigue strength of the wrought bar was 556 MPa.35

Discussion

In order to quantitatively evaluate the effect of the surface roughness, surface hardness and residual stress on the improvements made to the fatigue life after treatment with the abrasive cavitating jet, we show in Fig. 7 the relationship between the experimental data for the fatigue life Nf 330 exp and the estimated fatigue life Nf 330 est obtained from the surface roughness Rz′ with λc = 2.5 mm, the surface hardness HR15T′ and the compressive residual stress σCR measured from the diffraction patterns obtained using the (2 1 3) plane of Ti. The Rz′ and HR15T′ are the value of Rz and HR15T normalized by the untreated value. It is assumed that the compressive residual stress reduces the actual bending stress from σa to \( \left( {\sigma_{a} - a \cdot \sigma_{\text{CR}} } \right) \) . Here, a is constant with 0 < a < 1. On taking σCR into consideration, Eq. 7 becomes:

It has been reported that the fatigue life is proportional to the surface hardness and the reciprocal of the surface roughness.36 Therefore, the following equation can be used to describe the relationship between each of the variables:

Here, b is constant with 0 < b < 1. In Fig. 7, the 5 data points plotted in Figs. 3 and 5 were used to obtain a and b by the method of least squares. Namely, a and b were obtained from the relationship between Nf330exp and Nf 330 est by the method of least squares. In the present calculation, Rz was used the value of λc = 2.5 mm, as the correlation coefficient was better than that of the others. The correlation coefficient for the 5 data points is 0.958, and the probability of non-correlation is less than 1.0%. Note that, when non-correlation is less than 1%, it can be concluded that the relationship is highly significant. Thus, it can be concluded that the relationship between Nf 330 exp and Nf 330 est is highly significant. That is, Nf 330 is closely related to Rz′ with λc = 2.5 mm, the surface hardness HR15T′ and the compressive residual stress σCR, each of which were used for the estimation. Note that the values of a and b obtained were 0.081 and 0.660, respectively. The results suggest that the contribution of the compressive residual stress to the improvement made in the fatigue life is about 8% of the total contribution, and that the effects of Rz and HR15T are larger than that due to σCR at the present condition.

Conclusion

In order to improve the fatigue properties of titanium alloy Ti6Al4V manufactured by EBPB, we have developed a novel method using an abrasive cavitating jet and peening process that both smooths and introduces compressive residual stress into the surface. The injection pressure of the abrasive cavitating jet was set to 62 MPa, and the nozzle throat diameter was 0.64 mm. The distance between the nozzle and the specimen was set such that the conditions were optimized for cavitation peening. The fatigue properties were evaluated using a plane-bending fatigue test. The results obtained can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

The abrasive cavitating jet and peening process improved both the fatigue life and strength. There was an optimum processing time for the proposed treatment, at which the fatigue strength of the treated specimen was improved by 66%. The improvements in the fatigue properties were obtained as a result of the smoothing of the roughness, work-hardening and the introduction of surface/sub-surface compressive residual stress. Under the conditions used here, the effects of smoothing and work-hardening were greater than the effect of introducing compressive residual stress.

- (2)

The abrasive cavitating jet and peening process smoothed the inherent surface roughness of the Ti6Al4V. There was an optimum processing time for this. At the optimum processing time, the surface roughness was reduced by factors of approximately 8 with λc = 0.25 mm, 4 with λc = 0.8 mm and 2.5 with λc = 2.5 mm, where λc is the cutoff length of the stylus in the profilometer.

- (3)

The abrasive cavitating jet introduced compressive residual stress of 220 MPa into the surface of the metal specimens. Under the conditions used here, the contribution of the compressive residual stress to the improvement made in the fatigue life is about 8% of the total contribution.

- (4)

The surfaces of the Ti6Al4V specimens were work hardened by the abrasive cavitating jet.

References

P. Edwards, A. O’Conner, and M. Ramulu, J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. Trans. ASME 135, 1 (2013).

M. Seifi, A. Salem, J. Beuth, O. Harrysson, and J.J. Lewandowski, JOM 68, 747 (2016).

J. Gunther, S. Leuders, P. Koppa, T. Troster, S. Henkel, H. Biermann, and T. Niendorf, Mater. Des. 143, 1 (2018).

K.S. Chan, M. Koike, R.L. Mason, and T. Okabe, Metall. Mater. Trans. A 44A, 1010 (2013).

H.K. Rafi, N.V. Karthik, H.J. Gong, T.L. Starr, and B.E. Stucker, J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 22, 3872 (2013).

H.J. Gong, K. Rafi, H.F. Gu, G.D.J. Ram, T. Starr, and B. Stucker, Mater. Des. 86, 545 (2015).

M. Seifi, M. Gorelik, J. Waller, N. Hrabe, N. Shamsaei, S. Daniewicz, and J.J. Lewandowski, JOM 69, 439 (2017).

M. Fousova, D. Vojtech, K. Doubrava, M. Daniel, and C.F. Lin, Materials 11, 18 (2018).

P. Edwards and M. Ramulu, Mater. Sci. Eng., A 598, 327 (2014).

D. Greitemeier, C.D. Donne, F. Syassen, J. Eufinger, and T. Melz, Mater. Sci. Technol. 32, 629 (2016).

S. Bagehorn, J. Wehr, and H.J. Maier, Int. J. Fatigue 102, 135 (2017).

V. Chastand, P. Quaegebeur, W. Maia, and E. Charkaluk, Mater. Charact. 143, 76 (2018).

G. Nicoletto, R. Konecna, M. Frkan, and E. Riva, Int. J. Fatigue 116, 140 (2018).

J. Pegues, M. Roach, R.S. Williamson, and N. Shamsaei, Int. J. Fatigue 116, 543 (2018).

M.P. Sealy, G. Madireddy, R.E. Williams, P. Rao, and M. Toursangsaraki, J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. Trans. ASME 140, 13 (2018).

M. Sato, O. Takakuwa, M. Nakai, M. Niinomi, F. Takeo, and H. Soyama, Mater. Sci. Appl. 7, 181 (2016).

A. Dolimont, E. Riviere-Lorphevre, F. Ducobu, and S. Backaert, in Proceedings of the 21st international esaform conference on material forming, 140007–1, (2018).

B. Rosa, P. Mognol, and J.Y. Hascoet, J. Laser Appl. 27, 7 (2015).

D. Bhaduri, P. Penchev, A. Batal, S. Dimov, S.L. Soo, S. Sten, U. Harrysson, Z.X. Zhang, and H.S. Dong, Appl. Surf. Sci. 405, 29 (2017).

V. Schulze, F. Bleicher, P. Groche, Y.B. Guo, and Y.S. Pyune, CIRP Ann. Manuf. Technol. 65, 809 (2016).

P. Peyre, R. Fabbro, P. Merrien, and H.P. Lieurade, Mater. Sci. Eng., A 210, 102 (1996).

Y. Sano, M. Obata, T. Kubo, N. Mukai, M. Yoda, K. Masaki, and Y. Ochi, Mater. Sci. Eng., A 417, 334 (2006).

H. Soyama, K. Saito, and M. Saka, J. Eng. Mater. Technol. Trans. ASME 124, 135 (2002).

H. Soyama, Int. J. Peen Sci. Technol. 1, 3 (2017).

W. Guo, R.J. Sun, B.W. Song, Y. Zhu, F. Li, Z.G. Che, B. Li, C. Guo, L. Liu, and P. Peng, Surf. Coat. Technol. 349, 503 (2018).

H. Soyama and Y. Okura, AIMS Mater. Sci. 5, 1000 (2018).

H. Soyama, M. Shimizu, Y. Hattori, and Y. Nagasawa, J. Mater. Sci. 43, 5028 (2008).

H. Soyama, Mater. Sci. Appl. 5, 430 (2014).

L.C. Zhang, Y.J. Liu, S.J. Li, and Y.L. Hao, Adv. Eng. Mater. 20, 16 (2018).

H. Soyama, J. Fluids Eng. Trans. ASME 133, 101301 (2011).

B.B. He, Two-Dimensional X-ray Diffraction (Wiley, Hoboken, 2009), p. 249

O. Takakuwa and H. Soyama, Adv. Mater. Phys. Chem. 3, 8 (2013).

H. Soyama, R. Oba, and H. Kato, in Proceedings of the institute of mechanical engineering, 3rd international conference of the cavitation, vol. 103 (1992).

R.E. Little, ASTM STP 511, 29 (1972).

National Research Institute for Metals, Japan, Fatigue Data Sheet, No. 85, 1 (2000).

T. Kokubun and H. Soyama, Trans. JSME 83, 1 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 17H03138. The abrasive cavitating jet apparatus was financially supported by Boeing Research and Technology (BR&T).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Soyama, H., Sanders, D. Use of an Abrasive Water Cavitating Jet and Peening Process to Improve the Fatigue Strength of Titanium Alloy 6Al-4V Manufactured by the Electron Beam Powder Bed Melting (EBPB) Additive Manufacturing Method. JOM 71, 4311–4318 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11837-019-03673-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11837-019-03673-8