Abstract

Background

Obesity affects 1.5 billion people worldwide, yet few are treated effectively and considerable variability exists in its management. In 2020, a joint International Federation of Surgery for Obesity and Metabolic Diseases (IFSO) and World Gastroenterology Organization (WGO) advisory committee initiated the drafting of consensus guidelines on obesity management, to be based on detailed literature reviews and the results of an extensive multi-disciplinary survey of intercontinental experts. This paper reports on the latter. The objective of this study is to identify areas of consensus and non-consensus among intercontinental, inter-disciplinary experts in obesity management.

Methods

Guided by an international consensus-survey expert, a three-round online Delphi survey was conducted in the summer of 2021 of international obesity-management experts spanning the fields of medicine, bariatric endoscopy and surgery, psychology, and nutrition. Issues like epidemiology and risk factors, patient selection for metabolic and bariatric surgery (ASMBS-Clinical-Issues-Committee, Surg Obes Relat Dis : Off J Am Soc Bariatric Surg. 8:e27-32, 1), psychological issues, patient preparation for MBS, bariatric endoscopy, and outcomes and follow-up were addressed.

Results

Ninety-four experts from six continents voted on 180 statements, with consensus reached on 158, including consensus agreement with 96 and disagreement with 24 statements (38 had other response options besides agree/disagree). Among unanimous opinions were the need for all medical societies to work together to address obesity, for regular regional and national obesity surveillance, for multi-disciplinary management, to recognize the increasing impact of childhood and adolescent obesity, to accept some weight regain as normal after MBS, and for life-long follow-up of MBS patients.

Conclusions

Obesity is a major health issue that requires aggressive surveillance and thoughtful multidisciplinary management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Approximately 1.5 billion people worldwide currently live with obesity [1], and this number is rising [2,3,4], even among children and adolescents [5]. Beyond its own implications for health and fitness, obesity increases the risk of numerous other potentially life-threatening complications, like type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [6], cardiovascular disease [7], and at least 13 distinct types of cancer [8, 9]. Excess weight has also been linked to significantly decreased quality of life (QoL) [2], significantly increased risk of early mortality, decreased life expectancy [10], and increased cancer-related mortality [11]. These risks even extend to childhood obesity [12].

Managing obesity is difficult, with “eating less and exercising more” rarely attaining long-term success. Consequently, and because of the numerous obesity-associated comorbidities, obesity has been termed “a chronic relapsing progressive disease” [13]. While dietary changes, other lifestyle changes like exercise, and counselling remain the first line of treatment, relatively recent advances in obesity management have included pharmacological, endoscopic, and surgical interventions. Metabolic and bariatric surgery (MBS) remains significantly more effective than dietary and lifestyle changes alone at inducing weight loss, reducing comorbidities, and improving QoL [14,15,16,17].

Several operative interventions currently exist and which procedure is chosen and when to offer surgery varies between practices and regions [18]. Bariatric procedures also carry their own risks, including a low, but non-negligible (0.15–0.35%) risk of peri-operative mortality [19, 20]. Additional complications of MBS include potentially fatal nutritional deficiencies [21,22,23,24]; post-operative bleeding, intestinal obstructions, severe gastroesophageal reflux, and various gastrointestinal syndromes [19]. Patients undergoing MBS may also be prone to developing new post-operative addictive behaviours like substance abuse [25]. Consequently, MBS should not be used to replace, but to supplement other, non-operative approaches to obesity management, including dietary and lifestyle changes. It is also important to identify and treat psychopathology, utilizing psychosocial counselling and pharmacotherapy [25]. However, like choosing operative procedures, variability exists in how and to what extent such services are co-administered [26]. Variability also exists in which patients are considered eligible and safe for endoscopic and bariatric procedures [27]; how to define treatment success and failure [16, 28]; how much weight regain should be considered acceptable [29]; and which metric to utilize for measuring weight regain (e.g., as a percentage of excess vs. total weight) [30].

It was such variability and uncertainty that led the World Gastroenterology Organization (WGO) and International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO) to join forces in 2020 to take steps towards drafting international guidelines on the management and long-term monitoring of obesity. This included undertaking a survey of 94 international, interdisciplinary experts in obesity management to identify areas of consensus and non-consensus spanning a range of topics. This paper reports those results.

Methods

An online modified Delphi survey was conducted following published guidelines [31]. The Delphi approach was adopted because of its exponentiallyincreasing utilization in health science and other fields and its unanimous voting, thereby reducing the risk of conformity/acquiescence bias typically ascribed to in-person consensus meetings [31].

Survey development with each steering committee member generating a list of issues/questions of major interest within their own discipline. To be considered for survey inclusion, the issue could not already be considered a firmly established, universal standard of care based upon published empirical evidence, but had to be considered of appreciable importance to obesity management. Issues of interest ranged from epidemiology and public perceptions to treatment and follow-up.

All submitted statements were sent to the steering committee for statement selection; then to the Delphi expert for editing, consolidation into a single survey, and reformatting to ensure comprehensibility and consistency. Several steps were undertaken to reduce any risk of bias potentially induced by the survey itself, including primarily using non-judgmental statements (e.g., neither favouring nor opposing a particular concept/belief/approach); balancing the remaining favourable and unfavorable statements; and altering the order of response options to minimize order bias (e.g., favorable options listed anywhere from first to last). The survey’s first full draft was sent to all steering-committee members for feedback and potential modification, after which a pilot survey of 10 experts was conducted to identify all language, factual, or conceptual issues.

The final Round 1 survey had 157 statements subdivided into six modules: Module 1: Epidemiology and risk factors (20 statements); Module 2: Patient selection for MBS (29 statements); Module 3: Psychological issues (14 statements); Module 4: Patient preparation for MBS (23 statements); Module 5: Bariatric endoscopy (39 statements, only voted on by surgeons and endoscopists); and Module 6: Outcomes and follow-up (32 statements). Statements failing to achieve ≥ 70% consensus were included in a second-round survey. Each expert was asked at both the start and end of each module how comfortable they felt voting on that module’s focus, rated from very uncomfortable to very comfortable so votes from uncomfortable voters could be excluded during data analysis. At least 80% participation of eligible voters on any statement was required for that statement’s vote tally to be considered valid.

In June 2021, an email was sent to 100 experts who had previously agreed to participate in the survey, including a link to the above-mentioned, committee-approved Round 1 survey on the online platform Survey Monkey. Practice characteristics of the 94 who ultimately participated, and of the n = 37 bariatric surgeons and n = 55 with experience in bariatric endoscopy are summarized in Table 1.

Results

Among the five modules open to all experts, voter numbers ranged from 80 to 94 (85–100%) out of 94; for Module 5, restricted to 58 bariatric surgeons and/or endoscopists, voter numbers ranged from 54 to 58 (94.7–100%). Hence, a valid vote was achieved for every statement.

After Round 1 results were analyzed, 23 statements on the “relative importance of pre-operative patient factors” were added to the Round 2 survey. Final analysis was, therefore, of 180 (157 + 23) statements.

Among the 180 statements included in final analysis, only 17 (9.4%) were deemed by the advisory panel as favorable to a particular concept/belief/approach, 19 unfavorable (10.6%), and 144 (80.0%) non-judgmental (Table 2). An abbreviated third round of voting was conducted for the eight of 23 statements added to Round 2 for which no consensus was achieved in that round, thereby permitting two rounds of voting on all statements requiring a second vote.

At least 70% consensus was achieved on 158 statements (87.8%)—114 first round, 44 s round. However, 100% consensus was only achieved for 12 statements. Table 2 provides further general results.

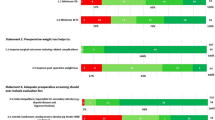

The results for each of the six modules are summarized individually in Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9, with Module 2 subdivided into part A (Table 4) and part B (Table 5).

On epidemiology and risk factors, unanimous consensus was reached that all medical societies must address obesity systematically and that regular longitudinal national and regional surveillance is necessary. Strong consensus was achieved defining obesity as a chronic disease that increases both morbidity and mortality risks; that emotional eating is a common feature but also that eating binges not universal among those with obesity; and that ethnicity and geographical factors are important, both pathophysiologically and when considering interventions. Experts agreed that food addiction is a valid clinical entity, and common among patients undergoing MBS, especially those with problematic alcohol and/or drug use; but were split on whether food addiction affects a great majority of patients considering MBS. They also agreed that binge eating is a risk factor for weight regain after MBS, but disagreed it is a risk factor for suicidal ideations/attempts. All Module 1 results are summarized in Table 3.

On patient selection (Table 4), there was 100% consensus that global rates of obesity are increasing in children and adolescents; that obesity during childhood or adolescence portends obesity in adulthood; that severe obesity in the young portends significant obesity-related co-morbidity, like diabetes and hypertension; that MBS in youths requires a multi-disciplinary team with experience dealing with youths and their families; and that inadequate public and physician knowledge and scarce long-term results of MBS in youths are barriers to MBS use in youths. There also was near-unanimous agreement that life-long monitoring is necessary for youths who undergo MBS and that MBS in youths should be performed by experienced bariatric surgeons with a proven track record of success in adults. Experts agreed that enough empirical evidence has been published supporting MBS as the most effective therapy for severe obesity in youths and that MBS outcomes in youths are similar to those achieved in adults. However, certain MBS procedures, like biliopancreatic diversion (BD) and one-anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB), were not recommended for youths.

Considering seniors, there again was consensus that MBS is generally effective and safe and increases QoL and that age should not be the only consideration when deciding on surgery. Conversely, there was consensus that operating time is directly predictive of negative outcomes in seniors, and that seniors’ risks from MBS are greater than adolescents. No consensus was reached concerning on the age when operative candidates should be considered elderly, on outcomes post-Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) relative to outcomes in adolescents, or on the gold standard MBS procedure for seniors. Table 5 ranks 23 pre-operative factors by their relative level of importance, with all but financial means and thyroid disease considered very important by ≥ 70% of our experts.

Among psychological issues, there was consensus disagreement that patients undergoing MBS always develop problematic alcohol use or mostly experience worsened depression post-operatively. Experts also disagreed that those patients with pre-MBS cognitive depressive symptoms usually do not improve post-operatively, as opposed to those who have meaningful post-operative weight loss and usually experience improvement in their depression post MBS. However, there also was consensus agreement that suicide is more common in patients who have undergone MBS. Strong consensus was reached that a comprehensive psychological evaluation is necessary pre-operatively, and that even patients with severe psychiatric illness can undergo MBS if it is well controlled. Experts also agreed that patients with food addiction are more likely to have other psychiatric conditions—like depression and anxiety—than those without, and that cognitive behavioral therapy is the best therapeutic strategy for patients at high risk of binge eating. Further results on psychological issues are summarized in Table 6.

For preparatory steps prior to MBS, consensus was reached on the need for comprehensive medical and nutritional evaluations, identifying and correcting all nutritional deficiencies, smoking cessation, and pre-operative endoscopy, with sleep apnea screening only necessary in those considered at high risk. Experts disagreed that routine CT or MRI is required to screen for hepatocellular carcinoma prior to MBS and that all anti-diabetic drugs reduce the risk of this cancer in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Table 7 summarizes further results, including anti-COVID 19 steps to take prior to MBS.

Among the 58 experts who performed endoscopic metabolic and bariatric therapy (EMBT), almost unanimous consensus was reached on the unique and important roles these procedures have managing obesity; that adequate endoscopic bariatric training is required for practitioners; and that MBS centers should communicate a comprehensive care plan to patients and their primary care providers, including testing, supplements, and when to be referred back for re-evaluation. Table 8 also specifically summarizes consensus opinions on aspiration therapy, duodenal procedures, endoscopic gastric bypass, gastric plication and suturing procedures, and intragastric balloons (IGBs). Among these, the greatest support was expressed for IGB and least for aspiration therapy and duodenal bypass, with intermediate support expressed for gastric procedures involving bypass, plication, or suturing, depending on the situation. The only procedures for which currently published empirical evidence was considered adequately supportive for them to no longer be considered of uncertain efficacy were those involving balloons. Intragastric balloons also were the only procedures considered acceptable for the sole purpose of helping patients “look better” and were voted acceptable “bridge therapy” for patients scheduled for later MBS.

Regarding post-procedural follow-up and outcomes, unanimous consensus was expressed that some degree of weight regain is normal 2–10 years after MBS, but also that appreciable weight regain may require further medical, endoscopic, or surgical treatment. Experts also unanimously agreed that post-MBS follow-up should be lifelong and that MBS centers should work jointly with patients' primary care providers to provide follow-up and access to appropriate healthcare professionals, as indicated. Near-unanimous agreement was expressed on the potential need for further treatment in patients with continued severe obesity and obesity-related problems two years after MBS, and on the need for comprehensive multi-disciplinary assessments in patients experiencing appreciable post-operative weight regain. Unsatisfactory post-operative weight loss was also considered an indication for supplementary anti-obesity medication (AOM). However, 93.3% and 80.9% agreed, respectively, that no uniformly-recognized definitions exist for either “significant weight regain” or “surgical success.”

For follow-up, nutrition counselling was considered an essential component of post endoscopic treatment by 98.9%, while assessing bone health and ruling out gastroesophageal dysfunction were considered important in patients deemed at high risk for osteoporosis and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), respectively. Consensus agreement also was achieved on several statements pertaining to the benefits of MBS at a societal level. Further results are summarized in Table 9.

Discussion

Clinical management of people with obesity has evolved tremendously over the past decade as understanding of this chronic disease has improved. Such advances include more universal acceptance of obesity as a disease. Despite this, its prevalence continues to rise worldwide in all age groups [2,3,4] as is its economic burden on healthcare systems [32]. In addition, the percentage of patients seeking any form of effective therapy for their obesity remains very low. There is widespread agreement, even beyond the current panel of experts, that a dire need exists to alter obesity’s current world trajectory and find ways to both prevent and treat it in more individuals. Two options that achieved unanimous consensus in our expert panel might achieve both goals: first, for all medical societies to cooperate to address the problem systematically; and second, for longitudinal surveillance to be conducted routinely at both regional and national levels. Two examples of multinational obesity surveillance programs that have generated useful data are the Scandinavian Obesity Registry (SOReg) [33] and German Bariatric Surgery Registry [34], the latter having existed for > 60 years. Such data have generated publications on crucial issues like short-term and long-term outcomes after MBS and a 10-year post-operative mortality rate of just 0.06% over the first 90 post-operative days, as well as data on immediate and longer-term post-operative complications, weight loss, comorbidity management, impact of patient age on outcomes, and comparing different MBS procedures [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. Though such data are tremendously valuable, only a very small percentage of individuals with obesity ever undergo MBS, and it is the remaining huge majority for which closer surveillance remains necessary. More realistic, perhaps, are physician and public obesity education campaigns to increase awareness both about the health hazards associated with obesity (e.g., increased risk of cancer), and the need for comprehensive, multidisciplinary treatment, especially for those whose obesity has become severe and/or having obesity-associated comorbidities.

Another issue on which unanimous consensus was repeatedly reached was obesity in children and adolescents, all our experts agreeing that global rates of obesity are currently increasing in youths and that most youths with obesity continue to have obesity in adulthood. Additionally, youths with severe obesity are at risk of significant obesity-related comorbidities like diabetes. Unanimity also was expressed that MBS in adolescents requires an experienced, multi-disciplinary team with experience dealing with youths and their families, and that inadequate physician and public awareness and insufficient long-term outcome data are barriers against the referral of adolescents who might benefit from MBS. Pertaining to insufficient data, five meta-analyses documenting the beneficial effects of MBS in adolescents (including sustained weight reduction, improvements in some obesity-related comorbidities, and improved QoL) have been published [42,43,44,45,46]. However, few studies have had follow-up beyond five years and virtually none followed youths into adulthood. Data also are scant on potential nutritional and developmental difficulties [46].

In our survey, unanimous consensus was reached on five additional statements, all pertaining to surgical treatment or post-surgical follow-up. Unanimously expressed opinions were that multidisciplinary assessment is necessary prior to MBS; that some degree of weight regain is normal from 2 to 10 years after MBS; that significant weight regain, or the presence/persistence of obesity-related medical problems may require further medical, endoscopic, or surgical treatment; that follow-up after MBS should be lifelong; and that MBS centers should work jointly with their patients’ primary healthcare providers to ensure adequate follow-up and access to other healthcare professionals. Regarding MBS patient selection, the pre-operative factors rated very important by almost all experts were the patient’s overall level of health and fitness, presence and/or nature of comorbid illness, cognitive ability to understand the procedure and instructions, and presence of either alcohol or another substance abuse.

Repeatedly expressed was the need for multiple healthcare practitioners spanning different disciplines, especially for patients considering MBS. This should begin with a multi-disciplinary pre-operative assessment to determine each patient’s eligibility. Such assessments also are necessary to identify co-morbid medical, nutritional, and psychological disorders and barriers to treatment success and attempt to address as many of these barriers pre-operatively as possible. Also necessary is to otherwise prepare patients for surgery, including educating them concerning realistic goals, potential post-operative symptoms, high likelihood of some weight regain or other set-backs, and vital importance of continued, life-long follow-up. This multimodal management requires collaboration from members of a multidisciplinary team that includes dieticians/nutritionists, behavioral therapists, physicians, endocrinologists, endoscopists, and surgeons.

Post-operatively, patients continue to require ongoing, multi-disciplinary care to manage their weight loss program and obesity-associated comorbidities. They also require monitoring for the life-altering effects of surgery, like the risk of potentially catastrophic nutritional deficiencies that may vary depending on the specific MBS performed [22, 47]. Each patient’s psychological state must also be followed, given recent data suggesting a slightly elevated risk of suicide in both adolescents and adults who undergo MBS [48, 49]. Potential contributory factors include forced alterations in foods they can and cannot eat, gastrointestinal symptoms secondary to food intolerance, and unrealized, unrealistic expectations about the extent of weight loss they may experience post-operatively, leading to depression, anxiety, reduced sense of self-worth, and other forms of psychological distress. Monitoring also is essential to detect the re-emergence of detrimental eating patterns, like binge eating, as such factors may predict poorer post-operative weight management [50].

Every expert consensus survey has the potential for bias, given that participants may already have a predilection to utilize a particular practice to have become experts in its use. In addition to adopting the Delphi approach (characterized by voter anonymity, largely eliminating acquiescence bias), our survey was unique in that we sought the opinions of a uniquely-broad array of healthcare practitioners that included surgeons, non-surgical physicians, and non-physician experts in nutrition and psychological counselling. All participants were invited to vote on any statement with which they felt comfortable, except for one module on endoscopic therapy restricted to surgeons and endoscopists. Recognizing worldwide differences in obesity management, we also included experts from every permanently inhabited continent. In this manner, we attempted to minimize the widely held criticisms of consensus-survey critics of “like-minded individuals voting together.” We further worded survey statements so a sizeable majority neither favored nor opposed the concept/belief/approach presented, with the remaining statements evenly balanced between favorable and unfavorable. The order of response options also was altered so the most favorable option was listed anywhere from first to last.

We nonetheless acknowledge that consensus surveys are level V evidence, and based upon opinions, rather than experimentally-generated data. That said, all our voters were widely renowned experts in obesity management and, thus, both familiar with such research and particularly qualified to interpret it. In other words, their opinions were based not just upon their extensive experience, but on their expansive knowledge of relevant research. Moreover, as stated initially, this consensus survey was conducted to aid in generating joint IFSO-WGO guidelines, for which over 1000 scientific references have also been utilized to frame the discussion. The consensus opinions we sought to aid in drafting those guidelines were for issues for which existing literature is either non-definitive—requiring appreciable interpretation—or largely lacking, especially on issues that might be particularly difficult to study empirically, like whether EMBT can be justified for aesthetic purposes only.

Since the conclusion of this joint IFSO-WGO Delphi Survey, 2022 ASMBS/IFSO Guidelines on Indications for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery have been published, and many of those guidelines support our survey results [51].

References

ASMBS-Clinical-Issues-Committee. Peri-operative management of obstructive sleep apnea. Surg Obes Relat Dis : Off J Am Soc Bariatric Surg. 2012;8:e27-32.

Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB, et al. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:13–27.

NCD-Risk-Factor-Collaboration. Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19·2 million participants. Lancet (London, England). 2016;387:1377–96.

NCD-Risk-Factor-Collaboration. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet (London, England). 2017;390:2627–42.

NCD-Risk-Factor-Collaboration. Height and body-mass index trajectories of school-aged children and adolescents from 1985 to 2019 in 200 countries and territories: a pooled analysis of 2181 population-based studies with 65 million participants. Lancet (London, England). 2020;396:1511–24.

Abdullah A, Peeters A, de Courten M, et al. The magnitude of association between overweight and obesity and the risk of diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;89:309–19.

Powell-Wiley TM, Poirier P, Burke LE, et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143:e984–1010.

Avgerinos KI, Spyrou N, Mantzoros CS, et al. Obesity and cancer risk: Emerging biological mechanisms and perspectives. Metabolism. 2019;92:121–35.

Colditz GA, Peterson LL. Obesity and cancer: evidence, impact, and future directions. Clin Chem. 2018;64:154–62.

Peeters A, Barendregt JJ, Willekens F, et al. Obesity in adulthood and its consequences for life expectancy: a life-table analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:24–32.

Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, et al. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625–38.

Llewellyn A, Simmonds M, Owen CG, et al. Childhood obesity as a predictor of morbidity in adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2016;17:56–67.

Bray GA, Kim KK, Wilding JPH. Obesity: a chronic relapsing progressive disease process. A position statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obes Rev. 2017;18:715–23.

Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, et al. Bariatric Surgery and Endoluminal Procedures: IFSO Worldwide Survey 2014. Obes Surg. 2017;27:2279–89.

Malik VS, Willett WC, Hu FB. Global obesity: trends, risk factors and policy implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9:13–27.

Reynolds CL, Byrne SM, Hamdorf JM. Treatment success: investigating clinically significant change in quality of life following bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2017;27:1842–8.

Seidell JC, Halberstadt J. The global burden of obesity and the challenges of prevention. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66(Suppl 2):7–12.

Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, et al. bariatric surgery survey 2018: similarities and disparities among the 5 IFSO chapters. Obes Surg. 2021;31:1937–48.

Goel R, Nasta AM, Goel M, et al. Complications after bariatric surgery: A multicentric study of 11,568 patients from Indian bariatric surgery outcomes reporting group. J Minim Access Surg. 2021;17:213–20.

Pories WJ. Bariatric surgery: risks and rewards. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:S89-96.

Lupoli R, Lembo E, Saldalamacchia G, et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term nutritional issues. World J Diabetes. 2017;8:464–74.

Parrott J, Frank L, Rabena R, et al. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Integrated Health Nutritional Guidelines for the Surgical Weight Loss Patient 2016 Update: Micronutrients. Surg Obes Relat Dis : Off J Am Soc Bariatric Surg. 2017;13:727–41.

Shoar S, Poliakin L, Rubenstein R, et al. Single Anastomosis Duodeno-Ileal Switch (SADIS): A Systematic Review of Efficacy and Safety. Obes Surg. 2018;28:104–13.

Stroh C, Manger T, Benedix F. Metabolic surgery and nutritional deficiencies. Minerva Chir. 2017;72:432–41.

Koball AM, Ames G, Goetze RE. Addiction transfer and other behavioral changes following bariatric surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2021;101:323–33.

Bauchowitz AU, Gonder-Frederick LA, Olbrisch ME, et al. Psychosocial evaluation of bariatric surgery candidates: a survey of present practices. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:825–32.

Choban PS, Jackson B, Poplawski S, et al. Bariatric surgery for morbid obesity: why, who, when, how, where, and then what? Cleve Clin J Med. 2002;69:897–903.

Madura JA 2nd, Dibaise JK. Quick fix or long-term cure? Pros and cons of bariatric surgery. F1000 Med Rep. 2012;4:19.

King WC, Hinerman AS, Courcoulas AP. Weight regain after bariatric surgery: a systematic literature review and comparison across studies using a large reference sample. Surg Obes Relat Dis : Off J Am Soc Bariatric Surg. 2020;16:1133–44.

King WC, Hinerman AS, Belle SH, et al. Comparison of the performance of common measures of weight regain after bariatric surgery for association with clinical outcomes. JAMA. 2018;320:1560–9.

Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna H. The Delphi technique in nursing and health research. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

Tremmel M, Gerdtham UG, Nilsson PM, et al. Economic burden of obesity: a systematic literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(4):435.

Anderin C, Gustafsson UO, Heijbel N, et al. Weight loss before bariatric surgery and postoperative complications: data from the Scandinavian Obesity Registry (SOReg). Ann Surg. 2015;261:909–13.

Hajer AA, Wolff S, Benedix F, et al. Trends in early morbidity and mortality after sleeve gastrectomy in patients over 60 years: retrospective review and data analysis of the German Bariatric Surgery Registry. Obes Surg. 2018;28:1831–7.

Edholm D, Axer S, Hedberg J, et al. Laparoscopy in Duodenal Switch: safe and Halves Length of Stay in a Nationwide Cohort from the Scandinavian Obesity Registry. Scand J Surg : SJS : Off Organ Finn Surg Soc Scand Surg Soc. 2017;106:230–4.

Edholm D, Sundbom M. Comparison between circular- and linear-stapled gastrojejunostomy in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass–a cohort from the Scandinavian Obesity Registry. Surg Obes Relat Dis : Off J Am Soc Bariatric Surg. 2015;11:1233–6.

Gerber P, Anderin C, Gustafsson UO, et al. Weight loss before gastric bypass and postoperative weight change: data from the Scandinavian Obesity Registry (SOReg). Surg Obes Relat Dis : Off J Am Soc Bariatric Surg. 2016;12:556–62.

Gerber P, Gustafsson UO, Anderin C, et al. Effect of age on quality of life after gastric bypass: data from the Scandinavian Obesity Surgery Registry. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2022;18:1313–22.

Pop B, Fetica B, Blaga ML, et al. The role of medical registries, potential applications and limitations. Med Pharm Rep. 2019;92:7–14.

Sundbom M, Näslund E, Vidarsson B, et al. Low overall mortality during 10 years of bariatric surgery: nationwide study on 63,469 procedures from the Scandinavian Obesity Registry. Surg Obes Relat Dis : Off J Am Soc Bariatric Surg. 2020;16:65–70.

Tao W, Holmberg D, Näslund E, et al. Validation of obesity surgery data in the Swedish National Patient Registry and Scandinavian Obesity Registry (SOReg). Obes Surg. 2016;26:1750–6.

Black JA, White B, Viner RM, et al. Bariatric surgery for obese children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2013;14:634–44.

Paulus GF, de Vaan LE, Verdam FJ, et al. Bariatric surgery in morbidly obese adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2015;25:860–78.

Pedroso FE, Angriman F, Endo A, et al. Weight loss after bariatric surgery in obese adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis : Off J Am Soc Bariatric Surg. 2018;14:413–22.

Qi L, Guo Y, Liu CQ, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on glycemic and lipid metabolism, surgical complication and quality of life in adolescents with obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis : Off J Am Soc Bariatric Surg. 2017;13:2037–55.

Shoar S, Mahmoudzadeh H, Naderan M, et al. Long-term outcome of bariatric surgery in morbidly obese adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 950 patients with a minimum of 3 years follow-up. Obes Surg. 2017;27:3110–7.

O’Kane M. Nutritional consequences of bariatric surgery - prevention, detection and management. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2021;37:135–44.

Järvholm K, Olbers T, Peltonen M, et al. Depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation in young adults 5 years after undergoing bariatric surgery as adolescents. Eat Weight Disord. 2021;26:1211–21.

Kauppila JH, Santoni G, Tao W, et al. Risk factors for suicide after bariatric surgery in a population-based nationwide study in five Nordic countries. Ann Surg. 2022;275:e410–4.

Livhits M, Mercado C, Yermilov I, et al. Preoperative predictors of weight loss following bariatric surgery: systematic review. Obes Surg. 2012;22:70–89.

Eisenberg D, Shikora SA, Aarts E, et al. 2022 American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO) indications for metabolic and bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2023;33:3–14.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the collaborations from both IFSO and WGO members for their participation in this Delphi study. For IFSO, we would like to thank Manuela Mazzarella, Chief Operating Officer, and for WGO Marissa Lopez, Executive Director.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Key Points

• International consensus survey on obesity.

• Delphi survey on bariatric surgery, bariatric endoscopy, nutrition, psychology.

• Multidisciplinary management of obesity.

These guidelines are being co-published by Springer Nature (Obesity Surgery, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-023-06757-2) and Wolters Kluwer (Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0000000000001916).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kow, L., Sharaiha, R.Z., O’Kane, M. et al. Methodology and Results of a Joint IFSO-WGO Delphi Survey of 94 Intercontinental, Interdisciplinary Experts in Obesity Management. OBES SURG 33, 3337–3352 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-023-06757-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-023-06757-2