Abstract

Introduction

This survey of international experts in obesity management was conducted to achieve consensus on standardized definitions and to identify areas of consensus and non-consensus in metabolic bariatric surgery (MBS) to assist in an algorithm of clinical practice guidelines for the management of obesity.

Methods

A three-round Delphi survey with 136 statements was conducted by 43 experts in obesity management comprising 26 bariatric surgeons, 4 endoscopists, 8 endocrinologists, 2 nutritionists, 2 counsellors, an internist, and a pediatrician spanning six continents over a 2-day meeting in Hamburg, Germany. To reduce bias, voting was unanimous, and the statements were neither favorable nor unfavorable to the issue voted or evenly balanced between favorable and unfavorable. Consensus was defined as ≥ 70% inter-voter agreement.

Results

Consensus was reached on all 15 essential definitional and reporting statements, including initial suboptimal clinical response, baseline weight, recurrent weight gain, conversion, and revision surgery. Consensus was reached on 95/121 statements on the type of surgical procedures favoring Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty. Moderate consensus was reached for sleeve gastrectomy single-anastomosis duodenoileostomy and none on the role of intra-gastric balloons. Consensus was reached for MBS in patients > 65 and < 18 years old, with a BMI > 50 kg/m2, and with various obesity-related complications such as type 2 diabetes, liver, and kidney disease.

Conclusions

In this survey of 43 multi-disciplinary experts, consensus was reached on standardized definitions and reporting standards applicable to the whole medical community. An algorithm for treating patients with obesity was explored utilizing a thoughtful multimodal approach.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The prevalence of obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) is anticipated to rise from 14% in 2020 to 24% over the next 15 years and hence predicted to affect nearly 2 billion adults, children, and adolescents by 2035 [1]. The rapid rise of obesity in children and adolescents is especially concerning, since obesity in adolescence typically persists into adulthood and predisposes individuals to numerous complications [2]. Most notable obesity-associated comorbidities and complications include type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [3], cardiovascular disease [4], obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) [5], increased risks of various cancers and mortality [6, 7], reduced quality of life (QOL) [8], and increased risk of death [9,10,11].

Obesity is a highly heterogeneous and progressive multifactorial disease [12]. Metabolic and bariatric surgery (MBS) is the most effective treatment for severe obesity, generating substantial, sustained weight reduction, along with improvements in comorbidities and quality of life, and increased life expectancy [10, 11]. Although MBS is the most effective anti-obesity intervention, there are large variations in treatment response after MBS [13, 14], mainly due to the heterogeneity of the disease. New anti-obesity medications (AOMs) and endoscopic bariatric procedures are extremely welcome additions to the treatment of obesity linked to promising weight loss and favorable associated metabolic changes, in selected patients [15]. With the increased availability of potent AOMs now and in the near future, the practice of combination therapy will grow as MBS and AOMs can work in synergy on the treatment of severe obesity and hopefully in enabling increased access to effective obesity treatments.

In addition to the two most common surgical procedures—sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB)—there are numerous other MBS procedures and considerable variation between practices and regions [16]. Variations in reported MBS outcomes (e.g., lack of uniform standardized reporting definitions) are evident in the MBS literature and markedly limit the comparability of different studies, creating a major hindrance to evidence-based clinical obesity treatment algorithms. In 2015, the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) published reporting standards in MBS aiming to enhance the quality and comparability of MBS results [17]. However, only four studies published from 2015 to 2020 have used the recommended ASMBS reporting standards, resulting in low compliance and implementation of such standards in clinical practice [18]. This highlights the importance of having valid, simple-to-use definitions for both clinical practice and research that are acceptable and applicable to the surgical and medical communities.

The aim of this consensus meeting and Delphi survey of international experts in obesity management was to achieve consensus on standardized uniform reporting definitions and standards for the whole medical community to assist in developing clinical practice guidelines for the management of severe obesity and particularly for MBS. Specific aims were to identify areas of expert consensus to assist with algorithm development, combined with a thorough review of published literature, and to identify areas of non-consensus to flag topics warranting further research.

Methods

A three-round Delphi survey of 43 intercontinental, interdisciplinary experts in obesity management was conducted, beginning with in-person voting over 2 days in Hamburg, Germany, from March 9 to 10, 2023, followed by discussion and two rounds of online voting. The invited expert panel included bariatric surgeons, pediatric bariatric surgeons, bariatric endoscopists, endocrinologists, pediatricians, dieticians, psychologists, and counsellors with obesity management expertise. To be considered for the expert panel, clinicians had to have obesity management as a major focus of their practice, be considered experts by IFSO, have ≥ 10 years’ experience managing patients with obesity, be fluent in both spoken and written English, and be willing to attend, preferably in person, a 2-day conference in Hamburg for expert lectures on published evidence-based literature with graded-level evidence, open discussion, and a Delphi survey.

Survey Development

In January 2023, each expert participant was asked to contribute 3–5 statements within their field for consideration by a core advisory group comprised of IFSO members and an MD-PhD level expert in Delphi surveys. This yielded > 300 submitted statements. Over six virtual meetings of the core advisory group, these were pared down to 136 statements subdivided into four Modules: 1, definitions (15 statements); 2, conservative and medical management (21 statements); 3, endoscopy (14 statements); and 4, metabolic bariatric surgery (86 statements). These 136 statements spanning Modules 1–4 then were balanced by the Delphi expert to minimize the risk that the survey instrument itself might induce bias by using response options other than agree/disagree, converting as many statements as possible into non-judgmental statements (neither favorable nor unfavorable to the concept presented), balancing all remaining statements to ensure roughly equal numbers of favorable and non-favorable statements, and adjusting the response options so favorable options were equally distributed in response order. The survey was then reviewed by all advisory group members for a pilot test and final editing. Consensus was defined as ≥ 70% inter-voter agreement, and a valid vote as voter participation ≥ 80%. Voting on statements specifically addressing the technical aspects of MBS was restricted to clinicians with sufficient expertise on the issue.

Given the critical importance of establishing consensus on definitions prior to progressing to statements on treatment specifics, the advisory panel dedicated Day #1 of the conference to Module 1, with open discussion prior to voting, and Day #2 to Modules 2–4, using published Delphi survey guidelines [19]. The current literature and level of evidence on all statements were presented by the specific experts to the whole consensus group prior to open discussion and voting. The 2-day conference in-person discussion and voting and online voting procedures are depicted in detail in both text and schematic form in online Supplement 1.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was completed between rounds to identify statements with 70% consensus reached or not reached, and whether adequate voter participation had been achieved. Statements not achieving either 70% consensus or 80% eligible voter participation were included in the next round of voting.

Results

The 43-member expert panel included 17 from Europe, 13 from North America, six from Latin America, 5 from the Middle East and Northern Africa, and 2 from Asia-Oceania. There were 26 bariatric surgeons including 2 pediatric bariatric surgeons, among whom 11 also performed endoscopic bariatric procedures. The remaining expert panel members were four endoscopists, eight endocrinologists, one internist, one pediatrician, two nutritionists, and two counsellors (psychology, exercise).

The final survey had 136 statements, with one deleted from Module 4 because it duplicated an earlier statement. Forty-seven statements underwent change after Round 1 to such a degree that the Round 1 results were considered invalid and considered new statements in Round 2A.

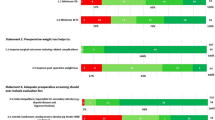

Since we considered it critical to achieve consensus on all the definition statements (Module 1), and considerable discussion occurred to achieve this, consensus was reached on all 15 at a mean level of 90.1% consensus. There was great variability over Modules 2–4 on both the percentage of statements on which consensus was reached (50.0–95.2%) and the overall mean level of consensus achieved (66.7–86.9%). Consensus was reached on 68/85 MBS statements with a mean level of consensus of 79.6% (Supplementary Table A). Among the 38 statements that required two rounds of voting, consensus only was reached on 13: both statements on definitions and 11 of the 28 MBS statements. All seven statements on endoscopy failing to achieve consensus in Round 1 also failed in Round 2 (Supplementary Table B).

Module 1—Definitions

Module 1 results for 15 definitions statements are listed in Table 1. A suboptimal initial response was unanimously defined as inadequate weight loss or an unusually modest improvement in a clinically significant obesity complication, and 39/40 experts agreed that the severity of a suboptimal response should guide treatment. Similar to suboptimal response, late postoperative deterioration was defined as recurrent weight gain or worsening of a significant obesity complication. Baseline weight in patients who undergo MBS was defined as that measured before starting preoperative weight reduction. With respect to the use of re-operative MBS to address either a suboptimal initial response, later clinical deterioration, or adverse events, experts agreed that surgical or endoscopic procedures to convert to a new type of MBS (conversion surgery) or to reestablish normal anatomy (reversal surgery) in major adverse events should be clearly distinguished and considered separately from procedures to modify or revise a previous operation (modification or revision surgery). Experts agreed that the presumed mechanism of action should not be used to describe MBS procedures, which instead should be labelled by the anatomical changes made. There was strong consensus on omitting demeaning terms like “super-obesity” to describe a BMI > 50 kg/m2 and on replacing such terms with a BMI-based classification system (e.g., class IV, BMI 50-60 kg/m2; class V, BMI > 60 kg/m2).

Modules 2–4

Results for Modules 2–4 are summarized in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, with all statements pertaining to conservative and medical management in Table 2; endoscopy, Table 3; specific MBS procedures, Table 4; special circumstances related to patient BMI and age (≤ 18, ≥ 65), Table 5; and obesity complications, Table 6.

Discussion

In this IFSO-sponsored expert consensus survey, we achieved unanimous consensus on all reporting definitions and reporting standards. This was accomplished by a multidisciplinary expert group, paving the way to implementing these definitions in clinical practice and research within both the surgical and medical communities. The other focus of this survey was to address MBS topics where long-term evidence-based data remain insufficient. It serves as a next step following the joint IFSO and World Gastroenterology Organization (WGO) Delphi survey conducted in the spring of 2022 examining all non-surgical approaches to obesity management, including patient assessment and preparation for MBS.

Our first major objective, which we considered vital to constructing any MBS guidelines, was to achieve consensus on essential definitions pertaining to surgical management of obesity—including definitions for weight loss attributable to MBS (versus concomitant therapies), baseline weight, suboptimal initial clinical response, recurrent weight gain, and distinguishing conversion from revision surgery. This we achieved, through considerable discussion and major modifications to original statements. As weight loss is the driving force behind positive outcomes after MBS, all statements on weight loss were written to standardize reporting, starting from baseline weight to nadir weight loss 2 years after surgery to recurrent weight gain. However, as the outcome of MBS is a composite endpoint, obesity comorbidities and complications are included in the definitions.

The uniform standardized use of these definitions paves the way to enhancing comparability of the reoperations and their indications within the field of obesity treatment and MBS. The current literature mixes revisional surgery and conversion surgery terms, not to mention the variability of indications for reoperation. The firm consensus of our experts was to clearly differentiate these terms as modification or revision procedures are typically designed to optimize the effectiveness of previous operations, while conversion procedures most commonly introduce additional mechanisms of therapeutic action. For the accurate categorization of different procedures, the consensus was reached that MBS procedures should be labelled by the anatomical changes made intraoperatively (e.g., gastric bypass), rather than by presumed mechanisms of action (e.g., restriction, malabsorption, or hypo-absorption). The rationale was that the mechanisms by which MBS procedures work are complex, frequently multi-faceted (e.g., involving other factors like hormonal and neuronal effects), and often incompletely understood.

The biological basis of obesity and the response to MBS underscore the importance of recognizing that a suboptimal clinical response rarely reflects either substandard surgical skill or technique. Similarly, it is rarely caused by noncompliance or other aberrant or inadequate behavior by the patient. Thus, the language we use to describe less robust clinical outcomes must avoid being judgemental, ascribing blame, or drawing unproven, causal inferences. Thus, by consensus, we recommend that less than ideal weight loss or clinical improvement after MBS be described as a “suboptimal clinical response” or “suboptimal weight loss,” rather than “non-response” or an “inadequate” response to treatment. Similarly, consensus was reached on using “recurrent weight gain” for those who experience significant weight gain after initial postoperative weight loss.

Within the normal distribution of weight loss response to MBS, there is no specific magnitude of weight loss that clearly differentiates between treatment success and suboptimal response. There is some evidence that 20% of total body weight loss is associated with reduced cardiovascular risk [20, 21], so many clinicians and investigators have used this criterion to assess clinical responses to MBS. It is recognized that the magnitude of weight loss has widely different clinical effects in different patients, and a categorical definition of weight loss should not be used as the single determinant of the need for additional clinical intervention. Through this Delphi process, unanimous consensus was achieved on using the following reporting standards for “suboptimal initial clinical response” as initial total body weight loss < 20% or inadequate improvement in an obesity complication that was a significant indication for surgery and “recurrent weight gain” as recurrent weight gain > 30% or worsening of an obesity complication that was a significant indication for surgery. Given the different effectiveness of each MBS procedures [13, 14] and variable effects in different populations, these criteria should be applied to individual patients combined with expert clinical judgement.

As in the previous IFSO/WGO survey, ensuring adequate nutritional supplementation was strongly agreed upon, as was acceptance of the roles of AOM spanning virtually all clinical scenarios: as first-line therapy, in young and old patients, before and after MBS, and for both short-term and long-term use. Like other chronic diseases, the treatment of obesity should follow the principles of chronic disease management with a combination of treatment options. For obesity, combination therapies failed to progress in the past due to the lack of effective AOMs. With the increased availability of current available potent AOMs and in the pipeline, the practice of combination therapy will likely increase as MBS and AOMs can work in synergy. Conversely, amongst our experts panel, considerable disagreement/non-consensus was observed regarding the role of metabolic bariatric endoscopy due to a lack of strong scientific evidence in the literature, though the use of ESG, combined with lifestyle interventions, was consistently supported in patients with class I and II obesity, with or without obesity-related complications, and with class III obesity who either do not qualify for or choose not to pursue MBS.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that MBS is significantly more effective than dietary and lifestyle changes alone at inducing weight loss, reducing complications, comorbidities, and mortality, and improving patients’ overall quality of life [6, 8, 10, 11, 22,23,24]. Such reductions in complications and comorbidities include improvements in existing conditions and their prevention, including the prevention of various cardiometabolic diseases and cancers demonstrated also in multiple meta-analyses [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. But questions persist as to when MBS might be contraindicated and which procedure to select in different situations.

Worldwide, SG has become the most common MBS procedure performed, and our experts agreed that it is the most suitable choice for high-risk patients, pediatric patients, and seniors > 65. However, our experts also agreed that SG is less suitable in patients with certain obesity complications such as poorly controlled T2DM, GERD, or NASH. It was also the most commonly selected procedure for patients with a BMI ≥ 50 kg/m2 (by 66.7%), though no consensus was achieved. Voting on biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS) and sleeve gastrectomy single-anastomosis duodenoileostomy (SADI), the consensus was that suitable candidates include patients with a BMI > 50 kg/m2 and with severe or uncontrolled diabetes. However, those who undergo SADI-S will require surveillance and nutritional supplements for life. Voting on one-anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB), there was 100% consensus that a biliopancreatic limb ≥ 200 cm increases the risk of protein deficiency and that, unless otherwise contraindicated, both RYGB and OAGB are generally preferable to SG for adults with both T2DM and obesity.

Every expert consensus survey has the potential for bias, given that clinicians considered experts in a particular practice must utilize it to be considered experts. We tried to minimize such bias in numerous ways, including seeking the opinions of 17 multi-disciplinary non-surgeons with expertise in obesity management; by including experts from every continent; by taking several steps, like statement balancing, to minimize any bias inherent in the survey itself; and by assistance of an internationally recognized expert in Delphi surveys.

We acknowledge that consensus surveys rely on opinions, rather than experimentally generated data and represent level V evidence. On the other hand, our experts were all widely renowned experts in obesity management, most contributing extensively to obesity research, and were, thus, both highly familiar with and qualified to interpret their expansive knowledge of the literature. Ultimately, these consensus results will be used as an adjunct to a thorough literature review to guide clinical practice and assist in creating an algorithm to aid clinicians in their decisions when treating patients with obesity.

References

WOF. World Obesity Federation, World Obesity Atlas 2023 https://data.worldobesity.org/publications/WOF-Obesity-Atlas-V5.pdf.

NCD-Risk-Factor-Collaboration. Height and body-mass index trajectories of school-aged children and adolescents from 1985 to 2019 in 200 countries and territories: a pooled analysis of 2181 population-based studies with 65 million participants. Lancet. 2020;396(10261):1511–1524.

Abdullah A, Peeters A, de Courten M, et al. The magnitude of association between overweight and obesity and the risk of diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;89(3):309–19.

Powell-Wiley TM, Poirier P, Burke LE, et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143(21):e984–1010.

Peromaa-Haavisto P, Tuomilehto H, Kossi J, et al. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnoea among patients admitted for bariatric surgery. a prospective multicentre trial. Obes Surg. 2016;26(7):1384–90.

Aminian A, Wilson R, Al-Kurd A, et al. Association of bariatric surgery with cancer risk and mortality in adults with obesity. JAMA. 2022;327(24):2423–33.

Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, et al. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(17):1625–38.

Gronroos S, Helmio M, Juuti A, et al. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss and quality of life at 7 years in patients with morbid obesity: the SLEEVEPASS randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(2):137–46.

Aminian A, Al-Kurd A, Wilson R, et al. Association of bariatric surgery with major adverse liver and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with biopsy-proven nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. JAMA. 2021;326(20):2031–42.

Aminian A, Zajichek A, Arterburn DE, et al. Association of metabolic surgery with major adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity. JAMA. 2019;322(13):1271–82.

Arterburn DE, Olsen MK, Smith VA, et al. Association between bariatric surgery and long-term survival. JAMA. 2015;313(1):62–70.

Bray GA, Kim KK, Wilding JPH. Obesity: a chronic relapsing progressive disease process. A position statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obes Rev. 2017;18(7):715–23.

Peterli R, Wolnerhanssen BK, Peters T, et al. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss in patients with morbid obesity: the SM-BOSS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(3):255–65.

Salminen P, Helmio M, Ovaska J, et al. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss at 5 years among patients with morbid obesity: the SLEEVEPASS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(3):241–54.

Miras AD, Perez-Pevida B, Aldhwayan M, et al. Adjunctive liraglutide treatment in patients with persistent or recurrent type 2 diabetes after metabolic surgery (GRAVITAS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(7):549–59.

Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, et al. Bariatric Surgery survey 2018: similarities and disparities among the 5 IFSO chapters. Obes Surg. 2021;31(5):1937–48.

ASMBS-Clinical-Issues-Committee. Peri-operative management of obstructive sleep apnea. Surg Obes Relat Dis: Off J Amer Soc Bariatric Surg. 2012;8(3):e27–32.

Burger PM, Monpellier VM, Deden LN, et al. Standardized reporting of co-morbidity outcome after bariatric surgery: low compliance with the ASMBS outcome reporting standards despite ease of use. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2020;16(11):1673–82.

Keeney S, Hasson FHM. The Delphi technique in nursing and health research. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

Aminian A, Zajichek A, Tu C, et al. How much weight loss is required for cardiovascular benefits? Insights from a metabolic surgery matched-cohort study. Ann Surg. 2020;272(4):639–45.

King WC, Hinerman AS, Belle SH, et al. Comparison of the performance of common measures of weight regain after bariatric surgery for association with clinical outcomes. JAMA. 2018;320(15):1560–9.

Adams TD, Davidson LE, Hunt SC. Weight and metabolic outcomes 12 years after gastric bypass. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(1):93–6.

Ikramuddin S, Korner J, Lee WJ, et al. Lifestyle Intervention and medical management with vs without Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and control of hemoglobin A1c, LDL cholesterol, and systolic blood pressure at 5 years in the diabetes surgery study. JAMA. 2018;319(3):266–78.

Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes - 5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):641–51.

Chandrakumar H, Khatun N, Gupta T, et al. The effects of bariatric surgery on cardiovascular outcomes and cardiovascular mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cureus. 2023;15(2):e34723.

Nakanishi H, Teixeira AF, Matar RH, et al. Impact on mid-term health-related quality of life after duodenal switch: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2023;33(3):769–79.

Obeso-Fernández J, Millan-Alanis JM, Rodríguez-Bautista M, et al. Benefits of bariatric surgery on microvascular outcomes in adult patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis: Off J Amer Soc Bariatric Surg. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2023.02.024.

Pararas N, Pikouli A, Dellaportas D, et al. The protective effect of bariatric surgery on the development of colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(5).

Pontiroli AE, Centofanti L, Le Roux CW, et al. Effect of prolonged and substantial weight loss on incident atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2023;15(4):940.

Spiro C, Bennet S, Bhatia K. Meta-analysis of patient risk factors associated with post-bariatric surgery leak. Obes Sci Pract. 2023;9(2):112–26.

Sylivris A, Mesinovic J, Scott D, Jansons P. Body composition changes at 12 months following different surgical weight loss interventions in adults with obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Obes Rev. 2022;23(7): e13442.

Tang B, Zhang Y, Wang Y, et al. Effect of bariatric surgery on long-term cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Surg Obes Relat Dis: Off J Amer Soc Bariatric Surg. 2022;18(8):1074–86.

Wilson RB, Lathigara D, Kaushal D. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of bariatric surgery on future cancer risk. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(7):6192.

Yang W, Zhan M, Li Z, Sun X, et al. Major adverse cardiovascular events among obese patients with diabetes after metabolic and bariatric surgery: a meta-analysis of matched cohort and prospective controlled studies with 122,361 participates. Obes Surg. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-023-06634-y.

Acknowledgements

We thank Manuela Mazzarella for her expert guidance and invaluable help throughout this process from start to finish, and to both Ilaria Regio and Stefania Acanfora for their assistance both before and throughout the congress in Hamburg.

IFSO Experts Panel of Pub-Med Indexed Collaborative authors (in alphabetical order, all participated in the consensus meeting, Delphi voting, critical reviewing of the manuscript before submission, and all confirmed their collaborative authorship and approval of the manuscript submission):

Barham K. Abu Dayyeh (Department of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA), Nasreen Alfaris (Obesity Endocrine and Metabolism Center King Fahad Medical City, Riyadh, KSA), Aayeed Al Qahtani (New You Medical Center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia), Barbara Andersen (Austrian Obesity Alliance 1070 Vienna, Austria), Luigi Angrisani (University of Naples “Federico II” Department of Public Health, Naples, Italy), Ahmad Bashir (GBMC at Jordan Hospital, Amman, Jordan), Rachel L. Batterham (Centre for Obesity Research University College London, University College London Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK), Estuardo Behrens (New Life Center, Guatemala City, Guatemala), Mohit Bhandari (Mohak Bariatrics & Robotics, Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India), Dale Bond (Departments of Surgery and Research Hartford Hospital/HealthCare Hartford, CT, USA), Jean-Marc Chevallier (Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, University of Paris, France), Ricardo V. Cohen (Center for the Treatment of Obesity and Diabetes, Hospital Alemao Oswaldo Cruz, São Paulo, Brazil), Dror Dicker (Internal Medicine D & Obesity Clinic, Hasharon Hospital-Rabin Medical Center, Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel), Claudia K. Fox (University of Minnesota, Medical School Center for Pediatric Obesity Medicine, Minneapolis, MN USA), Pierre Garneau (Hôpital du Sacré-Coeur de Montréal, Canada), Khaled Gawdat (Ain-Shams School of Medicine, Cairo, Egypt), Ashraf Haddad (Gastrointestinal, Bariatric, and Metabolic Center (GBMC) Amman, Jordan), Jacqués Himpens (Department of Visceral Surgery Delta CHIREC Hospital Brussels, Belgium), Thomas Inge (Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA), Marina Kurian (NYU Langone Health, New York, NY, USA), Silvia Leite Faria (Gastrocirurgia de Brasília, Brasilia, Brazil), Guilherme Macedo (Centro Hospitalar de São João, Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Porto, Portugal), Alexander Dimitri Miras (School of medicine, Ulster university, Derry, UK), Violeta Moize (Unit of Obesity, Department of Endocrinology Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, Spain), Francois Pattou (Department of Endocrine and Metabolic surgery, CHU Lille, University of Lille, Inserm, France), Luis Poggi (Clinica Anglo Americana Lima, Peru), Jaime Ponce (Metabolic and Bariatric Care CHI Memorial Hospital, Chattanooga, Tennessee, USA), Almino Ramos (GastroObesoCenter Institute—Advanced Institute for Metabolic Optimization, Sao Paulo, Brazil), Francesco Rubino (School of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Medicine and Sciences, King’s College London, UK ), Andrés Sanchez-Pernaute (Department of Surgery Complutense University of Madrid, Spain), David Sarwer (Center for Obesity Research and Education at the College of Public Health at Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA), Arya M. Sharma (Department of Medicine, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada), Christine Stier (Division of Interdisciplinary Endoscopy, and Clinic for General and Visceral Surgery, Mannheim University Hospital Mannheim, Germany), Christopher Thompson (Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Endoscopy Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA), Josep Vidal (Obesity Unit Department of Endocrinology, Hospital Clínic, Barcelona, Spain), Tarissa Beatrice Zanata Petry (Center for the Treatment of Obesity and Diabetes, Hospital Alemao Oswaldo Cruz, São Paulo, Brazil).

Funding

Open Access funding provided by University of Turku (including Turku University Central Hospital).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. Informed consent does not apply.

Conflict of Interest

Paulina Salminen reports lecture fees from Novo Nordisk.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Key Points

• The value of an international multidisciplinary expert consensus in obesity management enabled the validation of standardized definitions and reporting standards applicable to the entire medical community treating patients with obesity facilitating research and clinical practice of MBS.

• Consensus was reached on most MBS issues, and areas of non-consensus were identified, assisting in clinical practice guidelines for the management of obesity.

• Inadequate weight loss or an unusually modest improvement in a clinically significant obesity complication was unanimously defined as “suboptimal initial response” (TWL <20%) and significant weight gain after initial postoperative weight loss was defined as “recurrent weight gain” (gaining >30% of the initial weight loss or worsening of an obesity complication).

• Sleeve gastrectomy was considered the most suitable choice for high-risk patients, pediatric patients, and patients >65 years old.

• Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and one-anastomosis gastric bypass are generally preferable to sleeve gastrectomy for adults with obesity and type 2 diabetes, unless otherwise contraindicated.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (MOV 11854 KB)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Salminen, P., Kow, L., Aminian, A. et al. IFSO Consensus on Definitions and Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity Management—an International Delphi Study. OBES SURG 34, 30–42 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-023-06913-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-023-06913-8