Abstract

Rubber [Hevea brasiliensis (Willd. ex A.Juss.) Müll.Arg.] plantations are the largest cultivated forest type in tropical China. Returning organic materials to the soil will help to maintain the quality and growth of rubber trees. Although many studies have demonstrated that organic waste materials can be used to improve soil fertility and structure to promote root growth, few studies have studied the effects of organic amendments on soil fertility and root growth in rubber tree plantations. Here, bagasse, coconut husk or biochar were applied with a chemical fertilizer to test their effects on soil properties after 6 months and compared with the effects of only the chemical fertilizer. Results showed that the soil organic matter content, total nitrogen, available phosphorus and available potassium after the chemical fertilizer (F) treatment were all significantly lower than after the chemical fertilizer + bagasse (Fba), chemical fertilizer + coconut husk (Fco) or chemical fertilizer + biochar (Fbi) (p < 0.05). Soil pH in all organic amendments was higher than in the F treatment, but was only significantly higher in the Fbi treatment. In contrast, soil bulk density in the F treatment was significantly higher than in treatments with the organic amendments (p < 0.05). When compared with the F treatment, soil root dry mass increased significantly by 190%, 176% and 33% in Fba, Fco and Fbi treatments, respectively (p < 0.05). Similar results were found for root activity, number of root tips, root length, root surface area and root volume. Conclusively, the application of bagasse, coconut husk and biochar increased soil fertility and promoted root growth of rubber trees in the short term. However, bagasse and coconut husk were more effective than biochar in improving root growth of rubber trees.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Tree root systems are vitally important for the proper functioning of forest ecosystems because of their pivotal roles in the absorption of soil nutrients and water, soil organic matter stock, and for maintaining plant growth, tree stability and stem straightness (Lindström and Rune 1999; Collins and Bras 2007; Xi et al. 2011; Pransiska et al. 2016; Bo et al. 2018; Wang and Xie 2018). Fine roots (diameter < 2 mm) are the most active segments of root systems and respond rapidly to variations in the soil environment (Hendrick and Pregitzer 1992; Lukac and Godbold 2010; Montagnoli et al. 2012; Jha 2018; Liu et al. 2018). For instance, fine root biomass rapidly increased when soil moisture increased after drought. Soil nutrient levels may also influence the growth and turnover rates of fine roots and cause plant roots to grow deeper (McConnaughay and Coleman 1999). Fine root growth also could be induced in soil with relatively low pH in with different levels of acidity (Helmisaari and Hallbäcken 1999; Assefa et al. 2017).

The natural rubber of the rubber tree, a strategic resource of modern times (Langenberger et al. 2017), is an important raw material for many rubber-based industries and widely used for military, transport, medical purposes and others. The rubber tree is one of the main economic species available in many tropical countries in Asia, South America and Africa. For example, the natural rubber industries contributed approximately 4.69% of the country’s GDP in Malaysia in 2013, with USD 101.19 billion contribution to the national export revenue (Sharib and Halog 2017). During the 1950s, the Chinese government greatly expanded rubber production by converting a large portion of the tropical rain forests of China into rubber plantations (Zhang et al. 2007a, b). The variety of rubber trees that have been widely planted on Hainan Island and in Yunnan and Guangdong Provinces cover approximately 1.07 million ha and provide high economic value (Zhang et al. 2007a, b; Qi et al. 2013). Rubber plantations currently cover approximately 47% of the total planting areas of Hainan Island and are the largest agricultural ecosystem on this island of southern China (Lin et al. 2016). Fertilization is one of the most important practices to maintain tree growth and rubber yield because root morphology depends significantly on nutrient availability (Fransen et al. 1998). Trees increase their number of fine roots to absorb more soil nutrients (Bo et al. 2018). Normally, rubber planters are encouraged to apply chemical fertilizer and organic materials to an excavated fertilization cave (typically 100–200 cm long × 60 cm wide × 40 cm deep) between rows by taking advantage of the physiological plasticity of roots to obtain nutrients. The fine root biomass of rubber in these fertilization caves accounts for 94.7% of the total fine root biomass (Liu et al. 2006).

Nevertheless, due to an inadequate input of fertilizers and organic materials, the content of organic matter, total nitrogen and available potassium in soil (0–40 cm) of most rubber (H. brasiliensis (Willd. ex A.Juss.) Müll.Arg.) plantations has decreased by 41–48% compared with the beginning of the extensive expansion of rubber plantations on Hainan Island in the 1950s (Wang et al. 2013; Guo et al. 2015). To maintain the soil quality, organic amendments must be adopted in the management of rubber plantations (Zhang et al. 2007a, b), one or two applications a year (at least 50 kg per cave) are strongly encouraged as a standard part of rubber tree cultivation (Lin et al. 2006). However, many rubber planters have not completely implemented this critical management practice because they lack the organic materials. They apply the most convenient and readily available source, the weeds that grow in the inter-row space of rubber trees or near rubber plantations, but the amounts are often lower than recommended (Fan 2005). Incorporating organic materials such as crop straw, arboreal litter, bagasse, mushroom residue, biochar increases soil fertility, improves soil structure (Yadav and Prasad 1992; Nardi et al. 2004; Su et al. 2006; Long et al. 2015; Azeez 2018), and induces root growth and water absorption by plants in other agricultural systems (Gill et al. 2009). However, the effects of organic amendments on soil fertility and rubber root growth are not well understood. Therefore, the main objective of this study was to determine the effects of organic amendments on soil physicochemical properties and root growth of rubber trees in a short-term study of 6 months. Because coconut trees and sugarcane are also widely planted on Hainan Island, coconut husks and bagasse are readily available. Biochar has been widely used to grow many crops and has many benefits including improving soil quality and plant growth (Van Zwieten et al. 2010). Thus, these three types of organic amendments were tested for their effects on soil fertility and promoting root growth of rubber trees in the current study to provide a basis for recommending policies to promote sustainable land management for fertilizing rubber plantations.

Materials and methods

Study site

The study site (19°32′55″ N, 109°28′30″ E) is located on the experimental farm of the Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences in Danzhou City, the largest rubber production base of Hainan Province, China. The topography is hilly. The elevation ranges from 0.5 to 659.2 m. The local tropical monsoon climate has a mean annual temperature of 23.2 °C and a mean annual precipitation of 1600 mm with > 85% in May to October. The experiment was carried out from January to June 2015. The silty clay loam is an acid soil (pH 4.73) and contained 8.85 g kg−1 organic matter, 0.73 g kg−1 total nitrogen (N), 15.11 mg kg−1 available phosphorous and 55.03 mg kg−1 available potassium (K) at the start of the experiment.

Experimental design

Rubber [H. brasiliensis (Willd. ex A.Juss.) Müll.Arg.] trees were planted at the recommended density (3 × 7 m, 480 plants⋅ha−1) in 1996. The experimental site stands on a gentle slope of about 6°. Tree rows were oriented approximately east to west to prevent soil and water loss. Trees averaged 15 to 18 m tall. The area between the rows was occasionally mown to limit the growth of competing vegetation. Tapping of the rubber trees was initiated in 2003. Rubber tree clone CATAS 7-33-97 was used for the study.

Chemical fertilizer and organic materials were added to the excavated fertilization caves between rows according to field management practice with six trees for each treatment as follows: (1) conventional specialized chemical fertilizer (F) (2) chemical fertilizer + bagasse (Fba) (3) chemical fertilizer + coconut husk (Fco) and (4) chemical fertilizer + biochar (Fbi). Six trees in three adjoining rows were treated without the use of a fertilization cave. The fine roots of rubber trees in plantation arbors are mainly distributed in the 0–30 cm soil layer (He and Huang 1987). In all treatments, two holes (20 cm long × 20 cm wide × 30 cm deep) were excavated 1 m from a rubber tree in the inter-row space without excavating a fertilization cave (Fig. 1). Visible roots and stones were removed from the excavated soils, which were then allowed to air dry. Biochar was made from peanut shells heated at 350–500 °C for 30 mi. The biochar was crushed and sieved through a 2-mm sieve before application. The bagasse and coconut husk particles (less than 5 mm in diameter) were used directly. For the Fba, Fco and Fbi treatments, nutrients were incorporated into the air-dried soil as follows. The basic properties of amendments are shown in Table 1. The amended soil (soil to amendment, 9:1 by mass) was mixed with 59.2 g of a special chemical fertilizer (N–P2O5–K2O = 14:7:9); the soils were then returned to the original holes. For the F treatment, the soil was mixed only with the chemical fertilizer at 0.148 g cm−2), the conventional rate applied in February or March. In all holes, three profiles were barricaded with felt paper to keep the roots in the hole except for the profile of the nearest rubber tree. The experiments were set up in January, and roots and soil in each hole were sampled in July.

Sampling and measurements

Root and soil samples were collected 6 months after the amendments to analyze soil chemical properties and root morphology in one of the two holes of each tree (Fig. 1). Briefly, the soil outside of the felt paper was excavated. Then the felt paper was carefully removed. The soil for each sample was separated carefully from the roots with toothpicks and stored in a plastic bag. The roots for each sample were cut and put in a plastic bag. In the second hole (Fig. 1), soil (0–5 cm) was sampled with a cutting ring to determine soil bulk density. The root sample from this hole was collected to measure root activity. Each root sample was stored in a cool box containing ice packs and then transported with the soil to the laboratory. Root activity and soil bulk density were determined immediately after transporting samples from the field. The root samples used for morphological analysis and determination of soil chemical properties were stored in a refrigerator under 4 °C. Then they were removed and analyzed the next day.

The separated soil was used to analyze soil organic matter (SOM), total nitrogen (TN), available phosphorus (AP), available potassium (AK) and soil pH. The SOM and TN were determined using the potassium dichromate–wet combustion procedure and the Kjeldahl distillation method, respectively (Bao 2000). Available potassium was extracted with 1.0 mol L–1 ammonium acetate solution and measured according to Page et al. (1982) and Bao (2000). Available phosphorus was extracted with 0.5 mol L–1 NaHCO3 and then determined calorimetrically by the molybdate–ascorbic acid method (Olsen et al. 1954; Murphy and Riley 1962; Bao 2000). Soil pH was determined using a 12.5 soil to water ratio (Bao 2000).

The root samples were washed in a 150-μm sieve and then scanned to obtain images for analysis of root tip of total root (tips L–1), length (m m–3), surface area (m2m–3) and volume (cm3 m–3) of total root and fine root (< 2 mm) in WinRHIZO (Regent Instruments, Quebec, Canada). Roots were then wrapped in filter paper and measured after drying for 3 days at 70 °C for dry root mass (μg cm–3).

Soil transferred from the cutting ring was dried at 105 °C for measurement of soil bulk density (g cm−3). Root activity (μg g–1 h–1) was determined by the triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) reduction method, as described by Li (2000).

Statistical analysis

Significant differences in root morphology, soil physical and chemical properties were identified using analysis of variance by least significant difference calculations and SPSS software (SPSS 17.0, Chicago, IL, USA) at p < 0.05 in most cases. Relationships between soil properties and root dry mass density were determined using Pearson’s correlation analysis.

Results

Soil physical and chemical properties

Soil properties after the different treatments are shown in Fig. 2. The SOM content (46.35 g kg–1) in the Fbi treatment was significantly higher than after the Fco (32.11 g kg–1) and Fba (27.82 g kg–1) treatments. Without the organic amendment (the F treatment), the SOM (10.04 g kg–1) was significantly lower than the Fbi, Fco and Fba treatments (p < 0.05). Similar trends were found for the contents of TN, AP and AK after the different treatments. The Fbi treatment had the highest pH (6.20), significantly higher than in the Fba, Fco and F treatments (p < 0.05). The rank of bulk density was F > Fbi > Fco > Fba with significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05).

Soil physicochemical properties after different soil treatments. Different letters above bars indicate significant differences between treatments for that property (p < 0.05). Treatments: chemical fertilizer only (F), chemical fertilizer + bagasse (Fba), chemical fertilizer + coconut husk (Fco) and chemical fertilizer + biochar (Fbi). Error bars indicate standard errors (n = 6)

Root dry mass density and its relationship with soil properties.

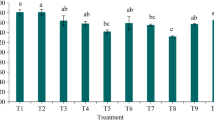

The addition of organic materials significantly improved the root growth of rubber trees compared with the application of chemical fertilizer alone. The Fba treatment resulted in the highest root dry mass density (597.5 μg cm−3), followed by the Fco and Fbi treatments (Fig. 3). Root dry mass density in the Fba, Fco and Fbi treatments increased significantly by 190%, 176% and 33% when compared with the F treatment (p < 0.05). An analysis of the linear relationship showed that growth was significantly related to soil bulk density among treatments (Table 2).

Root dry mass density after different soil treatments. Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments for that property (p < 0.05). Treatments: chemical fertilizer only (F), chemical fertilizer + bagasse (Fba), chemical fertilizer + coconut husk (Fco) and chemical fertilizer + biochar (Fbi). Error bars indicate standard errors (n = 6)

Root activity and number of root tips

The root activity and number of root tips produced in different treatments are shown in Fig. 4. The rank of root activity was Fbi > Fco > Fba > F and for number of root tips, Fco > Fba > Fbi > F. Root activity after Fba, Fco and Fbi treatments was 1.8-, 1.9- and 1.4-fold higher than in F treatment and for number of root tips was 3.3-, 4.6- and 4.9-fold higher (p < 0.05).

Root activity (A) and root number of root tips (B) after different treatments. Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments for that property (p < 0.05). Treatments: chemical fertilizer only (F), chemical fertilizer + bagasse (among), chemical fertilizer + coconut husk (Fco) and chemical fertilizer + biochar (Fbi). Error bars indicate standard errors (n = 6)

Root length, surface area and volume

Root length, surface area and volume of total root and fine root from different treatments are presented in Fig. 5. The range for fine root length, surface area and volume was 3002–7254 m m–3, 5.3–13.6 m2 m–3 and 943–2480 cm3 m–3, respectively, accounting for 96.2%–97.5%, 76.6%–80.7% and 72.6%–81.1% of the total root. The root length, surface area and volume of total root and fine root in the Fba and Fco treatments were significantly higher than in the Fbi and F treatments. The root length, surface area and volume in the Fbi treatment were also higher than in the F treatment, but only the total root length, fine root length and fine root volume were significantly higher than in the F treatment (p < 0.05).

Length, surface area and volume of total and fine roots after different treatments. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05). Note: treatments included chemical fertilizer only (F), chemical fertilizer + bagasse (Fba), chemical fertilizer + coconut husk (Fco) and chemical fertilizer + biochar (Fbi). Error bars indicate standard errors (n = 6)

Discussion

Soil fertility and organic material return

Intensive cultivation of rubber plantations often causes a significant loss of soil fertility (Zhang et al. 2007a, b). As a consequence, a large supply of organic material is needed to maintain high levels of crop productivity and soil organic matter and improve some soil properties (Montemurro et al. 2007). Crop residues and organic wastes are usually returned to fields as nutrient source and improve soil physical properties (Siddiqui and Akhtar 2008; Párraga-Aguado et al. 2017). In this study, SOM, TN, AP and AK content increased by 63–362% in treatments with organic amendments when compared with the F treatment (Fig. 2). These results are consistent with many studies that have shown that organic amendments increase soil fertility such as SOM, TN, nitrate–N, AP and AK content (Akhtar and Mahmood 1996; Cai and Qin 2006; Chan et al. 2007; Long et al. 2015; Mohammadi Torkashvand et al. 2015; Guo et al. 2016; Seleiman and Kheir 2018; Wrobel-Tobiszewska et al. 2018). As Table 1 shows, the nutrient level of the three organic materials were in the order of biochar > coconut husk > bagasse. The soil fertility order of the amendments was similar (Fig. 2). Thus, the soil nutrients are highly dependent on the nutrient richness of the organic material. Conclusively, the addition of bagasse, coconut husk, and biochar resulted in significantly increased soil fertility as hypothesized.

Soil bulk and pH influenced by organic amendments

Organic amendments change the trophic structure, bulk density and pH of soil (Akhtar and Mahmood 1996). Soil bulk density tends to decrease probably because of the presence of nondecomposed organic materials in the soil (Jones et al. 2011; Mohammadi Torkashvand et al. 2015), while variation in pH depends on the type and amount of the amendment (Montemurro et al. 2007; Dharmakeerthi et al. 2012; Luo et al. 2014). Consistently, the bulk density after the amendments was significantly lower than after the F treatment. In addition, the different amendments had significantly different effects on bulk density (Fig. 2). In terms of pH, the Fba and Fco treatments did not significantly change soil pH compared with the F treatment, consistent with the results of a previous study (Montemurro et al. 2007). The pH of biochar was higher than that of bagasse and coconut husk (Table 1), consistent with the findings of Luo et al. (2014), whose results showed that the pH of acid soil (pH 3.7) and alkaline soil (pH 7.6) increased by 0.76–1.50 and 0.23–0.99 after application of 60–76 g kg−1 of biochar to soil, respectively, the pH increased significantly (by 1.58) after the Fbi treatment (Fig. 2). High content of soil exchangeable aluminum and acid are major contributors to soil acidity in rubber plantation (Sun et al. 2016); thus, a decrease in their content after the Fbi treatment could increase soil pH. This possibility was supported by the finding of Wu et al. (2017) that the addition of biochar (45 g kg−1 soil) to soil in rubber plantations remarkably decreases the soil exchangeable aluminum and acid content, after a significant increase of soil pH during a 70-d period.

Effects of organic material addition on root growth

If managed properly, organic waste material can be used to increase soil fertility and improve soil structure to promote root growth (Siddiqui and Akhtar 2008). Many studies have shown that root biomass (Montemurro et al. 2007; Haghighi et al. 2016); number of root tips (Guo et al. 2016); root activity (Zhu et al. 2002); and root length, surface area and volume (Guo et al. 2016; Tian et al. 2017) increase after the addition of organic waste. These findings are consistent with those of the current study (Figs. 3–5).

Although biochar application has increased plant crop growth in natural woodland and cultivated fields (He and Huang 1987; Guo et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2017; Razaq et al. 2017), here the Fba and Fco treatments had stronger positive effects than the Fbi treatment on root growth, although soil fertility after the Fbi treatment was higher than after the Fba or Fco treatments. Increased soil fertility did not always promote root growth, indicating that other factors are more important. The linear analysis in the present study showed that bulk density was the most important factor affecting root growth among treatments (Table 2). However, when the Fbi treatment was excluded, significant relationships were observed between root growth and SOM, TN, AP and bulk density, in contrast to positive nonsignificant relationships between growth and both AK and pH among the F, Fba and Fco treatments (data not shown). Although root growth and pH were weakly related, pH is presumed to be very important, in addition to soil bulk density, in controlling root growth of rubber trees. Considering that the optimal pH for rubber trees grown in acid soil is in the range of 4.5–5.5 (He and Huang 1987), the pH of the Fbi treatment (10% biochar, w/w; pH 6.28) is far above the optimal, in contrast to the pH of the F, Fba and Fco treatments (pH 4.62–4.83; Fig. 2) within the optimal range for growth. Thus, root growth was likely suppressed by the Fbi treatment because of the higher soil pH in the short term even though the soil bulk density and the high soil nutrient level were within the optimal range for root growth (Wang 2010). This possibility is supported by Dharmakeerthi et al. (2012), who showed that the root dry mass of rubber plants decreased when the soil was treated with 1% and 2% (w/w) biochar during the 8-month nursery period. Therefore, the addition of bagasse, coconut husk and biochar significantly promoted root growth of rubber tree as we hypothesized. Nevertheless, the addition of different organic materials may result in different positive effects on root growth. The addition of bagasse and coconut husk had obviously higher positive effects on root growth than the biochar. As a result, bagasse and coconut husk are more suitable than biochar for rubber plantations, and their addition every year should be encouraged to improve soil properties and root growth in the short term. In further studies, experiments should be designed to examine the long-term effects of returning these amendments on soil fertility and root growth of H. brasiliensis.

Conclusions

The addition of bagasse, coconut husk and biochar accompanied by chemical fertilizer lowered soil bulk density by 7.4%–40.2% and increased soil fertility by 177–362% for soil organic matter, 102–163% for total nitrogen, 39–70% for available phosphorus and 5–63% for available potassium, respectively, compared to the chemical fertilizer treatment in the short term. In turn, root biomass increased by 33–190%. Biochar was more effective than bagasse or coconut husks in improving soil fertility. However, bagasse and coconut husks were more effective than biochar in improving root growth probably because biochar significantly increased soil pH by 1.58, which probably suppressed root growth. Thus, the properties of the organic amendment and the optimal soil pH for rubber tree need to be considered when choosing an amendment to improve soil fertility and root growth of rubber trees.

References

Akhtar M, Mahmood I (1996) Organic soil amendments in relation to nematode management with particular reference to India. Integr Pest Manag Rev 1(4):201–215

Assefa D, Rewald B, Sandén H, Godbold DL (2017) Fine root dynamics in Afromontane forest and adjacent land uses in the Northwest Ethiopian Highlands. Forests 8(7):249

Azeez JO (2018) Recycling organic waste in managed tropical forest ecosystems: effects of arboreal litter types on soil chemical properties in Abeokuta, southwestern Nigeria. J For Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-018-0753-z

Bao SD (2000) Soil and agricultural chemistry analysis. China Agriculture Press, Beijing (in Chinese)

Bo HJ, Wen CY, Song LJ, Yue YT, Nie LS (2018) Fine-root responses of Populus tomentosa forests to stand density. Forests 9(9):562

Cai ZC, Qin SW (2006) Dynamics of crop yields and soil organic carbon in a long-term fertilization experiment in the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain of China. Geoderma 136(3–4):708–715

Chan KY, Van Zwieten L, Meszaros I, Downie A, Joseph S (2007) Agronomic values of greenwaste biochar as a soil amendment. Aus J Soil Res 45:629–634

Collins DBG, Bras RL (2007) Plant rooting strategies in water-limited ecosystems. Water Resour Res 43(6):W6407

Dharmakeerthi RS, Chandrasiri JAS, Edirimanne VU (2012) Effect of rubber wood biochar on nutrition and growth of nursery plants of Hevea brasiliensis established in an Ultisol. Springerplus 1(1):84

Fan HX (2005) The construction and implication of natural rubber and sugarcane production function in Hainan Province. South China University of Tropical Agriculture, Danzhou (in Chinese)

Fransen B, de Kroon H, Berendse F (1998) Root morphological plasticity and nutrient acquisition of perennial grass species from habitats of different nutrient availability. Oecologia 115(3):351–358

Gill JS, Sale PWG, Peries RR, Tang C (2009) Changes in soil physical properties and crop root growth in dense sodic subsoil following incorporation of organic amendments. Field Crop Res 114(1):137–146

Guo PT, Li MF, Luo W, Tang QF, Liu ZW, Lin ZM (2015) Digital mapping of soil organic matter for rubber plantation at regional scale: an application of random forest plus residuals kriging approach. Geoderma 237–238:49–59

Guo GX, Pan ZY, Peng S (2016) Effect of biochar on the growth of Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf. seedlings in Gannan acidic red soil. Soil Sci Plant Nutr 62(2):194−200

Haghighi M, Barzegar MR, Da Silva JAT (2016) The effect of municipal solid waste compost, peat, perlite and vermicompost on tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum L.) growth and yield in a hydroponic system. Int J Recy Org Waste Agric 5(3):231−242

He K, Huang ZD (1987) Rubber tree cultivation in tropical north region. Guangdong science and technology press, Guangzhou (in Chinese)

Helmisaari and Hallbäcken, 1999 Helmisaari H, Hallbäcken L (1999) Fine-root biomass and necromass in limed and fertilized Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst.) stands. For Ecol Manag 119(1–3):99–110

Hendrick RL, Pregitzer KS (1992) The demography of fine roots in a northern hardwood forest. Ecology 73(3):1094–1104

Jha KK (2018) Biomass production and carbon balance in two hybrid poplar (Populus euramericana) plantations raised with and without agriculture in southern France. J For Res 29(6):1689–1701

Jones BE, Haynes RJ, Phillips IR (2011) Influence of organic waste and residue mud additions on chemical, physical and microbial properties of bauxite residue sand. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 18(2):199–211

Langenberger G, Cadisch G, Martin K, Min S, Waibel H (2017) Rubber intercropping: a viable concept for the 21st century? Agrofor Syst 91(3):577–596

Lin WF, Wu JL, Chen JX. Liu YQ, Xie GS (2006) Technical regulations for rubber tree cultivation. Ministry of agriculture of the People's Republic of China. NY/T 221−2006 (in Chinese)

Lin QH, Li H, Li BG, Guo PT, Luo W, Lin ZM (2016) Assessment of spatial uncertainty for delineating optimal soil sampling sites in rubber tree management using sequential indicator simulation. Ind Crop Prod 91:231–237

Lindström A, Rune G (1999) Root deformation in plantations of container-grown Scots pine trees: effects on root growth, tree stability and stem straightness. Plant Soil 217(1/2):29–37

Liu JL, Liu JY, Luo W, Lin ZM, Cha ZZ, Lin QH, Chen SC (2006) Distribution of nutrient roots of rubber trees close to manure hole in rubber plantation. Chin J Trop Crops 27(3):5–10 (in Chinese)

Liu L, Wang YF, Yan XW, Li JW, Jiao NY, Hu SJ (2017) Biochar amendments increase the yield advantage of legume-based intercropping systems over monoculture. Agric Ecosyst Environ 237:16–23

Liu S, Luo D, Yang HG, Shi ZM, Liu QL, Zhang L, Kang Y (2018) Fine root dynamics in three forest types with different origins in a subalpine region of the Eastern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Forests 9(9):517

Long P, Sui P, Gao WS, Wang BB, Huang JX, Yan LL, Yan P, Zou JX, Chen YQ (2015) Aggregate stability and associated C and N in a silty loam soil as affected by organic material inputs. J Integr Agric 14(4):774–787

Lukac M, Godbold DL (2010) Fine root biomass and turnover in southern taiga estimated by root inclusion nets. Plant Soil 331(1–2):505–513

Luo Y, Zhao XR, Li GT, Zhao LX, Meng HB, Lin QM (2014) Effect of biochar on mineral nitrogen content in soils with different pH values. Trans Chin Soc Agric Eng 30(19):166–173 (in Chinese)

McConnaughay KDM, Coleman JCS (1999) Biomass allocation in plants: Ontogeny or optimality? A test along three resource gradients. Ecology 80(8):2581–2593

Mohammadi Torkashvand A, Alidoust M, Mahboub Khomami A (2015) The reuse of peanut organic wastes as a growth medium for ornamental plants. Int J Recy Org Waste Agric 4(2):85–94

Montagnoli A, Terzaghi M, Di Iorio A, Scippa GS, Chiatante D (2012) Fine-root morphological and growth traits in a Turkey-oak stand in relation to seasonal changes in soil moisture in the Southern Apennines, Italy. Ecol Res 27(6):1015–1025

Montemurro F, Maiorana M, Convertini G, Ferri D (2007) Alternative sugar beet production using shallow tillage and municipal solid waste fertiliser. Agron Sustain Dev 27(2):129–137

Murphy J, Riley JP (1962) A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters. Anal Chim Acta 27:31–36

Nardi S, Morari F, Berti A, Tosoni M, Giardini L (2004) Soil organic matter properties after 40 years of different use of organic and mineral fertilisers. Eur J Agron 21(3):357–367

Olsen SR, Cole CV, Watanabe FS, Dean L A (1954) Estimation of available phosphorous in soils by extraction with sodium bicarbonate. USDA Circular No. 939, US Government Printing Office, Washington

Page AL, Miller RH, Keeney DR (1982) Methods of soil analysis. Part 2. In: Chemical and microbiological properties. American Society of America, Soil Science Society America, Madison

Párraga-Aguado I, Alcoba-Gómez P, Conesa HM (2017) Suitability of a municipal solid waste as organic amendment for agricultural and metal(loid)-contaminated soils: effects on soil properties, plant growth and metal(loid) allocation in Zea mays L. J Soils Sediments 17:2469–2480

Pransiska Y, Triadiati T, Tjitrosoedirjo S, Hertel D, Kotowska MM (2016) Forest conversion impacts on the fine and coarse root system, and soil organic matter in tropical lowlands of Sumatera (Indonesia). For Ecol Manag 379:288–298

Qi DL, Wang XQ, Zhang ZY, Huang YQ (2013) Current situation of Chinese natural rubber industry and development suggestions. Chin J Trop Agric 33(2):79–87 (in Chinese)

Razaq M, Salahuddin Shen HL, Sher H, Zhang P (2017) Influence of biochar and nitrogen on fine root morphology, physiology, and chemistry of Acer mono. Sci Rep 7(1):5367

Seleiman MF, Kheir A (2018) Saline soil properties, quality and productivity of wheat grown with bagasse ash and thiourea in different climatic zones. Chemosphere 193:538–546

Sharib S, Halog A (2017) Enhancing value chains by applying industrial symbiosis concept to the Rubber City in Kedah. Malaysia J Clean Prod 141:1095–1108

Siddiqui ZA, Akhtar MS (2008) Effects of organic wastes, Glomus intraradices and Pseudomonas putida on the growth of tomato and on the reproduction of the Root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Phytoparasitica 36(5):460–471

Su YZ, Wang F, Suo DR, Zhang ZH, Du MW (2006) Long-term effect of fertilizer and manure application on soil-carbon sequestration and soil fertility under the wheat-wheat-maize cropping system in northwest China. Nutr Cycl Agroecosyst 75(1–3):285–295

Sun HD, Liu B, Wu BS, Wei JS, He P, Gao L, Wu M (2016) Characteristics and cause of soil acidification in the rubber plantation. J Northwest Forestry University 31(2):49–54 (in Chinese)

Tian N, Fang SZ, Yang WX, Shang XL, Fu XX (2017) Influence of container type and growth medium on seedling growth and root morphology of Cyclocarya paliurus during nursery culture. Forests 8(10):387

Van Zwieten L, Kimber S, Morris S, Chan KY, Downie A, Rust J, Joseph S, Cowie A (2010) Effects of biochar from slow pyrolysis of papermill wasteon agronomic performance and soil fertility. Plant Soil 327(1/2):235–246

Wang Q (2010) Effects of soil compaction on root-soil system and development in maize. Henan Agricultural University, Zhengzhou (in Chinese)

Wang YJB, Xie Z (2018) The effects of dynamic root distribution on land-atmosphere carbon and water fluxes in the Community Earth System Model (CESM1.2.0). Forests 9(9):172

Wang DP, Wang XQ, Chen J, He P, Wei JS (2013) Current status of nutrient management in Hainan rubber planting areas and improvement strategies. Chin J Trop Agric 33(9):22–27 (in Chinese)

Wrobel-Tobiszewska A, Boersma M, Sargison J, Adams P, Singh B, Franks S, Birch CJ, Close DC (2018) Nutrient changes in potting mix and Eucalyptus nitens leaf tissue under macadamia biochar amendments. J For Res 29(2):383–393

Xi BY, Wang Y, Jia LM, Si J, Xiang DK (2011) Property of root distribution of triploid Populus tomentosa and its relation to root water uptake under the wide-and-narrow row spacing scheme. Acta Ecol Sin 31(1):47–57 (in Chinese)

Yadav RL, Prasad SR (1992) Conserving the organic matter content of the soil to sustain sugarcane yield. Exp Agric 28(01):57

Zhang H, Zhang GL, Zhao YG, Zhao WJ, Qi ZP (2007a) Chemical degradation of a Ferralsol (Oxisol) under intensive rubber (Hevea brasiliensis) farming in tropical China. Soil Till Res 93(1):109–116

Zhang M, Xian-Hui FU, Feng WT, Zou X (2007b) Soil organic carbon in pure rubber and tea-rubber plantations in South-western China. Trop Ecol 48(2):201–207

Zhu L, Zhang CL, Shen QR (2002) A study on the effect of the rice straw and other organic materials on the root activity and the activity of Nitratase and ATPase of cropping cucumber. Chin Agric Sci Bull 18(1):17–19 (in Chinese)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Project funding: The work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2018YFD0201100) and the Fundamental Research Funds for Rubber Research Institute, CATAS (No. 1630022018012; No. 1630022017007).

The online version is available at http://www.springerlink.com

Corresponding editor: Tao Xu.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Y., Jing, Y., Bei, M. et al. Short-term effects of organic amendments on soil fertility and root growth of rubber trees on Hainan Island, China. J. For. Res. 31, 2137–2144 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-019-01023-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-019-01023-7