Abstract

There is a strong driving force to improve the production efficiency of thermal barrier coatings (TBCs) manufactured via air plasma spray (APS). To address this need, the high-enthalpy APS torch Axial III Plus was employed to successfully manufacture TBCs by spraying a commercial YSZ feedstock at powder feed rate of 100 g/min using an optimized set of N2/H2 spray parameters; which yielded an impressive YSZ deposition efficiency (DE) value of 70%. This exact same set of optimized spray parameters was used to manufacture the same identical YSZ TBC (over ~160 µm-thick bond-coated substrates) but at two distinct YSZ thickness levels: (i) ~420 µm-thick and (ii) ~930 µm-thick. In spite of the high YSZ feed rate and DE levels, the YSZ TBC revealed a ~14% porous (conventional looking) microstructure, without segmented cracking or horizontal delamination at both thickness levels. The bond strength values measured via the ASTM C633 standard for the ~420 µm-thick and ~930 µm-thick YSZ TBCs were ~13.0 and ~11.6 MPa (respectively); which are among at the upper end values reported in the literature. After the first objective was attained, the second key objective of this work was to evaluate the thermal insulating effectiveness of these two as-sprayed YSZ TBCs. To achieve this objective, a thermal gradient laser-rig was employed to generate a temperature reduction (ΔT) along the TBC-coated coupons under different laser power levels. These distinct laser power levels generated YSZ TBC surface temperatures varying for 1100 to 1500 °C, for the ~420 µm-thick YSZ TBC, and from 1100 to 1680 °C YSZ TBC ~930 µm-thick YSZ TBC. The respective ΔT values for both TBCs are reported. The results of this engineering paper are promising regarding the possibility of improving considerably the manufacturing efficiency of industrial quality conventional-looking porous YSZ TBCs, by using a high-enthalpy N2-based APS torch. This is the first paper published in the open literature showing R&D results of coatings manufactured via the Axial III Plus APS torch.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs) Manufactured Via Air Plasma Spray (APS)

TBCs manufactured via APS provide thermal insulation from the hot combustion gas stream to the static metallic parts located in the hot sections of gas turbine engines (e.g., combustion chambers, nozzles and afterburners). A thermally sprayed TBC system typically exhibits a bi-layered structure, which includes a ceramic top coat and a metallic MCrAlY (M = Ni, Co, NiCo or CoNi) bond coat (BC). The ceramic top coat (e.g., ZrO2-7-8wt.%Y2O3, a.k.a., YSZ) provides thermal insulation and reduces the heat flow to the turbine metallic part; which is made of a Ni-based high temperature superalloy (e.g., Hastelloy X). The metallic MCrAlY BC is an oxidation/corrosion-resistant metallic layer. It protects the underlying component and improves the adhesion of the ceramic top coat on the part. More detailed information about TBC manufacturing, properties and characteristics can be found in the work of Feuerstein et al. (Ref 1).

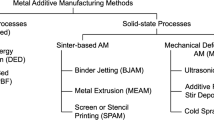

TBC Manufacturing Efficiency

Two critical aspects to be faced by the industry in the twenty-first century are the environment and sustainability. There is a huge driving force to avoid the depletion of natural resources in order to maintain an ecological balance. Reducing environmental footprint means reducing at the same time the amount of natural resources and energy used to produce a product. This need is now demanded in all sectors of the society, which includes the TBC market; more specifically the TBC manufacturing via thermal spray. According to Sampath et al. (Ref 2), in 2011 approximately 1-1.5 million kg of YSZ powders were sprayed onto turbine engine components via APS. It is important to point out that the huge majority of APS torches being employed in the world today are the so-called “legacy” types (e.g., 3MB, 9MB, F4 and variations of these); which use (i) Ar/H2 as standard plasma gases, (ii) exhibit maximum power levels in the range of 40-80 kW and (iii) are usually limited to spray YSZ at maximum powder feed rates of 60 g/min. By understanding the key characteristics of these torches, one can foresee that the loss of the YSZ material is immense. One of the fundamental reasons is the low deposition efficiency (DE) values for YSZ when sprayed via these types of “legacy” equipment and using an Ar/H2 plasma.

Marple et al. (Ref 3) compared the DE values of a YSZ powder when sprayed via a legacy 9MB torch using the standard Ar/H2 versus the alternative N2/H2 plasma. Briefly, the YSZ DE values for the Ar/H2 and N2/H2 plasmas were found to be in the range of 10-38% and 5-70%; respectively. Other studies showed the same trend when legacy APS torches like the 3MB (Ref 4) and 9MB (Ref 5) were employed to spray YSZ. The YSZ DE values for Ar/H2 plasmas were in the range of 30-43%; whereas, those for N2/H2 plasmas were improved and reached 53-62% (without causing a drop in TBC performance with respect to thermal conductivity or thermal cycling).

Therefore, as the majority of the legacy APS torches operating today are using Ar/H2 plasmas to spray YSZ, it can be speculated that of the 1-1.5 million kg of YSZ powder material sprayed per year (Sampath et al. (Ref 2)), only about 40% will in fact become deposited on the turbine components. Consequently, over 50% of the YSZ powder material sprayed will be wasted in dust collectors. This is a serious issue.

The key reasons why Ar/H2 plasmas yield lower DE values than those of N2/H2 ones can be understood by reading the work of Belashchenko and Zagorski (Ref 6). Chiefly, at the same range of plasma temperature conditions (e.g., from 10,000 to 12,000 °C), N2-based plasmas exhibit higher enthalpy (i.e., heat content) levels than those of Ar-based ones. By giving one specific example, at 12,000 °C, the enthalpy (kJ/liter) of the N2 plasma is ~4X higher that of the Ar plasma. In addition, Murphy and Arundell (Ref 7) showed that for this same temperature plasma temperature range (i.e., 10,000-12,000 °C), the thermal conductivity of N2 plasma varies from ~1.5 to 2.0 W/mK, whereas that of the Ar plasma ranges from ~0.5 to 1.5 W/mK. More specifically, at 12,000 °C, the thermal conductivity of the N2 plasma is ~30% higher than that of the Ar plasma. Consequently, the higher heat content and thermal conductivity values of N2-based plasmas (when compared to those of Ar-based) yield these known higher DE values during YSZ TBC manufacturing. As a side note, it needs to be mentioned that H2 is typically employed as a secondary gas for either Ar or N2 primary gas plasmas. The H2 gas increases even further the thermal conductivity (i.e., thermal efficiency) of the Ar and N2 primary plasmas. However, it does not significantly affect the fundamental heat content of the gas mixture (Ar/H2 or N2/H2), as described by Belashchenko and Zagorski (Ref 6).

In spite of the obvious advantages, N2-based plasmas typically have a “bad reputation” in the thermal spray community. The main reason is based on the fact that for these legacy torches, it tends to wear the torch copper (Cu) nozzle (anode) at rates quicker than that of the Ar plasma. This accelerated erosion will lead to an earlier variation and destabilization of the plasma plume conditions, thereby leading to TBC manufacturing reliability problems. El-Zein et al. (Ref 8) have shown that under similar gas flow levels, the current density (A/cm2) of a N2 plasma is ~25% more intense than that of an Ar one. This superior current density is linked to an enhanced heat load of the nozzle wall and thus its accelerated erosion. Consequently, Ar is generally chosen as the standard primary plasma gas (mainly for the legacy APS torches), in spite of (i) the typically low YSZ DE values (<50%) yielded by this gas and (ii) the usual maximum limitation of YSZ powder feed rate of 60 g/min for Ar/H2 legacy APS torches. However, this tendency for accelerated Cu nozzle erosion for N2-based plasmas can be counter-acted by employing tungsten-lined nozzles. On the other hand, even by using a N2-based plasma, these legacy torches are still limited to work at maximum power levels in the order to 40-80 kW.

As another alternative that can be explored are more modern high-enthalpy APS torches. These torches are able to handle well power levels of approximately 100 kW (or even superior values) and are typically designed from the get-go to operate with N2-based plasmas. The combination of elevated plasma power levels (~100 kW) with the N2 high enthalpy plasma gas has the potential improve significantly the manufacturing of YSZ TBCs, by concomitantly (i) enhancing YSZ DE levels to >50% (i.e., reducing waste), (ii) allowing YSZ powder feed rates of 100 g/min (or higher), thereby (iii) reducing the time needed to have a component coated. In addition to providing improved DEs, the cost per m3 of the N2 gas is ~25% lower than that of the Ar (at same purity levels); which improves even further the manufacturing efficiency. Finally, concerns about the use of a N2-based plasmas can also be addressed by the use of computer-controlled consoles, mass-flow controllers, sensors, digital twin, big data and artificial intelligence (i.e., Industry 4.0 concepts). In this way, underdeveloped manufacturing issues can be detected and corrected before they become significant. There is an important future and a bright road of R and D activities in this area.

Understanding Thermal Gradients within TBCs and Metallic Components

TBCs reduce the temperature of the metallic components located in the hot section of gas turbine engines. These components, made from Ni-based superalloys (melting point ~1300-1400 °C), typically exhibit a wall thicknesses in the range of only ~1–2 mm. Moreover, they are subjected to elevated temperatures resulting from the hot stream of the combustion gases, which can reach a maximum peak of 2000 °C inside the combustion chamber. For this reason, the thermal insulation of the metallic turbine component is the “raison d'etre” of the TBC.

In spite of this fundamental importance, little information is available on the real thermal gradients generated across the overall thickness of TBC/metallic-component architectures (at least in the open literature). This type of information is paramount for engineers, researchers and students working in this field. They have to find the “optimal compromise” in keeping the YSZ TBC surface temperature below an upper temperature limit and at the same time keeping the MCrAlY BC and metallic Ni-based superalloy turbine component below another upper temperature limit.

For current state-of-the-art TBCs, the YSZ TBC surface temperature (T-ysz) shall not exceed ~1300 °C at the same time not allowing the MCrAlY BC (T-bc) and substrate component (T-sub) temperatures to reach values above ~1100 °C and ~1000 °C; respectively. The upper surface temperature limit for YSZ TBC of ~1300 °C was established based on distinct YSZ degradations. They become exacerbated at temperatures higher than ~1300 °C and are caused by:

-

(i)

YSZ delamination led by calcia-magnesia-alumina-silica (CMAS) glass deposits; as per Borom et al. (Ref 9)

-

(ii)

YSZ phase transformations; as per Brandon and Taylor (Ref 10)

-

(iii)

YSZ sintering; as per Thompson and Clyne (Ref 11)

The upper temperature limit of the MCrAlY BC of ~1100 °C is based on the thickening of the Al2O3-based thermal grown oxide (TGO) layer (formed at the YSZ TBC/BC interface), which is caused by the oxidation of the BC and is proportional to the operational temperatures. After a critical TGO layer thickness is reached, the stresses lead to the crack, failure and spallation of the YSZ TBC (which occurs at and/or alongside the TGO layer). As shown by Vaßen et al (Ref 12), when the APS YSZ TBCs are burner-rig cycled within a range of 1030-1100 °C for BC (i.e., T-bc), the thermal cycle lifetime of an APS TBC is drastically reduced when T-bc approaches 1100 °C.

The upper temperature limit for the Ni-based superalloy substrate components (T-sub) is typically considered to be ~1000 °C and it is related to yield strength. The yield strength indicates the limit of elastic behavior and the beginning of plastic behavior of materials. Data on the yield strength values in function of temperature for different Ni-based polycrystalline superalloys employed in the hot-sections of gas turbine engines can be found in the literature (Ref 13). The yield strength values of these alloys at a T-sub of ~1000 °C are rapidly approaching their respective plastic deformation zones.

A previous study spotlighted the thermal gradients obtained across a thermally sprayed APS YSZ TBC/substrate architecture (Ref 14). A thermal gradient laser-rig was used to create the temperature drop between the YSZ TBC and the substrate. A CO2 laser heated the YSZ TBC surface, while an air jet was cooling the uncoated back-side of the substrate. By using this instrument, the thermal gradients can be created, evaluated and measured. In addition, this study also provided a summary of different thermal gradient values reported in the literature (based on burner-rig and laser-rig data) for APS YSZ TBCs.

It needs to be stressed that this temperature compromise mentioned above is also dependent on the TBC thickness and its thermal conductivity (TC) levels. Helminiak et al. (Ref 15) explored the concept of thermal resistance (Rtherm) for TBC systems; which is given by:

where “thick” is the thickness and “TC” is the thermal conductivity of the ceramic top coat. The thermal resistance is a measure of the thermal insulating effectiveness of a TBC. It can be maximized by increasing the thickness of the ceramic top coat and/or by minimizing the thermal conductivity of the ceramic top coat. Evidently, the target is defined by trying to get the best compromise between the BC and substrate temperature and the TBC surface temperature. Since the heat intensities and cooling efficiencies of a turbine vary across the different component locations, this “optimal” compromise can be achieved by spraying the same YSZ TBC but manufactured at different thicknesses accordingly to the temperature reduction needs.

Objectives

This engineering paper has two major objectives that are (i) addressing TBC manufacturing efficiency issues and (ii) providing additional data on the thermal gradients within TBCs and metallic components. By addressing TBC manufacturing efficiency, the target was to deposit a conventional looking (porous) YSZ TBC using a high-enthalpy 150 kW APS torch (N2-based plasma), at a powder feed rate of 100 g/min and at the same time reaching a YSZ DE value of at least 60%. Besides, this YSZ TBC needs to be porous of “conventional looking industrial quality”. In other words, it needs to exhibit porosity levels within those typically accepted for porous TBCs of aerospace turbines (i.e., 10-20%) and bond strength levels found within those reported in the literature for APS YSZ TBCs.

Regarding providing additional data on TBC thermal gradients, the same YSZ TBC described above was sprayed at two distinct sets of thickness: 400-500 µm and 900-1000 µm. By employing a thermal gradient laser-rig, different thermal gradients were produced and reported in this manuscript. The aim was to determine the maximum temperature a porous YSZ APS TBC can be subjected while maintaining the temperature of the substrate temperature at values no higher than ~1000 °C. It is believed that these sets of results are of high importance to TBC designers, mainly regarding modelling and simulation.

Experimental Procedure

TBC Manufacturing

All TBCs produced for this study (including top and bond coats) were sprayed using the same high-enthalpy 150 kW APS torch (Axial III Plus, Northwest Mettech, Surrey, BC, Canada). The Axial III Plus is a smaller (length 15.5 cm and width 8.6 cm) and 90° version of the original Axial III torch. In fact, it is ~50% shorter and ~5% narrower than the original Axial III. Although smaller, it can use the same console, chiller, power supply, spray parameters and power levels of those of the original Axial III torch. The schematics of original Axial III and Axial III Plus torches side by side can be seen in Fig. 1(a). Due to its 90° configuration, the Axial III Plus can be potentially applied to spray coatings in internal diameters (IDs). In this study, the spray distance (SD) employed to spray both the MCrAlY BC and the YSZ top coat was 7.5 cm. For this reason, based on the (i) torch length of 15.5 cm, (ii) SD of 7.5 cm and (iii) assuming the need of having 2 cm safety gap; it can be presupposed that this TBC could be sprayed inside a minimum ID of 25 cm (10”). However, in this work the coatings were sprayed in outer diameter (OD) configuration.

For microstructural characterization and bond strength testing, the TBCs were manufactured on puck-shaped (25.4 mm diameter and 6.4 mm thick) low carbon steel substrates. The substrates were grit-blasted with white Al2O3 grit #60 at 4.1 bar (60 psi) prior to BC spraying. The low carbon steel substrate roughness (Ra) value (stylus profilometer) after grit-blasting was 3.2 ± 0.2 µm (n = 10 at a cut-off length (λc) of 2.5 mm)

For thermal gradient laser-rig testing, the TBCs were manufactured on puck-shaped (25.4 mm diameter and 3.2 mm thick) Rene’ N515 substrates. Before spraying, a 0.87-mm hole was drilled at the mid-thickness of the substrate throughout its entire 25.4 mm diameter (for thermocouple insertion during thermal gradient testing). In addition, on the side where the TBCs were deposited, the edges were rounded up to minimize sharp-corner stresses that arise during coating deposition and thermal gradient testing. The substrates were grit-blasted with white Al2O3 grit #24 at 2.8 bar (40 psi) prior to BC spraying. The Rene’ N515 substrate roughness (Ra) value (stylus profilometer) after grit-blasting was 5.0 ± 0.3 µm (n = 10 @λc = 2.5 mm). In order to improve the uniformity of the study, the spraying of the BC and YSZ top coat occurred at the respective same runs for both types of substrates.

The BC feedstock composition was the NiCoCrAlY-HfSi (Amdry 386-4, Oerlikon Metco, Westbury, NY, USA). This powder displays a particle size distribution of d10: 48 μm; d50: 59 μm; d90: 75 μm. The BC was sprayed using an Ar/N2/H2 plasma composition at a SD of 7.5 cm using a carrousel fixture (sample tangential speed of 1.2 m/s and torch transverse speed of 5 mm/s). The BC thickness was ~160 µm. The BC roughness (Ra) value (stylus profilometer) was 13.31 ± 1.26 µm (n=10 @λc = 2.5 mm).

The top coat YSZ feedstock was ZrO2-8wt.%Y2O3 (204B-NS, Oerlikon Metco, Westbury, NY, USA). The powder displays a particle size distribution of d10: 37 µm, d50: 62 µm and d90: 84 µm. The YSZ was sprayed using an N2/H2 (75vol%/25vol% @98 kW of power) plasma composition at a SD of 7.5 cm using a carrousel fixture (sample tangential speed of 2.4 m/s and torch transverse speed of 10 mm/s). The exact same set of optimized spray parameters were used to deposit two YSZ TBCs of different thicknesses values: (i) ~420 µm and (ii) ~930 µm. The roughness (Ra) values (stylus profilometer) for the ~420 µm-thick and ~930 µm-thick YSZ TBCs were 12.55 ± 1.17 µm and 12.39 ± 0.95 µm (n=10 @λc = 2.5 mm); respectively.

The YSZ deposition efficiency (DE) values were calculated by spraying YSZ onto grit-blasted Almen N strips (76.2 mm x 19.05 mm x 0.79 mm) without BC. The Almen N strips were placed together in the carrousel fixture along the other samples produced for this study. The DE was measured based on the weight of the strips before and after YSZ deposition, as well as, on the powder feed rate and on the total time the torch was over the strip during spraying.

During spraying, a vortex air jet fixture cooling and two overspray air jets mounted on the torch were employed together to limit the temperature of the samples during coating manufacturing. The coating surface temperature during spraying was monitored via an infra-red (IR) camera (FLIR A320), mounted in line-of-sight of the carrousel-held sample at 90° angle from the plasma spray jet. Consequently, during deposition the torch never blocked the sight of the camera. The complete sets of spray parameters for this TBC architecture are considered as intellectual property (IP) of the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) and cannot be divulged. However, an overall summary of the spray parameters, including plasma gas combination, powder feed rate, plasma torch power, deposition rate (DR), deposition efficiency (DE) values can be found in Table 1.

YSZ TBC Density and Porosity Values

The density value of the as-sprayed YSZ TBC (dysz) was measured via the Archimedes technique in water: dysz (g/cm3) = (dwater x mdry) ÷ (mwet - mimmersed); where dwater is 1.00 g/cm3 and m is the YSZ free-stand mass in grams. A total of 3 free-standing YSZ coatings were used to determine the density values. A ~930 µm-thick YSZ TBC (deposited together with tested samples) was deposited on grit-blasted puck-shaped (25.4 mm diameter and 6.4 mm thick) low carbon steel substrates without BC. Subsequently free-standing YSZ coatings were obtained by placing the coupons in an acid bath (45vol% HNO3 + 45vol%H2SO4 + 10 vol.% H2O), which dissolved the metallic substrate. After substrate dissolution, the YSZ free-stands were washed in water and dried in a lab stove at 125 °C for 2h.

The as-sprayed YSZ porosity value was estimated based on the ratio between the coating density (measured via Archimedes) with that of a fully dense bulk YSZ sample; i.e., 6.00 g/cm3. Exemplifying, if a free-stand YSZ TBC density is 5.17 g/cm3, and is then divided by the bulk density of the YSZ (6.00 g/cm3) and multiplied by 100; this gives a value of 86.2. Consequently, the YSZ TBC density is 86.2% that of the fully dense bulk. Thereby, porosity value of the YSZ TBC is 13.8%.

Cross-sectional Microstructural Characterization

In order to better preserve their real microstructures, the as-sprayed TBC samples were initially vacuum impregnated in epoxy resin and posteriorly ground/polished according to standard metallography procedures for TBCs. The cross-sectional microstructural features of the TBCs were analyzed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). In addition, the elemental composition of the MCrAlY BC was evaluated via energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDX).

X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

XRD using CuKα radiation was employed to evaluate the phase compositions of the as-sprayed YSZ TBCs. The XRD 2θ values ranged from 20° to 80° (scanning step size of 0.05° and step time of 2.5 s).

Bond Strength

The as-sprayed bond strength of the two TBCs produced in this study were measured using the ASTM C633 standard (Ref 16). In ASTM C633 standard, the coating and respective substrate (25.4 mm diameter) are bonded to loading fixtures using an epoxy glue; the full assembly is then subjected to a tensile load that is perpendicular to the plane of the coating. The epoxy glue FM1000 (Couch Sales LLC, Hilton Head Island, SC, USA) was used (it requires 1.5 h at 180 °C for curing) to assemble the testing set-up. The FM1000 glue was chosen in order to prevent impregnation of the ceramic coating and influence on the adhesion result. An Instron 5582 universal testing machine (Burlington, ON, Canada) was used with a dynamic load up to 100 kN at a constant speed of 1.2 mm/min. A reference dummy sample used to verify the glue performance; which yielded a strength value of 77 MPa.

YSZ Elastic Modulus Via Instrumented Indentation Testing

Instrumented indention testing (G200, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was employed to measure the elastic modulus values of the as-sprayed YSZ TBCs. This technique was developed by Oliver and Pharr (Ref 17), where the mechanical properties of materials can be determined directly from the indentation load and indentation displacement using high-resolution testing equipment. The system employed a Berkovich indenter and was performed by using these main equipment set-up inputs: YSZ Poisson’s ratio estimated at 0.25, time to load 15 s, maximum indentation load of 50 gf and hold time at maximum indentation load of 10 s.

The elastic modulus values were measured over the polished cross sections of the coatings prepared for SEM evaluation (as described above). For each YSZ TBC, a total of 3 series zones were tested: (i) next to BC (~50 µm from BC), (ii) mid-coating thickness and (iii) next to outer surface (~50 µm from epoxy resin). A total of 25 indentations were taken for each single zone; i.e., each YSZ TBC was indented 75 times.

Before testing the samples, the calibration of the equipment was double-checked with a fused silica (SiO2) standard, using the same indentation set-up inputs. A total of 5 indentations were generated before the TBCs were probed. An average elastic modulus value of 71.8 ± 0.3 GPa was obtained, which is close to the results reported by Oliver and Pharr for SiO2, i.e., ~70 GPa (Ref 17).

Thermal Gradient Laser-Rig Testing

The main characteristics of NRC’s thermal gradient laser-rig has been previously described elsewhere (Ref 14). It is based on a 3-kW CO2 laser, which produces a constant laser beam (10.6 µm wavelength) over the YSZ TBC top coat. The rig is set to create a laser spot size of about 25 mm (1”) in diameter, in order to fit the dimensions of the puck-shaped coupon. A compressed air jet at room temperature (RT) cools the un-coated backside of the substrate in order to generate the thermal gradient across the TBC/substrate profile. The rig is closed-loop computer-controlled; therefore, the temperature of the YSZ top coat (T-ysz) and the temperature of the substrate (T-sub) are continuously monitored during the tests. The overall image of the laser-rig is found in Fig. 1(b).

The temperature of the YSZ top coat (T-ysz) was monitored using a one-color 7.9-µm wavelength pyrometer with a spot size of ~7 mm at the center of the sample. An infrared (IR) camera (7.5-14 µm spectral range) coupled with a CO2 notch filter at 8 µm was also employed to measure the overall distribution of temperature on the surface of the YSZ top coat. The IR camera is used as a guide to guarantee that a uniform laser beam is right centered on surface of the TBC. The emissivity value for the YSZ was measured and set as 0.96 for a IR wavelength of 7.9 µm; which is similar to the 0.94 value reported by González-Fernández et al. (Ref 18) for YSZ at this wavelength.

The substrate temperature (T-sub) was measured at the coupon center by using a thermocouple (Omega, KMQIN-032U-12, Nicrosil/Nisil, Norwalk, CT, USA) that was inserted into a hole drilled at the mid-thickness position of the 25.4 mm diameter puck-shaped substrate (Fig. 1b). For this reason, as the substrate is 3.2 mm-thick, the T-sub was measured at a position of ~1.6 mm beneath the BC/substrate interface.

For creating the temperature profiles (ΔTs) via the laser-rig along the thicknesses of the TBC/substrate systems, initially the RT cooling air jet on the un-coated backside of the substrate was set to be constant at ~430 lpm. Therefore, the cooling conditions were identical to all TBC-coated samples during this study. For this reason, to generate the distinct ΔTs, the laser power was adjusted and set to keep the YSZ TBC surface temperature (T-ysz) constant at pre-set values, e.g., 1100, 1200, 1300 °C (i.e., 100 °C steps) and so on. Thus, the higher the T-ysz pre-set, the higher the laser power necessary to achieve the T-ysz pre-set value. The T-ysz was increased until the temperature of the substrate (T-sub) reached around 1000 °C; which is typically considered to be the highest limit of temperature operation for static gas turbine components (e.g., combustion chamber).

The same as-sprayed sample of each YSZ TBC system produced in this work (~420 µm-thick and ~930 µm-thick) was used in these experiments establish the thermal gradient and measure the ΔTs. Each single set of ΔTs were generated for nearly 30 min. This amount of time was chosen as to be a compromise between (i) having a “long enough” stable period to measure the ΔT of an as-sprayed TBC and (ii) but at the same time not having a “long enough” high temperature exposure to minimize TBC sintering effects.

Results and Discussion

APS NiCoCrAlY+HfSi Bond Coat

Figure 2 shows the SEM cross-sectional micrograph of the NiCoCrAlY+HfSi BC sprayed via the Axial III Plus (without the YSZ TBC). The maximum BC surface temperature reached during spraying was ~550 °C (monitored using an infra-red camera). The chemical composition of the BC was determined via EDX within the rectangular area (~500 µm x ~55 µm) featured over the BC and the results shown in Table 2. It is possible to observe that the chemical composition of the as-sprayed BC is found within the range of that of the MCrAlY powder feedstock (provided by the powder manufacturer). The amount oxygen in the as-sprayed BC is ~1.4 wt.%. This amount is within the range of those exhibited by NiCoCrAlY+HfSi BCs when deposited via APS at the NRC (i.e., ~0.7-1.5wt.%) and when measured by the same technique.

As-sprayed cross-sectional SEM picture of the NiCoCrAlY+HfSi BC employed in this study - the rectangular box identifies the area where EDX mapping was performed (Table 2)

The BC Ra value was 13.31 ± 1.26 µm (n = 10 @λc = 2.5 mm). According to Feuerstein et al. (Ref 1), in order to provide optimum adherence for a ceramic TBC, a surface roughness (Ra) of the MCrAlY BC of at least approximately 10 µm is desirable so as to mechanically anchor the layers together. Typical Ra values of thermally sprayed MCrAlY BCs are within the ranges 7-10 µm as reported by Schmidt et al. (Ref 19) and by Eriksson et al. (Ref 20), as well as, 10-13 µm as reported by Haynes et al. (Ref 21). Consequently, the Ra value reported for the BC produced in this work is located in the upper range of the values reported in the literature and above the minimum Ra value recommended by Feuerstein et al. (Ref 1).

Schmidt et al (Ref 19), Eriksson et al. (Ref 20) and Bossmann et al. (Ref 22) demonstrated that the higher BC roughness values lead to a longer lifetime performance of YSZ APS TBCs when subjected to thermal cycling. Although the YSZ TBC cracking, failure and spallation occurs at the TGO region and a critical TGO thickness is needed for the spallation of the YSZ TBC, the critical value of TGO thickness depends on the roughness value of the BC (i.e.; the rougher the BC, the thicker the TGO critical thickness). Understanding the mechanisms of failure of TBCs is a complex issue. Besides characteristics like BC surface roughness and TGO layer thickening; factors like BC composition, BC spraying (e.g., BC as-sprayed oxidation), operating temperature, cycles, mechanical loading, stresses, phase transformations and atomic diffusion play important roles in the outcome. Nonetheless, in a “very simplistic way”, it is known that the crack path that leads to the YSZ TBC spallation originates and propagates at and/or alongside the TGO layer (which forms over the BC roughness). For this reason (for the same BC composition and deposition method) usually the rougher the surface of the BC, the longer the critical path for crack propagation to promote YSZ TBC spallation. As a consequence, typically rougher BC surfaces tend to translate into longer thermal cycle lives for APS YZ TBCs. Therefore, the high Ra value of ~13 µm reported for the BC manufactured in this work can be preliminary considered as “a desirable target”; but further thermal cycle testing is necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

By looking at Table 1, one can notice that the BC powder was sprayed at 50 g/min of powder feed rate and its DE value was 55% when sprayed at 71 kW. It is difficult to find information on the open literature about the DEs of MCrAlY BCs deposited via APS. However, based on NRC’s own experience, the combination of the powder feed rate employed (50 g/min) and resulting DE (55%) is considered to be “good” for a BC manufactured via APS. Of course, this DE value could be easily augmented by further increasing the plasma torch power (for example). On the other hand, the BC can become highly oxidized. The production of BCs via APS needs to find the “right balance” of obtaining at least “acceptable” values of powder feed rate, DE, as-sprayed BC Ra and oxidation levels.

APS YSZ TBC Architectures: Microstructure

As described in Table 1, the YSZ power feed rate and its DE value were 100 g/min and 70%, respectively. These can be considered “very high values” and show the effectiveness of a N2-based high-enthalpy APS torch to spray large amounts of YSZ and still obtaining an impressive DE level. It is important to point out that the majority of the porous APS YSZ TBC manufacturing being done today is performed by “legacy” torches, employing Ar-H2 plasmas, where the YSZ powder is typically sprayed at 60 g/min or lower and the DE values are about 40% or below.

Nonetheless, it needs to be stated that superior DE levels and powder feed rates do not necessarily yield desired results. In fact, it is the contrary; they will tend to increase even further the stresses that occur during thermal spray deposition, which can lead to unwanted segmentation cracking, inter-pass delamination and reduced bond strength. For this reason, observing the microstructures is of paramount importance.

Figure 3 shows the SEM cross-sectional micrograph of the two full architecture TBCs manufactured via the Axial III Plus for this work: (i) ~420 µm-thick YSZ TBC (Fig. 3a) and (ii) ~930 µm-thick YSZ TBC (Fig. 3b). It is important to remember that both YSZ TBCs (i) were deposited on the same ~160 µm-thick BC and (ii) sprayed using the same set of spray parameters (as per Table 1), i.e., only the YSZ thickness changes. At the YSZ DR of ~23 µm/pass, a total of 18 and 40 torch passes were employed to deposit the ~420 µm-thick and ~930 µm-thick YSZ TBCs; respectively. The maximum YSZ surface temperature (monitored using an infra-red camera) initially started to increase with each single torch pass (as expected); but stabilized at ~600 °C after about 8-9 torch passes for both YSZ top coats. Consequently, a sample temperature stabilization was reached during spraying. This sample temperature stabilization most likely influenced the mechanical properties of TBCs, such as bond strength and elastic modulus values (to be discussed in the next paragraphs).

By looking at Fig. 3, it is possible to observe that both YSZ TBCs exhibit a conventional porous microstructure. It is noticed the presence of interlamellar boundaries, globular voids and microcracks; which are the result from previously molten and semi-molten YSZ particles that flattened, overlapped and re-solidified into an assembly of lamellas during spraying. There are no major cracking segmentation, horizontal inter-layer delamination or adhesion gaps at the YSZ/BC interface. This is an important result. It shows that under controlled conditions of spraying (e.g., spray parameters, torch/substrate relative motion and maximum coating temperature during spraying), superior yield TBC manufacturing can be performed without producing unwanted defects into the TBC microstructure. The as-sprayed density and porosity values of the YSZ TBC are ~5.15 g/cm3 and ~14%, respectively (Table 3). Therefore, this APS YSZ TBC has a porosity level in the range of 10-20%, which is accepted for a porous TBC.

As a final remark, it needs to be stressed that APS YSZ TBCs exhibiting thickness around 1000 µm (just like the one of this work) or even thicker are nothing new. They have been successfully applied in the industry, mainly for industrial gas turbines (IGTs) for many years. What this work wants to bring attention is the fact that these conventional porous TBCs can be manufactured not only at high powder feed rates, but also at high DE levels.

APS YSZ TBC Architectures: As-Sprayed Bond Strength

Bond strength testing is a very important complement feature to the microstructural characterization described in the previous session. As discussed, both YSZ top coats exhibited conventional porous microstructures and no major defects (Fig. 3). They were sprayed at 100 g/min and the DE value is 70%. These are coveted very high values. However, they may cause an over increase of residual stress levels, which could lead to low TBC adhesion values (mainly for the thicker ~930 µm-YSZ TBC) and perhaps a “weak” performance during thermal cycling.

As an example, Vaßen et al. (Ref 23) produced YSZ TBCs via APS under different YSZ powder feed rates: 4.4, 9.1, 36.4 and 54.7 g/min. All TBCs were porous (12-15%) and subjected to burner-rig testing under similar thermal gradient conditions. There was an increase of ~20% in the number of cycles to failure for the TBCs produced from 4.4 to 9.1 g/min; which was the best performing. On the other hand, from 9.1 to 54.7 g/min, there was a reduction of ~86% in the number of cycles to failure; which is considerably negative. Therefore, one may claim that elevated powder feed rates over 50 g/min are inherently negative. However, the YSZ deposited at 9.1 g/min (best performing) exhibited a DR of ~7 µm/pass; whereas that of the 54.7 g/min YSZ (worst performing) was ~31 µm/pass; i.e., 4.4X higher. Consequently, it can be hypothesized that the enhanced powder feed rate was not necessarily the main responsible for the outcome, but rather the thicker DR (i.e., increased residual stress effects). For this reason, when spraying YSZ at powder feed rates of ≥50 g/min, it is important to adjust the relative speed of the substrate surface and torch in order to avoid maximizing DR levels.

Thus, although the TBCs manufactured in this work do not exhibit unwanted defects (Fig. 3), to double-check if they were not “weakened” by residual stress effects, measuring their bond strength values is key to validate the microstructural results. The as-sprayed bond strength (ASTM C633) results and complementary data of both TBC manufactured for this study are found in Table 3. Briefly, the bond strength for the ~420 µm-thick TBC is ~13.0 MPa, whereas that of the ~930 µm-thick TBC is ~11.6 MPa. This is considered as an interesting result. Despite the fact that one YSZ TBC is twice thicker than the other, the drop of bond strength intensity for the thicker ~930 µm YSZ TBC is just 11%.

To better understand this small drop of TBC bonding, it is important to look at the data of Table 1. Initially, one needs to remember that both YSZs were sprayed over the same APS BC. As previously described, the maximum coating surface temperature during spraying grew in time with each single torch pass; however, it stabilized at ~600 °C for both YSZ top coats after approximately 8-9 torch passes. In addition, the DR values were the nearly identical (~23 µm/pass) for both YSZ TBCs. The only major difference during spraying was the additional the number of torch passes required to spray the thicker YSZ TBC; i.e., 18 (~420 µm-thick YSZ) versus 40 torch (~930 µm-thick YSZ) passes.

To complement the discussion, the snap-shots of the fracture surfaces of tested samples are shown in Fig. 4 and also help to understand this issue. First of all, it is possible to notice that for both TBCs the BC remained adhered to the substrate. In addition, all TBC samples exhibited mixed bond strength failure, i.e., a combination of adhesive (YSZ/BC interface) and cohesive (within YSZ) failures. However, for the ~420 µm-thick TBC, the failure was more adhesive; i.e., concentrated at the YSZ/BC interface. This conclusion is obtained by seeing the fracture surfaces on the substrate side (Fig 4a). The area amount of BC exposed (grey zone—YSZ/BC adhesive failure) is larger than that of the YSZ (white zone – YSZ cohesive failure). For the ~930 µm-thick TBC, the amount of white area (YSZ cohesive failure) on the substrate side (Fig. 4b) becomes more evident, but the overall mixed failure characteristic is still similar to that of Fig. 4(a). For this reason, the small variation of macrostructural features of the fracture surfaces between both TBCs also help to understand the small drop of bond strength of the thicker coating.

The elastic modulus values of both YSZ TBCs measured via instrumented indentation can also shine a light on this subject. As described in "Thermal gradient laser-rig testing" section, for each YSZ TBC, a total of 3 series zones were tested: (i) next to BC (~50 µm from BC), (ii) mid-coating thickness and (iii) next to outer surface (~50 µm from epoxy resin). A total of 25 indentations were taken for each single zone; i.e., each YSZ TBC was indented 75 times. These elastic modulus measurements can be found in Fig. 5. Essentially, the average and standard deviation values for both coatings, measured at the same equivalent zones, do not show a significant variation. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) confirmed that for each individual YSZ TBC, at the 0.01 level (i.e., 99%), the population means are not significantly different (for each indentation zone). In simple words, it is not observed a noticeable gradient or variation of elastic modulus values for both coatings and they are relatively uniform across the coating thickness, not mattering if the YSZ TBC thickness is ~420 or ~930 µm. As previously stated, the DR values were the nearly identical (~23 µm/pass) for both YSZ TBCs. In addition, the maximum coating surface temperature during deposition increased in time with each single torch pass; however, it never went above ~600 °C for both YSZ top coats during spraying after 8-9 passes. Consequently, temperature distribution of the samples plateaued and stabilized during processing. Most likely these elements contributed to the uniformity elastic modulus results shown in Fig. 5; which in turn also help to explain (i) the low difference of bond strength between both TBCs (Table 3), (ii) their same failure mode (iii) and similar fracture surfaces (Fig. 4).

It is important to stress that Shinde et al. (Ref 24) also observed a similar behavior. It was reported the progression of the elastic modulus values (in-situ beam curvature method) along the thickness for a conventional porous APS YSZ TBC. Just like what was observed in this work, the maximum surface temperature of the TBC started to increase with the number of torch passes, but it stabilized at ~550 °C after the initial 6-7 passes (of a total of 20+ passes). Within a range from approximately 100 to 700 µm, the conventional porous YSZ exhibited nearly constant elastic modulus values over all thicknesses (~50-60 GPa).

Another important point to be considered is the comparison of the bond strength values reported in this manuscript with those reported in the literature for porous and dense-vertically-cracked (DVC) APS YSZ TBCs. In simple words, it is necessary to know if the bond strength results reported in this manuscript are “good”. Table 4 displays literature values for as-sprayed porous and DVC YSZ TBCs, based on the results of Guerreiro et al. (Ref 5), Smith et al. (Ref 25), Curry et al. (Ref 26), Lee et al. (Ref 27) and Myoung et al. (Ref 28). It needs to be stressed that just like in this work, these bond strength values were also determined via the ASTM C633 method. Overall, APS YSZ TBCs are exhibiting bond strength levels ranging from ~3 to ~15 MPa within a wide variation of thicknesses (~400-2000 µm) and porosity (~3-23%) values. However, when the TBCs thicker than ~1000 µm are not considered (independently of porosity content); the bond strength values are found within the ~7-15 MPa range (Table 4). For this reason, it can be stated that the bond strength levels of the TBCs manufactured this study (i.e.; 11.6-13 MPa) are within the upper range of the values of those reported in the literature; which is a “good” result. As an industrial application curiosity, Smith et al. (Ref 25) reported that the lower bond strength acceptance limit for an industrial APS YSZ TBC exhibiting 10-15% porosity would be 7.6 MPa. Therefore, both coatings sprayed in this study would far exceed the minimum bond strength requirements for a TBC in this case.

As this manuscript deals with YSZ spraying at high powder feed rates using a high-enthalpy plasma torch, it is interesting to further mention the works of Curry et al. (Ref 26), Lee et al. (Ref 27) and Myoung et al. (Ref 28); which also dealt with the same subject. Curry et al. (Ref 26) sprayed two YSZ powders at 280 g/min using the high-enthalpy 100HE APS torch (Progressive Surface, Grand Rapids, MI, USA). YSZ DE values ranging from ~40-52% were reported, and the porosity, thickness and bond strength values of these TBCs are found in Table 4. From these sets of data one can realize that YSZ powders can be sprayed at 280 g/min and respective TBCs still exhibiting porosity levels acceptable for IGTs (i.e., 20-30%) and bond strength values within the ~7-15 MPa range can be produced. Nonetheless, this elevated powder feed rate of 280 g/min most likely limited the YSZ DE levels to 52%. The YSZ TBCs of Lee et al. (Ref 27) listed in Table 4 were sprayed at 100 g/min using the legacy torch 9MB (Ar/H2 plasma) and the cascade torch TriplexPro (Ar/He plasma), both from the same company (Oerlikon Metco, Westbury, NY, USA). Unfortunately the YSZ DE values were not reported by the authors. The YSZ TBCs of Myoung et al. (Ref 28), also shown in Table 4, were also sprayed at 100 g/min using the TriplexPro (Ar/He plasma). Here, again the YSZ DE values were not reported.

APS YSZ TBC Architectures: XRD Phase Composition

Figure 6 shows the XRD diffraction patterns of the YSZ powder feedstock and both as-sprayed YSZ TBCs. To analyze the XRD spectra of YSZ, it is generally easier to split the patterns into two zones, i.e., 2θ from ~27.5 to 32.5° (Fig. 6a) and from ~72 to 76° (Fig. 6b). By looking at Fig. 6(a) one wants to know if the presence of the unwanted monoclinic (m) phase of YSZ is observed in the powder and as-sprayed TBCs. The m-YSZ phase is unwanted to due its known stress-induced martensitic transformation. Based on the YSZ phase diagram depicted by Brandon and Taylor (Ref 10), this phase transformation occurs approximately at 100 °C, i.e., very close to RT. Therefore when the TBC is heated from RT to turbine operation temperatures, this m-YSZ phase (if present) transforms into the tetragonal (t) YSZ phase, which accompanied by a volume shrinkage of 3-5%. On the contrary, when the TBC cools down to RT, the t-YSZ phase transforms again into the m-YSZ, which then is followed by a volume expansion of 3-5%. These phase transformations add an additional undesired fatigue stress mode into the TBC system, which helps to lead to early coating spallation. For example, Witz and Bossmann (Ref 29) analyzed the XRD of a delaminated YSZ TBC sample taken from an engine where accelerated TBC degradation was observed. The TBC is composed mostly of m-YSZ (>70 wt.%). For this reason, the presence of m-YSZ phase is extremely undesirable in the TBC phase composition.

The m-YSZ, if present, can be identified by its 100% and 70% highest intensity powder diffraction file (PDF) peaks (PDF #37-1484); which are found at 2θ values of ~28.2° and ~31.5° for the CuKα radiation of the XRD. By looking at the XRD pattern of Fig. 6(a), it is possible to notice a minor presence of the m-YSZ for the feedstock powder and the total absence of it for the two YSZ TBCs. The minor presence of the m-YSZ in the powder is probably related to an incomplete mixture (i.e., alloying) of ZrO2 and Y2O3 during the synthesis of the feedstock. The welcome absence of the m-YSZ phase in both as-sprayed YSZ TBCs is likely to be related to (i) the high degree of melting of the powder during spraying, which improved its alloying and (ii) the fast cooling rates of the molten YSZ splats during re-solidification upon spraying; as described by of Brandon and Taylor (Ref 10).

The other phase to be identified is the so-called non-transformable tetragonal prime (t’) phase of YSZ (PDF #48-0224). The t’-YSZ phase, although metastable, it displays a sluggish phase transformation into the regular tetragonal (t) YSZ (PDF #82-1245) and cubic (c) YSZ (PDF #30-1468) up to temperatures of approximately 1300 °C; as described by Brandon and Taylor (Ref 10). Unlike the t-YSZ phase, the t’-YSZ phase does not undergo the unwanted martensitic m-YSZ phase transformation described above. For this reason, the t’-YSZ phase is very desirable for a TBC. To properly identify the t’-phase is necessary to distinguish it from the regular tetragonal t-phase of YSZ. As both exhibit their 100% highest intensity diffraction peaks very close to each other, as per Fig. 6(a); it is necessary to look into a second zone of the XRD pattern, which is featured in Fig. 6(b). Essentially, the XRD peaks of the t’-phase and t-phase of YSZ will overlap along the pattern from 20° to 80° for the CuKα XRD radiation, except at the 2θ zone around 72-76°. The t’-YSZ phase will exhibit the diffraction peaks 004 and 220 at ~73.2° and ~74.2o (respectively); whereas the t-YSZ exhibits the diffraction peak 004/220 at ~73.7°. By looking at Fig. 6(b), it is realized that the YSZ powder has the t’-YSZ as the primary phase (with minor m-YSZ phase—Fig. 6a) and both YSZ TBCs only display the well-desired t’-YSZ phase in their compositions. More information about the importance of these YSZ phases, their formations and influence on TBC performance can be found in the work of Brandon and Taylor (Ref 10).

APS YSZ TBC Architectures: Thermal Gradients

As previously stated, TBCs reduce the temperature of the Ni-based metallic superalloy metallic components located in the hot section of gas turbine engines; which typically exhibit wall thicknesses of ~1–2 mm and melting points within the 1300-1400 °C range. According to Rolls-Royce (Ref 30), the maximum temperature that the hot gases inside combustion chamber can reach is 2000 °C (at its flame core). This gas temperature is subsequently and progressively cooled by cold air that is bled from the turbine compressor and injected along the combustor length (via dilution holes) to reach its specified turbine inlet temperature (TIT). The TIT is the temperature of the combustion gases that leave the combustion chamber and enter the turbine unit.

It needs to be stressed that a turbine engine does not always operate at its peak temperatures. For example, according to the report Commercial Aircraft Propulsion and Energy Systems Research: Reducing Global Carbon Emissions (Ref 31), aviation turbine engines operate at different power levels during each of the distinct segment of a flight. For example, the turbines of commercial jet liners at the take-off will operate at 100% of their peak power (which will last for no more than 5 min), whereas, during longest stage of the flight (i.e., cruise), they will operate at 30% of the maximum power. Regarding fighter jets, Mom and Hersback (Ref 32) exemplified that depending on the mission (e.g., from general flying to “dog-fight” mode), maximum military turbine power can be applied from few to several times during a flight mission. According to Farokhi (Ref 33), the TIT levels of modern jet engines during take-off (i.e.; max power) are reaching the range of 1500-1600 °C; whereas these TIT levels during the cruise stage are found within the 1140-1240 °C range. Regarding IGTs, Nelson and Orenstein (Ref 34) explained that they will operate at lower maximum peak temperatures than those of aviation turbines, but at much longer and continuous times (>20,000 h). As a complement note, YSZ TBCs are not supposed to temperatures higher than ~1300 °C, as discussed in "Understanding Thermal Gradients within TBCs and Metallic Components" section , even if TIT levels reach 1500-1600 °C at take-off engine power. A thin air film cooling (bled from the compressor) will flow adjacent to the TBC surface from specifically engineered cooling holes in the components, thereby providing a “cooler shielding layer” over the TBC surface (in addition to the uncoated component backside), as described in details by Rolls-Royce (Ref 30) and Farokhi (Ref 33). Finally, Witz and Bossmann (Ref 29) analyzed ex-serviced real TBC-coated components of turbine engines. Their objective of the study was to determine the real surface temperature that TBCs were subjected during engine operation (via thermal paint and XRD analysis); in order to create mappings of the TBC thermal load and a lifetime evaluation model. One of the parts analyzed was a ~20 cm x ~20 cm TBC-coated heat-tile originating from the combustion chamber. Via a thermal paint evaluation along the length of the tile, it was observed that during the life of engine operation, the TBC on this single component had experienced a variation of maximum temperature of up 150 °C across its ~20 cm extent, with the max peak located around center of the tile. Thus, based on the examples above cited, one can realize that the knowledge of the temperature drop (i.e., reduction) provided by a TBC on a coated component, over a wide range of (i) component locations, (ii) TBC thicknesses and (iii) surface temperatures, is essential for modelling, simulation and lifetime prediction. And these sets of data are scarce in the open literature.

To help addressing this need, the data profiles of the two 14% porous APS YSZ TBC samples of this study generated by the laser-rig can be found in Fig. 7 (~420 µm-thick YSZ TBC) and Fig. 8 (~930 µm-thick YSZ TBC). It includes the YSZ TBC surface temperature (T-ysz), the substrate temperature (T-sub), the laser power and the back-side air cooling for the un-coated side of the coupons. Some important characteristics are shared for both testing. After an initial laser-rig stabilization period of ~2 min, the profiles generated were essentially constant for nearly 30 min. As stated, the back cooling air jet on the uncoated side of the coupons was set at ~430 lpm for all samples. Consequently, all these TBC-coated samples are being tested under virtually identical cooling conditions. For this reason, to increase T-ysz from 1100 °C to higher values, the laser power had to be increased. On the same note, the higher the T-ysz, the higher the T-sub (as expected). It is important to remember that the T-sub was measured via a thermocouple inserted the mid-thickness of the substrate, located 1.6 mm beneath the BC/substrate interface. Therefore, the T-sub values measured in this experiment are considered to be representative of those of a back-side component (e.g., combustion chamber), if its total wall thickness was 1.6 mm.

As all ΔTs for all TBCs in the individual testing conditions depicted in Fig. 7(a)-(e) and 8(a)-(g) are consistent and steady; i.e., parallel to each other, it can be said that any significant YSZ sintering/densification events that might have occurred, were minor and did not affect the experiment in some significant way. In other words, if a significant YSZ sintering was taking place during testing, the T-ysz and T-sub profiles would become tapered towards each other. On that account, it is fair to say that the data reported in this work (Fig. 7-8) represent the ΔT temperature reduction values that occur across TBC/substrate systems for an as-sprayed 14% porous APS YSZ TBC, manufactured at two thickness levels and subjected to distinct T-ysz values but the same cooling.

As explained in the "YSZ Elastic Modulus via Instrumented Indentation Testing" section of this manuscript, the T-ysz was increased from 1100 °C in 100 °C steps (by augmenting laser power) until the temperature of the substrate (T-sub) reached around 1000 °C; which is typically considered to be the highest limit of temperature operation for static gas turbine components (e.g., combustor). Figure 9 and 10 highlight in more detail the data displayed in Fig. 7 and 8.

For example, Fig. 9 depicts the resulting T-sub values as a function of the pre-selected T-ysz levels for both TBCs. For the ~420 µm-thick YSZ TBC, when T-ysz is ~1300 °C (typically considered at the YSZ upper temperature limit), the resulting T-sub is ~875 °C; which is well below the generally accepted T-sub of 1000 °C. T-sub will only reach 1000 °C, when T-ysz approaches 1500 °C. On the other hand, for the ~930 µm-thick YSZ TBC, this 1000 °C T-sub max limit could not be reached. The reason was, the highest calibrated temperature of the laser-rig pyrometer was 1684 °C. Consequently, the laser power was elevated and stopped at 511 W, when T-ysz had reached ~1680 °C; which corresponded to a T-sub of ~880 °C (Fig. 8g).

The specific temperature drop levels (ΔTs) across the TBC/substrates thickness profile are featured in Fig. 10. Once again, when T-ysz is ~1300 °C for ~420 µm-thick YSZ TBC, the resulting temperature reduction to the substrate is ~425 °C. For ~930 µm-thick YSZ TBC, at the very same T-ysz of ~1300°C, the resulting temperature reduction to the substrate is ~600 °C. These results point up the higher thermal resistance displayed by the thicker coating, as discussed by Helminiak et al. (Ref 15). And although YSZ TBCs were not developed to work at a T-ysz of 1680 °C, for sure one cannot fail to notice the “remarkable” temperature reduction of 800 °C to the substrate yielded by the thicker TBC (Fig. 10).

Finally, based on the references discussed above, it is important to remember again that gas turbine engines operate at different temperature regimes and the thermal load over TBC-coated component will vary depending on the part location. The TBC temperature mappings, such as that proposed by Witz and Bossmann (Ref 29), are very useful to pin-point temperature profiles and hot-spots. For these reasons, a better understanding of the ΔTs that take place along the TBC/component profile is of high importance for improving the manufacturing efficiency and lifetime of TBCs. For example, the thicknesses of the TBCs can be bespoken based on the previously-mapped thermal loads across the component. Most likely this approach could be “more easily” implemented in float wall type of combustion chambers. In this configuration, the walls of a combustor are lined by a multi-assembly of individual TBC-coated heat tiles that protect the body of the combustor liner from damage due to exposure with the hot gases.

YSZ TBC Manufacturing Cost Estimation

The high powder feed rate and DE values obtained for the YSZ TBC manufacturing reported in this manuscript can be considered very promising. However, one may claim that in real production environment, the elevated plasma gas flow levels and electrical energy consumption required by a high-enthalpy torch like the Axial III Plus would overshadow its gains when compared to the performance of a legacy torch.

To address this issue, the YSZ TBC manufacturing cost estimation was based on the data gathered during this study and also on results obtained in previous works (Ref 4, 5). The estimation was based on the calculation performed to spray a 410-430 µm thick YSZ TBC on a 500 mm long cylinder component, using spray parameters developed in this research for the Axial III Plus torch, as well as, that of a legacy APS Ar/H2 torch; which was sprayed a YSZ at powder feed rate of 60 g/min, displayed a porosity level of ~13% and exhibited a DE value of 43% (Ref 5). This component part could be considered as being similar to the inner wall of an annular turbine combustion chamber. The component tangential speed, the torch transverse speed, powder feed rate, DR and DE values used to estimate the cost and time to deposit the TBC were the ones used and obtained from these studies. The cost of the consumables and energy were: 30 US$/m3 for Ar, 22 US$/m3 for N2, 38 US$/m3 for H2, 34 US$/kg for YSZ feedstock and 0.25 kWh for electricity. Other costs involved (e.g., labor) were not included in the estimation.

Briefly, by changing from an Ar/H2 legacy plasma torch to a N2-based high-enthalpy one, there is a reduction of (i) 66% in processing time, (ii) 44% in YSZ feedstock consumption, (iii) 21% in plasma gas cost, (iv) 44% in electricity cost, and (v) 60% in total manufacturing cost. As previously stated, reducing environmental footprint means reducing at the same time the amount of natural resources and energy used to produce a product. Consequently, these sets of data exemplify the possible gains of manufacturing efficiency by using N2-based high-enthalpy APS torches for YSZ TBC production.

Final Comments

Regarding manufacturing efficiency, although the results obtained in this work are promising, there are still important steps to be investigated in order to confirm the applicability of these types of high feed rate and high DE APS YSZ TBCs in industrial applications. Among these steps are (i) YSZ thermal conductivity measurements, (ii) erosion testing and (iii) TBC thermal cycling performance. Regarding thermal conductivity measurements, the as-sprayed YSZ value most likely will fall within those reported in the literature for 10-15% porous YSZ TBCs; i.e., 0.8-1.0 W/mK (Ref 1, 4, 5). Thus, no unexpected surprises should occur here. The same hypothesis can be stated for erosion testing; considering the fact that the TBC manufactured in this study exhibits a conventional porous microstructure. But for sure an investigation on the thermal cycling performance (including a comparison with a TBC benchmark) is paramount.

With respect to the thermal gradient study, it is recognized that TBCs will sinter in time in these thermal gradient conditions, as described by Zhu and Miller (Ref 35) when using a laser-rig to create thermal gradients on TBCs. Since thermal gradient tests, such as burner and laser-rig are time consuming (and thereby costly), in order to provide sufficient statistics of samples to develop TBC aging models, most likely the combination of thermal gradient testing and the Larson-Miller parameter will be necessary. Larson–Miller parameter describes the creep-like behavior of thermal conductivity increase with temperature and time for different materials. For TBC R&D, this concept has been introduced by Zhu and Miller (Ref 35) and further explored by Tan et al. (Ref 36).

Moreover, it needs to be stressed that this work is not claiming (at all) that APS YSZ TBCs can be safety operated at temperatures higher than 1300 °C for long hours in gas turbine engines. The reasons for this 1300 °C YSZ limitation are well-known, stated and discussed in "Understanding Thermal Gradients within TBCs 189 and Metallic Components" section. The objective here is to provide engineering data for a better comprehension on how hot-section components of gas turbine are protected by TBCs. Consequently, a wide range of T-ysz values were investigated, including the ones above the 1300 °C limit. It is another complement to previous study (Ref 14), where (i) the same laser-rig equipment was employed to generate thermal gradients on porous APS YSZ TBCs at a T-ysz magnitude of 1300 °C and (ii) other TBC thermal gradient results reported in the literature were summarized.

Finally, by looking at the results of the thicker YSZ TBC (Fig. 8, 9, 10), one may wonder or even speculate about a possible thermal insulation protection that a thick (e.g., ~900-1000 µm) and porous (e.g., 10-20%) multi-layer TBC assembly could offer to these metallic components. A TBC assembly, which one of the layers could even be YSZ, but with the addition to other newly-developed over-layers. New high-performance ceramics engineered to display at high temperatures a combination some key characteristics; including (i) low thermal conductivity, (ii) phase stability, (iii) CMAS-attack resistance, (iv) erosion resistance and (iv) chemical endurance against water vapor attack. If achievable, this type of multi-layer TBC assembly could potentially operate at temperatures well-over the established 1300 °C limit for YSZ and still keep the current Ni-based superalloy components at temperatures no higher than 1000 °C. And if attainable, this type of multi-layer TBC assembly and Ni-based superalloy architecture may possibly be an alternative to environmental barrier coatings (EBCs) and ceramic matrix composites (CMCs).

Conclusions

This engineering paper demonstrated that a high-enthalpy N2-based APS torch (Axial III Plus) can be successfully employed to manufacture a conventional ~14% porous YSZ TBC at high powder feed rate (100 g/min) and DE value (70%). Two YSZ TBCs displaying thicknesses of ~420 and ~930 µm were deposited using the identical set of optimized spray parameters over the same type of ~160 µm-thick MCrAlY APS bond-coated coupons. Both YSZ TBCs did not show segmented cracking, horizontal inter-layer delamination or adhesion defects. In fact, the bond strength levels (ASTM C633) were 13 MPa (~420 µm-thick TBC) and 11.6 MPa (~930 µm-thick TBC); which are among the upper adhesion values for APS YSZ TBCs reported in the literature (i.e., typically 7-15 MPa). Therefore, even though one YSZ TBC is twice thicker than the other, the drop of bond strength intensity for the thicker coating was only 11%. Regarding phase composition, the two TBCs exhibited solely the desirable t’-phase of YSZ.

With respect to the thermal insulating effectiveness of as-sprayed ~14% porous APS YSZ TBCs, the following results are highlighted. The thermal gradient laser-rig data have shown that for the ~420 µm-thick YSZ TBC at YSZ surface temperatures (T-ysz) ranging from 1100 to 1500 °C, the resulting substrate temperatures (T-sub) values stretched from 750 to 1000 °C. For the ~930 µm-thick YSZ TBC, the YSZ surface temperature (T-ysz) level was extended from 1100 up to 1680 °C; and the resulting substrate temperatures (T-sub) varied from 600 to 880 °C. The ΔT results confirm the higher thermal resistance of the thicker YSZ when both TBCs operate within the same T-ysz reach. In addition, at a T-ysz of 1680 °C, the ~930 µm-thick YSZ TBC yielded temperature reduction of 800 °C to the substrate. It is thought that these results will be important for engineers working on the modelling/simulation of the performance and longevity of TBC-coated turbine components.

Although further investigation (e.g.; thermal cycling performance) is necessary to confirm the applicability of these TBCs in industrial environments; the initial results of this work are promising regarding the possibility of improving considerably the manufacturing efficiency of porous YSZ TBCs by using a high-enthalpy N2-based APS torch.

References

A. Feuerstein, J. Knapp, T. Taylor, A. Ashary, A. Bolcavage and N. Hitchman, Technical and Economical Aspects of Current Thermal Barrier Coating Systems for Gas Turbine Engines by Thermal Spray and EBPVD: A Review, J. Therm. Spray Technol., 2008, 17(2), p 199–213.

S. Sampath, U. Schulz, M.O. Jarligo and S. Kuroda, Processing Science of Advanced Thermal-Barrier Systems, MRS Bull., 2012, 37(7), p 903–910.

B.R. Marple, R.S. Lima, C. Moreau, S.E. Kruger, L. Xie and M.R. Dorfman, Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia Thermal Barriers Sprayed Using N2–H2 and Ar-H2 Plasmas: Influence of Processing and Heat Treatment on Coating Properties, J. Therm. Spray Technol., 2007, 16(5–6), p 791–797.

R.S. Lima, B.M.H. Guerreiro, N. Curry, M. Leitner and K. Körner, Environmental, Economical, and Performance Impacts of Ar-H2 and N2–H2 Plasma-Sprayed YSZ TBCs, J. Therm. Spray Technol., 2020, 29(1–2), p 74–89.

B.M.H. Guerreiro, R.S. Lima, N. Curry, M. Leitner and K. Körner, The Influence of Plasma Composition in the Thermal Cyclic Performance of Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia (8YSZ) Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs), J. Therm. Spray Technol., 2021, 20(1–2), p 59–68.

V. Belashchenko and A. Zagorski, “High Stability, High Enthalpy APS Process Based on Combined Wall and Gas Stabilizations of Plasma (Part 2: Plasma Properties and Process Operating Window)”, Proceedings of the International Thermal Spray Conference, May 11-14, 2015, Long Beach, CA, USA, (Ed.) A. McDonald, A. Agarwal, G. Bolelli, A. Concustell, Y.–C. Lau, F.-L. Toma, E. Turunen and C. Wildener, ASM International, Materials Park, OH, USA, p 184-191, 2015

A.B. Murphy and C.J. Arundell, Transport Coefficients of Argon, Nitrogen, Oxygen, Argon-Nitrogen, and Argon-Oxygen Plasmas, Plasma Chem. Plasma Process., 1994, 14(4), p 451–490.

A. El-Zein, M. Talaat, G. El-Aragi and A. El-Amawy, Electrical Characteristics of Nonthermal Gliding Arc Discharge Reactor in Argon and Nitrogen Gases, IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci., 2016, 44(7), p 1155–1159.

M.P. Borom, C.A. Johnson and L.A. Peluso, Role of Environmental Deposits and Operating Surface Temperature in Spallation of Air Plasma Sprayed Thermal Barrier Coatings, Surf. Coat. Technol., 1996, 86–87, p 116–126.

J.R. Brandon and R. Taylor, Phase Stability of Zirconia-Based Thermal Barrier Coatings Part I: Zirconia-Yttria Alloys, Surf. Coat. Technol., 1991, 46, p 75–90.

J.A. Thompson and T.W. Clyne, The Effect of Heat Treatment on the Stiffness of Zirconia Top Coats in Plasma-sprayed TBCs, Acta Mater., 2001, 49, p 1565–1575.

R. Vaßen, S. Giesen and D. Stover, Lifetime of Plasma-Sprayed Thermal Barrier Coatings: Comparison of Numerical and Experimental Results, J. Therm. Spray Technol., 2009, 18(5–6), p 835–845.

High-Temperature High-Strength Nickel Base Alloys, 2021, https://fdocuments.in/download/no-393-nickel-inst-mediafilestechnicalliteraturehighno-393-subject-high-temperature

R.S. Lima, Perspectives on Thermal Gradients in Porous ZrO2-7–8 wt.% Y2O3 (YSZ) Thermal Barrier Coatings (TBCs) Manufactured by Air Plasma Spray (APS), Coatings, 2020, 10(812), p 1–18.

M.A. Helminiak, M.N. Yanar, F.S. Pettit, T.A. Taylor and G.W. Meier, Factors Affecting the Microstructure Stability and Durability of Thermal Barrier Coatings Fabricated by Air Plasma Spraying, Mater. Corros., 2012, 63(10), p 929–939.

ASTM C633 - Standard Test Method for Adhesion or Cohesion Strength of Thermal Spray Coatings, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, USA.

W.C. Oliver and G.M. Pharr, Measurement of Hardness and Elastic Modulus by Instrumented Indentation: Advances in Understanding and Refinements to Methodology, J. Mater. Res., 2004, 19(1), p 3–20.

L. González-Fernández, L. del Campoa, R.B. Pérez-Sáeza and M.J. Telloa, Normal Spectral Emittance of Inconel 718 Aeronautical Alloy Coated with Yttria Stabilized Zirconia Films, J. Alloy. Compd., 2012, 513, p 101–106.

A. Schmidt, H. Aleksanoglu, T. Mao, A. Scholz and C. Berger, Influence of Bond Coat Roughness on Life Time of APS Thermal Barrier Coatings Systems under Thermal-Mechanical Load, J. Solid Mech. Mater. Eng., 2010, 4(2), p 208–220.

R. Eriksson, S. Sjöström, H. Brodin, S. Johanssona, L. Östergrenc and X.-H. Li, TBC Bond Coat-Top Coat Interface Roughness: Influence on Fatigue Life and Modelling Aspects, Surf. Coat. Technol., 2013, 236, p 230–238.

J.A. Haynes, M.K. Ferber and W.D. Porter, Thermal Cycling Behavior of Plasma-Sprayed Thermal Barrier Coatings with Various MCrAIX Bond Coats, J. Therm. Spray Technol., 2000, 9(1), p 38–48.

H.P. Bossmann, G. Witz and R. Baumann, Development of Reliable Thermal Barrier Coatings for high-loaded Turbine and Combustor Parts, VGB PowerTech, 2011, 91(10), p 50–54.

R. Vaßen, F. Traeger and D. Stöver, Correlation Between Spraying Conditions and Microcrack Density and Their Influence on Thermal Cycling Life of Thermal Barrier Coatings, J. Therm. Spray Technol., 2004, 13(3), p 396–404.

S.V. Shinde, E.J. Gildersleeve, C.A. Johnson and S. Sampath, Segmentation Crack Formation Dynamics During Air Plasma Spraying of Zirconia, Acta Mater., 2020, 183, p 196–206.

J. Smith, J. Scheibel, D. Classen, S. Paschke, S. Elbel, K. Fick and D. Carlson, Thermal Barrier Coating Validation Testing for Industrial Gas Turbine Combustion Hardware, J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power, 2016, 138(3), p 215–220.

N. Curry, M. Leitner and K. Körner, High-Porosity Thermal Barrier Coatings from High-Power Plasma Spray Equipment—Processing Performance and Economics, Coatings, 2020, 10(957), p 1–25.

P.-H. Lee, S.-Y. Lee, J.-Y. Kwon, S.-W. Myoung, J.-H. Lee, Y.-G. Jung, H. Cho and U. Paik, Thermal Cycling Behavior and Interfacial Stability in Thick Thermal Barrier Coatings, Surf. Coat. Technol., 2010, 205, p 1250–1255.

S.-W. Myoung, Z. Lu, Y.-G. Jung, B.-K. Jang, Y.-S. Yoo, S.-M. Seo, B.-G. Choi and C.-Y. Jo, Effect of Plasma Pretreatment on Thermal Durability of Thermal Barrier Coatings in Cyclic Thermal Exposure, Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng., 2014 https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/593891

G. Witz and H.-P. Bossmann, Determination of Thermal Barrier Coatings Average Surface Temperature After Engine Operation for Lifetime Validation, J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power, 2012, 134, p 122507-1–7.

Rolls-Royce. The Jet Engine, (2020), http://www.valentiniweb.com/Piermo/meccanica/mat/Rolls%20Royce%20%20The%20Jet%20Engine.pdf

Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine—Commercial Aircraft Propulsion and Energy Systems Research: Reducing Global Carbon Emissions, (2020), https://www.nap.edu/catalog/23490/commercial-aircraft-propulsion-and-energy-systems-research-reducing-global-carbon

A. Mom and H. Hersbach, Performance of High Temperature Coatings on F100 Turbine Blades Under Simulated Service Conditions, Mater. Sci. Eng., 1987, 87, p 361–367.

S. Farokhi, Aircraft Propulsion, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Chichester, West Sussex, UK, pp. 7–9, p 483–488 (2015)

W.A. Nelson and R.M. Orenstein, TBC Experience in Land-Based Gas Turbines, J. Therm. Spray Technol., 1997, 6, p 176–180.

D. Zhu and R.A. Miller, Thermal Conductivity and Elastic Modulus Evolution of Thermal Barrier Coatings under High Heat Flux Conditions, J. Therm. Spray Technol., 2000, 9, p 175–180.

Y. Tan, J.P. Longtin, S. Sampath and H. Wang, Effect of the Starting Microstructure on the Thermal Properties of As-sprayed and Thermally Exposed Plasma-Sprayed YSZ Coatings, J. Am. Ceram. Soc., 2009, 92(3), p 710–716.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the contribution of the following Technical Officers (TOs) of the NRC: David Delagrave for metallography preparation and Karine Théberge for SEM-EDX and instrumented indentation evaluation. NRC’s Associate Research Officer (AcSO) Bruno Guerreiro help in operating the XRD equipment is highly appreciated. Finally, very special thanks to the NRC TO Jean-Claude Tremblay for (i) commissioning the Axial III Plus APS torch at the NRC, (ii) TBC manufacturing and (iii) thermal gradient laser-rig testing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lima, R.S. Porous APS YSZ TBC Manufactured at High Powder Feed Rate (100 g/min) and Deposition Efficiency (70%): Microstructure, Bond Strength and Thermal Gradients. J Therm Spray Tech 31, 396–414 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11666-021-01302-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11666-021-01302-y