Abstract

Thermal spraying using liquid feedstock can produce coatings with very fine microstructures either by utilizing submicron particles in the form of a suspension or through in situ synthesis leading, for example, to improved tribological properties. The focus of this work was to obtain a bimodal microstructure by using simultaneous hybrid powder-precursor HVOF spraying, where nanoscale features from liquid feedstock could be combined with the robustness and efficiency of spraying with powder feedstock. The nanostructure was achieved from YSZ and ZrO2 solution-precursors, and a conventional Al2O3 spray powder was responsible for the structural features in the micron scale. The microstructures of the coatings revealed some clusters of unmelted nanosized YSZ/ZrO2 embedded in a lamellar matrix of Al2O3. The phase compositions consisted of γ- and α-Al2O3 and cubic, tetragonal and monoclinic ZrO2. Additionally, some alloying of the constituents was found. The mechanical strength of the coatings was not optimal due to the excessive amount of the nanostructured YSZ/ZrO2 addition. An amount of 10 vol.% or 7 wt.% 8YSZ was estimated to result in a more desired mixing of constituents that would lead to an optimized coating architecture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Thermally sprayed ceramic coatings are typically used in the aerospace industry for their low thermal diffusivity and high-temperature erosion resistance. Other applications are found, e.g., in components in the process industry, such as center rolls and dewatering elements for paper machines, mechanical seals and process valves (Ref 1). In these components, combined wear- and corrosion resistance is the key factor and the main reason for choosing ceramic coatings over other material options. However, typically brittle behavior and interlamellar cracking prevent their use in many applications (Ref 2).

Al2O3 is a widely used ceramic material in thermal spraying due to its low cost and various favorable properties, such as resistance to abrasive and sliding wear, and high dielectric strength (Ref 3, 4). However, its tribological properties are not up to par with other ceramic coatings, such as Cr2O3 (Ref 5), in more demanding conditions. In a technical perspective, a vast amount of research has gone into improving the fracture toughness of Al2O3 with additions of ZrO2, with the intent of strengthening the composite. This can be achieved by the well-known toughening effect of the phase transformation of tetragonal ZrO2 to monoclinic and the following volume change as well as the ferroelastic domain switching in tetragonal ZrO2 (Ref 6,7,8,9,10). An undesirable side effect of the phase change is a large volume increase, which deteriorates the coating integrity. However, it can be countered by stabilizing the ZrO2 to either non-transformable tetragonal or cubic phases by adding stabilizing oxides, such as MgO (resulting in MSZ, magnesia-stabilized zirconia) or Y2O3 (leading to YSZ, yttria-stabilized zirconia). This practice is already widely utilized in top coats of thermal barrier coatings, where the coatings resistance to catastrophic failure is critical due to immense cyclic thermo-mechanical loading (Ref 1, 11).

While improvements are usually gained in the tribological behavior of thermally sprayed Al2O3-YSZ coatings, no evidence of toughening has been found, though some studies claim the transformation is the cause for the improved wear behavior (Ref 12, 13). Sometimes, however, the improvement is attributed to the lower melting point and better cohesion of the coating (Ref 14). We have previously studied the effect of this phase change in conventional thermally sprayed Al2O3-40ZrO2 coatings as well, but the toughening was not evident (Ref 15, 16).

Nanocrystalline structures have been achieved in thermal spraying using suspension- and solution-precursor feedstocks (Ref 13, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24), indicating the potential of novel processing routes in achieving the desired toughness increase. The toughening was achieved without compromising structural cohesion, for example, by increasing the crack propagation resistance when small unmelted ZrO2 particles are preserved in the coating matrix (Ref 13). However, alloying Al2O3 with ZrO2 is challenging in thermal spraying of nanoscale feedstock as the composition can easily lead to the formation of an amorphous phase during processing that deteriorates mechanical properties due to a reduction in available slip planes leading to increased brittleness (Ref 13, 25).

HVOF spraying of ceramics requires a combustible gas capable of producing a high flame temperature with oxygen to produce the energy required to melt the material. Due to the restriction of available energy combined with high velocities leading to short dwell times, the HVOF system is mainly used with low-melting ceramics, such as TiO2 (Ref 26) or Al2O3 (Ref 27). For higher melting materials, such as ZrO2, particle size is the key between achieving a coating by melting or partly melting and partly sintering the material (Ref 28).

Solution-precursor HVOF (SP-HVOF) spraying is a novel spray process, in which coating formation through in-flight nanoparticle synthesis and subsequent melting is attainable. The size of the synthesized particles in SP-HVOF is 10-500 nm (Ref 29). However, creating a thick, cohesive coating with SP-HVOF is not only tedious due to the relatively low deposition rate, but also difficult due to the necessity to melt the particles to form the coating without inducing excessive grain growth. This problem has been tackled by Joshi et al. (Ref 30) by utilizing a hybrid plasma spray, where solution and powder are being fed simultaneously into the plasma, forming a coating of micron-sized lamellae from powder particles with nanosized particles originating from the solution in the splat boundaries. The coatings provided the best properties of both processes: The high deposition rate of traditional plasma spraying of powder feedstock, along with the high hardness and density of solution-precursor plasma-sprayed coatings. More recently, Goel et al. (Ref 31) have employed the same philosophy in depositing an Al2O3-YSZ coating from Al2O3 powder and an 8YSZ suspension with an axial plasma spray process, providing a higher wear resistance with the introduction of the suspension into the process. Similarly, Murray et al. (Ref 32) showed increased fracture toughness and lower wear rate of powder-suspension and suspension-suspension-sprayed Al2O3-YSZ coatings sprayed with the same system when compared to either powder- or suspension-sprayed Al2O3.

In this study, the feasibility of a hybrid HVOF process utilizing a powder with a second feedstock, in this case solution-precursor, is examined for Al2O3-YSZ/ZrO2 composite coatings. The goal is to be able to deposit nanosized YSZ/ZrO2 particles at the splat boundaries between the Al2O3 splats to bind the splats together and, thus, improve the mechanical properties of the coatings. Two separate variables were studied: the effect of the amount of YSZ (0, 20 and 40 wt.%), and the effect of stabilization of the ZrO2. The coating microstructures were characterized by FESEM and XRD, and their mechanical properties, hardness and cavitation erosion resistance were measured.

Experimental Methods

Coating Preparation

The powder feedstock material for the alumina (Al2O3) component was Amperit 740.001 (− 25 + 5 µm) (H. C. Starck GmbH, Munich, Germany). The yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) solutions were manufactured by mixing a saturated water-based solution (at 20 °C) of yttrium(III)nitrate hexahydrate (Acros organics/Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Geel, Belgium) and a 16 wt.% zirconium acetate solution in dilute acetic acid (Sigma-Aldrich/Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) in proper ratios to achieve 8 wt.% of yttria in zirconia after pyrolysis in the flame to create stabilized tetragonal zirconia (8YSZ). One solution was prepared without adding yttria in order to examine the effect of stabilization of the zirconia.

The coatings were sprayed with a TopGun HVOF system (GTV GmbH, Luckenbach, Germany) modified for liquid feedstock spraying, using ethene as a fuel gas and oxygen as an oxidant on 50 × 100 × 5 mm substrates of stainless steel (AISI 316) that were grit-blasted with 180-220 mesh alumina prior to deposition. The powder feedstock was fed with a commercial 9MP powder feeder (Oerlikon Metco AG, Wohlen, Switzerland), and the solution was fed with a diaphragm pump feeder made in-house, that was equipped with a closed-loop mass-flow meter to stabilize the solution flow rate. The powder and the liquid precursor were injected in the same injector where they were mixed and injected together into the combustion chamber. Atomizing of the mixture was brought about by the carrier gas of the powder. The feeding setup is explained in detail by Björklund et al. (Ref 33). The processing parameters were optimized in preliminary studies and are listed in Table 1. A schematic of the hybrid powder-precursor HVOF spray process is presented in Fig. 1.

Coating Characterization

The coatings were characterized with field emission scanning electron microscopes (FESEM) (Zeiss ULTRAplus and Zeiss Crossbeam 540, Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany). The FIB cross section and consequent analysis were performed with a Helios Nanolab 600 (FEI Company/Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Hillsboro, OR, United States). Compositional analyses of the coated surfaces were carried out using Inca x-act 350 energy-dispersive spectrometer (EDS) attached to the FESEM (ULTRAplus) and the phase analysis with x-ray diffraction (XRD, Empyrean, PANalytical, Cu-Kα radiation, The Netherlands).

Mechanical Characterization

The coating hardness was determined from ten indentations on the coating cross section using a Vickers hardness tester (MMT-X7, Matsuzawa Co., Ltd., Akita, Japan) with a load of 300 gf (HV0.3). The cavitation erosion test was performed with an ultrasonic transducer (VCX-750, Sonics and Materials Inc., Newtown, CT, USA), according to the ASTM G32-10 standard for indirect cavitation erosion. The vibration tip, made of a Ti-6Al-4V alloy, was vibrating at a frequency of 20 kHz with an amplitude of 50 µm at a distance of 500 µm from the surface. The sample surfaces were ground flat and polished with a polishing cloth and diamond suspension (3 μm). The samples were cleaned in an ultrasonic bath with ethanol and weighed after drying. Samples were attached on a stationary sample holder, and the head of the ultrasonic transducer was placed at a distance of 0.5 mm. Samples were weighed after 15, 30, 60 and 90 min. One sample per coating was tested. The long duration and high impact frequency of the test lend credibility to sufficient statistical certainty. Cavitation resistance of the coatings was calculated as the reciprocal of the mean depth of erosion per hour, which in turn is derived from the theoretical volume loss (presuming a fully dense coating) and the area of the vibrating tip.

Results and Discussion

Microstructural Characterization

The cross sections of the coatings are presented in Fig. 2 and in higher magnification in Fig. 3. The coatings adhered well to the substrate, and in all hybrid coatings bimodality was achieved with in situ synthesized YSZ/ZrO2 particles of < 200 nm embedded between the well-melted Al2O3 splats. The coating structures seemingly have some apparent porosity; however, it is likely stemming from pullouts, i.e., the removal of poorly bonded particles or agglomerates during the sample preparation. According to the cross-sectional images, the synthesized nanoparticles obtained a round morphology indicating partially molten state, but a majority of the nanoparticles were not well integrated to the alumina splats, as presented in Fig. 4(a). In addition, some mixed-phase areas were found, shown as the light gray areas in Fig. 4(b). This indicates the possibility of strengthening the traditional powder-sprayed coating structure by interlocking the microscale splats, as the nanosized ceramics (with a very large surface area) enhance the diffusion of atoms in splat-nanoparticle interface (Ref 34). Additionally, since it has been shown that reducing the primary particle size to the nanoscale can lead to significant reductions in the sintering temperature in stabilized ZrO2 (Ref 35), some amount of sintering and enhanced diffusion could occur during spraying. Therefore, in optimal conditions, the sintered YSZ could be chemically bonded by diffusion/mixed phase with surrounding Al2O3 splats, leading to an extremely coherent structure. Some amount of unmelted nanoparticles can potentially also improve the toughness and wear resistance of the coating when the nanostructured zones are well embedded in the coating and act as crack arresters (Ref 36).

The EDS analyses of the coatings are presented in Table 2. The amount of ZrO2 was about half of the nominal amount from the feedstock. The low deposition efficiency of ZrO2 in comparison with Al2O3 can be attributed to its higher melting point as well as small particle size, leading to particles drifting along with the gas flow away from the substrate due to the high stagnation pressure zone near the surface slowing the particles down (bow-shock effect) and drag along the surface (Ref 37,38,39). Further optimization of the process parameters should improve this aspect along with decreasing the amount of unmelted YSZ/ZrO2 particles.

The EDS map of the coating A40Y is presented in Fig. 5. As expected from the contrast in the FESEM images, the bright areas consist of YSZ and darker areas of Al2O3. A mixed-phase area exists with a grayish color that can be verified from the EDS map, consisting of oxides of both aluminum and zirconium. In order to confirm that the mixed color did not arise from a brighter layer of zirconia under a darker layer alumina, FIB-FESEM studies were carried out. The sample was inspected from a FIB-milled cross section, where a light gray area was located, and the sample was subsequently milled from that plane on two more times, 2 µm at a time, as displayed in Fig. 6. It was ensured that the mixed-phase splat was indeed continuous also in the third dimension and not an artifact from the penetration depth of the electrons.

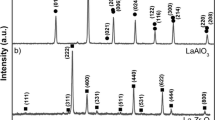

The x-ray diffraction patterns are presented in Fig. 7. As expected, the ZrO2 in the stabilized Al2O3-YSZ coatings was in the tetragonal form. A40Z consisted also of monoclinic and cubic ZrO2, which was unexpected since the stable phase of ZrO2 in room temperature is monoclinic. The occurrence of all the phases of ZrO2 in the unstabilized coating can be explained either by their metastability or by the size dependence of the phase transformations: For example, cubic ZrO2 stays stable in room temperature with crystallite sizes < 2 nm (Ref 40, 41). Al2O3 was in all cases as α- and γ-phases, as is typical in HVOF spraying of Al2O3, where the core of some particles of the feedstock-powder presumably does not melt and stays as α-phase. Interestingly, amorphous compounds, which are a common product of thermal spraying Al2O3-ZrO2 mixtures from powder (Ref 16, 25), were not found in significant quantities.

Mechanical Properties

Coating hardnesses were decreased by the addition of YSZ/ZrO2 in Al2O3, as presented in Table 3. However, the reduction in hardness was moderate in the case of A20Y, indicating the possibility to achieve a dense structure even with the addition of nanoparticles, as also evidenced by Goel et al. (Ref 31). The coatings with 40 wt.% nominal addition of YSZ/ZrO2 underwent a more severe reduction in hardness, as could be predicted from the large clusters of nanoparticles between the splats as seen in all hybrid coatings in the cross sections in Fig. 3 and in detail for A40Y in Fig. 4; the cohesion of the coatings was reduced as compared to the reference.

Cavitation erosion resistance is typically a good measure of the cohesion of thermally sprayed coatings, and it is able to reveal weak links in the microscale (Ref 15, 42). The experiment revealed structural weakness in the hybrid powder-precursor-sprayed coatings: Similarly to the hardness values, a reduction in cavitation resistance was observed with increasing amounts of YSZ/ZrO2, as can be observed in Fig. 8. However, this time the reduction is significant, dropping to less than half with 20 wt.% YSZ and to less than a quarter with 40 wt.% YSZ and ZrO2 additions as compared to pure Al2O3. This is supported by Fig. 9, where surface images of A40Y are presented as-sprayed and after the test. Clearly, there are vast amounts of YSZ nanoparticles on top of the surface (Fig. 9a), like was seen between the splats as well (Fig. 4a), that impair the cohesion of the coating, which is most exposed under fatiguing conditions. These particles were removed during the experiment, as can be seen from their lesser amount in Fig. 9(b), where mainly larger well-melted splats are visible. The cavitation erosion resistance is typically favored by good cohesion and small splat size of the formed coating, while nonintegrated particles are readily attacked and act as concentration sites for the erosion (Ref 15, 42). The hybrid HVOF-sprayed coatings aimed to achieve these beneficial qualities but missed the goal as the nanoparticles were not successfully embedded in the coating and an insufficient amount of mixed-phase regions were created to strengthen the coating. These results are contradictory to, for example, the results of Murray et al. (Ref 32) who were able to increase the wear resistance in dry-sliding ball-on-flat test of the reference Al2O3 coating by the addition of YSZ suspension. The test conditions were 30 min with a 6.3-mm-diameter alumina ball, a load of 10 N and a sliding speed of 10 mm/s. In their case, however, the major difference was that an axial-feed plasma-spray system was used, which has enough power to melt the YSZ particles from the suspension and there was no detrimental nonintegrated particles embedded in the coating. Additionally, the scale in their test is some orders of magnitude larger since the cavitating bubbles, being a few tens of microns, mainly nucleate on surface asperities and cavities of similar size (Ref 43). The tests measure, thus, somewhat different features.

Tailoring Possibilities of the Coating Architecture

In order to evaluate the next steps to optimize the coating architecture, calculations were performed on black/white histograms of a cross-sectional image (as visualized in Fig. 10) of the pure Al2O3 coating to obtain the amount of horizontal vacancies between the lamellae. These vacancies could be filled with the nanosized YSZ/ZrO2 particles or the Al2O3-YSZ/ZrO2 mixed phase in order to increase the structural integrity of the coating. Theoretically, packing the interlamellar vacancies with a sufficient amount of nanoparticles while avoiding overpacking would lead to the densest achievable coating with optimal properties, as pictured in Fig. 10(b). Five vertical areas of the image were selected, and the area fraction of interlamellar vacancies to lamellae is calculated from a black/white histogram, Fig. 10(c). By selecting narrow, vertical areas from regions with few vertical cracks, we aim to isolate the horizontal vacancies between the lamellae, which are desirable to be filled. An average of 10 vol.% of horizontal vacancies/splat boundaries was determined, which translates to a theoretically optimal mixture of 7 wt.% of the 8YSZ solution and 93 wt.% Al2O3 powder. This is not far from the actual amount obtained from A20Y due to the lower deposition efficiency of YSZ. Hence, a coating with this or lower ratio should be manufactured and evaluated in the next phase of the study, in order to create a distinct enough difference to A20Y.

Drawing from the results of this study, future research should steer itself toward lower melting feedstock or additives in the solution, such as citric acid or acetic acid, to increase the exothermic nature of the synthesis reaction (Ref 44). By combining solution and powder feedstock in situ, it is possible to combine oxides into coatings jointly with other oxides, hard metals or metals of virtually any combination without the limitations of powder or suspension preparation, thereby obtaining novel functional properties for thermally sprayed coatings.

Conclusions

Preliminary results on the characterization of coatings prepared via a hybrid powder-precursor HVOF spray process were presented in this study. The coatings were manufactured from a solution of zirconium acetate and yttrium nitrate hexahydrate, and a commercial powder feedstock of Al2O3. Microscopic characterization techniques were used to investigate the formed microstructures, and cavitation erosion was utilized to evaluate the cohesion and structural integrity of the coating.

The coating structures were macroscopically dense and bimodal, with nanosized YSZ/ZrO2 particles and agglomerates thereof occupying the interlamellar regions between the Al2O3 splats, along with some mixed phase of Al2O3-YSZ/ZrO2. However, the addition of YSZ/ZrO2 lowered the hardness of the coating slightly. The cause was determined to be the areas with agglomerates of unmelted YSZ/ZrO2 that were also found to weaken the coating in cavitation erosion, which tests the structural integrity and cohesion of the coating through fatigue from microscopic impacts. Thus, the desired improvement in mechanical properties was not achieved yet. The role of Y2O3 in stabilizing t-ZrO2 as compared to unstabilized ZrO2 had no effect on the hardness or cavitation resistance of the coating with the current achieved microstructure.

The usability of the novel hybrid powder-precursor HVOF process has been successfully demonstrated, and with further process optimization the composition is believed to provide interesting results. The results implicate that by reducing the amount of solution-precursor-synthesized YSZ/ZrO2, the coating cohesiveness would be sufficient to bring out the toughening effect of the added nanostructured phase. Based on the calculations of vacancies between splats in the Al2O3 coating, an optimal feedstock mixing ratio would be 7 wt.% of 8YSZ solution of the total feed presuming identical deposition efficiencies of the two feedstocks. Further studies are recommended to optimize the relationship between the feedstock and deposition parameters. Additionally, by utilizing different feedstocks with lower melting points than YSZ or ZrO2, it is foreseen to be possible to produce interesting nano-microcomposite coatings of various compositions with relative ease and reproducibility bringing material tailoring of thermally sprayed coatings to new levels.

References

P. Vuoristo, Thermal Spray Coating Processes, Comprehensive Materials Processing: Films and Coatings: Technology and Recent Development, Vol 4, S. Hashmi, Ed., Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2014, p 229-276

L. Pawlowski, The Science and Engineering of Thermal Spray Coatings, 2nd ed., Wiley, West Sussex, 2008

J. Ilavsky, C. Berndt, and H. Herman, Alumina-Base Plasma-Sprayed Materials—Part II: Phase Transformations in Aluminas, J. Therm. Spray Technol., 1997, 6(4), p 439-444

P.L. Fauchais, J.V.R. Heberlein, and M.I. Boulos, Thermal Spray Fundamentals, Springer, Boston, 2014

G. Bolelli, V. Cannillo, L. Lusvarghi, and T. Manfredini, Wear Behaviour of Thermally Sprayed Ceramic Oxide Coatings, Wear, 2006, 261(11-12), p 1298-1315

J. Chevalier, S. Deville, G. Fantozzi, J.F. Bartolomé, C. Pecharroman, J.S. Moya, L.A. Diaz, and R. Torrecillas, Nanostructured Ceramic Oxides with a Slow Crack Growth Resistance Close to Covalent Materials, Nano Lett., 2005, 5(7), p 1297-1301

J. Chevalier, A.H. De Aza, G. Fantozzi, M. Schehl, and R. Torrecillas, Extending the Lifetime of Ceramic Orthopaedic Implants, Adv. Mater., 2000, 12(21), p 1619-1621

E. Kannisto, M.E. Cura, E. Levänen, and S.P. Hannula, Mechanical Properties of Alumina Based Nanocomposites, Key Eng. Mater., 2012, 527, p 101-106

A. Evans, Perspective on the Development of High-Toughness Ceramics, J. Am. Ceram. Soc., 1990, 73(2), p 187-206

G.V. Srinivasan, J.F. Jue, S.Y. Kuo, and A.V. Virkar, Ferroelastic Domain Switching in Polydomain Tetragonal Zirconia Single Crystals, J. Am. Ceram. Soc., 1989, 72(11), p 2098-2103

R.A. Miller, Thermal Barrier Coatings for Aircraft Engines: History and Directions, J. Therm. Spray Technol., 1997, 6(1), p 35-42

G. Perumal, M. Geetha, R. Asokamani, and N. Alagumurthi, Wear Studies on Plasma Sprayed Al2O3-40wt% 8YSZ Composite Ceramic Coating on Ti-6Al-4V Alloy Used for Biomedical Applications, Wear, 2014, 311(1-2), p 101-113

J. Oberste Berghaus, J.-G. Legoux, C. Moreau, F. Tarasi, and T. Chráska, Mechanical and Thermal Transport Properties of Suspension Thermal-Sprayed Alumina-Zirconia Composite Coatings, J. Therm. Spray Technol., 2007, 17(1), p 91-104

Y. Bai, F.L. Yu, S.W. Lee, H. Chen, and J.F. Yang, Characterization of the Near-Eutectic Al2O3-40 wt% ZrO2 Composite Coating Fabricated by Atmospheric Plasma Spray. Part II: Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Nanocomposite Coating, Mater. Manuf. Process., 2012, 27(1), p 58-64

J. Kiilakoski, F. Lukac, H. Koivuluoto, and P. Vuoristo, Cavitation Wear Characteristics of Al2O3-ZrO2-Ceramic Coatings Deposited by APS and HVOF-Processes, in Proceedings of the ITSC 2017, June 7-9, 2017 (Düsseldorf, Germany), DVS Media GmbH (2017), pp. 928-933

J. Kiilakoski, R. Musalek, F. Lukac, H. Koivuluoto, and P. Vuoristo, Evaluating the Toughness of APS and HVOF-Sprayed Al2O3-ZrO2-Coatings by In-Situ- and Macroscopic Bending, J. Eur. Ceram. Soc., 2018, 38(4), p 1908-1918

D. Chen, E.H. Jordan, and M. Gell, Suspension Plasma Sprayed Composite Coating Using Amorphous Powder Feedstock, Appl. Surf. Sci., 2009, 255(11), p 5935-5938

D. Chen, E.H. Jordan, and M. Gell, Microstructure of Suspension Plasma Spray and Air Plasma Spray Al2O3-ZrO2 Composite Coatings, J. Therm. Spray Technol., 2009, 18(3), p 421-426

D. Chen, E.H. Jordan, and M. Gell, Solution Precursor High-Velocity Oxy-Fuel Spray Ceramic Coatings, J. Eur. Ceram. Soc., 2009, 29(16), p 3349-3353

G. Darut, H. Ageorges, A. Denoirjean, G. Montavon, and P. Fauchais, Effect of the Structural Scale of Plasma-Sprayed Alumina Coatings on Their Friction Coefficients, J. Therm. Spray Technol., 2008, 17(5-6), p 788-795

F.-L. Toma, L.-M. Berger, T. Naumann, and S. Langner, Microstructures of Nanostructured Ceramic Coatings Obtained by Suspension Thermal Spraying, Surf. Coat. Technol., 2008, 202(18), p 4343-4348

A. Killinger, M. Kuhn, and R. Gadow, High-Velocity Suspension Flame Spraying (HVSFS), a New Approach for Spraying Nanoparticles with Hypersonic Speed, Surf. Coat. Technol., 2006, 201(5), p 1922-1929

S. Govindarajan, R.O. Dusane, and S.V. Joshi, In Situ Particle Generation and Splat Formation During Solution Precursor Plasma Spraying of Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia Coatings, J. Am. Ceram. Soc., 2011, 94(12), p 4191-4199

J. Tikkanen, K.A. Gross, C.C. Berndt, V. Pitkänen, J. Keskinen, S. Raghu, M. Rajala, and J. Karthikeyan, Characteristics of the Liquid Flame Spray Process, Surf. Coat. Technol., 1997, 90(3), p 210-216

H.-J. Kim and Y.J. Kim, Amorphous Phase Formation of the Pseudo-Binary Al2O3-ZrO2 Alloy During Plasma Spray Processing, J. Mater. Sci., 1999, 34(1), p 29-33

R.S. Lima and B.R. Marple, From APS to HVOF Spraying of Conventional and Nanostructured Titania Feedstock Powders: A Study on the Enhancement of the Mechanical Properties, Surf. Coat. Technol., 2006, 200(11), p 3428-3437

C.C. Stahr, S. Saaro, L.M. Berger, J. Dubský, K. Neufuss, and M. Herrmann, Dependence of the Stabilization of α-Alumina on the Spray Process, J. Therm. Spray Technol., 2007, 16(5-6), p 822-830

T.A. Dobbins, R. Knight, and M.J. Mayo, HVOF Thermal Spray Deposited Y2O3-Stabilized ZrO2 Coatings for Thermal Barrier Applications, J. Therm. Spray Technol., 2003, 12(2), p 214-225

J. Puranen, J. Laakso, M. Honkanen, S. Heinonen, M. Kylmälahti, S. Lugowski, T.W. Coyle, O. Kesler, and P. Vuoristo, High Temperature Oxidation Tests for the High Velocity Solution Precursor Flame Sprayed Manganese-Cobalt Oxide Spinel Protective Coatings on SOFC Interconnector Steel, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy, 2015, 40(18), p 6216-6227

S.V. Joshi, G. Sivakumar, T. Raghuveer, and R.O. Dusane, Hybrid Plasma-Sprayed Thermal Barrier Coatings Using Powder and Solution Precursor Feedstock, J. Therm. Spray Technol., 2014, 23(4), p 616-624

S. Goel, S. Björklund, U. Wiklund, and S. V. Joshi, Hybrid Powder-Suspension Al2O3-ZrO2 Coatings by Axial Plasma Spraying: Processing, Characteristics & Tribological Behaviour, in Proceedings of the ITSC 2017, June 7-9, 2017 (Düsseldorf, Germany), DVS Media GmbH (2017), pp. 374-379

J.W. Murray, A. Leva, S. Joshi, and T. Hussain, Microstructure and Wear Behaviour of Powder and Suspension Hybrid Al2O3-YSZ Coatings, Ceram. Int., 2018, 44(7), p 8498-8504

S. Björklund, S. Goel, and S. Joshi, Function-Dependent Coating Architectures by Hybrid Powder-Suspension Plasma Spraying: Injector Design, Processing and Concept Validation, Mater. Des., 2018, 142, p 56-65

M.J. Mayo, Processing of Nanocrystalline Ceramics from Ultrafine Particles, Int. Mater. Rev., 1996, 41(3), p 85-115

W.H. Rhodes, Agglomerate and Particle Size Effects on Sintering Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia, J. Am. Ceram. Soc., 1981, 64(1), p 19-22

R.S. Lima and B.R. Marple, Enhanced Ductility in Thermally Sprayed Titania Coating Synthesized Using a Nanostructured Feedstock, Mater. Sci. Eng. A, 2005, 395(1-2), p 269-280

C. Qiu and Y. Chen, Manufacturing Process of Nanostructured Alumina Coatings by Suspension Plasma Spraying, J. Therm. Spray Technol., 2009, 18(2), p 272-283

K. Vanevery, M.J.M. Krane, R.W. Trice, H. Wang, W. Porter, M. Besser, D. Sordelet, J. Ilavsky, and J. Almer, Column Formation in Suspension Plasma-Sprayed Coatings and Resultant Thermal Properties, J. Therm. Spray Technol., 2011, 20(4), p 817-828

B. Samareh and A. Dolatabadi, A Three-Dimensional Analysis of the Cold Spray Process: The Effects of Substrate Location and Shape, J. Therm. Spray Technol., 2007, 16(5-6), p 634-642

E. Nouri, M. Shahmiri, H. Rezaie, and F. Talayian, The Effect of Alumina Content on the Structural Properties of ZrO2-Al2O3 Unstabilized Composite Nanopowders, Int. J. Ind. Chem., 2012, 3(1), p 17

S. Tsunekawa, S. Ito, Y. Kawazoe, and J.T. Wang, Critical Size of the Phase Transition from Cubic to Tetragonal in Pure Zirconia Nanoparticles, Nano Lett., 2003, 3(7), p 871-875

V. Matikainen, K. Niemi, H. Koivuluoto, and P. Vuoristo, Abrasion, Erosion and Cavitation Erosion Wear Properties of Thermally Sprayed Alumina Based Coatings, Coatings, 2014, 4(1), p 18-36

C.E. Brennen, Cavitation and Bubble Dynamics. Oxford Engineering Science Series, 1st ed., Oxford University Press Inc, New York, 1995

A.E. Danks, S.R. Hall, and Z. Schnepp, The Evolution of ‘Sol-Gel’ Chemistry as a Technique for Materials Synthesis, Mater. Horiz. R. Soc. Chem., 2016, 3(2), p 91-112

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the graduate school of the President of Tampere University of Technology and Business Finland (Finnish innovation funding, trade, investment and travel promotion organization), its “Ductile and Damage Tolerant Ceramic Coatings” project and the participating companies. The authors would like to thank colleagues from Tampere University of Technology: Mr. Mikko Kylmälahti for spraying the coatings and M.Sc. Jarmo Laakso and Dr. Mari Honkanen for the electron microscopy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kiilakoski, J., Puranen, J., Heinonen, E. et al. Characterization of Powder-Precursor HVOF-Sprayed Al2O3-YSZ/ZrO2 Coatings. J Therm Spray Tech 28, 98–107 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11666-018-0816-x

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11666-018-0816-x