Abstract

Background

Chronic pain is a prevalent health concern in the United States (US) and a frequent reason for patients to seek primary care. The challenges associated with developing effective pain management strategies can be perceived as a burden on the patient-provider relationship.

Objective

This study explored the relationship between patients’ overall satisfaction with their primary care providers (PCPs) and their satisfaction with their chronic pain treatment, as well as the provider behaviors that contributed to chronic pain patients’ satisfaction with their PCPs.

Design

Concurrent nested mixed-methods design

Participants

97 patients with chronic pain who were assigned to the usual care arm of the Pain Program for Active Coping and Training (PPACT) study.

Approach

We analyzed phone interview and survey data (n = 97). Interviews assessed provider behaviors that led to patient satisfaction. Interview transcripts were analyzed based on a content analysis approach. Survey responses assessed patient satisfaction with primary care and pain services. We calculated a Pearson’s correlation coefficient using five response categories.

Key Results

Interviews revealed that high satisfaction with primary care was driven by five concrete PCP behaviors: (1) listening, (2) maintaining communication with patients, (3) acting as an access point to comprehensive pain care, (4) providing an honest assessment of the possibilities of pain care, and (5) taking time during consultations with patients. In surveys, participants reported higher satisfaction with their primary care services than with the pain services they received; these variables were only moderately correlated (r = 0.586).

Conclusions

Results suggest that patients with chronic pain can view the relationship with their PCPs as positive, even in the face of low satisfaction with their pain treatment. The expectations that these patients held of PCPs could be met regardless of providers’ ability to successfully relieve chronic pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 20% of US adults report chronic pain1,2,3,4; it is one of the most frequent reasons patients seek medical care.3, 5 Chronic pain disproportionately impacts women and older adults,2 and most individuals with chronic pain also experience comorbid medical and mental health conditions.6,7,8 Primary care providers (PCPs) deliver the majority of care for chronic pain.9 Unfortunately, accessing effective treatment options for chronic pain can be challenging for many patients. PCPs report feeling inadequately trained to appropriately treat patients with chronic pain,10,11 and conflicts surrounding the prescription of opioids can complicate the patient-provider relationship.12,13,14 Patients with chronic pain report negative experiences establishing credibility with their PCPs, as their conditions are often medically unexplained.15

A positive relationship between patients and their PCPs is fundamental to good patient care, especially for patients with chronic pain.16 The approach PCPs adopt in engaging with patients has been shown to influence health outcomes17 and patients’ beliefs and attitudes about pain.18 Providers’ communication behaviors are an important factor that drives patient satisfaction.19 Specifically, patient satisfaction is associated with trusting one’s PCP, feeling listened to, and being able to communicate with one's PCP in between visits.20

Researching patient-provider communication about chronic pain care is important, yet remains underexplored.21,22 A recent study23 identified strategies PCPs can employ to build trust and develop positive relationships with patients with chronic pain. Patients who had recently visited their PCPs for pain-related concerns appreciated the listening skills of PCPs, found it important to be believed about their pain, and wanted to receive a clear diagnosis. It has also recently been shown that reducing opioids for patients with chronic pain does not negatively affect satisfaction with their PCPs.24 However, most previous studies do not distinguish between patients’ perceptions of their relationship with their PCP and their satisfaction with pain management care, or focus on only one of these areas.25,26,27,28,29 Thus, the degree to which patients’ satisfaction with their providers is driven by their satisfaction with their chronic pain treatment is unknown.

This mixed-methods study assessed patients’ satisfaction with their PCPs and their satisfaction with their chronic pain care treatment, as well as PCP behaviors that patients considered essential to a positive relationship, independent of pain outcomes. By highlighting differences in the satisfaction patients experience in these two domains, this study asks whether it is possible for PCPs to provide satisfactory care to patients with chronic pain in the face of challenges in achieving adequate pain management, and explores the behaviors that could be essential to providing this care.

Analyzing the behaviors primary care physicians can use to provide satisfactory care to patients with chronic pain is crucial, because finding effective chronic pain management strategies will continue to be a challenge. Shifting our attention from providing chronic pain relief to fostering high-quality therapeutic relationships can help address this problem.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

We collected data for this study from January 2016 to March 2017 among a subset of patients with chronic pain assigned to the usual care group of the Pain Program for Active Coping and Training (PPACT) study at Kaiser Permanente Northwest (KPNW). PPACT is an effectiveness-implementation hybrid pragmatic clinical trial conducted within three different KP health care systems: Northwest, Georgia, and Hawaii. Details of the study design have been published previously.30 The study was approved by the KPNW Institutional Review Board. All study procedures followed the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation and the Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association. Patients were eligible for PPACT if they (1) were 18 years or older, (2) were a KP health plan member for at least 180 days, (3) had received long-term opioid treatment (at least two dispensings of long-acting opioids in the past 6 months or at least a cumulative 90-day supply of short-acting opioids during any 4-month period within the past 6 months), (4) had a pain-related diagnosis (as indicated by ICD-9-CM or ICD-10-CM code) within the previous year, and (5) reported a pain interference level of 4 or higher (“On a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 meaning that pain does not interfere and 10 meaning that pain completely interferes, how has pain interfered with your general activity during the past 7 days?”).31,32 Chronicity of pain was not an explicit eligibility criterion; a pain diagnosis and an ongoing prescription of long-term opioid treatment, however, suggested that the pain condition could be chronic. Eligible patients were sent a letter describing the study and invited to participate in an orientation session. Patients attending the session then had the option to enroll in the study. Upon enrollment, but prior to randomization, all study participants responded to a survey by phone which included two items assessing satisfaction with primary health care services and pain services in the prior 3 months on a 5-item Likert scale. These data were collected by trained interviewers.

This analysis reports on a sub-study of PPACT that used a concurrent nested mixed-methods design,33 using quantitative survey data collected as part of the main trial along with qualitative interview data from a subset of participants at the KPNW site. A portion of participants randomized to the usual care group (120) were invited to participate in a one-time telephone interview with study staff. Participants were contacted up to 3 times by telephone to schedule an interview. Ninety-seven participants completed the semi-structured phone interview, which lasted between 20 and 60 min (see online appendix for interview guide). For this study, we analyzed only the survey data of the 97 participants who also completed the interview. Participants were not compensated for their participation in the survey or the interview.

Electronic Health Records Data

Participants agreed to the use of their electronic health records data for the 12 months prior to enrollment. To understand participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics, we assessed the following: age, sex, race, ethnicity, comorbid medical and mental health conditions, number and types of non-malignant chronic pain types, and number of primary care contacts in the past 6 months (Table 1). The ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM codes used to identify non-malignant chronic pain types came from the Pain Condition ICD-9-CM to ICD-10-CM Crosswalk and are available on this publicly accessible GitHub site: https://github.com/PainResearch/PainCondition_ICD9CM_ICD10CM_Crosswalk. More information about the development of these criteria is provided elsewhere.34 Characteristics were selected based on their relevance to the main trial as demographic characteristics and comorbidities of patients with chronic pain.

Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis

We used several strategies to improve the credibility and trustworthiness of our data, including using trained interviewers; a semi-structured interview guide; and a formal, team-based approach to analysis. We validated our findings by comparing results across qualitative and quantitative data sources.

Interviews were conducted by a member of the study team (AF) who has 20 years of experience in qualitative research and mental health counseling. She had no prior relationship with any of the participants and was introduced to participants as a study team member. The goal of the semi-structured interviews was to assess patients’ perspective on the services received for their chronic pain condition, including assessment of provider behaviors that contribute to patient satisfaction (see online appendix for interview guide). The interviews were recorded with participants’ permission.

All interviews were transcribed; transcripts were entered and coded in the NVIVO 10 qualitative data analysis software. Using a content analysis approach, the primary author (IG) developed a code list based on emergent themes that surfaced during transcript review. Qualitative research team members (IG, AF, CKM) each coded three transcripts based on the initial code list, assigning codes to appropriate text segments throughout the transcripts. They then compared and discussed codes and refined each code’s scope and definition to resolve coder disagreements. Additional codes were identified as needed. The coders agreed on four high-level themes (individual, institutional, and relational factors and other) and nine sub-themes that were relevant for understanding patients’ appraisal of pain care. The primary author then coded all 97 interview transcripts. Analyses for this paper focus on the codes for customer service experience and treatment plan, since these codes captured the patients’ impressions of their chronic pain–specific care plans and their satisfaction with the chronic pain care they had received from any provider since being a member of the health plan.

An initial analysis of the qualitative data suggested that the majority of patients were satisfied with the relationship and services they received from their primary care provider, while they were largely unsatisfied with the pain care services received (Fig. 1 shows the data analysis process). We therefore turned to the quantitative data to assess the correlation between these two items (analysis and results below). Upon completion of the quantitative data analysis, we returned to the qualitative data to identify specific provider behaviors that resulted in the positive assessment of the patient-provider relationship by study participants, even considering patients’ comparatively low satisfaction with pain treatment.

Quantitative Measures and Analysis

In the pre-randomization survey, participants were asked “In the past 3 months, how satisfied have you been with your primary care services?” and “In the past 3 months, how satisfied have you been with the pain services you have received?” The questions were measured on a 5-item Likert scale where 1 = Very dissatisfied, 2 = Mildly dissatisfied, 3 = Indifferent, 4 = Mostly satisfied, and 5 = Very satisfied.

To compare patients’ satisfaction with the primary care services and pain services received based on the survey data, we collapsed the item response categories for the two satisfaction items into three groups: dissatisfied, indifferent, or satisfied. We then assessed and compared the proportion of participants with responses in each group for each of the two survey items. To assess the relationship between patients’ satisfaction with primary care services and pain services, we calculated a Pearson’s correlation coefficient using all five response categories. A quantitative data analyst performed these analyses in SAS v9.4.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Most patients interviewed were white females with a mean age of 61.3 years, reflecting the population who generally experience chronic pain and receive long-term opioid therapy. The most frequent pain-related diagnoses were associated with fibromyalgia and/or widespread muscle pain (57.7%); limb or extremity pain, joint pain, and arthritic disorders (54.6%); and back or neck pain (47.4% and 12.4%, respectively). More than half of respondents were diagnosed with two or more types of non-malignant chronic pain. Approximately one-third (30.9%) had a diagnosis of depression and 20.6% experienced anxiety. They were also frequent utilizers of primary care services, with a mean of 6.3 contacts in the 6 months prior to study enrollment.

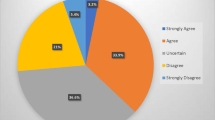

Patient Satisfaction with Care

The quantitative survey data suggested that the majority of patients interviewed were satisfied with their PCP relationship and with the services they received from their PCP (72.2% satisfied; 20.6% dissatisfied). Pain care services received during the same time frame, however, were evaluated as largely unsatisfying: only 50.5% of participants were satisfied with the pain services they received, and 27.8% were dissatisfied (Table 2). Correlation between the two survey items was moderate (r = 0.586).

Positive Provider Behaviors in Chronic Pain Care

During the interviews, about half of respondents spontaneously described their relationship with their PCPs in very positive terms in response to a prompt that inquired about the most helpful services they have received at KP. Analysis of participants’ comments identified five PCP behaviors essential for developing and maintaining positive chronic pain care relationships: (1) listening, (2) maintaining communication with patients, (3) providing access to comprehensive pain care, (4) providing an honest assessment of the possibilities of pain care, and (5) taking time during individual consultations. Each behavior is summarized below, with illustrative quotes presented in Table 3.

-

1.

Listening

Carefully listening to patients’ concerns was considered the foundation of a good patient-provider relationship. If a PCP listened carefully to a patient, patients perceived a willingness to engage with them, to take their concerns seriously, and to appreciate their understanding of their own conditions. Listening was also seen as a necessary first step to addressing a patient’s pain condition.

-

2.

Maintaining communication and responsiveness

Maintaining active lines of communication was important to many patients. Patients were often unsure of what to expect from pain treatment and being able to communicate with their providers about ongoing treatment was helpful. Patients with chronic pain also frequently have long and complicated medical histories. Patients we interviewed reported that they would have to explain their extensive history before being able to receive help from someone other than their PCP. If their PCPs were unavailable or did not respond to messages, they did not feel comfortable seeking care elsewhere. Medication refills were also a sensitive topic, as many patients relied on highly regulated opioid prescriptions for their pain management and thus required ongoing PCP approval for refills. If PCPs and their teams did not respond to patients’ messages promptly, it could leave patients without medication.

-

3.

Providing access to comprehensive pain care

Patients generally recognized that few PCPs have specialized training in pain management and did not expect them to offer comprehensive solutions to their pain conditions. However, they did regard PCPs as experts in navigating pain services and expected them to be familiar with the services offered in the health care system. Patients expected PCPs to inform them about the existing pain treatment infrastructure and to write them referrals for specialist services for pain diagnosis and treatment. Patients reported being frustrated when PCPs relied foremost on offering pain medication as a solution to their pain conditions.

-

4.

Providing an honest assessment of the possibilities of pain care

Few respondents had a treatment plan that provided full relief from pain. While participants appreciated the continuous involvement of PCPs in assessing additional treatment options or services, they also emphasized the importance of PCPs truthfully informing them about the feasibility of identifying and accessing additional treatment options. Assessing the potential of additional pain treatment options was a long and arduous process for many respondents. Although the process created hope of achieving greater relief from their pain conditions, respondents were wary of developing false hope of finding relief from their pain if that was unlikely or impossible.

-

5.

Taking time during individual consultations with patients

Respondents were very appreciative of PCPs who took time to listen to all concerns they wanted to share. Participants were aware of the time limitations imposed on interactions between PCPs and patients and noted that their conditions often required more time than was allotted. If patients were required to return repeatedly for visits within a short time frame, it imposed an additional financial burden due to copay and transportation costs. Respondents therefore placed considerable value on PCPs’ ability to prioritize patients’ needs and concerns over institutional guidelines.

DISCUSSION

Our goal was to contribute to the literature on patient-provider communication in chronic pain care. By concurrently analyzing patients’ satisfaction with their chronic pain treatment and exploring drivers of satisfaction, we illustrate the importance of fostering ongoing patient-provider relationships. Rather than basing their assessment on singular incidents, patients described characteristics that can be fostered over the course of patient-provider relationships as crucial for developing and maintaining satisfaction. Specifically, our study suggests that patients do not base their assessment of their PCPs on their satisfaction with their overall pain treatment: patients’ satisfaction with their primary care services was only moderately correlated with their satisfaction with pain services. In the eyes of patients, the quality of the patient-provider relationship is determined by PCPs exhibiting five core behaviors: (1) listening, (2) maintaining communication with patients, (3) providing access to comprehensive pain care, (4) providing an honest assessment of the possibilities of pain care, and (5) taking time during individual consultations.

Our results resonate with existing research that emphasizes the importance of building provider-patient relationships that move beyond biomedical approaches when treating chronic pain.27,35 Other studies among patients with chronic conditions such as obesity or mental health problems have also emphasized the importance of provider listening and taking time in influencing patients’ satisfaction.36,37 However, patients with different chronic conditions may value different behaviors in primary care providers.38 To our knowledge, the emphasis that patients in this study placed on an honest assessment of the possibilities of pain care to address their pain has not previously been reported.

Research on conversations about opioid tapering between primary care providers and patients highlights the importance of reassuring patients of ongoing support for their pain treatment and exploring alternative treatment options together.39,40,41 Our research points to the potential these conversations hold for fostering stronger patient-provider relationships. By engaging patients in forthright conversations about the availability and accessibility of existing pain management strategies and programs, providers can demonstrate their ongoing involvement in patients’ chronic pain care. This is also an opportunity for providers to encourage patients to engage in non-pharmacological therapies for pain management, which can serve to clarify expectations for treatment plans and encourage patients to take an active role in managing their own pain. While these conversations might appear challenging, our research illustrates that patients do not base their satisfaction with their providers on singular interactions but recognize the value and importance of an ongoing relationship.

Our results are consistent with other studies finding that patients with chronic pain perceive listening as a crucial behavior in driving treatment satisfaction,20,23 and with a large body of work linking effective patient-provider communication to improved satisfaction and clinical outcomes.42 Patients in this study also explicitly requested that providers take extra time during encounters. Carefully listening to patients and maintaining an active line of communication with them ultimately also require providers to be able to devote time to individual patients. Time constraints, however, pose a challenge in primary care—especially for patients with chronic conditions.43,44 Novel institutional approaches are needed to allow providers to spend more time on patients with chronic pain.

Our results suggest that patients appreciate their PCPs not just as generalists but also as care coordinators. Although primary care is an appropriate facilitator for chronic illness management,45,46 providing this facilitation requires PCPs to take additional time and to maintain awareness of the range of services available to patients with chronic pain. In addition to familiarity with health care systems, there are also health plan and insurance limitations that affect the ability of PCPs to refer patients to specialist services. Care coordinators or case managers could help patients navigate health care systems. Addressing these barriers could make it easier for PCPs to facilitate chronic pain care, improving outcomes for this population and reducing long-term health care utilization.

Our study has some limitations. Data were collected in one delivery system only (KPNW), which limited the diversity of the population for inclusion in our study and resulted in a group of participants who were mostly white (92%). Both the limited racial/ethnic diversity in the sample and the fact that all patients and providers were operating within the same health system may limit generalizability of our results to other populations. Future research should explore whether the relationship we observed differs by certain patient characteristics, such as gender and race. The patients were all opioid users, which does not represent the entire spectrum of patients with chronic pain. At the same time, opioid users are an important group of patients with chronic pain. The recent emphasis on tapering opioids has raised questions about treatment satisfaction and the role the continued prescribing of opioids plays in maintaining satisfactory patient-provider relationships.41 The large sample size in this study (n = 97) is an additional strength. The interviews were presented as an opportunity for patients assigned to usual care to provide expert feedback about their chronic pain care. During these interviews, patients were asked to base their assessment of their pain care not on a specific patient-provider interaction, but on their overall experiences receiving pain care within the health care system. Finally, randomization took place after participants completed the survey, so assignment to the usual care group could not have affected participants’ satisfaction ratings with their primary and pain care services.

CONCLUSION

Caring for patients with chronic pain requires navigating complex interpersonal relationships. This study demonstrates that patients with chronic pain can be generally satisfied with their PCPs, even when they are dissatisfied with their chronic pain care. This study also illustrates the importance of establishing ongoing relationships between patients with chronic pain and PCPs and provides concrete suggestions for building successful relationships. To support this, institutions must address the barriers providers face in providing adequate time and support to these patients.

References

Pitcher MH, Von Korff M, Bushnell MC, Porter L. Prevalence and profile of high-impact chronic pain in the United States. J Pain. 2019; 20(2):146–160.

Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain among adults - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(36):1001–1006.

Institute of Medicine Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care and Education. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) National Academy of Sciences; 2011.

Johannes CB, Le TK, Zhou X, Johnston JA, Dworkin RH. The prevalence of chronic pain in United States adults: results of an Internet-based survey. J Pain. 2010;11(11):1230–1239.

Jonsdottir T, Jonsdottir H, Lindal E, Oskarsson GK, Gunnarsdottir S. Predictors for chronic pain-related health care utilization: a cross-sectional nationwide study in Iceland. Health Expectations. 2015;18(6):2704–2719.

Butchart A, Kerr EA, Heisler M, Piette JD, Krein SL. Experience and management of chronic pain among patients with other complex chronic conditions. Clin J Pain. 2009;25(4):293–298.

Dominick CH, Blyth FM, Nicholas MK. Unpacking the burden: understanding the relationships between chronic pain and comorbidity in the general population. Pain. 2012;153(2):293–304.

van Hecke O, Torrance N, Smith BH. Chronic pain epidemiology and its clinical relevance. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111(1):13–18.

Andersson HI, Ejlertsson G, Leden I, Schersten B. Impact of chronic pain on health care seeking, self care, and medication. Results from a population-based Swedish study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53(8):503–509.

Lin JJ, Alfandre D, Moore C. Physician attitudes toward opioid prescribing for patients with persistent noncancer pain. Clin J Pain. 2007;23(9):799–803.

Upshur CC, Luckmann RS, Savageau JA. Primary care provider concerns about management of chronic pain in community clinic populations. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):652–655.

Bendtsen P, Hensing G, Ebeling C, Schedin A. What are the qualities of dilemmas experienced when prescribing opioids in general practice? Pain. 1999;82(1):89–96.

Matthias MS, Parpart AL, Nyland KA, et al. The patient-provider relationship in chronic pain care: providers’ perspectives. Pain Med. 2010;11(11):1688–1697.

Spitz A, Moore AA, Papaleontiou M, Granieri E, Turner BJ, Reid MC. Primary care providers’ perspective on prescribing opioids to older adults with chronic non-cancer pain: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11:35.

Werner A, Malterud K. It is hard work behaving as a credible patient: encounters between women with chronic pain and their doctors. Soc Sci Med 2003;57(8):1409–1419.

Brown JB, Moira S; Bridget R. Outcomes of patient-provider interaction. In: Thompson TLD, Alicia M, Miller KI, Parrott R, eds. Handbook of Health Communication. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003:141–161.

Michie S, Miles J, Weinman J. Patient-centredness in chronic illness: what is it and does it matter? Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51(3):197–206.

Darlow B, Dowell A, Baxter GD, Mathieson F, Perry M, Dean S. The enduring impact of what clinicians say to people with low back pain. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(6):527–534.

Clever SL, Jin L, Levinson W, Meltzer DO. Does doctor-patient communication affect patient satisfaction with hospital care? Results of an analysis with a novel instrumental variable. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(5 Pt 1):1505–1519.

Upshur CC, Bacigalupe G, Luckmann R. “They don’t want anything to do with you”: patient views of primary care management of chronic pain. Pain Med. 2010;11(12):1791–1798.

Henry SG, Matthias MS. Patient-clinician communication about pain: a conceptual model and narrative review. Pain Med. 2018;19(11):2154–2165.

Matthias MS, Bair MJ. The patient-provider relationship in chronic pain management: where do we go from here? Pain Med. 2010;11(12):1747–1749.

Evers S, Hsu C, Sherman KJ, et al. Patient perspectives on communication with primary care physicians about chronic low back pain. Perm J. 2017;21:16–177.

Sharp AL, Shen E, Wu Y-L, et al. Satisfaction with care after reducing opioids for chronic pain. Am J Manag Care. 2018; 24(6):e196-e199.

Hirsh AT, Atchison JW, Berger JJ, et al. Patient satisfaction with treatment for chronic pain: predictors and relationship to compliance. Clin J Pain. 2005;21(4):302–310.

Jonsdottir T, Gunnarsdottir S, Oskarsson GK, Jonsdottir H. Patients’ perception of chronic-pain-related patient-provider communication in relation to sociodemographic and pain-related variables: a cross-sectional nationwide study. Pain Manag Nurs. 2016;17(5):322–332.

Kirby K, Dunwoody L, Millar R. What type of service provision do patients with chronic pain want from primary care providers? Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(18):1514–1519.

McCracken LM, Klock PA, Mingay DJ, Asbury JK, Sinclair DM. Assessment of satisfaction with treatment for chronic pain. J Pain Symptom Manag. 1997;14(5):292–299.

Robinson ME, Brown JL, George SZ, et al. Multidimensional success criteria and expectations for treatment of chronic pain: the patient perspective. Pain Med. 2005;6(5):336–345.

DeBar L, Benes L, Bonifay A, et al. Interdisciplinary team-based care for patients with chronic pain on long-term opioid treatment in primary care (PPACT) – protocol for a pragmatic cluster randomized trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;67:91–99.

Krebs EE, Lorenz KA, Bair MJ, et al. Development and initial validation of the PEG, a three-item scale assessing pain intensity and interference. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(6):733–738.

Krebs EE, Bair MJ, Damush TM, Tu W, Wu J, Kroenke K. Comparative responsiveness of pain outcome measures among primary care patients with musculoskeletal pain. Med Care. 2010;48(11):1007–1014.

Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL, Gutman ML, Hanson WE. An Expanded Typology for Classifying Mixed Methods Research Into Designs. In: Tashakkori ATC, ed. Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003:209–240.

Mayhew M, DeBar LL, Deyo RA, et al. Development and assessment of a crosswalk between ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM to identify patients with common pain conditions. J Pain. 2019

Sheridan NF, Kenealy TW, Kidd JD, et al. Patients’ engagement in primary care: powerlessness and compounding jeopardy. A qualitative study. Health Expect. 2015;18(1):32–43.

Campbell SM, Gately C, Gask L. Identifying the patient perspective of the quality of mental healthcare for common chronic problems: a qualitative study. Chronic Illn. 2007;3(1):46–65.

Pollak KI, Alexander SC, Tulsky JA, et al. Physician empathy and listening: associations with patient satisfaction and autonomy. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(6):665–672.

Groenewoud S, Van Exel NJ, Bobinac A, Berg M, Huijsman R, Stolk EA. What influences patients’ decisions when choosing a health care provider? Measuring preferences of patients with knee arthrosis, chronic depression, or Alzheimer’s disease, using discrete choice experiments. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(6):1941–1972.

Frank JW, Levy C, Matlock DD, et al. Patients’ perspectives on tapering of chronic opioid therapy: a qualitative study. Pain Med. 2016;17(10):1838–1847.

Matthias MS, Krebs EE, Bergman AA, Coffing JM, Bair MJ. Communicating about opioids for chronic pain: a qualitative study of patient attributions and the influence of the patient-physician relationship. Eur J Pain. 2014;18(6):835–843.

Matthias MS, Johnson NL, Shields CG, et al. “I’m not gonna pull the rug out from under you”: Patient-provider communication about opioid tapering. J Pain. 2017;18(11):1365–1373.

Beck RS, Daughtridge R, Sloane PD. Physician-patient communication in the primary care office: a systematic review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15(1):25–38.

Konrad TR, Link CL, Shackelton RJ, et al. It’s about time: physicians’ perceptions of time constraints in primary care medical practice in three national healthcare systems. Med Care. 2010;48(2):95–100.

Østbye T, Yarnall KSH, Krause KM, Pollak KI, Gradison M, Michener JL. Is there time for management of patients with chronic diseases in primary care? Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(3):209–214.

Rothman A, Wagner EH. Chronic illness management: what is the role of primary care? Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):256–261.

Seal K, Becker W, Tighe J, Li Y, Rife T. Managing chronic pain in primary care: it really does take a village. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(8):931–934.

Funding

The PPACT study is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Common Fund, through a cooperative agreement (UH2AT007788, UH3NS088731) from the Office of Strategic Coordination within the Office of the NIH Director.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The study was approved by the KPNW Institutional Review Board. All study procedures followed the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation and the Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The views presented here are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 15 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gruß, I., Firemark, A., McMullen, C.K. et al. Satisfaction with Primary Care Providers and Health Care Services Among Patients with Chronic Pain: a Mixed-Methods Study. J GEN INTERN MED 35, 190–197 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05339-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05339-2