Abstract

Purpose

The use of interventional pain management (IPM) modalities to alleviate chronic pain is increasing despite the lack of high-quality evidence. We undertook this survey to explore patterns, training, and attributes of IPM practice.

Methods

We administered a 32-item survey via seven Canadian physician member organizations, whose members were engaged in the management of chronic pain.

Results

Of 777 physicians contacted, 256 (33%) responded: 45 (6%) declined to participate and 211 (27%) agreed to participate; the number of participants answering any given question varied. One hundred and sixty-nine of 194 (87%) practiced IPM and 103 of 194 (53%) managed only non-cancer pain. Pain management training of ≥ six months was associated with higher odds of IPM training (odds ratio [OR], 2.98; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.32 to 6.7), but not necessarily ongoing IPM practice (OR, 1.97; 95% CI, 0.74 to 5.3). A substantial percentage of physicians (108 of 168 [64%]) practiced IPM based only on training received during either their base residency program or courses. Only 48 of 186 (26%) felt that there were adequate opportunities for IPM training, and 69 of 186 (37%) believed that their colleagues practiced IPM in accordance with the best current evidence.

Conclusions

Our survey indicates that IPM practice and training were not uniform, and that interventional therapies for chronic pain may not be performed in accordance with the best available evidence. Our survey highlights a lack of IPM training opportunities, which may result in substandard training. Concerted efforts involving physician organizations and regulators are needed to standardize IPM training and develop clinical guidelines to optimize evidence-based practice.

Résumé

Objectif

L’utilisation de modalités de prise en charge interventionnelle de la douleur pour soulager la douleur chronique est en augmentation et ce, malgré l’absence de données probantes de qualité élevée. Nous avons réalisé ce sondage afin d’explorer les modèles, la formation et les attributs des pratiques de prise en charge interventionnelle de la douleur.

Méthode

Nous avons administré un sondage comportant 32 items par le biais de sept organismes de médecins au Canada dont les membres étaient impliqués dans la prise en charge de la douleur chronique.

Résultats

Parmi les 777 médecins contactés, 256 (33 %) ont répondu : 45 (6 %) ont refusé de participer et 211 (27 %) ont accepté; le nombre de répondants variait d’une question à l’autre. Parmi les répondants, 169/194 (87 %) pratiquaient une prise en charge interventionnelle de la douleur et 103/194 (53 %) ne prenaient en charge que la douleur non cancéreuse. Une formation en prise en charge de la douleur d’au moins six mois était associée à une plus grande probabilité de formation en prise en charge interventionnelle de la douleur (rapport de cotes [RC], 2,98; intervalle de confiance [IC] 95 %, 1,32 à 6,7), mais pas nécessairement à une pratique de prise en charge interventionnelle de la douleur (RC, 1,97; IC 95 %, 0,74 à 5,3). Un pourcentage considérable de médecins (108/168 [64 %]) pratiquaient une prise en charge interventionnelle de la douleur en se fondant exclusivement sur la formation reçue pendant leur programme de résidence de base ou durant des cours. Seuls 48/186 (26 %) étaient d’avis que les occasions de formation en prise en charge interventionnelle de la douleur étaient adéquates, et 69/186 (37 %) pensaient que leurs collègues pratiquaient ce type de prise en charge selon les meilleures données probantes actuelles.

Conclusion

Notre sondage indique que la pratique et la formation en prise en charge interventionnelle de la douleur ne sont pas uniformes, et que les thérapies interventionnelles pour la douleur chronique pourraient ne pas être réalisées selon les meilleures données probantes disponibles. Notre sondage met en lumière l’absence d’occasions de formation en prise en charge interventionnelle de la douleur, ce qui pourrait avoir pour résultat une formation sous-optimale. Des efforts concertés de la part des organismes de médecins et de régulation sont nécessaires afin de standardiser la formation et de mettre au point des directives cliniques qui optimiseront la pratique fondée sur des données probantes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Chronic pain is a major health problem associated with considerable socioeconomic burden.1 A 2010 Canadian report estimates direct healthcare costs at $6 billion per year and productivity costs (job loss and sick days) at another $37 billion per year.2 Interventional pain management (IPM) refers to the use of percutaneous interventions to block or modify pain signals.3 These precise, target-specific interventions are done with the objectives of diagnosis and/or treatment. IPM modalities can decrease chronic pain intensity and complement ongoing pharmacologic, psychologic, and physical therapy approaches. Broadly, IPM modalities include peripheral nerve blocks, neuraxial injections, radiofrequency treatments, and neuromodulation. The role of interventional therapy is to decrease pain and facilitate functional restoration.4,5

Many aspects of IPM are not clearly defined, including definitive indications, timing, frequency, and provider expertise. Some consider the use of IPM to be controversial. A 2009 guideline sponsored by the American Pain Society (APS) found insufficient evidence to make recommendations for most interventional procedures.6 Nevertheless, the American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians published a guideline recommending most interventional therapies,7 and questioned the discrepant studies cited in the guidelines by the APS.8 There is a perception that results of published trials and reviews are influenced by specialty and those done by interventional physicians more likely to yield positive findings.9 Unlike medications, interventions are billed as physician-performed procedures and it is perceived that there is a financial incentive to perform IPM.10,11 These observations have led to a lack of credibility.12 In 2018, the UK National Health Services proposed to defund injections for non-specific low back pain without sciatica, based on lack of evidence.13 Despite limited evidence of effectiveness, data from Health Quality Ontario (HQO) using Ontario Health Insurance Plan billing data indicate that the use of some IPM procedures has more than doubled from 2011 to 2015, primarily through an increase in the number of procedures performed per patient.14

Currently, there are no standards for IPM training and practice in Canada.15 Although traditionally associated with anesthesia, physicians from other specialties such as radiology and physical medicine and rehabilitation also practice IPM. Unfortunately, pain training during medical school or residency programs is inadequate.16,17,18,19 To help address this shortcoming, pain fellowship programs were developed and are currently offered by several university departments of anesthesia (https://www.cas.ca/English/ACUDA-Fellowships). Nevertheless, the curriculum and the training within these programs are varied, and do not necessarily include IPM techniques.

Across all disciplines, lack of training has been identified as a barrier to implementing evidence-based guidelines into clinical practice,20 and this lack may promote the misuse of medical interventions21 and exposure to potential complications.22 Recognizing the need to standardize training and regulate practice, the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario (CPSO) published a change of scope policy in 2016 requiring specific training and procedural-specific knowledge, skills, and judgement for the practice of IPM.23 We conducted a survey of Canadian physicians attending to chronic pain patients to explore practice patterns, training, and attributes of IPM practice. We also sought to explore the association between “training modality” with “IPM training” and “present IPM practice”.

Methods

Questionnaire development

We developed a 32-item questionnaire to explore the training, practice pattern, and approach of Canadian pain physicians regarding IPM (eAppendix, available as Electronic Supplementary Material). The Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board approved our survey for dissemination (project # 2016-1717, 4 November 2016). We used the definition of IPM in the CPSO Change of Scope Policy and Document (for physicians who have changed, or plan to change their scope of practice to include interventional pain management): “the diagnosis and treatment of pain involving the percutaneous introduction of medications into the body at sites involved in the production and/or modulation of pain”.23 The survey was developed by the author team consisting of IPM practitioners and epidemiologists.

We pre-tested the survey with five physicians practicing IPM to acquire their feedback on clarity and comprehensiveness, and their suggestions were incorporated into the final version. All five physicians practiced at a teaching institute; three had more than five years of experience and two had recently completed their training. The finalized survey and its responses were translated into French by an investigator whose primary language was French (E.B-C.). The questionnaire was organized in two parts with the first part evaluating chronic pain practice and training, and the second part specific to interventional pain practice. Response options were either multiple choice questions or a five-point Likert scale, as open-ended questions have a higher rate of missing data.24

Questionnaire distribution

We used the online tool Survey Monkey (https://www.surveymonkey.com/; SurveyMonkey Canada Inc., Ottawa, ON, Canada) to administer our survey. We approached seven Canadian organizations, representing 777 physicians, who sent their members an email request with a link to complete our survey between November 1 2016 and April 30 2017: Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society Chronic Pain section (n = 107); Canadian Association of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (n = 228); Canadian Interventional Radiology Association (n = 140); World Institute of Pain-Canada chapter (n = 20); Canadian Academy of Pain Management (n = 182); Quebec Pain Society (n = 37); and Pain Medicine Physicians of British Columbia Society (n = 63). A reminder email was sent two months after the initial request to encourage participation. Physicians with an active chronic pain practice or physicians who were engaged in performing pain interventions without their own active pain practice (such as interventional radiologists who perform interventions only upon referral)25 were eligible to complete the survey.

Statistical analysis

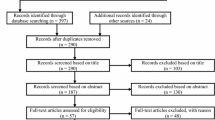

Physician characteristics, experience with IPM, and practice settings are presented using counts and percentages, and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). The limits of precision were estimated using Wald confidence limits, which is the default CI produced for SURVEYFREQ procedure in the Statistical Analysis Software (SAS). Responses for opportunities for IPM training in Canada and the use of evidence-based IPM practices are summarized using pie charts. We used multivariable logistic regression to explore the association between modality of training (pain fellowship vs others), and training duration (≥ six vs < six months) for the individual outcomes of: 1) IPM training and 2) IPM practice. We hypothesized that physicians who completed a pain fellowship, or had ≥ six months training in pain medicine would be more likely to receive IPM training, and also practice IPM. For the above variables, we checked for multicollinearity using variance inflation factors. Measures of association were reported as odds ratios (ORs) and associated 95% CI. We considered that we would need at least ten completed surveys that endorsed the least common outcome category for each dependent variable category to ensure that our regression models were not overfitted. All comparisons were two-tailed, and we set our level of significance at P < 0.05. We performed all analyses using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The survey was sent to 777 physicians. Responses were received from 256 individuals (33%): 45 declined participation (reasons: no active chronic pain practice, does not perform IPM, did not want to take part in the survey), while 211 of 732 agreed to participate (179 responses in English; 32 in French; participation rate of 27% of those surveyed). The number of participants answering each question varied. Most respondents were between the ages of 30-60 yr (87%), specialized in anesthesia (51%), and were male (76%) (Table 1). Respondents were evenly split between managing only chronic non-cancer pain (53%) and both cancer and non-cancer chronic pain (46%). Only about 13% worked in pain medicine full time, with the majority (58%) providing this service between two to four days per week. Nearly two-thirds (64%) worked in an interdisciplinary practice and slightly more than half (56%) had been in practice more than ten years. IPM was provided by a majority (87%) of physicians (Table 2). Opinion was divided as to whether physicians practice evidence-based IPM (3% strongly agreed, 34% agreed, 68% uncertain; Fig. 1).

The nature of training in pain management was evenly divided: part of primary residency program (35%), formal fellowship (34%), or clinical experience, observation, and/or courses (31%, Table 3). A majority (77%) reported training that included instruction in IPM techniques. Most (approximately 70%) were trained in Canada, and the duration of training was variable, with a slight majority (approximately 30%) reporting six to 12 months. Only 26% indicated that there were adequate IPM training opportunities available in Canada, 30% were uncertain, with the remaining 44% indicating an inadequate situation (Fig. 2). For the variables of “training modality” and “training duration” used in our multivariable regression model, the variance inflation factors were very low (< 1.2), indicating very low multicollinearity. Training of ≥ six months in pain medicine was associated with IPM training (OR, 2.98; 95% CI, 1.32 to 6.73; P = 0.009), but not necessarily with ongoing IPM practice (OR, 1.97; 95% CI, 0.74 to 5.26). There was no association of pain fellowship with IPM training (OR, 1.96; 95% CI, 0.75 to 5.15) or ongoing IPM practice (OR, 3.00; 95% CI, 0.79 to 11.41), but we acknowledge that we likely had an insufficient number of respondents to reliably assess these associations.

Approaches to IPM

Among 194 physicians, 87% reported on their practice of IPM. Most (75%) treated a mix of patients with spinal and non-spinal pain and relatively few (8%) only performed interventions on a consult basis as requested by another physician (Table 4). About half (48%) were engaged in training other physicians (residents or fellows). A majority (73%) reported using image guidance for IPM interventions.

For safety and technical reasons, spinal injections are suggested to be performed using fluoroscopy or computed tomography imaging.26 Although most (90%) physicians performed one or more spinal interventions, only 52% performed these procedures with image guidance (Table 5). The types of the spinal and non-spinal IPM procedures performed by our respondents are shown in Table 5. In descending order of frequency, the five most common spinal interventions were: 1) sacro-iliac joint injections (92%), 2) epidural injections (79%), 3) facet joint injections or medial branch blocks (73%), 4) paravertebral nerve blocks (61%), and 5) nerve root injections (56%). In descending order of frequency, the five of the common indications for procedures performed using ultrasound guidance were: 1) peripheral nerve blocks (78%), 2) piriformis muscle injections (60%), 3) soft tissue injections (58%), 4) major joint injections (50%), and 5) stellate ganglion injections (50%). Among procedures performed under ultrasound, 43% reported using it for trigger point injections (Table 5).

Discussion

Almost 90% of Canadian pain physicians who responded to our survey are engaged in IPM with 77% reporting to have had specific training in IPM. Pain management training of ≥ six months was associated with higher odds of IPM training. Approximately one-half of respondents performed spinal interventions without imaging guidance. Less than one-half had opportunities to supervise trainees. Only about one-third opined that their colleagues practiced IPM in accordance with current evidence, and about three-quarters felt that there were inadequate opportunities for IPM training in Canada.

About one-third of our respondents had pain fellowship (34%) training, while another third (35%) obtained their pain medicine training as part of their base residency, with the rest having their training only by clinical experience, observation, and/or courses. This observation is different compared with a 2005 survey in which in 42% had fellowship training and 58% were trained by observation.27 We would argue that pain medicine training during a base residency program is inadequate because it is limited in duration and scope.19 As such, it is unfortunate that the anesthesia-based pain fellowship programs in Canada have decreased in number from 16 in 2004 to eight in 2018.17,28 The recently initiated residency in pain medicine by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC) allows physicians from 11 different specialties to complete a two-year program. Presently, this is offered in eight institutions (total 12 positions) across Canada. Although the RCPSC specialty committee in pain medicine unanimously endorsed family medicine training as an eligible entry route, this was not endorsed by the College of Family Physicians of Canada.17 This is unfortunate given that a substantial number of family physicians become involved in managing chronic pain and, ideally, should receive appropriate training. Of note, there are no specific recommendations for IPM training and standards within the RCPSC pain medicine residency program. IPM necessitates careful patient selection and the safe performance of procedures in an appropriate setting.15,29 Lack of training standards leads to variation in physician skill sets and competence.21 Recognizing the need for regulations, the CPSO and College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia have proposed standards and competencies for physicians changing their scope of practice to include IPM procedures.23,30 As a long-term proposal, the CPSO also intends to promote competency as defined by the RCPSC Specialty Committee on Pain Medicine.23 Nevertheless, for the moment, this expectation does not seem to be within the scope of RCPSC pain medicine residency. In any event, given the limited opportunities that exist for IPM training in Canada, it remains to be seen how physicians can effectively fulfil the minimum CPSO standards, which includes 900 hr of training including supervision, and achieve sufficient procedural competency.

There is a lack of consensus regarding the effectiveness of IPM therapies for chronic pain.5,6,7,21,31 Although other modalities to treat chronic pain (e.g., medication32,33,34 and physical activity),35 may also be of questionable benefit, IPM faces a particular challenge because of the potential for its misuse, as suggested by the recent large-scale increases in IPM procedures.13,36,37 Within Canada, data from HQO indicate that bursa and joint injections and scapular nerve blocks doubled between 2011 and 2015, primarily driven by the increase in number of procedures per patient.14 This has led to calls for greater regulation and reconsideration of remuneration for repeated interventional procedures, particularly in the face of questionable clinical benefit.12,13

In our survey, 64% of IPM physicians function as part of a multidisciplinary team. Multidisciplinary treatment is defined as multimodal (concurrent use of separate therapeutic interventions) treatment provided by practitioners from different disciplines.38 With regards to chronic pain management, this typically includes a psychologist and physical rehabilitation health-worker, in addition to the primary treating physician. Chronic pain may evoke both behavioural and physical maladaptation to the pain and suffering, and psychological and functional recovery is best achieved in a multidisciplinary setting. There is strong evidence in favour of a multidisciplinary approach compared with standard medical treatment for chronic pain.39 Of note, some payors only support for IPM in the context of multidisciplinary care.40 Access to multidisciplinary care for chronic pain is limited in Canada and other countries. A study published in 2007 identified 120 multidisciplinary clinics in Canada of which 72 were publicly funded with the remainder funded by other sources included compensating agencies, insurance companies, or patients.41 Another survey in the province of Quebec showed that 26% of their anesthesia-based pain clinics offered a multidisciplinary approach.42 In the UK National Pain Audit (2010-2012), 40% of pain clinics (81 out of 204) in England were reported to meet the minimum standards for a multidisciplinary pain clinic.43

In our survey, epidural injections and sacro-iliac joint and facet joint procedures were the most commonly performed procedures. In the USA, facet joint and sacro-iliac joint interventions increased by 313% between 2000 and 2014,44 and epidural injections increased by 271% between 1994 and 2001.45 In > 50% of these epidural injections, the clinical indications did not include sciatica or radicular pain that best respond to these interventions.44,45 The figures from 2014-2015 UK Hospital Episodes Statistics data also suggest similar increases over time with these procedures.37

To accurately assess the current situation in Canada, we contacted pain physicians with varied training backgrounds via seven Canadian physician organizations, and we distributed the survey in English and French. Our survey had a participation rate of 27%, which is similar to other physician surveys,46,47 and surveys of similar cohorts in other countries.48,49 Nevertheless, we acknowledge that our data may still not accurately reflect the Canadian perspective regarding physicians practicing IPM. We also acknowledge that all surveyed material regarding opinion and impression are individual observations that may not accurately reflect the true situation.

To conclude, our survey indicates that in Canada there is considerable variability in both pain training and practice. A substantial proportion of physicians practice IPM without formal training and there is an urgent need to establish minimum standards of training and performance. High-quality, well-designed studies are required to help inform, develop, and evolve clinical guidelines such that IPM becomes, and remains, evidence-based.

References

Phillips C, Main C, Buck R, Aylward M, Wynne-Jones G, Farr A. Prioritising pain in policy making: the need for a whole systems perspective. Health Policy 2008; 88: 166-75.

Lynch ME. The need for a Canadian pain strategy. Pain Res Manag 2011; 16: 77-80.

Manchikanti L, Boswell MV, Raj PP, Racz GB. Evolution of interventional pain management. Pain Physician 2003; 6: 485-94.

Gatchel RJ, Peng YB, Peters ML, Fuchs PN, Turk DC. The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: scientific advances and future directions. Psychol Bull 2007; 133: 581-624.

Roth RS, Geisser ME, Williams DA. Interventional pain medicine: retreat from the biopsychosocial model of pain. Transl Behav Med 2012; 2: 106-16.

Chou R, Loeser JD, Owens DK, et al. Interventional therapies, surgery, and interdisciplinary rehabilitation for low back pain: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society. Spine 2009; 34: 1066-77.

Manchikanti L, Boswell MV, Singh V, et al. Comprehensive evidence-based guidelines for interventional techniques in the management of chronic spinal pain. Pain Physician 2009; 12: 699-802.

Datta S, Manchikanti L. Re: Chou R, Loeser JD, Owens DK, et al. Interventional therapies, surgery, and interdisciplinary rehabilitation for low back pain: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society. Spine 2009; 34: 1066-77. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010; 35: 1826; author reply 1826-7.

Cohen SP, Bicket MC, Jamison D, Wilkinson I, Rathmell JP. Epidural steroids: a comprehensive, evidence-based review. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2013; 38: 175-200.

Schofferman J. Interventional pain medicine: financial success and ethical practice: an oxymoron? Pain Med 2006; 7: 457-60.

Richeimer SH. Are we lemmings going off a cliff? The case against the “interventional” pain medicine label. Pain Med 2010; 11: 3-5.

Cohen SP, Deyo RA. A call to arms: the credibility gap in interventional pain medicine and recommendations for future research. Pain Med 2013; 14: 1280-3.

Iacobucci G. NHS proposes to stop funding 17 “unnecessary” procedures. BMJ 2018; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2903.

Health Quality Ontario (HQO). Utilization of Interventional Techniques in Ontario: OHIP Physician Claims Analysis - 2018. (These data are being prepared for publication and are presently available by request from the HQO Quality Standards Data Team).

Rathmell JP, Carr DB. The scientific method, evidence-based medicine, and rational use of interventional pain treatments. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2003; 28: 498-501.

Gallagher RM. Pain education and training: progress or paralysis? Pain Med 2002; 3: 196-7.

Morley-Forster P, Karpinski J. Pain medicine–a new credential in Canada. Pain Med 2015; 16: 1038-44.

O’Rorke JE, Chen I, Genao I, Panda M, Cykert S. Physicians’ comfort in caring for patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. Am J Med Sci 2007; 333: 93-100.

Shipton EE, Bate F, Garrick R, Steketee C, Shipton EA, Visser EJ. Systematic review of pain medicine content, teaching, and assessment in medical school curricula internationally. Pain Ther 2018; 7: 139-61.

Fischer F, Lange K, Klose K, Greiner W, Kraemer A. Barriers and strategies in guideline implementation-a scoping review. Healthcare (Basel) 2016; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4030036.

Merrill DG. Hoffman’s glasses: evidence-based medicine and the search for quality in the literature of interventional pain medicine. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2003; 28: 547-60.

Weidner J. Public health says patients of Kitchener clinic at risk of bacterial infection. The Record - 2018. Available from URL: https://www.therecord.com/news-story/8806394-publichealth-says-patients-of-kitchener-clinic-at-risk-of-bacterial-infection/ (accessed October 2019).

The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario. Change of Scope Application: Interventional Pain Management. Available from URL: https://www.cpso.on.ca/CPSO/media/Documents/physician/polices-and-guidance/policies/interventional-pain-management-application.pdf (accessed October 2019).

Griffith LE, Cook DJ, Guyatt GH, Charles CA. Comparison of open and closed questionnaire formats in obtaining demographic information from Canadian general internists. J Clin Epidemiol 1999; 52: 997-1005.

Dixon RG, Khiatani V, Statler JD, et al. Society of interventional radiology: occupational back and neck pain and the interventional radiologist. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2017; 28: 195-9.

Filippiadis DK, Rodt T, Kitsou MC, et al. Epidural interlaminar injections in severe degenerative lumbar spine: fluoroscopy should not be a luxury. J Neurointerv Surg 2018; 10: 592-5.

Peng PW, Castano ED. Survey of chronic pain practice by anesthesiologists in Canada. Can J Anesth 2005; 52: 383-9.

Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society; Association of Canadian University Departments of Anesthesia (CAS-ACUDA). Canadian Postgraduate Fellowship Programs in Anesthesia, Pain and Perioperative Medicine. Available from URL: https://www.cas.ca/en/about-cas/affiliates/acuda/acuda-fellowships (accessed October 2019).

Rathmell JP, Benzon HT, Dreyfuss P, et al. Safeguards to prevent neurologic complications after epidural steroid injections: consensus opinions from a multidisciplinary working group and national organizations. Anesthesiology 2015; 122: 974-84.

College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia. Defining standards for interventional pain management and accrediting facilities. Available from URL: https://www.cpsbc.ca/for-physicians/college-connector/2016-V04-01/05 (accessed October 2019).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK). Low Back Pain and Sciatica in Over 16s: Assessment and Management. National Guideline Center (UK). London: NICE, 2016. Available from URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK401577/ (accessed October 2019).

Deyo RA, Von Korff M, Duhrkoop D. Opioids for low back pain. BMJ 2015; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g6380.

Enke O, New HA, New CH, et al. Anticonvulsants in the treatment of low back pain and lumbar radicular pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2018; 190: E786-93.

Shanthanna H, Gilron I, Rajarathinam M, et al. Benefits and safety of gabapentinoids in chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS Med 2017; 14: e1002369.

Geneen LJ, Moore RA, Clarke C, Martin D, Colvin LA, Smith BH. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 4: CD011279.

Manchikanti L, Singh V, Pampati V, Smith HS, Hirsch JA. Analysis of growth of interventional techniques in managing chronic pain in the Medicare population: a 10-year evaluation from 1997 to 2006. Pain Physician 2009; 12: 9-34.

Poply K, Mehta V. The dilemma of interventional pain trials: thinking beyond the box. Br J Anaesth 2017; 119: 718-9.

International Association for the Study of Pain. Task Force on Multimodal Pain Treatment Defines Terms for Chronic Pain Care - 2017. Available from URL: https://www.iasp-pain.org/PublicationsNews/NewsDetail.aspx?ItemNumber=6981 (accessed October 2019).

Scascighini L, Toma V, Dober-Spielmann S, Sprott H. Multidisciplinary treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review of interventions and outcomes. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008; 47: 670-8.

Accident Compensation Corporation N. Pain Management Services, Guidelines for Providers - 2018. Available from URL: https://www.acc.co.nz/assets/contracts/7bec13b329/pain-management-og.pdf (accessed October 2019).

Peng P, Choiniere M, Dion D, et al. Challenges in accessing multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities in Canada. Can J Anesth 2007; 54: 977-84.

Veillette Y, Dion D, Altier N, Choinière M. The treatment of chronic pain in Québec: a study of hospital-based services offered within anesthesia departments. Can J Anesth 2005; 52: 600-6.

The British Pain Society. National Pain Audit Final Report 2010–2012. Available from URL: https://www.britishpainsociety.org/static/uploads/resources/files/members_articles_npa_2012_1.pdf (accessed October 2019).

Manchikanti L, Hirsch JA, Pampati V, Boswell MV. Utilization of facet joint and sacroiliac joint interventions in Medicare population from 2000 to 2014: explosive growth continues! Curr Pain Headache Rep 2016; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-016-0588-2.

Friedly J, Chan L, Deyo R. Increases in lumbosacral injections in the Medicare population: 1994 to 2001. Spine 2007; 32: 1754-60.

Cunningham CT, Quan H, Hemmelgarn B, et al. Exploring physician specialist response rates to web-based surveys. BMC Med Res Methodol 2015; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-015-0016-z.

National Physician Survey. 2014 Response Rates. http://nationalphysiciansurvey.ca/surveys/2014-survey/response-rates/ (accessed October 2019).

Gupta S, Gupta M, Nath S, Hess GM. Survey of European pain medicine practice. Pain Physician 2012; 15: E983-94.

Kortum FC, Brascher AK, Schmitz-Buchholz D, Feldmann RE Jr, Benrath J. Interventional pain therapy. Results of a survey among specialized pain physicians in Germany (German). Schmerz 2014; 28: 591-9.

Author contributions

Harsha Shanthanna contributed to all aspects of this manuscript, including study conception and design; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; and drafting the article. Anuj Bhatia, Mohan Radhakrishna, and Jason W. Busse contributed to the study conception and design, interpretation of data, and drafting the article. Emilie Belley-Cote contributed to translation of the survey to French, interpretation of data, and drafting the article. Thuva Vanniyasingam contributed to analysis of data and drafting the article. Lehana Thabane contributed to design, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting the article.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding statement

None.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Steven Backman, Associate Editor, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shanthanna, H., Bhatia, A., Radhakrishna, M. et al. Interventional pain management for chronic pain: a survey of physicians in Canada. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 67, 343–352 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-019-01547-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-019-01547-w