Abstract

Discussions on organizational models and work in the platform economy often center on Uber as a prominent example of a digital marketplace that relies on venture capital and gig labor from self-employed drivers. This focus on Uber underestimates the diversity of organizational models and work types that likely arise from struggles between firms seeking to dominate emerging fields. Our exploratory results coming out of the field of “shared mobility” in Germany show that the platform economy harbors two modes: a few digital marketplaces with gig labor and many app-enabled firms that build on smartphones to operate their mobility services with employees that perform app-enabled labor. In addition, some firms that rely on venture capital face several firms financed by incumbents from adjacent fields—in particular, car manufacturing. Overall, we find an absorption of platform technology by incumbents alongside disruption induced by start-ups. We conclude that German shared mobility comprises a diversity of organizational models and work types beyond the Uber model, the mapping of which helps toward a better understanding of the platform economy.

Zusammenfassung

Diskussionen über Organisationen und Arbeit in der Plattformökonomie fokussieren oft Uber als prominentes Beispiel, das auf Risikokapital und einem digitalen Marktplatz für solo-selbstständige Fahrerinnen und Fahrer aufbaut. Dieser Fokus auf Uber unterschätzt die Vielfalt organisationaler Modelle und Arbeitstypen, die sich herausbilden, wenn Firmen um die Dominanz in entstehenden Feldern kämpfen. Unsere explorativen Ergebnisse aus dem Feld der „Shared Mobility“ in Deutschland zeigen, dass die Plattformökonomie zwei Modi beinhaltet: wenige digitale Marktplätze mit Selbstständigen und viele App-gestützte Firmen, die Smartphone-Technologie nutzen, um ihre Mobilitätsdienstleistungen anzubieten und dabei Arbeitskräfte beschäftigen, die App-gestützte Arbeit erbringen. Darüber hinaus stehen nur einige Disruptoren, die als Start-Ups risikokapitalfinanziert sind, vielen anderen Firmen gegenüber, die von etablierten Unternehmen aus benachbarten Feldern finanziert werden und Plattformtechnologie absorbieren. Wir schlussfolgern, dass das Feld der „Shared Mobility“ in Deutschland eine Vielfalt organisationaler Modelle und Typen von Arbeit umfasst, die weit über das Uber-Modell hinausgeht. Nur eine genauere Analyse dieser Vielfalt ermöglicht es, die Dynamiken der Plattformökonomie besser zu verstehen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Established organizational models transform and new work types proliferate in the context of the rise of the platform economy (Kenney and Zysman 2016), sharing economy (Schor 2014; Maurer et al. 2020), or platform capitalism (Davis 2016a; Langley and Leyshon 2017). In this process, a number of mobility providers offer shared rides, cars or micromobility vehicles such as e‑scooters or e‑bikes via smartphone apps. The providers often advertise this development as a part of what many consider a social-ecological transition using platform technology to provide alternative means of mobility. Besides the commonly advertised strive for more sustainability, the general perception of organization and work feeds on Uber technologies as being a prime example of an emerging field that we call the “shared mobility sector”. Because of its aggressive market strategy and its worldwide expansion, Uber dominates public discourses and scientific inquiries. However, the narrow focus on Uber nurtures a problematic oversimplification by equating one organizational model and work type with the entire field.

Many researchers noted that Uber established a particular organizational model that involves venture capital financing, and an aggressive strategy to disrupt an established industry by introducing a digital marketplace. This particular organizational model also enables a specific work type, in which Uber drivers perform services on a self-employed basis that many consider a form of hyper-precariousness (Davis 2016a; Peticca-Harris et al. 2018). Adjacent, emerging mobility services, such as Lime relying on hyper-precarious “Juicers” to charge e‑scooters, seem to merely extend the Uber driver template to micromobility. For several authors, Uber and other prominent companies thereby exemplify the essence and destination of the digital transformation of work and organizations (e.g., Nachtwey and Staab 2015; Davis 2016b; Rosenblat 2018). Hence, it might only seem reasonable to equate the Uber model with the dominant development of the platform economy or platform capitalism and extend it to shared mobility.

However, such a simplified and narrowed perspective gravitates toward capital or technical determinism (see Evers et al. 2018), falsely anticipating development trajectories from one prominent model. Such positions disregard diversity and choice. It also overlooks the volatile competition among several platforms and overestimates the magnitude of shifts (Dolata 2019) by neglecting struggles with incumbents from the taxi industry, but also from adjacent industries. Uber in particular faced substantial regulatory backlash by national political economies, rendering the most disruptive model practically illegal in several countries, for instance, Germany (Thelen 2018). Finally, platform economy research increasingly engages with the fact that the platform economy harbors various organizational models (Schor 2014; Scholz 2016) alongside diverse types of work (Kenney and Zysman 2019; Vallas and Schor 2020). Here, a narrow focus on Uber thwarts the unpacking of the complex interrelations shaping organization and work in the platform economy. Until now, the research did not adequately represent the diversity of organizational models and work types in the German shared mobility field.

To address this research gap, we combine theoretical lenses from economic sociology and the sociology of work to expand upon current findings. Building on the established lenses and current findings from the platform economy literature, we explore first empirical evidence on shared mobility in Germany. Our empirical cases comprise mobility services for ridesharing, carsharing, and micromobility sharing that operated in the two largest German cities, Berlin and Hamburg, between 2019 and 2020. Our exploratory study reveals that two modes of organizational models and work types in the German shared mobility sector coexist. The patterns and interrelations thrive on dynamics between challengers and incumbents from adjacent fields, such as automotive, car rental, and tech companies.

2 Theoretical Lenses and Insights from Platform Economy Research

2.1 Sources of Diversity of Organizational Models and Work Types

To understand the sources of diversity of organizational models and work types, two theoretical approaches provide valuable insights: the conception of control at the organizational level and the conception of work at the work level.

2.1.1 Organizational Models and the Dynamics Between Challengers and Incumbents

Neil Fligstein (2001) proposed the idea of a conception of control to understand how firms interact and what shapes their organizational models. A conception of control comprises a model of how a firm is organized. This includes key aspects of corporate governance (such as ownership structures and capital sources) as well as the organizational structures that make up the firm itself (hierarchies, relations to suppliers and workers). Additionally, a conception of control provides a worldview for the firm to identify and understand the activities of competitors, as well as a guideline on how to behave in a market.

Following Fligstein, a market constitutes a field where a fundamental dynamic involves incumbents and challengers (see also Bourdieu 2005). Challengers try to overturn established models and worldviews to introduce their conception of control. Incumbents defend their positioning. This struggle faces limits because cutthroat competition jeopardizes the survival of all the firms involved (Fligstein 2001; Beckert 2009). Thus, a viable conception of control moderates competition. Often, the state and its organizations devise regulations that mitigate competitive hazards, laying out basic rules that govern a firm’s activities (Bourdieu 2005). Over time, dominant conceptions of control shift—even as involved actors tend to favor stable market orders (Fligstein 2001; see also Fligstein and Shin 2007). New market opportunities often emerge close to existing markets, sometimes absorbing novel patterns as well as extending relations from adjacent fields. As new technologies or regulations allow for alternative models in existing industries or create new markets, struggles gain momentum (see also Dolata 2008, 2018).

One seminal, historic example of how firms regulate competition and cooperation differently was presented by Piore and Sabel (1984), arguing that the decline of markets for mass production gave rise to “flexible specialization” as a new principle of organizational models. A shifting market demand, computer technology, and regulatory backing enabled novel ways of producing goods and competing. Here, the international comparison revealed diverse organizational models (Piore and Sabel 1984, p. 265 ff.)Footnote 1 that each embodied variants of the core principles. This very organizational shift is often considered the starting point for what later became known as flexible production models or “Post-Fordism” (Vallas 1999).

The decline of Fordist mass production firms and the rise of more flexible organizational forms have since provided a dominant undercurrent for major organizational developments. The trend toward outsourcing firm functions to subcontractors (Kakabadse and Kakabadse 2002) or franchising corporate activities to smaller, legally independent units (Rometsch and Sydow 2006; Biber et al. 2017) increased the flexibility in particular. Many consider this development a steady decline of organizational models from large hierarchical firms to increasingly smaller, detached units of economic activity, which some analyze as fragmented value chains (Flecker and Schönauer 2016). In the process, organizational models shifted in a variety of ways toward more flexible patterns.

2.1.2 Diversity of Work Types as a Result of Major Transformations

The organizational shifts of the earlier decades coincide with similarly dramatic shifts in the ways in which work is organized. Here, also, the term Post-Fordism marked a pivotal point where new forms of work proliferated. Using the term conception of work, Vallas (1999) engaged with these dramatic shifts in the working world. He argues that the historical debate on flexibility and Post-Fordism denotes a progression from a Fordist mass production conception of work to a post-Fordist conception, whereby the latter is aimed at achieving greater flexibility. Firms introduced new production technologies to cope with increasing volatility and shifting demand patterns on their markets. In turn, bureaucratic models shifted toward more flexible work patterns, granting workers more discretion (Piore and Sabel 1984; Kern and Schumann 1984). The same process, however, also remodeled work according to the outlines of the “flexible firm” (Atkinson 1984; Kalleberg 2001), with outsourced and subcontracted employment relationships.

In his critical engagement with the literature, Vallas (1999) points out that debates on Post-Fordism have focused on core workers in core industrial sectors.Footnote 2 A focus on survivors and beneficiaries of the transformation process often overlooked the simultaneous growth of an externalized labor force, which only later became recognized as an integral part of the transformation. So, rather than fostering one single work pattern, the seminal shift entailed disparate and dualistic tendencies, through which simultaneous and interrelated transformations resulted in various patterns for several groups of workers. In this sense, the substantial transformation process produced a configuration of interlinked work types that involved diverse groups and produced diverse outcomes across groups.

2.2 Organizational Models and Work Types in the Platform Economy

The rise of the platform economy thrives on various technological innovations (Kenney and Zysman 2016), including cloud computing hosting scalable web services, mobile devices enabling Internet access practically everywhere, and GPS technology tracking mobile devices. Evans and Gawer (2016) note that platforms come in many different types and applications. Through their novel services, digital platforms challenged established market orders and incumbent providers, causing regulators to engage with the development (Kirchner and Schüßler 2020). In keeping with a proclaimed spirit of disruption, many companies operating platforms did not ask for permission, advancing their business models aggressively (Kenney and Zysman 2016). However, eventually regulators reacted to the development, creating a sometimes more, sometimes less restrictive framework for the digital platforms to operate in (see Collier et al. 2018; Thelen 2018; Adler 2021).

In the early period, Uber emerged as an exemplary case. It attracted attention by behaving most aggressively toward incumbents and regulators. The speedy conversion of the US taxi industry served as a role model for other firms. For Davis (2016b), Uber’s radical marketization of transport services marks a long-term erosion of traditional organizational models. This erosion process was already advanced by the outsourcing or franchising, enabling more flexible organizational models and work types (Kirchner and Schüßler 2020). In Davis’ perspective, Uber presents just the most recent installment of this steady transformation, culminating in a contagious “Uberization” of the whole economy.

Starting with Uber and moving beyond this exemplary case, we now consider the organizational models and work types that might have emerged within the platform economy.

2.2.1 Organizational Models in the Platform Economy

Uber’s organizational model comprises various elements that signify a distinct way of establishing and operating a digital platform. Uber does not employ drivers or own the required cars and instead facilitates transactions between the two sides of the market (see Evans 2012) by operating as an intermediary between drivers and passengers (Davis 2016b). In addition, Uber exemplifies the close connection between the rise of digital platforms and venture capital. Langley and Leyshon (2017); see also Ferrary and Granovetter (2009) note that platforms such as Uber perform the strategies of venture capitalists, investing large amounts and hoping to gain from quasi-monopoly returns.

The aggressive behavior by Uber and other platforms reflects a general dynamic in the emerging platform economy. Major internet companies (Dolata 2015, 2019) exploit opportunities and aim for quasi-monopoly positions through network effects. A constant volatility unfolds owing continuous threats of challenges from other platforms and shifting supply and demand patterns. This leads to fierce competition in the platform economy, with each platform hoping for market consolidation in their favor. The vast amounts of capital that poured into this structure attracted start-ups that strive to dominate markets or become acquired by one of the larger companies. Acquisitions fulfill exit strategies of investors (Kühl 2003; Langley and Leyshon 2017) who hope to cash in on the strategies of larger businesses to acquire adjacent and complementary start-ups (Dolata 2015).

Looking beyond Uber, the platform economy fostered the emergence of an abundance of many different platforms (Dolata 2019), and adequately classifying their diversity remains an unsolved challenge. Considering the general characteristics, we can highlight several prominent organizational models in the debate: Internet companies, such as Uber, operate a digital marketplace (Kirchner and Schüßler 2019) for their own profits by providing a digital infrastructure matching self-employed sellers with buyers of a particular service. Another type comes into play when authors highlight the relevance of alternative organizational forms in particular, as platform cooperatives (Scholz 2016; Thäter and Gegenhuber 2020) that empower service providers as platform owners to participate in decision-making processes.

2.2.2 Work Types in the Platform Economy

The Uber case often also serves as an example of a specific work type. Many articles stress that self-employed drivers chauffeuring for Uber constitute cases of highly precarious working conditions (e.g., Davis 2016b; Malin and Chandler 2017; Peticca-Harris et al. 2018). This type of work allows for a high degree of flexibility in working hours but also exhibits a digital system of rules, rewards, and soft controls (Rosenblat and Stark 2016) that others labeled algorithmic management (Lee et al. 2015; Beverungen 2017).

However, like the organizational models above, the debate increasingly started to engage with the diversity of work efforts that proliferates in the wake of the platform economy. Recent overviews underscore a diversity of work types (Kenney and Zysman 2019; Vallas and Schor 2020). First, there are various paid work efforts that are carried out based on a direct contractual relationship with the firm that operates a platform. Such relationships include formal employment at the platform firm and extend to direct subcontracting by the platform firm to freelancers or other firms. Second, authors highlight platform-mediated work efforts that include tasks coordinated exclusively via apps or websites. Such work efforts do not rely on a direct contractual labor relationship with the platform firm. Some of these work efforts are directly requested by buyers and paid for via the digital platform, whereas other efforts receive no direct remuneration, such as users uploading content or reviewing performance (see Kleemann et al. 2008; Orlikowski and Scott 2014; Voß 2020).

Although existing typologies highlight the diversity of work in the platform economy, they tend to focus on pertinent cases equating particular work efforts with particular relationships to the platform firm (see Kenney and Zysman 2019). A core work type describes activities by employees at the platform firm as “venture labor” (Neff 2012), tasked with the design of software infrastructures and the coordination of activities by algorithmic management. Another work type accounts for in-person services (Kenney and Zysman 2019), highlighting the work efforts of self-employed Uber drivers responding to requested “gig work” and being paid via a digital marketplace. With a heavy focus on Uber and cases from the USA, it often goes unnoticed that the platform economy comprises significant “outliers.”

European cases in particular provide “outliers” that do not fit well with general taxonomies. In Germany, the food-delivery service Foodora (now Lieferando) and the household cleaning service Book-a-Tiger also run smartphone apps that appear very similar to digital marketplaces—except for the fact that service providers enjoy formal employment status (Schmidt 2017; Ivanova et al. 2018). A study in Belgium observed comparable patterns (Drahokoupil and Piasna 2019). These service firms do not operate a digital marketplace for self-employed persons. Still, these firms also extensively employ platform technology (especially smartphone–app interfaces, GPS tracking) so that processes resemble many work practices in digital marketplaces (Ivanova et al. 2018). These firms that operate a service with apps and employees are often also considered part of the platform economy, even without running a digital marketplace, such as Uber.

2.2.3 Interrelations

The presented understandings underline that instead of advancing merely one organizational model and one work type, the platform economy likely comprises diversity. This speaks for the malleability of platform technology, allowing various organizational models to be applied to various value creation processes involving diverse work types. Hence, we can integrate the organization level and the work level.

In Fligstein’s (2001) seminal approach, the conception of control generally relates to conceptions of work as the organizational models comprise work organization as well as the general relationships with workers. The elaborations on the conception of work by Vallas (1999) provide a detailed account. Concerning work types, it is important to note that the market as a field potentially comprises diverse organizational models, reflecting struggles between challengers and incumbents. The historical example of Post-Fordism and the theoretical considerations underline that in a period of transformation societal dynamics between challengers and incumbents will foster competing organizational models and allow for a proliferation of several but interrelated work types that correspond to underlying conceptions of work.

Two counteracting mechanisms drive diversity. Isomorphic forces (DiMaggio and Powell 1983) pressure firms to adopt similar models in order to become recognized as legitimate actors in a field. Conversely, competition between incumbents and challengers invites firms to differentiate themselves from their competitors by introducing alternatives and establishing niches (see Beckert 2009; Arora-Jonsson et al. 2020). Whereas start-up challengers might follow the path laid out by the radical Uber model, other actors may also absorb platform technology but do so by introducing other organizational models and work types.

The following sections apply this framework to empirical material on the German shared mobility sector.

3 Exploration: Cases, Data Sources, and Procedures

For our research, we consider firms that enable shared mobility services for consumers, which is part of a general transformation sometimes called “new mobility” (Behrendt et al. 2020; VDV 2020). Our analysis focuses on highly delocalized services (Kirchner and Beyer 2016) operating exclusively with a smartphone app and handling a high spatial dispersion of persons and vehicles. We assume that the underlying configurations of social forms and digital systems in these cases exemplify general implications for organizational models and work types.

We selected individual shared mobility services from ridesharing, carsharing, and micromobility sharing. These services offer customers a vehicle that they share with others (either at the same time or consecutively) and access via a smartphone app. We also only included free-float systems that allow for requesting, using, parking, or leaving available vehicles everywhere in the service areas.Footnote 3 Because of capital requirements, we consider only powered vehicles. All selected cases operate at least in one of the two largest German cities, Berlin (3.7 million inhabitants) and Hamburg (1.8 million inhabitants) and have been providing their services between 2019 and 2020. In total, we considered 20 cases in our analysis (see Table 1).

Ridesharing services proliferated in the wake of successful mobility platforms, such as Lyft and Uber, that introduced digital marketplaces to mediate between drivers and passengers. In Germany, however, Uber itself faced a substantial public as well as a legal backlash, culminating in a subsequent ban of Uber’s original business model (see Thelen 2018). The case of Uber trying to enter the German market reinforced the existing legal framework regulating the taxi market according to which—among other provisions—only licensed taxi drivers may offer rides and tariffs are set by decree. Some ridesharing services, such as Moia and Berlkönig, obtain their legally required license according to an experimentation clause in German Passenger Transport Act (PBefG).Footnote 4 Ridesharing services such as FreeNow are aiming for more comprehensive reforms of the legislation to abolish certain obligations for rental car services (e.g., returning to the firm’s headquarters after each driving assignment) as well as eliminating the distinction between taxis and rental cars.

As for ridesharing, the German legal framework for carsharing is also in flux. Since 2017, a federal law has existed setting a regulatory framework to allow for the preferred treatment of carsharing services, for example, concerning the use of parking spaces. Municipalities may foster carsharing by, for instance, providing designated parking spaces or lower parking fees.

Micromobility sharing covers services that offer various types of smaller, powered vehicles ranging from seated or standing e‑scooters to power bicycles or e‑bikes. As a digital mobility service, the micromobility field was pioneered by companies like the US start-up company Bird. The micromobility sharing market constitutes an emerging field that operates in a short-distance niche left by public transportation and other sharing concepts. The use of powered standing e‑scooters in German road traffic has been allowed since June 2019. Further regulations are left to the municipalities, also those concerning the other micromobility services.

For the purposes of an initial exploration of the field, we used various publicly available data sources. This included: company websites and company reports; apps and websites, including general descriptions of the service and additional user information (e.g., frequently asked questions); job advertisements of the mobility service providers; public news coverage of the services in the two cities Berlin and Hamburg; online videos and podcasts, including provider interviews, customer reviews or documented everyday work processes.

We systematically collected the data and extracted the relevant information. We obtained the information according to the theoretical concepts outlined above, identifying aspects of organizational models and work types. Additionally, we conducted a limited number of personal interviews with field experts and other involved actors (representatives of trade unions and employees, as well as business associations) to additionally explore the field and gain a broad overview of current developments. The interviews were not systematically analyzed but allowed for a better understanding of the field and current dynamics.

4 Exploratory Results

Our exploratory results show that all selected shared mobility services operate as follows: registered users access digital platforms via mobile devices. Platforms match demand and supply, and locate users and vehicles via GPS within a designated service area. Users drive vehicles themselves or request a shared ride with a designated driver. Some platform companies match the demand directly as service providers, whereas other platforms mediate between supply and demand. The following sections report our exploratory results in detail, starting with the organizational models and work types.

4.1 Organizational Models: Digital Marketplaces and App-Enabled Firms

The organizational models comprise the general organizational structures of the mobility services, major capital sources, as well as the general relations shaping the market order and competition.

Considering organizational models, firms that use smartphone apps and employees to operate a service for general consumers dominate the shared mobility sector. This type of app-enabled firm applies to all services with two notable exceptions in ridesharing. Only FreeNow and Hansa-Taxi operate a digital marketplace for mostly licensed taxi drivers, whereby ridesharing merely represents a small subsegment to their core business of mediating regular taxi rides. FreeNow and Hansa-Taxi match consumers’ requests and available taxi rides and handle payments. Taxi drivers—often self-employed—operate independently and decide to meet a request or not. FreeNow provides a digital platform that requires registration and raises transaction fees. Hansa-Taxi, in contrast, requires fee-based membership in a cooperative, by which the digital platform transposes the traditional radio taxi mediation. The Hansa-Taxi cooperative differs considerably from the model of platform cooperatives in the debate, given that it has been incumbent for over 40 years. In contrast to the core Uber model, FreeNow and Hansa-Taxi operate within tight boundaries set by local taxi regulators and thus only partially organize the market (see Ahrne et al. 2014). Local authorities directly rule on fares, driver volume, and the eligibility of drivers (by official licensing), foreclosing many aspects of the Uber marketplace model in the US and allowing the market organizers to decide only on limited aspects of their platforms.

Considering the major capital sources in the shared mobility sector, the field bifurcates into two distinct subsets. Especially in the subfield of micromobility, venture capital provides the dominant capital source. Almost all micromobility services in our field are American or European venture capital-financed start-ups. Merely the e‑scooter provider Coup, which ceased operations at the end of 2019, relied on capital from the German company Bosch. In contrast, in the subfield of carsharing, only Miles established its service building on venture capital. All remaining carsharing and ridesharing services build on support by incumbents from adjacent fields from the conventional economy. This includes the car rental company Sixt running SIXTShare, as well as the car manufacturers Volkswagen, Daimler, and BMW indirectly supporting or directly operating ShareNow, FreeNow, WeShare, Moia, and Berlkönig. This picture of incumbents is completed by the public transportation providers Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe (BVG), the administrator of Berlkönig, the Hansa-Taxi cooperative running a ridesharing service, and Deutsche Bahn being responsible for the CleverShuttle ridesharing service.Footnote 5 Especially in ridesharing, some of the services are backed by complex firm networks, such as a joint venture by Daimler and BMW or the joint venture by Mercedes Benz Vans and the American company Via.

An underlying dynamic in carsharing and ridesharing, therefore, derives from the attempts of incumbents from adjacent industries, such as car rental, car manufacturing, and public transport companies to extend their conventional business by absorbing platform technology. This pattern resembles an absorption by incumbents enabled by the opportunities of digital platform technology prone to seizing shares in emerging markets and solidifying their positions in volatile times. In addition, the micromobility subfield exhibits substantial ties to large tech firms. This includes personal ties, as former key employees and CEOs of these firms founded several micromobility services (e.g., Bird, Lime, Tier). Ties also exist through investments by major tech firms such as Alphabet and Uber (e.g., Lime), suggesting that the shared mobility sector constitutes a battlefield for actors from adjacent industries to advance their businesses and dominate the emerging market.

The contours of the relations shaping the market order and competition are revealed considering a general trend that appeared in our analysis. Fierce competition leads to market concentration as competitors cease their operations (e.g., CleverShuttle in our two cities, Coup) or are strategically acquired and integrated by their competitors (e.g., Uber Jump by Lime, Circ by Bird). Furthermore, firms try to dominate the market by superimposing themselves on their competitors. This pattern of superimposition currently culminates in creating platforms or super-platforms (Frenken 2017; Vallas and Schor 2020). In Berlin, the transport company BVG operates Jelbi, integrating selected micromobility, carsharing, and ridesharing services alongside the public transportation services (the public transportation company in Hamburg operates a similar platform called “hvv switch”). In contrast to these public platform approaches, the car manufacturers Daimler and BMW combine their mobility services in the ReachNow app, creating a for-profit platform for mobility services. Most recently, FreeNow, also owned by Daimler and BMW, started integrating several other providers into its app, including Voi and Miles. In addition, displaying shared mobility services in Google Maps or the integration of Lime into the Uber app signal a similar trend. Generally, in shared mobility, various organizational models compete. Overall, relations follow a pattern where start-up firms and incumbents from adjacent fields try to dominate the market.

4.2 Work in German Shared Mobility: Gig Labor and Beyond

As sketched out above, the platform economy literature assumes the existence of various work types comprising specific activities by various persons. However, in their effort to capture the complexity of work in the platform economy, existing typologies remain complex themselves, as they draw on various criteria to differentiate between work types, meaning the type of activity (e.g., in-person service work, creating the platform), employment status (e.g., regular employment contract, self-employed), and working conditions (e.g., precarious, full-time) at the same time. In the following, we start by focusing on activities to ascertain the various relationships between the platform firm and work types in our cases.

Our exploration of work types started by identifying several activities that we deemed to be key for the service that the platform firms provide.Footnote 6 We considered activities that directly relate to platform technology or to the vehicle that provides the material basis for the digital mobility service (see also Behrendt et al. 2020, p. 6). From our material, we generated a shortlist of activities that we observed with reasonable consistency across the different platforms. To manage the complexity, we bundled these activities into three categories: managing (creating, operating, and managing platform and user activity—including setting work shifts and breaks); driving (driving vehicles); maintaining (reporting errors, performing security checks on vehicles, cleaning and repairing vehicles, recharging or refueling vehicles, physically reallocating vehicles in the service area).

Confronting the general taxonomies of diverse work types in the platform economy (Kenney and Zysman 2019; Vallas and Schor 2020) with our bundled activities, we encounter congruence alongside substantial deviations in several of our cases:

Generally, activity bundle management exhibits a high degree of congruence. All shared mobility services employ architects and algorithmic managers performing venture labor. Only for the two digital marketplaces, Hansa-Taxi and FreeNow, the taxonomy applies well for gig work, as driving is performed mostly by self-employed persons coordinated by a smartphone app. Furthermore, so-called Juicers or Hunters, which some micromobility apps allow to collect, recharge and reallocate e‑scooters in the service area, are self-employed on a piece-rate pay basis. However, Lime and Voi abandoned gig labor in late 2019 and early 2020. Other than that, we find employment relationships for maintaining activities on all app-enabled firms and for driving activities on ridesharing services. Following the app-enabled firm model, firms directly or by direct subcontractors employ persons as staff to perform the activities required to provide the service.

Additionally, our findings also fit reasonably well with patterns of user labor, mostly without renumeration. However, user efforts extend beyond the mere creation of platform content, such as reviews or feedback. Although users of Moia may merely provide service feedback, the absence of in-person service work at providers such as ShareNow or Voi motivates carsharing and micromobility services to involve users more extensively. Firms encourage users to report damage or problems and they are required to perform basic checks to make sure the vehicle is in proper physical condition or parked safely. Some carsharing platforms require or enable their customers to fuel or recharge the vehicles at gas stations or charging stations. It is worth noting that for many micromobility and carsharing platforms we find a substantial overlap between user labor and maintaining activities by employed staff. Some activities can be performed by employees as well as users, indicating that work types and activities do not necessarily constitute mutually exclusive categories. Our cases partly rely on the ability to allocate certain activities to various, distinct work types.

Up to this point, our exploration has consistently revealed a type of work that is not well covered by the extant taxonomies. This surplus type pertains to driving activities for Moia, CleverShuttle, and Berlkönig as well as to maintaining activities of many other app-enabled firms. At several shared mobility firms driving and maintenance are performed by employees with a direct employment relationship (or directly subcontracted employment). We call this work type app-enabled labor, as it covers paid work efforts of employees to uphold the shared mobility service. Although the day-to-day operations of app-enabled labor resemble many aspects of gig labor, platform technology allows for one work type with a formal employment status and another work type only with self-employment.

4.3 Mapping the Interrelations: The Two Modes of German Shared Mobility

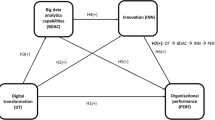

In line with existing theory, we observe a shift of organizational models owing to struggles between incumbents and challengers—especially in historical transformation periods. Whereas the shift from Fordism to Post-Fordism enabled the “flexible firm” (Atkinson 1984), Davis (2016b) anticipates a similar shift toward an “Uberization” of the whole economy, disintegrating the flexible firm into a “webpage enterprise” and shifting to self-employed work. However, considering our exploration of the German shared mobility sector, the organizational models split up into two modes. Table 2 reports their characteristics.

Mode 1 firms run a digital marketplace and rely on gig labor. Mode 2 covers app-enabled firms that run their service with employees using smartphone apps to coordinate their activities utilizing app-enabled labor. The distinct reliance on a particular work type corresponds to a specific application of platform technology: for app-enabled firms, smartphone technology serves as an “innovation platform” (Evans and Gawer 2016; Gawer and Srnicek 2021) that firms build on to implement their own services. Mode 2 firms merely utilize platform technology but do not become platforms themselves. In contrast, though also using smartphone technology, digital marketplaces directly mediate between providers and consumers of a service on their own platform, thereby realizing what has been called a “transaction platform” (Evans and Gawer 2016; Gawer and Srnicek 2021). Thus, Mode 1 firms also build on smartphone technology but operate their own platform.

However, although the reliance on gig labor and app-enabled labor seems to depend on the type of platform implementation, venture labor and user labor always contribute to organizational models in both modes. Here, we see the contours of two conceptions of work in German shared mobility that each comprise interrelated work types. Although Mode 1 firms utilize gig, venture, and user labor, the firms in Mode 2 rely on app-enabled, venture, and user labor. Hence, diverse applications of platform technology correspond to and allow for diverse conceptions of work: one with self-employment at the frontline, and one with employees.

In congruence with the diverse work types, the working conditions vary, such as employment status and key rewards (see Munoz de Bustillo et al. 2011). For managing activities we generally find good working conditions, realizing the benefits of venture labor alongside potentially higher work intensity (see Neff 2012). Gig labor covers self-employed taxi drivers and Juicers with high volatility and comparably low wages. Platform technology also increasingly allows for user labor and enables business models that partially replace paid work efforts increasing users’ share in the value-capturing process. User labor challenges general frameworks for working conditions as the lack of a formal status and participation rights defies established taxonomies. Considering app-enabled labor, Moia, a 100%-owned Volkswagen subsidiary, provides a compelling example. Although Moia employs drivers, the conditions vary, ranging from minor to regular part-time employment contracts with varying hours, thus exhausting established regulatory frameworks of the “flexible firm”.Footnote 7 Still, app-enabled labor by Moia drivers lacks many of the dire drawbacks of self-employment in the Uber model.

The presence of two modes in the German shared mobility sector questions the reach of the Uber model as a general template. Figure 1 shows how the cases relate to the two core aspects of the Uber model: the reliance on gig labor and the involvement of venture capital. The predominant model for carsharing and ridesharing involves no gig labor and no venture capital as it predominantly marks the absorption of platform technology by incumbents from adjacent fields, such as car manufacturing or car rental. This applies with the notable exemption of the venture capital funded carsharing case of Miles. The additional model for ridesharing relies on gig labor without venture capital and denotes a digital extension of the established taxi service by incumbents from the taxi business or automotive industry. Here, a few platform firms transposed the role of established taxi intermediaries to a digital format. During our observation period, the ridesharing service CleverShuttle ceased operations in both of the cities observed, giving in to fierce competition. In micromobility sharing, however, almost all cases rely on venture capital applying a start-up template to their business models and often relying on financial as well as personal ties to major tech firms. Coup, the only micromobility case with the financial backing of an incumbent, ceased operations in 2019. After initial experiments by some, all observed micromobility cases abstained from gig labor, subsequently leaving the Uber model quadrant in the top left corner in Fig. 1 vacated.

Although our empirical material indicates relations of intense competition between firms in German shared mobility, the emerging picture of core features appears rather isomorphic, with the different types of services neatly conforming to combinations of gig labor usage and reliance on venture capital. The absence of venture capital in ridesharing and most carsharing cases coincides with strong ties to incumbents in adjacent fields that absorb platform technology to expand their activities. Gig labor played only a minor role in some micromobility cases and currently merely extends to the established taxi business via ridesharing. Overall, app-enabled firms dominate the German shared mobility sector relying on employees who perform app-enabled labor. We labeled these firms Mode 2 cases. The two digital marketplaces that we classified as Mode 1 cases remain a minority model. Hence, the Uber story and “Uberization” poorly represent the actual patterns and diversity in the field. The shared mobility segment of the German platform economy operates predominantly without gig labor and without venture capital.

5 Discussion and Conclusion

This article explored how organizational models and work types in the shared mobility sector interrelate by examining German carsharing, ridesharing, and micromobility sharing services. We theorized that the focus on Uber’s organizational model and one work type does not sufficiently represent the diversity and struggles shaping the shared mobility field in the German platform economy. Our exploration finds two underlying modes that build on diverse organizational models and work types.

Considering organizational models, we find a diversity dominated by app-enabled firms where smartphone apps facilitate a service to consumers provided by employees. We identified only two digital marketplaces in the ridesharing field that also merely mediate for licensed taxi drivers. Both marketplaces represent an updated digital platform model of the established taxi market that now also includes a ridesharing option. Whereas venture capital dominates micromobility, it plays only a minor role in ridesharing and in carsharing. The latter two fields mostly rely on endowments by incumbents from adjacent industries, especially from car manufacturing and car rental firms. In contrast, micromobility exhibits personal and corporate ties to large tech firms, such as Google (Alphabet) and Uber, reflecting diverse actors competing in the German shared mobility sector.

In terms of work types, our findings reveal that shared mobility relies on diverse but interrelated work types. Some patterns follow current general taxonomies (Kenney and Zysman 2019; Vallas and Schor 2020), e.g., “venture labor” performed by well-paid employees of the platform firms managing the digital infrastructures and the activities on the platform. In addition, work performed in the two digital marketplaces for licensed taxi drivers exhibits characteristics of platform-mediated in-person service work, called gig labor, displaying some similarities with working as a self-employed driver for Uber. On close inspection, this shift is much less radical than assumed as digital technology transposes traditionally mediated taxi self-employment to a digital platform. We also found that consumers of many shared mobility services perform user labor. In contrast to mere content creation on other online platforms, several mobility services enable or even require users to perform on-site tasks, such as fueling vehicles and reporting errors.

In contrast, other findings on work efforts that concern driving and maintaining vehicles differ considerably from established taxonomies. This pattern includes employees for service provision and physical maintenance of vehicles, we called app-enabled labor. Moia and several other app-enabled firms employ a workforce to drive and maintain the vehicles directly or via subcontractors, such as service providers or staffing agencies. This confirms general considerations that platform models might take hold in the conventional economy (Vallas and Schor 2020). However, the direction seems reversed, as established companies from adjacent industries absorb platform technology to extend their business models. In this process, many firms do not break away from employment. Instead of advancing hyper-precarious self-employment the majority of shared mobility cases opt for Post-Fordist patterns continuing the path toward increased flexibility (Vallas 1999) and fissuring (Weil 2014). Thus, instead of departing from established employment relations altogether, many app-enabled firms combine platform technology with Post-Fordist patterns of the flexible firm to advance the German platform economy.

Overall, our findings confirm the theoretical assumptions drawn from the theory (Vallas 1999) that major organizational shifts come with diverse and interrelated work types. Our research revealed interrelated work types with all shared mobility services exhibiting forms of venture labor by IT specialists and user labor by consumers. Here, the most substantial shift of work patterns from Post-Fordist templates does not seem to come with gig labor, as expected by the Uberization thesis. Instead, we found that user labor systematically substitutes and complements maintenance activities, in many cases performed by employees. Additionally, as suggested by theory (Fligstein 2001), we found a dynamic among the diverse actors struggling to dominate the shared mobility sector. Although—in principle—platform technology allows for various organizational models, the fierce competition heads toward a few dominant service providers implementing work types that foster the respective working conditions.

The reliance on either app-enabled labor or gig labor lies at the heart of the two modes we found in the German shared mobility sector. In our sample, the mode of app-enabled firms providing a service with employees dominates, and only a few cases run a digital marketplace with self-employed taxi drivers. In particular, orientations of incumbents from adjacent fields and the role of institutional frameworks (e.g., regulations and labor laws) might explain the relative absence of gig labor in the German context. Going beyond mobility services, work patterns in other sectors resemble various characteristics of our cases, as firms also extensively utilize smartphone technology to coordinate app-enabled labor in food or grocery delivery as well as cleaning or postal services. Thus, our findings expand the known US-focused taxonomies on platform work and allow us to conceptually integrate European “outliers” into the debate by concluding that different applications of platform technology allow for organizational models in the platform economy with and without employees. Thus, the application of platform technology remains open to choice.

Alongside the various insights we presented, our empirical approach comes with substantial limitations. Our first exploratory results call for more in-depth research. The fact that we mostly rely on publicly available information presents preliminary evidence and confines our empirical reach. Although our approach allows us to report the clear names, often we cannot go beyond what the firms willingly report publicly. Therefore, the inner workings of the organizations—especially the modes of venture labor at the platform firm as well as the subcontracting practices—remain opaque and largely inaccessible. Here, we call for in-depth case studies of organizations and work to fill that gap. However, firms in the platform economy remain reluctant to allow access. In times where firms harvest enormous amounts of data from employees and users, it appears paradoxically hard to collect data on firms operating in the platform economy.

From a general perspective, our findings pick up on voiced reservations questioning the radicalness of the digital transformation. For example, Dolata (2019) stresses that platform business models remain fairly conventional and did not create a new industry. In contrast to the disruption induced by tech start-ups with venture capital backing, in our material on the German case, we observed a pattern of absorption by incumbents. Here, established firms from adjacent fields absorb platform technology to expand their business and try to superimpose themselves on emerging markets. This superimposition via platform technology, in fact, might constitute the very essence of the rise of the platform economy: a broader societal transformation in which some digital platforms succeed in governing adjacent markets by introducing a hierarchy among industries.

Our examination of the German shared mobility sector revealed the inadequacy of the Uber story and the Uberization thesis as a general explanation emphasizing the relevance of national conditions. In terms of political economy, the substantial changes of organizational models and work types prompt questions about the broader trajectories of institutional change within the German economy (Streeck and Thelen 2005). Although previously the German economy experienced a “vertical disintegration” (Doellgast and Greer 2007), or advancing dualism (Hassel 2014), our results indicate that platforms invite incumbents to absorb adjacent fields and markets, realizing horizontal integration. This begs the question for the German political economy whether this absorption will foster higher standards for work in the platform economy or deepen dualism. Here, the complex arrangements of subcontractors deserve attention. Although we do not observe disruptive changes of organizational models and work types according to the Uber model, app-enabled labor can still imply precarious working conditions typical for the fringes of Post-Fordist labor markets. As our cases of shared mobility services show, the working conditions realized in the German platform economy will substantially hinge on the organizational models that eventually prevail on the markets. Here, market relations translate into working conditons.

Overall, our findings underline the benefits of a perspective on challenger-incumbent dynamics in the platform economy. Our exploration reveals dynamics between the involved actors, many of which come from adjacent industries, such as auto manufacturing or tech industries. Merely echoing the dominant narratives of superior technology and capital power, like the Uber story, fails to account for the struggles of diverse actors. Platform technology, as our exploration shows, allows for diverse organizational models and work types. Hence, the transformation is not destined to follow one path for it still allows for contention, struggles, and alternatives. The German case also indicates an alternative path of digital transformation whereby several firms from the conventional economy absorb platform technology to expand from adjacent industries to the platform economy. Here, the dominant patterns of shared mobility services predominantly continue Post-Fordist patterns of organization and work, coming up short of a radical Uberization of the German economy.

Notes

This comprised so-called regional conglomerations, federated enterprises, “solar” firms, and workshop factories.

Our case selection, therefore, excludes various traditional and adjacent mobility services, such as regular individual taxi services, station-based carsharing or car rental, line-based public mass transport as well as sharing of dock-based vehicles and nonpowered vehicles (regular bikes). Many of these services constitute predecessors as well as adjacent competitors to the shared mobility firms examined.

It is also possible to obtain a license as supporting regular public transport services according to the Passenger Transport Act (PBefG – Personenbeförderungsgesetz) §§ 42 and 2(6), which includes the Hamburg public transport platform Ioki. Because of its closer connection to public transport, we have excluded this service from the purview of this paper.

Also, the services FreeNow, CleverShuttle, and Berlkönig either constitute or started out as venture capital-financed tech firms that cooperate with or have been acquired by incumbent firms from neighboring sectors.

Here we exclude general managerial, technical, or support functions that are common to many other firms (Mintzberg 1989), e.g., general management, product marketing, general human resource management, and buying or selling vehicles.

When the service commenced, Moia initially utilized temporary agency workers.

References

Adler, Laura. 2021. Framing Disruption: How a Regulatory Capture Frame Legitimized the Deregulation of Boston’s Ride-for-Hire Industry. Socio-Economic Review Online First.

Ahrne, Göran, Patrik Aspers and Nils Brunsson. 2014. The Organization of Markets. Organization Studies 36:7–27.

Arora-Jonsson, Stefan, Nils Brunsson and Raimund Hasse. 2020. Where Does Competition Come From? The role of organization. Organization Theory 1: 2631787719889977.

Atkinson, John. 1984. Flexibility, Uncertainty and Manpower Management. IMS Report No.89. Brighton: Institute of Manpower Studies.

Beckert, Jens. 2009. The social order of markets. Theory and Society 38:245–269.

Behrendt, Siegfried, René Bormann, Werner Faber, Stefan Jurisch, Ingo Kollosche, Ingo Kucz, Detlef Müller and Stephan Rammler. 2020. Mobilitätsdienstleistungen gestalten. Beschäftigung, Verteilungsgerechtigkeit, Zugangschancen sichern. WISO DISKURS. Berlin: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

Beverungen, Armin. 2017. Algorithmisches Management. In Nach der Revolution. Ein Brevier digitaler Kulturen, Hrsg. Timon Beyes, Jörg Metelmann and Claus Pias, 52–63. Berlin: TEMPUS CORPORATE.

Biber, Eric, Sarah E. Light, J. B. Ruhl and James Salzman. 2017. Regulating business innovation as policy disruption: from the Model T to Airbnb. Vanderbilt Law Review 70:1561–1626.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 2005. The social structure of the economy. Cambridge: Polity.

Collier, Ruth Berins, V. B. Dubal and Christopher L. Carter. 2018. Disrupting Regulation, Regulating Disruption: The Politics of Uber in the United States. Perspectives on Politics 16:919–937.

Davis, Gerald F. 2016a. Can an Economy Survive Without Corporations? Technology and Robust Organizational Alternatives. Academy of Management Perspectives 30:129–140.

Davis, Gerald F. 2016b. What Might Replace the Modern Corporation? Uberization and the Web Page Enterprise. Seattle University Law Review 39:501–515.

DiMaggio, Paul J., and Walter W. Powell. 1983. The Iron Cage Revisited—Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. American Sociological Review 48:147–160.

Doellgast, Virginia, and Ian Greer. 2007. Vertical Disintegration and the Disorganization of German Industrial Relations. British Journal of Industrial Relations 45:55–76.

Dolata, Ulrich. 2008. Technologische Innovationen und sektoraler Wandel Eingriffstiefe, Adaptionsfähigkeit, Transformationsmuster: Ein analytischer Ansatz. Zeitschrift für Soziologie 37:42–59.

Dolata, Ulrich. 2015. Volatile Monopole. Konzentration, Konkurrenz und Innovationsstrategien der Internetkonzerne. Berliner Journal für Soziologie 24:505–529.

Dolata, Ulrich. 2018. Technological Innovations and the Transformation of Economic Sectors. A Concise Overview of Issues and Concepts. SOI Discussion Paper 2018:1–21.

Dolata, Ulrich. 2019. Privatization, curation, commodification. Commercial platforms on the Internet. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Soziologie 44:181–197.

Drahokoupil, Jan, and Agnieszka Piasna. 2019. Work in the platform economy: Deliveroo riders in Belgium and the SMart arrangement. ETUI Research Paper-Working Paper.

Evans, David S. 2012. Governing Bad Behavior by Users of Multi-Sided Platforms Berkeley Technology Law Journal 2:1202–1249.

Evans, Peter C., and Annabelle Gawer. 2016. The Rise of the Platform Enterprise. A Global Survey. The Emerging Platform Economy Series. New York: The Center for Global Enterprise.

Evers, Maren, Martin Krzywdzinski and Sabine Pfeiffer. 2018. Designing wearables for use in the workplace: the role of solution developers. Discussion Paper. Berlin: WZB Berlin Social Science Center.

Ferrary, Michel, and Mark Granovetter. 2009. The role of venture capital firms in Silicon Valley’s complex innovation network. Economy and Society 38:326–359.

Flecker, Jörg, and Annika Schönauer. 2016. The Production of ‘Placelessness’: Digital Service Work in Global Value Chains. In Space, Place and Global Digital Work, Hrsg. Jörg Flecker, 11–30. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Fligstein, Neil. 2001. The Architecture of Markets. An Economic Sociology of Twenty-First-Century Capitalist Societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Fligstein, Neil, and Taekjin Shin. 2007. Shareholder value and the transformation of the U.S. economy, 1984–2000. Sociological Forum 22:399–424.

Frenken, Koen. 2017. Political economies and environmental futures for the sharing economy. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 375:1–15.

Gawer, Annabelle, and Nick Srnicek. 2021. Online platforms: economic and societal effects. Panel for the future of science and technology. Brussels: European Union.

Hassel, Anke. 2014. The Paradox of Liberalization—Understanding Dualism and the Recovery of the German Political Economy. British Journal of Industrial Relations 52:57–81.

Ivanova, Mirela, Joanna Bronowicka, Eva Kocher and Anne Degner. 2018. The App as a Boss? Control and Autonomy in Application-Based Management. Arbeit | Grenze | Fluss—Work in Progress interdisziplinärer Arbeitsforschung. Frankfurt (Oder): Viadrina.

Kakabadse, Andrew, and Nada Kakabadse. 2002. Trends in Outsourcing. European Management Journal 20:189–198.

Kalleberg, Arne L. 2001. Organizing Flexibility: The Flexible Firm in a new Century. British Journal of Industrial Relations 39:479–504.

Kenney, Martin, and John Zysman. 2016. The Rise of the Platform Economy. Issues in Science & Technology XXXII.

Kenney, Martin, and John Zysman. 2019. Chapter 1 Work and Value Creation in the Platform Economy. In Work and Labor in the Digital Age, Hrsg. Steven Vallas and Anne Kovalainen, 13–41. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited.

Kern, Horst, and Michael Schumann. 1984. Das Ende der Arbeitsteilung? Rationalisierung in der industriellen Produktion: Bestandsaufnahme, Trendbestimmung. München: Beck.

Kirchner, Stefan, and Jürgen Beyer. 2016. Die Plattformlogik als digitale Marktordnung. Wie die Digitalisierung Kopplungen von Unternehmen löst und Märkte transformiert. Zeitschrift für Soziologie 45:324–339.

Kirchner, Stefan, and Elke Schüßler. 2019. The Organization of Digital Marketplaces. Unmasking the Role of Internet Platforms in the Sharing Economy. In Organization outside organization, Hrsg. Göran Ahrne and Nils Brunsson, 131–154. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kirchner, Stefan, and Elke Schüßler. 2020. Regulating the Sharing Economy: A Field Perspective. Research in the Sociology of Organizations 66:215–236.

Kleemann, Frank, G. Günter Voß and Kerstin Rieder. 2008. Un(der)paid Innovators: The Commercial Utilization of Consumer Work through Crowdsourcing. Science, Technology & Innovation Studies 4:5–26.

Kühl, Stefan. 2003. Exit: Wie Risikokapital die Regeln der Wirtschaft verändert. Frankfurt a.M.: Campus.

Langley, Paul, and Andrew Leyshon. 2017. Platform capitalism: The intermediation and capitalisation of digital economic circulation. Finance and Society 3:11–31.

Lee, Min Kyung, Daniel Kusbit, Evan Metsky and Laura Dabbish. 2015. Working with machines: The impact of algorithmic and data-driven management on human workers. Proceedings of the 33rd annual ACM conference on human factors in computing systems.

Malin, Brenton J., and Curry Chandler. 2017. Free to Work Anxiously: Splintering Precarity Among Drivers for Uber and Lyft. Communication, Culture & Critique 10:382–400.

Maurer, Indre, Johanna Mair and Achim Oberg. 2020. Variety and Trajectories of New Forms of Organizing in the Sharing Economy: A Research Agenda. In Theorizing the Sharing Economy: Variety and Trajectories of New Forms of Organizing, Hrsg. Indre Maurer, Johanna Mair and Achim Oberg, 1–23. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited.

Mintzberg, Henry. 1989. Mintzberg on Management. Inside our strange world of organizations. New York: The Free Press.

Munoz de Bustillo, Rafael, Enrique Fernandez-Macias, Fernando Esteve and José-Ignacio Anton. 2011. E pluribus unum? A critical survey of job quality indicators. Socio-Economic Review 9:447–475.

Nachtwey, Oliver, and Philipp Staab. 2015. Die Avantgarde des digitalen Kapitalismus. Mittelweg 36 24:59–84.

Neff, Gina. 2012. Venture labor: Work and the burden of risk in innovative industries. Boston: MIT press.

Orlikowski, Wanda J., and Susan V. Scott. 2014. What Happens When Evaluation Goes Online? Exploring Apparatuses of Valuation in the Travel Sector. Organization Science 25:868–891.

Peticca-Harris, Amanda, Nadia deGama and M. N. Ravishankar. 2018. Postcapitalist precarious work and those in the ‘drivers’ seat: Exploring the motivations and lived experiences of Uber drivers in Canada. Organization 27:36–59.

Piore, Michael J., and Charles Frederick Sabel. 1984. The Second Industrial Divide. New York: Basic Books.

Rometsch, Markus, and Jörg Sydow. 2006. On Identities of Networks and Organizations—The Case of Franchising. In Only Connect: Neat Words, Networks and Identities, Hrsg. Martin Kronberger and Siegfried Gudergan, 19–47. Copenhagen: Liber & Copenhagen Business School Press.

Rosenblat, Alex. 2018. Uberland: how algorithms are rewriting the rules of work. Oakland, California: University of California Press.

Rosenblat, Alex, and Luke Stark. 2016. Algorithmic Labor and Information Asymmetries: A Case Study of Uber’s Drivers. International Journal Of Communication 10:3758–3784.

Schmidt, Florian A. 2017. Der Job als Gig – Digital vermittelte Dienstleistungen in Berlin. Berlin: ArbeitGestalten.

Scholz, Trebor. 2016. Platform Cooperativism. Challenging the Corporate Sharing Economy. New York, NY: Rosa Luxemburg Foundation.

Schor, Juliet. 2014. Debating the Sharing Economy. A Great Transition Initiative Essay. Online: Great Transition Initiative.

Streeck, Wolfgang, and Kathleen Thelen. 2005. Introduction: Institutional Change in Advanced Political Economies. In Beyond Continuity: Institutional Change in Advanced Political Economies Hrsg. Wolfgang Streeck and Kathleen Thelen, 1–39. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Thäter, Laura, and Thomas Gegenhuber. 2020. Plattformgenossenschaften: mehr Mitbestimmung durch die digitale Renaissance einer alten Idee? In Arbeit in der Data Society. Zukunftsvisionen für Mitbestimmung und Personalmanagement, Hrsg. Verena Bader and Stephan Kaiser, 209–223. Wiesbaden: SpringerGabler.

Thelen, Kathleen. 2018. Regulating Uber: The Politics of the Platform Economy in Europe and the United States. Perspectives on Politics 16:938–953.

Vallas, Steven P. 1999. Rethinking Post-Fordism: The Meaning of Workplace Flexibility. Sociological Theory 17:68–101.

Vallas, Steven, and Juliet B. Schor. 2020. What Do Platforms Do? Understanding the Gig Economy. Annual Review of Sociology 46:273–294.

VDV. 2020. New Mobility Forum. https://www.vdv.de/new-mobility-forum.aspx. Accessed 19 June 2020.

Voß, G. Günter. 2020. Arbeitende Nutzer und ihre Lebensführung (slightly corrected 4th version Juli 2019. The article is a pre-version of a contribution to a book edited by Jochum/Jurczyk/Voß/Weihrich—forthcoming 2019/20).

Weil, David. 2014. The Fissured Workplace: Why Work Became So Bad for So Many and What Can Be Done to Improve It. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: Harvard University Press.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dzifa Ametowobla, Ulrich Dolata and Jan-Felix Schrape for their constructive comments on earlier versions of this article.

Funding

The research for this article was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs (BMAS), as part of the “Fördernetzwerk interdisziplinäre Sozialpolitikforschung” (FIS) (project identifier: FIS.00.0014.18), it also received support in the context of the priority program “The digitalization of working worlds (SPP 2267)” funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – 442171088.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kirchner, S., Dittmar, N. & Ziegler, E.S. Moving Beyond Uber. Köln Z Soziol 74 (Suppl 1), 109–131 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-022-00830-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-022-00830-x

Keywords

- Mobility services

- Organizational models

- Markets as fields

- Labor and working conditions

- Platform capitalism