Abstract

Genomic instability is one of the hallmarks of cancer. The incidence of genetic alterations in homologous recombination repair genes increases during cancer progression, and 20% of prostate cancers (PCas) have defects in DNA repair genes. Several somatic and germline gene alterations drive prostate cancer tumorigenesis, and the most important of these are BRCA2, BRCA1, ATM and CHEK2. There is a group of BRCAness tumours that share phenotypic and genotypic properties with classical BRCA-mutated tumours. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors (PARPis) show synthetic lethality in cancer cells with impaired homologous recombination genes, and patients with these alterations are candidates for PARPi therapy. Androgen deprivation therapy is the mainstay of PCa therapy. PARPis decrease androgen signalling by interaction with molecular mechanisms of the androgen nuclear complex. The PROFOUND phase III trial, comparing olaparib with enzalutamide/abiraterone therapy, revealed increased radiological progression-free survival (rPFS) and overall survival (OS) among patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) with BRCA1, BRCA2 or ATM mutations. The clinical efficacy of PARPis has been confirmed in ovarian, breast, pancreatic and recently also in a subset of PCa. There is growing evidence that molecular tumour boards are the future of the oncological therapeutic approach in prostate cancer. In this review, we summarise the data concerning the molecular mechanisms and preclinical and clinical data of PARPis in PCa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Molecular tumour profiling is a new approach for personalised targeted therapy in cancer patients. |

PARP inhibitors are a new promising class of drugs that show clinical efficacy in genomically defined, heavily pre-treated prostate cancer patients. |

Olaparib and rucaparib were recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for prostate cancer. |

Many clinical trials are ongoing to determine the efficacy of PARP inhibitors in different prostate cancer stages, different prostate cancer hormonal statuses, and in various drug combinations. The major challenges remain the proper indication of genomic alterations with regard to the effectiveness of the treatment. |

1 Introduction

Several germline and somatic genetic alterations are associated with prostate cancer (PCa) initiation, promotion and progression [1, 2]. Hereditary PCa accounts for around 9% of PCa patients and includes germline mutations in homologous repair deficiency (HRD) and mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency genes [3, 4]. The most clinically relevant of these are mutations in the BRCA2 and BRCA1 genes (breast-cancer susceptibility gene, BRCA2/1mut), because genomic instability increases the risk of PCa development [5, 6]. BRCA1 and BRCA2 are proteins involved in homologous recombination repair (HRR), a process that repairs DNA damage [7, 8]. In vitro studies show that PCa cells with BRCA1mut and BRCA2mut are up to 1000 times more sensitive to Poly(ADP-ribose) inhibitors (PARPis) [9]. In the era of molecular biology, one new option for cancer treatment is targeting mechanisms that affect genome instability, one of the hallmarks of cancer [10, 11]. PARPis are breakthrough molecularly directed, targeted therapies that increase the therapeutic options for PCa patients (Table 1) [9, 12,13,14,15]. In May 2020, olaparib and rucaparib were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for PCa. Olaparib was approved for adult patients with deleterious or suspected deleterious germline or somatic HRR gene-mutated metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC), who have progressed following prior treatment with enzalutamide or abiraterone. Rucaparib was approved for patients with deleterious germline or somatic BRCA-mutated mCRPC who have been treated with androgen receptor-directed therapy and a taxane-based chemotherapy.

2 The Role of Poly(ADP-Ribose) (PARP) in DNA Damage

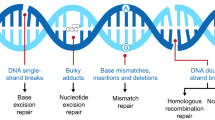

The presence of endogenous and exogenous base DNA damage increases the risk of cancer due to genomic instability. Several mechanisms are responsible for DNA damage response (DDR), depending on the type of damage. DNA repair pathways maintain the integrity of the genome by base excision repair, nucleotide excision repair, HRR, non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), translesion synthesis and MMR [7, 16]. The most common DNA damage is single-strand breaks, which are repaired with the involvement of PARP enzymes in base-excision mechanisms. Importantly, PARPs also are activated in double-strand break repair in HRR. PARP enzymes are DNA damage sensors and catalyse the transfer of ADP-ribose to target proteins via cleavage of NAD + (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) in the poly ADP-ribosylation reaction that activates the DNA repair machinery. Moreover, PARP modulates chromatin structure, and replication and transcription of DNA [17].

3 The Concept of Synthetic Lethality

DDR is the method by which cancer cells monitor and repair damaged genetic material. In cancer cells, DDR is characterised by an increased level of replication stress and a high level of DNA damage. The loss of at least one DDR pathway in cancer cells provided the background and rationale for a new drug target via the concept of synthetic lethality (conditional genetics) [18]. Inactivation of one gene allele by mutation and inhibition is not toxic for cells, but when the second pair of the gene is affected this leads to cancer cell death. Inhibition of PARP leads to DNA-repair disruption and the accumulation of single-strand breaks. This results in the creation of double-strand breaks, which, physiologically, are repaired with BRCA and PARP involvement during HRR. BRCA1 and 2 are tumour suppressors that regulate several cellular processes. BRCA1 is involved in DNA repair and checkpoint activation, whereas BRCA2 is a mediator of the core mechanism [6, 8]. If BRCA is mutated, PARP inhibition prevents DNA repair. Alternative, ineffective repair pathways are activated that lead to genome instability, cell-cycle arrest and cell death [6, 19,20,21,22]. In 2005, Farmer et al. confirmed the hypothesis that targeting PARP may be an effective treatment strategy in BRCA mutant cells [9]. Moreover, in vitro and in vivo studies show synthetic lethality phenomena between antiandrogen therapy and PARPi. Research on ovarian carcinoma has shown that high PARP activity significantly improves progression-free survival (PFS) [23]. Gui et al. suggested that PAPR2 inhibition may be a better option in PARP targeting, in the context of HRD, clinical tolerance, and the basic biology of cancer progression [24]. All available PARPis (olaparib, rucaparib, talazoparib and niraparib) inhibit PARP1 and 2. Additionally, olaparib and rucaparib inhibit PARP 3 [25].

4 Role of PARP in Prostate Cancer (PCa) Biology

4.1 Role of PARP in Androgen Signalling

Androgen receptors (AR) in the cell nucleus modulate the expression of several genes, for example PSA and TMPRSS2, which are crucial for prostate biology [26]. Inhibition of androgen signalling is the mainstay of PCa therapy. ARs regulate transcription and translation via cooperation with over 150 co-repressors and co-stimulators, including GATA2, HOXB13 and NKX3, and some of these drive prostate carcinogenesis. FOXA1 is a protein that binds to chromatin and physically interacts with ARs and modulates AR transactivation. Overexpression of FOXA1 is associated with a poorer prognosis in patients with PCa [27]. PARP2, through interaction with FOXA1, enhances AR activity. The clinically relevant aspect of tumour PARP1 loss is a downregulation of nuclear androgen receptors. PARPs are one of the transcription regulators of AR and their inhibition decreases the expression of AR genes [28]. Genetic or pharmacological depletion of PARP2-FOXA1 interactions inhibits AR-mediated activity and tumour growth [28, 29]. In addition ARs promote the DNA damage response and regulate genes responsible for DDR, including for HR, NHEJ and MMR [20, 30, 31]. Antiandrogen therapy decreases expression of HR genes and ATM signalling.

4.2 Relationship Between PARP and the Tumour Microenvironment

Recently, the relationship between cancer and the tumour microenvironment has become a new issue in prostate pathobiology [32]. PARP affects reciprocal interactions between cells in the tumour microenvironment, affecting prostate tumorigenesis and its aggressiveness [17, 28, 33,34,35,36]. Immunohistochemical studies have shown that expression of PARP1 and PARP2 is higher in PCa than in benign tissue. Although PARP1 contributes to 90% of cellular activity, the expression of PARP2 correlates with biochemical recurrence in PCa [37]. PARP1 deficiency in the transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate (TRAMP) model led to the development of less differentiated tumours with a higher proliferative index compared to wild-type rodents. The driving mechanism involved TGF-β (transforming growth factor β)-dependent and Smad-regulated epithelial-mesenchymal transition [35, 38]. PARP modulates the development and growth of cancer by altering cancer-initiating cells, the immune response, angiogenesis, autophagy and the tumour hypoxic response. Preclinical studies on the tumour microenvironment show that, under hypoxia, expression of HRR genes is lower due to the activity of E2F transcription factors and histone methylation, which increases the sensitivity of tumour cells to PARPi [19, 21, 22, 39]. The hypoxic microenvironment increases the transcriptional activity of the AR and facilitates the development of castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), which correlates with HRR gene alterations [40, 41].

4.3 Relationship Between the PARP and E26 Transformation-Specific (ETS) System

The ETS (E26 transformation-specific family) is a family of transcription factors that regulate key cellular functions, like migration or proliferation of cells [42]. Gene rearrangements lead to increased activity of the ETS system, which enhances cancer growth and development. In turn, fusion between TMPRSS2 and ERG, which show functional similarity to ETS gene fusions, is present in around 50% of PCa cases and regulates key PCa biological functions [43,44,45].

Overexpression of ETS genes leads to DNA double-strand breaks. PARP and DNA-dependent protein kinase modulates transcriptomic activity of the ETS system. PARP1 also interacts with the androgen-receptor regulated TMPRSS2:ERG gene fusion protein. Olaparib has been shown to reduce the potential of invasion in ERG-positive PCa cell lines through inhibition of invasion-associated genes, for example, EZH2, which may provide new molecular therapeutic targets [43]. Despite promising results from preclinical studies, ETS stratification in clinical trials with abiraterone and veliparib did not confirm the clinical utility of ETS as a predictive factor [46]. Molecular stratification based on ETS status and PTEN expression in PCa may better predict clinical outcomes in localised and metastatic stages of disease [47, 48]. TMPRSS2-ERG-positive and PTEN-negative tumours are more sensitive to PARPi and radiation therapy [49].

5 Genetic Testing in PCa

5.1 The incidence of Genetic Alterations

The incidence of pathogenic somatic and germline mutations differs between localised and metastatic PCa (Table 2). In patients with primary PCa, the incidence of BRCA2 mutations in those under 65 years of age is low (1.2%), but at the CRPC stage this increases to 12% [50]. The incidence of germline BRCA1/2 or ATM mutations is higher in metastatic PCa than localised PCa [51]. An analysis of 3607 PCa patients revealed that 620 patients (17.2%) had pathogenic germline mutations. Importantly, the authors of the study highlighted that 37% of the tested patients did not meet the NCCN criteria for genetic consulting. The most common pathogenic mutations among entire cohorts were BRCA2 (4.74%), CHEK2 (2.88%) and ATM (2.03%). The prevalence of specific mutations among all patients with germline mutations was 24.3%, 14.1% and 9.6%, respectively, for BRCA2, CHEK2 and ATM [52]. The results are, in general, in accordance with the study by Pritchard et al., where germline mutations were identified in 11.8% of the cohort. The most common HRR gene alterations were BRCA2 (44%), ATM (13%), CHEK2 (12%), BRCA1 (7%), PALB2 (4%), RAD51D (4%), ATR (2%), NBN (2%), PMS2 (2%), GEN1 (2%) and MSH2, MSH6, RAD51C, MRE11A, BRIP1 and FAM175A (1% each) [50]. The non-BRCA proteins included DNA damage sensors (ATM, CHEK), DNA regulators (CDK12) or proteins that co-operate with the BRCA gene in the DNA repair process (FANCA, PALB2). Other components of the DDR system (e.g. ATR, CHEK1) are also being investigated as new therapeutic targets [53, 54].

Table 2 gives the incidence of germline and somatic mutations in localised and metastatic prostate cancer [13, 50, 55, 56].

5.2 Significance of BRCA Mutation in PCa

BRCA genes are considered the most clinically relevant genes of the tumour-predisposing genes in PCa. The standardised incidence for BRCA1 mutations is 2.35 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.43–3.88), compared to 4.45 for BRCA2 (95% CI 2.99–6.61) [57, 58]. A recently published meta-analysis clearly showed that PCa incidence is greater among BRCA mutation carriers, especially those with BRCA2 [5]. BRCA2 germline mutations increase the risk of PCa 8.6-fold by age 65 years [59]. The other germline mutations, like HOXB13 or ATM, are considered to be high-penetrance genes that increase the risk of PCa, but therapeutic and diagnostic values remain unclear [60]. The first analysis of the IMPACT trial suggested that patients aged 40–69 years with BRCA2 mutations may benefit from annual PSA testing [61]. PCa that develops in BRCAmut carriers displays different clinicopathological properties, occurring earlier and often with an intraductal or ductal histology with lymphovascular invasion. Moreover, the PCa in these patients often has a higher Gleason score or tumour stage. However, the results of this research are contraindicatory [62]. Due to the more aggressive course of disease, patients have a greater risk of progression after local treatment and a shorter cancer-specific survival, metastasis-free survival, and overall survival (OS). The significance and relevance of germline and somatic mutations other than in classical HR genes remains to be sufficiently elucidated. BRCA2 K3326* is a nonsense variant of the gene without a significant impact on DDR function [31]. Moreover, there are some doubts concerning the assessment of HRD status. Up to 8% of non-metastatic PCa patients may have HRD that is not derived from classical HRD (BRCA) and is associated with a PARPi response. This may be the result of CDH1 gene loss (encodes cadherin 1) or inactivation of the SPOP gene (encodes Speckle-type POZ protein), which are early events in cancer development [44, 63].

5.3 BRCAness

Some tumours, known as ‘BRCAness’, share phenotypic (phenocopies) and genetic properties with BRCA–mutated tumours, which partly depend on DNA repair of genetic defects. In other words, BRCAness can be defined as an error in DNA repair that is controlled by HRR. The BRCAness phenotype may be induced pharmacologically or due to genetic alterations in genes that modulate HRR, including ATM, ATR, CHEK1, RAD51, the Fanconi anaemia complementation group family of genes and others. New ideas for targeting BRCAness are the result of a better understanding of the function of BRCA proteins as replication fork protectors. BRCA1 and BRCA2 stabilise the RAD51 filament on the reversed replication forks, thereby protecting the open double-stranded end of the regressed arm. Meiotic recombination 11-Like (MRE11) is a nuclease that leads to the degradation of replication fork protection in the absence of BRCA proteins. In HRR, MRE11 forms a complex with RAD50 and NBS1 (Nijmegen breakage syndrome 1), which leads to ATM recruitment. In addition, checkpoint kinases, which regulate BRCA functions (ATR/CHK1, WEE1) and promote cycle progression (AURORA1 and its TPX2 cofactor, Polo-Like Kinase 1), contribute to BRCAness status and may be investigated in the future [64]. BRCAness induced by non-BRCA mutations is one of the most investigated issues associated with PARPi. Non-BRCA alterations were investigated in the TRITON2 study, and PSA and radiological responses in the non-BRCA group (ATM, CDK12, CHEK2) were limited, in contrast to patients with FANCA, PALB2, BRIP1 and RAD51B mutations [65]. However, there are doubts concerning BRCAness. Possible experimental biomarkers for BRCAness include the HRR gene alteration, functional assays of HRR capacity, and transcriptomic and mutational signatures [66].

5.4 Significance of Germline Testing in PCa

According to oncological guidelines, some patients with PCa should receive consultations with genetic specialists to diagnose families at higher risk of cancer development and choose appropriate therapeutic management. NCCN guidelines recommend germline testing for patients with high-risk or very high-risk PCa in all tumour stages, some families with a history of cancer, and specific populations of PCa patients who have an increased likelihood of PCa development, such as Ashkenazi Jews [67]. According to NCCN recommendations, germline panel testing using NGS should include BRCA2, BRCA1, ATM, CHEK2, PALB2, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2. DNA for germline testing can be obtained from lymphocytes or buccal cells [67].

5.5 Significance of Somatic Testing in PCa

Since registration of new targeted therapies that broaden the therapeutic landscape for PCa patients, a somatic (acquired) mutation test is recommended for every patient with metastatic PCa. In addition, positive results of genetic testing should lead to the referral of patients for genetic consulting. There are some doubts as to which material is the best for genetic testing. Metastatic sites may be better sources for detecting genetic alterations than tissue from the primary tumour due to their higher degree of genetic alterations as a result of heterogeneity and instability of the tumour genome. The highest frequency of mutations among HRD genes is present in brain and visceral metastases. It is recommended to repeat somatic mutation tests in cases of cancer progression [68]. Horak et al. described an interesting case of a 43-year-old patient with PCa with a PALB2 somatic mutation who was treated with cisplatin and PARPi. Upon liver progression, secondary genetic tests revealed possible mechanisms of drug resistance [69]. An alternative for new, repeated biopsies is the assessment of cell-free or circulating tumour cell DNA (ctDNA).

6 Clinical Aspects of PARP Inhibitors (PARPis)

6.1 Basics of PCa Treatment and PARPis

Since its discovery by Hoggins and Hodge, antiandrogen therapy has been the mainstay of metastatic prostate cancer therapy. Antiandrogens mediate multistep inhibition of signalling pathways in tumour cells and lead to an increased OS among PCa patients. Despite the initial effectiveness of this treatment, PCa transforms into an incurable, castration-resistant stage of disease due to ligand dependent and independent mechanisms that restore AR activity [70]. Currently available options for PCa patients consist of chemotherapy (docetaxel, cabazitaxel), molecularly directed, second-generation anti-androgens (abiraterone acetate, enzalutamide, apalutamide, darolutamide), radiopharmaceutical therapy (Radium-223), immunotherapy (sipuleucel-T, pembrolizumab) and PARPi (olaparib, rucaparib). A deeper understanding of the molecular and genetic landscape of PCa allows better stratification to old therapies, in addition to the design of new complex therapies [12, 67]. The OlympiAD, POLO and SOLO1 clinical trials determined PARPi efficacy in breast, pancreatic and ovarian cancer [71,72,73]. PARPis have opened up an era of genetically based targeted therapies in PCa and are a promising option. Many clinical trials are underway investigating different stages of PCa. The efficacy of PARPis is being evaluated in the localised, non-metastatic or disseminated stages of disease, independent of castration status. PARPis are being tested in monotherapy, polytherapy, with or without chemotherapy, targeted therapies, immunotherapy, radiation or prostatectomy (Table 3).

6.2 PARPi monotherapy

The first data about PARPi in patients with PCa came from a phase I study of 60 BRCAm patients treated with olaparib, among which 5% had CRPC, and one patient achieved > 50% PSA and radiological bone response [74].

The aim of the TOPARP studies was to evaluate PARPi effectiveness, identify the molecular pattern of PCa cells and look for predictive biomarkers. The first clinical data came from the open-label, single-arm TOPARP-A phase II study (Trial of Olaparib in Patients with Advanced Castrate Resistant Prostate Cancer). In the first part of the study, the activity of olaparib 400 mg twice daily was evaluated in genetically unselected patients with mCRPC. Initially, 50 patients were enrolled onto the study, but only 49 could be evaluated. All of the evaluated patients received docetaxel, 98% enzalutamide or abiraterone, and 58% cabazitaxel. The enrolled patients did not receive platinum-based regimens. The primary end-points were radiological response rate, a greater than 50% reduction in PSA, and a reduction in circulating tumour cells (CTC) from > 5 to < 5 cells per 7.5 mL of blood. Whole-exome sequencing and transcriptome studies were performed on fresh-frozen cores in tumour-biopsy samples obtained before treatment during screening. Germline targeted sequencing was performed on DNA from saliva samples. The copy number of the genes was validated with droplet digital polymerase-chain-reaction testing. In addition, tumour samples from biopsies performed before and during treatment were analysed. Biomarker-positive patients had a homozygous deletion or deleterious mutation in a gene involved in DNA repair or in sensitivity to PARP inhibition. Sixteen of the 49 patients (33%) had a response. In the second part of the study, a pre-planned biomarker analysis was performed in the sensitive group. Seven patients had BRCA2 loss (four with biallelic somatic loss and three with germline mutations), and five patients had an alteration in the ATM gene. Every patient with the BRCA2 mutation responded. Moreover, responses were observed in patients with somatic homozygous deletions of BRCA1 and FANCA, somatic frameshift mutations in PALB2, heterozygous PALB2 deletions, biallelic aberrations in HDAC2, and homozygous somatic deletions of BRCA1 or CHEK2 with FANCA deletion. The group of patients with BRCA1/2 and ATM mutations had an 88% response rate but there was no radiological response among ATM patients. Interestingly, patients with biallelic PALB2 mutation achieved a durable response and only two patients without DNA-repair gene alterations had a response (6%). Radiological progression-free survival (rPFS) and OS were longer in the biomarker-positive group than in those who were negative (rPFS: 9.8 vs. 2.7 months, P < 0.001; OS: 13.8 vs. 7.5 months, P = 0.05) [12].

The second open-label randomised TOPARP-B phase II trial was designed to confirm the previous results from the TOPARP-A study. Patients with metastatic PCa, pretreated with one to two lines of chemotherapy, were randomised to 400 mg or 300 mg olaparib twice daily. The patients were stratified according to DDR gene aberrations. The primary end-points were the same as in part A. Among patients who were assigned to 400 mg twice daily of olaparib, the composite response was achieved in 54.3% of patients (95% CI 39.0–69.1), the radiological response was achieved in 24.2% (95% CI 11.1–42.3), the PSA response in 37% (95% CI 23.2–52.5), and CTC conversion in 53.6% (95% CI 33.9–72.5). Patients who had BRCA1/2 mutations achieved the greatest composite overall response (83.3%; 95% CI 65.3–94.4) in comparison to PALB2 (57.1%; 95% CI 18.4–90.1), ATM (36.8%; 95% CI 16.3–61.6), CDK12 (25%, 95 CI 8.7–49.1), and other mutations (20%; 95% CI 5.7–43.7). The study confirmed the activity of PARPi in both germline and somatic mutations [75].

The initial results from the first phase of the PROFOUND III study were presented during the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) conference in 2019 [15]. The efficacy and safety of olaparib was compared with enzalutamide or abiraterone (as per the choice of the clinician) in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) who progressed onto new hormonal agents. Previous taxane therapy was allowed. Patients were eligible if they had any of the qualifying gene alterations. Patients were randomised 2:1 between cohort A (BRCA1, BRCA2, ATM) and B (BRIP1, BARD1, CDK12, CHEK1, CHEK2, FANCL, PALB2, PPP2R2A, RAD51B, RAD51C, RAD51D, RAD54L). The somatic mutation status was revealed in primary or metastatic sites with the FoundationOne CDx NGS test, and the tissue was either from the archive or newly obtained. The primary end-point was rPFS in cohort A. The secondary end-points were rPFS in cohort B and ORR, time to pain progression, and OS in cohort A. Patients were assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive olaparib or a drug chosen by the clinician (enzalutamide or abiraterone). Analysis revealed that olaparib significantly improved rPFS in cohort A (olaparib 7.4 months vs. 3.6 months (HR 0.34; 95% CI 0.25–0.47, P < 0.0001)) and B (olaparib 5.8 vs. 3.5 months (HR 0.49; 95% CI 0.38–0.63, P < 0.0001)). In addition, olaparib improved the objective response rate (ORR) (Cohort A: 33.3% for olaparib, B: 2.3% for enzalutamide/abiraterone). rPFS in the overall population (cohorts A and B) was prolonged (5.82 vs. 3.52 months (HR 0.49; 95% CI 0.38–0.63; P < 0.0001)). The median OS in cohort A was significantly longer (18.5 vs. 15.1 months) than in the hormonal therapy arm (HR 0.64; 95% CI 0.43–0.97, P = 0.02). Eighty-one percent of the patients who had progression in the control group received PARPi. The PROFOUND subgroup analysis and a retrospective review of 23 studies revealed that the benefit among patients with ATM alterations is weaker than in BRCA mutated patients [76]. ATR inhibitors and PARPis may be effective treatment strategies in ATM deficient PCa cell lines because in such cells olaparib acts cytostatically, not cytotoxically [77]. ATM loss sensitised cells to ATR kinase, which prevents genome instability in tumours and promotes tumour progression by enhancing Warburg effects [78].

In the TRITON2 study, mCRPC patients with a deleterious germline or somatic deleterious mutations in DDR genes (BRCA2, BRCA1, CDK12, CHEK2, FANCA, NBN, PALB2, RAD51, RAD51B, RAD51C, RAD51D, RAD54L) with disease progression on AR-directed therapy and one taxane-based chemotherapy, were treated with rucaparib 600 mg twice daily. The population included 115 patients with BRCA alterations (BRCA1 = 13; BRCA2 = 102; germline = 44, somatic = 71, measurable disease = 62). The confirmed ORR per modified RECTIST/Prostate Cancer Working Group 3 for patients with measurable disease and PSA response rate (≥ 50% decrease) for patients without measurable disease were the primary end-points. The ORR per independent radiology review was 43.5% (95% CI 31.0–56.7). A PSA response was seen in 54.8% (95% CI 45.2–64.1) of patients. ORRs in patients with germline/somatic BRCA1/2 alterations were similar, but higher PSA response rates were observed in patients with BRCA2 than BRCA1 alterations (59.8%; 95% CI 49.6–69.4 vs. 15.4%; 95% CI 1.9–45.4). Non-BRCA gene alterations were seen in 78 patients (ATM = 49, CDK12 = 15, CHEK2 = 12, other DDR = 14). ORR and PSA responses were reported in patients with non-BRCA gene alterations, as follows: ATM (10.5% vs. 4.1%), CDK12 (0% vs. 6.7%), CHEK2 (11.1% vs. 16.7%). Importantly, patients with PALB2, FANCA, BRIP1 and RAD51B mutations presented a response contrary to patients with germline or biallelic loss of ATM. In contrast to BRCA mutated tumours, the ORR and PSA responses in patients with ATM, CHEK2 and CDK12 mutations were low. The TRITON2 study, on the one hand, confirmed safety and efficacy in BRCA-mutated tumours, but on the other hand showed that there are no accurate biomarkers in non-BRCA-mutated tumours, which needs further investigation [65]. The results of the study led to FDA approval for rucaparib. The efficacy of rucaparib is currently being evaluated in the TRITON 3 (NCT02975934) phase III trial. Eligible mCRPC patients who experienced disease progression after one prior line of next generation AR-targeted therapy with BRCA1,2 or ATM deleterious mutations will be randomised to rucaparib or one of the standard therapies (abiraterone acetate, enzalutamide or docetaxel). Rucaparib is also being evaluated in non-metastatic hormone-naïve PCa with BRCAness (ROAR trial, NCT03533946) after prostatectomy and/or radiation therapy, with or without systemic therapy. The primary outcome measure is 50% reduction in PSA levels. BRCAness is defined as an alteration in any of the following genes: ATM, ATR, BARD1, BRCA1, BRCA2, BRIP1, CDK12, CHEK1, CHEK2, ERCC3, FAM175A, FANCA, FANCL, GEN1, HDAC2, MLH1, MRE11, NBN, PALB2, PPP2R2A, RAD51 or RAD54L. Mutations are tested by soft-tissue based genomic testing or liquid biopsy-based genomic or genetic testing.

In contrast to the previously described studies, the DDR status among patients for the ongoing phase II, single-arm GALAHAD study is being evaluated with a plasma or tissue gene panel (BRCA1/2, ATM, FANCA, PALB2, CHEK2, BRIP1, HDAC2). The study was designed to determine the safety and efficacy of niraparib among mCRPC patients who progressed on taxane-based chemotherapy and AR-targeted therapy. The primary end-point was ORR by RECIST 1.1/PCWG3 criteria and composite response rate (CRR) conversion of circulating tumour cells to < 5/7.5 mL blood, or ≥ 50% decline in PSA. The preliminary results of the study presented during ESMO 2019 showed that biallelic DDR defects in BRCA (46 patients) were associated with a higher ORR 41% (95% CI 23.5–61.1) than non-BRCA (35 patients) 9% (95% CI 1.1–29.2). In addition, patients with BRCA1/2 biallelic DRD in comparison to non-BRCA gene alterations achieved a greater PSA response (50%; 95% CI 34.9–65.1 vs. 3%; 95% CI 0.1–14.9), CTC conversion (47; 95% CI 31.0–64.2 vs. 21; 95% CI 7.1–42.2), CRR (63%; 95% CI 47.6–76.8 vs. 17%; 95% CI 6.6–33.7), median rPFS (8.2; 95% CI 5.2–11.1 vs. 5.3 months; 95% CI 1.9–5.7) and median OS (12.6; 95% CI 9.2–15.7 vs. 14.0 months; 95% CI 5.3–20.1) [79]. The results will be confirmed in the MAGNITUDE (NCT03748641) phase III randomised, placebo-controlled study. The comparator for niraparib is abiraterone with prednisone.

TALAPRO-1 is a phase II study in men with mCRPC and DDR mutation (ATM, ATR, BRCA1/2, CHEK2, FANCA, MLH1, MRE11A, NBN, PALB2 or RAD51C). Enrolled patients received one to two chemotherapy regimens (one or more taxane based) and novel hormone therapy (enzalutamide or abiraterone). The primary end-point is ORR. The secondary end-points are time to response and its duration, PSA decrease ≥ 50%, time to PSA progression, CTC count conversion, rPFS, OS, and safety. The initial results of the interim analysis were presented during the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) meeting in 2020. The results of the study show that talazoparib presented the strongest activity measured as a composite response (OR and/or PSA response ≥ 50% and/or CTC conversion) in BRCA1/2 tumours (76.1%); however, the response in ATM (50%) and PALB2 (27.8%) patients was also promising [80].

In preclinical tumour models, veliparib potentiated the activity of DNA-damaging agents like temozolomide, cisplatin, carboplatin and also radiation [81]. It was suggested that veliparib can overcome temozolomide resistance in PCa cell lines and that this combination increased the survival of mice in comparison to temozolomide monotherapy [82]. Veliparib maintenance after carboplatin-based chemotherapy regimens in metastatic BRCA2 mutated ERG positive CRPC led to a durable complete response with a good toxicity profile [83]. The clinical utility of veliparib was evaluated in a phase II study. Patients were stratified according to ETS status and randomised to the following arms: abiraterone, with or without veliparib. ETS fusion failed to be a predictive factor [84]. The results of this study were negative; however, a subgroup of patients with DDR achieved a higher PSA rate, PSA decline ≥ 90% and a median PFS that was 6.4 months longer. There have been no phase III clinical trials with veliparib to date.

PARPi in monotherapy is currently being evaluated in the neoadiuvant setting and in non-metastatic CSPC. Patients with high-risk, localised PCa with DNA alterations in the repair pathway will receive three cycles of niraparib (NCT04030559) or olaparib (BrUOG 337B, NCT 03,432,897) before prostatectomy. In the NCT03047135 trial, olaparib is being tested in high-risk, non-metastatic, biochemically recurrent PCa after prostatectomy. An analysis of biomarkers will be performed. In addition to the known drugs, newly designed PARPis are being investigated as a treatment option in phase I trials in advanced and metastatic solid tumours (NCT04182516, NMS-03305293; NCT03508011, IMP 4297-Senaparib). Pamiparib is a selective PARP1/2 inhibitor with a capability to penetrate the brain. Presently, it is being tested in a phase II trial in mCRPC positive for CTC with HRD (NCT03712930).

6.3 PARPis in Combination Therapy

After the promising results of PARPis in monotherapy, they are now being tested with drugs which, in recent years, have significantly broadened the treatment options for PCa patients, like novel antiandrogens, chemotherapy, radiopharmaceuticals and immunotherapy. The aim of combination therapy is to extend the population of patients who will benefit, especially in the group without DDR alteration.

Abiraterone and enzalutamide are second-generation AR axis-targeted therapies that decrease AR signalling, and increase OS in hormone-sensitive and -resistant PCa. The reciprocal relationship between AR signalling and PARP supports the development of combinational strategies. PARPi may enhance the potency of AR-targeted therapies, because PARP1 modulates interactions between chromatin and AR [28, 85]. The efficacy of both drugs was evaluated in combination with PARPi in a phase II, randomised, placebo-controlled trial that compared abiraterone with or without olaparib. Abiraterone was seen to inhibit androgen synthesis by inhibition of CYP17 steroidogenesis enzymes. Irrespective of HRR status, combination therapy increased the median rPFS by 5.6 months, and may be considered as a new type of synthetic lethality [86]. Enzalutamide is a second-generation antiandrogen that inhibits key stages of AR signalling. Preclinical research shows that PARPi and enzalutamide change the expression of apoptosis-related signalling pathways, and the most promising therapeutic strategy is enzalutamide following enzalutamide and olaparib therapy [87]. In 2018, Clarke et al. published the results of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II trial that provided clinical efficacy of combining therapy for patients with mCRPC who received docetaxel and were candidates for abiraterone treatment. Patients (n = 142) were randomly assigned to olaparib + abiraterone or placebo + abiraterone arms. Median rPFS was significantly longer in the abiraterone plus olaparib group than in the abiraterone plus placebo group (13.8 vs. 8.2 months; HR 0.65; 95% CI 0.44–0.97, P = 0.034), and this was independent of genetic status. The study BRCAAway is an ongoing randomised phase II trial in mCRPC with DNA repair defects (loss of ATM, BRCA1, BRCA2). Patients who want to take part in the study will have to provide new material for biopsy. Enrolled patients are randomised to abiraterone + prednisone (arm I), olaparib (arm II), or abiraterone + prednisone and olaparib (arm III). If patients have non-canonical DNA-repair gene alterations, they will receive olaparib in monotherapy. Patients in olaparib or abiraterone arms may cross over to the combination therapy arm at progression. The primary end-point is radiographical and clinical PFS. The secondary end-points are objective disease and PSA response rates. PROpel is the first phase III trial (NCT03732820) designed to compare abiraterone + placebo to abiraterone + olaparib in patients with BRCA1,2 or ATM mutations with progressive mCRPC in the first-line setting of mCRPC. The aim of the TALAPRO-2 phase III trial (NCT03395197) is to compare rPFS in patients with asymptomatic or minimally asymptomatic patients with mCRPC treated with talazoparib or talazoparib with enzalutamide. Part I of the study determined the starting dose for talazoparib. Part II of the study will evaluate the efficacy, safety and pharmacokinetics of combination therapy. Patients are stratified by prior treatment and DDR mutation status.

An interesting proposal is combining PARPi with immunotherapy (anti PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors). PARP increases the tumoral immunogenicity by accumulation of neoantigens, epigenetic changes, and affecting the immune response and tumour microenvironment, which explains the possibility of increasing the efficacy of anti-PD-1/L1 inhibitors. The Keynote-365 phase Ib/II trial showed that median radiographic rPFS for pembrolizumab and olaparib was 4.3 months, and median overall survival (OS) was 14 months [88]. The Keylink-010 study (NCT03834519) with olaparib and pembrolizumab is designed to test if combinations of these drugs increase OS and rPFS. Unselected patients enrolled into the study were pre-treated with enzalutamide/abiraterone and chemotherapy. The comparator will be a next-generation hormonal agent. Another phase II study is underway with durvalumab and olaparib for patients with biochemically recurrent (PSA double time < 9 months), non-metastatic CSPC with DDR mutations (NCT03810105). In addition, a phase Ib/II trial of anti PD-L1 avelumab and talazoparib will be tested to assess dose-limiting toxicity and overall response in patients with locally advanced, metastatic solid tumours, including CRPC (NCT03330405).

Docetaxel is an old chemotherapeutic agent that is currently used in castration-sensitive and CRPC patients. Patients with mCRPC with homologous HRR DNA deficiency (BRCA2, BRCA1, ATM, PALB2) will be enrolled in the PLATI-PARP study to receive four cycles of docetaxel and a carboplatin chemotherapy regimen, with rucaparib as a maintenance therapy (NCT03442556, PLATI-PARP).

In addition, there are clinical data that show that patients with BRCAmut are better responders to radiation therapy and, surprisingly, Radium-223 therapy [89]. The ASCLEPlus trial (NCT04194554) is a phase I/II trial that will be evaluating dose-limiting toxicities and the proportion of patients experiencing biochemical failure. The inclusion criteria include node-positive PCa and/or high-risk PCa. Patients will receive niraparib, leuprolide, abiraterone, and stereotactic body radiotherapy at a total dose of 37.5–40 Gy. The ongoing clinical trials with radioligands include the combination of olaparib or niraparib with radium-223 in mCRPC (COMRADE, NCT03317392; NiraRAD, NCT03076203). 177 Lu-PSMA is a new innovative radioligand that demonstrates activity in heavily pretreated PCa. The LuPARP study is a phase I dose-escalation and dose-expansion study that will evaluate the safety and tolerability of olaparib in combination with 177Lu-PSMA (NCT03874884). A new concept in therapy includes combining PARPi with ATR inhibitor (AZD 6738, NCT03787680) or antiangiogenic drugs like cediranib (NCT02893917). ATR is a kinase of DNA damage response and modulates the ATR checkpoint kinase 1 signalling pathway [90]. Cediranib is an orally active, small molecule inhibitor of VEGFR (vascular endothelial growth factor receptor).

6.4 PARPi Toxicity

Compared to chemotherapy, the toxicity of PARP inhibitors is low; however, there is a lack of mature data about the long-term safety of PARPi in PCa populations. According to the PROFOUND trial, the most common adverse events were haematological (anaemia 46%), gastrointestinal (nausea 41%, loss of appetite 30%) and fatigue or asthenia (41%). Twenty-two percent of the patients required dose reduction due to adverse events [76]. The GALAHAD and TRITON2 studies confirmed data from previous studies, with the most common adverse event being anaemia (17.9–25%) [65, 79]. It is important to remain aware of patients who received Radium-223 or taxane chemotherapy regimens, as these patients may be more prone to developing myelosuppression during PARPi therapy. Anaemia remains the most common grade 3 toxicity adverse event [76]. In the PROFOUND trial, myelodysplastic syndrome was not reported, despite initial reports and published case reports [91]. A recently published meta-analysis of 14 trials showed that PARPi in combined therapy may be associated with myelodysplastic syndrome, but the incidence of that complication is low [92].

7 Conclusions

Androgen-deprivation therapy is the mainstay of treatment for metastatic PCa. Despite the initial responsiveness to androgen-deprivation therapy, PCa transforms into an incurable castration-resistant stage of the disease. During cancerogenesis and the development of castration resistance the genomic landscape of PCa changes. DNA-repair pathway mutations are one of the classes of clinically actionable mutations that occur more frequently in CRPC than primary PCa [13].

Approximately 20% of CRCP patients harbour germline or somatic mutations in one of the HRR genes, which supports the mechanism of synthetic lethality. PARP inhibitors are the first registered treatment options for patients with mCRPC based on the genetic concept of synthetic lethality. The FDA has approved olaparib in HRR-mutated and rucaparib in BRCA-mutated mCRPC. PARPis should be considered in patients who have HRR mutations and have progressed on enzalutamide and/or abiraterone, regardless of prior docetaxel therapy. The main doubts concerning PARPi include proper genetic analysis and its clinical relevance. In the majority of clinical trials, the stratification to treatment arms depends on the HRR status. Genetic testing (next-generation sequencing) should be performed, optimally, in fresh collected tumour biopsies, because of the highest rate of detected mutations. Less optimal sources for genetic testing are circulating tumour DNA, primary tumour tissue, and blood or saliva samples. There are some doubts concerning the sensitivity of drugs in relationship to specific genetic mechanisms leading to gene alterations. It is not yet clear which patients achieve the greatest benefit. The meta-analysis by Mohyuddin et al. indicates that the response rates and survival for patients with somatic and germline mutations are similar [93]. There is a suggestion that patients with biallelic BRCA2 inactivation achieved the greatest benefit in comparison to non-BRCA mutated patients. Results from the TOPARP-B and TRITON-2 studies suggest that patients with ATM alteration achieved much less benefit than those with BRCA altered tumours [14, 75].

Many clinical trials are ongoing to determine the efficacy of PARPi monotherapy, polytherapy at different tumour stages and independent of the castration status of the PCa. The strongest clinical data indicate the use of PARPis in castration resistant phases of disease, however, ongoing trials may change the indications for PARPi in castration-sensitive PCa, similar to docetaxel or novel antiandrogens. The data from preclinical and clinical trials support the use of PARPis in combination therapy.

PARPis are not the only new genomically defined pharmaceuticals. Immunotherapy has significantly changed the way many cancers are managed; however, in PCa the use of immunotherapy remains low. Pembolizumab was the first anti-PD1-directed therapy registered by the FDA for PCa with MMR deficiency (MSH2, MSH6, MLH2 or PMS2) or microsatellite instability (MSI). There is a need to clarify the biomarkers of immune responsiveness and DNA damage repair to indicate the appropriate guidelines [94]. PARPi and anti PD-1 therapy are approved therapies by NCCN, however, with a higher level of evidence for olaparib (category 1) than pembrolizumab (category 2B) [95].The results of clinical trial data regarding OS are immature, although heavily pretreated patients who receive PARPi have a 66% lower risk of progression or death [76]. PARPis are breakthrough therapies in oncology and key components of a new era of targeted therapies and molecular tumour boards [96]. Important issues that remain are the determination of prognostic and predictive factors to facilitate personalised therapy to achieve more effective results from treatment.

References

Wallis CJD, Nam RK. Prostate cancer genetics: a review. EJIFCC. Int Fed Clin Chem Lab Med. 2015;26:79–91.

Wang G, Zhao D, Spring DJ, Depinho RA. Genetics and biology of prostate cancer. Genes Dev. 2018;32:1105–40.

Mottet N, van den Bergh RC., Briers E, Cornford P, De Santis M, Fanti S. EAU Guidelines: Prostate Cancer | Uroweb. EAU Guidel. Edn. In: Present. EAU Annu. Congr. Barcelona 2019. 2020.

Hemminki K. Familial risk and familial survival in prostate cancer. World J Urol. 2012;30:143–8.

Oh M, Alkhushaym N, Fallatah S, Althagafi A, Aljadeed R, Alsowaida Y, et al. The association of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations with prostate cancer risk, frequency, and mortality: a meta-analysis. Prostate. 2019;79:880–95.

Castro E, Eeles R. The role of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in prostate cancer. Asian J Androl. 2012;68:409–14.

Chatterjee N, Walker GC. Mechanisms of DNA damage, repair, and mutagenesis. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2017;58:235–63.

Roy R, Chun J, Powell SN. BRCA1 and BRCA2: Different roles in a common pathway of genome protection. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012; p. 68–78.

Farmer H, McCabe H, Lord CJ, Tutt AHJ, Johnson DA, Richardson TB, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434:917–21.

Fouad YA, Aanei C. Revisiting the hallmarks of cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 2017;7:1016–36.

Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74.

Mateo J, Carreira S, Sandhu S, Miranda S, Mossop H, Perez-Lopez R, et al. DNA-repair defects and olaparib in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1697–708.

Robinson D, Van Allen EM, Wu YM, Schultz N, Lonigro RJ, Mosquera JM, et al. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell. 2015;161:1215–28.

Abida W, Bryce AH, Balar AV, Chatta GS, Dawson NA, Guancial EA, et al. TRITON2: an international, multicenter, open-label, phase II study of the PARP inhibitor rucaparib in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) associated with homologous recombination deficiency (HRD). J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:TPS388.

Fizazi K, Maillard A, Penel N, Baciarello G, Allouache D, Daugaard G, et al. A phase III trial of empiric chemotherapy with cisplatin and gemcitabine or systemic treatment tailored by molecular gene expression analysis in patients with carcinomas of an unknown primary (CUP) site (GEFCAPI 04). Ann Oncol. 2019;30:v851.

Wright WD, Shah SS, Heyer WD. Homologous recombination and the repair of DNA double-strand breaks. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:10524–35.

Morales JC, Li L, Fattah FJ, Dong Y, Bey EA, Patel M, et al. Review of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) mechanisms of action and rationale for targeting in cancer and other diseases. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2014;24:15–28.

O’Connor MJ. Targeting the DNA damage response in cancer. Mol Cell. 2015;60:547–60.

Pezaro C. PARP inhibitor combinations in prostate cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2020;12:1–10.

Asim M, Tarish F, Zecchini HI, Sanjiv K, Gelali E, Massie CE, et al. Synthetic lethality between androgen receptor signalling and the PARP pathway in prostate cancer. Nat Commun. 2017;8:394.

Yar MS, Haider K, Gohel V, Siddiqui NA, Kamal A. Synthetic lethality on drug discovery: an update on cancer therapy. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2020; p. 823–32.

Chan N, Pires IM, Bencokova Z, Coackley C, Luoto KR, Bhogal N, et al. Contextual synthetic lethality of cancer cell kill based on the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8045–54.

Veskimäe K, Staff S, Grönholm A, Pesu M, Laaksonen M, Nykter M, et al. Assessment of PARP protein expression in epithelial ovarian cancer by ELISA pharmacodynamic assay and immunohistochemistry. Tumor Biol S. 2016;37:11991–9.

Gui B, Gui F, Takai T, Feng C, Bai X, Fazli L, et al. Selective targeting of PARP-2 inhibits androgen receptor signaling and prostate cancer growth through disruption of FOXA1 function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:14573–82.

Min A, Im SA. PARP inhibitors as therapeutics: beyond modulation of parylation. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(2):394.

Fujita K, Nonomura N. Role of androgen receptor in prostate cancer: a review. World J Mens Heal. 2019;37:288–95.

Gerhardt J, Montani M, Wild P, Beer M, Huber F, Hermanns T, et al. FOXA1 promotes tumor progression in prostate cancer and represents a novel hallmark of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:848–61.

Schiewer MJ, Goodwin JF, Han S, Chad Brenner J, Augello MA, Dean JL, et al. Dual roles of PARP-1 promote cancer growth and progression. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:1134–49.

Adamo P, Ladomery MR. The oncogene ERG: a key factor in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2016;35:403–14.

Haffner MC, Aryee MJ, Toubaji A, Esopi DM, Albadine R, Gurel B, et al. Androgen-induced TOP2B-mediated double-strand breaks and prostate cancer gene rearrangements. Nat Genet. 2010;42:668–75.

Arce S, Athie A, Pritchard CC, Mateo J. Germline and somatic defects in DNA repair pathways in prostate cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1210:279–300.

Sejda A, Sigorski D, Gulczyński J, Wesołowski W, Kitlińska J, Iżycka-Świeszewska E. Complexity of neural component of tumor microenvironment in prostate cancer. Pathobiology. 2020;87:87–99.

Horvath EM, Zsengellér ZK, Szabo C. Quantification of PARP activity in human tissues: Ex Vivo assays in blood cells and immunohistochemistry in human biopsies. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;780:267–75.

Weaver AN, Yang ES. Beyond DNA repair: additional functions of PARP-1 in cancer. Front Oncol. 2013;3:290.

Pu H, Horbinski C, Hensley PJ, Matuszak EA, Atkinson T, Kyprianou N. PARP-1 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in prostate tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35:2592–601.

Barboro P, Ferrari N, Capaia M, Petretto A, Salvi S, Boccardo S, et al. Expression of nuclear matrix proteins binding matrix attachment regions in prostate cancer. PARP-1: new player in tumor progression. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:1574–86.

Salemi M, Galia A, Fraggetta F, La Corte C, Pepe P, La Vignera S, et al. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 protein expression in normal and neoplastic prostatic tissue. Eur J Histochem. 2013;57:80–2.

Martí JM, Fernández-Cortés M, Serrano-Sáenz S, Zamudio-Martinez E, Delgado-Bellido D, Garcia-Diaz A, et al. The multifactorial role of PARP-1 in tumor microenvironment. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(3):739.

Bindra RS, Gibson SL, Meng A, Westermark U, Jasin M, Pierce AJ, et al. Hypoxia-induced down-regulation of BRCA1 expression by E2Fs. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11597–604.

Ming L, Byrne NM, Camac SN, Mitchell CA, Ward C, Waugh DJ, et al. Androgen deprivation results in time-dependent hypoxia in LNCaP prostate tumours: Informed scheduling of the bioreductive drug AQ4N improves treatment response. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:1323–32.

Stewart GD, Ross JA, McLaren DB, Parker CC, Habib FK, Riddick ACP. The relevance of a hypoxic tumour microenvironment in prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2010;105:8–13.

Sizemore GM, Pitarresi JR, Balakrishnan S, Ostrowski MC. The ETS family of oncogenic transcription factors in solid tumours. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:337–51.

Brenner JC, Ateeq B, Li Y, Yocum AK, Cao Q, Asangani IA, et al. Mechanistic rationale for inhibition of Poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase in ETS gene fusion-positive prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:664–78.

Testa U, Castelli G, Pelosi E. Cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying prostate cancer development: therapeutic implications. Medicines. 2019;6:82.

Abdel-Hady A, El-Hindawi A, Hammam O, Khalil H, Diab S, El-Aziz SA, et al. Expression of ERG protein and TMRPSS2-ERG fusion in prostatic carcinoma in egyptian patients. Open access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5:147–54.

Hussain M, Carducci MA, Slovin S, Cetnar J, Qian J, McKeegan EM, et al. Targeting DNA repair with combination veliparib (ABT-888) and temozolomide in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2014;32:904–12.

Lahdensuo K, Erickson A, Saarinen I, Seikkula H, Lundin J, Lundin M, et al. Loss of PTEN expression in ERG-negative prostate cancer predicts secondary therapies and leads to shorter disease-specific survival time after radical prostatectomy. Mod Pathol. 2016;29:1565–74.

Baumgartner E, del Pena CRM, Eich ML, Porter KK, Nix JW, Rais-Bahrami S, et al. PTEN and ERG detection in multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging/ultrasound fusion targeted prostate biopsy compared to systematic biopsy. Hum Pathol. 2019;90:20–6.

Chatterjee P, Choudhary GS, Sharma A, Singh K, Heston WD, Ciezki J, et al. PARP inhibition sensitizes to low dose-rate radiation TMPRSS2-ERG fusion gene-expressing and PTEN-deficient prostate cancer cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60408.

Pritchard CC, Mateo J, Walsh MF, De Sarkar N, Abida W, Beltran H, et al. Inherited DNA-repair gene mutations in men with metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:443–53.

Na R, Zheng SL, Han M, Yu H, Jiang D, Shah S, et al. Germline mutations in ATM and BRCA1/2 distinguish risk for lethal and indolent prostate cancer and are associated with early age at death. Eur Urol. 2017;71:740–7.

Nicolosi P, Ledet E, Yang S, Michalski S, Freschi B, O’Leary E, et al. Prevalence of germline variants in prostate cancer and implications for current genetic testing guidelines. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:523–8.

Reaper PM, Griffiths MR, Long JM, Charrier JD, MacCormick S, Charlton PA, et al. Selective killing of ATM- or p53-deficient cancer cells through inhibition of ATR. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:428–30.

Landau HJ, McNeely SC, Nair JS, Comenzo RL, Asai T, Friedman H, et al. The checkpoint kinase inhibitor AZD7762 potentiates chemotherapy-induced apoptosis of p53-mutated multiple myeloma cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:1781–8.

Abeshouse A, Ahn J, Akbani R, Ally A, Amin S, Andry CD, et al. The molecular taxonomy of primary prostate cancer. Cell. 2015;163:1011–25.

Quigley DA, Dang HX, Zhao SG, Lloyd P, Aggarwal R, Alumkal JJ, et al. Genomic hallmarks and structural variation in metastatic prostate cancer. Cell. 2018;174(758–769):e9.

Leongamornlert D, Mahmud N, Tymrakiewicz M, Saunders E, Dadaev T, Castro E, et al. Germline BRCA1 mutations increase prostate cancer risk. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1697–701.

Nyberg T, Frost D, Barrowdale D, Evans DG, Bancroft E, Adlard J, et al. Prostate cancer risks for male BRCA1[Formula presented] and BRCA2 mutation carriers: a prospective cohort study. Eur Urol. 2020;77:24–35.

Kote-Jarai Z, Leongamornlert D, Saunders E, Tymrakiewicz M, Castro E, Mahmud N, et al. BRCA2 is a moderate penetrance gene contributing to young-onset prostate cancer: Implications for genetic testing in prostate cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:1230–4.

Xu J, Labbate CV, Isaacs WB, Helfand BT. Inherited risk assessment of prostate cancer: it takes three to do it right. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2020;66:59–61.

Page EC, Bancroft EK, Brook MN, Assel M, Al Battat HM, Thomas S, et al. Interim results from the IMPACT study: evidence for prostate-specific antigen screening in BRCA2 mutation carriers. Eur Urol. 2019;76:831–42.

Isaacsson Velho P, Antonarakis ES. PD-1/PD-L1 pathway inhibitors in advanced prostate cancer. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2018;11:475–86.

Sztupinszki Z, Diossy M, Krzystanek M, Borcsok J, Pomerantz MM, Tisza V, et al. Detection of molecular signatures of homologous recombination deficiency in prostate cancer with or without BRCA1/2 mutations. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:2673–80.

Byrum AK, Vindigni A, Mosammaparast N. Defining and modulating ‘BRCAness’. Trends Cell Biol. 2019;29:740–51.

Abida W, Campbell D, Patnaik A, Shapiro JD, Sautois B, Vogelzang NJ, et al. Non-BRCA DNA damage repair gene alterations and response to the PARP inhibitor rucaparib in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: analysis from the phase II TRITON2 study. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:2487–96.

Lord CJ, Ashworth A. BRCAness revisited. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:110–20.

Schaeffer E, Srinivas S, Antonarakis ES, Armstrong AJ, Bekelman JE, Cheng H, et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Prostate Cancer. Version 2. 2020.

Dall’Era MA, McPherson JD, Gao AC, DeVere White RW, Gregg JP, Lara PN. Germline and somatic DNA repair gene alterations in prostate cancer. Cancer. 2020;126:2980–5.

Horak P, Weischenfeldt J, Von Amsberg G, Beyer B, Schütte A, Uhrig S, et al. Response to olaparib in a PALB2 germline mutated prostate cancer and genetic events associated with resistance. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2019;5:a003657.

Dutt SS, Gao AC. Molecular mechanisms of castration-resistant prostate cancer progression. Future Oncol. 2009;5:1403–13.

Robson ME, Tung N, Conte P, Im SA, Senkus E, Xu B, et al. OlympiAD final overall survival and tolerability results: Olaparib versus chemotherapy treatment of physician’s choice in patients with a germline BRCA mutation and HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:558–66.

Golan T, Hammel P, Reni M, Van Cutsem E, Macarulla T, Hall MJ, et al. Maintenance olaparib for germline BRCA-mutated metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:317–27.

Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G, Kim BG, Oaknin A, Friedlander M, et al. Maintenance olaparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2495–505.

Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, Tutt A, Wu P, Mergui-Roelvink M, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:123–34.

Mateo J, Porta N, Bianchini D, McGovern U, Elliott T, Jones R, et al. Olaparib in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with DNA repair gene aberrations (TOPARP-B): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:162–74.

De Bono J, Mateo J, Fizazi K, Saad F, Shore N, Sandhu S, et al. Olaparib for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2091–102.

James ND, Sydes MR, Clarke NW, Mason MD, Dearnaley DP, Spears MR, et al. Addition of docetaxel, zoledronic acid, or both to fi rst-line long-term hormone therapy in prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): survival results from an adaptive, multiarm, multistage, platform randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1163–77.

Xu L, Ma E, Zeng T, Zhao R, Tao Y, Chen X, et al. ATM deficiency promotes progression of CRPC by enhancing Warburg effect. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2019;26:59–71.

Smith MR, Sandhu SK, Kelly WK, Scher HI, Efstathiou E, Lara P, et al. Phase II study of niraparib in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) and biallelic DNA-repair gene defects (DRD): Preliminary results of GALAHAD. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:202–202.

De Bono JS, Mehra N, Higano CS, Saad F, Buttigliero C, Mata M, et al. TALAPRO-1: A phase II study of talazoparib (TALA) in men with DNA damage repair mutations (DDRmut) and metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC)—first interim analysis (IA). J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:119–119.

Donawho CK, Luo Y, Luo Y, Penning TD, Bauch JL, Bouska JJ, et al. ABT-888, an orally active poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor that potentiates DNA-damaging agents in preclinical tumor models. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2728–37.

Palma JP, Wang YC, Rodriguez LE, Montgomery D, Ellis PA, Bukofzer G, et al. ABT-888 confers broad in vivo activity in combination with temozolomide in diverse tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:7277–90.

Van der Weele DJ, Paner GP, Fleming GF, Szmulewitz RZ. Sustained complete response to cytotoxic therapy and the PARP inhibitor veliparib in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer—a case report. Front Oncol. 2015;5:169.

Hussain M, Daignault-Newton S, Twardowski PW, Albany C, Stein MN, Kunju LP, et al. Targeting androgen receptor and DNA repair in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: Results from NCI 9012. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:991–9.

Reddy V, Wu M, Ciavattone N, McKenty N, Menon M, Barrack ER, et al. ATM inhibition potentiates death of androgen receptor-inactivated prostate cancer cells with telomere dysfunction. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:25522–33.

Clarke N, Wiechno P, Alekseev B, Sala N, Jones R, Kocak I, et al. Olaparib combined with abiraterone in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:975–86.

Li L, Karanika S, Yang G, Wang J, Park S, Broom BM, et al. Androgen receptor inhibitor-induced “BRCAness” and PARP inhibition are synthetically lethal for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Sci Signal. 2017;10:eaam7479.

Yu EY, Massard C, Retz M, Tafreshi A, Carles Galceran J, Hammerer P, et al. Keynote-365 cohort a: Pembrolizumab (pembro) plus olaparib in docetaxel-pretreated patients (pts) with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:145–145.

Steinberger AE, Cotogno P, Ledet EM, Lewis B, Sartor O. Exceptional duration of radium-223 in prostate cancer with a BRCA2 mutation. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2017;15:e69–71.

Maréchal A, Zou L. DNA damage sensing by the ATM and ATR kinases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a012716–a012716012716.

Sari M, Saip P. Myelodysplastic syndrome after olaparib treatment in heavily pretreated ovarian carcinoma. Am J Ther. 2019;26:e632–e633633.

Nitecki R, Gockley AA, Floyd JL, Coleman RL, Melamed A, Rauh-Hain JA. The incidence of myelodysplastic syndrome in patients receiving poly-ADP ribose polymerase inhibitors for treatment of solid tumors: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:3641–3641.

Mohyuddin GR, Aziz M, Britt A, Wade L, Sun W, Baranda J, et al. Similar response rates and survival with PARP inhibitors for patients with solid tumors harboring somatic versus Germline BRCA mutations: a meta-analysis and systematic review. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:507.

Vikas P, Borcherding N, Chennamadhavuni A, Garje R. Therapeutic potential of combining PARP inhibitor and immunotherapy in solid tumors. Front Oncol. 2020;10:570.

Mohler JL, Antonarakis ES, Armstrong AJ, D’Amico AV, Davis BJ, Dorff T, et al. Prostate cancer, version 2.2019. JNCCN J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2019;17:479–505.

Julka PK, Verma A, Gupta K. Personalized treatment approach to metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with BRCA2 and PTEN mutations: a case report. Case Rep Oncol. 2020;13:55–61.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn.

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

Dawid Sigorski, Ewa Iżycka-Świeszewska and Lubomir Bodnar declare that they have no conflicts of interest that might be relevant to the contents of this article.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Idea for the article, literature search and data analysis were performed by DS, EI-Ś. The first draft of the manuscript was written by DS and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. L.Bodnar and EI-Ś critically revised the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sigorski, D., Iżycka-Świeszewska, E. & Bodnar, L. Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerase Inhibitors in Prostate Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms, and Preclinical and Clinical Data. Targ Oncol 15, 709–722 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11523-020-00756-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11523-020-00756-4