Abstract

Properties of plasmonic materials are associated with surface plasmons—the electromagnetic excitations coupled to coherent electron charge density oscillations on a metal/dielectric interface. Although decay of such oscillations cannot be avoided, there are prospects for controlling plasmon damping dynamics. In spherical metal nanoparticles (MNPs), the basic properties of localized surface plasmons (LSPs) can be controlled with their radius. The present paper handles the link between the size-dependent description of LSP properties derived from the dispersion relation based on Maxwell’s equations and the quantum picture in which MNPs are treated as “quasi-particles.” Such picture, based on the reduced density matrix of quantum open systems ruled by the master equation in the Lindblad form, enables to distinguish between damping processes of populations and coherences of multipolar plasmon oscillatory states and to establish the intrinsic relations between the rates of these processes, independently of the size of MNP. The impact of the radiative and the nonradiative energy dissipation channels is discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Plasmonics is a promising research area with many potential applications ranging from photonics, chemistry, medicine, bioscience, energy harvesting, and communication to information processing (e.g., [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]) and quantum optics (e.g., [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]). Plasmonics is based on the excitation of plasmons—electromagnetic excitations coupled to electron charge density oscillations on metal-dielectric interfaces, which result in confinement and enhancement of electromagnetic (EM) fields at metal/dielectric interfaces.

The optical features of metal nanoparticles (MNPs) are dominated by their ability to resonate with the EM radiation. Excitation of collective surface charge oscillations in form of the standing waves known as localized surface plasmons (LSPs) gives rise to a variety of effects such as the near-field concentration to the region well below the diffraction limit or the far-field resonant absorption and scattering in the spectral ranges which can be manipulated by MNP’s dimensions and shape and the dielectric properties of the environment [27,28,29,30,31].

Size-dependent spectral properties of noble MNPs (e.g., [32,33,34,35]) and plasmon dynamics are of basic importance in many studied plasmonic issues. The example can be harnessing hot electrons and holes, resulting from the decay of LSPs which recently attracted considerable attention because of their promising applications in photodetection, energy harvesting, hot-carrier-induced chemistry, photocatalysis, etc. [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. The performance of plasmonic devices correlate with numerous parameters that need to be studied to reach the optimum and desired properties. In all of them, LSP dynamics tailored by MNP size play a crucial role.

The shapes and the spectral widths of the MNP spectra are usually studied on the ground of the formalism known as the Lorentz-Mie scattering theory with the solutions in the form of a sum of an infinite series of the spherical multipole partial waves. Such fully classical electrodynamic description of scattering of a plane wave by a sphere (e.g., [44,45,46,47,48]) has been extended for the case of non-absorbing hosts [11], multi-layered spheres [49, 50], and arbitrary incident light beams [51]. LSP damping rates manifested in the broadening of the NPs spectra were experimentally studied in the case of the dominant dipole contribution to the spectra for NPs with available, limited sizes [33, 34, 52,53,54,55] (and references therein). The resulting damping times and the frequencies corresponding to the maxima in the far-field intensity signals are often suggested to directly characterize the LSP damping process and LSP resonance position.

However, the desired parameters (both for fundamental reasons and with a view to applications) such as size-dependent oscillation frequencies of multipolar modes corresponding to LSP’s resonances, or the decay rates (times) of the excited oscillations, are not the explicit parameters of the Lorentz-Mie scattering theory. In [56,57,58,59], such functions were derived from considering the classical dispersion relation [60, 61] for the surface localized EM (SLEM) fields basing on the self-consistent Maxwell divergent-free equations. The modelling [56,57,58,59] provides the explicit size dependence of the oscillation frequencies of SLEM fields and of the damping rates of such oscillations for the dipole and higher order multipolar surface modes and goes beyond the limitations related to the MNP’s size including those which result from the often used quasistatic approximation (e.g., [35]) which kills the size dependence (see also [17] in the case of cavity QED formalism using the electrostatic electric field potential).

However, such classical description of the dynamics of LSP damping imposes constraints to fully understand the LSP dynamics including the damping processes, because it does not distinguish between the dephasing and population damping. In case of the dipole LSP such quantities were suggested to be connected to each other [34, 53,54,55] and composed of radiative and nonradiative decay into electron-hole excitations. However, more detailed analysis of the problem was not given.

The present paper aims to present such an analysis by adopting the theory of quantum open systems and formulating the conclusions which apply to the issue of the LSP damping.

Plasmonic phenomena are inherently quantum (see, e.g., [62,63,64]). Quantum plasmonics has recently emerged as a new fascinating field of research with a view of observing quantum phenomena in light-matter interactions at the nanoscale (see [22, 63, 65,66,67] for reviews). In particular, there have been a large number of theoretical studies of interactions between a (dipole) emitters and confined plasmonic structures in weak or also in strong-coupling regime using different approaches (“macroscopic” QED using Green’s functions, quasinormal decomposition, resonant-state-expansion) [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26, 68, 69]. The confinement of light field to scales far below that met in the case of the conventional optics by metalic nanostructures enables to describe the interactions between atomic systems and plasmonic structures in the formalism of cavity QED and (see, e.g., [17]) to explore the potential of such systems [70] for developing future quantum technologies like single-photon transistor or for carrying quantum information (see [66, 67, 71] for reviews).

In this paper, we describe the intrinsic dynamics of LSP which includes the relaxation pathways leading to the dephasing and population damping of plasmon oscillations within a quantum dynamical description of open systems. The master equation in the Lindblad form within the Born-Markov approximations [72] is used to describe the evolution of an open quantum system of N electrons confined in an MNP in absence of the driving EM field. Conclusions allow to generalize the common understanding of the LSP damping as the process which consists not only from the dephasing of LSP oscillations, but also from the population damping at the twice larger rate, irrespective the MNP size and LSP multipolarity.

The results of such modeling have been related to the previously derived multipolar damping rates versus MNP radius which describe the LSP decoherence process. Such rates resulted from the dispersion relation for the surface localized electromagnetic (SLEM) fields [56,57,58,59] which we shortly reconsider for completeness of the modelling. Derived in absence of the illuminating light, the dephasing and population damping rates tailor the transient LSP dynamics but manifest also in the amplitudes and widths of the spectra. The size dependence of studied parameters allows predicting the optimum and desired properties of LSPs, being a useful tool in tailoring MNP plasmonic performance in experiments and applications also in the size regions still practically unavailable.

Plasmon Oscillatory Eigenstates (Classical Description)

Energy levels of atoms and molecules manifest in transitions from one energy level to another when they absorb and emit light. We use a similar picture of energy levels for a plasmonic system of N free-electrons confined in a spherical MNP. The starting point is based on the results of rigorous classical electrodynamic description based on the self-consistent divergent-free Maxwell equations (with no external sources). This problem was completely solved in a classical paper by Mie (1908) [44]. However, in the present study based on the formulations [21, 56,57,58,59, 61, 73,74,75], unlike in the case of the popular Lorentz-Mie scattering theory (e.g., [44,45,46,47,48]), the radiation illuminating the MNP is absent. A spherical metal/dielectric interface forms a cavity [21] which allows excitation of diverse modes of the SLEM fields in the form of the standing waves adjusted to the MNP’s dimensions. Such modes can be excited after MNP is illuminated by the light within the appropriate frequency range. The continuity relation at the spherical interface leads to a set of separate dispersion relations for each multipole mode of the partial wave. The solutions exist for TM polarized modes only, because contrary to TE modes, TM (or p polarized electric waves) posses the non-zero normal to the surface (radial) components of the electric field, which are able to couple with the surface free charges.

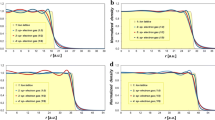

The dispersion relations for SLEM fields define the complex, discrete eigenvalues \(\hbar ({\omega }_{l}-i{\Gamma }_{l}/2)\) and connect the allowed oscillation frequency ωl and the corresponding damping rate Γl of the l th mode oscillations to the (inverse of) NS’s radius R. The size dependence of ωl(R) and Γl/2(R) define the dynamics of SLEM fields: exp(iωl −Γl/2)t) and is unambiguously determined by the material properties of the MNP and its dielectric environment. Found in absence of the illuminating radiation, ωl and Γl inherently characterize an MNP of the radius R in the same way as the energy levels and the inverse of lifetimes characterize an atom or a molecule. In both cases, these quantities manifest in the spectra, when the systems are illuminated. The example of ωl(R) and Γl(R) dependence for gold MNPs embedded in water [59] is shown in Fig. 1.

The scheme leading to the dispersion relation for SLEM fields (left) and the example of the resulting discrete complex eigenvalues \(\hbar \omega _{l}-i\hbar {\Gamma }_{l}/2\) for the consecutive modes l = 1,2,3… (right) for Au MNPs embedded in water [59]

Let us note that the problem of eigenmodes for plasmonic resonators recently attracted new interest resulting in a number of theoretical studies of quasinormal modes for plasmonic resonators and open cavities. In particular, based on the concept of the resonant-state expansion (e.g., [21, 26, 76,77,78]), it was confirmed, that an open optical system like a plasmonic confined structure can be characterized by the complex eigenfrequencies with the real and imaginary parts corresponding to, respectively, the spectral positions of the resonances and defining the spectral linewidths of resonances. However, such a classical description does not include populations of the plasmon modes nor their damping.

The next step is to replace the oscillation energies \(\hbar \omega _{l}\) (or \({\hbar \omega _{l}^{r}}\)) of the classical modes by the discrete energy levels, which are distinct from the zero-energy non-oscillatory level by the energies \(\hbar {\omega }_{l}(R)\) (or \(\hbar {\omega }_{l}^{r}(R)\)) (see Fig. 2a, b). The corresponding states of the plasmonic systems S in the Hilbert space are |ψl〉 with l = 1,2,3... (see Fig. 2b). The only possible transitions are those with the absorption or emission of a photon with the energy \(\hbar {\omega }_{l}\). Such transitions occur between the state |ψl〉 and the non-oscillatory state |ψ0〉.

The Density Matrix for N Electrons of the Plasmonic System and the Quantum Master Equation

The density matrix (the density operator) is an alternate representation of the state of a quantum system which is very convenient for systems in the mixed states and in time-dependent problems. One of the reasons to consider the mixed states is the entanglement of the systems with the environment. The diagonal elements of the density matrix correspond to the probabilities pn = Nn/N of occupying a quantum states |ψn〉, n = 0,1,2... , so they describe the relative populations of these states. The complex off-diagonal elements of the density matrix in the basis {|ψl〉,|ψ0〉} contain a time-dependent phase factors that describe the evolution of coherent superposition of the states.

The plasmonic system S we consider consists of N electrons which in general can be distributed over the states |ψn〉 , n = 0, l = 1,2... with |ψ0〉 for the ground, non-oscillatory states and |ψl〉 for the excited oscillatory states of the plasmon modes l (see Fig. 2). Coherences between the states |ψ0〉 and |ψl〉 can be created after the interaction of the system, e.g., with the external EM field. As no physical system is absolutely isolated from its surroundings, the plasmonic system S has to be considered as an open quantum system which is a subsystem of a larger combined quantum system S + E, where E represents the environment to which the open system S is coupled. Following the main assumption of the basic theory of open quantum systems [72], the environment is assumed to be a large system with an infinite number of degrees of freedom, (with a continuous and wide spectrum of characteristic frequencies) in thermal equilibrium. Therefore, the state of the system E is practically unaffected by coupling to the system S. The interaction of the open system S with the environment causes an irreversible behavior of the open system S and leads to decoherence (randomization of phases) and dissipation of energy into the surroundings.

The evolution of the open quantum system S can be described by using a master equation which defines the dynamics of the reduced density operator ρS(t) = trEρ(t) obtained after tracing out the environment degrees of freedom (e.g., [72]). The quantum Markovian process represents the simplest case of the dynamics of an open systems. Within the Markov approximation, the memory effects of the system under influence of the environment are negligible. The correlation functions of the environment decay sufficiently fast over the time τE which is small compared with the characteristic timescale of the relaxation processes τS of the system S (e.g., [72, 79,80,81]).

The dynamics of open systems in the case of Markov processes can be described by a first-order linear differential equation for the reduced density matrix, which is known as a quantum Markovian master equation in Lindblad form [81,82,83]:

where ρS(t) is the reduced density matrix of the system S, and D[ρS(t)] is the so-called dissipator:

Summation over k extends over all processes of coupling with the environment. The first term on the right-hand side of the Eq. (1) describes the unitary evolution of the system S under the action of a Hamiltonian H. The dissipator D[ρS] describes the environmental influence on the system state (e.g., [72]). The “jump” operators Lk (Eq. (2)) describe a random evolution of the system which suddenly (at the time scale of the evolution) changes under the influence of the environment. Each \(L_{k}\rho ^{S}L_{k}^{\dagger }\) term induces one of the possible quantum jumps, while the remaining terms are needed to normalize properly the case in which no jump occurs.

The simplest quantum system is a two-level system whose Hilbert space is spanned by two states, an excited state and a ground state. Such a two-level system is a very important basic model for an atom or a system of spins which is often used in quantum mechanics. The two-level system can be successfully used, provided that the transitions to other levels can be neglected.

In the case of LSPs, such picture can be related to the classical description based on Maxwell equations (see the section “??”), where the problem is solved separately for each EM mode l of the SLEM field, and the final result is a sum over the solutions for consecutive modes with l = 1,2,3.... Basing on such analogy, we describe the plasmonic system S as a sum of Sl of independent, open subsystems:

Each subsystem Sl is a two-level system: the excited states |ψl〉 and the ground non-oscillatory state |ψ0〉. The state of each subsystem Sl can be described by the 2 × 2 matrix operator \(\rho ^{S_{l}}(t)\). Each system Sl is coupled to the environment independently and all assumptions about the coupling of the system Sl to the environment remain fulfilled for subsystems S. The dynamics of the system S thus results from the independent dynamics of the systems Sl:

governed by the Lindblad Eq. (1). The form of the equation (2) guarantees that also dynamics of each matrix operator \(\rho ^{S_{l}}(t)\) is governed by the equation in the Lindblad form. Therefore, we can use the standard basis {|ψl〉,|ψ0〉} represented by the two-dimensional column vectors:

and represent the operator \(\rho ^{S_{l}}(t)\) in matrix form:

The diagonal elements of the matrix \(\rho ^{S_{l}}\) represent the relative populations (more precisely, the population probability densities) of the relevant states. The off-diagonal elements represent quantum-mechanical coherences and are complex conjugates of each other, carrying the same information.

The Hamilton operator Hl ≡ El|ψl〉〈ψl|− E0|ψ0〉〈ψ0|) with the energy eigenvalue E0 = 0 (Fig. 2) in the ground state (Hl|ψ0〉 = E0|ψ0〉 = 0):

in the chosen basis is represented by the matrix:

The commutator \(\left [ H_{l},\rho ^{S_{l}}\right ] \) possess the non-zero off-diagonal elements only.

The transition operator from the state |ψl〉 to the state |ψ0〉: σ−|ψl〉 = |ψ0〉〈ψl|ψl〉 = |ψ0〉, and its complex conjugate (σ−)‡ = σ+ (σ+|ψ0〉 = |ψl〉〈ψ0|ψ0〉 = |ψl〉) can be expressed in the basis {|ψl〉,|ψ0〉} with the use of the Pauli 2 × 2 matrices σ1 and σ2:

which are eigenoperators of the Hamiltonian Hl (Eq. (8)), which describe the emission and absorption processes. As usual, σ− is the operator lowering the energy and σ+ is the energy rising operator: \(\left [ H_{l},\sigma _{\mp }\right ] =\mp \hbar \omega _{l}\sigma _{\mp }\).

Dynamics of the Radiative Plasmon Damping

An excited plasmon, similarly as an excited atom, decays to the state of lower energy spontaneously emitting a photon. In the theory of open quantum systems, such decay is assumed to be due to the coupling of the system to the EM vacuum (fluctuating) fields. The random vacuum fluctuations (which pervades all space even at zero temperature) cause random jumps influencing plasmon evolution. In the case when only radiative damping is present, the Hamiltonian in the Linblad Eq. (1) \({H_{l}^{r}}=H_{l}\) (8) and the eigenenergy \(E_{l}=\hbar {\omega _{l}^{r}}\).

A single jump operator

describes random, sudden emission of a photon from the state |ψl〉 to the state |ψ0〉 of the Sl, with \({{\Gamma }_{l}^{r}}\) being the (spontaneous) radiation rates. The Lindblad master Eq. (1) takes then the form:

The evolution of the diagonal and off-diagonal elements of \(\rho ^{S_{l}}\)

leads to the solutions (t0 = 0):

Therefore, the radiative damping rate \({\Gamma }_{l}^{r\thinspace pop}={{\Gamma }_{l}^{r}}\) of populations ρll is twice as large as the radiative rate \({\Gamma }_{l}^{r\thinspace coh}={{\Gamma }_{l}^{r}}/2\) of coherences \(\rho _{l0}=\rho _{0l}^{*}\), so the relation between the corresponding radiative lifetimes of populations and coherences is \(2T_{l}^{r\thinspace pop}=\)\(T_{l}^{r\thinspace coh}\).

Dynamics of the Total (Radiative and Collisional) Plasmon Damping

Electrons in a metal inevitably undergo collisions which lead to the dissipation of energy and release of heat. To account for nonradiative relaxation processes, the system S interacting with fluctuations of the vacuum is assumed to be immersed in a dissipative heat-bath in a thermal equilibrium state with an infinite number of degrees of freedom. The heat reservoir dynamics is assumed to be much faster than those of the open system Sl, so the dynamics of Sl (and those of S) is Markovian. The jump operators which describe the collisional transition from the state |ψl〉 to the state |ψ0〉 are:

where \({\Gamma }_{l}^{nr}\) are the nonradiative rates describing the collisional processes leading to the heat release. Summing over radiative and nonradiative contributions in the dissipator D[ρS] (Eq. (2)), we get the master equation:

The random jumps in the evolution of \(\rho ^{S_{l}}(t)\) with the rates \({{\Gamma }_{l}^{r}}\) and \({\Gamma }_{l}^{nr}\) are assumed to be uncorrelated. The relaxation of the diagonal and off-diagonal elements of \(\rho ^{S_{l}}\) is governed by the total relaxation rate \({\Gamma }_{l}={{\Gamma }_{l}^{r}}+{\Gamma }_{l}^{nr}\). The Hamiltonian Hl (Eq. (8)) defines the eigenenergies \(E_{l}=\hbar \omega _{l}\) of the excited states |ψl〉 in presence of the radiative and nonradiative damping processes.

Using the formalism recalled in the previous section and Eq. (4), the evolution of the whole system S is described by the dynamics of the density matrix ρS(t) (Eqs. (4) and (6)):

with the diagonal and off-diagonal temporal dependence given by:

The populations of the oscillatory states are exponentially damped with the rates:

while the oscillations of coherences are damped with two times lower rate:

So the lifetime of coherences is twice as large as the lifetime of populations.

The temporal evolution of coherences \(\rho ^{S_{l}}\) proceeds according to exp(iωl −Γl/2)t, similarly to the evolution of SLEM fields, which resulted from the dispersion relation (section “??”). So, the size dependence of ωl and Γl in Eq. (20) can be found by solving the dispersion relation for SLEM field for successive R + ΔR, as it was done in our previous papers [56,57,58,59].

The density matrix ρS(t) (Eq. (20)) fulfills all the properties which are of basic importance for quantum statistics: it is positive, self-adjoint, and with the trace equal 1. The relative populations of the states |ψn〉, n = 0, l:

are the same at any time t as the initial populations

over the excited, oscillatory states |ψl〉, l = 1,2,3... at t = t0 (see Eq. (20)):

Pure Dephasing

Pure dephasing takes place where the external reservoir is the source of fluctuations which do not change the average energy of the system. These fluctuations lead to a loss of coherence in the system resulting in the decay of the off-diagonal elements of the density matrix, without affecting the diagonal elements. So, if there are processes which lead to decoherence without affecting populations, the total damping rate is increased by the “pure” decoherence rate \({\Gamma }_{l}^{\ast coh}\):

The population damping rates \({\Gamma }_{l}^{pop}\) remain unchanged:

In the case when the nanoparticle is illuminated by light, such “pure” dephasing processes introduce additional broadening to the observed spectra in which LSP excitations manifest.

Discussion and Conclusions

Localized surface plasmons in plasmonics are commonly described as the electromagnetic excitations coupled to coherent electron charge densities oscillations on a metal/dielectric interface. LSP’s parameters such as damping rates of plasmon oscillations in function of MNP’s size (related to the decoherence processes) are usually derived from the widths of scattering or absorption spectra for the dipole (l = 1) plasmon mode only. In common practice, such damping rates (and the frequencies corresponding to the maxima in the far-field intensity signals) are suggested to describe LSP dynamics what may lead to narrow understanding of LSP damping, which in fact is the process embracing dephasing and depopulation of all the plasmon modes involved, including those not evidenced as distinct maxima in the spectra. Moreover, it is known that in general LSP resonances can manifest in different manners in diverse spectra in the near- and far-field regions [84,85,86,87,88].

Solutions of the dispersion relation for SLEM fields (see the example in Fig. 1) allow to find the intrinsic LSP dephasing rates and resonance frequencies of multipolar plasmons in absence of illumination and predict their size dependence in the large range of MNP radii [56,57,58,59].

In the applied quantum description, an MNP is treated as “quasi-particle,” similarly to an atom or molecule. Such picture enables studying the intrinsic decay dynamics of both populations and coherences of the quasi-particles oscillatory states involving physical quantities and their relations which have not been discussed in the previous approaches. In particular, the damping rates of populations and of coherences of consecutive plasmon modes occur to be intrinsically different: \({\Gamma }_{l}^{pop}=2{\Gamma }_{l}^{coh}\), regardless of the MNP size.

The present paper builds the bridge between the results of the classical electrodynamic description supplying size dependence of the dephasing rates and the quantum description of the intrinsic dynamics of plasmon decay processes in MNPs which are essentially not restricted in size (see Fig. 3). Such dynamics is affected by several factors to consider such as electron dumping in bulk metal γbulk, the electron-surface scattering γR (the parameters of the dielectric function), radiation damping, and prospectively the interface damping resulting in energetic charge carriers production. In the case of solving the dispersion relation for SLEM fields using the Drude-like dielectric function (electron dumping in bulk metal with the rate γbulk and the radius-dependent electron-surface scattering rate γR accounted), the damping rates Γl(R) define the size dependence of the total population and coherence damping rates resulting from the quantum modelling: \({\Gamma }_{l}(R)={\Gamma }_{l}^{coh}(R)={\Gamma }_{l}^{pop}(R)/2\) (see Fig. 3). Such link can be a useful tool in tailoring MNP plasmonic performance in experiments and applications also in the size regions still practically unavailable. Suggested (Fig. 3) decomposition of the contribution of the radiative rates from the total damping rates after appropriate modification of the input dielectric function of gold and silver (γbulk = 0) will be the subject of our next study.

The quantum picture offers the attractive prospects for designing the plasmonic devices that operate at the quantum level and exploit their lossy nature (e.g., [36, 89,90,91]), in addition to the broad range of applications based on the enhancement of EM fields at metal/dielectric interfaces. In such a practical context, accounting for various dissipative decay channels and quantification of their importance in the plasmonic systems built of diverse material, size, and shape, embedded in various matrices, is of basic importance.

References

Barnes WL, Dereux A, Ebbesen TW (2003) Surface plasmon subwavelength optics. Nature 424 (6950):824–830

Xiong Y, Liu Z, Sun C, Zhang X (2007) Two-dimensional imaging by far-field superlens at visible wavelengths. Nano Lett 7(11):3360–3365

Wang Y, Plummer EW, Kempa K (2011) Foundations of plasmonics. Adv Phys 60(5):799–898

Zhao M, Xu W, Ren S, Xing Y, Wang J, Teng N, Zhao D, Liu W, Zhu D, Su S, et al. (2017) Cavity-type dna origami-based plasmonic nanostructures for raman enhancement. ACS Appl Mater Inter 9 (26):21942–21948

Rong G, Wang H, Skewis LR, Bjorn MR (2008) Resolving sub-diffraction limit encounters in nanoparticle tracking using live cell plasmon coupling microscopy. Nano Lett 8(10):3386–3393

Xu H, Li Q, Wang L, He Y, Shi J, Tang B, Fan C (2014) Nanoscale optical probes for cellular imaging. Chem Soc Rev 43(8):2650–2661

Lee M, Kim JU, Lee JK, Ahn SH, Shin Y-B, Shin J, Park CB (2015) Aluminum nanoarrays for plasmon-enhanced light harvesting. ACS Nano 9(6):6206–6213

Atwater HA, Polman A (2010) Plasmonics for improved photovoltaic devices. Nat Mat 9(3):205–213

Couture M, Zhao SS, Masson J-F (2013) Modern surface plasmon resonance for bioanalytics and biophysics. Phys Chem C Phys 15(27):11190–11216

Li J, Cushing SK, Meng F, Senty TR, Bristow AD, Wu N (2015) Plasmon-induced resonance energy transfer for solar energy conversion. Nat Photonics 9(9):601–607

Kolwas K, Derkachova A (2017) Modification of solar energy harvesting in photovoltaic materials by plasmonic nanospheres: new absorption bands in perovskite composite film. J Phys Chem C 121(8):4524–4539

McPhillips J, Murphy A, Jonsson MP, Hendren WR, Atkinson R, Höök F, Zayats AV, Pollard RJ (2010) High-performance biosensing using arrays of plasmonic nanotubes. ACS Nano 4(4):2210–2216

Dykman LA, Khlebtsov NG (2016) Biomedical applications of multifunctional gold-based nanocomposites. Biochem (Moscow) 81(13):1771–1789

Kolwas K, Derkachova A, Jakubczyk D (2016) Tailoring plasmon resonances in metal nanospheres for optical diagnostics of molecules and cells, Apple Acagemic Press. chapter 5

Scholl JA, Ai LK, Dionne JA (2012) Quantum plasmon resonances of individual metallic nanoparticles. Nature 483(7390): 421–427

Schirmer SG (2004) Constraints on relaxation rates for n-level quantum systems. Phys Rev A 70(2):022107

Waks E, Sridharan D (2010) Cavity qed treatment of interactions between a metal nanoparticle and a dipole emitter. Phys Rev A 82(4):043845

Vlack CV, Kristensen PT, Hughes S (2012) Spontaneous emission spectra and quantum light-matter interactions from a strongly coupled quantum dot metal-nanoparticle system. Phys Rev B 85(7):075303

Martín-Cano D, Haakh HR, Murr K, Agio M (2014) Large suppression of quantum fluctuations of light from a single emitter by an optical nanostructure. Phys Rev Lett 113(26):263605

Delga A, Feist J, Bravo-Abad J, Garcia-Vidal FJ (2014) Quantum emitters near a metal nanoparticle: strong coupling and quenching. Phys Rev Lett 112(25):253601

Doost MB, Langbein W, Muljarov EA (2014) Resonant-state expansion applied to three-dimensional open optical systems. Phys Rev A 90(1):013834

Törmä P, Barnes WL (2014) Strong coupling between surface plasmon polaritons and emitters: a review. Rep Prog Phys 78(1):013901

Esteban R, Aizpurua J, Bryant GW (2014) Strong coupling of single emitters interacting with phononic infrared antennae. New J Phys 16(1):013052

Sáez-Blázquez R, Feist J, Fernández-Domínguez AI, García-Vidal FJ (2017) Enhancing photon correlations through plasmonic strong coupling. Optica 4(11):1363–1367

Hughes S, Richter M, Knorr A (2018) Quantized pseudomodes for plasmonic cavity qed. Optics Lett 43(8):1834–1837

Lobanov SV, Langbein W, Muljarov EA (2018) Resonant-state expansion of three-dimensional open optical systems: light scattering. Phys Rev A 98:033820

Bingham JM, Anker JN, Kreno LE, Van Duyne RP (2010) Gas sensing with high-resolution localized surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy. J Am Soc 132(49):17358–17359

Anker JN, Paige Hall W, Lyandres O, Shah NC, Zhao J, Van Duyne RP (2010) Biosensing with plasmonic nanosensors. In: Nanoscience and technology: a collection of reviews from nature journals. World Scientific, pp 308–319

Stiles PL, Dieringer JA, Shah NC, Van Duyne RP (2008) Surface-enhanced raman spectroscopy. Annu Rev Chem 1:601–626

Larsson EM, Langhammer C, Zorić I, Kasemo B (2009) Nanoplasmonic probes of catalytic reactions. Science 326(5956): 1091–1094

Novo C, Funston AM, Mulvaney P (2008) Direct observation of chemical reactions on single gold nanocrystals using surface plasmon spectroscopy. Nat Nanotechnology 3(10):598–602

Mulvaney P (1996) Surface plasmon spectroscopy of nanosized metal particles. Langmuir 12(3):788–800

Kreibig U, Vollmer M (1995) Optical properties of metal clusters. Springer, Berlin

Hartland GV (2011) Optical studies of dynamics in noble metal nanostructures. Chem Rev 111(6):3858–3887

Kelly KL, Coronado E, Zhao LL, Schatz GC (2003) The optical properties of metal nanoparticles: the influence of size, shape, and dielectric environment. J Phys Chem B 107(3):668–677

Clavero C (2014) Plasmon-induced hot-electron generation at nanoparticle/metal-oxide interfaces for photovoltaic and photocatalytic devices. Nat Photonics 8(2):95

Brongersma ML, Halas NJ, Nordlander P (2015) Plasmon-induced hot carrier science and technology. Nat Nanotechnology 10(1):25–34

Knight MW, Sobhani H, Nordlander P, Halas NJ (2011) Photodetection with active optical antennas. Science 332(6030):702–704

Brown AM, Sundararaman R, Narang P, Goddard III WA, Atwater HA (2015) Nonradiative plasmon decay and hot carrier dynamics: effects of phonons, surfaces, and geometry. ACS Nano 10(1):957–966

Gong T, Munday JN (2015) Materials for hot carrier plasmonics. Opt Mater Express 5(11):2501–2512

Dal Forno S, Ranno L, Lischner J (2018) Material, size, and environment dependence of plasmon-induced hot carriers in metallic nanoparticles. J Phys Chem C 122(15):8517–8527

Deeb C, Pelouard J-L (2017) Plasmon lasers: coherent nanoscopic light sources. Phys Chem Chem Phys 19(44):29731–29741

Rajput NS, Shao-Horn Y, Li X-H, Kim S-G, Jouiad M (2017) Investigation of plasmon resonance in metal/dielectric nanocavities for high-efficiency photocatalytic device. Phys Chem Chem Phys 19(26):16989–16999

Medien G (1908) Beiträge zur optik trüber medien, speziell kolloidaler metallösungen. Ann Phys 25 (3):377–445

Bohren C, Huffman D (1983) Absorption and scattering of light by small particles. Wiley Science paperback series. Wiley, New York

Born M, Wolf E (1999) Principles of optics: electromagnetic theory of propagation, interference and diffraction of light. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Quinten M (2010) Optical properties of nanoparticle systems: Mie and beyond. Wiley, New York

Hergert W, Wriedt T (2012) The Mie theory: basics and applications, vol 169. Springer, Berlin

Bhandari R (1985) Scattering coefficients for a multilayered sphere: analytic expressions and algorithms. Appl Opt 24(13):1960–1967

Sinzig J, Quinten M (1994) Scattering and absorption by spherical multilayer particles. Appl Phys A 58 (2):157–162

Gouesbet G, Gréhan G (2011) Generalized Lorenz-Mie theories. Springer Science & Business Media, Berlin

Link S, El-Sayed MA (1999) Spectral properties and relaxation dynamics of surface plasmon electronic oscillations in gold and silver nanodots and nanorods. J Phys Chem B 103(40):8410–8426

Heilweil EJ, Hochstrasser RM (1985) Nonlinear spectroscopy and picosecond transient grating study of colloidal gold. J Chem Phys 82(11):4762–4770

Sönnichsen C, Franzl T, Wilk T, Von Plessen G, Feldmann J (2002) Plasmon resonances in large noble-metal clusters. New J Phys 4(1):93–100

Sonnichsen C, Franzl T, Wilk T, Von Plessen G, Feldmann J, Wilson Ov, Mulvaney P (2002) Drastic reduction of plasmon damping in gold nanorods. Phys Rev Lett 88(7):077402–077402

Kolwas K, Derkachova A, Shopa M (2009) Size characteristics of surface plasmons and their manifestation in scattering properties of metal particles. JQSRT 110(14):1490–1501

Kolwas K, Derkachova A (2010) Plasmonic abilities of gold and silver spherical nanoantennas in terms of size dependent multipolar resonance frequencies and plasmon damping rates. Opto-Electron Rev 18(4):429–437

Kolwas K, Derkachova A (2013) Damping rates of surface plasmons for particles of size from nano- to micrometers; reduction of the nonradiative decay. JQSRT 114:45–55

Derkachova A, Kolwas K, Demchenko I (2015) Dielectric function for gold in plasmonics applications: size dependence of plasmon resonance frequencies and damping rates for nanospheres. Plasmonics, pp 1–11

Ruppin R (1982) Electromagnetic surface modes, vol 9. Wiley, Chichester

Fuchs R, Halevi P (1992) Spatial dispersion in solids and plasmas. North-Holland, Amsterdam

Jacob Z, Shalaev VM (2011) Plasmonics goes quantum. Science 334(6055):463–464

Tame MS, McEnery KR, Özdemir ŞK, Lee J, Maier SA, Kim MS (2013) Quantum plasmonics. Nature Phys 9(6):329

Bozhevolnyi SI, Mortensen NA (2017) Plasmonics for emerging quantum technologies. Nanophotonics 6 (5):1185–1188

De Leon NP, Lukin MD, Park H (2012) Quantum plasmonic circuits. IEEE JSTQE 18(6):1781–1791

Ginzburg P (2016) Cavity quantum electrodynamics in application to plasmonics and metamaterials. Rev Phys 1:120–139

Marquier F, Sauvan C, Greffet J-J (2017) Revisiting quantum optics with surface plasmons and plasmonic resonators. ACS Photonics 4(9):2091–2101

Sauvan C, Hugonin J-P, Maksymov IS, Lalanne P (2013) Theory of the spontaneous optical emission of nanosize photonic and plasmon resonators. Phys Rev Lett 110(23):237401

Muljarov EA, Langbein W (2016) Resonant-state expansion of dispersive open optical systems: Creating gold from sand. Phys Rev B 93(7):075417

Monroe C (2002) Quantum information processing with atoms and photons. Nature 416(6877):238

Tame MS, Lee C, Lee J, Ballester D , Paternostro M, Zayats AV, Kim MS (2008) Single-photon excitation of surface plasmon polaritons. Phys Rev Lett 101(19):190504

Breuer HP, Petruccione F et al (2002) The theory of open quantum systems. Oxford University Press on Demand, London

Boardman AD, Paranjape BV (1977) The optical surface modes of metal spheres. J Phys F Met Phys 7 (9):1935

Kolwas K, Derkachova A, Demianiuk S (2006) The smallest free-electron sphere sustaining multipolar surface plasmon oscillation. Comput Mat Sci 35(3):337–341

Derkachova A, Kolwas K (2007) Size dependence of multipolar plasmon resonance frequencies and damping rates in simple metal spherical nanoparticles. Eur Phys J Spec Top 144(1):93– 99

Zhang M, Xiang H, Zhang X, Lu G (2016) Quantum electrodynamics and plasmonic resonance of metallic nanostructures. J Phys Condensed Matt 28(15):155302

Yan W, Faggiani R, Lalanne P (2018) Rigorous modal analysis of plasmonic nanoresonators. Phys Rev B 97(20):205422

Dezfouli MK, Hughes S (2018) Regularized quasinormal modes for plasmonic resonators and open cavities. Phys Rev B 97(11):115302

Bertlmann RA, Grimus W, Hiesmayr BC (2006) Open- quantum-system formulation of particle decay. Phys Rev A 73(5): 054101

Blumm K (2012) Density matrix theory and applications, vol 64. Springer Science & Business Media, Berlin

Li L, Hall MJW, Wiseman HM (2018) Concepts of quantum non-markovianity: a hierarchy. Phys Rep 759(18):1–51

Lindblad G (1976) On the generators of quantum dynamical semigroups. Comm in Math Phys 48(2):119–130

Gorini V, Kossakowski A, Sudarshan ECG (1976) Completely positive dynamical semigroups of n-level systems. J Math Phys 17(5):821–825

Zuloaga J, Nordlander P (2011) On the energy shift between near-field and far-field peak intensities in localized plasmon systems. Nano Lett 11(3):1280–1283

Kats MA, Yu N, Genevet P, Gaburro Z, Capasso F (2011) Effect of radiation damping on the spectral response of plasmonic components. Opt Express 19(22):21748–21753

Alonso-González P, Albella P, Neubrech F, Huck C, Chen J, Golmar F, Casanova F, Hueso LE, Pucci A, Aizpurua J, Hillenbrand R (2013) Experimental verification of the spectral shift between near-and far-field peak intensities of plasmonic infrared nanoantennas. Phys Rev Lett 110(20):203902

Moreno F, Albella P, Nieto-Vesperinas M (2013) Analysis of the spectral behavior of localized plasmon resonances in the near-and far-field regimes. Langmuir 29(22):6715–6721

Cacciola A, Iatì MA, Saija R, Borghese F, Denti P, Maragò OM, Gucciardi PG (2016) Spectral shift between the near-field and far-field optoplasmonic response in gold nanospheres, nanoshells, homo-and hetero-dimers. JQSRT

Verstraete F, Wolf MM, Cirac JI (2009) Quantum computation and quantum-state engineering driven by dissipation. Nature Phys 5(9):633

Linic S, Christopher P, Ingram DB (2011) Plasmonic-metal nanostructures for efficient conversion of solar to chemical energy. Nat Mater 10(12):911

Khurgin JB (2015) How to deal with the loss in plasmonics and metamaterials. Nature Nanotech 10(1):2

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kolwas, K. Decay Dynamics of Localized Surface Plasmons: Damping of Coherences and Populations of the Oscillatory Plasmon Modes. Plasmonics 14, 1629–1637 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11468-019-00958-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11468-019-00958-1