Abstract

Do Chinese-led international institutions influence human rights discourse in China? Under the leadership of President Xi Jinping, China has spearheaded the establishment of various international institutions, attracting numerous member states. States that participate in Chinese-led international institutions tend to be swayed by China's influence and are more cautious when addressing sensitive issues concerning China. Additionally, they are more likely to adopt a favorable stance towards Chinese human rights issues compared to those that are not affiliated with these institutions. This paper examines how membership in international institutions led by China affects state responses to human rights issues in China. We leverage recommendations on Chinese human rights made in the United Nations Universal Periodic Review (UN UPR) between 2009 and 2018 in two steps. First, we utilize multinomial logistic regression models to determine which choices the reviewers prefer with respect to the UN UPR recommendations: not sending, sending praising, neutral, or shaming. Second, using ordinal logistic regression models, we investigate which types of recommendations reviewers are more likely to send to China if they decide to send them. Our findings show that reviewers with greater involvement in Chinese-led international institutions are more likely to send recommendations to China, which contradicts our first hypothesis. However, reviewers are more prone to make praising recommendations, aligning with our second hypothesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics generated diplomatic uproar, with several countries expressing concern about China’s COVID-19 management policies. Some states also highlighted human rights issues, such as the enactment of Hong Kong's national security law and the treatment of ethnic minorities in Xinjiang Uyghur and Tibet. They demanded that China take responsibility, and threatened an Olympic boycott. Consequently, some countries opted for a diplomatic boycott by sending no government officials to the games, but still allowing their athletes to compete. While the Olympics went off without major incident, China's human rights were nevertheless under scrutiny once again. It is crucial to recognize that “human rights” is often the pretext used by countries worldwide to criticize China and prevent it from attaining a more prominent role in the international community.

Authoritarian regimes jeopardize their external image when they are recognized and criticized as violators of international norms.Footnote 1 Adherence to norms can provide strategic and material benefits like foreign aid and cognitive benefits like social approval and positive self-image. Therefore, the perception of noncompliance with international norms can threaten a nation’s interests [1].

Human rights are among the most significant factors influencing a country's international reputation. Authoritarian regimes, which also must manage their reputation, can use international institutions to achieve their foreign policy goals. By cooperating with other authoritarian members of regional international institutions, the regime can prevent unpleasant regime transitions [2], and encourage communication and learning among autocrats [3,4,5,6].

Due to the lack of institutions to constrain decision-making, autocrats permit themselves to use more repressive strategies to secure power [7] or prevent an undesired future after tenure [8, 9] compared to their democratic counterparts [10]. Therefore, non-democratic states are more readily condemned as human rights abusers and must take extra measures to manage their international reputation. This begins with proving that they care about human rights in the international community.

Existing studies on human rights assume that non-state actors, such as inter-governmental organizations (IGOs) and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), induce states to avoid human rights violations and adhere to international laws or norms [11,12,13,14, 30]. While previous studies focused on the role of international institutions in promoting democracy, it is necessary to examine how non-democratic states exploit these institutions to achieve their goals, including managing reputations amid human rights criticism. Though few studies examine state-level strategies of naming and shaming on human rights, they suggest that authoritarian regimes are more likely to use international institutions in their statecraft [2, 5, 15,16,17].

This study examines the Universal Periodic Reviews (UPR) of China's human rights record at the United Nations (UN). The UPR is an international human rights institution that enables interactions between actors at the national level. States can use recommendations from the UPR to initiate debates by criticizing the human rights situation of a specific country, which can harm a country's international reputation and may impose tangible or normative costs. The UPR allows China to refute criticism of its human rights violations and even to shame other states. We argue that countries that belong to Chinese-led international institutions are more susceptible to Chinese influence. Reviewers in the UPR with membership in Chinese-led international institutions are less likely to scrutinize human rights issues sensitive to China. When these countries do engage in review, they are more likely to be positive compared with those not involved with these institutions. By examining UPR cases, this study can help establish generalizable expectations of how non-democratic states use international institutions to manage their reputation.

Literature Review

Autocratic Reputation Management and International Institutions

Authoritarian regimes seek to manage their international reputations as part of their foreign policy because reputations can lead to successful cooperation and negotiation with other states. For example, if a state has a positive reputation for upholding international norms and standards, other states may be more likely to cooperate and negotiate peacefully with it [18].

Human rights are closely related to international reputation. States with good human rights records are often seen as more legitimate and trustworthy by other countries. On the other hand, states that have a poor record on human rights often face criticism and condemnation. This can harm international reputation and lead to diplomatic isolation. Since authoritarian states are frequently condemned as human rights abusers, it is necessary for them to manage reputation in order to maintain and enhance legitimacy.

One line of inquiry argues that autocracies try to promote a positive reputation on human rights because this can lead to increased economic and diplomatic cooperation [19,20,21]. Conversely, other studies suggest that not all states that join international institutions greatly adjust their behaviors and comply with norms [22,23,24]. Instead of complying with international institutions, autocrats can choose to manage their reputations via membership without improvement in domestic human rights. Primiano and Xiang demonstrate that China strategically votes in favor of human rights resolutions at the UN General Assembly to cultivate a favorable international image despite its poor domestic human rights record [67]. Hollyer investigates autocracies in human rights institutions, finding that international institutions can serve as a virtue signal that masks disregard or noncompliance of international norms the institutions pursue [25].

Despite these competing expectations, both arguments claim that human rights perceptions matter in foreign policy and authoritarian regimes view international institutions as a means of managing reputation. Membership in these institutions allows authoritarian regimes to signal commitment to upholding the norms that members share and demonstrates their willingness to cooperate with other countries despite their low limited commitment capability due to the lack of domestic accountability [19, 26]. Additionally, international institutions often have rules and procedures that govern how decisions are made and how disputes are resolved. Authoritarian regimes can increase their predictability and reduce uncertainty in their interactions with other countries by adhering to these rules and procedures [27,28,29].

Recent work suggests that authoritarian regimes have increasingly extended their regional and international influence by leading international institutions to secure their interests [31]. For instance, Debre shows that autocracies may participate in regional organizations to protect them from external interference of non-members [2]. The likelihood of regime survival increases with the degree of autocracy among members in the organization, resulting in a collaborative shielding effect. Further, Von Soest argues that authoritarian regimes might seek international collaboration to prevent democratic transition and potentially export models of authoritarianism [6].

Beyond joining existing international institutions, some authoritarian regimes have founded and dominated new ones [5, 16]. The most notable example is China under the leadership of President Xi Jinping. China has spearheaded the establishment of various international institutions, attracting numerous member states and significantly extending its influence.

Chinese Human Rights and Reputations

As a developing country, China traditionally emphasized bilateral relations and paid little attention to multilateral international conferences. Although China participated in some international institutions established by Western countries and advocated for matters of national interests, it was careful to avoid sensitive issues to minimize conflict.

China's human rights issues are no exception. Since regaining permanent membership in the UN Security Council in 1971, the Chinese government has gradually reintegrated into the international human rights regime. Initially, China avoided or passively faced human rights issues. Yet, following the Reform and Opening Up policy in 1981, China became an official member of the UN Human Rights Commission and joined several international human rights conventions, such as the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, and the Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. By signing the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) in the 1990s, the Chinese government took a more active role in international human rights institutions. By ratifying the ICESCR in 2001, China became an official member. Although the Chinese government signed on to join the ICCPR, it has yet to ratify it [32,33,34].

China's accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 played a pivotal role in its integration into the global economy and promoted rapid economic growth. This development greatly enhanced China’s political and economic influence, securing global power status while altering its foreign policy goals. In the 2000s, the diplomatic approach changed from a cautious “韜光養晦,” meaning “hide one's capabilities and bide one's time” to a more proactive “有所作为,” meaning “have some achievements.” Furthermore, since rising to power in 2013, President Xi Jinping has spread diplomatic discourse such as “the Chinese Dream” (中国梦), “A New Model of International Relations” (新型国际关系) and “A Community with a Shared Future of Mankind” (人类命运共同体) to secure and advance China's core national interests while positioning itself as a regional and global leader.

If a country desires to establish or maintain its leadership position, image and reputation management are crucial. Although China aims to become a leader on its own terms by providing foreign aid and spreading diplomatic discourse, its human rights record has been a major obstacle. As mentioned earlier, China initially responded to Western criticism by adopting the rules and norms of international human rights regimes established by the West. Despite this, China's human rights record has not met international criteria, resulting in frequent criticism. Eventually, the Chinese government revised its human rights policies and started leveraging the international system, including actively engaging with international human rights organizations. China has achieved its objectives by expanding its influence, disseminating Chinese human rights rhetoric, and even taking the lead on human rights issues [35,36,37]. In other words, China has made efforts to address human rights issues in order to manage its international reputation.

Chinese-led International Institution Formations

According to neoliberal institutionalism, international cooperation fails when there is a high cost and information asymmetry. Scholars believe that addressing these problems may require an international regime, defined by set of principles, norms, rules, and decision-making procedures around which member countries’ expectations converge [38, 39]. Furthermore, an international institution developed from such a regime acts as a management mechanism for interdependence by increasing opportunities for dialogue among countries and making it easier to establish a negotiating forum. States can use international institutions to reduce information costs by predicting not only current intentions but also future behavior. Accordingly, sharing information can aid in the resolution of information asymmetry [40]. In turn, the established international institution may have an impact on the country, changing or converging preferences within the same international institution [41,42,43,44]. Therefore, previous international institution research has concentrated on how to achieve cooperation among countries in a particular area, specifically the expansion and deepening of cooperation among participants.

Recent literature focuses on competitions within or across institutions. States may respond to dissatisfaction with current institutions by promoting reforms within them or establishing new ones [45]. Examples of regime shifting include the formation of the Group of Twenty (G20) and International Monetary Fund (IMF) reform, while examples of competitive regime creation include the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), BRICS, New Development Bank (NDB), Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). International institutions may also take on different forms. In the Asia–Pacific region, the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) primarily led regional organizations in the 1990s, while non-ASEAN countries such as the United States, China, Japan, Australia, and South Korea have been reforming or creating new institutions in place of ASEAN countries since the 2008 global financial crisis [46].

International institutions can take a formal form, such as the SCO and AIIB, or an informal form, such as forum diplomacy. Examples of the latter include the “China-versus-region” forums such as the China-Central and Eastern European Countries Cooperation (CEEC) Forum and the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC). Regional forums led by China are based on nonbinding agreements derived from the tradition of South-South cooperation and have a flexible institutional form, making them suitable for managing regional diplomatic relations [47]. Since the target region includes developing countries such as Africa, the Arab world, Central and Eastern Europe, and Latin America, China holds a comparative advantage in promoting cooperation among developing countries [48, 49, 66].

China goes beyond participating in existing international institutions. It now makes unyielding efforts to expand its influence in the international community. For example, one study shows that China led various agendas and broadened its influence within the G20 from 2008 to 2019 [68], while another finds that its influence is growing among developing countries in Central and Eastern Europe [69]. In short, while China has achieved objectives by advocating for reform in the international institutions established by Western countries, it has also established its own to great effect [50: 156–180].

Theoretical Argument

Human rights in China are frequently discussed in the international community. The Tiananmen (天安门) Square incident in 1989 was the first event that drew international attention to human rights in China. Immediately following the incident, Western countries condemned the Chinese government for human rights violations and imposed economic sanctions to demonstrate that its behavior was unacceptable.

By the mid-1990s, human rights ceased to be a major concern following state visits by US and Chinese leaders and China's accession to the ICESCR and ICCPR. The resurgence of Western criticism regarding human rights issues in China can be attributed to China's rise to power and implementation of China threat theory (中国威胁论) to keep them in check [51]. In other words, Western countries’ emphasis on China’s human rights violations is designed to tarnish its international image and reputation.

Beyond strategic considerations of Western governments, the varied international perceptions of human rights in China stem from concrete violations perpetrated by the Chinese government. The repressive actions taken by Beijing towards certain segments of its population have elicited international condemnation from Western governments and transnational civil society and organizations. The Chinese government has levied accusations against Western entities, asserting that they are engaging in the politicization of human rights [52].

In response, the Chinese government has addressed human rights issues in two ways. The first is to directly respond to criticism in the existing international human rights regime – an approach that has evolved over time. When the UN Human Rights Council was established in 2006, the Chinese government stood in solidarity with Asian countries such as India, Pakistan, Indonesia, and Bangladesh [53]. Since then, China has been assembling forces that share its values, while also presenting its own, controversial rhetoric on human rights [37]. Furthermore, the Chinese government is imitating the strategy of its critics by publicly shaming them with sarcastic comments, shifting blame, or engaging in “whataboutism.”

China also indirectly responds by creating new international institutions. China has the resources to endure the various costs of establishing a new international institution while also being relatively dissatisfied with the existing order [54, 55]. Chinese-led international institutions pursue their explicit goals, but they can also naturally improve China's global image and expand its influence [56]. Although these institutions emphasize economic ties between China and target states, they also have an underlying goal to polish China's international image and improve attitudes toward China among external audiences [57, 58].

China is leading the way in establishing international institutions, and expanding its influence by uniting with countries that share common interests and values [66]. We examine China’s growing influence in the international human rights regime using data from the UN UPR system. Through participation in this system, countries can enhance their reputation by adhering to international human rights norms. If countries have been identified or recommended as violating human rights, the reviewee can use the UN UPR system to refute or mitigate the damage by leveraging the system’s principle of equal qualifications and rights for participants.

Individual countries in the UN UPR need valid and reliable information about other countries to increase the utility and effectiveness of the strategies they can use in the system. International institutions in other areas can be important channels for obtaining such information. Relative to nonparticipating countries, member states can reduce transaction costs and get reliable information about other countries' decision-making [28]. Further, under the same institutional constraints, participants are expected to have converging preferences compared to non-participating countries [41, 44, 59]. Thus, external international institutions can influence how countries behave in the UN UPR.

This study investigates the relationship between membership in Chinese-led international institutions and the human rights discourse used by reviewers of China in the UN UPR. Reviews of Chinese human rights include recommendations requiring China to guarantee fundamental human rights. However, the Chinese government has rejected or nearly all of these recommendations. In the traditional naming and shaming framework, China was in a passive position and restricted from improving human rights. However, the UN UPR system allows China to refute the applied pressure or even apply pressure to other countries. We anticipate that the international institutions established by China will serve as indicators of who will be supportive of Chinese interests. It is reasonable to suppose that participants in Chinese-led international institutions are more likely to avoid bringing up sensitive human rights issues for China or to side with China on human rights issues. As a result, we can derive the testable hypotheses listed below.

-

Hypothesis 1: When a country joins more (less) Chinese-led international institutions, it is less (more) likely to send UN UPR recommendations to China.

-

Hypothesis 2: When a country joins more (less) Chinese-led international institutions, it is more likely to make favorable (unfavorable) UN UPR recommendations to China.

In this study, we assume that countries want to achieve the following goals through the UN UPR process. First, countries aim to improve their reputation for adhering to international norms and reduce the tangible and intangible costs of human rights violations by participating in the UN UPR system. Second, if other countries have been identified as human rights violators, they will use the UN UPR process to either refute or mitigate the damage.

Research Design

Data and Sample

Our hypotheses seek to investigate whether a country is more likely to send recommendations to the Chinese government in the UN UPR and how the severity of the recommendation varies depending on the number of Chinese-led international institution memberships. To test these expectations, we use two dependent variables that capture the choices and severity of the UN UPR recommendations reviewers make to the Chinese government on human rights issues.

Our unit of analysis is the UN UPR recommendations that China received from other countries. The temporal coverage between 2009 and 2018 includes an examination of the entire first and second cycles and part of the third cycle.Footnote 2 The Universal Periodic Review Information (UPR Info) database has information about recommendations, such as who was reviewed (Reviewee), who reviewed it (Reviewer), the regional group, organization, response to the UPR cycle, thematic issues, and type of action. In our project, the reviewed state for the main results is China.

Variables and Models

Dependent variables

We have a total of 148 to 180 different reviewers who made recommendations on human rights issues in China between February 1, 2009, and November 1, 2018. To identify the first dependent variable, choices of UN UPR recommendations, we made a profile for the Reviewers and Reviewees per each UPR cycle. For instance, if 50 Reviewers reviewed 50 Reviewees in the first cycle, we made a profile of all possible combinations with the Reviewers, Reviewees, and years from 2009 and 2018. We then create a 50 × 50 × 10 matrix, indicating all possible recommendations a Reviewer could have sent to a Reviewee in a given cycle. We code the choice as 0 for cases in which Reviewer did not send a recommendation to a Reviewee.

When a Reviewer chooses to send a recommendation, its nature can vary greatly. We determine the severity of the recommendation by comparing the level of leniency in the recommendation's content to the types of actions required for the Reviewee. We assess the seriousness of recommendations based on their actions—which include minimal action, continuing action, considering action, general action, and specific action—and manipulate the action categories into three-scale ordinal variables [60]. We label recommendations asking for minimal and continuing action as “praising,” general action as “neutral,” and considering actions and specific actions as “shaming.” Therefore, the choices of UN UPR recommendations include the category of “not sending” and the severity of recommendations (“praising,” “neutral,” “shaming”).

To better understand the context of each recommendation level, we prepared examples of each category. The examples were drawn from the list of recommendations for each cycle of the UN UPR (2009–2018) when China was the state under review. By providing these examples, we aim to illustrate the contextual differences in recommendation severity.

The first examples are from the recommendations coded as “praising.” For instance, the recommendation that Netherlands made in the first cycle in 2009 is categorized as a level 2 action (continuing action) as it emphasized the continuity of the efforts by China. By emphasizing continuity, this implies that China is on the right track in complying with the global norm of advancing the rule of law and judicial system reform. The Netherlands' recommendation applauds China's current efforts while acknowledging that there is room for improvement.

“Continue to advance the rule of law and to deepen the reform of the judicial system.”

(February 2009, 1st Cycle, Reviewer: Netherlands)

“Intensify its engagement with the international community to exchange best practices and cooperation on law enforcement supervision and training with a view to contributing to its judicial reform processes on the basis of equality and mutual respect.”

(March 2013, 2nd Cycle, Reviewer: South Africa)

“Continue its efforts to further ensure ethnic minorities the full range of human rights including cultural rights.”

(November 2018, 3rd Cycle, Reviewer: Japan)

Secondly, we highlight examples of neutral recommendations toward China. Germany recommended that the Chinese government should "ensure every detainee has the right to regularly see visitors and has permanent access to legal counsel and effective complaint mechanisms" in the second cycle in 2013. The UN UPR info categorized this recommendation as a level 4 action that requires China to take “general action.” Although Germany described the current situation of human rights abuses for detainees in China and expected that China improves its effort to comply with global human rights norms, the recommendation still does not condemn nor praise the current policies or practices with an intent to induce substantial behavioral change. Thus, we coded this recommendation category as “neutral.”

“Accelerate legislative and judicial reforms, particularly on death penalty and administrative detention, to be in compliance with the ICCPR.”

(February 2009, 1st Cycle, Reviewer: Canada)

“Ensure every detainee has the right to regularly see visitors and has permanent access to legal counsel and effective complaint mechanisms.”

(March 2013, 2nd Cycle, Reviewer: Germany)

“Strengthen efforts, in accordance with the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, to reduce the adverse environmental effects of industrialization including air pollution."

(November 2018, 3rd Cycle, Reviewer: South Korea)

The last example is a “shaming” recommendation from South Korea, stating that China should “remove restrictions on freedom of expression and press freedom, including on the Internet, that are not in accordance with international law.” From this recommendation, there are two essential parts: demand for further compliance and substantial change of current practices. Compared to other categories, this recommendation demands specific changes toward compliance with global human rights norms. Not only does South Korea expect China to improve their behaviors but also substantially change stigmatized policies or practices. The more specific the recommendation, the greater the stigma, as they specify what policies and practices are problematic and need to be addressed.

“Grant greater access to Tibetan areas for OHCHR and other United Nations bodies, as well as diplomats and the international media.”

(February 2009, 1st Cycle, Reviewer: United Kingdom)

“End the use of harassment, detention, arrest, and extralegal measures such as enforced disappearance to control and silence human rights activists as well as their family members and friends.”

(March 2013, 2nd Cycle, Reviewer: United States)

“Remove restrictions on freedom of expression and press freedom, including on the Internet, that are not in accordance with international law.”

(November 2018, 3rd Cycle, Reviewer: South Korea)

Explanatory variables

Since this paper investigates the effect of involvement with Chinese-led international institutions on the change in attitudes toward China in human rights issues, we need to define our main explanatory variable by conceptualizing and operationalizing which institutions are Chinese-led.

Figure 1 displays the distributions of maximum values of the number of Chinese-led international institution memberships for Reviewers between the first and third cycles. We select seven Chinese-led international institutions. There are three formal institutions: AIIB, SCO, and NDB. Additionally, there are four informal institutions: FOCAC, China-Arab states Cooperation Forum (CACF), China- CEEC cooperation forum, and China-Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) cooperation forum. AIIB, SCO, and NDB have all been led by China since their establishment. The informal institutions, a new type of multilateral conference led by China, are all included in the analysis.

Both the formal and informal international institutions in this project do not prioritize human rights issues. However, human rights are mentioned in the institutions' joint declarations and communiqués. For example, the Dushanbe Declaration, issued to commemorate the SCO's 20th anniversary, uses the term “human rights” nine times, linking them to non-interference in internal affairs. The word “human rights” appears three times in the declaration of the Eighth Ministerial Conference in Dakar in 2021 in FOCAC. As a result, member states of Chinese-led international institutions often address human rights issues through mutual agreement, upholding China's perspective.

In our design, membership in formal Chinese-led institutions, such as AIIB, SCO, and NDB, ranges in value between zero and three. For instance, if a country is a member of all three institutions, its membership value is three. Similarly, membership in informal Chinese-led institutions ranges from zero to four. However, there is no country that belongs to three or four informal forums. Lastly, we combine the two categories and show the distribution of membership in all Chinese-led international institutions. The combined category ranges from zero to four, as no country exceeds four memberships between both categories.

To account for the influence of geopolitical affinity between reviewing states and China, we use a variable updated by Terman and Voeten [60]. We estimate Geopolitical Affinity as the absolute distance between ideal points among reviewing states and China based on voting records in the United Nations General Assembly. We multiply the absolute distance by minus one so that larger values represent smaller ideological distance and convergence on global issues [60]. Accordingly, we can anticipate that lower Geopolitical Affinity between the Reviewers and China is associated with a higher likelihood of sending a “shaming” recommendation.

The size of Reviewers' economy may also influence the choices and severity of recommendations. Typically, scholars use economic size as a proxy for measuring national power. When a reviewer state has enough economic capability, it is less likely to hesitate to make publicly shaming human rights recommendations to China. We include logged GDP per capita, which is measured by the World Bank's World Development Indicator Gross Domestic Product per capita constant 2015 U.S. dollars (ln(GDPpc)). The distribution is normalized and converted to a percentage point unit change using the natural logarithm.

Next, we consider the characteristics of reviewers. We create variables (HRC Member (Reviewer)) to measure whether a reviewing state sits on the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC). When a reviewer belongs to the UNHRC, we can expect that it is more likely to care about human rights issues. Reviewer's region: Asia is a variable that determines whether a Reviewer is an Asian country. One of the formal Chinese-led international institutions, AIIB, has the goal of improving infrastructure and strengthening the economies of countries in Asia. Thus, Asian countries can benefit more under the AIIB than non-Asian countries. This is a binary variable created from V-Dem project data indicating a country’s region. The original variable has six political and geographical classifications of world regions. We coded Reviewer's region: Asia as 1 if a country belongs to the Asia and Pacific excluding Australia and New Zealand category, and 0 otherwise.

We also include several human rights issues as control variables because states may have priorities on different issues. We employ an automatic clustering algorithm to aggregate issues from the first round to the third round of the UPR into manageable categories [60]. Among the issues categorized, we control for socio-economic rights and physical integrity rights because these issues may influence the severity of recommendations toward China. Because of China's rapid economic growth, it is likely to receive positive feedback on socioeconomic human rights issues, whereas physical integrity rights are more likely to receive negative feedback due to issues such as the Chinese repression of Uyghurs in Xinjiang. Finally, the model includes year dummies. The year-fixed effects allow us to account for any global time trends in UPR recommendations between reviewing states and China.

We also control for the number of recommendations that Reviewers make to Reviewees without China and the average number of international organization memberships that Reviewers had between 2003 and 2007 from the Intergovernmental Organization datasets of the Correlates of War project [61]. We suspect that a Reviewer who has been heavily involved in international relations activities will make more recommendations, even if the Reviewer is not associated with the Reviewee. Since UN UPR has a four-and-half-year period review cycle, this considers the influence of international engagement that a Reviewer can have before the first cycle of UPR begins. Finally, to account for potential influence of economic ties between Reviewer and Reviewee before UPR begins can matter, we include average bilateral trade with China from 2003 and 2007 from the Bilateral trade datasets of the Correlates of War project [62, 63]. We take the natural logarithm for these three variables and interact them with cycle variables. The list of variables and descriptive statistics for the samples in use are shown in Table A.1. in the appendix.

Model Specifications

Our dependent variables are the choices and the level of severity in UPR recommendations. The former has four categories of “Not sending,” “Praising,” “Neutral,” and “Shaming.” The latter is bounded from 1 (“Praising”) to 3 (“Shaming”) without “Not sending.” Suppose we estimate the bounded dependent variable using an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression model without additional adjustments. In this case, we risk encountering extrapolation—a functional form problem [64]. In addition, it is difficult to explain how explanatory variables affect the discrete dependent variable in OLS, as the model treats the dependent variable as continuous. This leads to challenges in interpreting the effects of predictors, given that OLS lacks information about the categories or ranks that the dependent variables include. For these reasons, we use multinomial logistic regression and ordinal logistic regression models with cycle-fixed effects as benchmark models.

Empirical Analyses

Multinomial Logistic Regression Results

The first step in our analyses focuses on the choices of UPR recommendations that Reviewers made to China. We use multinomial logistic regression models to examine the likelihood of selection in all cases where Reviewers have the option to abstain from sending recommendations. Table 1 shows the results of our Hypothesis 1 tests. Table 1 contains nine models, each relating to a different selection of UPR recommendations based on the number of memberships in Chinese-led international institutions. All models include the full set of control variables described above along with our variables of interest. In our discussion of the results below, we focus on our preferred specification for total institutions presented in Table 1.

The results are insufficient to adequately support Hypothesis 1. Surprisingly, the results contradict our initial expectations. The interpretation of results in Table 1 is complicated, particularly when comparing them to the “Not sending” reference category. To improve understanding of these findings, Fig. 2 shows predicted probabilities of opting not to send a recommendation to China, as opposed to the summed predicted probabilities of selecting other available options.

Predicted probabilities of the ‘Not sending’ UN UPR recommendations by the number of Chinese-led international institution memberships from Table 1, Model 7–9

While our Hypothesis 1 expects a positive and statistically significant relationship between the number of Chinese-led international institution memberships and the act of not sending recommendations to China from 2009 to 2018, Fig. 2 shows a significant contrast. Reviewers who participate in the UPR process are more likely than not to forward human rights recommendations to China, especially when they are affiliated with an increasing number of Chinese-led international institutions. Furthermore, as shown in Table 1, the more memberships they have in Chinese-led international institutions, the more likely they are to issue praising human rights recommendations compared to none at all.

Ordinal Logistic Regression Results

Table 2 reports the results of the ordinal logistic regression models that include only those that made recommendations. The full results with control variables can be found in the appendix. Reflecting theoretical expectations, the estimates show that as a Reviewer has more memberships in Chinese-led international institutions, it is less likely to make “shaming” recommendations to China. However, the relationship between the number of Chinese-led international institutions and the level of severity in UPR recommendation is only statistically significant when we measure the total institutions, combining formal and informal institutions.

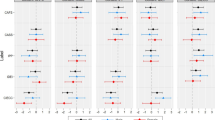

Figure 3 displays the predicted probabilities of Model 3. This provides insight into the question: how does the probability of the severity of UPR recommendation change as the total number of memberships increases? We expect that when a state participates in more Chinese-led international institutions, the state tends to have converging preferences with China and show a supportive attitude to China in the UN UPR.

The figure indicates that an increase in the number of memberships in Chinese-led international institutions decreases the probability of making shaming recommendations while increasing the probability of sending praising recommendations. However, the predicted probability of making neutral recommendations does not vary across the number institution memberships.

To check the robustness of our findings, we conduct a placebo test (Fig. 3) in which we estimate ordinal regression models for the thirty-nine authoritarian regime Reviewees as well as China. We employ Boix, Miller, and Rosato’s dichotomous measurement of political regime from the V-Dem datasets [65]. We exclude authoritarian Reviewees, which demonstrate regime transition during UPR cycles.Footnote 3 Table C.1. in appendix contains a list of authoritarian regimes for the placebo test.

The shaded area shows the results of ordinal logistic regression models for other authoritarian regimes. We can see the effect of Chinese-led international institution memberships on the level of severity of UPR recommendations are clearer when China is a Reviewee. As the number of formal and informal Chinese-led international institution memberships increases, Reviewers tend to send praising recommendations to China and are less likely to make shaming recommendations. Thus, we find sufficient empirical evidence to support Hypothesis 2.

Conclusion

By establishing Chinese-led international institutions, the Chinese government expands its influence in the international community and attempts to alter the responses of other states regarding Chinese human rights issues. Despite the fact that China has established international institutions with a variety of agendas, all Chinese-led institutions are expected to represent some aspect of Chinese interest. The number of Chinese-led international institution memberships reflect a country's exposure to China's international agenda. As a result, states participating in more Chinese-led international institutions tend to align their positions with China’s preferences on a wide range of global issues.

This paper anticipates that states that join more Chinese-led international institutions avoid bringing up sensitive issues for China and are more likely to express solidarity with Chinese human rights issues. We use multinomial and ordinal logistic regression models to empirically test our theoretical expectations with a data set of recommendations from the UN UPR Information. The findings show a significant trend. On average, states that participate in the UN UPR process do not send human rights recommendations to China. However, as states gain membership in Chinese-led international institutions, they prefer sending praising recommendations to nothing, contradicting our first hypothesis.

The severity of the UN UPR recommendations reveals important insight into the broader impact of Chinese-led international institutions, particularly when it comes to issuing recommendations to China. These findings imply that reviewers with more memberships in Chinese-led international institutions are more likely to be supportive of China's approach to human rights than their counterparts.

The results of this study point to clear avenues for future research. The findings also prompt examination of the spill-over effects of Chinese-led international institutions across various international realms. The argument advanced here has implications for the determinants of attitudes in the recommendations for human rights issues as well. Given the type of Chinese-led international institutions and the human rights recommendations towards China, states may show varying attitudes even in human rights issues to enhance proximity with China.

The UN UPR recommendations analyzed in this paper are diplomatic documents with a relatively weak tone of expression, making it challenging to detect clear changes. Future research should find credible data containing mutual remarks on human rights between China and other countries to supplement this limitation. Advanced text analysis techniques could examine how the contents of the recommendations change over time or the extent to which they are under the influence of Chinese-led international institutions. These efforts would build more valid and reliable measurements to evaluate international human rights perceptions.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Sanghoon Park, upon reasonable request.

Notes

In this paper, we use the terms referring to non-democracies, such as authoritarian regimes, dictatorships, and autocracies, interchangeably.

The third cycle runs from 2017 to 2021, but the data used in this project only includes recommendations sent to China during the UN UPR process up to November 1, 2018. Up to date information on the UN UPR can be found at upr-info (http://www.upr-info.org, searched on: August 16, 2020).

Bangladesh, Burundi, Comoros, Ecuador, Fiji, Georgia, Honduras, Liberia, Maldives, Nepal, Niger, Nigeria, Pakistan, Paraguay, Solomon Islands, Thailand, Tunisia, and Zambia are not included. Ordered alphabetically.

References

Erickson, J.L. 2020. Punishing the Violators? Arms embargoes and economic sanctions as tools of norm enforcement. Review of International Studies 46 (1): 96–120.

Debre, M.J. 2021. Clubs of autocrats: regional organizations and authoritarian survival. The Review of International Organizations 17: 1–27.

Collins, P.M. 2008. Friends of the court: interest groups and judicial decision making. New York: Oxford University Press.

Libman, A., and A.V. Obydenkova. 2013. Communism or communists? soviet legacies and corruption in transition economies. Economics Letters 119 (1): 101–103.

Libman, A., and A.V. Obydenkova. 2018. Regional international organizations as a strategy of autocracy: the eurasian economic union and russian foreign policy. International Affairs 94 (5): 1037–1058.

Von Soest, C. 2015. Democracy prevention: the international collaboration of authoritarian regimes: the international collaboration of authoritarian regimes. European Journal of Political Research 54 (4): 623–638.

Bueno de Mesquita, B., J.D. Morrow, and A. Smith. 2003. The logic of political survival. Cambridge, M.A: MIT Press.

Albertus, M., and V. Menaldo. 2014. Dealing with dictators: negotiated democratization and the fate of outgoing autocrats. International Studies Quarterly 58 (3): 550–565.

Debs, A., and H.E. Goemans. 2010. Regime type, the fate of leaders, and war. American Political Science Review 104 (3): 430–445.

Davenport, C. 2007. State repression and political order. Annual Review of Political Science 10 (1): 1–23.

Franklin, J.C. 2008. Shame on you: the impact of human rights criticism on political repression in Latin America. International Studies Quarterly 52 (1): 187–211.

Franklin, J.C. 2015. Human rights naming and shaming: International and domestic processes. In The politics of leverage in international relations: Name, shame, and sanction, ed. H.R. Friman, 43–60. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Keck, M.E., and K. Sikkink. 1998. Activists beyond borders: advocacy networks in international politics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Kim, D. 2015. Mobilizing ‘Third-Party Influence’: The impact of amnesty International’s Naming and Shaming. In The politics of leverage in international relations: Name, shame, and sanction, ed. H.R. Friman, 61–85. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bozóki, A., and D. Hegedűs. 2018. An externally constrained hybrid regime: hungary in the European union. Democratization 25 (7): 1173–1189.

Libman, A., and A.V. Obydenkova. 2018. Understanding authoritarian regionalism. Journal of Democracy 29 (4): 151–165.

Soong, J.-J. 2021. The political economy of China’s rising role in regional international organizations: are there strategies and policies of the Chinese way considered and applied? The Chinese Economy 55 (4): 243–254.

Crescenzi, M. J. C. 2018. How Reputation Matters in International Relations. In: Of Friends and Foes: Reputation and Learning in International Politics, 58–84. New York: Oxford University Press.

Avdeyeva, O.A. 2012. Does Reputation matter for states’ compliance with international treaties? States enforcement of anti-trafficking norms. The International Journal of Human Rights 16 (2): 298–320.

Garriga, A.C. 2016. Human rights regimes, reputation, and foreign direct investment. International Studies Quarterly 60 (1): 160–172.

Lenz, T., and L.A. Viola. 2017. Legitimacy and institutional change in international organisations: a cognitive approach. Review of International Studies 43 (5): 939–961.

Hafner-Burton, E.M., and K. Tsutsui. 2007. Justice lost! the failure of international human rights law to matter where needed most. Journal of Peace Research 44 (4): 407–425.

Hafner-Burton, E.M., and K. Tsutsui. 2005. Human rights in a globalizing world: the paradox of empty promises. American Journal of Sociology 110 (5): 1373–1411.

Simmons, B.A. 2009. Mobilizing for human rights: international law in domestic politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hollyer, J.R., and B.P. Rosendorff. 2011. Why do authoritarian regimes sign the convention against torture? signaling, domestic politics and non-compliance. Quarterly Journal of Political Science 6: 275–327.

Gehlbach, S., and P. Keefer. 2011. Investment without democracy: ruling-party institutionalization and credible commitment in autocracies. Journal of Comparative Economics 39 (2): 123–139.

Abbott, K.W., and D. Snidal. 1998. Why states act through formal international organizations. Journal of conflict resolution 42 (1): 3–32.

Keohane, R.O., and L.L. Martin. 1995. The promise of institutionalist theory. International Security 20 (1): 39–51.

Poast, P., and J. Urpelainen. 2013. Fit and feasible: why democratizing states form, not join, international organizations. International Studies Quarterly 57 (4): 831–841.

Risse, T., and K. Sikkink. 1999. The socialization of international human rights norms into domestic practices: Introduction. In The power of human rights: International norms and domestic change, ed. T. Risse, S.C. Ropp, and K. Sikkink, 1–38. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cheng, C. 2019. The Logic behind China’s Foreign Aid Agency. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace 21: 1–4.

Kent, A. 1999. After Vienna: China’s Implementation of Human Rights. In: China, the United Nations, and Human Rights, 194–231. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Lee, K. 2007. China and the international covenant on civil and political rights: prospects and challenges. Chinese Journal of International Law 6 (2): 445–474.

Lewis, M.K. 2021. Why China should unsign the international covenant on civil and political rights. Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law 53 (1): 131–206.

Chen, T.C., and C. Hsu. 2021. China’s human rights foreign policy in the Xi Jinping era: normative revisionism shrouded in discursive moderation. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 23 (2): 228–247.

Kinzelbach, K. 2012. An analysis of China’s statements on human rights at the United Nations (2000–2010). Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 30 (3): 299–332.

Zhang, Y., and B. Buzan. 2020. China and the global reach of human rights. The China Quarterly 241: 169–190.

Krasner, S.D. 1982. Structural causes and regime consequences: regimes as intervening variables. International Organization 36 (2): 185–205.

Ruggie, J.G. 1975. International responses to technology: concepts and trends. International Organization 29 (3): 557–583.

Keohane, R.O., and J.S. Nye. 2001. Power and Interdependence. New York: Longman.

Bearce, D.H., and S. Bondanella. 2007. intergovernmental organizations, socialization, and member-state interest convergence. International Organization 61 (4): 703–733.

Checkel, J.T. 1999. Social construction and integration. Journal of European Public Policy 6 (4): 545–560.

Finnemore, M., and K. Sikkink. 1998. International norm dynamics and political change. International Organization 52 (4): 887–917.

Johnston, A.I. 2001. treating international institutions as social environments. International Studies Quarterly 45 (4): 487–515.

Morse, J.C., and R.O. Keohane. 2014. Contested multilateralism. The Review of International Organizations 9 (4): 385–412.

He, K. 2019. Contested multilateralism 2.0 and regional order transition: causes and implications. The Pacific Review 32 (2): 210–220.

Jakóbowski, J. 2018. Chinese-led Regional multilateralism in Central and Eastern Europe, Africa and Latin America: 16 + 1, FOCAC, and CCF. Journal of Contemporary China 113: 659–673.

Alden, C., and A.C. Alves. 2017. China’s Regional forum diplomacy in the developing world: socialisation and the ‘Sinosphere.’ Journal of Contemporary China 103: 151–165.

Contessi, N.P. 2009. Experiments in soft balancing: China-led multilateralism in Africa and the Arab world. Caucasian Review of International Affairs 3 (4): 404–434.

Morton, K. 2020. China’s global governance interactions. In China and the world, ed. D. Shambaugh, 156–180. New York: Oxford University Press.

Qi, Z. 2005. Conflicts over human rights between China and the US. Human Rights Quarterly 27 (1): 105–124.

Chen, Y.-J. 2019. China’s challenge to the international human rights regime. International Law and Politics 51: 1179–1222.

Foot, R., and R.S. Inboden. 2014. China’s influence on Asian States during the creation of the U.N. human rights council: 2005–2007. Asian Survey 54 (5): 849–868.

Lim, Y.-H. 2015. How (Dis)satisfied is China?: A power transition theory perspective. Journal of Contemporary China 92: 280–297.

Zhao, S. 2018. A revisionist stakeholder: China and the post-world war II world order. Journal of Contemporary China 113: 643–658.

Ping, S.-N., Y.-T. Wang, and W.-Y. Chang. 2022. The effects of China’s development projects on political accountability. British Journal of Political Science 52 (1): 65–84.

Ambrosio, T. 2008. Catching the ‘shanghai spirit’: how the shanghai cooperation organization promotes authoritarian norms in Central Asia. Europe-Asia Studies 60 (8): 1321–1344.

Gurol, J. 2023. The authoritarian narrator: China’s power projection and its reception in the gulf. International Affairs 99 (2): 687–705.

Chelotti, N., N. Dasandi, and S. JankinMikhaylov. 2022. Do intergovernmental organizations have a socialization effect on member state preferences?: evidence from the UN general debate. International Studies Quarterly 66 (1): 1–17.

Terman, R., and E. Voeten. 2018. The relational politics of shame: evidence from the universal periodic review. The Review of International Organizations 13 (1): 1–23.

Pevehouse, J.C.W., T. Nordstron, R.W. McManus, and A.S. Jamison. 2020. Tracking organizations in the World: The correlates of War IGO version 3.0 datasets. Journal of Peace Research 57 (3): 492–503.

Barbieri, K., and O. M. G. Keshk. 2016. Correlates of war project trade data set codebook, Version 4.0. Available at https://correlatesofwar.org/data-sets/bilateral-trade. Accessed 26 Nov 2023.

Barbieri, K., O.M.G. Keshk, and B.M. Pollins. 2009. Trading data: Evaluating our assumptions and coding rules. Conflict Management and Peace Science 26 (5): 471–491.

Long, J.S. 1997. In Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables, vol. 7. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Boix, C., M. Miller, and S. Rosato. 2013. A complete data set of political regimes, 1800–2007. Comparative Political Studies 46 (12): 1523–1554.

Qian, J., J.R. Vreeland, and J. Zhao. 2023. The impact of China’s AIIB on the world bank. International Organization 77 (1): 217–237.

Primiano, C.B., and J. Xiang. 2016. Voting in the UN: A second image of China’s human rights. Journal of Chinese Political Science 21: 301–319.

Kirton, J.J., and A.X. Wang. 2023. China’s Global leadership through G20 compliance. Chinese Political Science Review 8 (3): 381–421.

Turcsanyi, R.Q., K. Liškutin, and M. Mochtak. 2023. Diffusion of influence? detecting China’s footprint in foreign policies of other countries. Chinese Political Science Review 8 (3): 461–486.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their suggestions. Acknowledgment is also made to Sung Min Han, Tobias Heinrich, and Matthew C. Wilson for their helpful comments, and to the Walker Institute at the University of South Carolina for its support.

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Carolinas Consortium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicting Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare, financial or personal.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, H., Park, S. Expanding China’s Influence via Membership: Examining the Influence of Chinese-Led International Institutions on Responses to Human Rights Issues in China. J OF CHIN POLIT SCI (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-024-09886-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-024-09886-2