Abstract

Corruption is widespread and preventive strategies to reduce corruption need to be adapted within the local context. Considering the United Nations (UN) Convention against corruption as our starting point, the paper presents a literature review based on 118 articles on corruption prevention initiatives in the public sector. The analysis indicates a substantial alignment between the guidelines deriving from the UN Convention, except for a lack of work on the risk-based approach to corruption prevention. Further, the review indicates problems with research designs. Based on the insights generated from the analysis, we develop an agenda for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Corruption is widely recognized as a social plague that affects most countries worldwide. The so-called ‘syndromes of corruption’, such as elite cartels, clans and oligarchs described by Johnston (2005), locate corruption scenarios in different contexts. Certainly, both the public sector (Anechiarico and Jacobs, 1996; Auriol & Blanc, 2009) and the private sector (Argandoña, 2003; Castro et al., 2020; Lange, 2008) suffer from corruption. A significant portion of the specialized literature, focusing on the public sector during the end of the 1990s, highlights the harmful effects of corruption. There is evidence that corruption reduces investment (Mauro, 1995) and foreign direct investment (Wei & Wu, 2001), damages productivity and economic growth as a whole (Hall & Jones, 1999), diminishes the quality of procurement services (Rose-Ackerman, 1997), exacerbates income inequality and poverty (Gupta et al., 2002) and hampers efficient and effective allocation of resources of public expenditure (Tanzi & Davoodi, 1997).

Against this background, a growing interest emerged at the beginning of the 2000s in combating corruption not only through counter policies aimed at punishing corruption but also with prevention policies aimed at limiting the occurrence of potential effects. A significant milestone that marked a significant change in the anti-corruption strategy was sparked by the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC) that was opened for signature in Merida in 2003, adopted by the UN General Assembly on 31 October 2003 (resolution 58/4), and entered into force on 14 December 2005 (in accordance with article 68(1)). According to the UN, this was “the only legally binding universal anti-corruption instrument” that affirmed the preventive approach to the corruption phenomenon. The Convention has become a milestone for the public sector in promoting and strengthening measures “to prevent the most prevalent form of corruption” (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2003, p. iii). Starting from the premise that “a comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach is necessary to effectively prevent and combat corruption”, chapter no. 2 is devoted to corruption prevention measures. It thus inextricably links the concept of prevention with policies and practices of intervention both at the national level, calling for “appropriate legislative and administrative measures”, and at the level of the individual organization calling for (among other things) maintaining and strengthening “systems for the recruitment, hiring, retention, promotion, and retirement of public employees”, as well as implementing “codes or standards of conduct”. This is particularly relevant for public procurement and public financial management, with their emphasis on implementing reporting systems, adopting accounting and auditing standards, implementing system of risk management and internal control.

With this integrated and multidisciplinary approach to corruption prevention, inspired by the work within the OECD (2000), public and private organizations might develop and implement more accurate, realistic, and effective preventive actions as these measures are linked to the assessment of the corruption causes to which organizations are potentially exposed.

Furthermore, within the framework of the general principles defined by the UNCAC, each State must adopt the mentioned basic rules in its context according to the fundamental principles of its legal, organizational, and cultural system. Certain scholars (Hopkin, 2002; Meagher, 2004) and governmental organizations (McCusker, 2006; Disch et al., 2009; OECD, 2008) emphasize design and implementation at the national level and thereby contribute to this framework of renewed interest in prevention policies.

However, little is known about governments' implementation of corruption prevention strategies inspired by these renewed international guidelines. While corruption is increasingly seen as a risk to public organizations, the prevention activities undertaken by such organizations or the results of these activities for the public institutions themselves are poorly understood (Miller et al., 2008; Power, 2007).

Considering the above, this paper presents a literature review based on 118 articles on corruption prevention initiatives in the public sector published between 2001 and 2020. Given the aforementioned need to adopt anti-corruption measures in their reference context, we defined clear selection criteria for the articles included in the review: We focus on upper-middle-income (with a GNI per capita between $4,046 and $12,535) and high-income countries (with a GNI per capita of $12,536 or more) as defined by the World Bank, that are often considered less vulnerable to corruption. As Graycar and Monaghan (2015, p. 587) assert, “corruption is different between countries with established democracies and those in a state of political-economic development or transition”. Consequently, anti-corruption measures should vary with the state of development in a given country. Hence, focusing our review on richer countries provides a purposeful grouping and can potentially deliver additional insights concerning anti-corruption measures.

Therefore, we aim to make three main contributions to the research field. First, by focusing on the anti-corruption measures, we shed light on the extent to which evidence has been generated on their use and effectiveness. Second, by giving a central role to the organizational and individual level in corruption studies, we shift attention to the practices and processes of implementation that can affect their effectiveness within public institutions. Third, arising from the integrated nature of the review, we propose an agenda for future research on corruption prevention.

The paper proceeds as follows. The following section introduces a conceptualization of corruption; the third section presents the major streams in corruption prevention research, and the fourth section outlines the agenda for future research.

The Nature and the Causes of Corruption

If, as already mentioned, the analysis and therefore the awareness of the effects of corruption have certainly motivated a renewed interest on the part of institutions in activating policies of prevention and not only of contrast, on the other hand, it is precisely the desire to "prevent" that makes in-depth study of the nature and causes of corruptive phenomena increasingly relevant. Dimant and Tosato (2018) summarise findings relating to 22 single causes of corruption (see Table 1 in Dimant & Tosato 2018 for a summary), also identifying new developments. For example, there is evidence that corruption is contagious and spills over to neighboring countries and it works both ways, i.e., for corruption prevention policies. This is a field of investigation that is characterized by a long tradition of studies, demonstrating unequivocally the complex and multidimensional nature of corruption (Capasso & Santoro, 2018) and, therefore, the multifaceted nature of the motivation to engage in corrupt behavior (Bicchieri & Ganegonda, 2017; Dimant & Schulte, 2016), which requires a multilevel analysis approach where micro-meso and macro-level are necessarily interdependent. In particular, as Aguirre (2008, p. 13) argues, "addressing one level of the triad, without ignoring another, renders the entire system ineffective."

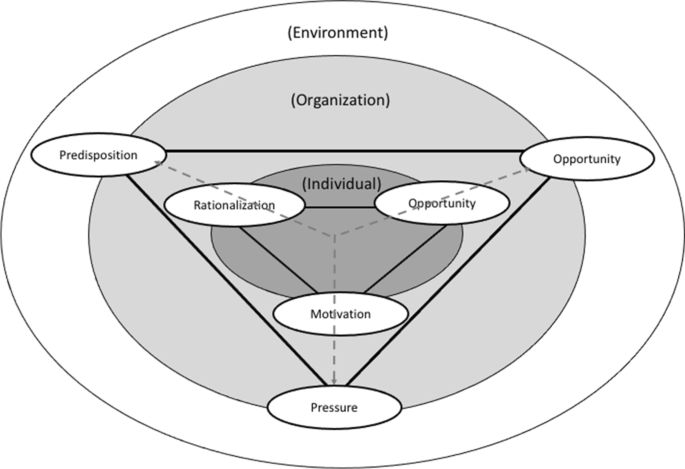

Approaches to understanding corruption at the micro-level have invoked the “bad apples” analogy (Anand et al., 2004), i.e., such approaches emphasize the combination of contextual and individual psychological factors that bring about corrupt behavior as a result of questionable moral standards. For example, according to Cressey’s (1953) fraud triangle model, opportunity, motivation, and rationalization efforts combine to enable corrupt behavior. While such individual-level explanations remain popular in applied empirical research on fraud and corruption (Homer, 2020; Le et al., 2021), researchers also criticized the fraud triangle for its heavy emphasis on individual-level factors, which are unable to explain more socio-systemic triggers of fraud (Suh et al., 2020) and its incapacity to capture different notions of financial crimes (Huber, 2017). Notwithstanding these criticisms, a detailed analysis of the origins and use of the fraud triangle by Morales et al. (2014) identifies the fraud triangle as a trigger stimulating the development of organizational controls as a countermeasure to the emergence of corrupt behavior. Consequently, Morales et al., (2014, p.185) conclude that the “(…) fraud triangle has been harnessed as a tool, in the service of practitioners and theorists, to promote a branch of knowledge that views fraud at the juncture of an individual and organizational problem”. In fact, part of the specialized literature has devoted itself to this over time (Hinna et al., 2018), studying the basis of the corruption phenomenon at the firm level, thus integrating itself into a more traditional and established macroeconomic literature, by offering a socio-psychological view on why individuals engage in corrupt acts.

Specifically, focusing on the organizational level of corruption, the literature has analyzed the causes of corruption from the point of view not only of what determines the “opportunity” of a corrupt action but also of what could “incentivize” it, combining a macro level of analysis with a meso level of analysis. In terms of opportunity, Klitgaard et al., (2000, p. 35) state that an individual “will have the opportunity to garner corrupt benefits as a function of their degree of monopoly over a service or activity, their discretion in deciding who should get how much, and the degree to which their activities are accountable”. It follows that, on the opportunity side, the prevention of corruption can be effectively achieved through an improvement of control systems on operators, a limitation of their monopoly conditions, and an increase in the level of transparency of the actions implemented by them.

Other types of arguments focus on the study of the “incentives” to carry out corrupt acts. As these are inevitably correlated to the characteristics of the environmental and organizational context, one needs to consider how they, therefore, “interact” with the characteristics of organizational actors and that can be at the base of their corrupt behavior. In particular, two arguments can be distinguished.

First, with reference to the external context of the individual firm, beyond the aforementioned spaces of “opportunity” that may be created by environmental features such as turbulence and munificence, as well as low rivalry intensity or complex and ambiguous characteristics or newly enacted legislation, other two main factors of “environmental” origin are identified as underlying corruption risk (Baucus, 1994): (a) the “pressure” to which the company is subjected, due not only to elements of fore competitiveness of the markets but also to the possible scarcity of available resources or to a regulatory framework in constant evolution; (b) a “predisposition,” deriving from a context with a significant and consolidated level of illegality.

Second, with reference to the internal context of the individual company, some pioneering contributions (i.e., Albrecht et al., 1984) have gradually developed the original model of Cressey, precisely focusing on the formal and informal dimensions of work organization, investigating not only organizational structures and processes but also operating systems and the social and cultural dimensions of the organization, as possible determinants of individual behavior (Palmer, 2012). This allows the study of whether they could alternatively push individuals toward wrongdoing (i.e., the need to guarantee a certain level of performance) or “justify” corrupt behavior, whether in response to corporate interests or interests of an individual nature (Hinna et al., 2016; Palmer, 2012).

Therefore, through the combination of economic, social and psychological theories and perspectives, the set of contributions provided to date in the literature allows for an integrated view for understanding corruption, which is not limited to the analysis of only individual factors but expands to both the relationship between the individual and organizations, and between the organization and the context in which the company operates (Fig. 1).

Source: Hinna et al., (2016, p.155)

Environment (macro), organization (meso), and individual (micro) relationship: the integrated model of organization corruption determinants.

Major Streams in Corruption Prevention research

The analysis of the results that emerged in the literature review allows us to make several considerations on how the research overcomes the traditional repressive approach to corruption to adopt a more preventive one. We begin with describing a few general patterns found in the articles reviewed and proceed then to a more detailed discussion of three main themes which are related to (i) the attempts to generate more transparency at the macro-level, (ii) identification of initiatives at the organizational level that complement transparency enhancing measures and (iii) micro-level individual processes with relevance for preventing corrupt behavior.

Major Patterns Observed in the Literature

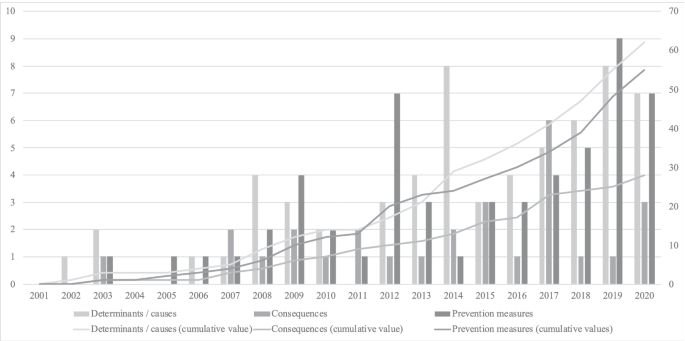

Reviewing the articles included, first we find that studies analyzing corruption have significantly increased during the period under analysis (2001–2020). More specifically, out of the 118 works examined, 82 percent of the publications were published in the last ten years (2010–2020) (Fig. 2).

The second consideration is that the research interest has progressively turned to the theme of corruption prevention. This is already evident by observing the number of papers dedicated explicitly to preventive measures. But it is further confirmed by the papers dedicated to the causes of corruption, as a typical object of investigation for the choice and evaluation of prevention strategies. However, although the combination of studies dealing with the causes and preventive measures of corruption increasingly outweighs studies focusing on its consequences over time, it is worth noting that the relationship between causes and related anti-corruption measures is still rarely discussed. This is particularly evident in studies focusing predominantly on one or the other aspect. In fact, only 20 works in our sample investigate both the causes and the related preventive measures, realizing an effective contextualization of the proposed measures against the identified causes.

A third element that stands out concerns the methodological perspective. Our research shows that most works adopt empirical approaches of which 58 percent (69 studies) qualifies as quantitative work, whereas 24 percent (28 studies) qualifies as qualitative work. Only 16 percent of articles (19 studies) are conceptual in nature or qualify as some form of review (2 percent, 2 studies). As corruption is notoriously difficult to observe, it is not surprising that quantitative studies rely primarily on country rankings based on international corruption indices such as the Transparency International Corruption Index or World Governance Indicators. At the same time, it is worth noting the unexpected predominance of quantitative studies in a field of research that does not yet present consolidated theoretical and explanatory models.

A fourth consideration is related to the alignment of the emerging literature adopting the preventive approach with the fundamental principles of the Merida Convention, which also highlights the adoption of measures aimed at avoiding the occurrence of corrupt behaviors in the organizational context. Indeed, the primary level of analysis adopted by the studies: 53 percent of the studies analyzed (63 studies) indicate that academic interest is moving towards a meso level of analysis, thus responding to the demand for studies that go beyond the macro-level (52 studies, 44 percent) to investigate organizational and behavioral aspects related to corruption (Jain, 2001). The meso-level analysis is mainly adopted by studies addressing the causes of corruption and the related measures (see Table 1 below).

More specifically, according to the key principles of the Merida Convention and consistent with distinct levels of analysis, some dominant themes emerge in the specialized literature: transparency and accountability strategies, human resource management (HRM) system, individual attitudes, and behaviors.

Finally, it is noteworthy that only one paper investigates a prevention system based on a “risk-based” approach (Van der Wal et al., 2016). Using data from 36 Victorian (Australia) public sector bodies the authors examined public officials' perceptions and the ability to identify and analyze corruption risks, the strategies to mitigate these risks, and the integrity mechanisms in place (Van der Wal et al., 2016).

Addressing Corruption through Transparency

At a macro level of analysis, one of the dominant themes is undoubtedly centered on the concepts of transparency and openness and how they in turn contribute to tackling corruption in the public sector with its promise to increase the chances of accountability. Transparency and anti-corruption policies have experienced a rapid spread worldwide – from the dramatic increase of freedom of information laws to the recent Open Government Partnership.

One example addressing the transparency argument is the work by Escaleras et al. (2010) asking if freedom of information acts have been an effective measure against corruption. Their findings do not support the effectiveness of freedom of information laws as a deterrent to corruption and remain neutral. But they support a moderating effect of institutional quality. They even find an increase in corruption for developing countries in the presence of freedom of information legislation. Hence, they conclude that freedom of information acts might be a small complementary measure in anti-corruption campaigns.

In contrast, in a study with a sophisticated empirical design de Simone et al. (2017) show that increasing fiscal transparency is an effective measure in the fight against corruption. Similarly, using data from the World Values Survey, Capasso et al. (2021) support the view that transparency creates incentives for individuals to be rule compliant and thus is an effective anti-corruption measure. Global pressure has played a significant role in policy dissemination and in some cases has also created an external pressure for legitimacy that has empowered domestic policymakers and facilitated the related adoption processes (Schnell, 2015).

However, the beneficial effect of government transparency may be contingent on the nature of the demand for accountability, as well as on a series of "heroic assumptions" (Fukuyama, 2015, p. 16) about the nature of stakeholders' willingness and ability to act upon the information received (Bauhr & Nasiritousi, 2012; Kolstad & Wiig, 2009). With their empirical research in public procurement, Bauhr et al. (2020) contribute to this debate with two significant elements. The first is the need to develop a theoretical distinction between ex-ante and ex-post transparency, the second is to consider the fact that the mere publication of relevant information is not enough for holding governments to account, as the legal and technical complexity of data presents substantial barriers to data use. Ayhan and Üstüner (2015) study reforms on public procurement in Turkey. While the initial aim of creating a more transparent public procurement system triggered the process, their analysis reveals an overall quality decline in the Turkish procurement system. One reason they identify is the dilution due to an increase in regulations (i.e., they report that about 20 amendments have been made to the original regulation) thereby creating untransparent rules, procedures, and regulations undermining anti-corruption efforts.

Often the need to build a transparent procurement environment inevitably passes through the adoption of technologically innovative solutions, such as e-procurement platforms (Liao et al., 2003). Understandably, the adoption of an innovative e-government approach should not be seen as a panacea for corruption problems in public organizations. A recent work by Wu et al. (2020) examines the potential and limitations of using e-government as an innovative anticorruption measure from the perspective of public officials in China and India, verifying that the effectiveness of this measure varies based on the political, economic, and cultural conditions of a country.

However, the implementation of an e-governance system is not only associated with the issue of transparency but—more generally—with the second important research stream identified at a macro level: good governance as a corruption prevention tool. In this sense, using cross-national secondary data from 191 countries, Chen and Aklikokou (2021) demonstrate a positive association between e-governments’ development and government effectiveness, as well as between e-governments’ development and their control of corruption.

In the same research field, the focus is often aimed at evaluating the degree to which public administration reforms contribute to corruption reduction (Andrei et al., 2009; Matei & Matei, 2009; Neshkova & Kostadinova, 2012; Segal & Lehrer, 2012). Other works take into consideration more specific reform processes, such as the adoption of quality public sector accounting (Lewis & Hendrawan, 2020) or auditing practices (Gustavson and Sundström, 2018) that can assist in reducing corruption. Similarly, Christensen and Fan (2018) report on the introduction of an anti-corruption campaign in China characterized by strict reporting rules between local and central governments. Such reporting rules discourage supervisors from covering up lower-level employees' misbehavior, hence increasing transparency. But Christensen and Fan (2018) also acknowledge the limitations of such institutional measures by highlighting that also deeply ingrained cultural attitudes need to be changed. They see the anti-corruption campaigns as a vehicle to do so.

Addressing Corruption through the HRM System

An HRM system integrates practices of pay and reward, recruitment, selection, training and development, career progression and related HRM practices. Berman (2015) offers a detailed discussion on how HRM can support efforts to fight corruption. Regarding the HRM system, several empirical studies have investigated the anti-corruption effect of the different HR practices. HRM efforts may also instill career commitment, loyalty and pride in serving the public. Therefore, highly selective recruiting procedures, appropriate onboarding and continuous training (Beeri et al., 2013) and socialization efforts may contribute to building a public sector workforce that is less inclined to engage in corrupt practices. In this sense, robust HRM systems act as an antidote to corrupt behavior (Berman, 2015). For example, looking at the recruitment of public officials in Denmark, Barfort et al. (2019) investigated whether a systematic self-selection of honest types into public service may be one channel that helps sustain a low level of corruption and found that dishonest individuals are more pecuniarily motivated and self-select out of public service and into higher-paying private-sector jobs.

A traditional argument in the corruption literature focuses on public officials’ compensation (inter alia, seminal work of Becker & Stigler, 1974). Higher salaries (compared to private sector salaries) that allow individuals to sustain their living costs are commonly seen as a deterrent to corruption. Individuals working under such conditions are simply less inclined to accept bribery payments or other gifts. While van Veldhuizen (2013) confirms this argument empirically in a laboratory experiment, showing that higher wages make individuals less corruptible, the broader review of the literature reveals a more nuanced picture. For example, setting up a theoretical model Macchiavello (2008) challenges the idea that the relationship between wages and corruption is monotonic. However, this study does not provide systematic empirical evidence to support the claim. In contrast, work by Chen and Liu (2018) and Dhillon et al. (2017) present empirical evidence on the wage argument. Chen and Liu (2018) study bribes received by Chinese officials based on court proceedings data and find a U-shaped relationship. Thus, according to their results, higher wages are effective when base salaries are low but increasing salaries as an anti-corruption measures loses its effectiveness when wages are at elevated levels already and when bribes can be negotiated. Results presented by Navot et al. (2016) who study a dataset consisting of 58 countries, highlight that higher wages may increase public corruption and demonstrate that people with a stronger sense of belonging tend to be less affected by pecuniary incentives. This finding is consistent with theories about intrinsic motivation.

Researchers have tested whether the relationship between performance rewards and corruption is conditioned by patronage-based recruitment (Campbell, 2020). They discover, through a comparison of over 100 countries, that the effect of pay on corruption is negative when clientelism is low but not significant or positive in countries where clientelism pervades the hiring process. On the same theme, Egeberg et al. (2019) oriented their studies to answer whether a system of recruitment based on merit enhances good and non-corrupt governance. In their case, the field of investigation was the European Union regulatory (decentralized) agencies and it emerged that these agencies seem to overwhelmingly apply meritocratic instruments when hiring people, regardless of their location.

Specific personnel management measures are also considered potential corruption prevention tools. For example, under the job rotation, public officials are less likely to accept bribes and this leads to less manipulated decision-making by public officials (Fišar et al., 2021). Also well-curated content for employee training may mitigate the corruption problem. For example, Luk (2012) recommends a three-pronged approach advocating the integration of ethical leadership, ethical training, and ethics legislation for maintaining the integrity of the civil service in Hong Kong.

Addressing Corruption by Influencing Individual Attitudes and Behaviors

Considering the results of the review, several authors have recently addressed the determinants of corruption at the individual level. Among others, Mangafić and Veselinović (2020) analyzed the effects of individual determinants on the likelihood of engaging in bribery, confirming that specific personal characteristics predicted corrupt behavior. Rabl (2011) explores the effect of contextual variables on the willingness of the individual to accept a bribe using laboratory experiments. Furthermore, Nichols and Robertson (2017) underscore the need to explore the role of moral emotions for bribery research. Another study demonstrated how dishonesty is strongly negatively correlated with public service motivation (Olsen et al., 2019).

The analysis of individual psychological determinants conducted by Kakavand et al. (2020) provided elements for HRM to understand workplace corruption better. The main results highlight that sense of mastery, distributive justice and procedural justice have a negative impact on workplace corruption, whereas powerlessness has a positive effect on workplace corruption. A further implication is that by staying in tune with motivational processes a HRM system is suited to prevent corrupt mechanisms fueled by frustrated or endangered motivational resources (Kakavand et al., 2020). Also Dhillon et al. (2017) offer a perspective based on psychological economics by applying a crowding-out logic (Frey et al. 2013) to explain the effects on bribe acceptance. In their theoretical model, they acknowledge the variety of individual motivational dispositions. Furthermore, they argue that concern for the collective reputation of the profession may be at play. They conclude that “optimal policies to reduce corruption should take account of the competing motivations for public sector work and the importance of maintaining a high status in the public sector as opposed to private sector work” (Dhillon et al., 2017, p.3).

The consideration of motivation also prompts thoughts on incentive systems in general. In a corrupt transaction both parties, e.g., a bribe-giver and a bribe-taker, are subject to different incentives to engage in the corrupt activity. Addressing this situation, some authors have argued that the nature of corruption is a decisive factor in determining such incentives. Capasso and Santoro (2018) distinguish between active (i.e., bargaining power to set bribe lies with the official) and passive (i.e., bargaining power lies with the private actor) corruption. Based on their empirical analyses, they recommend monitoring and strict supervision as more effective deterrents to active corruption whereas controls are more effective when fighting passive corruption.

Research further emphasized the impact on individual behaviors deriving from the adoption of codes of conduct or ethical leadership (Thaler and Helmig, 2016). In this empirical research carried out in Germany, it emerges that only ethical leadership has a positive effect on employees' organization-related attitudes. Consistently with this evidence, Janenova and Knox (2020) demonstrate how the introduction of specific ethics commissioners improves the benefits deriving from the adoption of the code of conduct in the context of Kazakhstan.

The encouragement of whistleblowing and protection of whistleblowers is the last dominant theme that emerged. A literature review published ten years ago on the wave of growing interest in the subject, despite the lack of empirical knowledge, discussed new theoretical and methodological areas of research in the domain of whistleblowing (Vadera et al., 2009).

As the decision to blow the whistle is rooted in the individual, the works analyzed in this review illustrates the interplay between the individual (micro), the organizational (meso) and the macro level. In order to encourage whistleblowing, both the organization and the legal system need to implement protection measures for the individuals involved. Hence, the literature reviewed highlights the complementary role organizations need to assume in anti-corruption initiatives as institutional measures may not be sufficient.

Following this path, recent studies have worked on: the content and effectiveness of whistleblowing policies (West and Bowman, 2020); the whistleblowing process, especially from a practitioner perspective (Vandekerckhove & Lewis, 2012); the organizational conditions necessary to encourage the whistleblowing (Previtali & Cerchiello, 2018), the determinants of a whistleblowing intention (Vadera et al., 2009; Cassematis & Wortley, 2013; Chang et al., 2017), and the influence of the ethical position on whistleblowing behavior in private and public contexts (Nayır et al., 2018). Noteworthy in this context is the work by Chang et al. (2017) on whistleblowing as it zooms in on the determinants of whistleblowing beyond mere institutional and regulatory protections. In their large-scale analysis of Korean public officials, they identify perceived colleague support and organizational support as significant antecedents to the willingness of individuals to blow the whistle in the presence of observed wrongdoing by others.

Instead of looking only into whistleblowing policies, organizations may also consider enforcement policies. For example, Burlando and Motta (2016) developed an anti-corruption enforcement model demonstrating that, within an optimal compensation scheme, legalization can play a critical anti-corruption role. In fact, they found that fiscal and legalization policies have an impact on reducing enforcement costs because they affect individual incentives to crime and corruption rents. Despite the model and the debate on the enforcement issue present at the global level, the two authors point out some significant limitations to this type of policies, in particular the negative implications on people’s trust, that could interpret the legalization as a repugnant policy.

Taking a similar perspective on enforcement, Capasso et al. (2019) analyzed a dataset on 80 countries to assess the relative effectiveness of various types of law enforcement, judicial efficiency and broader measures of related institutional quality, demonstrating that strengthening country-level institutions is the most powerful deterrent to corruption. The main and most interesting implication from this study is that “comprehensive improvements in enforcement involving better institutions related to law and order are more effective in combating corruption than focus on individual dimensions of enforcement” (Capasso et al., 2019, p. 357), hence stressing once again the need for a holistic approach to fight against corruption.

Future Research Agenda

This work reviewed the literature on public sector anti-corruption for upper-middle- and high-income countries. We assessed 118 studies identified by our search methodology according to a wide range of criteria, such as country of origin, methodological approach and its quality, level of analysis, scope, and anti-corruption approach, among others.

The problem of preventing corruption has long been an international political priority, and the need to activate policies of prevention, and not merely repression, of corruption is unequivocally present in both the UNCAC and the various control mechanisms, such as the Group of States against Corruption (GRECO) or the OECD’s Working Group on Bribery in International Business (WGB). As demonstrated by our review, the academic literature has responded to these demands and progressively focused its efforts on the prevention of corruption, which also highlights the adoption of measures aimed at avoiding the occurrence of corrupt behaviors in the organizational context.

Our research demonstrates an increasing adoption of the organizational level of analysis to investigate the determinants and the possible measures for corruption prevention and it outlines a new additional item which is the recognition of the individual as an essential element to explore both the causes and the specific measures which impact individual behaviors.

Concerning preventive measures, the study highlights a substantial alignment between the guidelines deriving from the Merida Convention and the dominant themes of interest in the academic debate, except for a lack of work on the risk-based approach to corruption prevention. From this vantage point, while corruption is increasingly considered a risk to public organizations’ performance (Power, 2007), the findings of the review suggest that little is known about the activities of various public organizations in promoting the logic of risk management or about the impact of these activities for administrations. This evidence is surprising as an exception to the importance that the management of risk has assumed a central role in public policy and management (i.e., Brown & Calnan, 2013; Hood et al., 2004; Miller et al., 2008) and raises some questions about the processes of analysis, evaluation and choice of prevention measures that, if not linked to an effective risk assessment, could be adopted in a standardized form.

From this point of view, there is a need to study risk management systems and processes for anti-corruption, also to better understand the link between causes and measures of corruption. Academic literature (Jain, 2001; Jancsics, 2019) and the international conventions stress the importance of linking the causes of corruption to the possible measures for formulating better policies and more effective identification of the appropriate recipe for the specific context. However, our review found that in academia, the alignment between causes and potential measures for combating corruption is still poorly investigated both at organizational and individual levels. This is particularly problematic as this missing link often hinders the effectiveness of anti-corruption policies with consequences on the interests and objectives of academic research as well as for theoretical or practical relevance.

Moreover, because of the nature of the research object and to build a plausible explanation for the causal relationship that links antecedents and countermeasures of corruption in specific organizational contexts, exploratory analyses are required (Benbasat et al., 1987). In this regard, the low number (and depth) of qualitative studies is surprising since the qualitative research methodology is beneficial in fields of study where it is still necessary to understand the studied reality, where consolidated theoretical and explanatory models cannot yet be found.

While the methodological challenges are severe, it is possible to overcome them. One issue lies in the hidden, invisible nature of corrupt activities which creates difficulties for empirical study. However, researchers can work on making it visible and it could be successful with regard to smaller payments, i. e. in the form of petty corruption. A case in point is the use of publicly available data that potentially makes corrupt activity visible and can be studied. For instance, Schoeneborn and Homberg (2018) exploited reports on a website to make small bribes visible. Another example is displayed in Bauhr et al. (2020) which presents an analysis based on publicly available information about public procurement tenders involving more than 100,000 observations. Corruption is made visible here by analyzing the number of participants in bids. Additional opportunities arise from the use of algorithms and computer science techniques that can identify hidden patterns through a combination of different databases, such as described in Velasco et al. (2021), who used data mining techniques to identify corruption risk patterns. As far as field studies are concerned, researchers can choose settings that allow them to make relevant observations such as Olken and Barron (2009) who studied more than 6000 illegal payments made by truck drivers to officials in Indonesia. Additionally, ethnographies or other forms of qualitative inquiry could help understand where institutional setups break down or which anti-corruption measures have design flaws. Therefore, overall, creative research designs can overcome some of the challenges that plague corruption research.

This literature review has provided a snapshot of the current state of the literature on corruption in upper-middle-income and high-income countries, highlighting future research needs to address. First, more attention to risk management processes is required; second, a stronger focus on the interrelationship between causes and solutions for corruption is needed; and third, more creative effort needs to be put into study design in order to generate solid evidence on corruption at the organizational and individual level. As the corruption literature grows further, we are confident that researchers will be able to address these challenges.

References

Aguirre, D. (2008). The human right to development in a globalized world. Routledge.

Albrecht, W. S., Howe, K. R., & Romney, M. B. (1984). Deterring fraud: the internal auditor’s perspective. Inst of Internal Auditors.

Anand, V., Ashforth, B. E., & Joshi, M. (2004). Business as usual: The acceptance and perpetuation of corruption in organizations. Academy of Management Perspectives, 18(2), 39–53.

Andrei, T., Matei, A. I., Tusa, E., & Nedelcu, M. (2009). Characteristics of the reforming process in the Romanian public administration system. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 25E, 13–31.

Anechiarico, F., & Jacobs, J. B. (1996). The pursuit of absolute integrity: How corruption control makes government ineffective. University of Chicago Press.

Argandoña, A. (2003). Private-to-Private Corruption. Journal of Business Ethics., 47, 253–267.

Auriol, E., & Blanc, A. (2009). Capture and corruption in public utilities: The cases of water and electricity in Sub-Saharan Africa. Utilities Policy, 17(2), 203–216.

Ayhan, B., & Üstüner, Y. (2015). Governance in public procurement: The reform of Turkey’s public procurement system. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 81(3), 640–662.

Barfort, S., Harmon, N. A., Hjorth, F., & Olsen, A. L. (2019). Sustaining honesty in public service: The role of selection. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 11(4), 96–123.

Baucus, M. S. (1994). Pressure, opportunity and predisposition: A multivariate model of corporate illegality. Journal of Management, 20(4), 699–721.

Bauhr, M., & Nasiritousi, N. (2012). Resisting transparency: Corruption, legitimacy, and the quality of global environmental policies. Global Environmental Politics, 12(4), 9–29.

Bauhr, M., Czibik, Á., de Fine Licht, J., & Fazekas, M. (2020). Lights on the shadows of public procurement: Transparency as an antidote to corruption. Governance, 33(3), 495–523.

Becker, G. S., & Stigler, G. J. (1974). Law enforcement, malfeasance, and compensation of enforcers. The Journal of Legal Studies, 3(1), 1–18.

Beeri, I., Dayan, R., Vigoda-Gadot, E., & Werner, S. B. (2013). Advancing ethics in public organizations: The impact of an ethics program on employees’ perceptions and behaviors in a regional council. Journal of Business Ethics, 112(1), 59–78.

Benbasat, I., Goldstein, D. K., & Mead, M. (1987). The case research strategy in studies of information systems. MIS quarterly, 11(3), 369–386. https://doi.org/10.2307/248684

Berman, E. M. (2015). HRM in development: Lessons and frontiers. Public Administration and Development, 35(2), 113–127.

Bicchieri, C., & Ganegoda, D. (2017). Determinants of corruption: A sociopsychological analysis. In Thinking about Bribery: neuroscience, moral cognition and the psychology of bribery. Cambridge University Press.

Bierstaker, J. L. (2009). Differences in attitudes about fraud and corruption across cultures: Theory, examples and recommendations. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal.

Brown, P., & Calnan, M. (2013). Trust as a means of bridging the management of risk and the meeting of need: A case study in mental health service provision. Social Policy & Administration, 47(3), 242–261.

Burlando, A., & Motta, A. (2016). Legalize, tax, and deter: Optimal enforcement policies for corruptible officials. Journal of Development Economics, 118, 207–215.

Campbell, J. W. (2020). Buying the honor of thieves? Performance pay, political patronage, and corruption. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 63, 100439.

Capasso, S., Goel, R. K., & Saunoris, J. W. (2019). Is it the gums, teeth or the bite? Effectiveness of dimensions of enforcement in curbing corruption. Economics of Governance, 20(4), 329–369.

Capasso, S., & Santoro, L. (2018). Active and passive corruption: Theory and evidence. European Journal of Political Economy, 52, 103–119.

Capasso, S., Cicatiello, L., De Simone, E., Gaeta, G. L., & Mourão, P. R. (2021). Fiscal transparency and tax ethics: Does better information lead to greater compliance? Journal of Policy Modeling, 45, 1031–1050.

Cassematis, P. G., & Wortley, R. (2013). Prediction of whistleblowing or non-reporting observation: The role of personal and situational factors. Journal of Business Ethics, 117(3), 615–634.

Castro, A., Phillips, N., & Ansari, S. (2020). Corporate corruption: A review and an agenda for future research. Academy of Management Annals, 14(2), 935–968.

Chang, Y., Wilding, M., & Shin, M. C. (2017). Determinants of Whistleblowing Intention: Evidence from the South Korean Government. Public Performance and Management Review, 40(4), 676–700. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2017.1318761

Chen, L., & Aklikokou, A. K. (2021). Relating e-government development to government effectiveness and control of corruption: a cluster analysis. Journal of Chinese Governance, 6(1), 1–19.

Chen, Y., & Liu, Q. (2018). Public-sector wages and corruption: An empirical study. European Journal of Political Economy, 54, 189–197.

Christensen, T., & Fan, Y. (2018). Post-New Public Management: A new administrative paradigm for China? International Review of Administrative Sciences, 84(2), 389–404.

Cressey, D. R. (1953). Other people's money: A study of the social psychology of embezzlement. New York: Free Press.

De Simone, E., Gaeta, G. L., & Mourão, P. R. (2017). The Impact of Fiscal Transparency on Corruption: An Empirical Analysis Based on Longitudinal Data. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 17(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1515/bejeap-2017-0021

Dhillon, A., Nicolò, A., & Xu, F. (2017). Corruption, intrinsic motivation, and the love of praise. Journal of Public Economic Theory, 19(6), 1077–1098.

Dimant, E., & Schulte, T. (2016). The nature of corruption: An interdisciplinary perspective. German Law Journal, 17(1), 53–72.

Dimant, E., & Tosato, G. (2018). Causes and effects of corruption: what has past decade's empirical research taught us? A survey. Journal of Economic Surveys, 32(2), 335–356.

Disch, A., Vigeland, E., Sundet, G., & Gibson, S. (2009). Anti-corruption approaches: A literature review. Oslo: Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation. Retrieved August, 12, 2018.

Egeberg, M., Gornitzka, Å., & Trondal, J. (2019). Merit-based recruitment boosts good governance: How do European Union agencies recruit their personnel? International Review of Administrative Sciences, 85(2), 247–263.

Escaleras, M., Lin, S., & Register, C. (2010). Freedom of information acts and public sector corruption. Public Choice, 145(3–4), 435–460.

Farrington, D. P., Gottfredson, D. C., Sherman, L. W., & Welsh, B. C. (2003). The Maryland Scientific Methods Scale. In Evidence-based crime prevention (pp. 27–35). Routledge.

Fišar, M., Krčál, O., Staněk, R., & Špalek, J. (2021). Committed to Reciprocate on a Bribe or Blow the Whistle: The Effects of Periodical Staff-Rotation in Public Administration. Public Performance & Management Review, 44(2), 404–424.

Frey, B., Homberg, F., & Osterloh, M. (2013). Organizational control systems and pay-for-performance in the public service. Organization Studies, 34, 949–972.

Fukuyama, F. (2015). Why is democracy performing so poorly? Journal of Democracy, 26(1), 11–20.

Graycar, A., & Monaghan, O. (2015). Rich country corruption. International Journal of Public Administration, 38(8), 586–595.

Gupta, S., Davoodi, H., & Alonso-Terme, R. (2002). Does corruption affect income inequality and poverty? Economics of Governance, 3(1), 23–45.

Gustavson, M., & Sundström, A. (2018). Organizing the audit society: Does good auditing generate less public sector corruption? Administration & Society, 50(10), 1508–1532.

Hall, R. E., & Jones, C. I. (1999). Why do some countries produce so much more output per worker than others? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(1), 83–116.

Hinna, A., Monteduro, F., & Moi, S. (2016). Organizational Corruption in the Education System. Dark Sides of Business and Higher Education Management, II, 2.

Hinna, A., Homberg, F., Ceschel, F. (2018). Anticorruption Reforms and Governance. In: Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance Living Edition, Month 1, p. 1-8.

Homer, E. M. (2020). Testing the fraud triangle: A systematic review. Journal of Financial Crime, 27(1), 172–187. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-12-2018-0136

Hood, C. C., James, O., Peters, G., & Scott, C. (2004). Controlling Modern Government: Oversight, competition, mutuality and randomness in three public policy domains. Edgar Elgar.

Hopkin, J. (2002). States, markets and corruption: A review of some recent literature. Review of International Political Economy, 9(3), 574–590.

Huber, W. D. (2017). Forensic accounting, fraud theory, and the end of the fraud triangle. Journal of Theoretical Accounting Research, 12(2), 28–49.

Jain, A. K. (2001). Corruption: A review. Journal of Economic Surveys, 15(1), 71–121.

Jancsics, D. (2019). Corruption as resource transfer: An interdisciplinary synthesis. Public Administration Review, 79(4), 523–537.

Janenova, S., & Knox, C. (2020). Combatting corruption in Kazakhstan: A role for ethics commissioners? Public Administration and Development, 40(3), 186–195.

Johnston, M. (2005). Syndromes of corruption: Wealth, power, and democracy. Cambridge University Press.

Kakavand, B., Neveu, J. P., & Teimourzadeh, A. (2020). Workplace corruption: a resource conservation perspective. Personnel Review, 49(1), 250–264. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-08-2018-0303

Klitgaard, R. E., Abaroa, R. M., & Parris, H. L. (2000). Corrupt cities: a practical guide to cure and prevention. World Bank Publications.

Kolstad, I., & Wiig, A. (2009). Is transparency the key to reducing corruption in resource-rich countries? World Development, 37(3), 521–532.

Lange, D. (2008). A multidimensional conceptualization of organizational corruption control. Academy of Management Review, 33(3), 710–729.

Le, N. T., Vu, L. T. P., & Nguyen, T. V. (2021). The use of internal control systems and codes of conduct as anti-corruption practices: evidence from Vietnamese firms. Baltic Journal of Management, 16(2), 173–189. https://doi.org/10.1108/BJM-09-2020-0338

Lewis, B. D., & Hendrawan, A. (2020). The impact of public sector accounting reform on corruption: Causal evidence from subnational Indonesia. Public Administration and Development, 40(5), 245-254.

Liao, S. H., Cheng, C. H., Liao, W. B., & Chen, I. L. (2003). A web-based architecture for implementing electronic procurement in military organisations. Technovation, 23(6), 521–532.

Luk, S. C. Y. (2012). Questions of ethics in public sector management: The case study of Hong Kong. Public Personnel Management, 41(2), 361–378.

Macchiavello, R. (2008). Public sector motivation and development failures. Journal of Development Economics, 86(1), 201–213.

Mangafić, J., & Veselinović, L. (2020). The determinants of corruption at the individual level: evidence from Bosnia-Herzegovina. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 33(1), 2670–2691.

Matei, L., & Matei, A. I. (2009). Corruption in the Public Organizations-Towards a Model of Cost-Benefit Analysis for the Anticorruption Strategies. First Global Dialogue'Governing Good and Governing Well': The First Global Dialogue on Ethical and Effective Governance, 28–30.

Mauro, P. (1995). Corruption and Growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics., 110(3), 681–712.

McCusker, R. (2006). Review of anti-corruption strategies. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology (p. 75)

Meagher, P. (2004). Anti-corruption agencies: A review of experience. IRIS Center.

Miller, P., Kurunmäki, L., & O’Leary, T. (2008). Accounting, hybrids and the management of risk. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(7–8), 942–967.

Morales, J., Gendron, Y., & Guénin-Paracini, H. (2014). The construction of the risky individual and vigilant organization: A genealogy of the fraud triangle. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 39(3), 170–194.

Navot, D., Reingewertz, Y., & Cohen, N. (2016). Speed or greed? High wages and corruption among public servants. Administration & Society, 48(5), 580–601.

Nayır, D. Z., Rehg, M. T., & Asa, Y. (2018). Influence of Ethical Position on Whistleblowing Behaviour: Do Preferred Channels in Private and Public Sectors Differ? Journal of Business Ethics, 149(1), 147–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3035-8

Neshkova, M. I., & Kostadinova, T. (2012). The effectiveness of administrative reform in new democracies. Public Administration Review, 72(3), 324–333.

Nichols, P. M., & Robertson, D. C. (Eds.). (2017). Thinking about bribery: Neuroscience, moral cognition and the psychology of bribery. Cambridge University Press.

OECD. (2000). Trust in Government Ethics Measures in OECD Countries. Paris: OECD

OECD. (2008). Specialised Anti-Corruption Institutions: Review of Models. Paris: OECD

Olken, B. A., & Barron, P. (2009). The simple economics of extortion: Evidence from trucking in Aceh. Journal of Political Economy, 117(3), 417–452.

Olsen, A. L., Hjorth, F., Harmon, N., & Barfort, S. (2019). Behavioral dishonesty in the public sector. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 29(4), 572–590.

Palmer, D. (2012). Normal organizational wrongdoing: A critical analysis of theories of misconduct in and by organizations. Oxford University Press on Demand.

Patton, M. Q. (1999). Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Services Research, 34(5 Pt 2), 1189.

Power, M. (2007). Organized uncertainty: Designing a world of risk management. Oxford University Press on Demand.

Previtali, P., & Cerchiello, P. (2018). The determinants of whistleblowing in public administrations: An analysis conducted in Italian health organizations, universities, and municipalities. Public Management Review, 20(11), 1683–1701. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1417468

Rabl, T. (2011). The impact of situational influences on corruption in organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 100(1), 85–101.

Rose-Ackerman, S. (1997). The pursuit of absolute integrity: How corruption control makes government ineffective. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management: The Journal of the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management, 16(4), 661–664.

Schnell, S. (2015). Mimicry, persuasion, or learning? The case of two transparency and anti-corruption policies in Romania. Public Administration and Development, 35(4), 277–287.

Schoeneborn, D., & Homberg, F. (2018). Goffman’s return to Las Vegas: Studying corruption as social interaction. Journal of Business Ethics, 151(1), 37–54.

Segal, L., & Lehrer, M. (2012). The institutionalization of stewardship: Theory, propositions, and insights from change in the Edmonton public schools. Organization Studies, 33(2), 169–201.

Suh, I., Sweeney, J. T., Linke, K., & Wall, J. M. (2020). Boiling the frog slowly: The immersion of C-suite financial executives into fraud. Journal of Business Ethics, 162(3), 645–673.

Tanzi, V. & Davoodi, H. (1997). Corruption, Public Investment, and Growth. International Monetary Fund Working Paper, 97/139.

Thaler, J., & Helmig, B. (2016). Do codes of conduct and ethical leadership influence public employees’ attitudes and behaviours? An Experimental Analysis. Public Management Review, 18(9), 1365–1399.

Treisman, D. (2000). The causes of corruption: A cross-national study. Journal of Public Economics, 76(3), 399–457.

Triangulation, D. S. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41(5), 545.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2003). United nations convention against corruption. Retrieved March 1, 2022, from https://www.unodc.org/documents/treaties/UNCAC/Publications/Convention/08-50026_E.pdf

Vadera, A. K., Aguilera, R. V., & Caza, B. B. (2009). Making sense of whistle-blowing’s antecedents: Learning from research on identity and ethics programs. Business Ethics Quarterly, 19(4), 553–586. https://doi.org/10.5840/beq200919432

Van Der Wal, Z., Graycar, A., & Kelly, K. (2016). See no evil, hear no evil? Assessing corruption risk perceptions and strategies of Victorian public bodies. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 75(1), 3–17.

Van Veldhuizen, R. (2013). The influence of wages on public officials’ corruptibility: A laboratory investigation. Journal of Economic Psychology, 39, 341–356.

Vandekerckhove, W., & Lewis, D. (2012). The Content of Whistleblowing Procedures: A Critical Review of Recent Official Guidelines. Journal of Business Ethics, 108(2), 253–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1089-1

Velasco, R. B., Carpanese, I., Interian, R., Paulo Neto, O. C., & Ribeiro, C. C. (2021). A decision support system for fraud detection in public procurement. International Transactions in Operational Research, 28(1), 27–47.

Wei, S.-J., & Wu, Y. (2001). Negative Alchemy? Corruption, Composition of Capital Flows, and Currency Crises. Working Paper no. 8187, National Bureau for Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w8187

Wells, K., & Littell, J. H. (2009). Study quality assessment in systematic reviews of research on intervention effects. Research on social work practice, 19(1), 52–62.

West, J. P., & Bowman, J. S. (2020). Whistleblowing Policies in American States: A Nationwide Analysis. The American Review of Public Administration, 50(2), 119–132.

Wu, A. M., Yan, Y., & Vyas, L. (2020). Public sector innovation, e-government, and anticorruption in China and India: Insights from civil servants. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 79(3), 370–385.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi Roma Tre within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

Not required.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1.

Search procedure

1 Eligibility Criteria |

Articles eligible for the review must have any form of corruption (as suggested by UNCAC) as their substantial theme and as the primary dependent or independent variable of interest. Studies that used corruption only as a subsidiary issue or in the form of an example to illustrate a different point made are considered not meeting the eligibility criteria. Studies must also discuss, to a meaningful extent, either causes, consequences, and/or anti-corruption measures Additionally, eligible studies must deal with a public sector setting in their analyses and must be written in English. Finally, we only include works focusing on countries defined by the World Bank as upper-middle-income economies (with a GNI per capita between $4,046 and $12,535) and high-income economies (with a GNI per capita of $12,536 or more). We made this decision based on several considerations. As Graycar and Monaghan (2015, p. 587) assert, “corruption is different between countries with established democracies and those in a state of political-economic development or transition”. Consequently, anti-corruption measures should vary with the state of development in a given country. Hence, focusing our review on richer countries provides a purposeful grouping and can potentially deliver additional insights with regard to anti-corruption measures. Second, there are undeniable differences in the approach to corruption and especially in the prevention strategies across cultures (Bierstaker, 2009). Cultural differences in ethical perceptions mean that recommendations on how organizations can address this problem and make improvements to their anti-corruption programmes are developed considering the country and culture in which they operate. Moreover, as explained by the Merida Convention, the need to contextualize the international indications is also reflected in the analysis of the impacts and the implementation modalities made for homogeneous groups of countries |

2 Search Procedure |

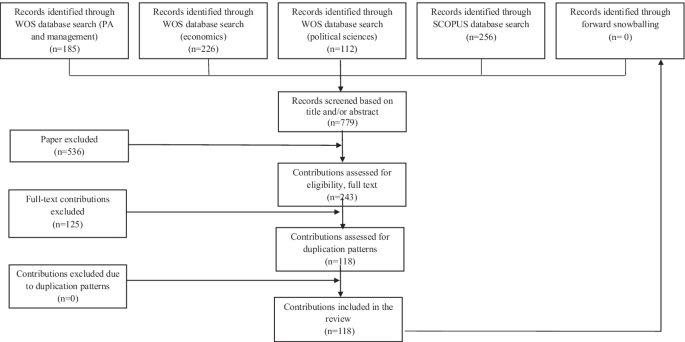

We searched the databases Web of Science and SCOPUS and did cross-checks using Google Scholar, i.e. we used reference lists of retrieved articles as starting points and looked for other studies that cited them. Additionally, to ensure that our focus is not only on articles registered in the web of science, we also browsed the book catalogues of primary academic publishing houses. Although this is not part of the systematic search it allowed us to reflect on contents of monographs and chapters from edited collections which complement the material published in academic journals The search period was 2001–2020, consistent with the renewed framework of policies and tools for corruption risk prevention defined by the preparatory works of the Merida Convention as well as aimed at reducing overlaps with the works reviewed in Jain (2001). We also checked for duplicates and removed them. In alignment with our focus on anti-corruption measures, we used the search string “corruption OR anti-corruption” combined with “public administration* OR public sector*” The initial search yielded 779 results. A screening of titles and abstracts led to the exclusion of 536 articles because these did not meet the selection criteria. Of the remaining 243, an additional 125 were excluded after reading the full text. Finally, we included 118 articles in our database |

3 Coding |

Subsequently, the authors coded studies in line with a set of relevant variables. Each author was assigned a set of articles to code independently. Critical or ambiguous cases were then discussed by the team to reach a decision. We coded the studies using the following criteria Country and country type. Many corruption studies operate on the country level or analyze country-level data for a range of countries. Therefore, we coded whether it was a multiple or single country study. In both cases, we recorded the country/countries covered in the study in a separate column. Additionally, it is common practice for authors to select subsets of countries. Thus, we coded whether the countries analyzed in a single study were developing or upper-middle-income economies Sector. The sector variable records that the study context is the public sector, taking a value of 0 otherwise Level of analysis. Here, we distinguish between macro-level and meso-level analyses. Macro-level analyses primarily comprise studies using country-level data. Meso-level studies are those in which organizations are the focus. Among those, we identified some that also featured micro-level analyses which focus on the individual Scope. Study scope was assessed by identifying the primary purpose of the study based on a) whether studies deal with the determinants/causes of corruption, b) whether a study’s focus was on the consequences of corruption, and c) whether studies discuss preventive measures Preventive approach. According to the principles emerging from the UNCAC, the indications of international organizations, and the suggestion coming from the academic literature we identified whether the approach to prevention is based on (a) the correlation between causes of corruption and preventive measures or (b) the risk approach Methodological approach. We classified the collected studies according to the methods used. Therefore, we distinguished between empirical-qualitative and empirical-quantitative studies. We further added two categories, conceptual and review, to appropriately reflect the range of studies found. Please note that three studies can also be classified also as “review” articles but have a much different focus3 Study quality. We decided to employ two different rating schemes, one for qualitative studies and one for quantitative studies, to derive a measure of the study’s empirical quality. For quantitative works, we used the Maryland Scale of Scientific Methods (Farrington et al., 2003), which rates quantitative empirical studies on a scale from 1 to 5 in which 1 indicates lowest quality and 5 indicates highest. The lowest quality includes correlational cross-sectional studies, whereas the highest quality is attributed to studies using methods characterized by random assignment and analysis of comparable units for treatment and comparison groups (see Wells & Littell, 2009, p. 55) For qualitative studies, we based the assessment on the criterion of triangulation which is crucial in such works. Following the principles described in Triangulation (2014) and Patton (1999), we adopted the following rating scale: (1) no triangulation; (2) triangulation of method or investigator or theory or data source; (3) multiple triangulation with two types of triangulation; (4) multiple triangulation with three triangulation types; and (5) multiple triangulation with four triangulation types. Again, 1 indicates lowest and 5 highest quality |

Appendix 2.

Summary of Search Procedures

The list of studies included in the review can be obtained from the authors upon request.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ceschel, F., Hinna, A. & Homberg, F. Public Sector Strategies in Curbing Corruption: A Review of the Literature. Public Organiz Rev 22, 571–591 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-022-00639-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-022-00639-4