Abstract

Although the similarity-attraction hypothesis (SAH) is one of the main theoretical foundations of management and industrial/organizational (I/O) psychology research, systematic reviews of the hypothesis have not been published. An overall review of the existing body of knowledge is therefore warranted as a means of identifying what is known about the hypothesis and also identifying what future studies should investigate. The current study focuses on empirical workplace SAH studies. This systematic review surfaced and analyzed 49 studies located in 45 papers. The results demonstrate that SAH is valid in organizational settings and it is a fundamental force driving employees’ behavior. However, the force is not so strong that it cannot be overridden or moderated by other forces, which includes forces from psychological, organizational, and legal domains. This systematic review highlights a number of methodological issues in tests of SAH relating to the low number of longitudinal studies, which is important given the predictive nature of the hypotheses, and the varying conceptualizations of attraction measurement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Individuals are positively inclined towards people who are similar to themselves. This simple but striking assertion underpins the similarity-attraction hypothesis (SAH), which frames much relationship and interpersonal attraction research (e.g., Byrne 1971; Montoya and Horton 2013). According to Byrne (1971), when people perceive themselves to be similar to other people, they experience positive feelings of attraction towards them. These similarities cover a large number of factors typically separated into demographic (e.g., race, gender, ethnicity, socio-economic background, and age) and psychological (e.g., personality, values, interests, religion, education, and occupation) divisions. Many studies have shown that similarities in these various forms lead to friendships and other close relationships (e.g., Graziano and Bruce 2008; Kleinbaum et al. 2013; McPherson et al. 2001; Riordan 2000).

In work settings, SAH is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it is a fundamental human drive that underpins effective social interaction in workplaces (e.g., McPherson et al. 2001; Montoya and Horton 2012), but on the other hand, it can lead to affinity or similarity bias and exclude those unlike the people making decisions (e.g., Björklund et al. 2012; Coates and Carr 2005; Hambrick 2007; O’Reilly et al. 2014; Sacco et al. 2003). To combat such ‘natural’ biases, most countries have passed laws to protect employees and potential employees who are dissimilar to those currently employed by organizations and who wield considerable power to decide who can enter organizations, who gets promoted, and how people are treated at work. Hence, within organizational settings, there is an eternal conflict at the heart of this field study; a conflict between natural human processes and natural justice.

In the mid 1990s, two reviews of work-related SAH appeared. An unpublished paper by Alliger et al. (1993) reviewed SAH in the context of personnel selection decision and work relations. Pierce et al. (1996) reviewed the hypothesis through the lens of romance in the workplace. There do not appear to be any more recent reviews and no broad-sweep reviews of SAH in the workplace. This paper makes a contribution by conducting such a study with the goal of reviewing extant knowledge on SAH in the workplace. Prior to a detailed account of the methods used for our systematic review, we first contextualize the current study by discussing relevant concepts and their evolution over time, namely the SAH and attraction, respectively. In our findings section, we review the cluster of studies providing empirical support for SAH, draw attention to measurement-design issues, and look at the study of SAH during the distinct organizational phases of recruitment and selection, employment, and organizational exit. In the discussion, we further the contribution of the paper with an examination of the paradox of similarity effects in an age when diversity and inclusion are prime considerations for organizations. We also draw out methodological challenges in the extant SAH in the workplace literature.

2 Similarity-attraction hypothesis

Although scientific focus on SAH gathered steam in the 1950s and 1960s (e.g., Byrne 1961; Festinger et al. 1950; Newcomb 1961; Walster et al. 1966), it has been studied for much longer. The relation between similarity and interpersonal attraction was mentioned as early as 1870 by Sir Francis Galton, who observed that illustrious men married illustrious women. Terman (1938) demonstrated that the greater the similarity between husband and wife, the more successful the marriage.

In the 1950s and 1960s, SAH studies focused on the interpersonal space and the role of attribution in attraction. In one of the first examples, Newcomb (1961) analyzed the establishment of friendships between new students at a college residence. He recorded students’ demographic information, attitudes, values, and beliefs and then measured their interpersonal attraction to each other. He showed that similarity between the students was the main predictor of attraction amongst them. Taking an experimental approach, Byrne and his colleagues used a “bogus stranger” methodology, in which they varied the similarity of a perceiver’s attitudes to those of a stranger, and then quantified the liking of that stranger. In a series of studies (e.g., Byrne 1971, 1997; Byrne and Blaylock 1963; Byrne and Clore 1967; Byrne and Nelson 1965), they demonstrated that attitude similarity delivered more liking of the target.

Byrne and Clore (1967) presented a reinforcement model to explain the positive relationship between similarity and attraction, in which similarity presents social validation of one’s views of the self and the world, thus helping to satisfy an individual’s needs. The positive influence that is caused by this need fulfillment becomes correlated with its source, namely the similar individual, and leads to their liking. As an alternative, dissimilarity jeopardizes epistemic needs (i.e., the desire for establishing understanding) as it challenges one’s views about the self and the world, and therefore stimulates negative affect that, in turn, becomes linked with the dissimilar person. Consequently, according to Byrne and Clore (1967), personal attraction is a conditioned reaction to the positive or negative effect that is created by an unconditioned similarity motivation.

While cognition was recognized as an essential aspect of shaping a judgment of another, the data indicated that the more attitudes individuals held in common with each other, the more attracted they were to the other person (Byrne 1971, 1997). This explains why people are attracted to like-minded individuals. Motivation to find others who are similar may have something to do with keeping a person’s perspective coherent with what they already know; people struggle for guaranteed certainty in dealing with the world around them (Byrne et al. 1966). Drawing on Newcomb (1956), Byrne (1997) argues that a key reason explaining the repeated support for SAH is due to the interpersonal rewards that follow from attraction: “At its simplest level, […] people like feeling good and dislike feeling bad” (Byrne 1997: 425). Further, assessments of similarity increase the validation of individuals’ values, which leads to attraction, harmony, and cooperation between individuals (Edwards and Cable 2009). Thus, the more similar people perceive themselves to be to each other, the more attractive they will be to each other.

Although most SAH studies have researched similarities in peoples’ attitudes, concluding that individuals are more attracted to people with whom they have many shared attitudes (Byrne 1961; Byrne et al. 1970; Kaptein et al. 2014), studies have found that actual similarity in external characteristics (e.g., age, hairstyle) is more predictive of attraction than similarity in psychological characteristics such as cleverness and confidence (Condon and Crano 1988; Duck and Craig 1975; Montoya et al. 2008). Amongst the demographic attributes most commonly studied are age, education, ethnic background, religious affiliation (Gardiner 2022; Grigoryan 2020), and occupation (Bond et al. 1968; Heine et al. 2009; Singh et al. 2008). A possible explanation for this is that external abilities can be more easily identified and measured. Nevertheless, there is also support for the SAH from studies of psychological similarity. These studies demonstrate that people are attracted to others on the perceived basis of shared attitudes (Newcomb 1961; Tidwell et al. 2013), personality traits (Griffitt 1966; Klohnen and Luo 2003), and values (Cable and DeRue 2002).

In addition to studies measuring the impact of actual similarity, scholars have also looked at the impact of perceived similarity. Many of these studies show that perceived similarities are better predictors of attraction than real similarities (Condon and Crano 1988; Montoya et al. 2008), but the impact of actual similarity–attraction is mainly restricted to interactions with associates or impressions of “bogus strangers” in laboratory settings (Sunnafrank 1992). Montoya et al. (2008) found a significant impact of actual similarity on attraction, while the strength of the attraction is highly connected to the interaction of the participants and targets (e.g., romantic partner, confederate, bogus stranger); these findings are typically interpreted to mean that demographic similarity information is a single source of information and that over time other information becomes more important than similarity-derived information.

The positive association of similarity to attraction can be explained by social cognition theory (Bandura 1991). According to this theory, people make sense of the world around them by gathering information in suitable cognitive classes or conceptual memory bins. This theory highlights how the role played by the categories of schemas, prototypes, and stereotypes biases decision-making reducing the accuracy and objectiveness of judgments (Fiske and Taylor 2008). For example, when people perceive someone who has grown up in the same neighborhood as themselves (same sport and school), it results in approval of them as they match a well-formed and well-understood stereotype in the person’s mind. The same person might be much less comfortable with someone from a different racial group or who comes from a completely different area since the appropriate cognitive ‘bin’ is still very immature and might even be distorted due to a few random encounters with similar stimuli. According to social cognition theory, people judge others not based on individual qualities, but rather on the stereotype held regarding that individual’s group membership (Kulik and Bainbridge 2006). Self-categorization theory builds on social cognition theory. It says that people assign people to ingroup and outgroup membership of prototypes. People are not thought of as unique individuals but rather as expressions of the relevant prototype, which is a process of depersonalization. Self-categorization theory suggests people classify their membership internally for themselves and others based on socially defined qualities (Turner and Chelladurai 2005). Individuals identify themselves and others into in-group and out-group (Hogg and Terry 2000) according to their preconceived notions of fit based on the following amongst other things: gender, age, race, organizational membership, and status (Turner and Chelladurai 2005).

3 Attraction

One of the vaguer elements in SAH is the definition of the word “attraction’. In the 1500s, the word ‘attraction’ was a medical phrase referring to the body’s tendency to absorb fluids or nourishment (Oxford English Dictionary 2013). Over time, the meaning of this word changed to the ability for an object to draw an object to itself, and then to the capability of a person to draw another person to him or her (Montoya and Horton 2014). Although there are a few studies that explore different definitions of the word, there is considerable variation in how it is conceptualized in SAH studies. Some studies emphasize the behavioral dimension (i.e., “drawing one to another,” Schachter 1959), other scholars highlight the emotion and affection (i.e., feeling positive towards another; e.g., Zajonc 1968), while others stress cognitive aspects (i.e., inferring positive attributes; e.g., Singh et al. 2007). Despite the variety, these all have positive connotations (Berscheid 1985; Huston and Levinger 1978). More recently, the literature has focused on the definition of attraction as an attitude, but limited the definition to an individual’s direct and positive emotional and/or behavioral response to a specific person (Montoya and Horton 2014). In this approach, the definition of attraction concentrates on the quality of someone’s emotional reaction to another person and a behavioral element that shows an individual’s tendency to act in a specific way to another (i.e., choosing to move closer to them). According to Montoya and Horton (2014: 60), “attraction is a person’s immediate and positive affective and/or behavioral response to a specific individual, a response that is influenced by the person’s cognitive assessments”. According to this point of view, the cognitive component is not considered part of attraction, but rather a process of forecasting an attraction reaction (Montoya et al. 2018).

Hence, the attraction literature has evolved different terms to describe the various attraction elements: affective attraction, behavioral attraction, and interpersonal attraction (or liking),Footnote 1 among other terms (Montoya and Horton 2020). Montoya et al. (2018) applied behavioral attraction to refer entirely to a self-reported preference for a certain behavioral reaction by using liking and interpersonal attraction to refer to an undifferentiated positive evaluation that comprises both affective and behavioral attraction. Reinforcing variation in definition of the word ‘attraction’, Montoya and Horton (2020) define attraction as an emotion that ranges from the professional, to the romantic, to the familial, meaning that attraction can be operationalized as an emotion in a wide range of settings (Montoya and Horton 2020).

4 Methodology

The goal of this study (Kuckertz and Block 2021) is to provide an overview of research findings on SAH as they relate to the workplace and, in particular, how they relate to interactions between people at work. To do this, we conducted a systematic review of SAH adopting the PRISMA (i.e., Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) approach (Caulley et al. 2020; O’Dea et al. 2021). We conducted a systematic review that looked for both empirical and theoretical papers published in refereed journals with JCR impact factors that investigate SAH. We only included papers written in English. As there had been no previous systematic reviews of SAH, no date limits were set.

4.1 Search methodology

4.1.1 Inclusion criteria

The following search terms were used to identify studies on SAH: ‘similarity-attraction’, ‘similarity attraction’, ‘similarity leads to attraction’, ‘similarity predicts attraction’, ‘similarity-interpersonal attraction’, ‘similarity to attraction’, ‘similarity/attraction’, ‘dissimilarity-repulsion’, ‘dissimilarity leads to repulsion’, ‘dissimilarity/repulsion’, ‘dissimilarity repulsion’, ‘Rosenbaum’s repulsion hypothesis’. Given the specific nature of these search terms, logical operators were used to find at least one of these terms in the titles, subjects, or abstracts of papers. For thoroughness, we included the reverse hypothesis, dissimilarity leads to repulsion (Rosenbaum 1986), in our search.

4.1.2 Exclusion criteria

As we employed relatively complex search strings such as ‘similarity-attraction’, exclusion criteria were not needed at the subject level.

4.1.3 Databases searched

The following databases were searched for articles on SAH: PsycInfo and PsycArticles, Web of Science, and Business Search Complete.

4.2 Search results

Table 1 presents the results of the initial trawl of the databases and shows how these 880 articles were filtered. Since the search yielded articles published before the onset of journal rankings and some journals have subsequently merged or ceased publishing, there were papers in the database that would have been excluded because of the evolution of the journal rather than due to their own inherent qualities. To avoid this, we decided to include any paper in a journal without a JCR impact factor that had been published before 2000 and had received 100 or more citations on Google Scholar. This resulted in five additional papers that otherwise would have been excluded from the dataset.

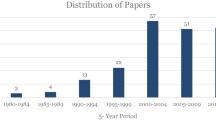

The final stage of filtering was to eliminate papers not located in organizational, business, or management settings in which similarity comparisons were based on staff-staff, staff-team members, staff-leaders, staff-managers, or staff-supervisors. This led to the removal of a further 275 studies and 8 more which were not empirical. 45 studies emerged containing four papers that featured two separate studies. The final database for this systematic review is therefore 45 papers containing 49 separate studies. Figure 1 shows the chronological distribution of the 45 workplace SAH articles in the dataset.

5 Results

Descriptive details and brief summaries of the 49 employee SAH studies surfaced in this systematic review are presented in Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8. They are placed in one of three categories. A total of 22 articles explore demographic similarity (Tables 2 and 3), 20 studies in 17 papers study psychological similarity (Tables 4 and 5), and seven studies in six papers investigate both psychological and demographic similarity (Tables 6 and 7). Demographic similarity involves the comparison of surface-level characteristics, such as gender, age, and race. They are permanent, usually observable, and easily measured (Harrison et al. 1998; Jackson et al. 1991). Psychological similarity involves deep-level attributes such as values, personality, attitudes, and beliefs (e.g., Engle and Lord 1997) and tend to be measured through direct assessment of self-reported perceptions.

5.1 Support for SAH

Just over half of the studies in the dataset yield empirical findings broadly in line with SAH predictions. These breakdown as follows: 11 demographic, 11 psychological, and 4 combined studies. In the demographic studies, similarity in gender, race, age, educational level, political affiliation have all been shown repeatedly to (1) positively associate with trust, job satisfaction, affective commitment, and in-role and extra-role performance, and selection decisions, and (2) negatively associate with staff turnover and related exit outcomes. In the psychological similarity studies, a matching pattern of results can be observed when similarity involves personality, emotional intelligence, and leadership and cognitive style. Such studies demonstrate that the SAH applies as much in organizational settings as it does in other settings. Rather, it is the studies that produce contradictory and asymmetric results that provide a more nuanced understanding of how SAH applies in these settings, particularly in studies of demographic similarity.

For example, Geddes and Konrad (2003) demonstrated a complex set of results in terms of race and performance feedback. They showed that both white and black employees responded more favorably to performance feedback from white managers demonstrating that SAH interacts with effects from other theories; in this case, status characteristics theory (Ridgeway 1991; Ridgeway and Balkwell 1997; Webster and Hysom 1998). Goldberg (2005) demonstrated a contrarian finding. Both male and female interviewers favored applicants on the opposite sex, which is better explained by social identity theory (Gaertner and Dovidio 2000) than SAH. Chatman and O’Reilly (2004) demonstrated that women reported a greater likelihood of leaving homogenous groups (i.e., groups comprising members of the same gender) than men, suggesting that other factors are in-play such as status conflict (Carli and Eagly 1999; Pugh and Wahrman 1983). It seems that SAH may be an underlying and natural driver of human behavior, but it is not such a dominant force in organizational settings that it cannot be moderated or eliminated by alternative forces. Although studies have shown that competing forces can influence the emergence of SAH effects, research is needed to understand the causes, circumstances, and conditions that give rise to this submergence. When and why does the SAH not appear in organizational settings?

5.2 What is attraction?

In these studies, there is considerable variation in the ways that attraction has been defined and conceptualized. Examples of the three different definitions of attraction – affective attraction, behavioral attraction, and interpersonal attraction – could be found in the dataset. Very few of the ways in which attraction has been measured might be regarded as direct measurement of attraction. They may be influenced by attractiveness, but most constructs used as interpretations of attraction in these studies are implicit and (at least) one step away from direct and isolated measures of attractiveness. For example, constructs like affective and normative commitment, perceived trustworthiness of managers, reaction to performance feedback, and organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs) may all be associated with feeling closer (affective attraction), moving closer (behavior attraction), or liking, but many other factors are simultaneously in play and at the very least require some explanation as to the reasons why and how they relate to attraction. Even the more direct conceptualizations like organizational attractiveness or selection outcomes are confounded by other factors such as the scant and managed information typically available during recruitment and selection processes (Billsberry 2007a; Herriot 1989) and other factors influencing attractiveness choices, such as the need to find a job (Billsberry 2007b). Overall, one of the biggest weaknesses in tests of SAH in organizational settings is the way that attractiveness has been conceived. An analysis of attraction conceptualizations can be found in Table 8.

Another noteworthy feature of the constructs used to capture attraction is the infrequency of repetition. Other than selection outcomes (of various sorts), perceptions of leadership, and OCBs (which have quite a tenuous association with attraction as there are many and varied reasons why people might engage in extra-role activities), most of the other constructs feature in just one study, occasionally two. This creates a sense that the field is still in an exploratory mode scoping out relevant relationships. Replication studies would provide confidence in these original findings and bring robustness. Further, there is a danger that the inclusiveness of constructs to represent attraction risks reifying the term. A challenge with such reification is that “scholars unknowingly integrate findings from studies with inconsistent construct definitions, which can create serious threats to validity” (Lane et al. 2006: 835). To avoid this, construct clarity is essential and an important precondition of theory testing (Fisher et al. 2021).

5.3 Measurement and design issues

Most work on SAH has been conducted outside of organizations. Our initial searches of these databases generated 880 journal articles of which only 45 were empirical studies in which the participants were workers and data was collected from them or about them. At the fringes of eligibility, we included analyses of the gender composition of top management teams (TMTs) and members of unions. We also included policy capturing studies that involve employees undertaking some type of experiment to find out what they would do in circumstances relevant to their jobs. But we excluded student samples even when they were performing a work-related task as students are too far detached from the reality of work. Our sample was also limited to studies that set out to examine the SAH rather than studies that adopted a SAH to test other relationships, such as value congruence studies (e.g., Cable and DeRue 2002). As such, the studies in the present paper typically employed a design in which a similarity independent variable (IV) predicted (or, more commonly, as a result of the dominance of cross-sectional designs, was associated with) an attractiveness dependent variable (DV). This IV → DV relationship was predicted and used to design the empirical study, which was tested with a variation of it (i.e., different types of similarity or attraction variable), typically with moderators or mediators. As such, similarity is viewed as the fundamental driver of effects and there is an absence of studies exploring why similarity is important to people in workplaces.

This dataset is dominated by cross-sectional (13 demographic (59%), 11 psychological (55%), and 4 combined (57%)) studies, which is counter-intuitive given the inherently predictive nature of the SAH (i.e., similarity leads to attraction). Testing the IV and DV at the same time makes the predictive element of the hypothesis unproven. Cross-sectional designs can, at best, show an association of the two constructs and only imply a predictive relationship (Kraemer et al. 2000). To get around the confounds in cross-sectional designs, researchers have adopted (1) experimental designs (2 demographic (9%) and 6 psychological (30%)) that capture policy intentions of organizational members, (2) archival studies (6 demographic (27%), 1 psychological (5%), and 1 combined (14%)), which can capture the historical effects on staff turnover and recruitment of similarity, and (3) longitudinal designs (1 demographic similarity, 2 psychological similarity, and 1 combined study). The low number of longitudinal studies in this field clearly presents an opportunity for future research. Such studies could validate the findings of cross-sectional studies, test the predictive nature of the similarity → attraction relationship, and explore the influence of other factors upon it. In addition, longitudinal studies adopting repeated measure methodologies could test for bidirectional effects and look at the strength and duration of the effect; this latter point is important given that Rosenfeld and Jackson (1965) reported that personality similarity only influenced friendship in the 1st year of acquaintance suggesting that SAH influences the initiation of attraction, but not its long-term survival.

Almost all of the demographic similarity studies in this review operationalize their similarity variables in very stark categorical terms. Gender is male or female; race is skin color and/or ethnographic background. Similarity or difference is calculated as being on one of the predetermined categories. These singular categorizations present a simple view of gender, race, and other demographic similarities. An alternative approach is intersectionality (Crenshaw 1990), which argues that different aspects of a person’s identity intersect to influence behavior towards them. For example, to treat Black women like White women ignores many socio-cultural factors disadvantaging them (Wilkins 2012). Intersectional analysis could take demographic similarity into a cultural and political space where the purpose of studying demographic SAH is to highlight privilege, disadvantage, and discrimination (Tatli and Özbilgin 2012).

5.4 Recruitment and selection

Perhaps the greatest influence of SAH in organizational settings is in explaining recruitment and selection decisions. Various scholars (e.g., Riordan 2000; Schneider 1987) have argued that applicants are more attracted to, and more expected to choose to work for, an organization whose workforce has features similar to their own. For example, people may be more attracted to a company that recruits a group of employees who are racially like them, predicting that these workers share their values and attitudes (Avery et al. 2004). These predictions have been demonstrated to be accurate in several studies in this review. Roth et al. (2020) showed that candidates’ perceived similarity of their political affiliation influences employment decision-makers, which eventually resulted in liking and organizational citizenship behavior performance (i.e., an employee’s voluntary commitment to the organization beyond his/her contractually obligated tasks). Kacmarek et al. (2012) found that greater female presence on nominating committees subsequently led to increased female representation on company boards. Chen and Lin (2014) showed that recruiters’ perceptions of applicants’ similarity to them influenced selection decisions. However, some asymmetric findings have emerged. For example, while Goldberg (2005) demonstrated race similarity effects, she also noted that male recruiters have a preference for female applicants. But, by and large, these studies align with findings in the general recruitment and selection literature reporting that organizational recruiters favor applicants resembling themselves and this reinforces opportunity in organizations to groups of people who already enjoy employment positions there (Bye et al. 2014; Kennedy and Power 2010; Noon 2010; Persell and Cookson 1985; Rivera 2012). As a consequence, many countries have passed legislation to protect those disadvantaged by these processes, although such legislation mainly confines itself to surface-level demographic factors such as gender, race, and disability. Hence, the application of SAH to recruitment situations is challenging as it separates demographic and psychological similarity and is located behind a legal mask that probably suppresses its appearance.

5.5 Post-hire

During employment, SAH presents a paradox for organizations. On the one hand, employees like working with people like themselves and are more productive (Bakar and McCann 2014; Chatman and O’Reilly 2004). But, on the other hand, it creates employee homogeneity, which Schneider (1987) argues causes organizations to occupy a self-defeating and increasingly narrow ecological niche, and crystalizes disadvantage and discrimination (Dali 2018). Empirical studies included in this review demonstrate both sides of this paradox. Interestingly though, looking across the demographic and psychological similarity studies separately, we gained a sense that demographic similarity worked in the initial phases of relationships to bring people together (e.g., Rosenfeld and Jackson 1965) and during short engagements (e.g., during recruitment and selection and loan decisions) when demographic similarity aids decision-making when there is impoverished information. Psychological similarity works over more prolonged periods and therefore comes more to the fore in during long-term employment (e.g., Marchiondo et al. 2018; Sears and Holmvall, 2010).

One noticeable absence in the studies captured in this review are those that explore value congruence (e.g., Adkins et al. 1994; Billsberry 2007b; Chatman 1989, 1991; Meglino et al. 1992; Yu and Verma 2019). These studies compare the similarity of aspects of people at work, most typically work values, and explore the consequences. Work value congruence has been shown to lead to positive organizational outcomes such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment, decrease employee conflict and negatively related to intentions to leave and organizational exit (Hoffman and Woehr 2006; Jehn 1994; Jehn et al. 1997, 1999; Kristof-Brown and Guay 2011; Subramanian et al. 2022; Verquer et al. 2003), thereby supporting SAH. Conversely, value incongruence is associated with distancing outcomes such as feelings of not belonging or being unfulfilled, and organizational exit (Edwards and Cable 2009; Edwards and Shipp 2007; Follmer et al. 2018; Kristof-Brown et al. 2005; Vogel et al. 2016) thereby supporting DRH leading Abbasi et al. (2021) to suggest that value congruence and value incongruence, and therefore SAH and DRH, are two different forces. The non-appearance of these studies in the current review appears to stem from the way these value congruence studies are theoretically justified. Rather than being direct tests of SAH, they are one step removed and based on ideas of person-environment (PE) fit and person-organization (PO) fit. These theories are themselves grounded in SAH (e.g., Chatman 1989; Schneider 1987), but the field is sufficiently well developed as a branch of PE and PO fit that it is not necessary to refer back to the conceptual roots of the SAH. This is likely to be the case for many others forms of congruence and incongruence such as political ideology incongruence (e.g., Bermiss and MacDonald 2018) or personality congruence (Schneider et al. 1998).

5.6 Organizational exit

Perhaps the biggest surprise in this dataset is the almost complete absence of any SAH studies exploring the organizational exit phase of work as voluntary decisions to leave organizations is one of the clearest examples of employees’ behavioral distancing (i.e., moving apart). Furthermore, there is theory arguing (e.g., Schneider 1987) that when employees feel dissimilar to others, they leave organizations. As mentioned above, there are many studies in the value congruence, PE fit, and PO fit literatures that explore the effect of dissimilarity on organizational exit, but these are not positioned as direct tests of SAH and so did not appear in this review.

6 Discussion

This systematic review has shown that, by and large, SAH holds true in organizational settings; similarity leads to attraction. There are some contrarian and asymmetrical findings, but these typically occur when other theories interact with SAH. An example comes from Gaertner and Dovidio (2000) who showed that both male and female interviewers favored applicants of the opposite sex, which is better explained by social identity theory. Further, legal sanctions can influence the appearance of SAH during recruitment, selection, and other episodes. Consequently, SAH can be viewed as a strong underlying force driving employees’ natural behavior, but it is not so strong that it cannot be overcome by other forces.

In organizational settings, paradox surrounds the application of SAH. People have a natural tendency to want to be with people like themselves and, without other influence, will choose to recruit people like themselves. Moreover, they prefer working with people like themselves and are more productive doing so. But such behavior can be exclusionary, discriminatory, and inequitable. Most countries have laws protecting many different categories of people from disadvantageous behavior for this reason. Further, many, perhaps most, organizations have espoused values and adopt policies of equal opportunity and these policies police formal selection processes, performance appraisals, and promotion practices, and informal behavior between employees. Neo-normative organizations go further and espouse values celebrating diversity and inclusivity (Husted 2021). In such organizations, employees are encouraged to “just be yourself” (Fleming and Sturdy 2011: 178), although this does not extend to their natural tendency to want to associate with people like themselves and strict rules exist to ensure compliance (Fleming and Sturdy 2009). So, there are many rules and regulations in organizations protecting those who might be disadvantaged from people’s natural tendency to be attracted to people similar to themselves.

Organization-level analysis is missing from the studies included in this systematic review. Instead, all the studies are designed as individual-level studies where data for both IVs and DVs are gathered from or about individuals and the impact of similarity or dissimilarity for them. This aligns with traditions in industrial/organizational psychology (Schneider and Pulakos 2022), but although it sheds light on individual differences, it fails to explore the ramifications of similarity and dissimilarity for organizations. This is not an insignificant omission as theoretical work by Schneider (1987) argues that the similarity-attraction hypothesis is a powerful force creating and reinforcing the cultures of organizations that explains why organizations are different to each other even when in the same industry and location. Further, exploring the impact of individual-level processes at the level of the organization can test assumptions about the importance of individual-level effects for the organization. As Schneider and Pulakos (2022: 386) state, “[t]he problem lies in our tendency to assume that the characteristics that produce high-performing individuals and teams also yield high-performing organizations, without testing this as often as we could or should.” In short, the assumption that effects at the individual-level lead to effects at the organization-level is an ecological fallacy and there is a need to test the organizational impact, if any, of individual-level findings.

Similarly, this systematic review did not include any empirical studies of the dissimilarity-repulsion hypothesis (DRH; Rosenbaum 1986). Relevant search terms were included, but no empirical studies of DRH in workplaces were found. One possible explanation accounting for this gap is that researchers may have presumed that since this theory is the polar opposite of similarity-attraction theory, low similarly-attraction means high dissimilarity repulsion, so the testing of both hypotheses may have been viewed as unnecessary. Alternatively, the low number of studies of organizational exit, particularly voluntary turnover, the most natural and powerful repulsion outcome in organizational settings, in this dataset constrains the appearance of the DRH. Organizational exit is a large literature and dissimilarity and misfit are known to be drivers of these actions (e.g., Doblhofer et al. 2019; Jackson et al. 1991; Kristof-Brown et al. 2005), so the suggestion is, like with value congruence, that these studies are grounded on theories other than DRH. Another interesting problem with DRH is the use of the term repulsion, which hints at “abhorrence, loathing, disgust and hatred” (Abbasi et al. 2021: 9). In times when there is a strong skew towards positive psychology (Kanfer 2005), examining the darker side of organizational life is much less common. Nevertheless, these are the moments that have the most impact on people and deserve much greater scholarly attention.

In addition to the above, this systematic review has surfaced several key avenues for future research related to methodological advancement. The first notable weakness in the empirical papers reviewed on this topic is the absence of studies adopting a longitudinal design. This is particularly noteworthy because the similarity leads to attraction hypothesis is inherently predictive in nature. Cross-sectional studies can give a sense of associations between similarity and attraction constructs, but do not convince when applied to predictive hypotheses. Some authors (e.g., Bruns et al. 2008; Eagleson et al. 2000; Young et al. 1997) have circumvented this issue by adopting policy-gathering designs in which respondents give an opinion about what they would do in a particular situation, but the findings of such studies would carry more weight if they were followed up with empirical studies of what people actually do or did in such circumstances. In this literature, there is a tendency for each study to stand separate from the other studies almost as if each study was exploring the hypothesis in a particular aspect of workplaces for the first time. Such exploratory work is commendable, but there is a need for studies to replicate and integrate findings.

The second noticeable methodological weakness in these studies is the manner in which attraction outcomes have been defined. Decisions to join or leave organizations are the most obvious examples of behavioral attraction and repulsion (i.e., ‘moving to’ and ‘moving away’). However, even attraction and repulsion outcomes like these are rarely the exclusive consequence of similarity or dissimilarity, but they have the advantage of being clear movements into or out of organizations. Other behavioral outcomes used in these studies as measures of attraction include absenteeism, TMT homogeneity, diversity levels, advice-seeking, and small business loan decisions, which appear to show decreasing alignment to the notions of attraction or repulsion. The psychological interpretations of attraction are perhaps even further removed from direct definitions of the word. Many constructs have been used as the dependent variables ranging from job satisfaction, perceived PO fit, perceptions of the quality of LMX relationships, commitment to a trade union, reactions to incivility, and employee well-being. These are all important outcomes, but they are not necessarily capturing a sense of feeling closer to others. Only five studies in this sample collected attraction data based on interpersonal liking, relations, or friendship, which might be thought to be the most direct capture of attraction. As a result, the workplace SAH literature gives the impression of actually being a literature that has rigorously explored the impact of many different types of demographic and psychological similarity in organizations, but not necessarily in terms of how it predicts attraction and repulsion outcomes. Hence, there is a strong need for SAH studies that capture more direct measures of attraction and this could prove to be a fruitful avenue for future research.

Another methodological consideration centers on causation. All the studies reviewed in this review employed an IV predicts DV design where the IVs were a form of similarity or dissimilarity and the DVs were a form of attraction or repulsion. As the SAH was being tested, the natural assumption in these studies is that similarity itself is the driver of outcomes. This, of course, triggers questions about why similarity (or dissimilarity) might be driving outcomes. What is it about similarity that drives attraction outcomes? An unkind hypothesis might be that people are inherently racist, sexist, ageist, linguicist, and so forth, in which case management control strategies appear a natural response. A kinder hypothesis is that people feel less threat from people similar to themselves and have a greater sense of belonging amongst people similar to themselves, in which case strategies focused on improving integration appear appropriate. A more neutral hypothesis might be the similarity makes it easier to predict others’ behavior and brings expectations of reciprocity (Newcomb 1956), which would raise distributive justice concerns. At present, the SAH in the workplace literature talks little about why similarity drives attraction outcomes and instead tends to focus on whether it does lead to attraction. But as different organizational responses might be expected to follow different causations, it is important to explore the reasons why similarity (and dissimilarity) are having attraction (and repulsion) effects in workplaces.

6.1 Limitations

This systematic review was strictly limited to empirical studies that set out to test SAH (and DRH) in organizational settings. To be included in this systematic review, this intention needed to be stated in the title, abstract, or keywords through the mention of various words and phrases suggesting SAH. This approach means that there are likely to be many studies not included in this systematic review that might measure some form of human similarity and use it to predict some form of attraction. The most obvious examples are the various organizational fit literatures, the value congruence and incongruence literatures, the recruitment, selection, induction, and socialization literatures, and the organizational exit literature. In all these cases, there are theoretical foundations based on SAH or DRH, but these literatures take the SAH and DRH roots ‘as a given’ and have placed their own theoretical frameworks on them (Evertz and Süß 2017). For example, an empirical PO fit study, which has similarity assessments at its core, might refer to PE interactions as its theoretical base and not deconstruct this further to the underlying SAH. It seems a common theme in these fields; there is no longer feel the need to justify the study in terms of testing SAH or DRH and therefore these underpinning hypotheses are not mentioned in titles, abstracts, or keywords. Although considerable scholarly advantage would accrue from including these literatures in a systematic review of SAH and DRH, it would be a truly Herculean task as it would require reading literally thousands of papers without any search terms to guide the hunt for similarity IVs and attraction DVs.

7 Conclusion

This paper systematically reviewed empirical studies of the ‘similarity leads to attraction’ (SAH) and ‘dissimilarity leads to repulsion’ (DRH) hypotheses in organizational settings. A total of 49 studies in 45 separate papers were surfaced, which split roughly 50/50 into studies of demographic similarity and psychological similarity. The results of these studies confirm that SAH remains valid in organizational settings and that it is a fundamental force driving employees’ behavior. However, although similarity and dissimilarity drive attraction and repulsion outcomes, the force is not so strong that it cannot be overridden or moderated by other forces, which includes forces from psychological, organizational, and legal domains. This systematic review highlighted a number of methodological issues in tests of SAH relating to the low number of longitudinal studies, which is important given the predictive nature of the hypotheses, and the varying conceptualizations of attraction measurement. This study also demonstrated that paradox is at the heart of SAH in organizational settings.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The search terms used to gather data are detailed in the methodology section.

Notes

It should be noted that although Montoya and Horton (2020) categorize ‘liking’ as an element of interpersonal attraction, others have categorized it as an aspect of affective attraction. Differences relate to how ‘liking’ is conceptualized and measured in studies.

References

Avery DR, Hernandez M, Hebl MR (2004) Who’s watching the race? Racial salience in recruitment advertising. J Appl Soc Psychol 34:146–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02541.x

*Bacharach SB, Bamberger PA (2004) Diversity and the union: the effect of demographic dissimilarity on members’ union attachment. Group Org Manag 29:385–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601103257414

*Bagues MF, Esteve-Volart B (2010) Can gender parity break the glass ceiling? Evidence from a repeated randomized experiment. Rev Econ Stud 77:1301–1328. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-937X.2009.00601.x

*Bakar HA, McCann RM (2014) Matters of demographic similarity and dissimilarity in supervisor–subordinate relationships and workplace attitudes. Int J Intercultl Relat 41:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2014.04.004

Bandura A (1991) Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Org Behav Human Decis Process 50:248–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90022-l

*Bechtoldt MN (2015) Wanted: self-doubting employees—Managers scoring positively on impostorism favor insecure employees in task delegation. Pers Individ Differ 86:482–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.07.002

Bermiss YS, McDonald R (2018) Ideological misfit? Political affiliation and employee departure in the private-equity industry. Acad Manag J 61:2182–2209. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.0817

Berscheid ES (1985) Interpersonal attraction. In: Lindzey G, Aronson E (eds) Handbook of social psychology, vol 2. Random House, New York, pp 413–483

Billsberry J (2007a) Experiencing recruitment and selection. Wiley, Chichester

Billsberry J (2007b) Attracting for values: an empirical study of ASA’s attraction proposition. J Manag Psychol 22:132–149. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710726401

Björklund F, Bäckström M, Wolgast S (2012) Company norms affect which traits are preferred in job candidates and may cause employment discrimination. J Psychol 146:579–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2012.658459

Bond MH, Byrne D, Diamond MJ (1968) Effect of occupational prestige and attitude similarity on attraction as a function of assumed similarity of attitude. Psychol Rep 23:1167–1172. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1968.23.3f.1167

*Bruns V, Holland DV, Shepherd DA, Woklund J (2008) The role of human capital in loan officers’ decision policies. Entrep Theor Pract 32:485–506. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008.00237.x

Bye HH, Horverak JG, Sandal GM, Sam DL, van de Vijver FJR (2014) Cultural fit and ethnic background in the job interview. Int J Cross Cult Manag 14:7–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595813491237

Byrne D (1961) Interpersonal attraction and attitude similarity. J Abnorm Soc Psychol 62:713–715. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0044721

Byrne D (1971) The attraction paradigm. Academic Press, New York

Byrne D (1997) An overview (and underview) of research and theory within the attraction paradigm. J Soc Pers Relat 14:417–431. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407597143008

Byrne D, Blaylock B (1963) Similarity and assumed similarity among husbands and wives. J Abnorm Soc Psychol 67:636–640. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0045531

Byrne D, Clore GL (1967) Effectance arousal and attraction. J Pers Soc Psychol 6:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0024829

Byrne D, Nelson D (1965) Attraction as a linear function of proportion of positive reinforcements. J Pers Soc Psychol 1:659–663. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0022073

Byrne D, Clore GL, Worchel P (1966) The effect of economic similarity-dissimilarity on interpersonal attraction. J Pers Soc Psychol 4:220–224. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0023559

Byrne D, Ervin CR, Lamberth J (1970) Continuity between the experimental study of attraction and real-life computing dating. J Pers Soc Psychol 16:157–165. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0029836

Cable DM, DeRue DS (2002) The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. J Appl Psychol 87:875–884. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.87.5.875

Carli L, Eagly A (1999) Gender effects on social influence and emergent leadership. In: Powell GN (ed) Handbook of gender and work. Sage, Thousand Oaks, pp 203–222

Caulley L, Cheng W, Catalá-López F, Whelan J, Khoury M, Ferraro J, Moher D (2020) Citation impact was highly variable for reporting guidelines of health research: a citation analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 127:96–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.07.013

Chatman J (1989) Improving interactional organizational research: a model of person-organization fit. Acad Manag Rev 14:333–349. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4279063

Chatman JA (1991) Matching people and organizations: selection and socialization in public accounting firms. Adm Sci Q 36:459–484. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393204

*Chatman JA, O’Reilly CA (2004) Asymmetric reactions to work group sex diversity among men and women. Acad Manag J 47:193–208. https://doi.org/10.5465/20159572

*Chen CC, Lin MM (2014) The effect of applicant impression management tactics on hiring recommendations: cognitive and affective processes. Appl Psychol Int Rev 63:698–724. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12013

Coates K, Carr SC (2005) Skilled immigrants and selection bias: a theory-based field study from New Zealand. Int J Intercult Relat 29:577–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.05.001

Condon JW, Crano WD (1988) Inferred evaluation and the relation between attitude similarity and interpersonal attraction. J Pers Soc Psychol 54:789–797

Crenshaw K (1990) Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stan Law Rev 43:1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

Dali K (2018) Culture fit as anti-diversity Avoiding Human Resources decisions that disadvantage the brightest. Int J Info Divers Incl 2:1–8. https://doi.org/10.33137/ijidi.v2i4.32199

*Den Hartog DN, De Hoogh AHB, Belschak FD (2020) Toot your own horn? Leader narcissism and the effectiveness of employee self-promotion. J Manag 46:261–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318785240

*Devendorf SA, Highhouse S (2008) Applicant-employee similarity and attraction to an employer. J Occup Org Psychol 81:607–617. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317907X248842

Doblhofer DS, Hauser A, Kuonath A, Haas K, Agthe M, Frey D (2019) Make the best out of the bad: coping with value incongruence through displaying facades of conformity, positive reframing, and self-disclosure. Eur J Work Org Psychol 28:572–593. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2019.1567579

*Doms M, zu Knyphausen-Aufseß D (2014) Structure and characteristics of top management teams as antecedents of outside executive appointments: a three-country study. Int J Human Resour Manag 25(22):3060–3085. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.914052

Duck SW, Craig G (1975) Effects of type of information upon interpersonal attraction. Soc Behav Pers Int J 3:157–164. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.1975.3.2.157

*Eagleson G, Waldersee R, Simmons R (2000) Leadership behaviour similarity as a basis of selection into a management team. Br J Soc Psychol 39:301–308. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466600164480

Edwards JR, Cable DM (2009) The value of value congruence. J Appl Psychol 94:654–677. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014891

Edwards J, Shipp A (2007) The relationship between person-organization fit and outcomes: An integrative theoretical framework. In: Ostroff C, Judge TA (eds) Perspectives on organizational fit. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, pp 209–258

Engle EM, Lord RG (1997) Implicit theories, self-schemas, and leader-member exchange. Acad Manag J 40:988–1010. https://doi.org/10.2307/256956

Evertz L, Süß S (2017) The importance of individual differences for applicant attraction: a literature review and avenues for future research. Manag Rev Q 67:141–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-017-0126-2

Festinger L, Schachter S, Back K (1950) Social pressures in informal groups; a study of human factors in housing. Milbank Memorial Fund Q 30:384–387. https://doi.org/10.2307/3348388

Fisher G, Mayer K, Morris S (2021) From the editors—Phenomenon-based theorizing. Acad Manag Rev 46(4):631–639. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2021.0320

Fiske ST, Taylor SE (2008) Social cognition: From brains to culture, 3rd edn. McGraw-Hill, New York

Fleming P, Sturdy A (2009) “Just be yourself!: towards neo-normative control in organizations. Emp Relat 31:569–583. https://doi.org/10.1108/01425450910991730

Fleming P, Sturdy A (2011) ‘Being yourself’ in the electronic sweatshop: new forms of normative control. Human Relat 64:177–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726710375481

Follmer EH, Talbot DL, Kristof-Brown AL, Astrove SL, Billsberry J (2018) Resolution, relief, and resignation: a qualitative study of responses to misfit at work. Acad Manag J 61:440–465. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0566

Gaertner SL, Dovidio JF (2000) Reducing intergroup bias: The common ingroup identity model. Psychology Press, Philadelphia

Gardiner E (2022) What’s age got to do with it? The effect of board member age diversity: a systematic review. Manag Rev Q. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-022-00294-5

*Geddes D, Konrad AM (2003) Demographic differences and reactions to performance feedback. Human Relat 56:1485–1513. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267035612003

*Georgiou G (2017) Are oral examinations objective? Evidence from the hiring process for judges in Greece. Eur J Law Econ 44:217–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-016-9545-0

*Goldberg CB (2005) Relational demography and similarity-attraction in interview assessments and subsequent offer decisions - Are we missing something? Group Org Manag 30:597–624. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601104267661

*Graves LM, Powell GN (1988) An investigation of sex discrimination in recruiters’ evaluations of actual applicants. J Appl Psychol 73:20–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.73.1.20

Graziano WG, Bruce JW (2008) Attraction and the initiation of relationships: A review of the empirical literature. In: Sprecher S, Wenzel A, Harvey J (eds) Handbook of relationship initiation. Psychology Press, Philadelphia, pp 275–301. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429020513-24

Griffitt WB (1966) Interpersonal attraction as a function of self-concept and personality similarity-dissimilarity. J Pers Soc Psychol 4:581–584. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0023893

Grigoryan L (2020) Perceived similarity in multiple categorization. Appl Psychol Int Rev 69:1122–1144. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12202

Hambrick DC (2007) Upper echelons theory: an update. Acad Manag Rev 32:334–343. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.24345254

Harrison DA, Price KH, Bell MP (1998) Beyond relational demography: time and the effects of surface- and deep-level diversity on work group cohesion. Acad Manag J 41:96–107. https://doi.org/10.5465/256901

Heine SJ, Foster JAB, Spina R (2009) Do birds of a feather universally flock together? Cultural variation in the similarity-attraction effect. Asian J Soc Psychol 12:247–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-839x.2009.01289.x

Herriot P (1989) Selection as a social process. In: Smith M, Robertson IT (eds) Advances in selection and assessment. Wiley, Chichester, pp 171–187

Hoffman B, Woehr D (2006) A quantitative review of the relationship between person–organization fit and behavioral outcomes. J Vocat Behav 68:389–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.08.003

Hogg MA, Terry DJ (2000) Social identity and self-categorization processes in organizational contexts. Acad Manag Rev 25:121–140. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2000.2791606

Husted E (2021) Alternative organization and neo-normative control: notes on a British town council. Cult Org 27:132–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759551.2020.1775595

Huston TL, Levinger G (1978) Interpersonal attraction and relationships. Annu Rev Psychol 29:115–156. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.29.020178.000555

Jackson SE, Brett JF, Sessa VI, Cooper DM, Julin JA, Peyronnin K (1991) Some differences make a difference: individual dissimilarity and group heterogeneity as correlates of recruitment, promotions, and turnover. J Appl Psychol 76:675–689. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.76.5.675

*Jaiswal A, Dyaram L (2019) Towards well-being: role of diversity and nature of work. Emp Relat 41:158–175. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-11-2017-0279

Jehn KA (1994) Enhancing effectiveness: an investigation of advantages and disadvantages of value-based intragroup conflict. Int J Confl Manag 5:223–238. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb022744

Jehn KA, Chadwick C, Thatcher SM (1997) To agree or not to agree: The effects of value congruence, individual demographic dissimilarity, and conflict on workgroup outcomes. Int J Confl Manag 8:287–305. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb022799

Jehn KA, Northcraft GB, Neale MA (1999) Why differences make a difference: a field study of diversity, conflict, and performance in workgroups. Adm Sci Q 44:741–763. https://doi.org/10.2307/2667054

*Jiang CX, Chua RYJ, Kotabe M, Murray JY (2011) Effects of cultural ethnicity, firm size, and firm age on senior executives’ trust in their overseas business partners: evidence from China. J Int Bus Stud 42:1150–1173. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2011.35

*Kaczmarek S, Kimino S, Pye A (2012) Antecedents of board composition: the role of nomination committees. Corpor Gov Int Rev 20:474–489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2012.00913.x

Kanfer R (2005) Self-regulation research in work and I/O psychology. Appl Psychol Int Rev 54:186–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2005.00203.x

Kaptein M, Castaneda D, Fernandez N, Nass C (2014) Extending the similarity-attraction effect: the effects of when-similarity in computer-mediated communication. J Comput Med Commun 19:342–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12049

Kennedy M, Power MJ (2010) The smokescreen of meritocracy: elite education in Ireland and the reproduction of class privilege. J Crit Educ Policy Stud 8:222–248

*Klein KJ, Lim BC, Saltz JL, Mayer DM (2004) How do they get there? An examination of the antecedents of centrality in team networks. Acad Manag J 47:952–963. https://doi.org/10.5465/20159634

Kleinbaum AM, Stuart TE, Tushman ML (2013) Discretion within constraint: homophily and structure in a formal organization. Org Sci 24:1316–1336. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1120.0804

Klohnen EC, Luo S (2003) Interpersonal attraction and personality: what is attractive-self similarity, ideal similarity, complementarity or attachment security? J Pers Soc Psychol 85:709–722. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.4.709

Kraemer HC, Yesavage JA, Taylor JL, Kupfer D (2000) How can we learn about developmental processes from cross-sectional studies, or can we? Am J Psychiatry 157:163–171. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.163

Kristof-Brown AL, Guay RP (2011) Person-environment fit. In: Zedeck S (ed) APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, vol 3. American Psychological Association, Washington DC, pp 3–50. https://doi.org/10.1037/12171-001

Kristof-Brown AL, Zimmerman RD, Johnson EC (2005) Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: a meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Pers Psychol 58:281–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00672.x

Kuckertz A, Block J (2021) Reviewing systematic literature reviews: ten key questions and criteria for reviewers. Manag Rev Q 71:519–524. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-021-00228-7

Kulik CT, Bainbridge HT (2006) HR and the line: the distribution of HR activities in Australian organisations. Asia Pac J Human Resour 44:240–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/1038411106066399

Lane PJ, Pathak KBR, S, (2006) The reification of absorptive capacity: a critical review and rejuvenation of the construct. Acad Manag Rev 31:833–863. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.22527456

*Lau DC, Lam LW, Salamon SD (2008) The impact of relational demographics on perceived managerial trustworthiness: similarity or norms? J Soc Psychol 148:187–209. https://doi.org/10.3200/socp.148.2.187-209

*Liang HY, Shih HA, Chiang YH (2015) Team diversity and team helping behavior: the mediating roles of team cooperation and team cohesion. Eur Manag J 33:48–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2014.07.002

*Marchiondo LA, Biermeier-Hanson B, Krenn DR, Kabat-Farr D (2018) Target meaning-making of workplace incivility based on perceived personality similarity with perpetrators. J Psychol Interdiscip Appl 152:474–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2018.1481819

*Marstand AF, Epitropaki O, Martin R (2018) Cross-lagged relations between perceived leader–employee value congruence and leader identification. J Occup Org Psychol 91:411–420. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12192

McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook JM (2001) Birds of a feather: homophily in social networks. Annu Rev Soc 27:415–444. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415

Meglino BM, Ravlin EC, Adkins CL (1992) The measurement of work value congruence: a field study comparison. J Manag 18:33–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639201800103

*Mitteness CR, DeJordy R, Ahuja MK, Sudek R (2016) Extending the role of similarity attraction in friendship and advice networks in angel groups. Entrep Theor Pract 40:627–655. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12135

Montoya RM, Horton RS (2012) The reciprocity of liking effect. In: Paludi M (ed) The psychology of love. Praeger, Santa Barbara, pp 39–57

Montoya RM, Horton RS (2013) A meta-analytic investigation of the processes underlying the similarity-attraction effect. J Soc Pers Rel 30:64–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407512452989

Montoya RM, Horton RS (2014) A two-dimensional model for the study of interpersonal attraction. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 18:59–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868313501887

Montoya RM, Horton RS (2020) Understanding the attraction process. Soc Pers Psychol Compass 14:e12526. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12526

Montoya RM, Horton RS, Kirchner J (2008) Is actual similarity necessary for attraction? A meta-analysis of actual and perceived similarity. J Soc Pers Relat 25:889–922. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407508096700

Montoya RM, Kershaw C, Prosser JL (2018) A meta-analytic investigation of the relation between interpersonal attraction and enacted behavior. Psychol Bull 144:673–709. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000148

Newcomb TM (1956) The prediction of interpersonal attraction. Am Psychol 11:575–586. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0046141

Newcomb TM (1961) The acquaintanceship process. Holt, New York

*Nielsen S (2009) Why do top management teams look the way they do? A multilevel exploration of the antecedents of TMT heterogeneity. Strateg Org 7:277–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127009340496

Noon M (2010) The shackled runner: time to rethink positive discrimination? Work Employ Soc 24:728–739. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017010380648

O’Dea RE, Lagisz M, Jennions MD, Koricheva J, Noble DW, Parker TH, Nakagawa S (2021) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses in ecology and evolutionary biology: a PRISMA extension. Biol Rev 96:1695–1722. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12721

O’Reilly CA III, Caldwell DF, Chatman JA, Doerr B (2014) The promise and problems of organizational culture: CEO personality, culture, and firm performance. Group Org Manag 39:595–625. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601114550713

*Orpen C (1984) Attitude similarity, attraction, and decision-making in the employment interview. J Psychol 117:111–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1984.9923666

*Parent-Rocheleau X, Bentein K, Simard G (2020) Positive together? The effects of leader-follower (dis) similarity in psychological capital. J Bus Res 110:435–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.02.016

*Perry EL, Kulik CT, Zhou J (1999) A closer look at the effects of subordinate-supervisor age differences. J Org Behav 20:341–357. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1099-1379(199905)20:3%3c341::aid-job915%3e3.0.co;2-d

Persell CH, Cookson P (1985) Chartering and bartering: elite education and social reproduction. Soc Probl 33:114–129. https://doi.org/10.2307/800556

Pierce CA, Byrne D, Aguinis H (1996) Attraction in organizations: a model of workplace romance. J Org Behav 17:5–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199601)17:1%3c5::AID-JOB734%3e3.0.CO;2-E

Pugh M, Wahrman R (1983) Neutralizing sexism in mixed-sex groups: do women have to be better than men? Am J Soc 88:746–762. https://doi.org/10.1086/227731

Ridgeway CL (1991) The social construction of status value: gender and other nominal characteristics. Soc Forces 70:367–386. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/70.2.367

Ridgeway CL, Balkwell JW (1997) Group processes and the diffusion of status beliefs. Soc Psychol Q 60:14–31. https://doi.org/10.2307/2787009

Riordan CM (2000) Relational demography within groups: Past developments, contradictions, and new directions. In: Ferris GR (ed) Research in personnel and human resources management, vol 19. JAI Press, New York, pp 131–174

Rivera LA (2012) Hiring as cultural matching: the case of elite professional service firms. Am Soc Rev 77:999–1022. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122412463213

Rosenbaum ME (1986) The repulsion hypothesis. On the nondevelopment of relationships. J Pers Soc Psychol 51:1156–1166. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1156

*Rosenfeld HM, Jackson J (1965) Temporal mediation of the similarity-attraction hypothesis. J Pers 33:649–656. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1965.tb01410.x

*Roth PL, Thatcher JB, Bobko P, Matthews KD, Ellingson JE, Goldberg CB (2020) Political affiliation and employment screening decisions: the role of similarity and identification processes. J Appl Psychol 105:472–486. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000422

*Rupert J, Jehn KA, van Engen ML, de Reuver RS (2010) Commitment of cultural minorities in organizations: effects of leadership and pressure to conform. J Bus Psychol 25:25–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-009-9131-3

Sacco JM, Scheu CR, Ryan AM, Schmitt N (2003) An investigation of race and sex similarity effects in interviews: a multi-level approach to relational demography. J Appl Psychol 88:852–865. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.852

*Salminen M, Henttonen P, Ravaja N (2016) The role of personality in dyadic interaction: a psychophysiological study. Int J Psychophysiol 109:45–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2016.09.014

Schachter S (1959) The psychology of affiliation. Stanford University Press, Stanford

*Schieman S, McMullen T (2008) Relational demography in the workplace and health: an analysis of gender and the subordinate-superordinate role-set. J Health Soc Behav 49:286–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650804900304

Schneider B (1987) The people make the place. Pers Psychol 40:437–453. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1987.tb00609.x

Schneider B, Pulakos ED (2022) Expanding the I-O psychology mindset to organizational success. Ind Organ Psychol 15:385–402. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2022.27

Schneider B, Smith DB, Taylor S, Fleenor J (1998) Personality and organizations: a test of the homogeneity of personality hypothesis. J Appl Psychol 83:462–470. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.3.462

*Schreurs B, Druart C, Proost K, De Witte K (2009) Symbolic attributes and organizational attractiveness: the moderating effects of applicant personality. Int J Sel Assess 17:35–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2389.2009.00449.x

*Sears GJ, Holmvall CM (2010) The joint influence of supervisor and subordinate emotional intelligence on leader–member exchange. J Bus Psychol 25:593–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-009-9152-y

Singh R, Ho LJ, Tan HL, Bell PA (2007) Attitudes, personal evaluations, cognitive evaluation, and interpersonal attraction: on the direct, indirect, and reverse-causal effects. Br J Soc Psychol 46:19–42. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466606x104417

Singh R, Lin PKF, Tan HL, Ho LJ (2008) Evaluations, attitude similarity, and interpersonal attraction: testing the hypothesis of weighting interference across responses. Basic Appl Soc Psychol 30:241–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973530802375052

*Stark E, Poppler P (2009) Leadership, performance evaluations, and all the usual suspects. Pers Rev 38:320–338. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480910943368

Subramanian S, Billsberry J, Barrett M (2022) A bibliometric analysis of person-organization fit research: significant features and contemporary trends. Manag Rev Q. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-022-00290-9

Sunnafrank M (1992) On debunking the attitude similarity myth. Commun Monogr 59:164–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759209376259

Tatli A, Özbilgin MF (2012) An emic approach to intersectional study of diversity at work: a Bourdieuan framing. Int J Manag Rev 14:180–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00326.x

Terman LM (1938) Psychological factors in marital happiness. McGraw-Hill, New York

Tidwell ND, Eastwick PW, Finkel EJ (2013) Perceived, not actual, similarity predicts initial attraction in a live romantic context: evidence from the speed-dating paradigm. Pers Relat 20:199–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2012.01405.x

*Tsui AS, Porter LW, Egan TD (2002) When both similarities and dissimilarities matter: extending the concept of relational demography. Human Relat 55:899–929. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726702055008176

Turner BA, Chelladurai P (2005) Organizational and occupational commitment, intention to leave, and perceived performance of intercollegiate coaches. J Sport Manag 19:193–211. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.19.2.193

*Van Hoye G, Turban DB (2015) Applicant–employee fit in personality: testing predictions from similarity-attraction theory and trait activation theory. Int J Sel Assess 23:210–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12109

Verquer ML, Beehr TA, Wagner SH (2003) A meta-analysis of relations between person–organization fit and work attitudes. J Vocat Behav 63:473–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00036-2

Vogel RM, Rodell JB, Lynch JW (2016) Engaged and productive misfits: how job crafting and leisure activity mitigate the negative effects of value incongruence. Acad Manag J 59:1561–1584. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0850

Walster E, Aronson V, Abrahams D, Rottman L (1966) Importance of physical attractiveness in dating behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol 4:508–516. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0021188

Webster M Jr, Hysom SJ (1998) Creating status characteristics. Am Soc Rev. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657554

Wilkins AC (2012) Becoming black women: intimate stories and intersectional identities. Soc Psychol Q 75:173–196. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272512440106

*Xu J, Yun K, Yan F, Jang P, Kim J, Pang C (2019) A study on the effect of TMT characteristics and vertical dyad similarity on enterprise achievements. Sustain 11:1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102913

*Young IP, Place AW, Rinehart JS, Jury JC, Baits DF (1997) Teacher recruitment: a test of the similarity-attraction hypothesis for race and sex. Educ Adm Q 33:86–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X97033001005

Yu KYT, Verma K (2019) Investigating the role of goal orientation in job seekers’ experience of value congruence. Appl Psychol Int Rev 68:83–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12152

Zajonc RB (1968) Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. J Pers Soc Psychol Monogr 9:1–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0025848

*Zatzick CD, Elvira MM, Cohen LE (2003) When is more better? The effects of racial composition on voluntary turnover. Org Sci 14:483–496. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.14.5.483.16768

*Zhu DH, Chen G (2015) Narcissism, director selection, and risk-taking spending. Strateg Manag J 36:2075–2098. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2322

* Included in systematic review

Abbasi Z, Billsberry J, Todres M (2021) An integrative conceptual two-factor model of workplace value congruence and incongruence. Manag Res Rev. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-03-2021-0211

Adkins CL, Russell CJ, Werbel JD (1994) Judgments of fit in the selection process: the role of work value congruence. Pers Psychol 47:605–623. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1994.tb01740.x

Alliger GM, Janak EA, Streeter D, Byrne D, Turban D (1993) Psychological similarity effects in personnel selection decisions and work relations: A meta-analysis. In: Annual conference of the society for industrial and organizational psychology, San Francisco CA, USA.

*Allinson CW, Armstrong SJ, Hayes J (2001) The effects of cognitive style on leader-member exchange: a study of manager-subordinate dyads. J Occup Org Psychol 74:201–220. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317901167316

*Almeida S, Fernando M, Hannif Z, Dharmage SC (2015) Fitting the mould: the role of employer perceptions in immigrant recruitment decision-making. Int J Human Resour Manag 26:2811–2832. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.1003087

*Aronson ZH, Dominick PG, Wang M (2014) Exhibiting leadership and facilitation behaviors in NPD project-based work: does team personal style composition matter? Eng Manag J 26:25–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/10429247.2014.11432017

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editor, Professor Joern Block, and the anonymous reviewer for his or her valuable comments.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Consent to participate

The authors consent to participate.

Consent for publication

The authors consent for publication.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abbasi, Z., Billsberry, J. & Todres, M. Empirical studies of the “similarity leads to attraction” hypothesis in workplace interactions: a systematic review. Manag Rev Q 74, 661–709 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-022-00313-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-022-00313-5

Keywords

- Similarity-attraction hypothesis

- Attraction

- Value congruence

- Systematic review

- Recruitment

- Dissimilarity-repulsion hypothesis