Abstract

The paper presents a comprehensive review of research on de-internationalization, encompassing the themes of export withdrawal, subsidiary divestment, and backshoring or reshoring. A bibliometric technique (co-word analysis) on keywords from articles and book chapters published from 1980 to 2020 was initially used to confirm the main strands related to de-internationalization. Then, the study employed a bibliometric coupling analysis to identify the recent trends within each theme. The literature was divided into three clusters, which, using different but related terms, addressed the same phenomenon of firms’ decrease in foreign commitment. The ramifications of research on de-internationalization were examined for each of the clusters, mapping the issues deserving of further investigation and making recommendations for future research. The study uses an unprecedented method for understanding the de-internationalization phenomenon more broadly, delimiting its conceptual boundaries and mapping the different manifestations within a single theoretical domain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Although internationalization is typically described in the international business (IB) literature as a linear process (Johanson and Vahne 1977, 2009), it is often characterized by cyclical or irregular movements, in that a company's trajectory is impacted by opportunities or threats that “do not usually arrive in a continuous or controlled manner” (Welch and Luostarinen 1988, p. 42). The nonlinear nature of the phenomenon means that internationalization models do not take into account setbacks, interruptions or turnarounds (Fletcher 2001; Vissak 2010). Setbacks can result from back-shoring/re-shoring (relocating to the country of origin) or near-shoring (relocating to a nearby country) (e.g., Fratocchi et al. 2015; Merino et al. 2021; Moradlou et al. 2021), or from leaving specific countries or regions for other reasons (Sandberg et al. 2019). Interruptions can occur because the company reaches a limit where internationalization ceases (Nummela Vissak and Francioni 2020) for a period of time or permanently. Turnarounds can be movements of re-internationalization, with a return to countries from which the company had previously exited (e.g., Chen et al. 2019; Surdu and Ipsmiller 2021), or with a re-entry into international markets by a company that had become purely domestic after an initial period of internationalization. For Johanson and Kalinic (2016), periods of strong acceleration in internationalization are often followed by periods of deceleration. In any case, such movements confirm the nonlinearity of the internationalization process.

The concept of de-internationalization was first advanced by Welch and Luostarinen (1988), who posited that once a firm had internationalized, there was no guarantee that it would continue to develop international activities in the future. Scholars have studied de-internationalization and its manifestations under various labels such as de-internationalization, exit decision, foreign or international divestment, international market exit, export market withdrawal, reverse internationalization, backshoring, etc. These all refer to events of a similar nature in the firm’s international trajectory, whether it is looking at downsizing its foreign operations, switching its modes of operation, re-focusing on the domestic market, or bringing manufacturing back home. The problem is compounded by the large number of possibilities associated with each of these movements. For example, considering only divestment, closing a subsidiary does not necessarily mean a reduction in the degree of internationalization of a multinational enterprise (MNE), because the company may have opened other subsidiaries in other countries. In addition, a company may close a production subsidiary, but leave a commercial office or foreign distributors or representatives intact, which would also be considered an act of de-internationalization, but without exiting the foreign market. The transfer of a subsidiary from a distant country to a nearby country may have little impact in terms of the number of countries in which the MNE operates, but depending on the country or countries exited, it may also mean reducing the scope of internationalization from global (operating on several continents) to regional (operating on a single continent). Thus, there is a wide variety of de-internationalization movements, with very different impacts on the nature, scope, and intensity of the firm’s international activities (e.g., Tang et al. 2021; Trąpczyński 2016).

Even though scholars have been addressing this issue for at least thirty years, the focus on different types of decisions to de-internationalize may explain why the phenomenon is still under-researched, and why the results are often fragmented, ambiguous, and sometimes contradictory (Arte and Larimo 2019; Schmid and Mortschett 2020; Tan and Sousa 2015; Vissak 2010; Wan, Chen and Wu 2015). Other explanations reside on IB research’s focus on internationalization as a promising firm strategy, whereas de-internationalization has often been equated with failure (Kotabe and Ketkar 2009; Turcan 2011). However, efforts to de-internationalize may be the result of repositioning global operations (Benito and Welch 1997; Benito 2005), of correcting poorly made decisions, of discovering more attractive opportunities (Berry 2010; Boddewyn 1985), or of focusing on core competencies to enhance the firm’s long-term competitiveness (Fletcher 2001).

Therefore, the purpose of this review is to provide a comprehensive map of the literature on de-internationalization, using a bibliometric analysis of empirical articles published from January 1980 through December 2020, followed by a review of the research topics and recent theoretical perspectives adopted by the literature to help formulate new research questions that support the development of this research area. The objectives of this review are: (i) to reveal the structure of the literature on manifestations of de-internationalization through co-word analysis; (ii) to shed light on the field’s current areas of interest through bibliographic coupling analysis, which enables identification of clusters representing the latest research themes in the area of de-internationalization; and finally, (iii) from this bibliometric approach, to identify research and methodological issues that warrant attention, thereby offering insights into avenues for further research through a review of the articles included within each thematic cluster.

Previous reviews have examined the complexity of de-internationalization, either addressing it in its entirety (e.g., Tang et al. 2021; Trąpczyński 2016), or focusing on a specific form of it (e.g., Arte and Larimo 2019; Stentoft et al. 2016). Although previous reviews have identified gaps in the extant literature and have provided insights for future research, none of them have done so by applying a combination of bibliometric and content analysis techniques to a broader set of papers that encompass all the different manifestations of de-internationalization. By using bibliometric techniques, the present review unveils the different dimensions of the phenomenon under study, examining their commonalities and differences, and delimiting its theoretical boundaries. These are the paper’s main contributions. Hopefully, it will contribute to a broader understanding of the phenomenon, thus helping researchers to formulate new research questions and methodological procedures that will shape a more cohesive development of this emerging research area.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. First, we examine previous literature reviews of de-internationalization studies, followed by a conceptual discussion of the manifestations of the phenomenon in the extant literature. Next, we describe the method and the techniques we adopted. Then we present the results of the study (descriptive, co-occurrence and bibliometric analysis), followed by suggestions for future research. Finally, we present our concluding remarks, along with the study’s limitations and contributions.

2 Previous review studies of de-internationalization topics

Literature reviews are becoming ever more relevant as the pace of knowledge production accelerates. As new knowledge is added to the extant literature, a particular field becomes more fragmented and interdisciplinary, making it harder to assess the state-of-the-art (Snyder 2019). In the field of de-internationalization, previous reviews have examined various forms of setbacks, interruptions, and turnarounds (Table 1).

Some reviews have examined de-internationalization in several of its dimensions, although they have not examined its manifestations separately. Trąpczyński (2016) extended the concept of de-internationalization to include international market withdrawals, changes in operating modes, the allocation of value-adding activities, and international market withdrawals, as well as changes in the integration of sub-units of multinational firms. The author adopts a deductive approach, applying theory-driven dimensions of internationalization to previous research in order to identify the key developments and research gaps. More recently, Tang et al. (2021) synthesized theoretical arguments and empirical findings to map the concept of de-internationalization, its motives, barriers and long-term impacts on multiple stakeholders in a thematic framework. Lamba (2021) used a structured framework focusing on characteristics of a relevant set of articles to examine the extant literature. The most recent review (Kafouros et al. 2022) looked at studies on de-internationalization and re-internationalization, integrating the two phenomena into a conceptual framework that depicts a cycle starting with the initial internationalization process and advancing to de- and re-internationalization.

Other authors have dealt with specific manifestations of de-internationalization. Three reviews looked specifically at the phenomenon of manufacturing backshoring, reviewing the extant research to identify the most relevant factors for backshoring decision-making. They have categorized these factors into different clusters that influence the decision to backshore manufacturing (Stentoft et al. 2016), addressed who, what, where, when, why and how questions (Barbieri et al. 2018), and built a comprehensive backshoring framework that included domestic, international, and contingency factors driving offshoring and backshoring decisions (Boffeli and Johansson 2020).

Arte and Larimo (2019), on the other hand, focused on foreign divestment, exploring the shortcomings of the extant literature. They analyzed the main theories used to build divestment propositions and hypothesis, comparing their arguments and predictions. Coudonaris, Orero-Blat and Rodríguez-Garcia (2020) and Schmid and Morschett (2020) performed meta-analyses on subsidiary exit/divestment in order to synthesize the effects found in the original empirical articles. The formers’ study proposed a model of the antecedents influencing the parent firm’s and its subsidiaries’ financial performance, leading to subsidiary divestment. The latters’ study focused on the impact of 18 antecedents of subsidiary divestment related to the parent firm, the subsidiary itself, and the host country.

Summarizing, recent literature reviews of de-internationalization have looked at the phenomenon either covering only part of its manifestations, or using other methods (e.g., content analysis, thematic analysis, conceptual analysis, or meta-analysis), or including a smaller number of articles than the present review.

3 Manifestations of de-internationalization

De-internationalization has been conceptualized to include voluntary or involuntary decisions (Boddewyn 1983; Fletcher 2001), full or partial withdrawal (Benito and Welch 1997), defensive or offensive moves (McDermott 1996), and result of failure after international exposure (Sadikoglu 2018). Voluntary exits usually occur for financial or strategic reasons (Kotabe and Ketkar 2009), but they are always part of a decision made internally (Boddewyn 1983). In contrast, involuntary exits typically happen due to external reasons such as political or exchange risks, warfare, intellectual property rights issues, or even expropriation (Benito and Welch 1997; Kotabe and Ketkar 2009; Mandrinos et al. 2022). Although partial or full withdrawal are easy concepts to grasp, Benito and Welch (1997) theorize that the probability of a full exit from international operations declines as the internationalization process evolves; the same cannot be said about partial withdrawal, however, because companies often reduce some of their international operations over time as part of a bigger picture. As for defensive or offensive de-internationalization moves, McDermott (1996) defines the former as a result of a decline in competitiveness, loss of market share and deteriorating financial outcomes; the latter occurs when a profitable firm willingly chooses to divest some of its operations.

In the field of business, de-internationalization phenomena have been traditionally examined by strategic management and international management/business scholars (Benito and Welch 1997). They have used a variety of theoretical perspectives, including the resource-based view, the knowledge-based view, organizational learning theory, network theory, transaction cost theory, Dunning’s eclectic paradigm, internalization theory, institutional theory, and real options theory, among others (Tang et al. 2021). The choice of a theoretical perspective is usually related to the factors that are being investigated, whether internal or external to the firm. For example, from a resource-based view perspective, Sadikoglu (2018) claims that the two main reasons to de-internationalize are either a failure to transfer valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable resources to other markets, or an inability to transform those resources into meaningful offerings; Demirbag et al. (2011), on the other hand, use an institutional perspective to examine the impact of economic distance and economic freedom distance on subsidiary survival.

One common manifestation of de-internationalization is export withdrawal, either partial or complete. Nevertheless, research on export withdrawal has been the underdog in exporting research, with literature reviews seldom examining or even mentioning the subject (e.g., Chabowski et al. 2018; Paul et al. 2017). Scholars interested in exporting have looked at export withdrawal mainly as a negative outcome stemming from poor performance, often associated with the difficulty of overcoming export barriers. Bernini et al. (2016, p.1059) argue that many firms are, in fact, intermittent exporters, that is, they present “repeated, serial entry and exit to and from export markets.” Berg et al. (2022) differentiate between incidental exporters who become perennial exporters and those who exit foreign markets altogether, highlighting the role of labor productivity as a key factor.

Foreign subsidiary divestment has received substantial scholarly attention. IB research on foreign divestment can be traced back to Boddewyn’s (1983, 1985) work in the early 1980s. However, the subject was set aside until the 2000s (Tan and Sousa 2015). Arte and Larimo (2019) reviewed the theoretical frameworks and key empirical findings of research on foreign subsidiary divestment during the previous three decades. They concluded that the outcomes had sometimes been ambiguous, particularly in what concerned the impact of the institutional environment of the host country on divestment decisions. For the most part, research has focused on investigating factors associated with the exiting of foreign markets, including firm/subsidiary, industry, and country factors. However, Schmid and Morschett’s (2020) meta-analysis identified inconsistencies and non-significant results on divestment antecedents. Other studies examined the antecedents of subsidiary survival, since foreign subsidiaries that do not survive are those that have been divested. In fact, Kotabe and Ketkar (2009, p. 245) claimed that subsidiary exit and subsidiary survival are “two sides of the same coin”. Moreover, Thywissen (2015) claims that the divestment literature has focused on antecedents and outcomes but failed to examine process issues.

Another strand in this literature relates to backshoring. The concepts of outsourcing and offshoring have dominated the literature on global value chains for the past few decades. MNEs adopting these practices were driven by the desire to achieve efficiency and gain competitive advantages offered by low-cost economies (Capik 2017) through network collaboration and resource dependencies (Akyuz and Gursoy 2020). Recently, though, the question as to whether or not offshoring is the best choice for MNE operations has arisen, as attention to the phenomenon of backshoring has increased. McIvor and Bals (2021) present a conceptual framework for the backshoring decision, delineating the three stages involved in such decisions: drivers, exit analysis and reintegration/relocation analysis. Although reshoring is frequently used as a term to define any location change in manufacturing (Gray et al. 2013), some scholars have used it as a synonym for backshoring or back-reshoring (e.g., Ellram 2013), denoting the decision to relocate business processes, production, and services to the firm’s home country (Arlbjørn and Mikkelsen 2014), irrespective of the ownership mode chosen to operationalize it (Ancarani et al. 2015; Mlody 2016). Recent events such as the US-China trade dispute and Covid-19 pandemic have also been determinants of backshoring decisions, prompting research on the topic (e.g.: Chen et al. 2022).

Because de-internationalization has been conceptualized as part of a nonlinear process of internationalization, some scholars, particularly those studying small firm internationalization, born globals or international new ventures, have also examined re-internationalization. Re-internationalization usually takes place after the company has had a time-out period to adjust to certain conditions and to reevaluate its product offering or entry mode, after which it restarts its international operations (Welch and Welch 2009). Ali (2021) suggested that firms tend to perform better on re-internationalization attempts. A related phenomenon–the born-again global–was advanced by Bell et al. (2001) to describe firms that operated globally earlier, ceased their international activities for some reason for a significant period, and after a critical incident (e.g., acquiring new resources, accessing different networks or following a customer), made a quick return to foreign markets. Re-internationalization may also be the result of changes in the host country’s conditions. Whatever the process, the literature suggests that de- and re-internationalization are intertwined (Kafouros et al. 2022).

4 Method

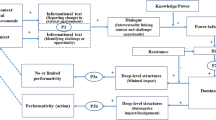

The study adopted a bibliometric approach to examine the literature on de-internationalization, followed by a literature review of the resulting clusters. Figure 1 presents a detailed workflow, including the research goals, data collection procedures and the analytical steps adopted in the study.

4.1 Data collection

The first step was to define the keywords to be used in the search, which was done by overviewing articles on de-internationalization and previous research and reviews. This initial search led to the identification and selection of different terms used to define processes and activities of de-internationalization: “de-international*”, “international/foreign exit strateg*”, “nternational/foreign divest*”, “international market exit”, “subsidiary survival/divest*/exit”, “international market withdraw*”, “backshor*” and “reshor*”. Although there are several sources for accessing data, the search used Scopus database because the simultaneous use of other databases might be considered unhelpful due to duplication of records (Harzing and Alakangas 2016). Furthermore, Scopus is one of the largest scholarly databases of peer-reviewed literature, and at the same time it is widely accepted as a database for bibliometric and big data analysis (Mongeon and Paul-Hus 2016; Donthu et al. 2021). Several authors of literature reviews have based their reviews on this database only, both in international business research (e.g., Barbieri et al. 2018; Lamba 2021) and other fields of business and management (e.g., Lim et al. 2021; Yadav et al. 2022).

Articles and book chapters published in English from January 1980 through December 2020 were extracted in order to ensure the biggest coverage of items possible. However, we did not include conference papers and other non-peer-reviewed material, with the exception of book chapters. This procedure has been encouraged by some scholars (e.g., Adams et al. 2017), who claim that book chapters present the highest level of credibility within the so-called grey literature. Apart from the keywords related to the backshoring phenomenon, the scope was limited to the fields of Business, Management and Accounting, which share a similar approach to the phenomenon under scrutiny. This first round yielded a total of 450 papers (including duplicates due to the various searches performed separately). The results were then compiled and duplications were eliminated. The next step was a thorough examination of abstracts and keywords in order to exclude out-of-scope papers, that is, articles about divestment in general, not focused on international or foreign divestment. The final database consisted of 234 items (221 articles featured in peer-reviewed journals and 13 book chapters), published from 1980 through 2020. The data collection process is also depicted in Fig. 1.

4.2 Analysis techniques and tools

A bibliometric analysis is useful for rigorously mapping the cumulative scientific knowledge of an establishing research area (Dunthu et al. 2021). The method consists of a quantitative analysis of empirical data extracted from the literature and is commonly used to map scientific fields (Zupic and Čater 2015), especially emerging ones (Rialti et al. 2019). It provides visual representation of the relationships that can be established by publications, authors, journals, or keywords as they are positioned in a structure called the “bibliometric network” (Van Eck and Waltman 2014). This study followed the protocol proposed by Zupic and Čater (2015).

Step 1. A descriptive analysis was performed for the purpose of portraying the evolution of the field over the past few decades and the main journals that have published works related to de-internationalization. The co-word analysis technique was applied to uncover the cognitive structure of the field and to assess if the papers selected were related and addressed aspects of the same phenomenon. The technique, based on the frequency of co-occurrence of keywords in the articles (Whittaker 1989), was developed to provide a content picture of research topics most present in a field/research area and how they relate with each other. This is achieved by measuring the strength of the keywords’ co-occurrence links, thus revealing a network (Su and Lee 2010). The keywords used in the analysis may be either supplied by the author or extracted from the title and abstract of a publication (Van Eck and Waltman 2014). Thus, the decision was not to exclude the 38 articles without an original set of keywords, but to extract the keywords from their titles and abstracts. Additionally, some of the keywords had to be standardized (Su and Lee 2010). For instance, “de-internationalisation” was replaced with “de-internationalization,” and the different terms used to designate a multinational enterprise were replaced with “MNE.” Although “foreign divestment,” “international divestment,” “foreign divestiture” and “international divestiture” are sometimes used interchangeably, they were all kept in their original form.

Step 2. The works published in the last 6 years (2015–2020) were organized into the three main themes found in the previous analysis (keyword co-occurrence) and submitted to a BC technique. This technique assumes that articles that have more references in common have a higher probability of addressing common themes (Kessler 1963), and is best used within a specific timeframe (Zupic and Čater 2015). Additionally, when used in a database containing only the most recent articles, it can be useful to determine novel and upcoming theoretical trends in the field, as can be seen in Steinhäuser, Paula, and Macedo-Soares (2020). Because the goal was to analyze the structure of emerging articles, the BC technique was preferred over co-citation analysis, due to its staticity over time (Zupic and Čater 2015). The analysis used the VOSViewer Application, which provides graphical bibliometric maps and networks made of nodes and edges, indicating relationships between pairs of nodes. The most closely related nodes were divided into clusters (Van Eck and Waltman 2014).

Step 3. Once the thematic clusters were identified, all articles included in each cluster were read to identify their most important contributions, as well as the main research methods and variables analyzed. This targeted literature review provided valuable information about the field’s key dimensions, helping to identify research gaps and possible future avenues (Clark et al. 2021).

5 Descriptive results

Despite first appearing in the 1980s, research on de-internationalization took a long time to become established. It was not until the late 2000s that the number of papers started to increase (Fig. 2).

Table 2 presents the top journals with the largest number of articles. They account for almost 50% of the total 221 peer-reviewed articles published between 1980 and 2020. The International Business Review published 9.5% of all the papers, followed by the Journal of International Business Studies and Journal of World Business with 5.9% each. Although most journals are related to IB, there is also a significant number of Supply Management, Operations Management and Strategic Management journals.

6 Keyword co-occurrence analysis

The co-word analysis using articles’ keywords as nodes produced three clusters. Table 3 presents the clusters with the frequency of the keywords (occurrence) and the total strength of the links of an item with other items (total link strength). The keywords that were originally used to search the database are highlighted in the table with an asterisk (*): de-internationalization and international divestment (cluster 1); subsidiary survival, subsidiary divestment and foreign divestment (cluster 2); and reshoring and backshoring (cluster 3).

The graphical representation of the network retrieved from VOSViewer (Fig. 3) shows that, despite the division of subjects, there are also connections among them. Both requirements for establishing a network structure – network actors (keywords) and network ties (links between them) – were met (Su and Lee 2010). Therefore, one can infer that at least part of the knowledge structure of the de-internationalization literature was disclosed.

The clusters formed by keywords provide interesting insights. The first (green) cluster—De-internationalization and Re-internationalization – shows that research on de-internationalization and research on re-internationalization are indeed connected. Research has examined what firms do differently once they re-internationalize in order to determine what they have learned. De-internationalization has also been studied by researchers of retailing (e.g., Alexander et al. 2005), since retailers underwent a nonlinear process of internationalization during the 1980s and 1990s, with divestment activities ranging from store closures to chain sales and market exits (Alexander et al. 2005). Case studies have been the primary method adopted by research on de-internationalization processes (Kotabe and Ketkar 2009; Huang et al. 2019), perhaps because of the difficulty of obtaining data on de-internationalization, which often are not disclosed by firms. Lastly, research on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) has emphasized how they follow different stages of internationalization, which are often non-incremental and nonlinear (Dominguez and Mayrhofer 2017; Vissak and Francioni 2013).

The second cluster (red) – Foreign Subsidiary Divestment and Survival – focuses on MNEs, which makes sense, considering that the keywords are related to subsidiaries’ divestment or survival, choice of entry and exit mode, performance, uncertainty, and real options. These issues are usually investigated in the context of larger, resource-rich firms that have more options than export withdrawal. Research on foreign subsidiary divestment is highly connected with performance outcomes (Sousa and Tan 2015), subsidiary survival (Kotabe and Ketkar 2009), and real options theory (Chung et al. 2013). Research has focused mainly on investigating factors associated with the exiting of foreign markets, including firm, subsidiary, industry, and country factors. Although poor performance seems to be the most prominent motive, several other antecedents have been examined, such as productivity (Engel et al. 2013), strategic choices (Ozkan 2020), previous international experience (Sousa and Tan 2015), resources and innovative capabilities (Konara and Ganotakis 2020), and alliances and networks (Iurkov and Benito 2020). A related set of studies examines the antecedents of subsidiary survival. Most of these studies agree that survival does not depend entirely on performance and profitability, but on other factors also, including entry and equity modes (Hong 2015), institutional, cultural, and cross-national distance (Cassio-de-Souza and Ogasavara 2018), previous international experience (Yang et al. 2015), host country characteristics (Wang and Larimo 2020), and home country context (Peng and Beamish 2019).

The third cluster (blue) – Backshoring – includes the terms backshoring, reshoring and back-reshoring, often used interchangeably (Ellram 2013). This decision does not necessarily mean that the firm will start manufacturing on its own, because the outsourcing option is still on the table, provided that the factories are in its home country. The term "nearshoring" does not appear as part of this cluster because nearshoring typically refers to bringing manufacturing activities to a different country, one that is closer to the home country (Hartman et al. 2017). Therefore, it is not part of a de-internationalization process. Some studies indicate that backshoring is not unique to MNEs (Stentoft et al. 2016); medium-sized firms may wish even more keenly to backshore (Arlbjørn and Mikkelsen 2014). MNEs’ and SMEs’ backshoring processes differ in terms of motivation, with large companies showing more concern about being responsive and maintaining production close to R&D, and smaller ones being motivated by product quality and supply reliability (Arlbjørn and Mikkelsen 2014; Gray et al. 2013). Stentoft et al. (2016) suggest that industry-related contingencies could be relevant. However, one study showed that firms operating in both high-tech and labor-intensive industries have repatriated their operations (Ancarani and Di Mauro 2018).

7 Bibliometric coupling and content analysis

The BC technique was used to examine the papers from 2015 through 2020 divided beforehand into thematic clusters using co-word analysis. This analysis enabled us to tell which of the papers were related to the others because they cited similar sources, and to qualitatively identify research trends through a content analysis.

7.1 De-internationalization and Re-internationalization

Twenty-two published articles were grouped into three clusters according to the strength of their connections (Fig. 4).

The first (green) cluster comprises nine articles and is labeled Born Globals down the Road due to the number of articles on de-internationalization of early exporters or born-global firms (e.g., Huang et al. 2019). These articles examine what happened to firms that, despite a very promising beginning to their internationalization, retracted their operations along the way. These studies typically use a longitudinal approach (e.g., Vissak et al. 2020), and look at export behavior as an accessible entry mode for smaller and younger firms (Dominguez and Mayrhofer 2017). Three studies (Dominguez and Mayrhofer 2017; Vissak and Zhang 2016; Vissak et al. 2020) investigate internal and external factors influencing firms’ nonlinear internationalization processes, including lack of knowledge, lack of network relationships, effectual behavior, home and host country constraints, and global competitiveness.

The second (red) cluster includes 10 articles and is labeled Export Discontinuation Patterns, since most of the papers focus on patterns of discontinuing export activities by smaller firms (e.g., Choquette 2019; Deng et al. 2017). Other than insufficient sales performance, export withdrawal seems to occur more often with experienced firms, those with a larger number of assets distributed internationally, and those exiting other markets simultaneously (Chen et al. 2019). Under turbulent conditions, market-oriented firms are more likely to exit, whereas having relational capital in a foreign market may decrease the chance of exiting (Yayla et al. 2018). Prior market experience in developed markets can influence the continuation of exporting even to emerging markets (Sandberg et al. 2019). These authors also suggest that SMEs could compensate for their lack of experience by being larger, more competitive and by developing innovation capabilities. Exploring the impact of experience on exiting export markets, Choquette (2019) distinguishes between the effects of import and export-driven experience: while previous export experience may decrease the likelihood of exiting, import-based market experience may increase it. As for the influence of speed of internationalization on the likelihood of exiting export markets, Yayla et al. (2018) found no empirical support for this proposition, whereas other studies suggest that young ventures that rapidly enter export markets have a hard time sustaining their international performance unless they face a highly competitive environment from the beginning, or unless they resort to foreign ownership arrangements that can help them reduce the “triple liability of rapidness, newness and foreignness” (Deng et al. 2017, p. 269).

The third (blue) cluster, Re-internationalization, comprises only three papers with authors in common, although papers on this issue also appear in the other two clusters. Surdu et al. (2018) examine the antecedents of market re-entry to determine their influence on the timespan between exiting and re-entering, and to investigate what would lead the firm to make a second attempt. They propose that the depth of experience acquired in operating in a specific market may increase uncertainty and delay re-entry, but this effect could be reduced by the institutional quality of the host market. In another paper, Surdu et al. (2019) investigate entry mode changes by companies while re-entering, arguing that unsatisfactory performance influences the learning process for re-entrants, and consequently the level of commitment. Corroborating previous findings, Surdu and Narula (2020) posit that accumulated market-specific knowledge may slow down re-internationalization. They suggest that the ability to transform negative experiences into firm-specific advantages depends on how quickly the organization makes the next attempt, irrespective of how long it had been active in that market previously, or whether it comes from a developed or emerging country. The three articles offer insights into the role of experiential learning, including how organizations process and use the knowledge accumulated in their international experiences.

7.2 Foreign subsidiary divestment and survival

The BC technique was applied to 42 foreign subsidiary divestment and subsidiary survival articles published between 2015 and 2020 (Fig. 5).

The first (red) cluster (22 articles)–Subsidiary Survival–looks at antecedents of subsidiary survival and is mostly related to subsidiary characteristics such as changes in core activities (Kim 2017), expatriate staffing level (Peng and Beamish 2019), and equity ownership arrangements (Hong 2015), but also host country characteristics, including geographical and cross-national distance (Cassio-de-Souza and Ogasavara 2018), and institutional development (Getachew and Beamish 2017). Papers analyzing the effect of firms’ previous international experience show somewhat ambiguous results. While Cassio-de-Souza and Ogasavara (2018) find that local experience has a positive moderating impact on the survival of cross-nationally distant subsidiaries, Wang and Larimo (2017, p. 176) point out that the “relationship of ownership strategy and subsidiary survival in foreign acquisitions is contingent upon cultural distance and host country development but not on firm experience”. Yang et al. (2015) argue that MNEs that learn from the failure of prior entrants show lower exit rates. Inconsistent findings are also pointed out in Arte and Larimo’s (2019) literature review and Schmid and Morschett’s (2020) meta-analysis, which shows the persistence of this subject and the need for further investigation to reach more robust conclusions.

The second (green) cluster, Divestment Strategies, includes 20 papers. These papers also acknowledge the role of previous experience in explaining foreign divestment (e.g., Tan and Sousa 2015) and home and host country-related antecedents (e.g., Burt et al. 2019), but from a divestment or exit perspective. The most noticeable difference from the previous cluster is the lack of papers focusing on subsidiary characteristics. Instead, the research in this cluster focuses on strategic choices made by MNEs in relation to their domestic and international investments. Sousa and Tan (2015), for instance, investigate the relevance of strategic fit between a headquarters and its foreign affiliates in determining which one gets divested, and later on the same authors investigate whether or not business relatedness impacts the exit decision (Tan and Sousa 2018). Ozkan (2020) focuses on the misalignment between firms’ strategies and foreign market risk. Procher and Engel (2018, p. 529) look at “segmented intersubsidiary competition,” concluding that foreign investments compete among themselves for divestment decisions. There are also papers dealing with retail divestment issues (e.g., Burt et al. 2019).

7.3 Backshoring

Finally, the BC technique was applied to 56 backshoring articles published from 2015 through 2020, and two clusters emerged (Fig. 6). Both clusters include studies on motivations and determinants of backshoring activities, but with other aspects differentiating them.

The first (red) cluster, Backshoring Outcomes, includes 29 papers. Stentoft et al. (2016) identified seven groups of antecedents of a backshoring decision: cost, quality, time and flexibility, access to skills and knowledge, risk, market, and other factors. Fratocchi et al. (2016) developed an integrative framework for backshoring motivations, considering their purpose (customer perceived value versus cost efficiency) and level of analysis (firm-specific versus country-specific). Brandon-Jones et al. (2017) indicate that the benefits of backshoring tend to outweigh the costs because the decision tends to generate positive abnormal stock returns. Other studies highlight the gains in knowledge retention (Nujen et al. 2019), manufacturing or innovative capabilities (Nujen and Halse 2017), product quality or the quality of the production infrastructure in the host country, and responsiveness (Moradlou et al. 2017). Backshoring also appears to have a positive effect on changing business models and on brand repositioning (Robinson and Hsieh 2016) related to “consumer reshoring sentiment,” a construct that measures consumer attitudes toward companies that backshore, from the “made-in effect” and “quality superiority” to “ethical issues in host countries” (Grappi et al. 2018, p. 196), translating into consumer willingness to reward these firms (Grappi et al. 2015, 2018).

The second (green) cluster comprises 23 articles that are generally more recent than those in the previous cluster. Its most prominent theme was used to label the cluster Changes in Home Country Context. Articles in this cluster discuss how innovation and technological changes in production processes can impact a firm’s decision to reshore (e.g., Lampón and González-Benito 2019; Martínez-Mora and Merino 2020). Dachs et al. (2019) find a positive link between backshoring and investments in industry 4.0 technologies, and Lampón and González-Benito (2019) conclude that backshoring results in an upgrading in manufacturing compared to the time of offshoring. However, Ancarani, Di Mauro and Mascali (2019) suggest that European companies that backshored did so without resorting to labor-saving technologies. Thus, the adoption of new technologies might be more important to some businesses than to others, depending on their strategic goals. For Halse, Nujen and Solli-Saether (2019), automation is more of a means for achieving the goal of backshoring than a reason in itself. As for the institutional changes in the home country, Ciabuschi et al. (2019) indicate that home country risk should be part of backshoring considerations, while Moradlou et al. (2021) focus on changes to the demand pattern in the home country. Other authors emphasize the relevance of production and professional networks in the home country for the decision to bring some activities back home (Baraldi et al. 2018; Halse et al. 2019).

8 Future directions for research

This review is based on the articles included in each thematic cluster derived from the BC analysis, and it addresses the third objective of the research, which is to identify research and methodological issues that warrant attention, thereby offering insights into avenues for further research. Studies on de-internationalization cover a variety of research themes, with most of them meriting further investigation. There are opportunities for studies covering different aspects of partial de-internationalization, such as export market withdrawal, subsidiary divestment, or backshoring, as well as complete de-internationalization. Variables affecting the decision can be at the firm and subsidiary level, industry level, or home/host country level. Table 4 maps the main issues deserving additional research extracted from this bibliometric review, discussed in detail below. Table 5 presents selected research issues and the studies supporting them. These suggestions come from gaps identified in the literature by other authors as well as from those that we believe deserve more scholarly attention.

8.1 Methodological aspects

Longitudinal and cross-sectional approaches may both contribute to extending the present knowledge on de-internationalization. Longitudinal studies aim at understanding changes that are internal or external to the firm, and that prompt the de-internationalization decision. As for cross-sectional studies, these may focus on firms in general or they may compare specific groups of firms, such as born globals with late internationalizers, successful exporters with others that exited under similar conditions, emerging country multinationals with developed country multinationals, or firms that backshored insourcing, outsourcing, or both. Longitudinal studies are particularly useful for comparing initial conditions at the time of international market entry with those at the time that the firm partially or completely ceases it international activities. Typically, these studies use panel data from secondary sources, but data can also come from selected case studies to get a more in-depth understanding of the research issue. One problem with longitudinal studies is that researchers typically must rely on secondary sources, which do not provide all the varieties of data needed to test the many hypotheses found in the literature. Thus, key research gaps are identified, but not addressed due to lack of empirical data. When they are addressed using case studies, they can provide analytical generalizations, which may help with understanding the mechanisms behind de-internationalization, but not their incidence. Cross-sectional studies have the advantage of more flexibility in data collection, due to the possibility of using surveys, in addition to secondary data. Nevertheless, retrospective data collected by surveys often fail to capture the genuine antecedents of the phenomena of interest.

8.2 Firm- and subsidiary-related variables

The impact of a firm’s international experience on de-internationalization remains unclear. Authors have studied the role played by international experience and market knowledge in different aspects of de-internationalization, particularly those related to subsidiary divestment and export market withdrawal (e.g., Choquette 2019), but also in studies concerning re-internationalization (e.g., Surdu et al. 2018). In their meta-analysis of the antecedents of foreign subsidiary divestment, Schmid and Morschett (2020) found mixed results, depending on the different operationalizations, as well as the type of experience (general or market-specific). Their findings show a positive and significant result only for market-specific experience. However, in their meta-analysis all the studies used secondary data, which do not provide fine-grained data for analyzing distinct aspects of international experience, a multi-faceted construct. Scholars need to map the conceptual domain of the construct in order to disentangle its various potential impacts on different forms of de-internationalization. In addition, experience, learning, and accumulated knowledge are also different, although related, constructs. There is no guarantee that a firm is capable of absorbing and accumulating knowledge potentially gained during the period it operated in a given market.

The role of networks in preventing or accelerating de-internationalization seems reasonably clear, but studies have not examined different types of networks, the nature of relationships with local partners, types of bonds, and for how long these relationships have lasted. In general, it seems that the lack of relational capital accelerates export market withdrawal and vice-versa. This issue, however, does not seem relevant in other manifestations of de-internationalization. Managerial perceptions also need to be further investigated, including prior expectations of subsidiary performance, perceived alignment of the strategies adopted by the firm with its original goals, and its relationship with performance outcomes. Firm innovativeness and time in the foreign market should also be examined in more depth, particularly in the case of born globals.

8.3 Industry-level variables

Industry-level variables have received almost no attention in de-internationalization research, as noted by Arte and Larimo (2019), even though studies have often examined firms from different industries. The exceptions are studies of backshoring that have considered technological aspects of the industry as an antecedent of these decisions. In fact, industry type should be at least a moderating variable in studies that examine a range of industries. In addition, because firms imitate others in their industry, particularly leading firms, an issue to be investigated is isomorphic behavior. If a flagship firm decides to backshore, its actions may signal to others a new strategic direction in terms of re-locating production or assembly facilities in the home country.

8.4 Country-level variables

The impact of host country variables on several types of de-internationalization has been amazingly difficult to grasp (Schmid and Morschett 2020). Most research has focused on cultural distance (e.g., Sousa and Tan 2015; Vissak and Francioni 2013) and country risk variables, with conflicting or non-significant results. These studies have used mostly available indexes of country risk and cultural distance to measure the constructs, but the type of operational measures used has led to nonsignificant results (Schmid and Morschett’s 2020). What appears to be relevant is how managers perceive risk and cultural distance at the time of entry and at the time of the decision to exit. Indeed, there is no assurance that managerial perceptions are consistent with indexes made available by supranational organizations and other sources, reliable as they may be. Also, depending on the location of the parent company, perceptions of risk may vary substantially. Thus, there is a need to abandon old (and easy) ways of measuring country risk and cultural distance and to develop more consistent measures of managerial perceptions of these constructs. This is even more difficult if scholars intend to measure perceptions at the time of entry and time of exit. Managerial perceptions do change with experience and time in the market, perhaps substantially. Also, only a few researchers have considered host country institutional factors and institutional distance as antecedents of de-internationalization (e.g., Gaur et al. 2019). Institutional variables may provide more interesting results, because they grasp more specific aspects of the firm’s operating environment than cultural distance and country risk. Disruptive events such as financial crises, natural disasters, or health crises may force a firm to undergo partial or full de-internationalization, although firms may re-internationalize later. Additionally, if a firm decides to leave all foreign markets and ceases international activities altogether, host market conditions are probably not relevant, unless the firm operates in a single foreign market or in a set of foreign markets under similar political and economic conditions. Instead, firm, industry and home country conditions may have played a much more important role in such decision.

Scholars have largely ignored home country factors related to de-internationalization, possibly because most studies have focused on firms from one specific home country, particularly Japan and South Korea (Arte and Larimo 2019). Even so, home country factors may be particularly meaningful in explaining de-internationalization of emerging market multinationals. Because these firms originate in countries with weak institutional environments, changes in home country environment, particularly in macroeconomic and political conditions and government support, may impact de-internationalization. From a different perspective, backshoring studies have examined home country issues, specifically changes in technology and improvement in home country manufacturing conditions that facilitate the re-establishment of production facilities in the home country (e.g., Lampón and González-Benito 2019). This is a promising line of inquiry, particularly given recent geopolitical changes (Kafouros et al. 2022), and technology advances allowing them to be implemented. In addition, several scholars have pointed out a need to investigate as to whether or not technological changes in production processes are necessary or if they simply enable conditions for backshoring (e.g., Ancarini and Di Mauro 2018; Dachs et al. 2019; Martínez-Mora and Merino 2020).

9 Final considerations

This review contributes to the extant literature by (a) applying bibliometric and content analyses techniques to (b) a broader range of papers than previous reviews, (c) covering all the different manifestations of de-internationalization. By doing so, we were able to uncover the conceptual domain of de-internationalization, a phenomenon that has received growing attention in the field of IB, recognizing its different, although related, strands. Due to the fragmented nature of this literature, some of these research traditions do not talk with each other but evolve in a parallel way. A broader view of the literature on de-internationalization may thus help to identify commonalities that are built on diverse, yet related, contributions. Because of the different strands and theoretical perspectives in the bulk of research examined in this paper, scholars should be particularly aware of differences in construct operationalizations, since previous studies often used differing proxies for the same construct, thus making the comparison of results and the accumulation of knowledge difficult. Multidisciplinary and metatheoretical perspectives have the potential to provide meaningful advances for future research. The study also contributes by offering a broad view of the issues that have been recently addressed, allowing the suggestion of future research directions to be pursued by scholars interested in investigating de-internationalization. These are timely contributions, in light of the new wave of de-internationalization associated with recent geopolitical realignments and disruptions in global supply chains due to the pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

One limitation of the present study was the use of only one database (Scopus) to conduct the extraction of data, meaning that a few related articles may have been left out. Even so, the Scopus database yielded more results than its counterparts such as the WoS database, and there is a significant number of articles in the final database, thus enabling the research to fulfill its goals. Moreover, other relevant literature reviews have also used only the Scopus database (e.g., Barbieri et al. 2018; Lamba 2021; Lim et al. 2021; Yadav et al. 2022). In addition, other limitations derive from the bibliometric techniques used. Although it may help to reduce the subjectivity in literature reviews, it requires the intervention of the researchers to define the searching of key-words, select the most relevant work and complement the results with their outputs and thoughts. Furthermore, although some bibliometric techniques have been applied to smaller data subsets in articles with different purposes (e.g.: Sánchez-Pérez et al. 2021; Steinhäuser et al. 2021), they are usually more suitable for large datasets (Donthu et al. 2021). Finally, our review only covered the areas of Business, Management and Accounting. Other fields such as History, Economic Geography, Economics, and Political Science examine the phenomenon using different lenses and could therefore provide interesting new insights for the extant research.

Despite these limitations, we believe the study contributes to the IB research by providing a more comprehensive approach to de-internationalization. In unifying a somewhat scattered research field and establishing the connections between the different strands, we hope we have shown that it is a multidisciplinary phenomenon that can be examined from different levels and perspectives. The study also contributes by examining the most recurring themes and providing possible avenues for future research.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Adams RJ, Smart P, Huff AS (2017) Shades of gray: guidelines for working with the grey literature in systematic reviews for management and organizational studies. Int J Manag Rev 19(4):432–454

Akyuz GA, Gursoy G (2020) Strategic management perspectives on supply chain. Manage Rev Quarter 70:213–241

Alexander N, Quinn B, Cairns P (2005) International retail divestment activity. Int J Retail & Distribution Manage 33(1):5–22

Ali S (2021) Do firms perform better during re-internationalisation? Int J Business Global 27(4):492–504

Ancarani A, Di Mauro C (2018) Reshoring and Industry 4.0: how often do they go together? IEEE Eng Manage Rev 46(2):87–96

Ancarani A, Di Mauro C, Fratocchi L, Orzes G, Sartor M (2015) Prior to reshoring: A duration analysis of foreign manufacturing ventures. Int J Prod Econ 169:141–155

Ancarani A, Di Mauro C, Mascali F (2019) Backshoring strategy and the adoption of Industry 4.0: evidence from Europe. J World Business 54(4):360–371

Arlbjørn JS, Mikkelsen OS (2014) Backshoring manufacturing: notes on an important but under-researched theme. J Purch Supply Manag 20(1):60–62

Arte P, Larimo J (2019) Taking stock of foreign divestment: Insights and recommendations from three decades of contemporary literature. Int Bus Rev 28(6):101599

Baraldi E, Ciabuschi F, Lindahl O, Fratocchi L (2018) A network perspective on the reshoring process: the relevance of the home-and the host-country contexts. Ind Mark Manage 70:156–166

Barbieri P, Ciabuschi F, Fratocchi L, Vignoli M (2018) What do we know about manufacturing reshoring? J Global Oper Strateg Sourcing 11(1):79–122

Bell J, McNaughton R, Young S (2001) ‘Born-again global’ firms: An extension to the ‘born global’ phenomenon. J Int Manag 7(3):173–189

Benito GR (2005) Divestment and international business strategy. J Economic Geograph 5(2):235–251

Benito GR (2015) Why and how motives (still) matter. Multinatl Bus Rev 23(1):15–24

Benito GRG, Welch LS (1997) De-Internationalization. Manag Int Rev 37:7–25

Benstead AV, Stevenson M, Hendry LC (2017) Why and how do firms reshore? A contingency-based conceptual framework. Oper Manag Res 10(3):85–103

Bernini M, Du J, Love JH (2016) Explaining intermittent exporting: exit and conditional re-entry in export markets. J Int Bus Stud 47(9):1058–1076

Berrill J, Hovey M (2018) An empirical investigation into the internationalisation patterns of UK firms. Transnational Corporations Rev 10(4):396–408

Berry H (2010) Why do firms divest? Organ Sci 21(2):380–396

Bettiol M, Chiarvesio M, Di Maria E, Di Stefano C, Fratocchi L (2019) What happens after offshoring? A comprehensive framework. In: International business in a VUCA world: The changing role of states and firms. Emerald Publishing Limited

Boddewyn JJ (1983) Foreign and domestic divestment and investment decisions: like or unlike? J Int Bus Stud 14(3):23–35

Boddewyn JJ (1985) Theories of foreign direct investment and divestment: a classificatory note. Manag Int Rev 25(1):57–65

Boffelli A, Johansson M (2020) What do we want to know about reshoring? Towards a comprehensive framework based on a meta-synthesis. Oper Manag Res 13(1):53–69

Brandon-Jones E, Dutordoir M, Neto JQF, Squire B (2017) The impact of reshoring decisions on shareholder wealth. J Oper Manag 49:31–36

Burt S, Coe NM, Davies K (2019) A tactical retreat? Conceptualising the dynamics of European grocery retail divestment from East Asia. Int Bus Rev 28(1):177–189

Capik P (2017) Backshoring: towards international business and economic geography research Agenda. Iin breaking up the global value chain (advances in international management, Vol. 30), Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp. 141–155

Cassio-de-Souza F, Ogasavara MH (2018) The impact of cross-national distance on survival of foreign subsidiaries. Brazilian Business Review 15(3):284–301

Castellões B, Dib LA (2019) Bridging the gap between internationalisation theories and de-internationalisation: a review and research framework. Int J Bus Globalisation 23(1):26–46

Chabowski B, Kekec P, Morgan NA, Hult GTM, Walkowiak T, Runnalls B (2018) An assessment of the exporting literature: Using theory and data to identify future research directions. J Int Mark 26(1):118–143

Chen J, Sousa CM, He X (2019) Export market re-entry: Time-out period and price/quality dynamisms. J World Bus 54(2):154–168

Chen H, Hsu C-W, Shih Y-Y & Caskey D (2022) The reshoring decision under uncertainty in the post-COVID-19 era. J Business & Indust Marketing Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print.

Choquette E (2019) Import-based market experience and firms’ exit from export markets. J Int Bus Stud 50(3):423–449

Chung CC, Lee SH, Lee JY (2013) Dual-option subsidiaries and exit decisions during times of economic crisis. Manag Int Rev 53(4):555–577

Ciabuschi F, Lindahl O, Barbieri P, Fratocchi L (2019) Manufacturing reshoring: a strategy to manage risk and commitment in the logic of the internationalization process model. Eur Bus Rev 31(1):139–159

Clark WR, Clark LA, Raffo DM, Williams RI Jr (2021) Extending Fisch and Block’s (2018) tips for a systematic review in management and business literature. Management Review Quarterly 71:215–231

Coudounaris DN, Orero-Blat M, Rodríguez-García M (2020) Three decades of subsidiary exits: Parent firm financial performance and moderators. J Bus Res 110:408–422

Dachs B, Kinkel S, Jäger A (2019) Bringing it all back home? Backshoring of manufacturing activities and the adoption of Industry 40 technologies. J World Business 54(6):101017

Demirbag M, Apaydin M, Tatoglu E (2011) Survival of Japanese subsidiaries in the middle east and North Africa. J World Bus 46(4):411–425

Deng Z, Jean RJB, Sinkovics RR (2017) Polarizing effects of early exporting on exit. Manag Int Rev 57(2):243–275

Dominguez N, Mayrhofer U (2017) Internationalization stages of traditional SMEs: increasing, decreasing and re-increasing commitment to foreign markets. Int Bus Rev 26(6):1051–1063

Donthu N, Kumar S, Mukherjee D, Pandey N, Lim WM (2021) How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: an overview and guidelines. J Bus Res 133:285–296

Ellram LM (2013) Offshoring, reshoring and the manufacturing location decision. J Supply Chain Manag 49(2):3

Engel D, Procher V, Schmidt CM (2013) Does firm heterogeneity affect foreign market entry and exit symmetrically? Empirical evidence for French firms. J Econ Behav Organ 85:35–47

Fletcher R (2001) A holistic approach to internationalisation. Int Bus Rev 10(1):25–49

Fratocchi L, Ancarani A, Barbieri P, Di Mauro C, Nassimbeni G, Sartor M, Zanoni A (2015) Manufacturing back-reshoring as a nonlinear internationalization process. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, In The future of global organizing

Fratocchi L, Ancarani A, Barbieri P, Di Mauro C, Nassimbeni G, Sartor M, Zanoni A (2016) Motivations of manufacturing reshoring: an interpretative framework. Int J Phys Distrib Logist Manag 46(2):98–127

Gaur AS, Pattnaik C, Singh D, Lee JY (2019) Internalization advantage and subsidiary performance: the role of business group affiliation and host country characteristics. J Int Bus Stud 50(8):1253–1282

Getachew YS, Beamish PW (2017) Foreign subsidiary exit from Africa: the effects of investment purpose diversity and orientation. Glob Strateg J 7(1):58–82

Grappi S, Romani S, Bagozzi RP (2015) Consumer stakeholder responses to reshoring strategies. J Acad Mark Sci 43(4):453–471

Grappi S, Romani S, Bagozzi RP (2018) Reshoring from a demand-side perspective: consumer reshoring sentiment and its market effects. J World Bus 53(2):194–208

Gray JV, Skowronski K, Esenduran G, Johnny Rungtusanatham M (2013) The reshoring phenomenon: what supply chain academics ought to know and should do. J Supply Chain Manag 49(2):27–33

Gylling M, Heikkilä J, Jussila K, Saarinen M (2015) Making decisions on offshore outsourcing and backshoring: a case study in the bicycle industry. Int J Prod Econ 162:92–100

Halse L L, Nujen B B, & Solli-Sæther H (2019) The Role of Institutional Context in Backshoring Decisions. In International Business in a VUCA World: The Changing Role of States and Firms. Emerald Publishing Limited.

Hartman PL, Ogden JA, Wirthlin JR, Hazen BT (2017) Nearshoring, reshoring, and insourcing: moving beyond the total cost of ownership conversation. Bus Horiz 60(3):363–373

Harzing AW, Alakangas S (2016) Google scholar, scopus and the web of science: a longitudinal and cross-disciplinary comparison. Scientometrics 106:787–804

Hong SJ (2015) When Are International Joint Ventures Too Inflexible to Exit? Acad Strateg Manag J 14(2):59–69

Huang Q, Osabutey EL, Ji J, Meng L (2019) The impact of social networks on “born globals”: a case of de-internationalisation. In: Social entrepreneurship: concepts, methodologies, tools, and applications. IGI Global, pp 911–930

Iurkov V, Benito GR (2020) Change in domestic network centrality, uncertainty, and the foreign divestment decisions of firms. J Int Bus Stud 51(5):788–812

Johanson M, Kalinic I (2016) Acceleration and deceleration in the internationalization process of the firm. Manag Int Rev 56:827–847

Johanson J, Vahlne J-E (1977) The internationalization process of the firm - a model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. J Int Business Stu 8:23–32

Johanson J, Vahlne JE (2009) The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. J Int Bus Stud 40(9):1411–1431

Johansson M, Olhager J (2018) Manufacturing relocation through offshoring and backshoring: the case of Sweden. J Manuf Technol Manage 29(4):637–657

Johansson M, Olhager J, Heikkilä J, Stentoft J (2019) Offshoring versus backshoring: Empirically derived bundles of relocation drivers, and their relationship with benefits. J Purchasing Supply Manage 25(3):100509

Kafouros M, Cavusgil ST, Devinney TM, Ganotakis G, Fainshmidt S (2022) Cycles of de-internationalization and re-internationalization: towards an integrative framework. J World Bus 57(1):101257

Kessler MM (1963) Bibliographic coupling extended in time: ten case histories. Inform Storage Retrieval 1(4):169–187

Kim K (2017) Post-entry on-going organizational changes in core activities of foreign subsidiaries and firm survival. J Appl Bus Res 33(3):489–500

Konara P, Ganotakis P (2020) Firm-specific resources and foreign divestments via selloffs: Value is in the eye of the beholder. J Bus Res 110:423–434

Kotabe M, Ketkar S (2009) Exit strategies. In: Kotabe M, Helsen K (eds) The SAGE Handbook of International Marketing. Sage, London, pp 238–260

Lamba H.K. (2021) Deglobalization: Review and research future agenda using PAMO Framework. In: Paul, J. & Dhir, S. (Eds.) Globalization, Deglobalization, and New Paradigms in Business. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81584-4_1

Lampón JF, González-Benito J (2019) Backshoring and improved key manufacturing resources in firms’ home location. Int J Prod Res 58(20):6268–6282

Lim WM, Rasul T, Kumar S, Ala M (2021) Past, present, and future of customer engagement. J Bus Res 140:439–458

Mandrinos S, Lim WM, Liew CSL (2022) De-internationalization through the lens of intellectual property rights. Thunderbird Int Business Rev 64(1):13–24

Martínez-Mora C, Merino F (2020) Consequences of sustainable innovations on the reshoring drivers’ framework. J Manuf Technol Manag 31(7):1373–1390

McDermott MC (1996) The Europeanization of CPC international: manufacturing and marketing implications. Manag Decis 34(2):35–45

McIvor R, Bals L (2021) A multi-theory framework for understanding the reshoring decision. Int Bus Rev 30(6):101827

Merino F, Di Stefano C, Fratocchi L (2021) Back-shoring vs near-shoring: a comparative exploratory study in the footwear industry. Oper Manag Res 14:17–37

Młody M (2016) Backshoring in Light of the Concepts of Divestment and De-internationalization: Similarities and Differences. Entrepreneurial Business Econom Rev 4(3):167–180

Mohiuddin M, Rashid MM, Al Azad MS, Su Z (2019) Back-shoring or re-shoring: determinants of manufacturing offshoring from emerging to least developing countries (LDCs). Int J Logistics Res Appl 22(1):78–97

Mongeon P, Paul-Hus A (2016) The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: a comparative analysis. Scientometrics 106(1):213–228

Moradlou H, Backhouse C, Ranganathan R (2017) Responsiveness, the primary reason behind re-shoring manufacturing activities to the UK. Int J Phys Distrib Logist Manag 47(2/3):222–236

Moradlou H, Fratocchi L, Skipworth H, Ghadge A (2021) Post-Brexit back-shoring strategies: What UK manufacturing companies could learn from the past? Product Planning & Control. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2020.1863500

Nujen BB, Halse LL (2017) Global shift-back’s: a strategy for reviving manufacturing competences. Breaking up the global value chain (advances in international management), 30. Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp 245–267

Nujen BB, Mwesiumo DE, Solli-Sæther H, Slyngstad AB, Halse LL (2019) Backshoring readiness. J Global Operat Strategic Sour 12(1):172–195

Nummela N, Vissak T, & & Francioni B (2020) The interplay of entrepreneurial and non-entrepreneurial internationalization: an illustrative case of an Italian SME. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, publicado online.

Onkelinx J, Manolova TS, Edelman LF (2016) The consequences of de-internationalization: empirical evidence from Belgium. In: Global entrepreneurship: past, present & future. Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Ozkan KS (2020) International market exit by firms: Misalignment of strategy with the foreign market risk environment. Int Bus Rev 29(6):101741

Paul J, Parthasarathy S, Gupta P (2017) Exporting challenges of SMEs: a review and future research agenda. J World Bus 52:327–342

Peng GZ, Beamish PW (2019) Subnational FDI legitimacy and foreign subsidiary survival. J Int Manag 25(3):100662

Procher VD, Engel D (2018) The investment-divestment relationship: resource shifts and intersubsidiary competition within MNEs. Int Bus Rev 27(3):528–542

Rialti R, Giacomo M, Cristiano C, Donatella B (2019) Big data and dynamic capabilities: a bibliometric analysis and systematic literature review. Manag Decis 57:2052–2068

Robinson PK, Hsieh L (2016) Reshoring: a strategic renewal of luxury clothing supply chains. Oper Manag Res 9(3):89–101

Sadikoglu Z (2018) Explaining the firm's de-internationalization process by using resource-based view. in global business expansion: concepts, methodologies, tools, and applications (pp. 45–58). IGI Global

Sánchez-Pérez M, Terán-Yépez E, Marín-Carrillo MB, Rueda-López N (2021) 40 years of sharing economy research: an intellectual and cognitive structures analysis. Int J Hosp Manag 94:102856

Sandberg S, Sui S, Baum M (2019) Effects of prior market experiences and firm-specific resources on developed economy SMEs’ export exit from emerging markets: complementary or compensatory? J Bus Res 98:489–502

Schmid D, Morschett D (2020) Decades of research on foreign subsidiary divestment: what do we really know about its antecedents? Int Bus Rev 29(4):101653

Sousa CM, Tan Q (2015) Exit from a foreign market: do poor performance, strategic fit, cultural distance, and international experience matter? J Int Mark 23(4):84–104

Steinhäuser VPS, Paula FDO, de Macedo-Soares TDLVA (2021) Internationalization of SMEs: a systematic review of 20 years of research. J Int Entrep 19(2):164–195

Stentoft J, Olhager J, Heikkilä J, Thoms L (2016) Manufacturing backshoring: a systematic literature review. Oper Manag Res 9(3–4):53–61

Su HN, Lee PC (2010) Mapping knowledge structure by keyword co-occurrence: a first look at journal papers in technology Foresight. Scientometrics 85(1):65–79

Surdu I, Narula R (2020) Organizational learning, unlearning and re-internationalization timing: differences between emerging-versus developed-market MNEs. J Int Manag 27(3):100784

Surdu I, Mellahi K, Glaister KW, Nardella G (2018) Why wait? Organizational learning, institutional quality and the speed of foreign market re-entry after initial entry and exit. J World Bus 53(6):911–929

Surdu I, Mellahi K, Glaister KW (2019) Once bitten, not necessarily shy? Determinants of foreign market re-entry commitment strategies. J Int Bus Stud 50(3):393–422

Surdu I, & Ipsmiller E (2021) Old risks new reference points? An organizational learning perspective into the foreign market exist and re-entry behavior of firms. In the multiple dimensions of institutional complexity in international business research (progress in international business research, Vol. 10). Bingley: Emerald, pp. 239–262

Talamo G, Sabatino M (2018) Reshoringin Italy: a recent analysis. Contemp Econ 12(4):381–399

Tan Q, & Sousa C M (2015) A framework for understanding firms’ foreign exit behavior. In entrepreneurship in international marketing. advances in international marketing, 25, 223–238. Bingley: Emerald

Tan Q, Sousa CM (2018) Performance and business relatedness as drivers of exit decision: a study of MNCs from an emerging country. Glob Strateg J 8(4):612–634

Tang RW, Zhu Y, Cai H, Han J (2021) De-internationalization: a thematic review and the directions forward. Manage Int Rev 61:1–46

Thywissen C (2015) Divestiture decisions: conceptualization through a strategic decision-making lens. Manage Rev Quarter 65:69–112

Trąpczyński P (2016) De-internationalisation: a review of empirical studies and implications for international business research. Balt J Manag 11(4):350–379

Turcan R V (2011) De-internationalization: A conceptualization. In Aib-Uk & Ireland chapter conference'international business: new challenges, new forms, new practices.

Van den Berg M, Boutorat A, Franssen L, Mounir A (2022) Intermittent exporting: unusual business or business as usual? Rev World Econ 10:1–26

Van Eck NJ, Waltman L (2014) Visualizing bibliometric networks. In: Ding Y, Rousseau R, Wolfram D (eds) Measuring scholarly impact. Springer, Cham, pp 285–320

Vissak T, Francioni B (2013) Serial nonlinear internationalization in practice: a case study. Int Bus Rev 22(6):951–962

Vissak T, Zhang X (2016) A born global’s radical, gradual and nonlinear internationalization: a case from Belarus. J East Eur Manage Stu 21(2):209–230

Vissak T, Francioni B, Freeman S (2020) Foreign market entries, exits and re-entries: the role of knowledge, network relationships and decision-making logic. Int Bus Rev 29(1):101592

Vissak T (2010) Nonlinear internationalization: A neglected topic in international business research. In Timothy, D., Torben, P. and Laszlo, T. (Eds.) The past, present and future of international business & management. advances in international management, 23, 559–580. Bingley: Emerald.

Wan WP, Chen HS, Yiu DW (2015) Organizational image, identity, and international divestment: a theoretical examination. Glob Strateg J 5(3):205–222

Wan L, Orzes G, Sartor M, DiMauro C, Nassimbeni G (2019) Entry modes in reshoring strategies: an empirical analysis. J Purchasing and Supply Manage 25(3):100522

Wang Y, & Larimo J (2017) Ownership strategy and subsidiary survival in foreign acquisitions: The moderating effects of experience, cultural distance, and host country development. In Verbeke, A., Puck, J. and Tulder, R.v. (Ed.) Distance in International Business: Concept, Cost and Value. Progress in International Business Research, 12, 157–182. Bingley: Emerald.

Wang Y, Larimo J (2020) Survival of full versus partial acquisitions: the moderating role of firm’s internationalization experience, cultural distance, and host country context characteristics. Int Bus Rev 29(1):101605

Welch LS, Luostarinen R (1988) Internationalization: evolution of a concept. J Gen Manag 14(2):34–55

Welch CL, Welch LS (2009) Re-internationalisation: exploration and conceptualisation. Int Bus Rev 18(6):567–577

Whittaker J (1989) Creativity and conformity in science: titles, keywords and co-word analysis. Soc Stud Sci 19(3):473–496

Yadav N, Kumar R, Malik A (2022) Global developments in coopetition research: a bibliometric analysis of research articles published between 2010 and 2020. J Bus Res 145:495–508

Yang JY, Li J, Delios A (2015) Will a second mouse get the cheese? Learning from early entrants’ failures in a foreign market. Organ Sci 26(3):908–922

Yayla S, Yeniyurt S, Uslay C, Cavusgil E (2018) The role of market orientation, relational capital, and internationalization speed in foreign market exit and re-entry decisions under turbulent conditions. Int Bus Rev 27(6):1105–1115

Zhai W, Sun S, Zhang G (2016) Reshoring of American manufacturing companies from China. Oper Manage Res 9(3):62–74

Zupic I, Čater T (2015) Bibliometric methods in management and organization. Organ Res Methods 18(3):429–472

Funding

The research on which this paper is based was funded by CAPES–Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, grant no. 88887.486047/2020–00 and CNPq–Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, grant no. 309410/2021–5.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Luíza Fonseca. All authors have taken place in writing, revising and approving the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

da Fonseca, L.N.M., da Rocha, A. Setbacks, interruptions and turnarounds in the internationalization process: a bibliometric and literature review of de-internationalization. Manag Rev Q 73, 1351–1384 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-022-00276-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-022-00276-7

Keywords

- De-internationalization

- Export withdrawal

- Foreign divestment

- Subsidiary survival

- Backshoring

- Reshoring

- Re-internationalization