Abstract

Grades are the universal tool for measuring students’ performance at school. However, other competency-based evaluation methods have shown to have a stronger impact on the learning quality. We investigated how different methods are collectively represented and discursively constructed among students at an Italian high school class. Thematic analysis was applied to 4 focus groups of about one hour conducted with 18 students (F = 12, M = 6) attending the second year of a scientific high school, at the end of the second year of “At School Beyond the Grade” project. The main themes emerged were linked to the cultural and communicational meanings constructed around each method, showing how they are used for different purposes and yet stay strictly related. Comments were used in a self-reflective manner to improve learning competencies individually. Grades were used to communicate with others their position as a socially shared code. The emerged narratives show the students’ expectations about the way teachers manage evaluation tools and their struggles on translating one into the other. Considerations on the shared ideal of both methods as complementary were discussed in terms of intercultural, identity and learning process.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Learning is the primary purpose of school education but from a student’s perspective the goal is often reduced to one thing: the grade. Although grades are a universal tool for evaluating students, they have been criticized for causing stress, unhealthy competition, and inciting a pattern of learning solely motivated by the pursuit of the highest grade (Kohn, 2011; Mannello, 1964; Pippin, 2014). Furthermore, grades are considered inaccurate tools that can undermine students’ learning and academic progress (Cain et al., 2022; Guskey, 2022) as they are susceptible to teacher bias and could lead to an academic gap between different categories of students (e.g., ethnic minority vs. ethnic majority or gender) (Bonefeld et al., 2022; Costa et al., forthcoming).

To address these issues, gradeless learning has emerged as a promising alternative to traditional grading systems. This approach recognizes that grades can negatively impact student learning, motivation, and relationships with teachers, classmates, and parents. For example, grades can incentivize students to focus on the outcome (the grade) rather than the learning process itself. Furthermore, grades can create a sense of competition and pressure that detracts from the joy of learning and can lead to labels such as “geek” or “loser” (Butera et al., 2011). Instead, gradeless learning emphasizes specific feedback, such as comments, that highlights students’ strengths and areas for improvement, which can motivate and recognize their progress. Comments also provide more detailed information about the student’s understanding and mastery of the material compared to grades, which can be arbitrary and lack nuance. Moreover, going gradeless can help to build stronger relationships between teachers and students (O’Connor & Lessing, 2017), as well as promote a growth mindset that values effort and learning over grades.

From a constructionist approach, discourses can show how people attribute meanings to concepts and therefore act in certain ways, particularly concerning specific terms that need to be analyzed in the interaction among other social actors (Antaki & Widdicombe, 1998; Edwards & Potter, 1992; Gergen, 2001). This process of meaning construction can be observed in a conversation or in a group discussion, and also position the self and attribute roles and expectations to others and of what and how each actor should say or do (Davies & Harré, 1990). Introducing the students’ perspective of the meanings attributed to both grades and comments, as well as the practical uses of them, could be useful for the implementation and improvement of evaluation methods.

This study uses data collected in a longitudinal action-research project at an Italian high school named “At School Beyond the Grade”, which introduces a competency-based evaluation of students in form of comments. The aim of this study is to explore the role of grades and comments in students’ learning attitudes as well as the shared meanings and uses for each one of the methods for the identity construction and as a communicative tool.

2 Grades versus comments

Grades are a widespread method of assessing student performance, used to communicate how well a student has achieved a particular learning goal. They can take the form of letters, numbers, words, symbols, or emojis and are assigned to different levels of student performance. The use of grades can have a significant impact on the classroom environment and can affect various aspects of the students’ experience (e.g., Chamberlin et al., 2023; Poorthuis et al., 2015). For example, receiving a lower grade at the beginning of secondary school can result in less engagement in school later, as well as a lower academic self-concept (Poorthuis et al., 2015). Moreover, grades can shift students’ focus and motivation. Pulfrey et al (2011) found that grades can lead to the adoption of performance-avoidance goals among students, which can have negative consequences for student motivation and engagement. When students adopt performance-avoidance goals, they focus on avoiding negative evaluations rather than on pursuing their own interests or learning goals, which can lead to decreased engagement and a lack of interest in the material being taught. In other words, grades can have a negative effect on students’ interest in a subject. Harackiewicz et al. (2002) found that when students were given a choice between an easy task with a high grade or a challenging task with a lower grade, they were more likely to choose the easy task, even if it was less interesting. This suggests that grades can lead students to prioritize external rewards over their own interests and curiosity. In another study, Pulfrey et al (2013) compared a standard-graded condition and a non-graded condition. Although both conditions resulted in equivalent levels of achievement, the no-grade condition showed higher levels of perceived task autonomy. This led to increased task interest and higher levels of continuing motivation for the task. The study suggests that grades can have negative effects on students’ intrinsic motivation, but these effects can be mitigated by allowing students to maintain a sense of autonomy in their learning. When students feel they have more control over their learning process and are not solely evaluated based on their grades, they are more likely to feel interested in the task and continue engaging in it, even after external incentives like grades are removed. Therefore, the absence of grades can lead to higher levels of perceived task autonomy, which, in turn, leads to higher levels of task interest and continuing motivation for the task.

Furthermore, student motivation and engagement are integral aspects of pursuing higher education (Passeggia et al., 2023). In Italy, where the university dropout rate ranks among the highest in Europe (AlmaLaurea, 2020) and the number of graduates is notably low (OECD, 2019), it’s crucial to recognize the possible role of grades in this process (Aina et al., 2022). Low grades and academic performance can often contribute to a student’s decision to drop out, even if the decision to drop out evolves gradually (Contini & Salza, 2020). Particularly, a substantial number of dropouts occur in the initial year of college (Del Bonifro et al., 2020), underscoring the pivotal role of the high school period in this decision-making process. A recent study by Passeggia et al., (2023) examining Italian college students demonstrates a significant relationship between autonomous motivational styles, academic performance, student engagement, and the likelihood of dropout.

Research has shown that grades can lead to an unhealthy atmosphere and negatively affect the relationship between students and teachers and between peers (Chamberlin et al., 2023; Guskey, 2019). Grades can create a competitive atmosphere in the classroom, leading to a focus on individual performance rather than cooperation and collaboration (Rohe et al., 2006). This can result in negative peer relationships and a lack of support for struggling students, and can negatively affect the teacher-student relationship (Chamberlin et al., 2023). Furthermore, students who receive lower grades may feel stigmatized or unfairly judged, which can damage their self-esteem and sense of belonging in the classroom (Butera et al., 2011).

Overall, these negative effects of grades on the classroom environment suggest that there is a need to explore alternative assessment methods that can promote collaboration, engagement, and intrinsic motivation. These arguments led some scholars to argue for the use of gradeless systems, which prioritize feedback and self-reflection over numerical scores (Barnes, 2018; Burns & Frangiosa, 2021; Kohn, 2011; Spencer, 2017).

A gradeless approach to education involves providing feedback in a valid and evaluative manner that can allow students to better understand their skills and progress. This approach can include providing comments, which offer detailed feedback on specific skills and areas for improvement. Descriptive feedback “enables the learner to adjust what he or she is doing to improve” (Davies, 2007, p. 2). Percell (2017) describes “purposeful feedback that is process-oriented, personal, informal, and genuine”, and which is “foundational to sustaining a relationship of confidence and trust” to “ensure student growth and an improved quality of work” (p. 115). McMorran et al. (2017) defined gradeless learning a system where students are assessed based on a pass/fail, credit/no credit, or qualitative evaluation rather than receiving a numerical grade.

Guskey (2022) proposed four conditions that ensure effective feedback. The first condition is related to the object of the feedback: it should be assigned to performance rather than to students. Teachers’ feedback should not define students’ identity as learners, but rather indicate their progress in the learning journey, and grades often fail in this, as they are more perceived as identity label than a guidance for students learning (Martins & Carvalho, 2013). The second condition states that feedback must be criterion-based and not norm-based. Norm-based grades refer to a standardized assessment that compares students to their classmates, that lacks meaningfully communicating about their learning and competences. A criterion-based approach involves a form of feedback that aims to describe how well students have achieved learning goals. This way, feedback is not related to the position of the students among peers and fosters an environment in which the students compete against themselves to achieve learning objectives, rather than against each other. Although grades alone may not meet this condition, teacher comments can effectively achieve this goal. According to the author, the third condition for effective feedback concerns its temporary nature. To accurately describe the level of student learning, feedback should be temporary, as the level of student performance is always subject to change. In other words, feedback must reflect the current level of student performance, rather than a permanent or fixed level of ability. The last condition for feedback to be effective is to provide guidance for improvement. Grades simply reflect an appraisal of students’ current level of performance, and do not offer the necessary detailed information for students to identify their specific strengths and weaknesses. Therefore, in order to be useful for students, feedback must be individualized, based on students’ unique learning needs (Bloom, 1968). Grades appear insufficient for students’ learning (Hattie & Timperley, 2007), as they do not provide all the information students need. By providing comments, teachers have the opportunity to provide informative and supportive feedback to their students, helping them to develop a deeper understanding of their performance, encouraging their growth and learning, and providing individualized guidance to support their progress.

In one of the earliest study about this topic, psychologist Ellis Page (1958) explored the impact of grades and teacher feedback on student achievement. In the study, teachers evaluated their students’ work and then divided them into three groups. The first group received only a grade. The second group received standardized comments along with the grade, and the third group received individualized comments and instructional practices. Results showed that students who received standard comments with their grades scored significantly higher on the next assignment they were given, than those who only received a grade, and students who received individualized comments performed even better. This study demonstrated that grades alone do not help students in their learning, whereas individualized comments can improve their achievement and performance, and are beneficial for the student learning process.

But how do teachers feel about gradeless feedback? McMorran and Ragupathi’s (2020) survey, conducted at a Singaporean university offering gradeless assessment to first-year students, revealed that while teachers recognized the advantages of gradeless learning for their students, they had reservations about its benefits for themselves. However, even when gradeless assessment is perceived as too challenging or unconventional, teachers may be motivated by other factors. In fact, in a study conducted by Whitmell (2020), the interviewed teachers described concepts of assessment that revolve around the learner, emphasizing pedagogical approaches that support student voice and choice. These educators faced challenges stemming from cultural expectations held by students, parents, and colleagues. However, it’s noteworthy that none of the interviewees were constrained by policy requirements when implementing the changes in assessment practices they identified as “gradeless”, aiming to enhance their students’ learning experiences over the school evaluation system. The study proposes that teachers’ conceptual understanding of assessment originates from their personal experiences and is further shaped by the pedagogy they employ, the cultural influences within their professional and school community, and the policies that guide their practice. Additionally, the research highlights that when teachers discover processes that enhance their students’ achievement, they persevere with these new approaches even when confronted with strong cultural pressures. This underscores the need for greater communication and education within the school community, to shift cultural expectations surrounding assessment.

Teachers play a central role in developing pedagogical innovations that de-emphasize grades as a measure of learning motivation, and their involvement is crucial for the success of gradeless assessment, regardless of the educational institution or grade level (Johnson, 2022). To fully implement gradeless assessment, teachers should embrace innovation in both mindset and practice, shifting the focus from valuing grades to recognizing the time learning takes and encouraging creativity over conformity.

Comments not only give the student more information about their work, but allow the teacher to communicate a message, and this may be what matters most (Guskey, 2019). In contrast, grades fail to convey information about what a student has learned or is capable of. High grades may not necessarily reflect the achievement of learning goals but rather superior performance relative to peers.

The impact of using grades or comments in assessments can vary significantly depending on the different levels of education and contexts, as well as the diverse age groups of students. In a recent meta-analysis Koenka et al. (2021) showed the unique consequences of grades for elementary versus high school students. For high school students, the impact of grades proved to be more detrimental to their motivation, resulting in diminished intrinsic motivation and heightened extrinsic motivation when compared to their non-graded peers. In contrast, elementary students consistently reported similar levels of internal motivation, regardless of whether they received grades or not. Additionally, it is noteworthy that secondary students are more prone to identify themselves as students, and therefore grades may hold a substantial influence on their academic identity (Yukhymenko-Lescroart & Sharma, 2022).

The debate around grades versus comments is wide (Guskey, 2019), with some arguing for the elimination of grades and the use of just comments to provide feedback (Barnes, 2018; Kohn, 2011; Spencer, 2017), while others believe that grades are necessary to report students’ progress and prove their competences (Brookhart & Nitko, 2008). However, although there is a long history of research on this topic, the results are still unclear and definitive conclusions have yet to be drawn. The complexity of the relationship between students and feedback highlights the need for teachers to provide effective evaluations that can positively affect students’ academic performance without negatively affecting their identity development. Studying the meanings that students attribute to different forms of feedback can be crucial for this purpose.

3 Teachers’ feedback and students’ identity

High school is a crucial stage in life where adolescents develop their identity (Erikson, 1994; Verhoeven et al., 2019). Teachers can significantly impact this process in various ways. A recent literature review by Verhoeven et al. (2019) analyzed 111 studies to gain insight into the role of schools in adolescent identity development. The findings revealed the unintended impact of teachers on adolescents’ identity development through teaching strategies and expectations. As a result, teachers’ feedback can have an impact on students’ identity (Yukhymenko-Lescroart & Sharma, 2022), as teachers’ expectations are also reflected in their grades (Costa et al., forthcoming). Negative feedback from teachers might be perceived as a label, such as “bad student”, and the consequences of these experiences in adolescence are long-lasting through the academic path (Freire et al., 2009; Inouye & McAlpine, 2017). In any case, both negative and positive feedback serve as a source of information on students’ self-perception (Martins & Carvalho, 2013). Adolescents require also interaction with their peers to construct their identity (Ragelienė, 2016), and the discussion of different feedbacks may contribute to the formation of their identity in unique ways.

Feedback, according to Hattie and Timperley (2007), is defined as “information provided by an agent (e.g., teacher, peer, book, parent, self, experience) regarding aspects of one’s performance or understanding” (p. 81). Their feedback model emphasizes the significance of feedback in shaping the formative process through questions such as “Where am I going?”, “How am I going?” and “Where to next?”. Feedback, in this way, links personal and formative experiences across time, encompassing the past, present, and future (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999). As a result, this connection may impact how students perceive and construct their experiences at school and their identities as students. As they negotiate the meaning of their experiences in school, they also define and shape their identities. Therefore, the quality of the feedback is critical in the formation process, as the content is crucial to its effectiveness. Feedback that helps students reject incorrect ideas and guides them in finding new strategies is the most beneficial, particularly when it addresses self-regulation (Hattie & Timperley, 2007). This type of feedback leads to increased engagement, confidence, and investment of effort in learning. The affective dimension of feedback also plays a crucial role in shaping students’ interpretations of themselves as learners (Hattie & Timperley, 2007).

These interpretations, in turn, may shape students’ identities, influences the decisions they make in school and how they position themselves in the class and school community (Freire et al., 2009; Holland et al., 2001). Positional identity refers to a person’s understanding of their social position in a given environment and their access to resources, activities, and voices based on their interactions with others (Holland et al., 2001). In the educational setting positional identity can be shaped by grades that assign labels and categorize the individual. Therefore, a competency-based evaluation provides students with more informative and effective feedback than a simple grade (Guskey, 2019).

However, these studies do not take into consideration the subjective process of meaning-making and identity positioning that can be analyzed in the discursive construction, for instance, within a classroom: concepts such as grades and comments can be object of discussion and debate, as well as how these tools are being used and for which purposes. In this sense, a situated perspective that explores the communicative function when interacting with teachers, other students, or parents, udents’ experiences regarding different evaluation modes.

4 “At School beyond the grade”: an action research project

“At School Beyond the Grade” is a longitudinal action-research project started during the academic year 2020/2021 aimed at promoting a shift in students’ assessments by prioritizing the development of students’ key competencies, over the traditional focus on grades and test scores, by the introduction of a competency-based evaluation provided by professors instead of numerical grades. It involved a class of 33 students attending the first year of an Italian High School located in a central region, with a science-oriented educational framework and 8 teachers. Italian school system relies on a combination of summative grades and continuous assessment to evaluate student performance. The project was promoted by the school itself and it’s still ongoing. The researchers were involved by a teacher with a coordination function and the school principal with the request to monitor the progress of the innovation, to support the experimental class teachers and to help to communicate with the students and their parents about the changes in evaluation practices.

Ethical approval was obtained by “Roma Tre” University committee and all participants gave informed consent to participate.

From September 2020 to December 2020, monthly training meetings, workshops and supervision meetings for the teachers were scheduled, to train and support them in the transition from “grades” to “competency-based evaluation”, both theoretically and practically. All the meetings were conducted by an experienced researcher and trainer among the authors. At the beginning of the school year, both students and parents were informed by the school about the project and its implementation. The research team met the students and the parents (separately) twice in the first year of the project to discuss the challenges and benefits of competency-based evaluation.

In March 2022, during the second year of the project, four online focus groups (FGs) were conducted with students to investigate the progress of the intervention and explore their representations of competency-based evaluation and grades. Given the explorative nature of the study, the research questions that guided the conduction of the FGs were formulated to delve into the evolving dynamics of evaluation within the classroom setting. Therefore, the research questions that guided the conduction of the FGs were:

-

(1)

How are different modes of evaluation being represented and discursively constructed within a classroom group?

-

(2)

What are the main themes that are discussed linked to each mode of evaluation?

By answering these research questions, we aimed to explore the content of the discussion, the thematic organization of their narratives regarding grades and competency-based evaluation (or comments, the term used by students to refer to it) and the identity positioning of students looking at the rhetoric and discursive construction about the meanings and uses of these in social relations with others and in the situated negotiation of meaning construction.

5 Methodology

Participants were 18 students (F = 12, M = 6) enrolled at the second year of High School at the time of focus groups (Table 1). The focus groups were held outside school hours. Participants were randomly divided into 4 smaller group. Two focus groups were attended by 4 students and two focus group by 5. The decision to conduct different focus groups with smaller groups was made to maximize participant expression. Previous class meetings revealed a tendency for a small number of students to lead group discussions, potentially limiting the range of perspectives and experiences conveyed. In contrast, the use of smaller focus groups allowed for greater representation and a more equitable distribution of speaking opportunities among participants. As a result, a broader range of opinions and experiences were captured, providing a more comprehensive understanding of their experience.

The focus groups were conducted by a moderator (a researcher engaged in the project), and an observer, using the online platform Zoom. Discussions were audio and video-recorded and then transcribed verbatim. The average length of focus groups was 35.25 min.

The track of the focus group was based on the previous responses given to an online questionnaire that aimed to investigate satisfaction and issues related to the gradeless assessment mode. The main themes proposed for the discussion during the focus group were the overall satisfaction related to the experience of being involved in the project and having experienced different modes of assessment; positive and negative/critical aspects of both modes; representations of competency-based evaluation and grades; and ways and purposes of using competency-based evaluation and grades (see “Appendix A” for the specific questions that guided the discussions).

Two distinct analyses were undertaken—a Thematic Analysis and a Discourse Analysis. The thematic analysis involved the systematic examination of the data to identify overarching themes. This approach aimed to uncover the fundamental concepts and recurrent ideas that emerged from the focus groups. It consisted of two steps with an increasing level of systematicity to ensure a thorough and comprehensive analysis of the data. The first step of the thematic analysis consisted in reading the data (all 4 FG) were iteratively read by two codifiers independently in order to identify the main themes discussed, including the expected ones of the track and others that spontaneously emerged following a bottom-up approach (Braun & Clarke, 2012). After confrontation between the two codifiers, the manual coding resulted in the following main themes: functionality; student positioning; communication; social actors; representation and usage. The second step of the thematic analysis was conducted using the software Atlas.ti 22, with the purpose of enriching the previous themes with detailed sub-themes and sub-categories, so data was further coded by two independent analysts labelling the single extracts. This allowed us to explore in detail, for instance, which social actors were involved when talking about one or another method, how both methods were used/represented in everyday life, in which position students were (agency) when interacting with teachers or parents, and if methods were introduced as obstacles or resources through the discourse. See Table 2 for the detailed coding system.

Finally, Discourse Analysis (e.g., Davies & Harré, 1990; Potter, 2013) was conducted to explore the rhetoric construction and identity positioning of participants in the relevant excerpts related to the main themes emerged. Through DA the intercultural dynamics, consensus, and conflict negotiation within the FGs were analyzed. Results of the overall analysis were then represented in a thematic map that sums up the main themes, relations and uses of them, combining both thematic and Discourse Analysis.

6 Results

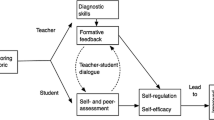

Results have shown the main themes around the meanings, representations and discursive uses of grades and comments. The thematic analysis of the FGs resulted in two macro-themes regarding comments and grades, strictly related with each other by a third theme that regards the translation/interpretation of the comment into grade (see Fig. 1).

6.1 Comments: a new challenge to be interpreted

From the perspective of the participants, the action research introduced a ‘new’ way of communicating the evaluation of teachers delivered to the students (based on the evaluation of competences / comments), as opposed to the 'old' way of using grades. This intervention has triggered students to actively reflect on their evaluations (agency), whether in an introspective manner or in sharing it with others. In the last case, translation into a grade (a recognized label that positions the self in a ranking) becomes inevitable:

Maybe I wanted to compare myself with friends, because … I wanted to compare myself maybe on some judgments and some grades and I was struggling in that sense, report something that was only being done in my class and not in the rest of society… I was doing something different. I felt like an outsider in that sense.

Maybe my parents see the comment, maybe they ask ‘so… how much is it? would it be enough or not enough?’. I mean that's the thing, in the end ... they just ask you if it's a sufficiency or if it’s a non-sufficiency. They always just ask you ‘ah, but so what grade is it?’

Comments made by teachers (as the social actors delivering such evaluation) are restricted to a limited time (in itinere) and space (in classroom) and therefore acquire value and meaning only for students. Indeed, participants reported that Competence-based evaluation is hardly used to communicate with others and therefore can cause a sense of alienation (“an outsider” when communicating with friends or parents), yet at the same time, its strength is seen in the potentiality of enabling a positive change in the study path:

There are positive sides in the comment. In fact, such as showing you what you need to improve

However, I think that the comment is important because it helped me anyway, over time to see where I was doing wrong, to improve the strengths, and where I am most lacking

The lines reported above show an active agency of students, a reflexive stance that is considered to be a resource. In other excerpts, the functionality of comments as a resource is linked with a certain kind of comment, that is: when they are tailored to the student, rich and detailed, and when it triggers some kind of improvement in the students’ competencies. But comments can also be an obstacle, if they remain vague, indecipherable and lead to misunderstandings. The unpredictability of the comments’ meanings create surprise and even anxiety (as reported by some participants).

Sometimes with the comments you can be wrong and... you’re not sure. In fact, last year for the end-of-year report, and again this year for the end-of-semester report, I had a few surprises... grades that I didn’t expect.

Since then you have this problem that at the end of the year you have the number [grade], there is always the uncertainty… ‘but am I sure that this is what I will have at the end of the year?’

Further, participants reported that sometimes comments are written in standardized or random ways (generalized to all students), in which cases the added value of this method of evaluation remains missing.

For example, some professors tell you, medium-high level, right? But what is medium-high level? Eight, nine? And then high level. High level is what? Ten or nine? […] So maybe it should be written also what you did wrong, what you have to revise. not in a general way, but more specifically

In some cases, students’ unsatisfaction of “copy and paste” comments became almost an instance of complaint and accusation of teachers not knowing how to use this kind of evaluation.

The comment, however, was supposed to be something that the teachers were committed to, and by providing these comments, they truly helped you understand. Then it became something done randomly, with copied pieces transcribed onto the record.

So, one can tell that it’s a copy-and-paste… there was, for example, an examination where three of us compared feedback and we all received the exact same copy-and-paste comment in two lines. Some Professors put more effort into the comments, while others treated it like ‘Ok, I have to include a comment, so I’ll just copy and paste it.’

6.2 Grades: the usual code for positioning and communicating with others

Grades, on the opposite side, are the usual output of evaluation, it is recognized by participants as “the way it always has been done” and the output expected by society (parents, friends, education, work). It worked fine until now and it is still requested after high school, whether for pursuing a scholarship or a job position.

Exactly, maybe a person also wants to take I don’t know a scholarship and they need to have a certain average [grade], um... they have to have precisely a certain level to take it, in short

Grades therefore are used to position oneself in context and in relation to others (comparability), and by doing so, it is also a way of constructing the self (identity), creating expectations in social contexts and the commitment to keep a certain level of educational success.

I personally think that the grade is a little bit of a category... if you maybe get 10 you’re in the top category, if you get maybe 7 and you’re a little bit lower, I've always seen it that way since elementary school

We find ourselves placed in a level to reach certain jobs, for example. I mean... in a company, someone with a level of 10 may become a director, while someone with a level of 6 might become a labourer, that’s what I meant.

Finally, grades are considered to be an obstacle in cases in which this mode of evaluation does not trigger a real improvement of the learning method, that is, if it remains the only standard way of evaluation (see Fig. 1), or in cases in which the grade encapsulates the identity of the student under a single label.

Since we were little, we were always told that if you get a 10, then yes, you’re excellent, you’re really good. But, if you maybe get a 6, hmm... you might not be that great, no, you always have to aim for more.

6.3 Between comments and grades: complementary ways of giving meaning to evaluation

Narrated as a fixed label attached to students’ identity, grades can be a source of stress, and are being described from a passive position in which there is no space for interpretation or elaboration. Instead, the active process of decryption and comprehension required by comments makes all the process smoother and with “less impact” than grades (see excerpt above):

Seeing there 4 and a half to me was a shock, I burst into tears and delirium happened at home. On the other hand in the last drawing [subject] test, it was bad, but reading the comment, is different from a 4 and a half, that is, the difference between comment and grade is […] It gives less impact than the grade splattered in front here, something like that With the comments, it’s easier to understand your skills and what you’ve done wrong, rather than having a grade that just defines you.

Participants state that the grades have a stronger impact than the comments because it is immediately comprehended as a universal code. Comments, on the other side, require a deeper interpretation:

Sometimes yes, and sometimes they seemed to me, more vague, because I couldn’t understand what they actually meant, and what precisely I could improve, besides specific content. But I also wanted to know about the general, such as my study method, what I could improve and some advice

Some comments can make us understand a lot more than a grade that ‘ah! That’s the grade’... I mean, come on. But there are very misunderstandable ones, … the comments are very misunderstandable ((laughs))

The liminal space between comments and grades regards precisely the theme of the translation (see Fig. 1), which means that the comment is not enough for them to understand and cannot be communicated to others. Participants feel the need to understand, besides the comment, if they have reached the threshold or not.

Since at the end of the year there are numerical grades anyways, Uhm… we are very anxious regarding precisely our average, what final grade I will have.

The grade I think … I mean at least for me it represents an anxiety because, anyway I know that at the end of the year that grade, it will pretty much represent the path of my summer.

At the same time, comments allowed them to improve by reflecting deeper on the methods of study, which implies a bidirectional relation between comment and grade as complementary ways of evaluation.

Interestingly, the feelings and emotions emerged and introduced in the focus groups regard this precise process of interpretation and mediation space. anxiety, insecurity, feeling strange and surprised characterized this stance of not clearly knowing where and how one is positioned in a wider educational path as a result of a “lost in translation” sensation. That is why an integrated evaluation is considered to be a resource and the ideal method of evaluation only if comments contain detailed and personalized analyses and if both grades and comments can be successfully translated and comprehended (see Fig. 1).

Because it is 100% complete. You can tell what grade you got, what you need to improve, what you did wrong. Yes, I think it’s the most complete one

To improve my study method, I believe that the best feedback is the comment, at a practical level, is necessary to understand what grade you have, so also the numerical grade, of course. Therefore, I think that both should be used because they serve two different purposes and are both useful.

So, during these 2 years, my anxiety about the numerical grade has disappeared. However, in its place, another anxiety has emerged, which is the ability to interpret the judgments of some professors. [...] So maybe alongside the comment, the numerical grade would also be useful to better understand.

Speaking directly to teachers in order to ask for further explanations may be the extreme solution for most of participants, in case of incomprehension.

I think like them [comments with grades is the ideal method of feedback], but with the addition of a conversation with the professor in class to discuss the issues encountered during the assessment.

Comments plus grades evaluation are therefore considered as a strong resource because it gives the opportunity to students to reflect in detail in a more complex and in-depth way on how to improve, while at the same time it offers a recognized code that can be easily shared with others to communicate at what level a student may be positioned within a learning process.

7 Discussion and conclusion

These findings make a distinctive contribution to the literature on “gradeless” learning. By using a qualitative approach, we were able to explore the students’ meanings of two kind of evaluation feedback (grades and comments) at an Italian high school, providing a detailed and empirical contribution of the functions of evaluations and emotions about different evaluation modes, exploring the students’ perspectives.

The fact that the thematic analysis provided three different main themes (grades; comments; grades and comments as ideal) shows that there are different meaning paths, worlds of words, that are discursively motivated by participants. Through examples and anecdotes, students acknowledged the potentialities and limitations of each evaluation method and how they are used for different purposes. Moreover, the subjectivity of the ways teachers can make use of such comments blurs the categorization process, while recognizing the power of these actors in communicating effectively or not. This kind of interactional process between students and teachers shows clearly that the meaning of the evaluation method the meaning of evaluation methods is co-constructed through dynamic negotiation between students and teachers, revealing the identity construction processes at work in educational contexts. As in other cases (e.g., Norton & Fatigante, 2018), exploring the discursive construction of meanings attributed in educational contexts brings forward the identity construction of students and teachers as ways of positioning one in relation to the other in situated contexts (e.g. in the classroom, at the evaluation time). By using this kind of analysis, it was possible to observe the dynamic negotiation that is entailed behind such meanings and its intercultural nature (Norton, 2020), and how power relations influence how evaluation methods are perceived and used. As an example, communicating a grade to parents will almost automatically be comprehended and “translated” into effective actions, whether being congratulating or punishing students as feedback, whereas the social actors involved in the interaction will position themselves accordingly, also, to power relations.

Interestingly, struggling in comprehending a comment or a grade can provoke stress and anxiety, as reported by participants in this study. This is an intriguing finding, given that the literature would suggest a relationship between negative emotions and grades (Pekrun et al., 2023). Accordingly, one might have expected such negative emotions to be alleviated by replacing grades with comments. On the contrary, anxiety was not directly linked to the grades themselves. Rather, it appears that uncertainty surrounding the translation of comments into grades is what gave rise to this feeling. Therefore, it is possible that the origin of the anxiety generated by evaluations sets in the misunderstanding and non-communicability of the feedback, whether it is a grade or a comment.

In this process, we cannot overlook that the efficacy of assessments is intricately entwined with the quality of instruction, clarity of guidelines, the degree of student engagement, and the holistic teaching approach employed (Burić & Kim, 2019). In recognizing the multifaceted nature of the educational environment, it becomes evident that the evaluation process is not a standalone entity but an integral part of the broader educational context. It is imperative to acknowledge that teaching methods can significantly impact students' responses to evaluations, encompassing both numerical grades and qualitative comments. Moreover, despite recognizing the challenge that teachers face in aligning assessment tests with learning experiences, the specific exploration of the relationship between teaching methods and assessment was not a focal point during the research period, and it was not discussed in any student focus group sessions.

Comments are presented as more intimate, because they are directed and can be comprehended mainly by the student and thus trigger an individual process of auto-evaluation while decoding the meaning of it. Indeed, it requires a longer and deeper process and probably this is the learning effect of the reflexive stance. Individualized feedback in the form of comments allows students to improve their study method and adopt an approach driven by competency goals instead of performance goals, which is not the case when they receive a simple grade. On the other hand, the need for the grade to socially position themselves emerges. It remains for them a clear indicator of academic performance, and closely connected to their identity, in school and out. In any case, comments were linked to an active reaction, while grades were represented as the final end of the evaluation, a more defined and fixed label.

The focus groups conducted in this study did not reveal any themes related to competition or cooperation among students. This suggests that the absence of grades did not significantly alter the dynamics and relationships among students in the classroom. These findings are in contrast to some previous research (e.g., Guskey, 2022; Spencer, 2017), which has suggested that the presence of grades can lead to an unhealthy competitive environment and negatively affect social dynamics in the classroom. While the removal of grades might have been expected to lead to less competition, as students would no longer have to compare themselves to others based on grades, this did not emerge as a significant factor in the focus group discussions.

Although the focus groups did not explicitly mention motivation as a significant issue related to grades, it is important to consider the potential negative effects of grades on student motivation and engagement in the learning process. Previous research (Harackiewicz et al., 2002; Pulfrey et al., 2011) has suggested that grades can lead students to adopt performance-avoidance goals, where they focus on avoiding negative evaluations rather than pursuing their own interests or learning goals. It is possible that the students in the focus groups were not explicitly aware of the connection between grades, comments and their motivation, and the focus groups was not designed to elicit discussions specifically about motivation, so this theme may not have emerged naturally. Moreover, it is also possible that the students did not see motivation as a significant issue, or that other themes related to grades and comments were more salient to them. Different students may have different attitudes towards grades, and may be influenced by factors other than motivation, such as competition, self-evaluation, or the need for external validation. However, while motivation may not have been a prominent theme in our focus groups, it is still an important consideration when discussing the potential drawbacks of grades.

The results not only showed what representations and uses of each mode are being constructed, but also what students expect. Two main considerations should be acknowledged in this regard. Firstly, the complementary capacity of both grades and comments showed an intercultural capacity of students in dealing with categories and blurred spaces that can be decoded but that, at the same time, allow change and progress. Both are needed to improve their learning skills and capacities. Secondly, it is important to note that there are not such things as evaluation modes if we don’t consider who is using them and how. Each evaluation mode requires a person (teacher) that also attribute meanings and purposes for using them.

These last considerations suggest expanding the research to different contexts and involve different social actors, such as teachers and parents, who are the privileged interlocutors of students. Further developments could also include the societal dimension of evaluation, going from a situated perspective to a cultural and societal one.

It is important to note that these findings only reflect the implementation of competency-based evaluations at one school, and thus are not necessarily generalizable to other groups of students. However, data suggest educational implications toward evaluation that provides students with a higher quality of information, enabling them not only to position themselves and communicate their educational path to others, but also to guide their own learning actions.

If we contextualize our findings within the specific framework of Italy’s educational system, which heavily relies on numerical grades, spanning from primary schools to post-graduate specialization courses, it appears clear how this grade-centered system corroborates the deep connection between students’ identity, their numerical grade, and their projections towards future opportunities outside of the educational sphere. For example, in Italy, a student’s grade plays a pivotal role in determining their eligibility for various courses and university admissions, as well as to apply to certain (in particular public) job offers. However, our research highlights a new perspective. Our findings reveal that while the numerical grade holds significance in the Italian education system and for students’ identity, it is not the most effective tool for fostering knowledge growth. Instead, our findings advocate for the annotated assessment approach as a more congruent method with the educational objectives of schools. Comments and competency-based evaluations provide a more nuanced and comprehensive evaluation of a student’s performance, promoting a deeper understanding of their strengths and areas that require improvement. These insights carry vital implications for educational policies. It is crucial that policymakers consider how a transition from a purely grade-centric system to one that incorporates comments evaluations could align more closely with the broader educational goals. This shift can potentially empower students with a richer understanding of their educational path and better prepare them for the demands of higher education and the workforce. By emphasizing the significance of qualitative evaluations alongside numerical grades, Italy could move towards a more holistic and student-centered education system.

References

Aina, C., Baici, E., Casalone, G., & Pastore, F. (2022). The determinants of university dropout: A review of the socio-economic literature. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 79, 101102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2021.101102

AlmaLaurea. (2020). XXII indagine-profilo dei laureati 2019 [XXII investigation-profile of 2019 graduates]. https://www.almalaurea.it/i-dati/le-nostre-indagini/profilo-dei-laureati.

Antaki, C., & Widdicombe, S. (1998). Identities in talk. Sage.

Barnes, M. (2018). No, students don’t need grades. Education Week, 7–74.

Batten Page, E., & Page, E. B. (1958). Teacher comments and student performance: A seventy-four classroom experiment in school motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 49(4), 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0041940

Bloom, B. S. (1968). Learning for mastery. Evaluation Comment, 1(2), 1854–1854. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_4645

Bonefeld, M., Kleen, H., & Glock, S. (2022). The effect of the interplay of gender and ethnicity on teachers judgements: Does the school subject matter? The Journal of Experimental Education, 90(4), 818–838. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2021.1878991

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper (Ed.), APA hndbook of Research methods in psychology: Research designs (Vol. 2, pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-004

Brookhart, S. M., & Nitko, A. J. (2008). Assessment and grading in classrooms. Pearson College Division.

Burić, I., & Kim, L. E. (2019). Teacher self-efficacy, instructional quality, and student motivational beliefs: An analysis using multilevel structural equation modeling. Learning and Instruction, 66, 101302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.101302

Burns, E., & Frangiosa, D. (2021). Going Gradeless, grades 6–12: Shifting the focus to student learning. Corwin Press.

Butera, F., Buchs, C., & Darnon, C. (2011). L’évaluation, une menace? [Evaluation, a threat?]Presses Universitaires de France. https://doi.org/10.3917/puf.darno.2011.01

Cain, J., Medina, M., Romanelli, F., & Persky, A. (2022). Deficiencies of traditional grading systems and recommendations for the future. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 86(7), 908–915. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe8850

Chamberlin, K., Yasué, M., & Chiang, I. C. A. (2023). The impact of grades on student motivation. Active Learning in Higher Education, 24(2), 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787418819728/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/10.1177_1469787418819728-FIG1.JPEG

Contini, D., & Salza, G. (2020). Too few university graduates. Inclusiveness and effectiveness of the Italian higher education system. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 71, 100803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2020.100803

Costa, S., Glock, S., & Pirchio, S. (forthcoming). The effects of implicit ethnic expectations and burnout on teachers’ evaluations of students’ performance. Manuscript Submitted for Publication.

Davies, A. (2007). Making classroom assessment work (2nd ed.). Connections Publishing.

Davies, B., & Harré, R. (1990). Positioning: The discursive production of selves. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 20(1), 43–63. Positioning: The discursive production of selves. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.1990.tb00174.x

Del Bonifro, F., Gabbrielli, M., Lisanti, G., & Zingaro, S. P. (2020). Student dropout prediction. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 12163 LNAI, 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52237-7_11

Edwards, D., & Potter, J. (1992). Discursive psychology. Sage Publications Inc.

Erikson, E. H. (1994). Identity youth and crisis. W.W. Norton Company.

Freire, S., Carvalho, C., Freire, A., Azevedo, M., & Oliveira, T. (2009). Identity construction through schooling: Listening to students’ voices. European Educational Research Journal, 8(1), 80–88. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2009.8.1.80

Gergen, K. J. (2001). Social construction in context. Sage.

Guskey, T. R. (2019). Grades versus comments: Research on student feedback. Phi Delta Kappan, 101(3), 42–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721719885920

Guskey, T. R. (2022). Can grades be an effective form of feedback? Phi Delta Kappan, 104(3), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/00317217221136597

Harackiewicz, J. M., Barron, K. E., Tauer, J. M., & Elliot, A. J. (2002). Predicting success in college: A longitudinal study of achievement goals and ability measures as predictors of interest and performance from freshman year through graduation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(3), 562–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.3.562

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

Holland, D., Lachicotte, W. S., Jr., Skinner, D., & Cain, C. (2001). Identity and agency in cultural worlds. Harvard University Press.

Inouye, K. S., & McAlpine, L. (2017). Developing scholarly identity: Variation in agentive responses to supervisor feedback. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 14(2), 3. https://doi.org/10.53761/1.14.2.3

Johnson, R. E. (2022). Gradeless assessment: Improving engagement and motivation in high school classrooms. Thompson Rivers University.

Koenka, A. C., Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., Moshontz, H., Atkinson, K. M., Sanchez, C. E., & Cooper, H. (2021). A meta-analysis on the impact of grades and comments on academic motivation and achievement: A case for written feedback. Educational Psychology, 41(7), 922–947. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2019.1659939

Kohn, A. (2011). The case against grades. Educational Leadership, 69(3), 28–33.

Mannello, G. (1964). College teaching without grades: Are conventional marking practices a deterrent to learning? The Journal of Higher Education, 35(6), 328–334.

Martins, D., & Carvalho, C. (2013). Teacher’s feedback and student’s identity: An example of elementary school students in Portugal. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 82, 302–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.265

McMorran, C., & Ragupathi, K. (2020). The promise and pitfalls of gradeless learning: Responses to an alternative approach to grading. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(7), 925–938. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2019.1619073

McMorran, C., Ragupathi, K., & Luo, S. (2017). Assessment and learning without grades? Motivations and concerns with implementing gradeless learning in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(3), 361–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2015.1114584

Norton, L. S. (2020). (De)Constructing bridges for development and innovation: Intercultural concerns regarding ICT4D. American Behavioral Scientist, 64(13), 1921–1932. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764220952099

Norton, L. S., & Fatigante, M. (2018). Being international students in a large Italian university: Orientation strategies and the construction of social identity in the host context. Rassegna Di Psicologia, 35(3), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.4458/1415-03

Oconnor, J. S., & Lessing, A. D. (2017). What we talk about when we don’t talk about grades. Schools: Studies in Education, 14(2), 303–318. https://doi.org/10.1086/693793

OECD. (2019). OECD data collection programme: Education and training. http://stats.oecd.org/

Passeggia, R., Testa, I., Esposito, G., Picione, R. D. L., Ragozini, G., & Freda, M. F. (2023). Examining the relation between first-year university students’ intention to drop-out and academic engagement: The role of motivation, subjective well-being and retrospective judgements of school experience. Innovative Higher Education, 48(5), 837–859. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-023-09674-5

Pekrun, R., Marsh, H. W., Suessenbach, F., Frenzel, A. C., & Goetz, T. (2023). School grades and students’ emotions: Longitudinal models of within-person reciprocal effects. Learning and Instruction, 83, 101626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2022.101626

Percell, J. C. (2017). Lessons from alternative grading: Essential qualities of teacher feedback, the clearing house: A journal of educational strategies. Issues and Ideas, 90(4), 111–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.2017.1304067

Pippin, T. (2014). Roundtable on pedagogy: Response: Renounce grading? Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 82(2), 348–355. https://doi.org/10.1093/JAAREL/LFU002

Poorthuis, A. M. G., Juvonen, J., Thomaes, S., Denissen, J. J. A., de Castro, B. O., & van Aken, M. A. G. (2015). Do grades shape students’ school engagement? The psychological consequences of report card grades at the beginning of secondary school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(3), 842–854. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000002

Potter, J. (2013). Discursive psychology and discourse analysis. In The Routledge handbook of discourse analysis (pp. 104–119). Routledge.

Pulfrey, C., Buchs, C., & Butera, F. (2011). Why grades engender performance-avoidance goals: The mediating role of autonomous motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103(3), 683–700. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023911

Pulfrey, C., Darnon, C., & Butera, F. (2013). Autonomy and task performance: Explaining the impact of grades on intrinsic motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(1), 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029376

Ragelienė, T. (2016). Links of adolescents identity development and relationship with peers: A systematic literature review. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(2), 97–105.

Rohe, D. E., Barrier, P. A., Clark, M. M., Cook, D. A., Vickers, K. S., & Decker, P. A. (2006). The benefits of pass-fail grading on stress, mood, and group cohesion in medical students. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 81(11), 1443–1448. https://doi.org/10.4065/81.11.1443

Spencer, K. (2017). A new kind of classroom: No grades, no failing, no hurry. New York Times.

Verhoeven, M., Poorthuis, A. M. G., & Volman, M. (2019). The role of school in adolescents’ identity development. A literature review. Educational Psychology Review, 31(1), 35–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-018-9457-3

Whitmell, T. E. T. (2020). Teachers navigating their experiences of “Going Gradeless” in Ontario. Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto.

Yukhymenko-Lescroart, M., & Sharma, G. (2022). Sense of life purpose is related to grades of high school students via academic identity. Heliyon, 8(11), e11494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11494

Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (1999). Putting time in perspecive: A valid, reliable individual-differences metric. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1271–1288. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1271

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the school’s principal for the courage she had in promoting such an important innovation, to the teachers for their engagement in accepting the challenge of changing the way they communicate their evaluation to the students, and to the students for their profound reflections on their learning processes and the role of evaluation in it. It was a privilege for us to assist all of you in this project.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi Roma Tre within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in full compliance with the ethical standards and Italian national regulations on research involving human participants and approved by the ethics committee of “Roma Tre” University of Rome. The data for this study were collected through qualitative methods, i.e., focus group. Due to the confidential nature of the data, and the need to protect the anonymity and privacy of the participants, the raw data cannot be made available for sharing. However, the findings and conclusions of the study are presented in detail in the manuscript, and readers can refer to these for a comprehensive understanding of the research outcomes.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix A

Appendix A

1.1 Questions that guided the Focus Groups

-

1.

How would you describe your experience with competency-based assessment?

-

2.

Two years later, what positive aspects have you identified in this approach? What are the critical aspects?

-

3.

When you receive an assessment, how do you use the teachers’ comments? Can you provide an example?

-

a.

Think about the last test/quiz;

-

b.

Consider the best or worst assessment experience you’ve had and the actions that followed in terms of study, method, effort…

-

a.

-

4.

How would you use the numerical grade? Can you provide an example?

-

a.

In comparison to the experiences mentioned earlier, what would you have done differently?

-

a.

-

5.

Why do you think it is useful—if you believe it is—to accompany competency assessments with a numerical grade?

-

6.

What does the grade represent for you?

-

7.

In your opinion, what would be the ideal assessment?

-

8.

After 2 years, have you had or do you still have difficulties managing this type of feedback among yourselves, with teachers, or perhaps at home with your parents?

-

9.

Would you like to add any comments on aspects we haven’t discussed yet?

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Costa, S., Norton, L.S. & Pirchio, S. Discourses about grades and competency-based evaluation: Exploring communicative and situated meanings at an Italian high school. Soc Psychol Educ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-024-09911-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-024-09911-5