Abstract

This study examined the relationships between first-year university students’ academic motivation, retrospective evaluation of school experiences, subjective well-being, engagement and intention to drop out. Self-determination theory, the SInAPSi model of academic engagement, the hedonic approach, and the retrospective judgment process were used to frame the study. A final sample of 565 first-year Italian students enrolled in Science-Technology-Engineering-Mathematics (STEM) courses (Biology, Biotechnologies, Chemistry, Computer Science, Physics, Mathematics) was included. Three mediation models based on structural equations were tested to analyse the relationships between the proposed variables: motivation as an antecedent of dropout intention with only commitment as a mediator (model 1); model 1 + subjective well-being as a second mediator (model 2); model 2 + retrospective judgement as an antecedent (model 3). The results showed that in all models the more autonomous motivational styles predicted students’ engagement, which in turn directly and indirectly influenced their intention to drop out. In model 2, subjective well-being acted as a mediator of the relationships between motivation, engagement and dropout intentions. In model 3, we found that subjective well-being also fully mediated the relationships between retrospective judgement and engagement. Overall, our findings provide new insights into the mechanisms underlying student engagement and dropout at university and may inform university policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

University drop-out is a widespread issue in European States (European Commission, 2018). The average drop-out rate is 33% for undergraduate students (OECD, 2019). The Italian situation is among the worst in Europe (AlmaLaurea, 2020), with one of the lowest numbers of graduating students (OECD, 2019).

In order to describe the phenomenon of university dropouts, it is necessary to operationalise the concept of dropout (Behr et al., 2020). University dropout is commonly used to refer to leaving university without a degree. In general, the term ‘dropout’ is used as a synonym for other terms such as ‘withdrawal’ and ‘attrition’, although they refer to different aspects of the act of leaving university. While the first two terms describe a student leaving from the student’s perspective, the term ‘attrition’ reflects an institutional perspective. Furthermore, while ‘dropping out’ refers to a more negative and involuntary process, ‘withdrawal’ defines a more voluntary decision to leave university. In positive terms, ‘persistence’ and ‘completion’ refer to the student perspective and ‘retention’ or ‘completion’ to the institutional perspective. In theoretical and empirical research, all these different terms are often used interchangeably. It is also possible to distinguish the dropout phenomenon from students’ motives for leaving university and to identify different degrees of voluntariness (Tinto, 1975). Empirical research analyses many of these determinants of voluntary or involuntary dropout. In summary, current empirical research on student dropout has identified a number of relevant reasons for dropping out of tertiary education. In fact, generally dropout is rarely attributed to a single factor, but rather to an interplay of many factors from different domains contributing to the phenomenon. Among the factors influencing persistence, some are defined ‘hard’ determinants, mostly related to individual aspects of the university experience and therefore outside the control of the university, such as age (Belloc et al., 2010; Müller & Schneider, 2013), gender (Aina, 2013; Ghignoni, 2017) social background (Di Pietro & Cutillo, 2008) and school grades (Sarcletti & Müller, 2011; Stinebrickner & Stinebrickner, 2014); others are the so-called ‘soft’ determinants, factors such as motivation (Heublein et al., 2017), satisfaction (Suhre et al., 2007), integration (Tinto, 1975) or academic fit (Schmitt et al., 2008), factors that can be malleable and positively influenced by the institution (Larsen et al., 2013). There is no consensus in the literature on the order of importance of each of these factors, as dropping out is more likely to be a long decision-making process during which a number of conditions and problems accumulate and lead students to leave university without a degree. While some studies have found that most students decide to drop out already in the first year (Del Bonifro et al., 2020), other authors point out that the dropout phenomenon cannot be considered as a single and limited moment, but as a process that unfolds gradually (Alrashidi et al., 2016).

In order to better understand this process and to provide a mechanism for improving retention rates, in this study we examine the relationships between dropout intention, student engagement, retrospective evaluation of school experience, motivation and subjective well-being at earlier stages of students’ university careers. In the following sections, we first describe the components of our theoretical framework and then justify the hypothesised relationships.

Student Engagement and its Dimensions

Student Engagement (SE), or also Academic Engagement, is currently one of the most important constructs being studied in the context of higher education in relation to its apparent and critical role in student achievement and retention. The growing attention that SE has received has led to the coexistence of different approaches to the nature of this construct (Kahu, 2013). The main critical point in the field of SE research is the lack of distinction between what qualifies as SE process, antecedent and consequence. Furthermore, there is very little consensus on its definition (Christenson et al., 2012). Consensus has been reached on the core idea that the nature of SE goes beyond mere attendance and participation in class and concerns students’ ability to persevere and make sustained efforts to achieve academic goals, to self-regulate behaviour and choices, to negotiate and share goals with others (peers, teachers, families, etc.), to accept the challenge of their limits in learning processes. SE is generally associated with a positive but realistic view of one’s own learning activity, the ability to demonstrate and develop resources in terms of diligence, activity and initiative. Overall, researchers widely share the idea that SE is a complex and multifaceted construct (Fredricks et al., 2004), a contextual and personal concept (Kahu, 2013) and a dynamic process (Lawson & Lawson, 2013). From this perspective, SE could be seen as a catalyst for a positive process that could be included in the ‘soft’ determinants of dropout.

From a psychological perspective, SE can be defined as a set of patterns in students’ motivation, cognition and behaviour (Trowler, 2010).One of the most influential models, by Fredricks et al. (2004), conceptualises engagement as a multidimensional construct consisting of three dimensions: (1) behavioural aspects (e.g. positive classroom behaviour); (2) cognitive processes carried out during study (e.g. use of self-regulated learning strategies); (3) emotional processes (e.g. positive interest).

In this paper, we adopted an innovative model of engagement, the recently validated SInAPSi Academic Engagement model (Freda et al., 2023). The model includes six dimensions of SE: value of the university and sense of belonging, value of the university course, perception of ability to persist in university choice, engagement with university professors, engagement with university peers, relationships between the university and the relational network. The six dimensions can be grouped into three overarching macro dimensions: (1) the value attributed to the academic institution and the academic project (Freda et al., 2016); (2) the perception of the difficulties encountered, which affect the persistence in the academic project (Girelli et al., 2018a, b); (3) the social relationships built in the university context (namely with peers and teachers) (Alivernini et al., 2019; De Picione et al., 2022; Kahu, 2013).

Academic Motivation

Motivation can be defined as the drive for behaviour (Russell et al., 2005). According to Self-Determination Theory (SDT, Deci & Ryan, 1985), motivation is the perception that one is responsible for one’s own actions and behaviour, which are aimed at self-actualisation and autonomy.

In the SDT model, motivation is described by a hierarchical, multidimensional model with five components that correspond to different degrees of autonomy in engaging in a given activity (Vallerand & Ratelle, 2002): Amotivation, which refers to the lack of control over the behaviour performed and the will not to continue the commitment in a given situation; External regulation, which refers to behaviours that are guided by external demands, by the will to obtain a material reward or to avoid criticism and punishment; Introjected regulation, which includes forms of duty or the avoidance of guilt, but also the improvement of self-perception as the main driving force behind a certain behaviour; Identified regulation, which involves a conscious and autonomous perception of the value associated with the behaviour performed, which is perceived as relevant to the achievement of a personal goal; Intrinsic motivation, which involves engaging in an activity for the pleasure and satisfaction inherent in the activity, regardless of the consequences. Previous studies have shown that academic motivation (AM) is positively related to student achievement (Habók et al., 2020) and negatively related to dropout intention (Girelli et al., 2018a). Therefore, we hypothesise that AM is also an antecedent of SE (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000) and include the construct in our model.

Affectivity and Subjective Well-being

In psychological research, several research approaches focused on the construct of well-being (Petrillo et al., 2014). In the hedonic tradition, to which we refer in this study, subjective well-being (SWB) describes individuals’ experiences according to their personal and subjective, positive and negative, evaluations (Diener & Ryan, 2009). It is conceptualized as a two-dimensional construct that describes the individual’s state of psychological well-being (Diener & Emmons, 1984). The dimensions include a positive and a negative affective polarization (Watson et al., 1988). The positive affect measures whether a person feels excited, animated, or passionate about an enacted behaviour. Negative affect measures whether person feels distressed, anxious, or guilty in the enacted behaviour. Previous research suggests that there is a small correlation between SWB and school performance (Bücker et al., 2018), with no moderating effect of age, gender and disciplinary area. However, other studies show that positive affect acts both as a direct antecedent of performance (Fredrickson, 2001) and as a mediators of motivation (Gillet et al., 2013). Other studies have shown that positive emotions influence SE (Oriol-Granado et al., 2017). Thus, we expect that SWB, especially positive affect to act as a mediator of the relationships between motivation and SE and between motivation and drop-out intention.

Retrospective Judgement of School Experience for Academic Attainment

Retrospective judgements can be defined as a personal and unguided reflection on a prior experience and aims at improving self-regulated learning (Eva & Regehr, 2008). When involved in a retrospective judgment, an individual is enacting a conscious and deliberate elaboration of one’s own understanding of the past experience (Mann et al., 2009). For this study, we will consider the students’ retrospective judgement on previous learning experiences and performances (Finn, 2015). We included this construct in our study since research has shown that the behaviour in given situation is informed by the memory of previous affective experiences, especially during the ending (Fredrickson, 2000). Finn (2015) posited that a process of retrospective judgment may also happen during learning experiences that are challenging for students. Hence, our study aims at extending the notion of retrospective judgment to the school-university transition, which prior studies showed to be a very challenging moment for students (Fokkens-Bruinsma et al., 2021). Studies on memory research show that reflecting on successful experiences has an intrinsic value for students and thus has the potential to affect their future decisions and behaviours (Finn & Miele, 2016). Similarly, studies on retrospective judgment of performance (confidence) showed that it has a positive correlation with academic achievement (Stankov et al., 2012) and persistence in learning tasks (Sreenivasulu & Subramaniam, 2014). For such reasons, we expect that students’ retrospective judgment on their past school experience and performance can be a significant precursor of SWB, SE and drop-out intention at first-year of the university programme.

The Present Study

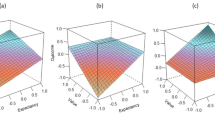

Building on the above theoretical framework, this study will assume that motivational and self-belief constructs, as retrospective judgements of one’s own school experience and performance, can support students’ retention in university courses. Namely, when students have more autonomous style of motivation and positive self-beliefs about what they have learned before and about their previous performances, their drop-out intention decreases. Moreover, building on prior studies, we will also assume that motivation and retrospective judgements affect SWB and SE, which in turn reduce drop-out intention (Fredin et al., 2015). Thus, the main aim of this study is to test the relationships amongst these constructs using a multistage structural equation modelling approach (see methods section). While prior studies have mostly investigated the relationships between motivation, self-related beliefs (e.g., self-efficacy) and academic achievement (Habók et al., 2020; Fokkens-Bruinsma et al., 2021), the proposed models did not include engagement as mediator of such relationships. Conversely, the studies that proposed structural models for academic achievement in which engagement acts as a mediating variable (e.g., Oriol-Granado et al., 2017) do not account for motivational and retrospective judgment as precursors. To provide a more comprehensive account of the above relationships, in the present study, we propose a model that includes five different constructs: motivation, retrospective judgment, SWB, SE, and drop-out intention. The complete proposed model is depicted in Fig. 1. The hypothesized direct effects can be summarized as follows:

-

1)

academic motivation and retrospective judgment have a direct effect on SE and SWB;

-

2)

motivation, retrospective judgment, and SE have a negative direct effect on drop-out intention;

The hypothesized mediated effects can be summarized as follows:

-

1)

SWB, specifically positive activation, mediates the relationships between academic motivation, retrospective judgment and SE;

-

2)

SE mediates the relationships between academic motivation, retrospective judgment and drop-out intention;

-

3)

SE mediates the relationships between SWB and drop-out.

-

4)

Thus, we attempt to answer the following research question:

What direct and indirect relationships can be discovered amongst the investigated constructs of motivation, retrospective judgment, subjective well-being, student engagement, and drop-out intention?

Materials and Methods

Participants

This study involved a convenient sample of 680 students enrolled in the first academic year at the University of Naples Federico II (Italy) in academic year 2018-19. Students were informed about the study and signed a consent form to participate. Overall, 115 students did not sign consent to report, and thus use their IDN, so it was not possible to include them in the study. Therefore, the analysis was carried out with the remaining 565 students. Age distribution was the following: 18–20 (89.7%); 21–23 (8.5%); greater than 23 (0.7%) About 1.1% did not indicate their age. Female students were 52.4% of the sample. All students attended a scientific degree course: biology (35.0%); physics (18.9%); chemistry (16.6%); mathematics (13.5%); informatics (8.1%); biotechnologies (7.8%).

Measures

Student Engagement

The SInAPSi Academic Engagement Scale (SAES; Freda et al., 2023) was used to measure SE. The SAES was developed to address several limitations inherent of the current measurement of the construct in higher education and to evaluate the processes underlying SE in a longitudinal perspective. Specifically, the SAES operationalizes the engagement model for university students discussed above with 29 items (on a 5-point Likert scale) organized into 6 scales, corresponding to each of the six dimensions of the model: (1) university value and sense of belonging (e.g., Attending university is a great opportunity for me); (2) perception of the capability to persist in the university choice (e.g., I’d leave the university right away if I had an alternative (R); (3) value of university course (e.g., I find my studies very significant for my professional plans); (4) engagement with university professors (e.g., My instructors are interested in my opinions and what I say); (5) engagement with university peers (e.g., Studying with other students is useful to me); (6) relationships between university and relational net (e.g., I talk about my professional plans with my family). The SAES has a valid factor structure and shows good convergent, discriminant, construct-related, and criterion-related validity (Freda et al., 2023). For this study, we also used as concurrent measurement of SE the University Student Engagement Inventory (USEI; Marôco et al., 2016) instrument, which was recently validated in Italian (Esposito et al., 2022). The USEI is composed of 15 items on a 5-point Likert scale, organized around the three dimensions of Fredricks and colleagues’ SE conceptualization (cognitive, emotional and behavioural). Example items are: I try to integrate subjects from different disciplines into my general knowledge (cognitive); My class is an interesting place to be (emotional); I pay attention in class (behavioural).

Subjective Well-Being

To measure SWB we used the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Terracciano et al., 2003), which is the most frequently used tool to evaluate positive activation (PA) and negative activation (NA). Generally, PA and NA are dimensions used to describe the affective experience and represent the affective and emotional components of subjective well-being (Diener et al., 1985). In particular, the PA dimension reflects the level of positive commitment, enthusiasm, excitement, activation, and dedication of the individual (e.g., At the university I feel proud). The NA dimension refers to subjective distress, which is recognizable in a wide range of negative affects, such as fear, guilt, shame (e.g., At the university I feel sad). The Italian version showed good psychometric properties. The overall questionnaire is composed of 31 items (on a 5-point Likert scale).

Motivation

The Academic Motivation Scale (AMS; Alivernini & Lucidi, 2008) is one of the most frequently used measures of AM. The scale is composed of 20 items (on a 7-point Likert scale) organized into 5 dimensions, each measuring one of the regulation styles of AM described in the theoretical background. Example items are: I chose this university course because…: …I don’t know why, I had to do something anyway (amotivation); …it is what the others want from me (external regulation); … to prove to myself that I can get the degree (introjected regulation); …. because it will be useful for my future career (identified regulation); …. because the topics are interesting (intrinsic motivation). In the Italian version, the AMS shows a good validity and reliability.

Drop-out Intention

To measure the drop-out intention, we used the dimension of the SAES Perception of the capability to persist in the university choice in its reversed form (Freda et al., 2023). The reason was that the SAES dimension included more items (4) than the usual single-item drop-out scales used in prior studies (Alivernini et al., 2019). To improve validity of drop-out intention measure, we also asked students to indicate how frequently they thought to leave university on a three-level scale (1 = Never; 2 = Sometimes; 3 = Often).

Retrospective Judgment of School Experience

Retrospective judgment score was calculated as the product of the scores obtained in two items (Conf_Item1: “How do you assess the preparation you received at high school for the university course you have chosen?”, and Conf_Item2: “How do you assess your achievement at high school in relation to the university course you have chosen?”) on a 5-point Likert Scale and then normalized in the [0–1] interval. We calculated the variable product to better discriminate students with low scores in one of the items.

Procedure

Data collection took place in the classrooms at the end of the second semester of the participants’ first academic year (2018-19). The instruments were administered in paper form by local operators of the University of Naples Federico II. Students completed all the instruments in about 30–45 min. The participants signed an informed consent in accordance with the ethical principles of the Italian Association of Psychology. Students not willing to participate were allowed to leave the room. All the data were collected in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) and the Italian Law on Privacy and Data Protection 196/2003.

Data Analysis

The hypothesized model was then tested following a multi-stage approach (Hayes & Usami, 2020), which first estimates factor scores obtained from the measurement model using a Maximum Likelihood Estimation, and then uses these scores for the subsequent path analysis to estimate the regression paths of the structural model. The reason for using the multi-stage approach is that it enhances the stability of the solution avoiding the effects of misspecifications that always happen in complex models with multiple predictors, mediators and dependent variables, as in our case. In other words, the piecewise estimation of the structural parameters is aimed to avoid that the effects of the measurement model misspecification extend to the structural parameter estimates. Morevoer, since we let the factors in the measurement model be correlated, and given also the size of our sample, the bias resulting from using factor scores can be considered acceptable for our analysis (Lu et al., 2011). Hence, we first performed a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of the SAES, AMS, and PANAS instruments. Several indices were used to assess the quality of the CFA models: c2 /df, normed fit index (NFI), incremental fit index (IFI), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Values of c2/df less than 3, NFI, IFI, CFI, and TLI above 0.90, SRMR and RMSEA less than 0.05 are indicative of good fit (Kline, 2015). Criterion validity of the SAES was again established for our sample by calculating the correlation between the SAES and the USEI factor score. The validity of the scale was established by correlating the total score with the categorial variable indicating how frequently the student thought to leave the university course through a t-test after collapsing the “sometimes” and “often” levels. Before testing the full model in Fig. 1, we first analysed two simpler models: Model 1, with only motivation construct as precursor and SE as mediator; and Model 2, which includes SWB as additional mediator. Significance of direct and indirect effects was tested through a bootstrap procedure to determine bias-corrected confidence intervals for the estimated regression paths. If the confidence interval does not include the zero, the path is statistically significant. Both CFAs and path analysis were carried out using IBM AMOS v. 26.

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analyses

Student Engagement

We first tested a 5-factor structure of the SAES instrument, after excluding the subscale of the Perception of the capability to persist in the university choice, using it to measure the drop-out intention. The 5-factor model fitted well the data (c2 /df = 2.699, p < 0.001, NFI = 0.909, IFI = 0.940, CFI = 0.940, TLI = 0.929, SRMR = 0.0578, RMSEA = 0.055). Then, we also performed a second-order CFA of the SAES instrument for the following reasons: (a) prior SE measures showed also a second-order factor structure; (b) reducing collinearity between constructs to improve the meaningfulness of structural relationships. The second-order model also shows a good fit: c2/df = 2.691, p < 0.001, NFI = 0.907; IFI = 0.893; CFI = 0.939; TLI = 0.930; SRMR = 0.0598; RMSEA = 0.055. We hence tested whether the second-order factor solution was significantly different from the 5-factor model and the c2 statistics showed non statistically significant differences at p = 0.05 (c2 = 8.656; df = 4, p = 0.07). Finally, after performing a second-order CFA of the USEI instrument (c2/df = 3.409, p < 0.001, NFI = 0.934; IFI = 0.952; CFI = 0.952; TLI = 0.935; SRMR = 0.0460; RMSEA = 0.055), we found that the obtained correlation between the SAES and USEI single-factor scores was significant at p < 0.01 level (Pearson’s r = 0.576, BC CI = 0.457–0.682). We, therefore, decided to use the factorial scores of the 1-factor SAES instrument for subsequent analysis.

Subjective Well-Being

The two-factor model, which features the PA and NA dimensions, fitted well the data: c2/df = 2.733, p < 0.001, NFI = 0.854; IFI = 0. 902; CFI = 0.901; TLI = 0.889; SRMR = 0.0645; RMSEA = 0.055. The correlation between the PA and AN was low (r = -0.035), and the two scales could be considered as independent. Hence, given also that many NA items were designed as the negative formulation of PA items, in order to better clarify the structural model, we chose to keep in the subsequent analysis only the PA dimension.

Academic Motivation

Concerning the AM, the model fitted well the data: c2/df = 3.044, p < 0.001, NFI = 0.932; IFI = 0. 954; CFI = 0.953; TLI = 0.943; SRMR = 0.0698; RMSEA = 0.060. When inspecting the factorial scores, we noted the scores of the dimensions amotivation and external regulation were highly skewed and could possibly affect the subsequent structural analysis. Hence, we kept for the subsequent analysis only the factorial scores of the dimensions introjected regulation, identified regulations and intrinsic motivation. Moreover, although the questionnaire allows to obtain also 2 global indexes (Relative Activation Index and Relative Activation Index Latent), the opportunity of using a single score for the motivation scale is debated since there is not clear evidence in support of the existence of a motivation continuum (Hopkins et al., 2021). Therefore, in the subsequent analyses, we used the factor scores of the three types of regulation separately.

Drop-out Intention

Average value was 1.72 ± 0.03 (st. err.). The t-test shows that students who often or sometimes think to leave university (Nleave = 190) have significantly higher scores in the drop-out intention scale with respect to students who seldom or never think to leave university (Nremain = 441): Mleave = 1.90; Mremain = 1.67; t = − 3.326, d.o.f. = 166.478, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = − 0.338, CI = [–0.538; – 0.138].

Retrospective Judgment of School Experience and Performance

Average value of normalized retrospective judgment score was 0.62 ± 0.22 (st.dev.). Kurtosis and asymmetry values are acceptable: kur = − 0.26 ± 0.20; asymm. = − 0.27 ± 0.10.

The statistics for the variables included in the model are reported in Table 1.

Hypothesized Models Testing

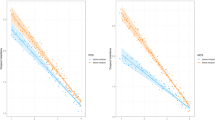

The significant direct paths are reported in Figs. 2, 3 and 4, while direct, indirect and total effects for the three models are summarized in Tables 2, 3 and 4. Model 1, 2 and 3 explain 20%, 22% and 22% of the drop-out intention, respectively. Regarding the regression paths, in Model 1, intrinsic and identified regulations have a positive significant effect on engagement, which in turn has a negative direct effect on drop-out intention. Intrinsic and introjected regulations have also a positive and negative direct effect on drop-out intention, respectively. Model 2 shows the same significant paths of Model 1. Furthermore, we found a significant positive effect of intrinsic motivation on SWB, which in turn has also a significant positive effect on engagement and drop-out intention. The full Model 3 adds to Model 2 the retrospective judgment of school experience, which has significant effects on SWB, drop-out intention, while the effect on engagement is not significant.

The mediation paths for the three models are reported in Table 5. In Model 1 intrinsic and identified regulations have an indirect effect on drop-out intention, with engagement as mediator. In Model 2, other than the indirect effects of Model 1, we also found that engagement partially mediates the relationships between identified regulation, SWB and drop-out intention, while SWB partially mediates the relationships between intrinsic regulation and engagement and drop-out intention. In the full Model 3, we found three further indirect effects: retrospective judgment on engagement, fully mediated by SWB; retrospective judgment on drop-out intention, partially mediated by SWB.

Discussion

This study tested the direct and indirect relationship between motivation, retrospective judgment, SBW, SE, and intention to drop out. To overcome the limitation inherent a scarce focus on the combined effect of SE and SWB on drop-out intention (Gillet et al., 2013; Guo, 2018), we tested three models of increasing complexity in which the mediating effects of SE and SWB are first tested separately and then combined in the final model, using three styles of motivational regulation as precursors and drop-out intention as outcome variables, using multi-stage structural equation modeling. We found that the full model, with motivation and retrospective judgment as precursors, and SWB and SE as mediators, has better fit and explains more variance of the outcome variable.

Direct Relationships

Regarding the direct effects, our results show that in all tested models, as expected, intrinsic motivation has a direct negative effect on intention to drop-out. In contrast, introjected motivation, related to the improvement of self-perception, is positively associated to drop-out intention. Thus, if students are extrinsically motivated in their academic choice, they will more likely choose to drop-out when encountering difficulties or obstacles, accordingly to prior works suggesting that students who are intrinsically motivated have better performances than students with extrinsically motivated behaviors (Guo, 2018). Concerning the direct effects of motivation on SWB and SE, the path analysis for all models suggests that students who are motivated either intrinsically or extrinsically because of the perceived utility value in the university (introjected regulation) get more engaged during their academic life, but that only intrinsic motivation significantly predicts SWB. This result expands prior research (Guo, 2018) and may be explained by considering that our conceptualization of SE includes as relevant dimension the utility value of the chosen university course. Second, we note that both SWB and SE significantly predict drop-out intention. Therefore, positive emotions and engagement decrease the likelihood of drop-out when encountering difficulties. Third, in the final model, we found a direct effect of retrospective judgment on SWB, but we could not detect a significant relationship between retrospective judgment and engagement. From this result, we can infer that, in our sample, the SWB is mostly affected by their perception of being able to perform well in the university exams while, at the same time, the same perception may lead the students to reduce their efforts in building an engaging relationship with the university context.

Indirect Relationships

Concerning mediating effects, most of the hypothesized relationships were confirmed. First, as hypothesized from previous findings (Gillet et al., 2013), we found that positive activation of SWB mediates the effect of intrinsic motivation and retrospective judgment on both engagement and drop-out intention, suggesting that positive emotions may be affected by motivation and perception of prior preparation to deal with university exams. Specifically, the perception of being well prepared for the university course and being intrinsically motivated may activate positive affects in the relationship with the academic context. In turn, in line with prior work in a variety of educational fields (Uludag, 2016), the more students feel positive emotions when attending university courses, the more they are engaged and feel able to persist in their academic choice. An interesting result is that SWB fully mediates the relationships between perceived retrospective judgment and engagement. A possible interpretation is that the perception of preparation primarily affects SWB, which activates engagement processes and only indirectly helps students who already perceive themselves as prepared for the university to acknowledge the utility value of university and of the relationships with peers and instructors, which are relevant dimensions in our conceptualization of engagement. Second, in all models, SE mediates the relationships between identified and intrinsic motivation with drop-out intention. However, in contrast to our hypothesis, in Model 3, engagement does not mediate the relationships between retrospective judgment and intention to drop-out. The role of engagement as mediator of intrinsic and identified motivation confirms prior studies (Hsieh, 2014) and can be interpreted by considering that, at the university level, students’ participation into university life may be more likely driven by their own interests and the perception of the utility of the attended courses for their future career (Rayner & Papakonstantinou, 2020). Therefore, students more easily realize that attending university courses is a means to achieve their future goals (Habók et al., 2020). The absence of the mediating effect of engagement in the retrospective judgment – drop-out intention relationship may be likely due to the weak relationships between retrospective judgment and engagement, which we have discussed above. However, since other studies found a mediating effect of engagement in the relationships between prior preparation and academic achievement (Ribeiro et al., 2019), more research is required. Third, we found, as hypothesized, that SE partially mediates the relationships between SWB and drop-out intention and academic achievement. This result confirms the positive mutual relationships between SWB and SE (Guo, 2018) and can be explained by considering that SWB likely activates psychological and relational aspects underlying engagement, which have a direct effect on the will to persist in the university choice.

Limitations and Future Directions

The main limitation of this study is that the variables were only measured once. A longitudinal study is currently underway in which we are measuring the actual dropout, engagement, well-being and motivation of the same sample in the third year of their university course. We did not include the performance variable in our model because the students involved had already taken some exams in the first semester. The role of previous academic performance on engagement is currently being investigated. A related limitation is that we administered the survey in paper and pencil format. Therefore, our sample may be biased towards more motivated and engaged students who are more likely to attend university classes. A third limitation is that our sample consists mainly of science students. Different results might be obtained if students from different university courses and from different countries were included. Finally, we did not include socio-economic background in the model due to a lack of administrative data on family income. We acknowledge this and the others discussed above as limitations for the generalisability of our results and for the limited percentage of variance explained by the models considered. Although the confirmation of previously hypothesised relationships could suggest their generalisability, given the contextual nature of academic engagement and also the lack of a cross-cultural comparison in our study, we could only suggest that in future studies an attempt be made to replicate these results, also taking into account cultural differences. In this respect, a replication study is needed.

Implications and Conclusions

This study aimed to show the role of affective variables such as academic motivation, retrospective judgement, SE and SWB on students’ intention to persist in their university choice and academic performance. The full model supports that academic motivation and perceived adequacy of school preparation for university are significant antecedents of intention to persist in university choice, while SWB and SE act as mediating variables. From this perspective, this study confirmed relationships already highlighted in previous work with different samples from different disciplines and different cultural backgrounds, namely the mediating role of academic engagement between motivation and dropout intention. Nevertheless, this study also proposed innovative relationships, such as the introduction of SWB in the model. Future research should focus also on several other constructs relevant for academic achievement and persistence, such as productive persistence (Yeager et al., 2013), academic fit (Schmitt et al., 2008) and growth mindset (Dweck, 2006), that showed to be significantly considerable in a perspective of academic engagement promotion (Edwards & Beattie, 2016; Zhao et al., 2021). Therefore, in a practical perspective, the development of interventions should take into consideration the interplay between the academic engagement and other variables in relation to the university drop out.

This study has several practical implications for higher education policy. First, it is worth paying early attention to students’ motivation to attend university. Thus, increasing intrinsic motivation (i.e., interest) and identified motivation (i.e., utility) may increase students’ levels of SWB and SE, which in turn will increase their chances of persisting in their choice and performing better in university examinations. Furthermore, in line with previous evidence in science education (Kaiser et al., 2020), our study strongly recommends improving students’ self-assessment programmes to provide them with evidence that it is worth investing time and effort during secondary school because it has a significant impact on their future university career (Mahlberg, 2015). One possible way to do this is through continuous feedback from teachers to stimulate not only students’ self-regulation, but also more autonomous forms of motivation (Chen & Huang, 2016). Our study also suggests that early assessment of SE can be an effective tool to identify critical aspects of university life, such as peer and teacher relationships, that can be strengthened to increase students’ chances of persisting in their choices. Overall, our study suggests that more attention should also be paid to affective and metacognitive variables in order to more effectively increase performance and correspondingly reduce dropout rates over a given period of time. In addition, our findings suggest the importance of promoting university interventions to foster students’ identification with the institution, active participation and relational competencies.

Data Availability

The data reported in this manuscript have been presented only in this study.

Code Availability

Dataset will be made available under request.

References

Aina, C. (2013). Parental background and university dropout in Italy. Higher Education, 65(4), 437–456. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-012-9554-z.

Alivernini, F., & Lucidi, F. (2008). The academic motivation scale (AMS): Factorial structure, invariance and validity in the italian context. Testing Psychometrics Methodology in Applied Psychology, 15(4), 211–220. https://doi.org/10.4473/TPM.15.4.3.

Alivernini, F., Cavicchiolo, E., Girelli, L., Lucidi, F., Biasi, V., Leone, L., Cozzolino, M., & Manganelli, S. (2019). Relationships between sociocultural factors (gender, immigrant and socioeconomic background), peer relatedness and positive affect in adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 76(August), 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.08.011.

AlmaLaurea, C. I. (2020). XXII indagine-profilo dei laureati 2019 [XXII investigation-profile of 2019 graduates]. Retrieved from https://www.almalaurea.it/i-dati/le-nostre-indagini/profilo-dei-laureati.

Alrashidi, O., Phan, H. P., & Ngu, B. H. (2016). Academic engagement: An overview of its definitions, dimensions, and major conceptualisations. International Education Studies, 9(12), 41–52. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v9n12p41.

Behr, A., Giese, M., Kamdjou, T., H. D., & Theune, K. (2020). Dropping out of university: A literature review. Review of Education, 8(2), 614–652. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3202.

Belloc, F., Maruotti, A., & Petrella, L. (2010). University drop-out: An italian experience. Higher Education, 60(2), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9290-1.

Bücker, S., Nuraydin, S., Simonsmeier, B., Schneider, M., & Luhmann, M. (2018). Subjective well-being and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 74, 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2018.02.007.

Chen, Y., & Huang, S. J. (2016). The relationship between teacher autonomous support and high school students’ self-motivation and basic psychological needs. Journal of Southwest China Normal University (Natural Science Edition), 41(10), 141–145. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00374.

Christenson, S. L., Reschly, A. L., & Wylie, C. (Eds.). (2012). Handbook of research on student engagement. Springer Science & Business Media.

De Luca Picione, R., Testa, A., & Freda, M. F. (2022). The sensemaking process of academic inclusion experience: A semiotic research based upon the innovative narrative methodology of “upside-down-world”. Human Arenas, 5, 122–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42087-020-00128-4.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Conceptualizations of intrinsic motivation and self-determination. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior (pp. 11–40). Springer.

Del Bonifro, F., Gabbrielli, M., Lisanti, G., & Zingaro, S. P. (2020). Student dropout prediction. Artificial Intelligence in Education: 21st International Conference AIED 2020 Ifrane Morocco July 6–10 2020 Proceedings Part I, 12163, 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52237-7_11.

Di Pietro, G., & Cutillo, A. (2008). Degree flexibility and university drop-out: The italian experience. Economics of Education Review, 27(5), 546–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2007.06.002.

Diener, E., & Emmons, R. A. (1984). The independence of positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(5), 1105–1117. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.47.5.1105.

Diener, E., & Ryan, K. (2009). Subjective well-being: A general overview. South African Journal of Psychology, 39(4), 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/008124630903900402.

Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The New psychology of success. Random House.

Edwards, A. R., & Beattie, R. L. (2016). Promoting Student Learning and Productive Persistence in Developmental Mathematics: Research Frameworks informing the Carnegie Pathways. NADE Digest, 9(1), 30–39. EJ1097458.

Esposito, G., Marôco, J., Passeggia, R., Pepicelli, G., & Freda, M. F. (2022). The italian validation of the university student engagement inventory. European Journal of Higher Education, 12(1), 35–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2021.1875018.

European Commission, E., Eurydice (2018). The european Higher Education Area in 2018: Bologna process implementation report. Publications Office of the European Union.

Eva, K. W., & Regehr, G. (2008). I’ll never play professional football” and other fallacies of self-assessment. Journal of Continuing Education in Health Profession, 28(1), 14–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.150.

Finn, B. (2015). Retrospective utility of educational experiences: Converging research from education and judgment and decision-making. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 4(4), 374–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2015.06.001.

Finn, B., & Miele, D. B. (2016). Hitting a high note on math tests: Remembered success influences test preferences. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning Memory and Cognition, 42(1), 17–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0000150.

Fokkens-Bruinsma, M., Vermue, C., Deinum, J. F., & van Rooij, E. (2021). First-year academic achievement: The role of academic self-efficacy, self-regulated learning and beyond classroom engagement. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 46(7), 1115–1126. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1845606.

Freda, M. F., Gonzàlez-Monteagudo, J., & Esposito, G. (2016). Working with underachieving students in higher education: fostering inclusion through narration and reflexivity. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315659121.

Freda, M. F., Raffaele, D. L. P., Esposito, G., Ragozini, G., & Testa, I. (2023). A new measure for the assessment of the university engagement: The SInAPSi academic engagement scale (SAES). Current Psychology, 42, 9674–9690. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02189-2.

Fredin, A., Fuchsteiner, P., & Portz, K. (2015). Working toward more engaged and successful accounting students: A balanced scorecard approach. American Journal of Business Education, 8(1), 49–62. https://doi.org/10.19030/ajbe.v8i1.9016.

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2000). Extracting meaning from past affective experiences: The importance of peaks, ends, and specific emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 14(4), 577–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999300402808.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56, 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.218.

Ghignoni, E. (2017). Family background and university dropouts during the crisis: The case of Italy. Higher Education, 73(1), 127–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0004-1.

Gillet, N., Vallerand, R. J., Lafrenière, M. A. K., & Bureau, J. S. (2013). The mediating role of positive and negative affect in the situational motivation-performance relationship. Motivation and Emotion, 37(3), 465–479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-012-9314-5.

Girelli, L., Alivernini, A., Salvatore, S., Cozzolino, S., Sibilio, M., & Lucidi, F. (2018a). Coping with the first exams: Motivation, autonomy support and perceived control predict the performance of first year university students. Journal of Educational Cultural and Psychological Studies, 18, 165–185. https://doi.org/10.7358/ecps-2018-018-gire.

Girelli, L., Alivernini, A., Lucidi, F., Cozzolino, S., Savarese, G., Sibilio, M., & Salvatore, S. (2018b). Autonomy supportive contexts, autonomous motivation, and self-efficacy predict academic adjustment of first-year university students. Frontiers in Education, 3(95), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2018.00095.

Guo, Y. (2018). The influence of academic autonomous motivation on learning engagement and life satisfaction in adolescents: The mediating role of basic psychological needs satisfaction. Journal of Education and Learning, 7(4), 254–261. https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v7n4p254.

Habók, A., Magyar, A., Németh, M. B., & Csapó, B. (2020). Motivation and self-related beliefs as predictors of academic achievement in reading and mathematics: Structural equation models of longitudinal data. International Journal of Educational Research, 103, 101634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101634.

Hayes, T., & Usami, S. (2020). Factor score regression in connected measurement models containing cross-loadings. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 27(6), 942–951. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2020.1729160.

Heublein, U., Ebert, J., Hutzsch, C., Isleib, S., König, R., Richter, J., & Woisch, A. (2017). Zwischen studienerwartungen und studienwirklichkeit. Forum Hochschule, 1/2017.

Hopkins, E. G., Lyndon, M. P., Henning, M. A., & Medvedev, O. N. (2021). Applying rasch analysis to evaluate and enhance the academic motivation scale. Australian Journal of Psychology, 73(3), 348–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530.2021.1904794.

Hsieh, T. L. (2014). Motivation matters? The relationship among different types of learning motivation, engagement behaviors and learning outcomes of undergraduate students in Taiwan. Higher Education, 68(3), 417–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9720-6.

Kahu, E. R. (2013). Framing student engagement in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 38(5), 758–773. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.598505.

Kaiser, L. M., Großmann, N., & Wilde, M. (2020). The relationship between students’ motivation and their perceived amount of basic psychological need satisfaction – a differentiated investigation of students’ quality of motivation regarding biology. International Journal of Science Education, 42(17), 2801–2818. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2020.1836690.

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford publications.

Larsen, M. S., Kornbeck, K. P., Kristensen, R., Larsen, M. R., & Sommersel, H. B. (2013). Dropout phenomena at universities: what is dropout? why does dropout occur? what can be done by the universities to prevent or reduce it? Technical report, Danish Clearinghouse for Educational Research.

Lawson, M. A., & Lawson, H. A. (2013). New conceptual frameworks for student engagement research, policy, and practice. Review of Educational Research, (83)3, 432–479. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313480891.

Lu, I., Kwan, E., Thomas, R., & Cedzynski, M. (2011). Two new methods for estimating structural equation models: An illustration and a comparison with two established methods. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 28, 258–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2011.03.006.

Mahlberg, J. (2015). Formative self-assessment college classes improve self-regulation and retention in first/second year community college students. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 39(8), 772–783. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2014.922134.

Mann, K., Gordon, J., & MacLeod, A. (2009). Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: A systematic review. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 14, 595–621. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2016.1164686.

Marôco, J., Marôco, A. L., Campos, J. A. D. B., & Fredricks, J. A. (2016). University student’s engagement: Development of the university student engagement inventory (USEI). Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 29(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-016-0042-8.

Müller, S., & Schneider, T. (2013). Educational pathways and dropout from higher education in Germany. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies, 4(3), 218–241. https://doi.org/10.14301/llcs.v4i3.251.

OECD (2019). OECD data collection programme: Education and training. http://stats.oecd.org/.

Oriol-Granado, X., Mendoza-Lira, M., Covarrubias-Apablaza, C. G., & Molina-López, V. M. (2017). Positive emotions, autonomy support and academic performance of university students: the mediating role of academic engagement and self-efficacy. Revista de Psicodidáctica (English Ed.), 22(1), 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1387/revpsicodidact.14280.

Petrillo, G., Caso, D., & Capone, V. (2014). Un’applicazione del mental health continuum di Keyes al contesto italiano: Benessere e malessere in giovani, adulti e anziani [An application of Keyes’s mental health continuum in the italian context: Well-being and malaise in youngs, adults and elderlies]. Psicologia della salute: quadrimestrale di psicologia e scienze della salute, 2, 159–181.

Rayner, G., & Papakonstantinou, T. (2020). The use of selfdetermination theory to investigate career aspiration, choice of major and academic achievement of tertiary science students. International Journal of Science Education, 42(10), 1635–1652. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2020.1774092.

Ribeiro, L., Rosário, P., Núñez, J. C., Gaeta, M., & Fuentes, S. (2019). First-year students background and academic achievement: The mediating role of student engagement. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2669. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02669.

Russell, V. J., Ainley, M., & Frydenberg, E. (2005). Student motivation and engagement. Schooling Issues Digest, 2, 1–11.

Sarcletti, A., & Müller, S. (2011). Zum stand der studienabbruchforschung. Theoretische perspektiven, zentrale ergebnisse und methodische anforderungen an künftige studien. Zeitschrift für Bildungsforschung, 1(3), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s35834-011-0020-2.

Schmitt, N., Oswald, F. L., Friede, A., Imus, A., & Merritt, S. (2008). Perceived fit with an academic environment: Attitudinal and behavioral outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 72(3), 317–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2007.10.007.

Sreenivasulu, B., & Subramaniam, R. (2014). Exploring undergraduates’ understanding of transition metals chemistry with the use of cognitive and confidence measures. Research in Science Education, 44(6), 801–828. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-014-9400-7.

Stankov, L., Lee, J., Luo, W., & Hogan, D. J. (2012). Confidence: A better predictor of academic achievement than self-efficacy, self-concept and anxiety? Learning and Individual Differences, 22(6), 747–758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2012.05.013.

Stinebrickner, R., & Stinebrickner, T. (2014). Academic performance and college dropout: Using longitudinal expectations data to estimate a learning model. Journal of Labor Economics, 32(3), 601–644. https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/121970.

Suhre, C. J., Jasen, E. P., & Harskamp, E. G. (2007). Impact of degree program satisfaction on the persistence of college students. Higher Education, 54(2), 207–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-005-2376-5.

Terracciano, A., McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. Jr. (2003). Factorial and construct validity of the italian positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS). European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 19(2), 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1027//1015-5759.19.2.131.

Tinto, V. (1975). Dropout from higher education: A theoretical synthesis of recent research. Review of Educational Research, 45(1), 89–125.

Trowler, V. (2010). Student engagement literature review. The Higher Education Academy, 11(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9202-4.

Uludag, O. (2016). The mediating role of positive affectivity on testing the relationship of engagement to academic achievement: An empirical investigation of tourism students. Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism, 16(3), 163–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/15313220.2015.1123130.

Vallerand, R. J., & Ratelle, C. F. (2002). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: A hierarchical model. In E. L. Deci, & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 37–63). University of Rochester Press.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063.

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy-value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1006/CEPS.1999.1015.

Yeager, D., Bryk, A., Muhich, J., Hausman, H., & Morales, L. (2013). Practical measurement (p. 78712). Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Zhao, H., Xiong, J., Zhang, Z., & Qi, C. (2021). Growth mindset and college students’ learning engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic: A serial mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 621094. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.621094.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This study was funded by the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research, under the national project “Piano Nazionale Lauree Scientifiche” (PLS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RP, IT, GE, and MFF designed the study and managed the literature search. RP, IT and GR undertook the analysis. RP, IT and GE wrote the first draft of the manuscript and contributed to the subsequent redrafting of the manuscript. RP, IT, GE, RDP, GR and MFF critically reviewed the draft of the manuscript and contributed to the interpretation of results. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest/Competing Interests

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Ethics Approval

At the beginning of the study, approval for conducting this study was obtained from the coordinators of the involved degree courses at the University of Naples Federico II (Italy). The work complied with relevant ethical standards for human subjects’ protections.

Consent to Participate

Students were informed about the study and had to sign a consent form to participate to the study and agree to report their own course ID, which was used to match data obtained from the administration offices. Those who wished not to participate to the study were allowed to leave the room.

Consent for Publication

We are aware that, if accepted for publication, a certification of authorship form will be required that all co-authors will sign.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Passeggia, R., Testa, I., Esposito, G. et al. Examining the Relation Between First-year University Students’ Intention to Drop-out and Academic Engagement: The Role of Motivation, Subjective Well-being and Retrospective Judgements of School Experience. Innov High Educ 48, 837–859 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-023-09674-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-023-09674-5